Abstract

It is thought that among children at a high risk for antisocial personality disorder, the level of individual anxiety might constitute an important marker with respect to symptomatology and prognosis. The aim of the present study was to examine whether associations between anxiety and subtypes of aggression (proactive and reactive) exist in boys with early-onset subtype of conduct disorder (CD) and co-morbid attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A detailed psychometric characterization of boys with ADHD and the early-onset subtype of CD (n = 33) compared to healthy controls (n = 33) was performed. The assessment included trait anxiety, internalizing and externalizing problems, symptoms of psychopathy and temperament traits, as well as subtypes of aggressive behavior. Descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and group comparisons were calculated. The clinical group was characterized by higher levels of externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Individual anxiety was positively associated with harm avoidance, symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and by trend with reactive aggression. In contrast, boys with reduced levels of anxiety exhibited more callous-unemotional traits. Our results indicate that children with the early-onset subtype of CD and ADHD constitute a psychopathological heterogeneous group. The associations between individual levels of trait anxiety, temperament traits, and subtypes of aggressive behavior in children with ADHD and severe antisocial behavior emphasize the impact of anxiety as a potential key factor that might also be crucial for improvement in therapeutic strategies and outcome measures. Anxiety should be considered carefully in children with ADHD and the early-onset subtype of CD in order to optimize current therapeutic interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children with severe antisocial behavior constitute a heterogeneous group with respect to clinical symptomatology, severity as well as the persistence of aggressive behavior and treatment response (Frick and Marsee 2006; Lahey et al. 2005; Simonoff et al. 2004). While some of these children show mild and temporal-limited forms of antisocial behaviors, others are characterized by increasingly severe antisocial development (for a review, see Herpertz-Dahlmann et al. 2007). Longitudinal studies indicate that these children typically show the early-onset subtype of CD, are frequently comorbid for ADHD, and at a high risk for the development of an antisocial personality disorder (ASPD; Moffitt et al. 2002, for a review, see Vloet et al. 2006). However, although these children represent a well-defined subgroup, their developmental pathways differ significantly (Simonoff et al. 2004; Moffitt et al. 2002). Whereas aggressive behavior constitutes a core symptom in these children, subtypes of aggressive behavior differ significantly within this population (for a review, see Kempes et al. 2005). A widely accepted differentiation of aggressive behavior in this context is the distinction between impulsive aggression (which is typically explosive, uncontrolled and accompanied by high levels of arousal and emotions such as fear; this form is known as reactive or affective aggression) and goal-oriented aggression (which is generally accompanied by low arousal; this is known as proactive or instrumental aggression; Berkowitz 1993). Although aggressive behavior is an important clinical problem that is commonly found in clinical samples, few studies have investigated these subtypes of aggressive behavior in children with severe antisocial behavior (Dodge et al. 1997; Connor et al. 2003, 2004). While two recent studies found positive associations between ADHD symptomatology and reactive aggression, there are no studies that have investigated the association between aggressive subtypes and anxiety in clinically referred children at high risk for antisocial development, i.e., those with early-onset subtype of CD and co-morbid for ADHD.

Corresponding to children with antisocial behavior, individuals with ASPD, which can be diagnosed according to a well-defined symptomatology, still represent a diverse population, differing e.g. with respect to psychopathology, frequency of delinquent behavior, and types of violent acts. It has been speculated that the levels of individual anxiety within a group of subjects with ASPD might constitute an important differential criterion (Coid and Ullrich 2010) that might also be associated with different forms of aggressive behavior and diverse personality traits (for a review, see De Brito and Hodgins 2009). In this context, data from epidemiological investigations into large community samples have confirmed that about one-half of individuals with ASPD also experience comorbid anxiety disorders, while the other half reports normal to low levels of anxiety (Sareen et al. 2004; Lenzenweger et al. 2007; Hodgins et al. in press).

Although the existence of internalizing disorders in children with a high risk for antisocial behavior was already described many years ago (for a review, see Olsson 2009), recent work has increasingly emphasized the impact of individual anxiety on symptomatology and outcome (Connor et al. 2010, for a review, see Vloet et al. 2010). The paucity of results in this field might stem from the counter-intuitive nature of the relationship between anxiety and antisocial behavior. Many psychophysiological studies have shown that low levels of anxiety are closely connected to antisocial, aggressive, or delinquent behavior (for a review, see Scarpa and Raine 2004; Herpertz et al. 2001, 2005), and low levels of anxiety are associated with an increased risk for ongoing antisocial behavior (Loney et al. 2006; Herpertz et al. 2003; Moffitt et al. 2002). Furthermore, there is growing evidence that low anxiety in some children is closely connected with callous-unemotional traits that are observed in children with a particularly severe, aggressive, and stable pattern of antisocial behavior (for a review, see Frick 2009).

However, in community samples, about 25–33% of all children with CD are comorbid for anxiety disorders (Ford et al. 2003; Marmorstein 2007). Clinical samples indicate rates that vary from 4 to 48% (Masi et al. 2008; for meta-analyses, see Angold et al. 1999; for a review, see Olsson 2009).

The impact of comorbid anxiety on the symptomatology and the development of children with severe antisocial behavior is still unclear. Data indicate that comorbid anxiety disorders might prevent children with CD/ADHD from further antisocial development (Gregory et al. 2007; Washburn et al. 2007), and it has been speculated that inhibition (which is closely associated with anxiety disorders) might especially constitute a protective factor against the development of delinquency (Kerr et al. 1997; for a review, see Degnan and Fox 2007). In contrast, other studies have found a negative impact of anxiety on antisocial development in children, indicating that anxiety is a risk factor for aggressiveness and delinquency (Walker et al. 1991; Sourander et al. 2007).

It is possible that these contradictory findings might be disentangled by a more detailed phenotyping of the affected children. Hence, one aim of the current study is to assess externalizing as well as internalizing symptoms in children with severe antisocial behavior. Especially, trait anxiety (for a review, see Hodgins et al. 2009) and various forms of aggressive behavior (Raine et al. 2006, for a review, see Kempes et al. 2005) as well as associated temperament traits (Frick and Hare 2001, for a review see Vloet et al. 2010) have been considered. In this context, it has been argued that especially differences in harm avoidance (Schmeck and Poustka 2001), novelty seeking (Frick et al. 2003), and the occurrence of callous-unemotional traits seem to be important risk factors, which might even have predictive power for a negative development (for a review, see Lynam and Gudonis 2005).

Much information remains to be learned about these children. First, are individual levels of anxiety positively associated with reactive aggression and harm avoidance in children with severe antisocial behavior? This may be expected based on the theoretical model of reactive aggression and previous findings in community samples (Marsee and Weems 2008; for a review, see Degnan and Fox 2007). Second, what traits are observed in children who have reduced levels of anxiety? Specifically, is their aggressive behavior predominantly proactive, and do they have callous-unemotional traits (for a review, see Frick 2009)? Based on previous findings, we expect participants with reduced levels of anxiety to engage more frequently in proactive aggression and show more callous-unemotional traits.

In order to address these questions, we conducted a psychometric assessment in children and adolescents with early-onset CD and in healthy controls. Both groups were assessed for their levels of anxiety using self-rated and parent-rated instruments. Furthermore, we assessed character and personality traits, the type of aggression, and the level of callous-unemotional traits. The level of psychopathology regarding CD and ADHD was rated by parents. We also determined IQ and psychiatric diagnoses.

Methods

Participants

A total of 33 boys with the early-onset subtype of CD and ADHD, mean age 11.2 years (age range: 7.4–15.6 years, SD: 2.2 years) participated in the study. Since in girls the prevalence of severe conduct disorder in this age range is low (Lahey et al. 1999), girls were not included in the study. All subjects fulfilled diagnostic criteria for the early-onset subtype of CD and comorbid ADHD according to DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association 1994) and had been consecutively admitted to the in- or outpatient clinics of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the University Hospital Aachen. Thirty-three boys were in a healthy control (HC) group with matching age (for details, see Table 1). Children in the HC group were recruited by a broad announcement at the local schools that made no reference to the aim of the study. All subjects were assessed for intelligence using the WISC IV assessment battery (German: HAWIK-IV, Petermann and Petermann 2007). Both groups were comparable with respect to age (t = 1.2, P = 0.22) but differed regarding IQ (t = 3.0; P < 0.05); this is a well-known observation in the literature when comparing these kind of samples. According to the criteria of DSM-IV-TR, co-morbidity with ADHD was diagnosed as subtypes of combined or predominantly hyperactive/impulsive ADHD in the majority of patients (DSM-IV 314.01; 87,8%) and of predominantly inattentive subtype (DSM-IV 314.00) in 12,2% of subjects. In the clinical group, eleven boys (33%) showed further comorbid disorders, the majority of which being internalizing and elimination disorders. For details, see Table 1.

Psychometric assessment

All participants underwent an extensive child psychiatric examination conducted by an experienced child and adolescent psychiatrist. The severity of ADHD and CD symptoms was assessed by means of the German Parental and Teacher Report on ADHD symptoms (FBB-HKS, “Fremdbeurteilungsbogen Hyperkinetische Störung”) and on CD symptoms (FBB-SSV, “Fremdbeurteilungsbogen Störung des Sozialverhaltens”), which is part of the Diagnostic System of Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents (DISYPS-KJ, Döpfner and Lehmkuhl 1998). It is commonly used in Germany to assess ADHD symptomatology and it has a favorable internal consistency and retest reliability (Breuer et al. 2009). The FBB-HKS includes all of the items that are given in the diagnostic categories of the ADHD subtypes described by DSM-IV. It not only determines the number of criteria that have been fulfilled but also provides severity scores for each item that ranges from 0 to 3. The FBB-HKS contains the subscales “Inattention” (9 Items; diagnostic cutoff six items scored two or three), “Hyperactivity” (6 items; diagnostic cutoff three items scored two or three), and “Impulsivity (5 items; diagnostic cutoff one item scored two or three). The FBB-SSV consists of the subscales “Oppositional Defiant Symptoms” (8 items) and “Conduct Symptoms” (15 items); diagnostic cutoffs for each scale are 3 items scored two or three.

Additionally, the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL, Achenbach 1991) was assessed in all participants. It is a clinical standard instrument to assess a child’s problem behaviors and social competency from parents or other close relatives within the past 6 months. It contains a list of 118 items that are rated by the parents on a three-point likert scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, 2 = very true or often true). The CBCL/4-18 scoring profile provides raw scores, T scores, and percentiles for eight different cross-informant syndromes (aggressive behavior, anxious/depressed problems, attention problems, delinquent behavior, social problems, somatic complaints, thought problems, and withdrawal). Selected subscales are summarized within scores for internalizing, externalizing, and total problems.

An additional instrument was (1) the Antisocial Personality Screening Device (APSD, Frick and Hare 2001), a 20-item rating scale that assesses callous-unemotional traits, narcissism, and impulsivity. Parent ratings were used only, and T scores were calculated based on norms of a North American population provided with the manual. (2) The “Reactive-Proactive Aggression Questionnaire” (RPQ) is a self-reported measure of aggression subtype that distinguishes between predominantly reactive and proactive aggression over 23 items (Raine et al. 2006). Raw values’ sum scores of the subscales “reactive aggression” (12 Items, range 0–2) and “proactive aggression” (13 items, range 0–2) were entered into analyses. Based on a North American population, raw values greater than one standard deviation are 11.1 for reactive aggression and 3.4 for proactive aggression (Baker et al. 2008). A pure proactive subtype is defined as showing values exceeding one SD on the subscale “proactive aggression”, while values on the subscale “reactive aggression” are within one SD. Opposed is the pure reactive subtype defined according to the above with only reactive aggression exceeding one SD and the mixed type showing values on both the proactive and the reactive subscale exceeding one SD. (3) The “State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children” (STAIC, Laux et al. 1981) measures state and trait anxiety of children and is a widely used instrument for self-reported anxiety. In this study, trait anxiety was assessed only. The questionnaire comprises 20 items scored on a 3-point likert-scale (range 0–2). Raw sum scores were calculated and entered into analyses. (4) The “Junior Temperament and Character Inventory” (JTCI, Schmeck et al. 2001) comprises a personality inventory deduced from Cloninger’s psychobiological theory of personality and consists of seven subscales: novelty seeking; harm avoidance; reward dependence; self-directedness; cooperativeness; and self-transcendence. It was designed for the use of adolescents aged 12–18, though authors state, that the use starting from ten years yields valid results. In our sample, children aged 10 years and above were asked to complete the JTCI, data from 19 children were collected. Based on our hypotheses, solely the subscales “Harm avoidance” and “Novelty seeking” were analyzed.

Psychiatric classification according to DSM-IV-TR was based on the K_SADS-PL (Kaufman et al. 1997; German version by Delmo et al. 2001), as well as a developmental history, playroom observation, and an extensive neuropediatric examination. All HCs underwent the same diagnostic assessment to rule out any psychiatric disorder.

Participants were excluded from the study if they had an overall IQ below 80, evidence of a neurological disorder or a past or current diagnosis of psychosis, mania, substance abuse, pervasive developmental disorder, or a receptive language disorder.

The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles for the medical community regarding human investigation (the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki). All subjects and their parents gave their written informed consent, after receiving a comprehensive description of the study protocol.

Data analysis and statistical tests

Data analysis was performed with the IBM SPSS Version 18 software package (IBM SPSS, Chicago). Demographic and clinical data were evaluated using descriptive statistics. Comparisons of the psychometric assessments were made between the subjects and the HCs by means of ANCOVAs with IQ as a covariate. Pearson’s correlations were calculated in the CD/ADHD-group between anxiety, selected character traits, and the types of aggressive behavior. Group comparisons were calculated for subjects in the clinical group low (below 25th percentile) or high (above 75th percentile) in trait anxiety by means of Mann–Whitney-U test. Effect sizes were calculated from z-scores.

Results

Differences in the ADHD and CD symptom severity scores in the clinical sample compared to the HC group (for details, see Table 2) were significant with elevated measures in the following scales: inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity as indicated by parent ratings (FBB HKS), CD symptomatology, reactive aggressive behavior, proactive aggressive behavior, callous-unemotional traits, narcissism, and impulsivity. The patients with CD assessed themselves to be significantly more anxious than did the HCs on the anxiety inventory (STAIC). The parents of subjects with CD/ADHD rated internalizing and anxious-depressive behavior of their children higher than did the parents of the HC children. Children in the clinical group showed elevated “Novelty seeking” but equaled children in the HC group with regard to harm avoidance.

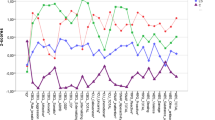

When investigating correlates of trait anxiety of children in the clinical group, associations were detected with symptoms of the oppositional defiant disorder as well as with harm avoidance. By trend, a correlation with reactive aggression was found with medium effect sizes. Anxious and depressive behavior, as rated by parents in the CBCL, was associated with symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder negatively related to callous-unemotional traits. Marginally significant (P = 0.06) were a positive correlation with reactive aggression. Correlations within the HC group showed significant positive associations between trait anxiety and harm avoidance only (r = 0.48; P = 0.01).

Comparisons of patients low (n = 8) versus high (n = 9) in trait anxiety yielded differences with regard to harm avoidance, reactive aggression, and symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder; all of them were being elevated in the high anxiety group with large effect sizes. Post hoc linear regression analyses were calculated for trait anxiety. Harm avoidance and oppositional defiant symptoms were entered as factors in the model (n = 19) with R 2 = 0.55; F = 9.8, P = 0.002 and β-weights: Harm avoidance β = 0.42; P = 0.033 and ODD β = 0.45, P = 0.026. Further post hoc correlations were calculated for the relationship of harm avoidance and (1) ODD-Symptoms: r = 0.44; P = 0.06 (2) CD symptoms r = 0.21; P = 0.37. Reactive aggression was associated with (1) impulsivity as measured by FBB-HKS with r = 0.56; P = 0.01 and with (2) harm avoidance: r = 0.45; P = 0.07 (Table 3).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to perform a detailed psychometric characterization of children with the early-onset subtype of CD and ADHD. The clinical sample was characterized by significantly higher levels of anxiety, aggressive behavior, and callous-unemotional traits than in HC. According to our first hypothesis, trait anxiety was positively associated with harm avoidance in the clinical group. Given that this association was also found in HC, we would speculate that trait anxiety and the temperament scale harm avoidance show a high conceptual overlap. Harm avoidance contains the subscales anticipatory worry, fear of uncertainty, shyness, and fatigability that are closely related to emotions known in anxiety.

We further found a positive association between reactive aggressive behavior and trait anxiety as well as parent-rated anxiety on a marginally significant level, while no interrelation with proactive aggression was found. This is in agreement with former data, indicating that reactive aggressive behavior is more closely associated with anxiety symptoms than is proactive aggressive behavior (Dodge et al. 1997; Vitaro et al. 2002). More recently, Marsee and Weems (2008) found gender-associated differences indicating that boys with high levels of anxiety were especially characterized by high levels of reactive aggression. Of note, in our sample, reactive aggression was also associated with harm avoidance, strengthening the connection between reactive aggression and anxiety-related traits. Both anxiety and reactive aggression have similar correlates, such as autonomic hyper arousal (Scarpa and Raine 2004; Fowles 2000). Correspondingly, data from an epidemiological investigation indicate a positive association between reactive aggressive behavior and increased skin conductance reactivity (Hubbard et al. 2002). Given that former studies investigated community samples, the results of the present study indicate for the first time (to our knowledge) that this association also exists in hospitalized children with the early-onset subtype of CD and ADHD. Bubier and Drabick (2009) proposed a model of the etiology of reactive aggression in which anxious children are predisposed to experience negative emotions more frequently and exhibit an impulsive response style that might become automatic over time. Our results support this hypothesis as reactive aggression was highly correlated with impulsivity.

Anxiety was predominantly associated with oppositional defiant disorder but not with symptoms of core conduct behavior. The relationship between anxiety and oppositional behavior has already been found in other clinical samples with up to 40% of patients with ODD showing clinical apparent anxiety (Garland and Garland 2001; Rettew et al. 2004). Furthermore, it has been speculated that “harm avoidance”, which is a core feature of anxiety disorders, is more consistently related to ODD than to CD (Drabick et al. 2008). Our data confirm this hypothesis, though based on a small case number.

Our second assumption, that children with both CD and reduced levels of anxiety would be characterized by proactive aggressive behavior and callous-unemotional traits, was partially confirmed. While we found no significant correlations between reduced levels of individual anxiety and proactive aggressive behavior, the analyses of parent-reported anxiety revealed that children with lower levels of anxiety exhibited more callous-unemotional traits. Recent longitudinal data have indicated that callous-unemotional traits are a strong predictor of future antisocial behavior and constitute an important risk factor for a negative outcome (for a review, see Lynam and Gudonis 2005). Hence, our results might indicate that reduced levels of anxiety are associated with risk factors for further antisocial development.

Our negative results with respect to the association between proactive aggressive behavior and low levels of anxiety might be explained by methodological shortcomings. One the one hand, the amount of anxiety was overall higher in the clinical population than in healthy controls, indicating that the number of patients with low or non-existent anxiety was rather small. Of note, the sum score in the low anxiety subgroup was still higher than mean sum scores of trait anxiety in HC. On the other hand, it is known that proactive aggression—especially when not accompanied by reactive aggression—is rare in children. Previous studies that assessed proactive aggressive behavior in children and adolescents investigated larger community samples and could reveal a small proportion of pure proactive aggression (Connor et al. 2004). To further investigate the association between proactive aggressive behavior and anxiety in clinical samples with the early-onset subtype of CD, studies with larger sample sizes will likely be necessary (Pliszka 2009).

Conclusions

Taken together, our data indicate that in comparison with HC children, boys with the early-onset subtype of CD and ADHD differ regarding both certain personality traits (anxiety, novelty seeking, psychopathic traits) and the subtypes of aggressive behavior and that anxiety represents an important and easy means to differentiate within the group. One subgroup with the early-onset type of CD is more harm-avoidant, exhibits more reactive aggression, and engages more frequently in ODD behavior. Another subgroup shows less anxiety, but more callous-unemotional traits. With respect to therapy, these different psychopathological profiles should be taken into account as children with higher levels of anxiety and frequent oppositional behavior might benefit from cognitive behavioral therapies and parent management training (Kazdin and Whitley 2006; for a review, see Vloet et al. 2010). Future research is warranted with regard to the evaluation of treatment strategies for patients high in anxiety as opposed to those low in anxiety but elevated in psychopathic traits.

Limitations

Some limitations of our study need to be considered. First, the sample size was quite small and conclusions should be drawn with care. Second, because of the dominance of antisocial behavior in males compared to females, we started with the investigation into boys with CD. A detailed psychometric characterization of girls with CD should be performed in the future. Third, HCs differed from the clinical group with regard to IQ. Group comparisons were controlled for this potentially confounding factor; still, the influence is mathematically not eliminated completely and results should be interpreted with care.

References

Achenbach TM (1991) Childbehavior checklist—deutsche version. Hogreve, Göttingen

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC

Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A (1999) Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(1):57–87

Baker LA, Raine A, Liu J, Jacobson KC (2008) Differential genetic and environmental influences of reactive and proactive aggression in children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 36(8):1265–1278. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9249-1

Berkowitz L (1993) Aggression: its causes, consequences and control. Temple University Press, Philadelphia

Breuer D, Wolff Metternich T, Dopfner M (2009) The assessment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) by teacher ratings—validity and reliability of the fbb-hks. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother 37(5):431–440. doi:kij_37_5_431[pii]10.1024/1422-4917.37.5.431

Bubier JL, Drabick DA (2009) Co-occurring anxiety and disruptive behavior disorders: the roles of anxious symptoms, reactive aggression, and shared risk processes. Clin Psychol Rev 29(7):658–669. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.005-S0272-7358(09)00110-X

Coid J, Ullrich S (2010) Antisocial personality disorder and anxiety disorder: a diagnostic variant? J Anxiety Disord 24(5):452–460. doi:S0887-6185(10)00048-4[pii]10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.001

Connor DF, Steingard RJ, Anderson JJ, Melloni RH Jr (2003) Gender differences in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 33(4):279–294

Connor DF, Steingard RJ, Cunningham JA, Anderson JJ, Melloni RH Jr (2004) Proactive and reactive aggression in referred children and adolescents. Am J Orthopsychiatry 74(2):129–136. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.74.2.1292004-13484-005[pii]

Connor DF, Chartier KG, Preen EC, Kaplan RF (2010) Impulsive aggression in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: symptom severity, co-morbidity, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder subtype. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 20(2):119–126. doi:10.1089/cap.2009.0076

De Brito SA, Hodgins S (2009) Antisocial personality disorder. In: McMurran M, Howard R (eds) Personality, personality disorder, and violence: an evidence based approach. Wiley, Chichester, pp 133–153

Degnan KA, Fox NA (2007) Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: multiple levels of a resilience process. Dev Psychopathol 19(3):729–746. doi:S0954579407000363[pii]10.1017/S0954579407000363

Delmo C, Welffenbach O, Gabriel M, Stadler C, Poustka F (2001) Diagnostisches interview kiddie-sads present and lifetime version (k-sad-pl). Frankfurt

Dodge KA, Lochman JE, Harnish JD, Bates JE, Pettit GS (1997) Reactive and proactive aggression in school children and psychiatrically impaired chronically assaultive youth. J Abnorm Psychol 106(1):37–51

Döpfner M, Lehmkuhl G (1998) Diagnostik-system für psychische störungen im kindes- und jugendalter nach icd-10 und dsm-iv. Huber, Bern

Drabick DA, Gadow KD, Loney J (2008) Co-occurring odd and gad symptom groups: source-specific syndromes and cross-informant comorbidity. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 37(2):314–326. doi:793017614[pii]10.1080/15374410801955862

Ford T, Goodman R, Meltzer H (2003) The british child and adolescent mental health survey 1999: the prevalence of dsm-iv disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42(10):1203–1211. doi:10.1097/00004583-200310000-00011S0890-8567(09)61983-3[pii]

Fowles DC (2000) Electrodermal hyporeactivity and antisocial behavior: Does anxiety mediate the relationship? J Affect Disord 61(3):177–189

Frick PJ (2009) Extending the construct of psychopathy to youth: Implications for understanding, diagnosing, and treating antisocial children and adolescents. Can J Psychiatry 54(12):803–812

Frick PJ, Hare R (2001) The antisocial process screening device (apsd). Multi-Health Systems, Berkshire

Frick PJ, Marsee MA (2006) Psychopathy and developmental pathways to antisocial behavior in youth. In: Patrick C (ed) Handbook of psychopathy. Guilford Press, New York, pp 353–374

Frick PJ, Cornell AH, Barry CT, Bodin SD, Dane HE (2003) Callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems in the prediction of conduct problem severity, aggression, and self-report of delinquency. J Abnorm Child Psychol 31(4):457–470

Garland EJ, Garland OM (2001) Correlation between anxiety and oppositionality in a children’s mood and anxiety disorder clinic. Can J Psychiatry 46(10):953–958

Gregory AM, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Koenen K, Eley TC, Poulton R (2007) Juvenile mental health histories of adults with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry 164(2):301–308. doi:164/2/301[pii]10.1176/appi.ajp.164.2.301

Herpertz SC, Wenning B, Mueller B, Qunaibi M, Sass H, Herpertz-Dahlmann B (2001) Psychophysiological responses in ADHD boys with and without conduct disorder: implications for adult antisocial behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40(10):1222–1230. doi:10.1097/00004583-200110000-00017

Herpertz SC, Mueller B, Wenning B, Qunaibi M, Lichterfeld C, Herpertz-Dahlmann B (2003) Autonomic responses in boys with externalizing disorders. J Neural Transm 110(10):1181–1195. doi:10.1007/s00702-003-0026-6

Herpertz SC, Mueller B, Qunaibi M, Lichterfeld C, Konrad K, Herpertz-Dahlmann B (2005) Response to emotional stimuli in boys with conduct disorder. Am J Psychiatry 162(6):1100–1107. doi:162/6/1100[pii]0.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1100

Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Konrad K, Herpertz S (2007) The role of ADHD in the etiology and outcome of antisocial behavior and psychopathy. In: Felthous A, Saß H (eds) International handbook on psychopathic disorders and the law, vol 1. Willey, England, pp 199–216

Hodgins S, de Brito S, Simonoff E, Vloet T, Viding E (2009) Getting the phenotypes right: an essential ingredient for understanding aetiological mechanisms underlying persistent violence and developing effective treatments. Front Behav Neurosci 3:44. doi:10.3389/neuro.08.044.2009

Hodgins S, De Brito S, Chhabra P, Cote G (in press) Anxiety disorders among offenders with antisocial personality disorders: a distinct subtype? Can J Psychiatry

Hubbard JA, Smithmyer CM, Ramsden SR, Parker EH, Flanagan KD, Dearing KF, Relyea N, Simons RF (2002) Observational, physiological, and self-report measures of children’s anger: relations to reactive versus proactive aggression. Child Dev 73(4):1101–1118

Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N (1997) Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-pl): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(7):980–988. doi:S0890-8567(09)62555-7[pii]10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021

Kazdin AE, Whitley MK (2006) Comorbidity, case complexity, and effects of evidence-based treatment for children referred for disruptive behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol 74(3):455–467. doi:2006-08433-006[pii]10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.455

Kempes M, Matthys W, de Vries H, van Engeland H (2005) Reactive and proactive aggression in children–a review of theory, findings and the relevance for child and adolescent psychiatry. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 14(1):11–19. doi:10.1007/s00787-005-0432-4

Kerr M, Tremblay RE, Pagani L, Vitaro F (1997) Boys’ behavioral inhibition and the risk of later delinquency. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54(9):809–816

Lahey BB, Miller TL, Gordon RA, Riley AQ (1999) Developmental epidemiology of the disruptive behavior disorders. In: Quay HC, Hogan AE (eds) Handbook of disruptive behavior disorders in childhood and adolescence. Kluwer, New York, pp 449–477

Lahey BB, Loeber R, Burke JD, Applegate B (2005) Predicting future antisocial personality disorder in males from a clinical assessment in childhood. J Consult Clin Psychol 73(3):389–399. doi:2005-06517-002[pii]10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.389

Laux L, Glanzmann P, Schaffner P, Speilberger C (1981) Das state-trait-angstinventar (stai). Hogreve, Göttingen

Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC (2007) Dsm-iv personality disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry 62(6):553–564. doi:S0006-3223(06)01192-9[pii]10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019

Loney BR, Lima EN, Butler MA (2006) Trait affectivity and non-referred adolescent conduct problems. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 35(2):329–336. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_17

Lynam DR, Gudonis L (2005) The development of psychopathy. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 1:381–407. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144019

Marmorstein NR (2007) Relationships between anxiety and externalizing disorders in youth: the influences of age and gender. J Anxiety Disord 21(3):420–432. doi:S0887-6185(06)00097-1[pii]10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.06.004

Marsee MA, Weems CF (2008) Exploring the association between aggression and anxiety in youth: a look at aggressive subtypes, gender and social cognition. J Child Fam Stud 17:154–168

Masi G, Milone A, Manfredi A, Pari C, Paziente A, Millepiedi S (2008) Conduct disorder in referred children and adolescents: clinical and therapeutic issues. Compr Psychiatry 49(2):146–153. doi:S0010-440X(07)00120-4[pii]10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.08.009

Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne BJ (2002) Males on the life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways: follow-up at age 26 years. Dev Psychopathol 14(1):179–207

Olsson M (2009) Dsm diagnosis of conduct disorder (cd)—a review. Nord J Psychiatry 63(2):102–112. doi:906737626[pii]10.1080/08039480802626939

Petermann F, Petermann U (2007) Hamburg-wechsler-intelligenztest für kinder iv (hawik-iv). Hogrefe, Göttingen

Pliszka S (2009) ADHD and comorbid disorders: psychosocial and psychopharmacological interventions. Guilford Press, New York

Raine A, Dodge K, Loeber R, Gatzke-Kopp L, Lynam D, Reynolds C, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Liu J (2006) The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire: differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggressive Behavior 32(2):159–171

Rettew DC, Copeland W, Stanger C, Hudziak JJ (2004) Associations between temperament and dsm-iv externalizing disorders in children and adolescents. J Dev Behav Pediatr 25(6):383–391. doi:00004703-200412000-00001[pii]

Sareen J, Stein MB, Cox BJ, Hassard ST (2004) Understanding comorbidity of anxiety disorders with antisocial behavior: findings from two large community surveys. J Nerv Ment Dis 192(3):178–186. doi:00005053-200403000-00002[pii]

Scarpa A, Raine A (2004) The psychophysiology of child misconduct. Pediatr Ann 33(5):296–304

Schmeck K, Poustka F (2001) Temperament and disruptive behavior disorders. Psychopathology 34:159–163

Schmeck K, Goth K, Poustka F, Cloninger RC (2001) Reliability and validity of the junior temperament and character inventory. Int J Methods Psychiatric Res 10(4):172–182. doi:10.1002/mpr.113

Simonoff E, Elander J, Holmshaw J, Pickles A, Murray R, Rutter M (2004) Predictors of antisocial personality. Continuities from childhood to adult life. Br J Psychiatry 184:118–127

Sourander A, Jensen P, Davies M, Niemelä S, Elonheimo H, Ristkari T, Helenius H, Sillanmäki L, Piha J, Kumpulainen K, Tamminen T, Moilanen I, Almqvist F (2007) Who is at greatest risk of adverse long-term outcomes? The finnish from boy to a man study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:1148–1161

Vitaro F, Brendgen M, Tremblay RE (2002) Reactively and proactively aggressive children: antecedent and subsequent characteristics. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 43(4):495–505

Vloet TD, Herpertz S, Herpertz-Dahlmann B (2006) [aetiology and life-course of conduct disorder in childhood: Risk factors for the development of an antisocial personality disorder]. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother 34(2):101–114 (quiz 114–105)

Vloet TD, Konrad K, Herpertz SC, Matthias K, Polier GG, Herpertz-Dahlmann B (2010) development of antisocial disorders—impact of the autonomic stress system. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 78(3):131–138. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1109981

Walker JL, Lahey BB, Russo MF, Frick PJ, Christ MA, McBurnett K, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Green SM (1991) Anxiety, inhibition, and conduct disorder in children: I. Relations to social impairment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 30(2):187–191. doi:10.1097/00004583-199103000-00004

Washburn JJ, Romero EG, Welty LJ, Abram KM, Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Paskar LD (2007) Development of antisocial personality disorder in detained youths: the predictive value of mental disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 75(2):221–231. doi:2007-04141-003[pii]10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.221

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Polier, G.G., Herpertz-Dahlmann, B., Matthias, K. et al. Associations between trait anxiety and psychopathological characteristics of children at high risk for severe antisocial development. ADHD Atten Def Hyp Disord 2, 185–193 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-010-0048-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-010-0048-5