Abstract

Mobile health services have become increasingly important for people, especially for the elderly. Despite the potential benefits, there are challenges and barriers for the elderly in adopting mobile health services. Drawing upon the dual factor model, we investigate the enablers and the inhibitors of the elderly mobile health service adoption behaviour. We also address two typical characteristics of elderly users—technology anxiety and dispositional resistance to change—to understand the antecedents of the enablers and the inhibitors. The hypothesized model is empirically tested using data collected from a field survey of 204 customers of a large elderly service providing company in China. The key findings include: (1) resistance to change influences perceived usefulness but does not influence perceived ease of use and adoption intention; (2) technology anxiety is negatively associated with perceived ease of use but positively associated with resistance to change; (3) dispositional resistance to change is negatively associated with perceived ease of use but positively associated with resistance to change. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With the rapid advancement of mobile technology, mobile health (m-health) has been increasingly advocated and promoted by governmental agencies, companies, and hospitals. Compared to the traditional electronic health (e-health) which may heavily rely on the computer and Internet, m-health can leverage the advantages of wireless cellular communication capability (e.g., mobility) and relatively small size and low weight (e.g., portability) to make the health services to be delivered with less temporal and spatial constraints (Free et al. 2010). Because of these special strengths, m-health has been widely used in particular activities in health care and public health sectors, especially for those health services that require urgent, real time, and location-based response (Fukuoka et al. 2011).

Mobile health (m-health) services for the elderly are particularly important given that the aging population has become a global issue. For instance, according to the annual statistics of Chinese population, the percentage of old people (older than 65 years of age) rose to 8.5 % in 2009 from 5.6 % in 1990, and it is expected to keep sustained growth until 2050.Footnote 1 While there are potential benefits of mobile healthcare services, there are challenges and barriers for this special user population (e.g., elderly users) in adopting them. According to our interviews with Chinese companies and the elderly, there are two critical barriers for them. First, it is always difficult and costly for the elderly to learn how to operate new devices. They are worried about the negative consequences induced by their wrong operations and thus avoid using new devices. Second, they would like to keep to their routines and do not like any activity that can change their life style. Although they know they could expect benefits from using mobile healthcare services, changes in their life scare them.

This suggests that understanding the mobile health service adoption behaviour should pay attention to not only the benefits brought by the services but also to the barriers inhibiting the adoption behaviour. However, prior studies on the electronic health technology acceptance behaviour have stressed more on the benefits such as the perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use (Cocosila and Archer 2010; Or and Karsh 2009) than on the barriers. To fill this research gap, drawing upon the dual factor model of technology adoption (Cenfetelli 2004), we try to investigate both the enablers and the inhibitors of technology acceptance behaviour under the context of m-health services. In particular, consistent with the prior literature on technology acceptance, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use (Davis et al. 1989; Venkatesh and Morris 2003) are treated as two enablers, while users’ resistance to change is regarded as the inhibitor according to our preliminary interview. It is worth noting that, although resistance to change has been investigated in the e-health context, they have been studied from the perspective of physicians by focusing on the physicians’ resistance to the change in work style (Bhattacherjee and Hikmet 2007; Oded Nov and Schecter 2012). However, according to the classification of Free et al. (2010), there are four types of m-health services in terms of the users including researchers, professionals or physicians, patients, and general population. In our study, the general population is the users of the m-health services, thus the change in life style rather than work style becomes the source of resistance. The difference in research context calls for revisiting the role of resistance to change.

To help the practitioners to establish certain strategies to removing the inhibitors and enlarging the enablers, it is necessary to understand the determinants of the enablers and the inhibitors within the context of elderly users. To fill this research gap, two particular characteristics of elderly users namely technology anxiety (Dyck et al. 1998; Laguna and Babcock 1997) and dispositional resistance to change (Oreg 2003, 2006) are examined. Technology anxiety reflects people’s disposition to using a new technology, while dispositional resistance to change reflects people’s disposition to handling changes. These two constructs respectively capture the technology- and personality-related dispositions of elderly users. They are supposed to influence users’ perceptions of the enablers and inhibitors which in turn affect users’ intention to adopt the mobile health services. Thus, the research objective of the study can be clearly stated as to understand the enablers and the inhibitors of users’ acceptance of mobile health services and the antecedents of these enablers and inhibitors.

The paper contribute to the m-health literature in several ways. First, it is the first study, to our knowledge, that empirically tests both the enablers and the inhibitors of the technology acceptance behaviour within the m-health context, enriching the m-health literature by introducing the role of inhibitors. Second, the paper captures the two key characteristics of elderly users (e.g., technology anxiety and dispositional resistance to change) to understand the antecedents of the enablers and inhibitors, developing a m-health adoption model specific to the population of elderly users. Third, the paper separates the personality factor and the status factor of resistance to change, advancing theoretical understanding on the different roles of these two types of factors.

Literature review

Mobile health services

Mobile health (m-health) is defined as the emerging mobile communications and network technologies for healthcare (Istepanian and Pattichis 2006). Mobile health services (MHS), accordingly, can be described as a variety of health services (e.g., health consulting, hospital registering, and location-based services) delivered through the m-health platform (Ivatury et al. 2009). As a subset of e-health (Mechael 2009), m-health provides a personalized and interactive health services everywhere because of its advantages of mobility, portability, and ubiquity (Akter et al. 2010). Thus, m-health demonstrates an even stronger power than does traditional e-health in dealing with emergencies, fostering it to be widely developed across the world to deal with the healthcare problem for the elderly, especially in countries with serious aging tendencies, such as China (Woo et al. 2002).

In terms of the functions, m-health services can be classified into three types (Free et al. 2010): (1) the diagnostic services which are “designed to improve diagnosis, investigation, treatment, monitoring and management of disease” (Free et al. 2010, p. 251); (2) the preventive services which are designed for health promotion and treatment compliance; and (3) the procedural services which are designed to improve health care processes (e.g., appointment attendance). In terms of the users of m-health services, it can also be classified into four types: (1) m-health services for healthcare researchers (e.g., data collection); (2) m-health services for healthcare professionals (e.g., medical education and medical records); (3) m-health services for patients (e.g., appointment reminders and treatment programmes); and (4) m-health services for the general population (e.g., health behaviour change, first aid and emergency care) (Free et al. 2010). The m-health services examined in the current study belong to the preventive services used by the general population.

As m-health is a newly emerging phenomenon, empirical studies on these issues are still rare. Among the limited literature on this issue, Akter et al. (2010) view the adoption of m-health from the perspective of service quality and propose a three-dimensional measure of service quality (e.g., platform quality, interaction quality, and outcome quality). Another paper based on motivation theories and risk theories proposes that people’s intention to use mobile information and communication technology (ICT) for health promotion is determined by extrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation, and perceived risks (Cocosila and Archer 2010).

A further extension of the literature review can be traced to the research on e-health. As summarized by Yu et al. (2009), most studies on the adoption of e-health are based on TAM and are seen from the physicians’ or professionals’ point of view. To extend the theory to m-health, there are four research gaps to be filled. First, most previous studies are from the perspective of healthcare professionals rather than from that of end users or patients (Cocosila and Archer 2010). However, because healthcare professionals may stress on using m-health services to improve their productivity while the patients may use it for their own health promotion. This goal inconsistency may lead to different research models. This calls for the analysis from the patient’s perspective. Second, previous studies place much emphasis on the role of technology (e.g., TAM), paying less attention to the human side (Cocosila and Archer 2010). Just as suggested by prior studies, the technology acceptance may rely more on how human use the technology rather than the technology per se (Cocosila and Archer 2010). Thus, the human side of technology acceptance should be addressed. Third, previous studies are still dominated by the positive aspect of technology adoption (e.g., using e-health is beneficial), but studies viewing the dark side are rare (Bhattacherjee and Hikmet 2007). Thus previous model may not be adequate to explain the technology acceptance especially when the inhibitors play an important role. Finally, almost all previous studies are based on the general population, paying less attention to the unique features of specific populations. Thus, for certain particular population (e.g., elderly users), the context-specific explanations may not be available.

To fill these research gaps, this study attempts to provide an understanding of m-health from the general user centric view, focusing on the human side of m-health adoption and drawing up a dual factor (e.g., enablers and inhibitors) model of technology acceptance, particularly on the population of elderly users.

Characteristics of elderly users

There is a gap between theoretical analysis and practice in terms of the influence of ICT on older adults. The disequilibrium engagement and benefit from ICT for the older generation is known as a particular kind of “digital divide” (Hill et al. 2008). The elderly generally have less mobility and are more demanding in medical insurance, security, etc., and thus ICT could benefit them by providing convenient and comprehensive service (Tatnall and Lepa 2003). The benefits are summarized as “social and self-understanding benefits (e.g., increased access to current affairs and health information), interaction benefits (e.g., increased connectivity and social support), or task-orientated goals (e.g., ICT-assisted work, travel, shopping, and financial management)” (Selwyn 2004).

However, practical utility of ICT remains at a low level in the older generation. Numerous studies, especially qualitative studies, have been conducted to document and analyze the non-adoption or resistance usage. The barriers have been reported as: poor visual and motor ability negatively impacting the use of ICT, resistance to change brought about by new technology, potential culture influences, etc. (Hill et al. 2008; Selwyn 2004). Further external factors often faced by older adults regarding the use of ICT are: limited access to Internet technology through public libraries and community centres, capital costs, running costs, and maintenance (Tatnall and Lepa 2003).

This paper, as a preliminary study on the technology acceptance for a specific population, aims to gain an understanding of the roles of two unique features of elderly users in shaping their m-health adoption behaviour: technology anxiety and dispositional resistance to change. The first factor, technology anxiety, captures elderly users’ disposition to deal with new technology. According to previous literature, elderly users have higher technology anxiety than do younger users (Dyck et al. 1998; Laguna and Babcock 1997). The second factor, dispositional resistance to change, captures the elderly users’ disposition to deal with change. It reflects the pattern of how elderly users respond to the consequences induced by the usage of new technology. Elderly users have been found to have high propensity to resist changes (Oreg 2003, 2006). Because change in life style follows the usage of new technologies, their reaction to change will also influence their intention to adopt a new technology. Therefore, these two factors—one relevant to technology and the other related to personality—accurately reflect elderly users’ specialty when adopting m-health, and should thus be included in the research model.

Dual factor model of technology acceptance

The dual factor model of technology acceptance postulates that users’ intention to adopt a technology is influenced by both the enablers and the inhibitors (Cenfetelli 2004). The enablers refer to the factors which enhance usage when they are present, but at the same time, do not necessarily hurt usage when they are not available; in contrast, the inhibitors refer to the factors that hurt usage when they are present, but do not necessarily enhance usage when they are not available (Cenfetelli 2004). According to the dual factor model, the enablers and the inhibitors are respectively positively and negatively affect the technology adoption intention. Further, inhibitors not only directly influence technology adoption, but also indirectly influence technology adoption via enablers. The indirect effects are also seen as the biasing effects of inhibitors (Bhattacherjee and Hikmet 2007), i.e., when inhibitors are available, people tend to underestimate the value of enablers. Unlike the TAM which focuses on the positive aspect of technology, the dual factor model of technology acceptance sheds light on the dark side of technology acceptance as well (Bhattacherjee and Hikmet 2007).

Specifically, two TAM factors namely perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are treated as the enablers of the m-health service adoption because these two factors well capture the positive aspect of m-health service (Cocosila and Archer 2010; Or and Karsh 2009). When perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are present, users’ service adoption behaviour will be facilitated. Further, according to our preliminary interview, users’ resistance to change is the major barrier for their m-health service adoption behaviour, so it is taken as the inhibitor in our study. The role of resistance to change as an inhibitor can also be found in prior studies investigating the physicians’ e-health technology adoption behaviour (Bhattacherjee and Hikmet 2007; Nov and Schecter 2012). However, whether or not resistance to change still plays an important role in the general users’ e-health adoption behaviour has not been examined yet. In this study, we propose that resistance to change is also an inhibitor of m-health adoption behaviour because the general users may dislike to change their life styles. This becomes more salient for the elderly users.

Research model

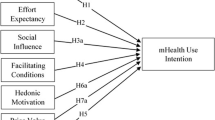

The research model can be depicted as in Fig. 1. The hypotheses can be separated into four groups. The first group (i.e., H1-3) is about the impacts of the enablers. The second group of hypotheses (i.e., H4-6) pays attention to the effects of the inhibitor. The third and fourth groups (i.e., H7-10) are about the antecedents of the enablers and the inhibitors.

The impacts of enablers

According to TAM, it is easy to argue the relationships between adoption intention, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use (Davis et al. 1989; Venkatesh and Morris 2003). In the present study, since mobile health services are a new emerging technology, its adoption intention should also be predicted by perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. These associations within the health services context are well supported by a plethora of empirical studies, as summarized by Yu et al. (2009). For example, Wilson and Lankton (2004) use TAM to investigate patients’ acceptance of provider-delivered e-health. Therefore, we propose:

-

H1:

Perceived usefulness is positively associated with intention to adopt mobile health services.

-

H2:

Perceived ease of use is positively associated with intention to adopt mobile health services.

-

H3:

Perceived ease of use is positively associated with perceived usefulness of mobile health services.

The impacts of inhibitors

The TAM factors, including perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, may reflect the enabling perceptions, while the inhibiting perceptions are not specifically identified in previous studies, even in the dual factor model (Bhattacherjee and Hikmet 2007). In a study discussing physicians’ usage of health information technology (HIT), Bhattacherjee and Hikmet (2007) propose that resistance to change well fits the definition of an inhibitor. Resistance can be featured as “a generalized opposition to change engendered by the expected adverse consequences of change” (Bhattacherjee and Hikmet 2007) (p. 727). Since adoption of mobile health services will induce changes in the ways in which people are used to dealing with health relevant issues, people have to give up their previous habits and reshape their health handling styles. Therefore, resistance to change as an opposing force to maintain a status quo (Lewin 1947) plays the role of inhibitor of adoption of mobile health services. Several previous studies from the physician’s or professional’s perspective have empirically confirmed the negative relationship between resistance to change and adoption intention (Bhattacherjee and Hikmet 2007; Spil et al. 2004). In this current study, we argue that this relationship is also applicable to patients who face a sufficiently high magnitude of change in life style. Thus, we suggest:

-

H4:

Resistance to change is negatively associated with intention to adopt mobile health services.

According to the dual factor model of technology usage, in addition to the direct effect of inhibitors on technology usage, inhibitors can also influence adoption intention indirectly via enablers as mediators (Cenfetelli 2004), suggesting that inhibitors can reduce enablers through the “biasing effect” (Bhattacherjee and Hikmet 2007). Bhattacherjee and Hikmet (2007) have proposed two mechanisms to explain the biasing effect: (1) negative perceptions can garner more cognitive attention than do positive perceptions, according to the norm theory (Kahneman and Miller 1986); and (2) inhibitors tend to anchor one’s overall perception, thus biasing those of the enablers. As to our study, when resistance to change is high, users tend to provide relatively low evaluations on usefulness and ease of use due to the biasing effect.

Specifically, when resistance to change is high, users will tend to consider that their habitual life style is good, thus the relative advantages of the m-health services which is based on the comparisons between the values of habitual life style and the new life style will be underestimated. Further, using new technology will involve uncertainty which will harm the evaluations on the new technology. This will become more salient for the users who have high level of resistance to change and are more sensitive to the uncertainty. Thus, giving relatively low evaluations on the usefulness of m-health services is a way to avoid using it (Oded Nov and Schecter 2012). So, we propose

-

H5:

Resistance to change is negatively associated with perceived usefulness of mobile health services.

The evaluation on the ease of use of the m-health service is relevant to users’ effort to learn and adapt to the new service. When users have high level of resistance to change, beyond the effort to master the skills to use m-health services, they need to spend more effort on overcoming negative cognitive and emotional responses to change (Oded Nov and Schecter 2012). In this case, the users with high level of resistance to change tend to overstate the difficulty to learn the m-health service and give relatively low evaluations on the ease of use. Thus, we propose

-

H6:

Resistance to change is negatively associated with perceived ease of use of mobile health services.

Technology anxiety

Technology anxiety, derived from the concept of computer anxiety, can be defined as “an individual’s apprehension, or even fear, when s/he is faced with the possibility of using computers [technology]” (Venkatesh 2000) (p. 349). According to the classical theories of anxiety, anxiety is considered inducing a negative impact on cognitive responses, particularly process expectancies (Phillips et al. 1972). Regarding perceived ease of use as a process expectancy in TAM (Venkatesh 2000), the negative relationship between technology anxiety and perceived ease of use is empirically confirmed in considerable prior studies, e.g., Venkatesh (2000) and Nov and Ye (2008). Within our research context, high technology anxiety can be featured as a distinct characteristic of elderly users (Dyck et al. 1998; Laguna and Babcock 1997). Thus, technology anxiety may play an important role in shaping elderly users’ perception of ease of use. We thus put forward:

-

H7:

Technology anxiety is negatively associated with perceived ease of use.

Further, technology anxiety also can lead to resistance to change because those with high technology anxiety tend to be more worried about the unexpected errors caused by technology (Durndell and Haag 2002). In this situation, they will try their best to maintain the status quo so as to avoid the serious consequences induced by incorrect operation of technology (Bhattacherjee and Hikmet 2007). Previous studies on technology acceptance have also suggested the linkage between technology anxiety and resistance to change (Harrington et al. 1990; Heinssen 1987; Joshi 1991). As to our research context, one major reason for elderly users to resist the mobile health services relay on their technology anxiety (Dyck et al. 1998; Laguna and Babcock 1997). Therefore:

-

H8:

Technology anxiety is positively associated with resistance to change.

Dispositional resistance to change

Differentiated from resistance to change, which is considered a situational factor depicting people’s perception about resistance to change, dispositional resistance to change is a personality factor from an individual difference perspective (Oreg 2003, 2006). By definition, people who have higher dispositional resistance to change are less likely to break away from routines, less likely to change their minds, and more likely to be emotionally stressed in the face of change (Nov and Ye 2008; Oreg 2003, 2006). Because the individuals with high dispositional resistance to change do not like to try out new things, but prefer to keep the stability of their life, the act of learning and using a new technology is psychologically difficult (Oreg 2003). In other words, regardless of how easy it is to use the technology they may still perceive low ease of use because they do not want to accept the changes. The negative relationship between dispositional resistance to change and perceived ease of use is also supported by prior studies, e.g., Nov and Ye (2008). Within our research context, since the elderly are regarded as a population with high dispositional resistance to change (Tuckman and Lorge 1953), the effect of dispositional resistance to change on perceived ease of use may be more salient. Thus:

-

H9:

Dispositional resistance to change is negatively associated with perceived ease of use of mobile health services.

Further, it is also easy to argue that, from the individual difference perspective, people with high dispositional resistance to change will be more likely to resist the changes induced by technology (Oreg 2003). This means that two dispositional factors—one relevant to technology (e.g., technology anxiety) and the other relevant to personality (e.g., dispositional resistance to change)—together predict people’s perception of resistance to change. Thus, our final hypothesis is that:

-

H10:

Dispositional resistance to change is positively associated with resistance to change.

Methodology

Research setting

To test our proposed research model and hypotheses, a field survey was conducted with the subjects who are the customers of a large company that provided m-health services targeting elderly consumers in Harbin, China. This company was one of the biggest companies in China providing integrated health services for elderly and it was also the only company providing home health care services for elderly that obtained the ISO9001 certification in China. These suggested that the target company was an appropriate site for data collection. As to the subjects, elderly consumers were selected as the target subjects because this consumer group accounted for a vast proportion of the whole consumers of health services.

The m-health services were initiated by the target company in collaboration with Harbin government and firstly released to the market in February 2010. The target consumers of these services were the older people of one million families in 500 communities in Harbin. The m-health services were built based on three main infrastructures: (1) a consulting and aiding platform including call centre, interactive voice responses (IVR) and information distribution and knowledge management modules; (2) a positioning platform that supported the real time positioning of the users via Global Positioning System (GPS) and Geographical Information System (GIS); and (3) a special service line that helped users to quickly access to the emergency aid services through mobile phones. Based on these infrastructures, the m-health services included two major types of service: (1) the emergency aid services that enabled the older people to press the SOS button of the customized mobile phone to access to the 24-h call centre which can further contact with their relatives and public service sectors; and (2) the information or consulting services that enabled the older people to obtain the information or professional suggestions about health promotion in daily life.

Measures

Measures for the constructs were adapted from previous studies with words changed to the research context (See Table 1). A seven-point Likert scale was used for all items. The measure for dependent variable adoption intention was adapted from Johnston and Warkentin (2010); the measures for TAM factors, including perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and resistance to change were adapted from Bhattacherjee and Hikmet (2007); the measure for technology anxiety was adapted from Thatcher and Perrewe (2002); and the measure for dispositional resistance to change was adapted from Oreg et al. (2008).

As the survey was conducted in China, the questionnaire was consequently translated to Chinese according to the translation committee approach (van de Vijver 2006; van de Vijver and Leung 1997). According to van de Vijver (2006), the committee approach for measurement translation is appropriate for linguistic equivalence and psychological equivalence through the sense-making process among committee members. Four native Chinese speakers; fluent in English were involved in the committee. All were IS Ph.D students. After introducing the purpose of the study and the definitions of the constructs, each student was requested to translate the items to Chinese individually. Afterwards, they were asked to discuss their translation results, item by item. Upon reaching an agreement on the translation, the Chinese version of the instrument was completed.

Data collection procedures

During June and July 2011, the target company helped to approach the potential consumers of the studied new mobile service from the customer list of existing services and collect the data through the community service centers. As the company was also engaged in other business targeting older people, it had good relationship with lots of community service centers. In the community service centers, the company provided training and interaction to its customers routinely about every 3 months. The training is mainly about the usage of the existing products and services and some are related to mobile services, e.g., how to type text message through the mobile. We requested the senior manager of the company to randomly distribute 250 questionnaires to the managers of its 12 service centers. These service centers were in charge of 372 communities among the whole 500, representing a wide range of the geographical (diversity) in Harbin. During the routine training and interaction, the company provided new product promotion when customers visited its service centers. For instance, the m-health services have also been shown to their customers. In the company, each employee in the service centers was in charge of a specific group of customers. The manager in the service center randomly asked the employees in the center to distribute the survey to his/her customers. Further, to encourage the participation, we also provided ten eggs as the incentives for participation because the older people always visited the service center when they went to the grocery shop, taking eggs as the incentives was consistent with their needs and could promote participation. Selecting this incentive method was also suggested by the executive manager of the target company who had rich experience in the elderly-relevant business and knew this population very well.

We believe this sampling and survey procedure is appropriate given the characteristics of the elderly who are not so easy to be accessed to compared to the ordinary people. In contrast, the employees in service centers had established good relationships with their customers during their long time cooperation and they easily explained the survey to their customers using their familiar communication methods. All of these ensure the success of the data collection.

Among the 250 distributed questionnaires, 204 valid responses were obtained with a response rate of 81.6 %. The high response rate was due to the good relationships between the employees in the service centers and the potential consumers. After removing the incomplete cases and outliers, female subjects occupy 46.1 %, and over 90 % of the subjects are over 40 years of age. The education level for 52.9 % of the subjects is high school or below; approximately 70 % of subjects have more than 2 years of mobile device usage experience (see Table 2). Since the selected sample targeted the elderly users of m-health services, certain demographic characteristics (such as gender and education) may be biased with the total population of China. However, certain demographic characteristics (e.g., gender) were similar with the overall population of China, suggesting its representativeness. However, even though this study did not use a randomized sample, the reported demographical data can be used as an evidence for cross-study comparison in the future.

Data analysis

Partial Least Squares (PLS) was used to test the research model because of the several advantages of this technique. First, as a second-generation structural equation modeling (SEM) technique, it can estimate the loadings (and weights) of indicators on constructs (hence, assessing construct validity) and the causal relationships among constructs in multistage models (Fornell and Bookstein 1982). Second, in comparison with covariance-based (CB) SEM, PLS is robust with fewer statistical identification issues; moreover it is most suitable for models with formative constructs and relatively small samples (Hair et al. 2011) which is the case in our study. Based on the above considerations, PLS was chosen for the current study.

The data analysis was conducted in two stages. At the first stage, the reliability and validity of the constructs, as well as the common method bias, were assessed to ensure the appropriateness of the measurement model. At the second stage, the structural model was assessed and hypotheses were tested (Hair et al. 1998).

Measurement model

Reliability was assessed by checking the composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) (Fornell and Larcker 1981; Hsu and Lin 2008). As shown in Table 3, the composite reliabilities for these constructs varied from 0.881 to 0.925 and average variance extracted ranged from 0.651 to 0.839, highly above the suggested cut-off values of 0.70 and 0.50, respectively (Fornell and Larcker 1981; Hsu and Lin 2008), suggesting very good construct reliability. The convergent validity could be assessed with the item loadings on the expected constructs (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Jiang et al. 2002). All item loadings were found to be significant and higher than 0.70, indicating good convergent validity of constructs.

The discriminant validity could be assessed by testing whether the square roots of AVEs were greater than the correlations (Fornell and Larcker 1981). As shown in Table 4, all correlations with the highest value of 0.546 were significantly lower than the square roots of AVEs, which were higher than 0.80, thus showing that the constructs had good discriminant validity.

Further, because our data was collected from a single source at the same time point, common method variance or bias might be a concern. We used the method suggested by Liang et al. (2007) to examine this issue. As shown in Table 5, the substantive factors explained 74.2 % of the variance, while the method factors explained only 1 % of the variance, indicating that common method variance was not a threat to the present study.

Structural model

The PLS results for the structural model are illustrated in Fig. 2. The results show that the relationships between perceived usefulness and adoption intention (β = 0.415, t = 5.919), perceived ease of use and adoption intention (β = 0.203, t = 2.523) and perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness (β = 0.462, t = 9.578) are significant, lending support to the hypotheses regarding the technology acceptance model (H1-3). The results also suggest that resistance to change has a significant impact on perceived usefulness (β = −0.312, t = 5.634) but insignificant effects on perceived ease of use (β = 0.074, t = 1.022) and adoption intention (β = −0.100, t = 1.409) and thus H5 is supported, while H4 and H6 are not. Further, technology anxiety and dispositional resistance to change are found to be negatively associated with perceived ease of use (β = −0.307, t = 4.305; β = −0.136, t = 2.052) but positively associated with resistance to change (β = 0.312, t = 4.250; β = 0.227, t = 3.193), lending support to H7-10.

Discussion

This research aims to investigate how the inhibitors (e.g., resistance to change) can influence adoption intention directly or indirectly via the enablers (e.g., perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use). Further, the roles of two antecedents of: resistance to change and perceived ease of use (technology anxiety and dispositional resistance to change) are examined. Three key findings can be derived from the current study.

Key findings

Three key findings can be derived from the current study. First, resistance to change (inhibitor) is found to significantly influence perceived usefulness, suggesting that when elderly users resist changes brought about by mobile health services, they will perceive these services as not useful. Thus, the inhibitors (e.g., resistance to change) can indirectly influence adoption intention via the enablers (e.g., perceived usefulness) (Cenfetelli 2004).

However, the impact of resistance to change on perceived ease of use is not significant. This is consistent with the results of Bhattacherjee and Hikmet (2007) which shows that the biasing effect of resistance to change on perceived usefulness is much stronger than that on perceived ease of use. One possible explanation is that the effort spent to overcome the negative cognitive and emotional responses to change (Oded Nov and Schecter 2012) is trivial compared to the effort to learn the technology, making the resistance to change be an insignificant source of the evaluations on ease of use.

The direct effect of resistance to change on adoption intention is also not supported. To better understand this insignificant effect, we also tested the mediation effect of perceived usefulness between resistance to change and adoption intention. According to Baron and Kenny’s (1986) method, when only resistance to change is considered, its effect on adoption intention is significant (β = –0.264, t = 3.844). In contrast, when the influence of perceived usefulness on adoption intention is considered, its effect becomes non-significant (β = −0.081, t = 1.193). Thus, the effect of resistance to change on adoption intention is fully mediated by perceived usefulness. This confirms the dual factor model which states that the impacts of the inhibitors on approach behaviour may be mediated by the enablers (Cenfetelli 2004).

Second, technology anxiety is found to be negatively associated with perceived ease of use, but positively associated with resistance to change, indicating that technology anxiety can reduce elderly users’ adoption intention by reducing perceived ease of use and increasing resistance to change.

Third, dispositional resistance to change is found to be negatively associated with perceived ease of use, but positively associated with resistance to change, similar to the role of technology anxiety, showing that it can suppress adoption intention by weakening perceived ease of use and strengthening resistance to change.

Limitations

Before discussing the theoretical and practical implications, the limitations of the present study need to be addressed. The first limitation of our study is that this study is from a human-centric perspective so the technology relevant characteristics such as the ubiquity, mobility and portability of the m-health services are not included in the research model. Although this model development is based on our research focus and the key factors found through the preliminary interview, lack of technology features in the model may affect the internal validity of the study. Thus, future studies can introduce these factors into the model, further investigate their impacts and compare their findings with ours. Further, prior studies on mobile services have also figured out that user mobility may play an important role in the mobile service adoption behaviour (Ghose and Han 2011), calling for empirical investigations on this factor in future research.

Second, this study used the convenience sampling method rather than the random sampling method to collect the data, thus the selection bias may be a problem. The convenience sampling approach was used because the target population—elderly users—are not so easy to be communicated as compared to the ordinary people. In contrast, we took the employees in service centers who had established good relationships with these target subjects as the agents to collect data can better remove their worries and ensure high response rate. When assigning the number of subjects in different service centers, we do try to make the ratio of subjects across different service centers be matched with the ratio of members across different service centers.

Finally, this study only adopted one special population (e.g., elderly users) and one special m-health service (e.g., preventive m-health service). This also limits the generalizability of our findings to other population or other types of m-health service. Therefore, future research can apply our proposed research model in other situations and compare their findings with ours, which may help to find potential moderators that define the application scope of our research model.

Implications for research

This study contributes to research in three aspects. First, this is one of the earliest studies empirically testing Cenfetelli’s (2004) dual factor model of IT usage in the m-health service context. The dual-factor model can shed light on both the bright side and the dark side of technology acceptance behaviour. Specifically, perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are identified as the enablers and the resistance to change is regarded as the inhibitor. When examining the effects of the enablers and the inhibitors, we find that the enablers can directly influence m-health service adoption intention while the impact of the inhibitor (e.g., resistance to change) on behavioural intention is fully mediated by perceived usefulness, confirming that the enablers have stronger power than the inhibitors when predicting approach behaviour compared to avoidance behaviour. Future research on technology acceptance should include the inhibitors as important predictors of behavioural intention by drawing upon the dual factor model and pay special attention to the mediating effects of enablers.

Second, we theorize and empirically validate that technology anxiety as a technology-related dispositional factor can influence the enablers and the inhibitors. By capturing the unique feature of elderly users in technology adoption, technology anxiety well reflects elderly users’ response to new technology. In particular, the study implies that technology anxiety can activate the inhibitors (e.g., resistance to change) and deactivate the enablers (e.g., perceived ease of use). This theorization also enriches the previous understanding of resistance to change and the dual factor model of technology acceptance.

Third, we separate the personality factor (e.g., dispositional resistance to change) and the status factor of resistance to change and empirically test their different roles. Dispositional resistance to change can influence resistance to change, but it is not the sole predictor of resistance to change. Technology anxiety which is a technical factor also can lead to resistance to change. Dispositional resistance to change can influence not only the resistance to change but also other factors such as perceived ease of use. Differentiating the personality factor from the status factor of resistance to change can help to highlight the different roles of these two factors in different research contexts.

Implications for practice

Several practical implications can be derived from the study. First, m-health service providers should pay attention to both the enablers and the inhibitors. As to the enablers, service providers should further improve their technology and service quality. As to the inhibitors, service providers should help users to make right evaluations on the technology and removing their biased evaluations. For example, service providers can list a table to compare the traditional life style and the the life style after using the m-health services to make users more easily catch the relative advantages of m-health services.

Second, mobile health service providers should provide good illustrations and training to the elderly users so as to reduce their technology anxiety. Marketers or providers could use multimedia to educate elderly users on how to use the technology and they could invite some elderly to demonstrate how to operate it.

Third, mobile health services providers should use progressive persuasion approach to gradually remove the elderly users’ resistance to change. For example, marketers could first impress upon the elderly that there will be no great changes required for them to make and that the mobile health services will simplify their lives. After this assurance, marketers could demonstrate how the mobile health services work.

Conclusion

Although mobile health services have become popular in the contemporary world, the empirical studies on this issue from the dark side especially as to elderly users are rarely conducted. The proposed research model provides some insights on how two dispositional factors (e.g., technology anxiety and dispositional resistance to change) can influence enablers (e.g., TAM factors) and inhibitors (e.g., resistance to change) of technology adoption. The findings show that beyond the technology-relevant factors, personal factors may also play an important role in the adoption of mobile health services. Our study also encourages future research on technology acceptance to pay attention to both enablers and inhibitors. For practitioners, they should engage in how to remove the barriers caused by certain dispositional factors so as to facilitate the diffusion of mobile health services.

References

Akter, S., D’ Ambra, J., & Ray, P. (2010). Service quality of mHealth platforms: development and validation of a hierarchical model using PLS. Electronic Markets, 20(3–4), 1–19.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bhattacherjee, A., & Hikmet, N. (2007). Physicians’ resistance toward healthcare information technology: a theoretical model and empirical test. European Journal of Information Systems, 16(6), 725–737.

Cenfetelli, R. T. (2004). Inhibitors and enablers as dual factor concepts in technology usage. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 5(11), 472–492.

Cocosila, M., & Archer, N. (2010). Adoption of mobile ict for health promotion: an empirical investigation. Electronic Markets, 20(3–4), 241–250.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003.

Durndell, A., & Haag, Z. (2002). Computer self efficacy, computer anxiety, attitudes towards the internet and reported experience with the internet, by gender, in an east european sample. Computers in Human Behavior, 18(5), 521–535.

Dyck, J. L., Gee, N. R., & Smither, J. A. (1998). The changing construct of computer anxiety for younger and older adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 14(1), 61–77.

Fornell, C., & Bookstein, F. L. (1982). Two structural equation models: lisrel and pls applied to consumer exit-voice theory. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 440–452.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Free, C., Phillips, G., Felix, L., Galli, L., Patel, V., & Edwards, P. (2010). The effectiveness of M-health technologies for improving health and health services: a systematic review protocol. BMC Research Notes, 3(10), 250–256.

Fukuoka, Y., Kamitani, E., Bonnet, K., & Lindgren, T. (2011). Real-time social support through a mobile virtual community to improve healthy behavior in overweight and sedentary adults: a focus group analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(3).

Ghose, A., & Han, S. (2011). An empirical analysis of user content generation and usage behavior on the mobile internet. Management Science, 57(9), 1671–1691.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. The Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152.

Harrington, K. V., McElroy, J. C., & Morrow, P. C. (1990). Computer anxiety and computer-based training: a laboratory experiment. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 6(3), 343–358.

Heinssen, R. K. (1987). Assessing computer anxiety: development and validation of the computer anxiety rating scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 3(1), 49–59.

Hill, R., Beynon-Davies, P., & Williams, M. D. (2008). Older people and internet engagement. Information Technology & People, 21(3), 244–266.

Hsu, C. L., & Lin, J. C. C. (2008). Acceptance of blog usage: the roles of technology acceptance, social influence and knowledge sharing motivation. Information & Management, 45(1), 65–74.

Istepanian, R. S. H., & Pattichis, C. S. (2006). M-health: emerging mobile health systems. New York: Springer.

Ivatury, G., Moore, J., & Bloch, A. (2009). A doctor in your pocket: health hotlines in developing countries. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 4(1), 119–153.

Jiang, J. J., Klein, G., & Carr, C. L. (2002). Measuring information system service quality: SERVQUAL from the other side. MIS Quarterly, 26(2), 145–166.

Johnston, A. C., & Warkentin, M. (2010). Fear appeals and information security behaviors: an empirical study. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 34(3), 549–566.

Joshi, K. (1991). A model of users’ perspective on change: the case of information systems technology implementation. Mis Quarterly, 15(2), 229–242.

Kahneman, D., & Miller, D. T. (1986). Norm theory: comparing reality to its alternatives. Psychological Review, 93(2), 136–153.

Laguna, K., & Babcock, R. L. (1997). Computer anxiety in young and older adults: implications for human–computer interactions in older populations. Computers in Human Behavior, 13(3), 317–326.

Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in group dynamics: I. concept, method, and reality in social sciences, social equilibria, and social change. Human Relations, 1(2), 5–41.

Liang, H., Saraf, N., Hu, Q., & Xue, Y. (2007). Assimilation of enterprise systems: the effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Quarterly, 31(1), 59–87.

Mechael, P. N. (2009). The case for mhealth in developing countries. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 4(1), 103–118.

Nov, O., & Schecter, W. (2012). Dispositional resistance to change and hospital physicians’ use of electronic medical records: a multidimensional perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(4), 648–656.

Nov, O., & Ye, C. (2008). Users’ personality and perceived ease of use of digital libraries: the case for resistance to change. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(5), 845–851.

Or, C. K. L., & Karsh, B.-T. (2009). A systematic review of patient acceptance of consumer health information technology. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association, 16(5), 550–560.

Oreg, S. (2003). Resistance to change: developing an individual differences measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 680–693.

Oreg, S. (2006). Personality, context, and resistance to organizational change. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(1), 73–101.

Oreg, S., Bayazit, M., Vakola, M., Arciniega, L., Armenakis, A., Barkauskiene, R., et al. (2008). Dispositional resistance to change: measurement equivalence and the link to personal values across 17 nations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 935–944.

Phillips, B. N., Martin, R. P., & Meyers, J. (Eds.). (1972). Interventions in relation to anxiety in school (Vol. 2). New York: Academic.

Selwyn, N. (2004). The information aged: a qualitative study of older adults’ use of information and communications technology. Journal of Aging Studies, 18, 369–384.

Spil, T. A. M., Schuring, R. W., & Michel-Verkerke, M. B. (2004). Electronic prescription system: do the professionals use it? International Journal of Healthcare Technology and Management, 6(1), 32–55.

Tatnall, A., & Lepa, J. (2003). The internet, e-commerce and older people: an actor-network approach to researching reasons for adoption and use. Logistics Information Management, 16(1), 56–63.

Thatcher, J. B., & Perrewe, P. L. (2002). An empirical examination of individual traits as antecedents to computer anxiety and computer self-efficacy. Mis Quarterly, 26(4), 381–396.

Tuckman, J., & Lorge, I. (1953). Attitudes toward old people. Journal of Social Psychology, 37, 249–260.

van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2006). Conducting cross-cultural research. Paper presented at the 2006 Regional Conference of Academy of Management Research Method Division, Hong Kong SAR.

van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Leung, K. (1997). Methods and data-analysis for cross-cultural research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Venkatesh, V. (2000). Determinants of perceived ease of use: integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model. Information Systems Research, 11(4), 342–365.

Venkatesh, V., & Morris, M. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478.

Wilson, E. V., & Lankton, N. K. (2004). Modeling patients’ acceptance of provider-delivered e-health. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 11(4), 241–248.

Woo, J., Kwok, T., Sze, F., & Yuan, H. (2002). Ageing in China: health and social consequences and responses. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(4), 772–775.

Yu, P., Li, H., & Gagnon, M. P. (2009). Health IT acceptance factors in long-term care facilities: a cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 78(4), 219–229.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by the Hong Kong Scholars Program and the National Science Foundation of China Grant (71201118, 71101037, 71201058), Self-dependent Research Project for Social and Humanity Science of Wuhan University (274130), and Wuhan University Academic Development Plan for Scholars after 1970s (“Research on Network User Behavior”).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Doug Vogel

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, X., Sun, Y., Wang, N. et al. The dark side of elderly acceptance of preventive mobile health services in China. Electron Markets 23, 49–61 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-012-0112-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-012-0112-4