Abstract

Background

Physical inactivity leads to higher morbidity and mortality from chronic non-communicable diseases. In high income countries, studies have measured school population level physical activity and substance use, but comparable data are lacking from most African countries.

Purpose

To study the relationship between self-reported leisure time physical activity frequency and sedentary behavior and alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use behaviors among school children.

Method

A cross-sectional survey was conducted with the total sample of 24,593 school children aged 13 to 15 years from nationally representative samples from eight African countries. Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to assess the relationship between physical activity frequency, six measures of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use, socioeconomic status, and mental health variables.

Results

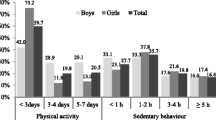

In all, only 14.2% of the school children were frequently physically active (5 days and more in a week, at least 60 min/day) during leisure time; this was significantly higher among boys than girls. Ugandan and Kenyan school children were most physically active (17.7% and 16.0%, respectively), and Zambian and Senegalese the least (9.0% and 10.9%, respectively). Frequency of alcohol consumption and higher socioeconomic status were significantly associated with leisure time physical activity, while tobacco, illicit drug use, and mental health variables were not. Leisure time sedentary behavior of five and more hours spent sitting on a usual day were highly associated with all substance use variables.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that leisure time physical activity frequency is associated with frequency of alcohol use and not with tobacco and illicit drug use, and leisure time sedentary behavior is highly associated with alcohol, tobacco, and drug use among adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to Warburton, Nicol, and Bredin [1], “there is irrefutable evidence of the effectiveness of regular physical activity in the primary and secondary prevention of several chronic diseases (e.g., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, hypertension, obesity, depression and osteoporosis) and premature death.”

A number of cross-sectional studies among adolescents found an association between physical inactivity and substance use: smoked more on a daily basis [2], smoking and other tobacco use, as well as alcohol consumption during the previous 30 days [3], alcohol consumption [4], cigarette smoking, marijuana use [5], initiation of cigarette smoking and alcohol use [6], cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, and marijuana [7].

Other cross-sectional studies seem to suggest that frequent exercisers may also engage in more substance use. Moore and Werch [8] found among eighth grade youth from three schools that participation in school-sponsored, male-dominated sports appeared to be associated with an increased substance use risk for males, whereas out-of-school, mixed-gender sports appeared to be associated with an increased substance use risk for females, and among American college students, Moore and Werch [9] found that frequent exercisers drank significantly more often and a significantly greater quantity than did infrequent exercisers. However, frequent exercisers smoked cigarettes significantly less often than did infrequent exercisers.

Longitudinal studies among adolescents also found an association between physical inactivity and later substance use: excess alcohol use, illicit drug use [10], and adult smoking [11].

Various cross-sectional and prospective studies seem to indicate that physical activity is linked to engaging in other (than less substance use) positive health behaviors such as fruit and vegetable consumption, wearing a seat belt [5], substantially reduced risk for some, but not all, mental disorders, and also seems to reduce the degree of comorbidity [12].

Some thinking has led to recommend exercise programs for youth as intervention to help them avoid initiating risk-taking behaviors such as substance abuse [5, 6] and that individuals who choose to engage in one health-promoting behavior such as physical activity would not simultaneously engage in health-damaging behaviors such as substance misuse [9].

Little information is available about the relationship between physical activity and substance use among an adolescent population in Africa. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the relationship between self-reported leisure time physical activity frequency and sedentary behavior and alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use behaviors among school children in African countries.

Method

Description of Survey and Study Population

This study involved secondary analysis of existing data from the Global School-Based Health Survey (GSHS) from eight African countries (Botswana, Kenya, Namibia, Senegal, Swaziland, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe). All African countries from which GSHS datasets were publicly available were included in the analysis. Details and data of the GSHS can be accessed at http://www.who.int/chp/gshs/methodology/en/index.html. From all but one country, national samples were included, while from Zimbabwe, three areas were included: Harare, Bulawayo, and Manicaland. The aim of the GSHS is to collect data primarily from students of age 13 to 15 years. A two-stage cluster sample design was used to collect data to represent all students in grades 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 in the country. At the first stage of sampling, schools were selected with probability proportional to their reported enrollment size. In the second stage, classes in the selected schools were randomly selected and all students in selected classes were eligible to participate irrespective of their actual ages. Students self-completed the questionnaires to record their responses to each question on a computer-scannable answer sheet.

Measures

The GSHS ten core questionnaire modules address the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among children and adults worldwide: tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use; dietary behaviors; hygiene; mental health; physical activity; sexual behaviors that contribute to HIV infection, other sexually transmitted infections, and unintended pregnancy; unintentional injuries and violence; hygiene; protective factors and respondent demographics [13].

Physical Activity

Leisure time physical activity was assessed by asking participants: “Physical activity is any activity that increases your heart rate and makes you get out of breath some of the time. Physical activity can be done in sports, playing with friends, or walking to school. Some examples of physical activity are running, fast walking, biking, dancing, football. Do not include your physical education or gym class.” “During the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day?” and “During a typical or usual week, on how many days are you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day?” “The mean number of days from the past week and a typical week were used as an index of participation.”

Leisure time sedentary behavior was assessed by asking participants about the time they spend mostly sitting when not in school or doing homework: “How much time do you spend during a typical or usual day sitting and watching television, playing computer games, talking with friends, or doing other sitting activities.”

Substance Use Variables

Smoking cigarettes and the use of any other form of tobacco such as snuff or chewed tobacco: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes or use other forms of tobacco?” Response options were from 1 = 0 days to 7 = all 30 days; coded 1 = 1 or 2 to all 30 days and 0 = 0 days.

Alcohol use was measured with three variables: (a) “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink containing alcohol?” Response options were from 1 = 0 days to 7 = all 30 days; coded 1 = 1 or 2 to all 30 days, and 0 = 0 days. (b) “During the past 30 days, on the days you drank alcohol, how many drinks did you usually drink per day?” Response options were from 1 = did not drink alcohol to 6 = 5 or more drinks; coded 6 = 1, 5 or more drinks and 1–5 = 0. (c) Excessive drinking: “During your life, how many times did you drink so much alcohol that you were really drunk?” Response options were from 1 = 0 times to 4 = 10 or more times; coded 1 = 1 or 2 to 10 or more times and 0 = 0 times.

Drugs

“During your life, how many times have you used drugs, such as glue, benzene, marijuana, cocaine, or mandrax?” Response options were from 1 = 0 times to 4 = 10 or more times; coded 1 = 1 or 2 to 10 or more times and 0 = 0 times.

Other Variables Included were Hunger as a Measure of Socioeconomic Status and Mental Health Variables

Hunger

A measure of hunger was derived from a question reporting the frequency that a young person went hungry because there was not enough food at home in the past 30 days (response options were from 1 = never to 5 = always; coded 1 = most of the time or always and 0 = never, rarely, or sometimes).

Lonely

“During the past 12 months, how often have you felt lonely?” Response options were from 1 = never to 5 = always; coded 1 = most of the time or always and 0 = never, rarely, or sometimes.

Worried

“During the past 12 months, how often have you been so worried about something that you could not sleep at night?” Response options were from 1 = never to 5 = always; coded 1 = most of the time or always and 0 = never, rarely, or sometimes.

Depression

“During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing your usual activities?” Response option 1 = yes and 2 = no; coded 1 = 1 and 2 = 0.

Data Analysis

In order to compare study samples across countries, each country sample was restricted to the age group 13 to 15 years, younger and older participants were excluded from the analyses. Data analysis was performed using STATA software version 10.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). This software has the advantage of directly including robust standard errors that account for the sampling design, i.e., cluster sampling owing to the sampling of school classes. In further analysis, the physical activity variable was recoded into two categories: physically inactive (four and less days physically active in a week = 0) and frequently physically active (five and more days physically active in a week = 1). Associations between substance use, socioeconomic status, mental health, and physical activity among school children were evaluated calculating odds ratios (OR). Logistic regression was used for the evaluation of the impact of explanatory variables for physical activity (binary dependent variable). In the analysis, weighted percentages are reported. The reported sample size refers to the sample that was asked the target question. The two-sided 95% confidence intervals are reported. The p value ≤5% is used to indicate statistical significance. Both the reported 95% confidence intervals and the p value are adjusted for the multistage stratified cluster sample design of the study.

Results

Sample Characteristics, Physical Activity, and Substance Use

The total sample included 24,593 school children aged 13 to 15 years from eight African countries. There were slightly more female (57.1%) than male (42.9%) school children. In all, only 14.2% of the school children were frequently physically active (5 days and more in a week, at least 60 min/day) during leisure time (including walking to school); this was significantly higher among boys than girls. Ugandan and Kenyan school children were most frequently physically active (17.7% and 16.0%, respectively), and Zambian and Senegalese the least (9.0% and 10.9%, respectively). Tobacco use was 10.4% smoking cigarettes and 11.4% the use of other tobacco products in the past month for the whole sample. Namibian school children were the most frequent smokers (16.1%) and users of other tobacco products (31.8%), while Ugandan school children were the lowest tobacco users (4.3% and 5.5%, respectively). Overall, 15% reported past month alcohol use, 1.2% would typically drink five or more drinks in a day, and 18.8% had ever been drunk. The highest frequency of alcohol use was reported from Zambian and Namibian school children (42.3% and 32.8% past month, 5.6% and 3.7% typically five or more drinks in a day, and 42.8% and 31.8% had ever been drunk, respectively), and the lowest frequency among Senegalese school children (3.2%, 0.2% and 4.8%, respectively). Similarly, lifetime illegal drug use was highest among Zambian and Namibian school children (38.1% and 28.8%, respectively) and the lowest among Senegalese school children (0.6%). Boys significantly more often than girls reported tobacco and alcohol use, while there was no significant gender difference for lifetime illegal drug use (see Table 1).

Leisure Time Physical Activity and its Relationship with Substance Use and Other Variables

In univariate regression analyses adjusted by gender, frequency of alcohol consumption, amount of alcohol consumption, and frequency of using other tobacco products were associated with frequent physical activity and frequency of smoking cigarettes, drinking heavily, and frequency of illicit drug use were not associated with frequent physical activity. In multivariate regression analysis adjusted by gender, only frequency of alcohol consumption was still associated with frequent leisure time physical activity (see Table 2).

Furthermore, univariate logistic regression found that poverty (went hungry) was inversely associated with frequent leisure time physical activity, while mental health variables (loneliness, anxiety, and depression) were not associated with frequent leisure time physical activity (see Table 3).

Leisure Time Physical Activity and Time Spent Sitting Levels in Relation to Substance Use

Regular and frequent leisure time physical activity levels were associated with frequency of alcohol use, and five and more hours spent sitting on a usual day during leisure time were highly associated with all substance use variables (see Table 4).

Discussion

The current investigation explores leisure time physical activity and sedentary behavior and its relationship to substance use among in-school adolescents from eight African countries. Low leisure time physical activity levels were found: 14.2% of the school children were frequently and regularly physically active (5 days and more in a week and 3–4 days, respectively, at least 60 min/day) during leisure time. Studies from other African countries seem to confirm relatively low physical activity levels among adolescents, e.g., in South African school children (age 13 to 19 years) more than one third (37.5%) of the students engaged in insufficient physical activity (<3 days participation in at least 20 min of activity which constitutes vigorous physical exercise in the past week and/or <30 min of activity which constitutes moderate physical exercise on at least 5 days in the past week) [14]. Prevalence rates of 14.2% frequently physically active during leisure time found in this study were (using the same physical activity measure but including school activities) generally probably lower than those found among 11- to 15-year-old school children in the WHO European Region and North America from the Health Behaviour in School Children (HBSC) survey of 34% [15, 16]. This study excluded and the HBSC survey included school activities such as school sports in the physical activity assessment. Since, overall, physical activity during the school day appears to be lower than that out of school [17], African children seem still to be less physically active than Euro-North American children.

This study found cross-national variations in the prevalence of frequent leisure time physical activity, Ugandan and Kenyan school children were most frequently physically active (17.7% and 16.0%, respectively) and Zambian and Senegalese school children the least (9.0% and 10.9%, respectively). Possible reasons for such country differences could be urbanization rate such that participants from rural areas have higher participation in physical activity (including walking to school) than adolescents from urban areas. Local studies conducted in Benin [18], Kenya [19], and Senegal [20] seem to confirm that adolescents from rural areas have higher physical activity levels than those from urban areas. Among the study countries, Ugandan and Kenyan school children were most frequently physically active and also had the lowest urbanization levels (Uganda = 13% and Kenya = 21%) compared to all other participating countries, with urbanization levels ranging from 35% to 59% [21].

The study found that frequency of alcohol consumption was significantly associated with leisure time physical activity. This finding seems to concur with some studies among college students [8] but not with other studies on adolescent school children [3, 4, 6, 10]. While this study found that tobacco and illicit drug use were not associated with physical activity, other studies found an inverse association between physical activity and tobacco and illicit drug use [2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11]. Furthermore, this study found that higher socioeconomic status was associated with participation in more frequent physical activity. This concurs with a review by Gidlow et al. [22] who found a consistent association between higher prevalence and higher levels of leisure time or moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity and higher socioeconomic status. Chinn et al. [23] have identified the lower socioeconomic position as a barrier to physical activity and as a target for health promotion.

Furthermore, this study found that 28.7% spent three and more hours and 11.2% spent five and more hours, respectively, sitting on a usual day as part of sedentary leisure behavior. Among South African school children (age 13 to 19 years), similar rates of hours spent sitting was found; nationally, 25.2% of learners watched television or played video or computer games for more than 3 h/day [24], and among 11- to 15-year-old school children in the WHO European Region and North America HBSC survey, 26% reported four or more hours a day of television use on each weekday and 45% at weekends [25].

This study found that five and more hours spent sitting on a usual day were highly associated with all substance use variables. This has implications for the promotion of physical activity and prevention of substance misuse. Katzmarzyk, Church, Craig, and Bouchard [26] demonstrated a dose–response association between sitting time and mortality from all causes and cardiovascular disease, independent of leisure time physical activity. In addition to the promotion of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, children should be discouraged sitting for extended periods [27].

More research is also needed on the cognitive, social, and environmental factors that may influence physical activity, time spent sitting, and substance use levels among adolescents [9]. Key determinants of physical activity and sedentariness in youth include demographic factors (such as the greater likelihood of activity in younger people, particularly boys), psychological factors (such as perceived competence, self-efficacy, goal orientation/motivation, and enjoyment), social factors (such as encouragement from parents, siblings, and peers), and the physical environment (such as the availability of facilities and programs). Moreover, further research is needed examining the correlates of insufficient physical activity and sedentary behaviors to develop effective interventions that may help children and adolescents diminish the time they spend on inactive behaviors [28, 29].

Physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyle are associated with being overweight in children and adults [30]. The prevalence of childhood obesity has reached alarming levels, affecting virtually both developed and developing countries, with the prevalence of being overweight among children under the age of 5 in Africa and Asia averaging well below 10% and in the Americas and Europe above 20% [31]. Thus, it is imperative to consider exercise and physical activity as a means to prevent and combat the childhood obesity epidemic [30]. Increasing physical activity participation and decreasing television viewing should be the focus of strategies aimed at preventing and treating overweight and obesity in adolescents and youth [32].

Many programs to increase physical activity have been evaluated in high-income countries where “leisure time physical activity” is the most frequent domain for interventions. In African countries, different kinds of interventions targeting “total physical activity” in the domains of work, active transport, reduced sitting time, as well as leisure time physical activity promotion are needed [33]. In considering possible solutions, Bauman, Finegood, and Matsudo [33, p. 309] suggest key sets of actions:

[i] efforts to disseminate individual-level behavior change programs to reach much larger populations rather than volunteers, [ii] social marketing and mass communication campaigns to change social norms in the community and among professionals and policymakers, [iii] efforts to influence the social and physical environment to make them more conducive to physical activity, and [iv] the development and implementation of national physical activity plans and strategies, with sufficient timelines and resources to achieve measurable change.

Limitations of the Study

This study had several limitations. Firstly, the GSHS only enrolls adolescents who are in school. School-going adolescents may not be representative of all adolescents in a country as the occurrence of physical activity and substance use may differ between the two groups. As the questionnaire was self-completed, it is possible that some study participants may have misreported either intentionally or inadvertently on any of the questions asked. Intentional misreporting was probably minimized by the fact that study participants completed the questionnaires anonymously. Furthermore, the self-report of physical activity should be interpreted with caution; it is possible that respondents over-reported physical activity, as found in other studies among adolescents [34]. The questionnaire used in this study measured mental distress variables with single items, which are quite limited in their use as quantitative indices. Furthermore, this study was based on data collected in a cross-sectional survey. We cannot, therefore, ascribe causality to any of the associated factors in the study [35]. Prospective studies are required to follow-up physical activity and their influence on substance use.

References

Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174(6):801–9.

Vindfeld S, Schnohr C, Niclasen B. Trends in physical activity in Greenlandic schoolchildren, 1994–2006. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009;68(1):42–52.

Kristjansson AL, Sigfusdottir ID, Allegrante JP, Helgason AR. Social correlates of cigarette smoking among Icelandic adolescents: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:86.

Tur JA, Puig MS, Pons A, Benito E. Alcohol consumption among school adolescents in Palma de Mallorca. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:243–9.

Pate RR, Heath GW, Dowda M, Trost SG. Associations between physical activity and other health behaviors in a representative sample of US adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(11):1577–81.

Aaron DJ, Dearwater SR, Anderson R, Olsen T, Kriska AM, Laporte RE. Physical activity and the initiation of high-risk health behaviors in adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27(12):1639–45.

Winnail SD, Valois RF, McKeown RE, Saunders RP, Pate RR. Relationship between physical activity level and cigarette, smokeless tobacco, and marijuana use among public high school adolescents. J Sch Health. 1995;65(10):438–42.

Moore MJ, Werch CE. Sport and physical activity participation and substance use among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36(6):486–93.

Moore MJ, Chudley E, Werch CE. Relationship between vigorous exercise frequency and substance use among first-year drinking college students. J Am Coll Health. 2008;56(6):686–90.

Korhonen T, Kujala UM, Rose RJ, Kaprio J. Physical activity in adolescence as a predictor of alcohol and illicit drug use in early adulthood: a longitudinal population-based twin study. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2009;12(3):261–8.

Kujala UM, Kaprio J, Rose RJ. Physical activity in adolescence and smoking in young adulthood: a prospective twin cohort study. Addiction. 2007;102(7):1151–7.

Ströhle A, Höfler M, Pfister H, Müller AG, Hoyer J, Wittchen HU, et al. Physical activity and prevalence and incidence of mental disorders in adolescents and young adults. Psychol Med. 2007;37(11):1657–66.

CDC. The Global School and Health Survey background. http://www.cdc.gov/gshs/background/index.htm. Accessed 15 April 2009.

Amosun SL, Reddy PS, Kambaran N, Omardien R. Are students in public high schools in South Africa physically active? Outcome of the 1st South African National Youth Risk Behaviour Survey. Can J Public Health. 2007;98(4):254–8.

WHO Regional Office for Europe. Young people's health in context. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: international report from the 2001/2002 survey, Copenhagen, Denmark. http://www.hbsc.org/publications/reports.html (2004). Accessed 3 November 2007.

Roberts C, Tynjälä J, Komkov A. Physical activity. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2004. p. 90–7.

Gidlow CJ, Cochrane T, Davey R, Smith H. In-school and out-of-school physical activity in primary and secondary school children. J Sports Sci. 2008;26(13):1411–9.

Gouthon P, Falola JM, Aremou M, Dagba J, Tossou J, Legba J, et al. Comparison of physical activity among Beninese adolescents attending schools in rural, suburban and urban areas: physical education and health. AJPHERD. 2007;13(2):196–208.

Larsen HB, Christensen DL, Nolan T, Søndergaard H. Body dimensions, exercise capacity and physical activity level of adolescent Nandi boys in western Kenya. Ann Hum Biol. 2004;31(2):159–73.

Garnier D, Ndiaye G, Bénéfice E. Influence of urban migration on physical activity, nutritional status and growth of Senegalese adolescents of rural origin. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2003;96(3):223–7.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). State of world population 2007. New York: UNFPA; 2007.

Gidlow C, Johnston LH, Crone D, Ellis N, James D. A systematic review of the relationship between socio-economic position and physical activity. Health Educ J. 2006;65:338–67.

Chinn DJ, White M, Harland J, Drinkwater C, Raybould S. Barriers to physical activity and socioeconomic position: implications for health promotion. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:191–2.

Reddy SP, Panday S, Swart D, Jinabhai CC, Amosun SL, James S, et al. Umthenthe Uhlaba Usamila—the South African youth risk behaviour survey 2002. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council; 2003.

Todd J, Currie D. Sedentary behaviour. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2004. p. 98–109.

Katzmarzyk PT, Church TS, Craig CL, Bouchard C. Sitting time and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(5):998–1005.

Jago R, Anderson CB, Baranowski T, Watson K. Adolescent patterns of physical activity differences by gender, day, and time of day. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(5):447–52.

Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(5):963–75.

Van Der Horst K, Paw MJ, Twisk JW, Van Mechelen W. A brief review on correlates of physical activity and sedentariness in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1241–50.

Dugan SA. Exercise for preventing childhood obesity. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2008;19(2):205–16.

Kosti RI, Panagiotakos DB. The epidemic of obesity in children and adolescents in the world. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2006;14(4):151–9.

Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Boyce WF, Vereecken C, Mulvihill C, Roberts C, et al. Comparison of overweight and obesity prevalence in school-aged youth from 34 countries and their relationships with physical activity and dietary patterns. Obes Rev. 2005;6(2):123–32.

Bauman A, Finegood DT, Matsudo V. International perspectives on the physical inactivity crisis—structural solutions over evidence generation? Prev Med. 2009;49:309–12.

Shiely F, MacDonncha C. Meeting the international adolescent physical activity guidelines: a comparison of objectively measured and self-reported physical activity levels. Ir Med J. 2009;102(1):15–9.

Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Causation and causal inference in epidemiology. Am J Public Health. 2005;95 Suppl 1:S144–50.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the World Health Organization (Geneva) for making the data available for analysis. I also thank the Ministries of Education and Health and the study participants for making the Global School Health Survey in the eight African countries possible. The governments of the respective study countries and the World Health Organization did not influence the analysis nor did they have influence on the decision to publish these findings.

Competing interests

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peltzer, K. Leisure Time Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior and Substance Use Among In-School Adolescents in Eight African Countries. Int.J. Behav. Med. 17, 271–278 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-009-9073-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-009-9073-1