Abstract

This paper uses the published results of successive Iranian censuses (1966–2011) and the 2 % micro-data from the 2011 census to examine the trends and patterns of solo living in Iran. The results show a recent rise in solo living in both rural and urban areas. Furthermore, a convergence in the prevalence of solo living is observed in both areas since the mid-1980s, which has removed their initial differences by the end of the period of study. Solo living is most prevalent among the elderly and to a lesser extent among young men. The fact that the age composition of sole persons has been relatively stable over time but their gender composition has been transformed to a female-dominant pattern provides evidence for both continuity and change in solo living in Iran. The results of multivariate analyses suggest that there are gender norms about living arrangements in Iran, which vary by age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

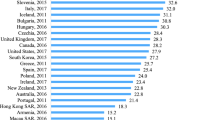

Several studies have noted an increase in solo living in the United States of America and European countries (Belcher 1967; Keilman 1988; Chandler et al. 2004; Fokkema and Liefbroer 2008; Demey et al. 2011). As Keilman (1988: 314) noted, “by the 1980s, in all Scandinavian countries, in all countries in Western Europe except one, and in some Eastern European countries at least every fifth hhFootnote 1 is headed by a solitary”. According to the most recent United Nations statistics, all five countries with the highest share of solo living (i.e. Finland, Norway, Switzerland, Austria and Estonia) are located in Europe. In these countries, more than one-third of households are comprised of only one member (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division 2013; Table 4).

The rise in solo living in many parts of the world has invoked comprehensive studies about different aspects of this emerging type of living arrangement (e.g. Klinenberg 2012; Jamieson and Simpson 2013). Yet no study, to date, has investigated solo living in Iran. Living alone can influence patterns of social interaction, intergenerational relationships and consumption of resources, and thus warrants careful attention in family research. Studying different aspects of solo living is particularly interesting in the context of Iran where long-existing pro-family values and norms (see Ladier-Fouladi 2002; Abbasi-Shavazi and McDonald 2008; Aghajanian 2013) have traditionally provided the elderly and disadvantaged members with emotional, social and economic family support. This would, in turn, leave few people living alone.

However, Iran has undergone several structural as well as family changes. Urbanization, expansion of education and improvement in health and longevity are examples of such structural changes. More specifically, the proportion of urban population increased from 39 % of the population in 1966 to 71 % in 2011; during the same period, the proportion of literate population increased from only 29 % (males 40 % and females 18 %) to 85 % (males 88 % and females 81 %); and the life expectancy at birth increased from 63 years (males 61 years and females 66 years) in 1990 to 74 years (males 72 years and females 76 years) in 2012 (Statistical Centre of Iran 2013a; World Bank 2014).

Later marriage, fewer children, and more divorce are examples of changes in family life. Between 1986 and 2011, the singulate mean age at marriage (SMAM) of men and women increased, respectively, from 23.2 and 19.7 years to 26.7 and 23.4 years (Torabi and Askari-Nodoushan 2012). During the same period, the total fertility rate (TFR) declined from 6.2 to only 1.8 children per woman (Abbasi-Shavazi et al. 2009; Abbasi-Shavazi et al. 2013). Finally, the number of divorces per 1000 marriages increased from <100 in the 1980s and 1990s to 154 by 2011 (Aghajanian 2013). Nevertheless, some aspects of family life have persisted in Iran. For instance, consanguineous marriage has remained relatively constant over the past five decades and childbearing is still practised within marriage (Givens and Hirshman 1994; Abbasi-Shavazi and Torabi 2007; Abbasi-Shavazi and McDonald 2008).

This raises the question as to whether solo living provides evidence for continuity or change in family life in Iran. It can be argued that the recent development of the social welfare system (see Ladier-Fouladi 2002) in addition to other structural changes such as the expansion of education, urban dwelling, and wage employment will undermine the supporting function of families and improve chances of alternative living arrangements such as living alone. However, the social acceptability of alternative living arrangements can modify these structural influences. For instance, in a historically patriarchal society, such as Iran, there should be more flexibility towards male than female solo living especially at younger ages, leaving young women with restricted living arrangement options. Thus, interplay of social and economic factors is expected to determine the final outcome.

This paper aims to take a step in filling the existing literature gap about solo living in Iran. Utilizing the published results of successive Iranian censuses (1966–2011) and the 2 % micro-data from the 2011 census, the paper examines the trends in and patterns of solo living in Iran. First, the prevalence of solo living over the past five decades is examined; then, the social, economic and demographic characteristics of persons who live alone are described and the extent to which living alone is related to these characteristics is determined. These findings not only improve our understanding about living arrangement dynamics, but also provide further evidence about continuity and change in family life in Iran. Notable changes in the prevalence and patterns of solo living can be regarded as another example of change, whereas continuity may exemplify the persistence of family values in Iran.

Review of the literature

Goode (1963) argued that as societies become more urbanized and industrialized, the size and complexity of households are reduced and nuclear or conjugal households, containing parents and their children, predominate. In fact, the trend towards smaller households has been observed in many parts of the world (e.g., Keilman 1988; Ayad, Barrer and Otto 1997; Bongaarts 2001; Fokkema and Liefbroer 2008).

Another explanation for long-scale changes in demographic behaviors is offered by the concept of the “Second Demographic Transition”, which relates these changes to the spread of the ideology of self-development (Lesthaeghe 1995; Van de Kaa 2001). As Keilman (1988: 302) pointed out, “[t]he trend toward a more independent, individual life style may be interpreted as indicating that people are more prepared than they were in the past to pay the price of loneliness in return for privacy and greater independence.”

Although the emerging tendencies towards nuclear households and more independent life styles makes solo living more acceptable and possible, several social, economic and demographic factors have also been identified as influencing its propensity. The existing literature finds that age, gender, marital status, educational attainment, labour force participation, housing availability, and living standards are important factors related to living alone.

Belcher (1967: 539) identified age and marital status as “two variables which seem to be most directly related to the incidence of people living alone.” His findings indicate that the incidence of living alone in the USA increases with age and this type of living arrangement is more common among widowed or never-married individuals. Fokkema and Liefbroer (2008) also found that living alone is concentrated at older ages in Europe.

Gender differences in living alone have also been investigated and confirmed by several studies (e.g. Keilman 1988; Fokkema and Liefbroer 2008; Demey et al. 2011). Fokkema and Liefbroer (2008) showed that younger men and older women are more likely to live alone in Europe. They attributed this pattern to gender differences in other demographic behaviors. More specifically, women’s higher life expectancy and earlier marriage result in more chances of living alone at older ages among women. However, men are more likely to practise solo living at younger ages because they marry later than women. Demey et al. (2011, 2013) found a higher increase in solo living in mid-life in the UK among men, and argued that although marriage dissolution is the major pathway into living alone, especially for women in their late mid-life, a substantial group of mid-life never-married men also practise solo living in the UK.

In addition to the aforementioned demographic factors (i.e. age, gender and marital status), some socio-economic factors are also related to living alone. Stone et al. (2011) argued that participation in higher education and labour market, housing prices and international migration can potentially influence the living arrangements of young adults. They also emphasized the complexity of these influences based on financial resources and ethnic background, leading to choices between different living arrangements such as living alone, with parents, with non-relatives or with a partner.

The role of economic conditions should not be underestimated. While increased living standards and housing availability can accelerate solo living (see Keilman 1988; Wall 1989), economic recession, employment insecurity, increased housing prices and limited financial resources can encourage individuals to share households with family or non-family housemates and hinder either union formation or solo living (see Stone et al. 2011). Wolf and Soldo (1988) showed that income and disability, which constrain living arrangement preferences, are important determinants of household composition for older women in the USA. Evidence from the UK also suggests that solo living at older ages is associated with higher economic resources and good health, but at younger ages and in mid-life, unemployment and lower socio-economic status are characteristics of those living alone (Hall et al. 1997; Stone et al. 2011; Demey et al. 2013).

The existing literature proposes that a combination of tendencies towards autonomy, privacy and an individual life style alongside socio-economic and demographic factors influence solo living. For instance, in the context of Iran, marriage postponement can increase living alone especially among young men; more incidence of divorce can lead to living alone, especially among young and middle-aged men; and increased longevity can raise solo living particularly among women. The outcome is expected to be determined by a set of social and economic factors (e.g. labour force participation, job security, housing availability, social acceptability of alternative living arrangements), which may facilitate or hinder living arrangement choices. This paper examines the trends in and patterns of solo living in Iran to provide greater insights into living alone in this country.

Data and method of analysis

The data are derived from two main sources: the published results of successive Iranian censuses (1966, 1976, 1986, 1996, 2006 and 2011) and the 2 % micro-data from the 2011 census. Solo living is identified as households with only one member, also known as one-person households. It is important to note that two types of household are identified in the Iranian censuses: ordinary and group households. According to the Statistical Centre of Iran (2013a), the ordinary households contain one or more persons who live together and make common provision for food and other essentials of living, whereas the group households are a group of people who live together because of a common characteristic (e.g. barracks and dormitories). Here, we focus on the former, which by definition include persons who live alone and according to the 2011 census micro-data comprise 99.6 % of Iranian households.Footnote 2

In order to identify the patterns of living alone, gender, age, marital status, education, and labour force participation of sole persons are examined. The published census results only provide information about the gender and age of sole persons. Thus, the remaining variables (i.e. marital status, education, and labour force participation) are drawn from the 2011 census micro-data. This only allows us to determine changes in the gender and age composition of sole persons over time. The other variables are compared between those living alone (i.e. sole persons) and those not living alone (i.e. non-sole persons). This will provide a better understanding about differentials between the two groups in one particular year (i.e. 2011). Finally, in order to examine the relative importance of different correlates of solo living, a series of logistic regression models are applied to the 2011 census micro-data. In order to understand how these influences differ between men and women and at different life-course stages, the logistic regression models are estimated by the gender and age of respondents. The age groups represent the young (15–29 years), mid-life (30–64 years), and old (65 years or higher) stages.

Findings

Trends in solo living

Figure 1 shows the trend in living alone at the national and rural–urban levels during the past five decades. At the national level, households headed by a sole person comprised around 5.5 % of households until the mid-1970s. The figure declined to around 4.5 % in the following two decades (1980s and 1990s), before a rise to 5.2 % in 2006 and then to 7.2 % in 2011. Thus, in only 5 years (2006–2011) the share of solo households rose by nearly 40 %, increasing their number from 903,000 in 2006 to 1,512,000 in 2011.

Percentage of one-person households at the national and rural–urban levels, Iran, 1966–2011. Source: data adapted from Statistical Centre of Iran (2013a)

The prevalence of solo living varied considerably between rural and urban areas until the mid-1980s, became more similar between 1986 and 2006 and converged by 2011. More specifically, one-person households comprised 6.6 % of urban households in 1966. The figure declined to 4.3 % by 1996, before a rise to 5.2 and 7.2 % in 2006 and 2011, respectively. In rural areas, one-person households comprised 4–5 % of households for three decades (1966–1996). The figure rose to 5.3 % in 2006 and to 7.1 % in 2011.

It is worth noting that a similar trend and pattern is observed when focusing on the share of sole persons (i.e. the ratio of the number of sole persons to the number of household members instead of the number of households). More specifically, the proportion of sole persons was 1.1 % until the mid-1970s. The figure declined to 1.0 % in the following two decades (1980s and 1990s), before a rise to 1.3 % in 2006 and then to 2.0 % in 2011. Furthermore, the rural–urban differences are comparable with those observed in Fig. 1.

Gender composition

As shown in Table 1, the gender composition of sole persons has changed considerably over time. In 1966, men comprised 56.2 % and women 43.8 % of sole persons in Iran. The share of women steadily rose and reached more than two-thirds of sole persons by 2011. This pattern can be related to increased longevity, particularly among women, leading to a rise in the number of sole widowed women at older ages. Other factors such as women’s higher educational attainment and more social flexibility towards female solo living may have contributed to this trend. The same pattern (i.e. a reduction in the share of male sole persons) is observed in both urban and rural areas.

Age composition

Figure 2 depicts the age composition of sole persons in the whole country, as well as in urban and rural areas, between 1986 and 2011.Footnote 3 Three points are obvious from the upper panel of Fig. 2, which includes both men and women. First, although solo living in the whole country is concentrated at old ages (50.9 % of sole persons are aged 65 or more), but it is also relatively common at young ages (i.e. 20–29 years). Second, at younger ages, there is a slight reduction in solo living among those aged less than 24 years and an increase at older ages during the period of study. This trend is consistent with the marriage postponement of Iranian men and women, as mentioned in the introduction. Third, at older ages, there is a reduction in solo living in the late mid-life (ages 55–64) and an increase at older ages over time. This trend is consistent with the increased longevity in Iran over the past few decades, which shifts solo living due to widowhood to higher ages.

Age composition of sole persons by gender at the national and rural–urban levels, Iran, 1986–2011. Note: at each age, the number of sole persons is divided by the total number of sole persons and multiplied by 100. Source: Data adapted from Statistical Centre of Iran (2013a)

These trends and patterns are observed in both urban and rural areas, although solo living at younger ages is more common in urban areas, whereas living alone at older ages is more prevalent in rural areas. In 2011, the proportion of sole persons aged 20–34 years was 1.5 times larger in urban (17.2 %) than in rural (11.3 %) areas. Moreover, the proportion of sole persons aged 65 years or higher was 1.2 times larger in rural (59.1 %) than in urban (47.8 %) areas. This phenomenon can partly be explained by the migration of young people from rural to urban areas (see Mahmoudian and Ghassemi-Ardahaee 2014), leading to an increase in the share of sole youth in urban and elderly in rural areas. Another explanation could be more acceptance of solo living among young adults in urban than in rural areas where stronger pro-family values and norms are expected to prevail.

The middle panel of Fig. 2 shows the age distribution of male sole persons. There is a notable rise in solo living among men at ages 20–29 years, followed by a fall before another rise at ages 65 years or higher. Again, this pattern is observed both in urban and rural areas, although solo living at younger ages is more common in urban areas, whereas living alone at older ages is more prevalent in rural areas. It seems that male solo living in Iran is related to widowhood and to the never-married status.

Female solo living (shown in the lower panel of Fig. 2) follows a different age distribution as it slightly increases before the age of 50, but a sharper rise is observed afterwards. In 2011, 83.8 % of sole women in the whole county were aged 50 years or more; the share of those aged 50–54, 55–59, 60–64 and 65 years or more is, respectively, 5.2, 7.5, 9.6 and 61.5 %. The same pattern is observed in both urban and rural areas, although in rural areas the proportion of sole women is higher at older ages. Thus, women’s solo living seems to be concentrated at older ages and related to their widowhood.

Marital status

As shown in Table 2, marital status considerably varies between sole and non-sole persons and between men and women.Footnote 4 Considering both men and women, widowhood is the most prevalent marital status among sole persons (62.3 %), followed by being never married (19.0 %), married (9.9 %) and divorced (8.8 %). Among those who do not live alone, the majority is married (68.6 %), around one-third are never married, 3.1 % are widowed, and less than 1 % is divorced. This pattern can be related to the younger age structure of non-sole persons; the median ages of sole and non-sole persons are 65 and 33 years, respectively.

The place of residence does not have a notable influence on marital status of either group. However, considerable gender differences in marital status are observed among both groups. The high share of widowhood is magnified among sole women, with 78.3 % of them being widowed and only 5.8 % being married. This is consistent with our previous finding, showing the concentration of sole women at old ages. Among sole men, widowhood becomes less significant, whereas other forms of marital status, especially being never married, become more pronounced. It is also interesting to note that nearly one in five sole men is married. This may reflect the temporary absence of a sizeable proportion of husbands, because of work, education or other reasons, although a comprehensive explanation of this phenomenon is beyond the scope of this study.

Educational attainment

As shown in Table 3, educational attainment varies not only by type of living arrangement (living alone or not alone), but also by gender and place of residence. Taking both men and women into account, over half of sole persons are illiterate, whereas only one in four has high school or university education. A similar pattern exists in urban areas, but in rural areas the proportion of illiterates is much higher (78.2 vs. 46.1 %) and the attainment of high school or university education is much lower (7.0 vs. 30.5 %) than in urban areas. Non-sole persons are better educated than those living alone, regardless of the area in which they live. Overall, only 15.6 % of them are illiterate, while 48.6 % have high school or university education. Again, higher education of those who are not living alone is in line with their younger age structure and the process of educational expansion in the country.

There is also a considerable difference in the educational attainment of men and women, particularly among those living alone. Overall, sole men are better educated than sole women. At the national level, 29.7 % of the former, compared to 66.0 % of the latter are illiterate. On the other hand, 44.1 % of sole men compared to 15.2 % of sole women have high school or university degrees. Again, this difference may be partly related to the younger age structure of sole men (median age of 44 years) than sole women (median age of 69 years). These gender differences also exist in urban and rural areas, although urban dwellers generally display a higher educational attainment than those living in rural areas. Gender differences in education are less pronounced among none-sole persons, partly because of similarity of the age structures of non-sole men and women (median age of 33 and 32 years, respectively).

Labour force participation

As shown in Table 4, labour force participation varies by living arrangement, gender and place of residence. Considering both men and women, having income with no job (32.0 %) and being employed (28.8 %) are the two most common statuses among sole persons. Employed sole persons are more frequent in rural than in urban areas (36.1 vs. 26.1 %), while the reverse is true for sole persons who have income with no job (34.3 % in urban and 25.7 % in rural areas). A different pattern is observed among those who do not live alone because nearly one-third of them are employed and another third consists of those engaged in home duties, hereafter ‘housekeepers’, in both urban and rural areas.

As with other findings of this paper, substantial gender differences exist in labour force participation patterns, which can be related to differences in the age and educational attainment of sole men and women and the structure of the labour market. Overall, more sole men than women participate in the labour market (i.e. are employed or in search or employment) or are recorded as students. However, more women than men have incomes with no job or are housekeepers. The same pattern prevails in both urban and rural areas. Among those who do not live alone, men are still more likely to participate in the labour market and women are still more likely to be housekeepers but in contrast to those living alone, having an income with no job is more common among men than women. It is also worth noting that the proportion of employed sole women in rural areas is nearly two times larger than in urban areas (26.3 vs. 12.7 %) but a reverse pattern is observed among those not living alone (9.5 % in urban and 5.2 % in rural areas). This finding can suggest that sole rural women are in more financial need than those living in urban areas.

Multivariate analysis

This section presents the results of logistic regression analysis of the impact of different correlates of living alone. Table 5 presents the results for men and women combined, whereas Tables 6 and 7 contain the results for men and women, respectively. In all tables, column 1 shows the estimated unadjusted odds ratios that enable us to determine the impact of each covariate, without taking the effect of other covariates into account. Column 2 shows the adjusted odds ratio, estimated from a full model including all the covariates. Columns 3, 4, and 5 contain the results for young, middle-aged, and old persons, respectively.

According to column 1 of Table 5, living in urban areas, being female, being unmarried, belonging to older age groups and having income with no job all increase the odds of living alone. Women are 2.2 times more likely than men to live alone. Moreover, the odds of living alone among middle-aged and old persons are, respectively, 2.6 and 29.4 times larger than among young persons. The odds of solo living among widowed, divorced, and never-married persons are, respectively, 140.7, 65.2, and 4.8 times larger than among married persons. All other factors reduce the odds of solo living. More specifically, there is a reduction in the odds of solo living by an increase in the level of education up to the university education. Moreover, unemployed persons, students and housekeepers are all less likely than employed persons to live alone. The same patterns is observed among men and women, except that there is no evidence to suggest that the rural or urban place of residence is related to the odds of solo living among women (see column 1 of Tables 6, 7).

Column 2 of Table 5 shows that after accounting for the effect of different factors, living in urban areas, being unmarried, belonging to older age groups, and having income with no job still increase the odds of solo living. Nevertheless, several changes are observed. First, women become less likely than men to practise solo living. Second, among different categories of marital status, the highest odds of living alone are observed among divorced (rather than widowed) persons. Third, there is no evidence to suggest that obtaining university education is related to solo living. The same pattern is observed among men and women, except that university education is related to solo living among women (see column 2 of Tables 6, 7).

Columns 3–5 of Table 5 show the adjusted odds ratio for young, middle-aged and old persons. Both at the young and mid-life ages, living in urban areas, being unmarried and having income with no job increase the odds of living alone. On the other hand, higher education (up to university education) and different sorts of unemployment (except for having income with no job) reduce the odds of solo living. Being unmarried increases the odds of solo living at all ages. More specifically, solo living is most strongly related to being divorced, followed by being widowed and being never-married. Unlike the young and middle-aged persons, old women are more likely than old men to live solo. Moreover, it is only among old persons that after adjusting for other influences, those with university education are more likely than illiterates to practise solo living. There is no evidence to suggest that other educational levels have an influence on solo living at old ages. Unlike in other age groups, all sorts of unemployment (even having income with no job) reduce the odds of solo living, but place of residence is not related to solo living at old ages.

These influences vary considerably between men and women (see Tables 6, 7). Women mostly display similar patterns to those observed for the whole sample. The main difference is that the rural or urban place of residence is not related to solo living among young women. Among men, however, a quite different pattern is observed. Here, there is no evidence to suggest that the place of residence is related to solo living among either middle-aged or old men. Being unmarried still increases the odds of solo living, but the extent to which each category is related to solo living varies among different age groups. Among young men, solo living is most strongly related to being widowed, followed by being divorced and being never-married. Among middle-aged men, being divorced appears more important than being widowed but being never-married is still less important (in terms of the magnitude of the relationship). Among old men, being divorced still displays the highest value, but being never-married becomes more important than being widowed.

It is important to note that the variables included in the analysis are able to explain 43.2 % of the variation in solo living in the whole sample (29.9 % among men and 49.5 % among women) (see the final row of each Tables 5, 6, 7). Moreover, moving from young to mid-life and to old ages generally increases the strength of the fitted models.

Summary and conclusion

This paper used different sources of data to study the trends in and patterns of solo living in Iran, which are, in turn, summarized and discussed in this section. An examination of the prevalence of solo living during the past five decades at the national level showed a recent rise in the share of persons who live alone, which appeared after a reduction in the mid-1980s. This is quite consistent with trends in marriage, fertility and divorce in Iran, which have been partly attributed to the pro-family atmosphere that resulted from the Islamic Revolution in 1979 and hampered by the spread of individualistic and materialistic preferences since the late 1980s (see Abbasi-Shavazi et al. 2002; Aghajanian 2013; Torabi et al. 2013).

Considering the prevalence of solo living in rural and urban areas, the findings suggest a convergence since the mid-1980s. The lower prevalence of solo living in rural areas until the mid-1980s can be related to the existence of stronger family ties and interdependence in rural areas, which increases the protective function of family and leaves few members without family. However, solo living in rural areas has resembled that in urban areas since the mid-1980s, in line with the convergence in the timing of marriage and the number of children in rural and urban areas of Iran (see Abbasi-Shavazi et al. 2009; Torabi and Askari-Nodoushan 2012). This convergence can partly be explained by a diminishing gap between rural and urban areas in terms of different socio-economic attributes (e.g. access to education, health, and means of communication) during the past few decades (see Abbasi-Shavazi et al. 2002). In addition, the rise in the share of sole youth in urban areas and sole elderly in rural areas can partly be related to the flow of migrants, moving from rural to urban areas to continue education or to search for better job opportunities (see Mahmoudian and Ghassemi-Ardahaee 2014). This phenomenon may have been exacerbated by increased longevity, resulting in spending more years in widowhood, particularly among women in rural areas.

An examination of the patterns of solo living showed that it is mostly prevalent among the elderly and to a lesser extent among young men. As far as the individual’s intention is concerned, these patterns can fall into two categories of voluntary and involuntary. For example, at young ages people may decide to live alone to experience an independent life style or to pursue better educational or job opportunities in other places. On the other hand, solo living at old ages is mainly related to the death of spouse or due to divorce earlier in life. In such circumstances, solo living is imposed on individuals. This is not to say that each pattern (i.e. young vs. old solo living) is restricted to one element (i.e. voluntary vs. involuntary). Some young people may be exposed to involuntary solo living; e.g. those whose parents move to other places on occupational grounds. Similarly, some widowed elderly may choose to live with their children or other relatives. The data used in this study does not include any information on individuals’ intentions about their living arrangements. Further research is needed to ascertain the degree to which solo living is undertaken voluntarily or involuntary.

Furthermore, sole persons were found to be quite heterogeneous in terms of various socio-economic and demographic attributes, suggesting the multiplicity of routes to solo living in Iran. However, urban residency, being female, being unmarried, getting older, and having access to better economic resources were found to increase the odds of solo living. Interestingly, after adjusting for different socio-economic and demographic attributes, women became less likely than men to live alone. Thus, the initial differences are related to differences of men and women in their characteristics. Also, there is no evidence to suggest that higher education accelerates solo living in Iran, even among young adults, which is contrary to the findings of previous research (see Stone et al. 2011) and merits further investigation.

The results of separate multivariate analyses by the gender and age of respondents suggest that there are gender norms about living arrangements in Iran, which vary by age. For instance, adjusting for different socio-economic and demographic attributes led to lower odds of solo living for women at young and mid-life ages but higher odds of solo living among old women. It seems that younger women are not as motivated or approved as their male counterparts to live alone but the social flexibility towards solo living increases as women become old. Consider the role of marital status as another example. Among both men and women, solo living is most strongly related to divorce, followed by widowhood and being never-married. This pattern is consistent across all age groups for women but not for men. In fact, only the middle-aged men were found to follow this order.

An examination of patterns of solo living provides evidence for both continuity and change in the Iranian family. The relative stability of the age composition of sole persons and the fact that the prevalence of solo living remained quite constant for a long time support the notion of continuity. However, living alone is increasingly prevalent among women, especially at old ages. Although this is in line with increased longevity and the resulting longer period of widowhood and solo living among women, it also implies a tendency towards more privacy and autonomy, which has probably been combined with more social flexibility towards female solo living. Although a deep examination of alternative explanations for such changes is beyond the scope of this article, these are certainly examples of change in the Iranian family, which has been known for its solidarity.

The information presented in this paper has important policy implications because the types of living arrangement can influence patterns of social interaction, intergenerational relationships, and consumption of resources. More research is needed to improve our understanding about the contribution of a wider range of individual (e.g. health condition and ethnic background) and contextual factors (e.g. housing availability and price as well as the overall economic conditions) shaping solo living. It is also important to identify the implications of this type of living arrangement for men and women at different life-course stages.

The future trends of solo living in Iran depend on several factors. An increase in the share of the elderly in the following decades due to the rapid fertility decline and increased longevity will probably lead to a higher share of sole persons. The population aged 65 years or higher comprised 5.6 % of the population of Iran in 2011 (Statistical Centre of Iran 2013a) but this proportion will increase to 10.0 % by 2030, according to the UN medium-variant projections (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2013). Continued delay in marriage and increase in divorce can also lead to more solo living in the future, especially in urban areas. The trajectory is also expected to depend on economic conditions, differences in male and female life expectancy, the occurrence and timing of remarriage for men and women and, of course, the desire for independent life styles and the flexibility of social norms towards alternative living arrangements.

Notes

Household.

In the 1996 census there is no distinction between ordinary and group households, so the results for this year relate to both types of household.

The reason for not including the information for previous years is the lack of information for the whole or part of the age range.

Here and in the rest of the paper, household members aged 15 years or higher are included in the analysis because the share of those aged less than 15 years considerably varies between sole and non-sole households (0.1 vs. 22.7 %, respectively). The minimal proportion of sole persons aged <15 years could indicate reporting errors either in the age or in the living arrangement status; thus, it cannot be regarded as a living arrangement option for very young people in Iran.

References

Abbasi-Shavazi, M. J., & McDonald, P. (2008). Family change in Iran: Religion, revolution, and the state. In R. Jayakody, A. Thornton, & W. Axinn (Eds.), International family change: Ideational perspectives (pp. 177–198). New York: Lowrenec Erlbaum Association.

Abbasi-Shavazi, M. J., McDonald, P., & Hosseini-Chavoshi, M. (2009). The fertility transition in Iran: Revolution and reproduction. Dordrecht: Springer.

Abbasi-Shavazi, M. J., Mehryar, A. H., Jones, G. W., & McDonald, P. (2002). Population, war and modernization: Population policy and fertility changes in Iran. Journal of Population Research, 19(1), 25–46.

Abbasi-Shavazi, M. J., Hosseini-Chavoshi, M., Banihashemi, F., & Khosravi, A. (2013). Assessment of the own-children estimates of fertility applied to the 2011 Iran census and the 2010 Iran-MIDHS. In Paper presented at the XXVII IUSSP International Population Conference, Busan, Korea (pp. 26–31). August.

Abbasi-Shavazi, M. J., & Torabi, F. (2007). Level, trend, and pattern of consanguineous marriage in Iran [Persian]. Journal of Population Association of Iran, 1(2), 61–88.

Aghajanian, A. (2013). Recent divorce trends in Iran. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 54(2), 112–125.

Ayad, M., Barrer, B., & Otto, J. (1997). Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of households. Demographic and Health Surveys Comparative Studies. No. 26. Calverton: Macro International Inc.

Belcher, J. C. (1967). The one-person household: A consequence of the isolated nuclear family? Journal of Marriage and Family, 29(3), 534–540.

Bongaarts, J. (2001). Household size and composition in the developing world in the 1990s. Population Studies, 55(3), 263–279.

Chandler, J., Williams, M., Maconachie, M., Colett, T., & Dodgeon, B. (2004). Living alone: Its place in household formation and change. Sociological Research Online 9(3). http://www.socresonline.org.uk/9/3/chandler.html.

Demey, D., Berrington, A., Evandrou, M., & Falkingham, J. (2011). The changing demography of mid-life, from 1980s to the 2000s. Population Trends, 145, 1–19.

Demey, D., Berrington, A., Evandrou, M., & Falkingham, J. (2013). Pathways into living alone in mid-life: Diversity and policy implications. Advances in Life Course Research, 18, 161–174.

Fokkema, T., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2008). Trends in living arrangements in Europe: Convergence or divergence? Demographic Research, 19, 1315–1418.

Givens, B. P., & Hirshman, C. (1994). Modernization and consanguineous marriage in Iran. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 820–834.

Goode, W. J. (1963). World revolution and family patterns. London: Free Press of Glencoe.

Hall, R., Ogden, P. E., & Hill, C. (1997). The patterns and structure of one-person households in England and Wales and France. International Journal of Population Geography, 3, 161–181.

Jamieson, L., & Simpson, R. (2013). Living alone: Globalization, identity and belonging. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Keilman, N. (1988). Recent trends in family and household composition in Europe. European Journal of Population, 3(3/4), 297–325.

Klinenberg, E. (2012). Going solo: The extraordinary rise and surprising appeal of living alone. New York: The Penguin Press.

Ladier-Fouladi, M. (2002). Iranian families between demographic change and the birth of the welfare. Population (English Edition), 57(2), 361–370.

Lesthaeghe, R. (1995). The second demographic transition in western countries: An interpretation. In K. O. Mason & A. M. Jensen (Eds.), Gender and family change in industrialized countries (pp. 17–62). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mahmoudian, H., & Ghassemi-Ardahaee, A. (2014). Internal migration and urbanization in I.R. Iran. Tehran: University of Tehran and the United Nations Population Fund.

Statistical Centre of Iran (2013a). The results of the 1966–2011 population and housing censuses. Iran: Statistical Centre of Iran. http://www.amar.org.ir.

Statistical Centre of Iran. (2013b). The 2 % sample results of the 2011 population and housing censuses. Iran: Statistical Centre of Iran. http://www.amar.org.ir.

Stone, J., Berrington, A., & Falkingham, J. (2011). The changing determinants of UK young adults’ living arrangements. Demographic Research, 25, 629–666.

Torabi, F., & Askari-Nodoushan, A. (2012). Dynamic in population age structure and changes in marriage in Iran [Persian]. Journal of Population Association of Iran, 7(13), 2–28.

Torabi, F., Baschieri, A., Clarke, L., & Abbasi-Shavazi, M. J. (2013). Marriage postponement in Iran: Accounting for socio-economic and cultural change in time and space. Population, Space and Place, 19(3), 258–274.

United Nations (2013). Demographic yearbook: Tabulations on households’ characteristics. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division. http://unstats.un.org.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2013). World population prospects: The 2012 revision. New York: United Nations.

Van de Kaa, D. J. (2001). Postmodern fertility preferences: From changing value orientations to new behavior. In R. A. Bulatao & J. B. Casterline (Eds.), Global fertility transition (pp. 209–331). New York: Population Council.

Wall, R. (1989). Leaving home and living alone: An historical perspective. Population Studies, 43(4), 369–389.

Wolf, D. A., & Soldo, B. J. (1988). Household composition choices of older unmarried women. Demography, 25(3), 387–403.

World Bank (2014). World bank health indicators. Washington, DC.: World Bank. http://www.data.worldbank.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Professor Wei-Jun Jean Yeung and Dr. Adam Ka-Lok Cheung for their valuable comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Torabi, F., Abbasi-Shavazi, M.J. & Askari-Nodoushan, A. Trends in and patterns of solo living in Iran: an exploratory analysis. J Pop Research 32, 243–261 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-015-9152-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-015-9152-x