Abstract

Background

Although cardiovascular disease (CVD) does not occur until mid to late life for most adults, the presence of risk factors, such as high blood pressure (BP) and cholesterol, has increased dramatically in young adults.

Purpose

The present study examined the relationships between gender and coping strategies, lifestyle behaviors, and cardiovascular risks.

Method

The sample consisted of 297 (71% female) university students. Participants completed a survey to assess demographics, lifestyle behaviors, and coping strategies, and a physiological assessment including lipid and blood pressure (BP) measurements. Data collection occurred from January 2007 to May 2008.

Results

Analyses revealed that age, ethnicity, greater body mass index (BMI), greater use of social support, and less frequent exercise were associated with higher cholesterol, while gender, age, greater BMI, and less frequent exercise were associated with higher systolic BP. There were two significant interactions: one between gender and avoidant coping and the other between gender and exercise on systolic BP, such that for men greater use of avoidant coping or exercise was associated with lower systolic BP.

Conclusion

Understanding how young adults manage their demands and cope with stress sets the stage for understanding the developmental process of CVD. Both coping strategies and lifestyle behaviors must be considered in appraising gender-related cardiovascular risk at an early age before the disease process has begun.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Approximately one-third of adults in the USA have some form of CVD [1]. Although CVD does not occur until mid to late life for most adults, the presence of risk factors, such as high blood pressure (BP) and cholesterol, has increased dramatically in young adults. In the USA over 13% of men and 6% of women ages 20–39 years have high BP, while approximately 9.6% of adolescents 12 to 19 years of age have total cholesterol levels above 200 mg/dL [1]. Gender has been shown to have differential effects on cardiovascular health. The age-adjusted ratio of male to female deaths due to CVDs is 1.5 in the USA [2]; however, the incidence of heart disease, hypertension, and stroke is similar for men and women [3].

Lifestyle behaviors that have been shown to increase risk of chronic illnesses, such as CVD, include smoking tobacco, excess use of alcoholic substances, eating a diet high in triglycerides and fat, and physical inactivity [1, 4]. A recent study found that without the risk factors of high BP, smoking, and elevated cholesterol, 64% of deaths among women and 45% of deaths among men could have been avoided [5]. Gender differences in lifestyle behaviors are already present among high school students surveyed in the USA [6]. In 2007 only 44% of male and 26% of female students report engaging in recommended levels of physical activity per week. Further, males were more likely to be classified as obese (16%) than females (10%). Current cigarette use was slightly higher among male (21%) than female (19%) high school students. Episodic heavy drinking (five or more drinks within a couple of hours) was reported more frequently in males (28%) than in females (24% [6]).

In addition to lifestyle behaviors, stress is a psychosocial factor that plays a prominent role in cardiovascular health [4]. Inability to manage stressful events is associated with heightened sympathetic arousal, which leads to cortisol release [7]. Increased cortisol release has been linked to the CVD process, as well as to other psychological conditions (e.g., depression) associated with increased risk of CVD [7, 8]. The transactional model of stress suggests that an individual and his/her environment are in a dynamic, bidirectional relationship [9]. Within this model, primary appraisal determines whether an event is viewed as stressful, and secondary appraisal determines what coping strategies might be employed. Coping involves cognitive and behavioral strategies used to manage demands perceived as taxing [9]. Learning to cope adequately may serve to lessen the negative impact of stress on the cardiovascular system.

Men and women have been shown to differ in their physiological and psychological responses to stress [10, 11]. Physiologically, many of the differences have been attributed to the protective elements of estrogen, with pre-menopausal women and women taking estrogen-replacement therapy demonstrating lower autonomic activity than men of a similar age [10]. Psychologically, women tend to report greater frequency of stress than men [3] and different coping strategies than men. For example, women endorse greater use of emotion-focused coping, while men report greater use of avoidance [12].

Of the coping strategies and resources that are widely studied, social support appears to have the strongest relationship with CVD and cardiovascular risk factors [13]. Women consistently report greater use of social support than men, including quantity and quality of support received [14, 15]. Preliminary evidence suggests that social support affects cardiovascular functioning through psychophysiological processes [13]. Specifically, there is evidence that greater social support is associated with lower BP, less atherosclerosis, lower cortisol levels, increased oxytocin, and greater immune function [13]. Social interactions also influence the cardiovascular system through behavioral processes such as smoking, eating, and physical inactivity [13].

Gender differences in physiological, lifestyle, and psychological variables associated with CVD may explain why discrepancies in incidence of certain types of CVD have been found between men and women [11, 16]. Identifying the contribution of traditional lifestyle factors such as substance use and exercise, as well as how individuals cope with stress is important in understanding the developmental process of CVD. Such an understanding is necessary for developing interventions that best target change for each gender.

The aim of this study is to examine the relationships among lifestyle behaviors, coping strategies, and cardiovascular risks as measured by elevated BP and cholesterol in a non-medical sample of young adults. The present study attempts to replicate and extend what is known about lifestyle behaviors in college students by examining how lifestyle behaviors and coping strategies relate to cardiovascular risks for each gender. Based on the previously cited research, we expect men to report greater use of tobacco and alcohol, as well as greater physical activity and a higher BMI, as compared to women. Additionally, we expect that, as compared to men, women will report greater use of social supportive and positive/problem-focused coping and lower use of avoidant coping. We also expect lifestyle and coping strategies to differentially relate to cardiovascular measures for each gender.

Method

Participants

Participants (71% female, 29% male) were recruited from psychology classes at a large southwestern university. The average age of the sample was 21.39 years (SD 4.78; range 18–55 years, with 78% between ages 18 and 22 years). Participants were diverse, with 58% European American, 19% African American, 12% Latino/a, and 11% “Other” ethnicity. Students received class credit for participating in a study of “Psychological Predictors of Cardiovascular Health.” Participant eligibility included 1) enrollment in an undergraduate course, 2) 18 years of age or older, and 3) fluency in written and spoken English. Additionally, participants were excluded from physiological assessment if they were pregnant, diabetic, hypoglycemic, or suffered from any condition for which fasting was contraindicated. This included participants taking medications for hypertension or hyperlipidemia.

The sample consisted of 297 participants for psychological and physiological measures. Due to missing data on demographic, lifestyle, and physiological variables, the final sample consisted of 252 participants for cholesterol (n = 45, 15% missing) and 287 participants for SBP (n = 10, 3% missing). Independent samples t-tests and chi-square analyses were used to compare participants with missing data to those for whom data was complete. Participants who did not have SBP readings reported greater days exercised per week (t = 2.32, p < 0.05). There were no significant differences between missing and non-missing participants on gender, age, ethnicity, BMI, cigarette use, alcohol use, coping strategies, or daily hassles.

Procedure

The study was approved by the institutional review board and adhered to all requirements on the use of human subjects. The study consisted of two sessions, and participants were given written informed consent prior to each session. The initial session took place in small groups (3–6 people) in which participants completed a battery of questionnaires. Participants returned for a second session typically within a week to 10 days at which a resting BP assessment and lipid profile were obtained. Prior to their individual appointment for this session, participants were contacted in advance and reminded to fast overnight (no food or drink (except water)) in the 12 hours before the appointment [5]. In addition, they were asked to avoid alcohol or over-the-counter medications or herbal remedies during the fasting period, to refrain from smoking for at least 2 hours before the appointment, and to avoid exercise at least 30 min prior to the appointment. Participants were excluded from analyses if they did not report compliance.

Psychological Measurements

Background Information

Participants completed a brief background information survey that provided demographic information and lifestyle behaviours. Basic information such as age, gender, and academic status was included. Specific questions assessing lifestyle behaviors included, “How many times a week do you use alcohol,” “How many times a day do you smoke,” “How many days per week do you exercise,” “What is your height,” and “What is your weight?” Participants were asked to write the frequency for each item. Self-reported weight and height were used to calculate BMI, which has been shown to provide reliable estimates as compared to measured weight and height in young adults [17].

Coping

The Brief COPE [18] is a 28-item self-report questionnaire modified from the original COPE [19]. The Brief COPE examined 14 coping strategies, including active coping, planning, positive reframing, acceptance, humor, religion, using emotional support, using instrumental support, self-distraction, denial, venting, behavioral disengagement, substance use, and self-blame. Each subscale consists of two items with responses ranging from 1 (I haven’t been doing this at all) to 4 (I’ve been doing this a lot). Sample items included, “I’ve been taking action to try to make the situation better” and “I’ve been giving up trying to deal with it.” Cronbach’s alpha for each subscale is adequate ranging from 0.50 (venting) to 0.90 (substance use). Validity for the Brief COPE has been demonstrated by examination of the intercorrelations among scales on both the Brief COPE and the original COPE measures [18, 19].

To reduce the number of analyses, we conducted a principle components analysis (PCA) of the 28 items of the Brief COPE. A factor loading of 0.31 or higher was present for each item. The first cluster, labeled positive/problem-focused coping, was comprised of the active coping, positive reframing, planning, acceptance, humor, and religion subscales (internal consistency of α = 0.80). The second cluster, avoidant coping, was made up of the self-blame, behavioral disengagement, denial, substance use, self-distraction subscales, and one item from venting (α = 0.77). The third cluster, labeled social supportive coping, consisted of the emotional support and instrumental support subscales, and one item from venting (α = 0.85). A mean score for each component was used for analyses.

Stress

The Hassles portion of The Combined Hassles and Uplifts Scale [20] was used as a measure of perceived stress. Fifty-three items were used to examine an individual’s interactions with the environment that are appraised as stressful in terms of frequency and intensity of each item. Responses range from 0 (None/not applicable) to 3 (A great deal). A sum score was used to determine intensity of perceived stress overall. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.92 within our sample.

Physiological Measurements

Blood Pressure

BP was obtained by taking consecutive readings from the left arm while the participant was seated. After the participant had rested for 5 min, two BP readings were obtained at 2-min intervals. If the difference between the two readings was equal to or less than 5 mm Hg, then the mean of the two readings was used. If the difference between the two readings was greater than 5 mm Hg apart, a third measure was taken and a mean of the three scores was used.

Lipid Profile

Lipid samples were analyzed using the CardioChek PA System, Lipid Panel (http://cardiochek.com/home). If participants followed fasting instructions, they were allowed to participate in the fasting cholesterol screenings. If participants had not fasted or followed directions, cholesterol samples were not collected.

The lipid profile consisted of measures of total cholesterol, HDL, triglycerides, calculated LDL, and a TC/HDL risk ratio. Calculated LDL is a variable that takes into consideration the protective elements of HDL given the total cholesterol, as well as triglycerides. Calculated LDL is estimated from the following equation: Total Cholesterol − HDL − (Triglycerides/5).

Results

Means, standard deviations, and ranges are reported for each gender in Table 1.

Multivariate Analyses

Three hierarchical multiple regression models were used to examine the relationship among demographic, stress, coping, lifestyle behaviors, and cardiovascular risk variables, as well as the interactions between gender and coping or lifestyle behaviors. Continuous variables were centered, and interaction terms were created using methods described by Aiken and West [21]. Calculated LDL, SBP, and DBP were used as dependent variables (see Table 3, DBP is not included in table format as it was highly correlated with SBP, r = 0.64, p < 0.001). Block 1 consisted of gender, age, and ethnicity (i.e., dummy coded African American, Latin American, and “Other” (Native American, Asian American, or Other)). Block 2 consisted of the addition of daily hassles as a measure of stress. Block 3 consisted of the addition of coping strategies, including positive/problem-focused, social support, and avoidant coping. Block 4 consisted of the addition of lifestyle behaviors (BMI, cigarette use, number of times exercised per week, and number of alcoholic beverages consumed per week). Block 5 consisted of the addition of the interactions between gender and coping or lifestyle behaviors.

Cholesterol

In blocks 1 and 2, age was a significant predictor of the variance in calculated LDL. In block 3, age and greater use of social support were significant predictors of calculated LDL. In block 4, age, non-African American ethnicity, greater use of social support, greater BMI, and less frequent exercise use were significant predictors of the variance in calculated LDL. In block 5, age and non-African American ethnicity were significant predictors of the variance in calculated LDL.

Blood Pressure

In blocks 1, 2, and 3, male gender and age were significant predictors of the variance in SBP. In block 4, male gender and greater BMI were significant predictors of the variance in SBP. In block 5, male gender, greater BMI, less frequent use of exercise, the interaction between gender and avoidant coping, and the interaction between gender and exercise were significant predictors of the variance in SBP.

In blocks 1 and 2, male gender, age, and non-Latino(a) ethnicity were significant predictors of the variance in DBP. In block 3, only male gender and age were significant predictors of the variance in DBP. In blocks 4 and 5, male gender, non-Latino(a) ethnicity, and greater BMI were significant predictors of the variance in DBP.

Gender Differences

Independent samples t-tests revealed that males had higher SBP (t(286) = 6.62, p < 0.001) and DBP (t(293)=4.89, p < .001) than did females (see Table 1). Men also reported higher alcohol consumption per week (t(293) = 3.09, p < 0.01) than did women. Regarding psychological measures, females reported greater stress (t(271) = −2.12, p < 0.05) and greater use of social support as a coping strategy (t(296) = −4.15, p < 0.001) than did males.

Bivariate correlations by gender (see Table 2) revealed that for males, age was positively related to calculated LDL (r = 0.27, p < 0.05). BMI was positively associated with SBP (r = 0.50, p < 0.001), less frequent exercise was associated with SBP (r = −0.31, p < 0.01), and BMI was positively associated with DBP (r = 0.30, p < 0.01). For females, age (r = 0.24, p < 0.01), social support (r = 0.20, p < 0.01), and BMI (r = 0.19, p < 0.01) were positively related to calculated LDL; age (r = 0.26, p < 0.001) and BMI (r = 0.38, p < 0.001) were positively associated with SBP; and age (r = 0.16, p < 0.05) and BMI (r = 0.30, p < 0.001) were positively associated with DBP.

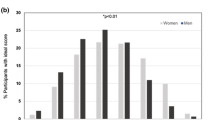

Two significant interactions were found using hierarchical regression analyses (Table 3). Scores were categorized as low (one standard deviation below the mean), moderate (the mean), and high (one standard deviation above the mean [21]). Examination of the interactions revealed that for men, greater use of avoidant coping was associated with lower SBP, while for women, greater use of avoidant coping was associated with a slight increase in SBP (see Fig. 1). In addition, for men, as exercise frequency increased, SBP decreased; however, for women, exercise did not have a significant effect on SBP (see Fig. 2).

Analyses were also conducted to examine mediation (using gender as both the predictor variable and as the mediator [22]); however, criteria were not met to suggest that gender, coping, or lifestyle behaviors served as a mediator within our sample.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships among coping strategies, lifestyle behaviors, and cardiovascular risks in a non-medical sample of university students. Gender differences were also examined because of known physiological and psychological differences between men and women. Our findings suggest that lifestyle and coping behaviors play different roles in men and women’s cardiovascular functioning.

Greater use of avoidant coping was associated with lower SBP in men, while a slight increase in SBP for women. Avoidant coping comprises strategies such as self-blame, using substances to cope, and behavioral disengagement [18]. Men report greater use of avoidance as a coping strategy than women [23]. Men also reported less stress than women in our study, consistent with literature documenting gender differences in perception and response to stress [10]. It is possible that avoidance of stress and problems in the short-term is associated with healthier cardiovascular functioning in young men, but it is unclear whether avoidance continues to play a protective role over time. Longitudinal and experimental designs are needed to determine whether avoidant coping is protective against cardiovascular disease in men.

Our results suggest that less frequent physical activity or exercise was associated with greater SBP for men, but not for women. Exercise frequency was associated with a 6-mm Hg increase in SBP for men, while no significant difference was present in women. There does not appear to be a gender difference in benefits received through exercise [24], though men typically report higher levels of exercise than females [6]. These findings are consistent with the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute [25], which stipulates that physical inactivity is a known risk factor for CVD, but it suggests the possibility that exercise may impact different cardiovascular mechanisms in men and women, though additional research is necessary to confirm.

Greater use of social support was associated with higher cholesterol in the overall model, but did not remain as a significant predictor when gender interactions were included. In bivariate correlations by gender, social support was associated with higher cholesterol in women, but not in men. Social support includes emotional support, instrumental support, and venting. Instrumental support involves attempting to get advice or support from others as well as actually receiving advice, while emotional support involves getting comfort and understanding from others. Venting includes expressing negative feelings [18]. Further analyses for women revealed that two items representing instrumental support and one item representing emotional support were positively associated with calculated LDL. All three items encompass receiving or attempting to receive support from others.

In a narrative review of the link between social support and physical health, Uchino [26] drew a distinction between perceived and received social support. Perceived support appears to bear most of the positive associations with health, while received support has either mixed or negative health associations. Received support refers to the actual receipt of resources, while perceived support refers to an individual’s potential access to support [26]. Asking for and receiving advice from others may reduce an individuals’ sense of independence or autonomy [26]. Further, received support may not include support that is perceived as nurturing and supportive [27].

Men reported greater alcohol use in our sample than did women, though alcohol use was not a significant predictor of cardiovascular risk when other variables were considered. Men are twice as likely as women to meet criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, and more likely to report alcohol use or binge drinking than are women [28]. Heavy drinking (e.g., more than three drinks per day) is associated with cardiovascular complications such as cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and stroke [29]. Alcohol use has been directly associated with a marker of atherosclerosis in a large sample of healthy young adults, independent of other factors such as BP or cholesterol [30]. Given the higher rate of alcohol use in men and potential additive health complications, alcohol use in male college students needs to be assessed and addressed proactively.

BMI was a significant predictor of cardiovascular risks for both men and women in bivariate and multivariate analyses. BMI was associated with higher SBP in men and women, as well as higher cholesterol in women. This is consistent with a study by Ford et al. [31] who also found BMI or obesity to be a predictor of heightened BP and cholesterol in men and women. To offset the influence BMI and obesity have on the cardiovascular system in both men and women, educational interventions regarding diet and nutrition need to be implemented into college settings, ideally as a required part of the curriculum.

Limitations

Our sample was a convenience sample of college students enrolled in psychology courses and is limited by cross-sectional correlational data that does not allow causal inference. Although the purpose of the study was to examine cardiovascular risk in young adults, prior to disease onset, our findings may not generalize to the population at large or young adults outside of an academic setting. Future research needs to examine the complex relationships among demographic variables such as gender, coping, and lifestyle behaviors through experimental and longitudinal designs using large, diverse, and representative samples. The study is also limited by reliance on self-report information for demographic, coping, and lifestyle behaviors (i.e., weight and height to calculate BMI), as well as exclusion criteria. A more thorough assessment of lifestyle behaviors (e.g., amount and frequency of alcohol use per day) is necessary to identify the relationships among these variables and cardiovascular functioning.

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

Understanding how college students manage their demands and cope with stress sets the stage for understanding the developmental process of CVD. Coping strategies can be taught and altered, providing a method of intervention [9, 32]. If adaptive strategies such as exercise are increased and maladaptive strategies such as alcohol use are reduced at a young age, psychological distress may be reduced, and CVD may be less likely to develop. Our study suggests that coping strategies add to the prediction of cardiovascular risk above and beyond the contributions of lifestyle behaviors in college students. Although seeking social support is generally considered adaptive for cardiovascular health, the present results suggest that social support may contribute to higher cholesterol. Special attention to the specific type of support experienced by individuals is needed in order to tailor effective and health promoting interventions. Though greater use of avoidant coping was associated with lower BP for men, it is unknown why this relationship exists and additional examination would be required prior to implementing clinical recommendations.

References

Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e21–e181.

Heron M, Hoyert D, Murphy S, Xu J, Kochanek K, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57:14.

Pleis J, Lethbridge-Çejku M. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2006. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2007;10:235.

Sarafino E. Health psychology: biopsychosocial interactions. 6th ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken, NJ; 2008.

Mensah, G, Brown, D, Croft, J, Greenlund, K. Major coronary risk factors and death from coronary heart disease: baseline and follow-up mortality data from the Second National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). Third report of the expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (ATP III final report). National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Web site. 2011. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/atp3full.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2011.

Eaton D, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth risk behavior surveillance: United States. MMWR. 2008;57:1–131.

Buckingham J. Glucocorticoids: exemplars of multi-tasking. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:S258–68.

Dedovic K, Duchesne A, Andrews J, Engert V, Pruessner J. The brain and the stress axis: the neural correlates of cortisol regulation in response to stress. Neuroimage. 2009;47:864–71.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984.

Kajantie E, Phillips D. The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:151–78.

Wang J, Korczykowski M, Rao H, Fan Y, Pluta J, Gur R, McEwen B, Detre J. Gender difference in neural response to psychological stress. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2:227–39.

Yeh S, Huang C, Chou H, Wan T. Gender differences in stress and coping among elderly patients on hemodialysis. Sex Rol. 2009;60:44–56.

Uchino B. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Int J Behav Med. 2006;29:377–87.

Sollár T, Sollárová E. Proactive coping from the perspective of age, gender and education. Stud Psychol. 2009;51:161–5.

Robb C, Small B, Haley W. Gender differences in coping with functional disability in older married couples: the role of personality and social resources. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12:423–33.

Doster J, Purdum M, Martin L, Goven A, Moorefield R. Gender differences, anger expression, and cardiovascular risk. J Ment Nerv Disord. 2009;197(7):552–4.

Kuczmarski MF, Kuczmarski RJ, Najjar M. Effects of age on validity of self-reported height, weight, and body mass index: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:28–34.

Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the Brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92–101.

Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267–83.

Delongis A, Folkman S, Lazarus R. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: psychological and social resources as mediators. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:486–95.

Aiken L, West S. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications, Inc. Thousand Oaks, CA; 1991.

Frazier PA, Tix AP, Baron KE. Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. J Couns Psychol. 2004;51:115–34.

Landow MV. College students: mental health and coping strategies. Hauppauge: Nova Science; 2006.

Navalta JW, Sedlock DA, Park KS, McFarlin BK. Neither gender nor menstrual cycle phase influences exercise-induced lymphocyte apoptosis in untrained subjects. Appl Physiol, Nutr, Metab. 2007;32:481–6.

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2009. Web Site: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/. Accessed January 5, 2009.

Uchino B. Understanding the links between social support and physical health: a lifespan perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2009;4:236–55.

Holt-Lunstad J, Uchino B, Smith T, Hicks A. On the importance of relationship quality: the impact of ambivalence in friendships on cardiovascular functioning. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:278–90.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. August 2, 2007. The NSDUH report: gender differences in alcohol use and alcohol dependence or abuse: 2004 and 2005. Rockville, MD.

Klatsky, AL. Alcohol and cardiovascular health. Physiol Behav, December 31, 2009.

Juonala M, Viikari J, Kahonen M, et al. Alcohol consumption is directly associated with carotid intima-media thickness in Finnish young adults: the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:93–8.

Ford C, Nonnemaker J, Wirth K. The influence of adolescent body mass index, physical activity, and tobacco use on blood pressure and cholesterol in young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:576–83.

Steinhardt M, Dolbier C. Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. J Am Coll Health. 2008;56:445–53.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, L.A., Critelli, J.W., Doster, J.A. et al. Cardiovascular Risk: Gender Differences in Lifestyle Behaviors and Coping Strategies. Int.J. Behav. Med. 20, 97–105 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-011-9204-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-011-9204-3