Abstract

Geoconservation has become a new trend worldwide, providing a rapid communication channel that directly affects all of humanity. In this context, the awareness of conservation and use of nature is directly proportional to the level of development/civilization. Especially in different countries and regions, the demand for continuous use should be evaluated due to the economic conditions of the Earth’s population and also for nature conservation reasons. The present study for Türkiye focuses on studies conducted on international platforms (Web of Sciences database) and national journals (both Turkish and English). According to the results of the bibliometric study, the number of papers published in more than fifty journals has increased dramatically, especially in the last 10 years. A re-evaluation of the impact analysis between the first starting point of this topic, the ‘Digne-Les-Bains Declaration’ (France 1991), and the most recent one, the ‘Chęciny Declaration’ (Poland 2018), perspectives, trend axes and intended interpretations are developed. Finally, this study consists of an explanation of the focus, scope and level of detail of the data generated over the past 12 years and includes a detailed review of the studies conducted for the impact area. Based on the bibliometrics and the review of the accessible literature, this article provides an overview of the current status of geoconservation in Türkiye.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Earth’s geological heritage and geoconservation have been increasingly focused on by multidisciplinary research groups since the twenty-first century. Geosite identification, geoconservation, geodiversity, geocultural heritage, geotourism and the geopark concept are closely interrelated and naturally serve conservation and also geoscience education and geotourism as an element of sustainable geoheritage (Theodossiou-Drandaki et al. 2004; Brilha et al. 2005; Dowling and Newsome 2005; Hose 2005; Ruban 2010; Henriques et al. 2011, 2019; Wimbledon and Smith-Meyers 2012; Dowling 2011, 2014; Brilha 2016, 2018; Escorihuela 2018). The broad definition of a geosite is an exceptional region that is threatened with poverty, and with the disappearance of knowledge about the region and geological documentation, all geological records will also be lost (Wimbledon 1996; Kazancı, 2010). The word geosite is not scale or size-dependent and can refer to any degree of geological diversity in an area, including rocks, landforms and other elements (Kazancı 2010; Köroğlu and Kandemir 2019). As Serrano and Ruis-Flano (2007) show, the term geosite is used in research as a broad term for specific sites and specific areas. Geoconservation is defined by Prosser et al. (2013) as an increasing activity that includes efforts to preserve and enhance ‘geological, geomorphological and soil features, processes, fields and samples’ as well as associated public outreach and awareness. Thus, geodiversity encompasses the diversification of the geoheritage and can be measured by defining geosite types, type equivalents and rank (Wang et al. 2015). The ProGEO group has compiled ten different categories covering all areas of the geoscience sector (ProGeo Group 1998; Kazancı et al. 2015). Another category, geoheritage, refers exclusively to the elements of geodiversity in each region of the world (Dixon 1996; Gray 2004, 2008; Bruno et al. 2014) and assumes that geodiversity will be maintained if geoheritage sites are protected. In addition, the term ‘geosite’ which refers to a geoheritage site as a place of scientific, historical and cultural significance that is accessible for visitation and other research, is recognized worldwide (ProGeo Group 1998; Cleal et al. 1999; Todorov and Wimbledon 2004; Ruban 2010; Wang et al. 2015). Geotourism is a selected form of nature tourism that is specifically related to natural values; geological, geomorphological and landscape features are combined (Dowling and Newsome 2005; Hose 2005; Dowling and Newsome 2010; Kazancı 2010; Dowling 2011, 2014; Köroğlu and Kandemir 2019; Özpay 2020; Özer and Mülayim 2022). Through enjoyment and learning, it promotes tourism, the protection of geological diversity and the understanding of geoscience (Newsome and Dowling 2010). Earth science disciplines focus on geology and include both ‘form’ (landforms, rock outcrops, different rock types, sediments, soils and crystals) and ‘process’ (volcanism, erosion and glaciers) (Dowling and Newsome 2010). Dowling and Newsome (2010) noted that the concept of geotourism and its market is growing worldwide. This is due to the growth of geoparks, but also to the independence of many historic and modern natural and urban areas, where tourism focuses on geosites rather than geological environments as indicated by Köroğlu and Kandemir (2019). The uniqueness of the geopark structure as a means of disseminating the value for the conservation and promotion of geosites related to geological heritage was first mentioned in the eighth point of the ‘Declaration of Digne’ (DD 1991), which states that ‘Man and the Earth share a common heritage of which we and our governments are the guardians’ (1. International Conference on Geological Heritage in Digne, France 1991; http://www.progeo.ngo/index.html; Patzack and Eder 1998; Wang et al. 2015).

Despite the need for geosite inventories, the lack of a systematic, legal and cultural approach in Türkiye has had a significant impact on this field in both science and tourism (Kazancı 2010, 2012; Akbulut 2016; Köroğlu and Kandemir 2019; Özer and Mülayim 2022). Moreover, the non-fast bureaucracy means that the promotion and protection of geosites can take a long time with unconscious processes in all countries of the same class, including Türkiye (Çetiner et al. 2018).

Materials and Methods

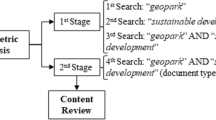

This study provides an overview of the state of geoconservation in Türkiye. The three-step methodology described by Herrera-Franco et al. (2021)—(i) search criteria and source identification, (ii) data extraction and (iii) data analysis and interpretation—was considered in the preparation of this tool. The source of publication data for this study is the Web of Science database. However, other published literature was also considered, including academic publications documenting journal articles and books if they are accessible online through other databases. In addition, they mainly refer to publications in the Turkish language that are not included in scientific databases. Data collection faced some limitations and may be incomplete due to the difficulty of accessing internal reports produced by national authorities and/or unpublished dissertations kept at universities, among other documents. All data collected are included in Tables 1 and 2.

The History of Geoconservation in Türkiye

The first approaches to culture, art, natural values and geological heritage in Türkiye date back to the Ottoman Empire period and have evolved with different concepts until today.

Osman Hamdi, who was appointed director of the Müze-i Hümâyun (Turkish) in 1881, ushered in a new era of Turkish museology (https://muze.gov.tr/muze-detay?SectionId=IAR01&DistId=IAR). His work in the field of culture and art was intensified by the museum directorate. He tried to bring together all works of historical and artistic value within the borders of the Ottoman state in the spirit of museology (https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/osman-hamdi-bey; https://muze.gov.tr/muze-detay?SectionId=IAR01&DistId=IAR). Thanks to his efforts, the 30-year-old Müze-i Hümâyun (Turkish) also became the İstanbul Museum of Archeology (https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/osman-hamdi-bey).

The main source of change is the scientific approach and issues of cultural change. In the phenomena that influence this development, man and science remain on one side, while the effectiveness of cultural structure and belief is more observable.

First stage

Since civilizations have settled down, we can closely observe and explore the production of detailed information about cultural heritage. The studies that can be considered as the first regulation for the protection of cultural heritage in our country are the Asar-ı-Atika Regulations, the first of which was issued in 1869 (Madran 1996). Cultural heritage conservation activities in Türkiye began in the late ninetennth century and were intensified in the second half of the twentieth century. In this context, inventorying and registration began, sites and boundaries were defined and administrative and organizational institutions were established throughout the country (Şakar 2022). Thanks to the visionary understanding of the young Türkiye Republic in the mid-twentieth century, the legal provisions on national parks in article 25 of Forestry Law No: 6831 of 1956 are considered the official beginning of Türkiye nature conservation studies and are the first steps towards institutionalizing nature conservation (https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/MevzuatMetin/1.3.6831.pdf, in Turkish).

In 1973, Law No. 1710 (EEK) was enacted, and with this law, the concept of a site was discussed for the first time. This brought to the fore not only individual buildings but also the protection of historic environments (Şahin and Kurul 2009). The enactment of Law No. 2863 on the Protection of Cultural and Natural Heritage (KTVK) in 1983, Law No. 5226 fundamentally amends this law in 2004, and Decree-Law No. 648 (KHK) in 2011. They are the most critical points in the organization of the protected area in Türkiye.

These protective measures were also extended to Cappadocia, one of the first regions in Türkiye for which a long-term national park development plan was prepared in 1968. In addition, the boundaries of protected areas were defined at the regional scale and inventories of individual buildings were carried out by a decision of the High Council for Immovable Antiquities and Monuments in 1976. The designation as a World Heritage Site in 1985 and as a National Park in 1986 strengthened the conservation status of Cappadocia at the national and international levels. However, in the 1990s and 2000s, a series of regulations were issued to protect the site, and a special conservation law for Cappadocia came into force in 2019.

The founder of the Türkiye Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, made great efforts in the field of education in order to explore Türkiye’s multi-layered cultural and geologic heritage, which has a diverse richness, and to understand its significance. Thanks to the scientists who came from modern universities and from abroad, and the scientists who completed their education abroad and returned to the country, important scientific studies were carried out and their foundations were laid. The first studies started in the middle of the twentieth century, led by İstanbul Technical University (İTU) and İstanbul University (İU). Although the foundations of the first studies were laid by Professors Cazibe Sayar, Hamit Nafiz Pamir, Nezihi Canıtez and İbrahim Enver Altınlı, the publications of Ketin (1970) and Öngür (1976) are considered the first studies on this subject.

Considering the great work mentioned above, geoscientists in Türkiye have always been sensitive to the geological heritage and have worked effectively to protect it within the limits of available resources. In the early 1970s, a group was formed within the framework of the Türkiye Geological Institute (TJK, in Turkish) to carry out publications and promotional activities. The ‘Earth and Human Journal’ partly served this purpose. Due to the development of the Natural History Museum (Ankara/Türkiye) in the General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration (MTA, in Turkish), the subject always remained on the agenda. However, all well-intentioned attempts had a short life span due to the lack of an organized system and ineffective legal regulations.

Development stage

After the ‘first steps’ in geoheritage/geoconservation issues, institutional efforts rather than personal initiatives emerged in the 1990s and 2000s.

The first institutional structure in Türkiye is the Geological Heritage Preservation Association (JEMİRKO_www.jemirko.org.tr), whose roots go back to the JEMİRKO (in Turkish) student community at Ankara University in 1997. Under the leadership of Prof. Dr. Nizamettin Kazancı and thanks to the joint initiatives of Ömer Emre and İbrahim Sönmez Sayılı, a meeting was held on May 27, 1999, with 77 delegates from geoscientists, academics and public institutions as the ‘Research and Protection Group for the Geological Heritage of Türkiye’. The Ministry of Culture and Tourism supported the establishment and participated with a representative. Ali Koçyiğit, Fuat Şaroğlu, Gerçek Saraç, Ömer Emre, Mutlu Gürler, Hülya İnaner, İbrahim Sönmez Sayılı and Nizamettin Kazancı were appointed to the provisional board, but the intervening earthquake disaster did not allow active work. In the course of time, the association was transformed into a society in December 2000 and held its first ordinary general assembly in March 2001. JEMİRKO (in Turkish) is the only non-governmental organization (NGO) on the subject and has been carrying out a series of activities on Geological Heritage for more than 20 years (İnaner et al. 2019). It has also conducted a study entitled ‘Türkiye Geological Heritage Inventory’ and published it in various publications (www.jemirko.org.tr).

Another institutional initiative launched in 2002 on the geological heritage was the Türkiye Academy of Sciences-Turkish Cultural Inventory (TÜBA-TÜKSEK, in Turkish) project under the Türkiye Academy of Sciences (TÜBA, in Turkish). This project is based on a study that aims to collect and organize all types of data describing Türkiye cultural assets in an integrated digital system and make them available for questionable use. Within the project, inventory sheets for elements and formations considered cultural heritage in the fields of archaeology, urban and rural architecture, ethnography, ethnobotany, oral history and geology were created and transferred to digital media (Yalçın 2021). Software with a wide range of algorithms has been developed for querying and generating new information in the digital environment. Geological heritage and geoarchaeology are covered under the title geology (Yalçın 2007). Prepared under the title ‘Natural Monuments Inventory’ for ‘Geological Heritage’ items. Unfortunately, since the TÜBA-TÜKSEK (in Turkish) project could not be continued due to the administrative changes within TÜBA, this second institutional initiative was no longer on the agenda and could not be continued (Yalçın 2021). However, some of the studies conducted in this project were published in the ‘Cultural Inventory Journal’, the publication organ of TÜBA (in Turkish), and presented to relevant stakeholders (Gürpınar et al. 2004; Yalçın et al. 2004; Ustaömer et al. 2005; Yalçın 2021).

The scientific studies conducted in 2003 by the General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration (MTA, in Turkish) within the framework of the ‘Research Project on Türkiye’s Geological Heritage’ (TÜJEMAP, in Turkish) with expert scientists on national and international platforms. The project, which started its work with the aim of determining the potential of cultural heritage in the selected pilot areas, has made the necessary proposals for the protection of the areas with high potential of cultural heritage as a result of the studies carried out subsequently. At the same time, in cooperation with other public institutions and organizations, as well as with universities, it started to transfer the inventory data of 367 proposed areas that have the potential to be geological cultural heritage sites to the database GIS, and to date the inventory is almost completed (https://www.mta.gov.tr/v3.0/birimler/tujemap).

In fourth place, the topic of ‘Cultural Geology and Geological Heritage’ has increasingly been on the agenda of the TMMOB’s Chamber of Geological Engineers since 2010. While sessions on cultural geology and geologic heritage added to the program during the Geology Congresses provide opportunities to discuss studies being conducted at universities and implementing agencies, Chamber officials continue to emphasize the importance and need to protect geologic heritage to society and decision makers through a variety of activities. In the 2010s, a number of publications were published, mostly based on personal efforts and/or projects at universities (Kazancı et al. 2008; 2015; Kazancı 2010, 2012, 2014; Güngör et al. 2012a, b; Çiftçi and Güngör 2016; Yalçın 2017). However, the intended impact on the platforms where these publications are presented was limited and could not be brought to an international point. Kazancı et al. (2015) published in the MTA (in Turkish) Journal entitled ‘Geological Heritage and Türkiye Geosites Roof List’ is a detailed and outstanding contribution to this topic. The books in the series ‘Geological Heritage in National Parks’ published by JEMİRKO (in Turkish) are among the publications that clearly show the richness of Türkiye on this topic (www.jemirko.org.tr). The publication titled ‘Geological Natural Heritage-The Importance of Geological Heritage and the Report on the Situation in Türkiye’ discusses the basic concepts on this topic and especially the legislation related to conservation (TMMOB Chamber of Geological Engineers 2019).

Future stage

As part of the process that began with Kazancı’s (2010) study of basic concepts in Türkiye, some studies were conducted to discuss the feasibility of geoconservation in areas with special geological structures and areas (Gümüş 2009, 2012, 2019; Hatipoğlu 2010; Kazancı 2012; Güngör et al. 2012a, b; Akbulut 2014a, b; Gümüş and Zouros 2014; Kazancı et al. 2015, 2019; Çiftçi et al. 2016; Üner et al. 2017; Citiroglu et al. 2017; Yürür et al. 2019; Çetiner et al. 2018; Doğan et al. 2019; Ateş and Ateş 2019; Köroğlu and Kandemir 2019; İnaner et al. 2019; Gürer et al. 2019; Güney 2020; Aydın and Yüceer 2020; Gül et al. 2020; Sümer et al. 2020; Çiftçi and Güngör 2021; Özer and Mülayim 2022).

Between 2010 and 2022, the next stage of international geoheritage and conservation research began in Türkiye. The publications produced during the past period (12 years) were published on 11 different platforms by 19 different institutions (Fig. 1a). The total number of publications was 34 books and articles. There were about 3 publications on this topic per year (Fig. 1b). In terms of publications, it can be seen that the prominent universities in Ankara, the capital of Türkiye Ankara, are in the lead (Fig. 1a). Geo-(geological) heritage, tourism and conservation studies were conducted (Hatipoğlu 2010; Kazancı 2012; Akbulut 2014a, b, 2016; Üner et al. 2017; Citiroglu et al. 2017; Çetiner et al. 2018; Çetin et al. 2018; Yürür et al. 2019; Doğan et al. 2019; Ateş and Ateş, 2019; Köroğlu and Kandemir 2019; İnaner et al. 2019; Kazancı et al. 2019; Gürer et al. 2019; Aydın and Yüceer 2020; Gökçe et al. 2020; Çelik and Sert 2020; Sümer et al. 2020; Güney 2020; Gül et al. 2020; Özpay 2020; Isık-Çaktı et al. 2021; Erginal et al. 2021; Yüceer et al. 2021; Ertekin et al. 2021; Ertek 2021; Özgeriş and Karahan 2021; Özçelik 2022; Özer and Mülayim 2022; Kazancı and Lopes 2022; Karadeniz et al. 2022; De Vries et al. 2022), in different branches is made, on the international platforms from Türkiye between 2010 and 2022 (Figs. 1a, b and 2a–c).

Specifically, asymmetric development and numerical differences can be observed in all scientific publications (Fig. 2a–c). The produced publications are represented by a total of 34 in Türkiye, mainly journals (30) and books (4) (Fig. 2a). It was found that the publications produced are directly proportional to the academic title, and as the academic maturity increases, the number and effectiveness of publications increase (Fig. 2b). The most important issue is gender equality or social representation, and the fact that the ratio of men to women in publications is almost double shows that new female researchers working on the topic should be supported (Fig. 2c).

As mentioned above, the process of recording and protecting our geological heritage has been underway since the 1970s, and despite the efforts started 50 years ago, the level achieved today is unfortunately far from satisfactory.

UNESCO Global Geoparks are areas where conservation, sustainable development and community participation can be implemented together; they are increasingly recognized in the world. These areas of international importance are areas managed with an integrated approach to geoconservation, geoeducation, geotourism and sustainable development. In 2001, UNESCO, began working with geoparks, and in 2004, the Global Geopark Network (GGN) was established in Paris. In 2015, at the 38th General Conference of UNESCO, the status of Geoparks was changed and it was decided by UNESCO to become a UNESCO program where international registration is possible. The ‘Charter of the International Geoscience and Geoparks Program (IGGP)’ was adopted and the concept of UNESCO Global Geopark was developed. As of 2021, there are 177 geoparks from 46 countries in the UNESCO Global Geopark Network. The first and only UNESCO Geopark in Türkiye is Kula-Salihli UNESCO Global Geopark in Manisa (Gümüş 2012). Although there have been various initiatives over time, none has been as large as the studies conducted specifically for Kula.

Recently, Pamukkale and Göreme National Park (the Rock Sites of Cappadocia) were included in the ‘Top 100 Geological Heritage Sites’ according to the World Heritage List UNESCO (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/485/).

The Pamukkale contains calcite-rich waters of hot springs, springing from a cliff almost 200 m high above the plain, have created a breath-taking landscape in Pamukkale. This mineralized water has created a series of petrified waterfalls, stalactites and pools with step-like terraces, some of which are less than 1 m high, while others are up to 6 m high. Fresh deposits of calcium carbonate give these formations a brilliant white coating. The Turkish name Pamukkale, meaning ‘cotton castle’, derives from this impressive landscape (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/485/).

Göreme National Park and the rocky sites of Cappadocia have a spectacular landscape in which the forces of erosion are dramatically expressed. The Göreme Valley and its surroundings offer a world-renowned and accessible display of hoodoo landforms and other erosional features that are of great beauty and interact with the cultural elements of the landscape (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/357/).

However, every year, many of our geological cultural assets are rapidly disappearing or are threatened with extinction. There are many approaches and methods to raise awareness of geological heritage and the need for its protection in society and to create awareness for conservation (Enniouar et al. 2015). Unfortunately, attempts to implement it and achieve results are still unsatisfactory. It is clear that this goal can be achieved with approaches such as the creation of registered geoparks and the identification and protection of geosites. However, the studies and legislative problems required to implement actions in this area should also be considered. By integrating other approaches, bureaucratic measures and practices that can be more easily and widely applied, it may be possible to solve the problems quickly and thus ensure sustainability.

The Situation Analysis in Türkiye

The use of WOS (Web of Science) in this study is due to the rigorous process of collecting scientific articles. This analysis reveals trends in the topics studied. The comparative analysis included correlations between institutions/publication numbers, journal names, resources (books and/or journals), publication trends, author details and genders. Figure 1a shows the number of publications in Türkiye between 2010 and 2022 compared to the ranking of universities. The top two universities (Ankara and Dokuz Eylül) stand out in terms of the number of publications. Figure 1b shows an overview of the journal name and the volume of major publications. The name of the leading journal is Geoheritage. Figure 2 a, b, and c indicates numerical comparisons in different titles, publication portals, number of publications by academic title and number of publications by gender. When comparing journal and book resources, journals lead (30%) compared to 4% of book resources. Regarding the title of the editor, the following structure emerged: 18% professors, 6% assistant professors, 6% assistant professors and 4% graduate students. Regarding demographic characteristics, such as gender, 12% were female and 22% were male. In summary, current developments include geoeducation, which can serve as a guide for future studies (Herrera-Franco et al. 2022). Learning opportunities and interactions for local people and visitors are also values of geoeducation (Németh and Moufti 2017; Herrera-Franco et al. 2022).

The collected tables and figures illustrate that the different aspects of geoconservation in Türkiye are regional. Most of them (62%) are related to geoheritage,, i.e., they belong to the efforts of identifying and analysing regions located mainly on the west and south coasts of Türkiye, and thus to basic geoconservation (Figs. 3 and 4). Although the implementation of geoconservation is relatively limited to geotourism activities (29%), geoconservation is still underdeveloped (9%) (Fig. 4). The results also indicate that there are several forms of geoheritage in Türkiye, an aspect that relates to actual geoconservation, but geoheritage diagnosis is only partially established. There is a lack of geoeducation and geoconservation in Türkiye. The development of geoeducational and geotourism resources that meet the goals of geoconservation is a great help in the development of geoheritage-based programs that promote social and economic progress (Köroğlu and Kandemir 2019; Özer and Mülayim 2022). This type of support for geoheritage exists mainly in countries where there are also legal instruments and public policies for conservation. These results will make it possible to create a roadmap for geoconservation in this field, which will help decision-makers to set specific priorities for geoconservation in Türkiye. Engaging society in geoconservation through formal and informal local efforts can be a critical component in jointly managing conservation plans and supporting local equity, with the goal of preserving geoheritage (Neto and Henriques 2022). This goal can be strongly promoted through geoconservation and geoeducation activities.

Map showing the geo-(geological) heritage, tourism and conservation studies in different regions of Türkiye between 2010 and 2022 (references therein and Table 1)

Discussion

Geoheritage Framework of Türkiye

Geoheritage theme related to the paper, we see that Türkiye is represented by thirteen different publications (Hatipoğlu 2010; Kazancı 2012; Akbulut 2014a, b, 2016; Üner et al. 2017; Citiroglu et al. 2017; Çetiner et al. 2018; Çetin et al. 2018; Yürür et al. 2019; Doğan et al. 2019; Ateş and Ateş 2019; Köroğlu and Kandemir 2019; İnaner et al. 2019; Kazancı et al. 2019; Gürer et al. 2019; Aydın and Yüceer 2020; Gökçe et al. 2020; Çelik and Sert 2020; Sümer et al. 2020; Güney 2020; Özpay 2020; Cengiz et al. 2021; Isık-Çaktı et al. 2021; Erginal et al. 2021; Yüceer et al. 2021; Ertekin et al. 2021; Ertek 2021; Özçelik 2022; Özgeriş and Karahan 2021; Özer and Mülayim 2022; Kazancı and Lopes 2022; Karadeniz et al. 2022; De Vries et al. 2022) (Table 1, Fig. 3).

Most of the 90 national articles are directly related to geoheritage, geoconservation, geotourism, assessment, geosite inventory, geoparks, geomorphosite and geoscience education (Table 2). The contents of Table 2 also provided a better understanding of the geographic distribution of the study area and its relationship to the fields where the study was managed. Most of these works aim to initiate and publicize the evaluation of the area from the description and characterization of the elements of geoconservation to the application of the methods established in the scientific literature for the evaluation and inventory of geosites. Regarding the methodological procedures used in the analyzed articles, many works are recommended as case studies. In these, in addition to presenting and inventorying the elements of geodiversity, a description and characterization of the main features and geosites present in the areas are made. These characterizations generally relate to theoretical aspects and knowledge of geology, geomorphology and other fields related to the geosciences, and usually attempt to portray the unique character and scenic beauty or importance of each element of geodiversity in terms of potential, education, science and economy.

With the increase in the number of these publications, the attention of our country and the world can be attracted to some extent. To further increase the number of these publications, we can consider all geological values and our study areas as a common heritage of mankind and recognize the existence of this heritage everywhere on Earth. We cannot expect anyone to identify a geological object that they do not know, to have access to information about that object or to know its significance. The responsibilities associated with this position, therefore, require an above-average commitment from colleagues who can apply geoscience expertise to any field.

Geoconservation Framework of Türkiye

The issue of protection raises some legal and traditional problems both in Türkiye and in the rest of the world. Due to population growth, all non-renewable resources in the world are consumed by industrial production and demand for raw materials. These resources consist of 90% non-renewable material, and many of them are such that they cannot be recovered. Here, Türkiye, like all developing countries, is in a balance between conservation and utilization. However, in Türkiye, the preference for utilization over effective conservation has gained weight. Although it seems impossible to speak of an effective ‘Geoconservation Framework’ with these preferences, the structural and institutional developments described in ‘Discussion’, ‘Geoheritage Framework of Türkiye’, ‘Geoconservation Framework of Türkiye’ and ‘Where is the Problem?’ sections are not sufficient. Only when the global conservation perspective reaches US, European, and Chinese standards for Türkiye can we speak of a ‘Geoconservation Framework’.

At this stage, the ‘Geoconservation Framework’ in Türkiye is still in its infancy due to the fragmentation of government structures and bodies, problems with different responsibilities, scientific deficits, insufficient institutional coordination and problems with social knowledge and perspective.

Where is the Problem?

Türkiye, with its historical geological development, geographical location and the contributions of all civilizations living on it, has unique values on both regional and global levels. These values appear as conscious-unconscious and/or protected-destroyed. The success of countries that are strong in all aspects of protection, especially in all aspects of the system, increases significantly. However, underdeveloped countries or developing countries that are inferior both in terms of the efficiency of government agencies and in terms of legislation and bureaucracy are the factors that disrupt the concept of geoconservation and lead to failure.

In listing the inaccurate issues;

-

1.

Principles and frameworks should be incorporated into the systems of the relevant organizations.

-

2.

Geo-education curricula and the lack of implementation: curricula are about educational institutions.

-

3.

Criminal penalties and deficiencies in the legal system: fewer deterrent penalties than on a world scale.

-

4.

Inability to deal with special units or corporate identity: Lack of a single point of contact to follow up with a competent institution.

-

5.

Lack of social awareness and non-governmental organizations: The main power is the population, but the lack of repressive and effective follow-up for the entire.

Suggestions for Future Potential

Social consciousness and academic culture, or the existence of universities in a universal sense, first reveal the concept of ‘Geoconservation’. However, the permanence and sustainability of these effects are only made possible by the existence of state institutions and legislative and enforcement structures. The effectiveness of the work carried out with the contributions of all components stems from the shared vision of both governmental and non-governmental organizations around the world. It is understood that instead of the existence of individual structures, a social, global or priority policy is required to unlock the potential in this area. The potential impact, respectively;

-

1.

Türkiye: It has very important and special values that must be protected together with all other cultural and natural heritage via Geological Education (Van Loon 2008).

-

2.

Due to its geographical location, the synergy between the geological history and the history of civilizations has characteristics that can be considered as a laboratory for the rest of the Earth.

-

3.

Türkiye, which is in a globally important geopolitical position, should direct its future development plans to the preservation of cultural heritage and focus on tourism revenues.

-

4.

One of the most important achievements of developing countries is tourism revenue, which does not require high investment because they have natural potential and natural resources. If Türkiye fulfils its duties and responsibilities in these areas, it will be a role model worldwide.

-

5.

If we succeed in introducing the concepts of ‘Geoconservation’ and ‘Geoheritage’ into education and social life, the mistakes of the past will not be repeated in the future. In this way, we can bring a very bright future to conservation and heritage concerns.

Conclusions

This study examined Türkiye, which is a rare country that holds cultural, social and geological values. Studies on the historical process, major developments and milestones were examined in both the native language (Turkish) and international languages (English). From the data obtained, the concept of ‘Geoconservation’ has been present in the geography of Türkiye since the end of the nineteenth century. The concept, which was represented by individual studies rather than institutional contributions during the studied period, was institutionalized and systematized in the twentieth century. With the concept that is currently evolving, both the social and scientific sectors of the country are studying very openly and continue to contribute to the subject. Türkiye, which is an important platform with its contribution to scientific literature, diversity of research and increase in the number of experts (academics and interested citizens), has shown clear signs that it will take a more influential position in the future. In summary, the concept of protection that corresponds to the level of development does not yet occupy the desired position in Türkiye, but it is above the development standards in a global comparison.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Acar D (2008) Jeoparklar: Pamukkale örneği. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Yatırım ve İşletmeler Genel Müdürlüğü. Uzmanlık Tezi, Ankara (in Turkish)

Akbulut G (2014a) Önerilen Levent Vadisi Jeoparkı’nda Jeositler. Cumhuriyet Üniv Sosyal Bilimler Derg 38(1):29–45 (in Turkish)

Akbulut G (2014b) Volcano tourism in Turkey. Volcanic Tourist Destinations. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 89–102

Akbulut G (2016) Geotourism in Turkey. Alternative tourism in Turkey. Springer, Cham, pp 87–107

Akbulut G, Özgen-Erdem N, Ayaz E, Ocak F (2017) Yeni bir jeoturizm Sahası: Emirhan Kayalıkları (Sivas). Sosyal Bilimler Derg (SOBİDER) 4(14):15–29 (in Turkish)

Altınlı İE (1978) Niçin Açık Hava Müzesi? Yeryuvarı Ve İnsan 3(3):29–30 (in Turkish)

Altınlı İE (1978) Bilecik Açık Hava Müzesi. Yeryuvarı Ve İnsan 3(3):30 (in Turkish)

Arpat E (1976) İnsan ayağı izi fosilleri: Yitirilen bir doğal anıt. Yeryuvarı Ve İnsan 1(2):3–4 (in Turkish)

Arpat E, Yılmaz G (1976) Göktaşı çukuru mu? Çökme çukuru mu? Yeryuvarı Ve İnsan 1(1):12–14 (in Turkish)

Aslan F (1977) Aksaray Taş Devri Fosil İnsanı ve Endüstrisi. Yeryuvarı ve İnsan 2(4):5–8

Ateş Y (2016) The significance of historical mining sites as cultural/heritage resources a case study of Zilan historical mining site, Erçiş, Van, Turkey. MT Bilimsel 9:15–24 (in Turkish)

Ateş HÇ, Ateş Y (2019) Geotourism and rural tourism synergy for sustainable development-Marçik Valley case-Tunceli, Turkey. Geoheritage 11:207–215

Aydın R, Yüceer H (2020) Impacts of tourism-led constructions on geoheritage sites: the case of Gilindire Cave. Geoheritage 12:42

Aytaç AS, Demir T (2019) Kula UNESCO Global Jeoparkı’nda Yerbilimleri ve Jeomiras Açısından Uluslararası Öneme Sahip Üç Yeni Jeosit Önerisi. Akdeniz İnsani Bilimler Derg 9(2):125–140 ((in Turkish))

Bağcı HR, Karadurak S (2022) Durağan’ın (Sinop) Jeoturizm Açısından Değerlendirilmesi. Jeomorfolojik Araştırmalar Derg Bül 8:1–27 (in Turkish)

Bahadır M, Işık F (2021) Şavşat peribacalarının (Artvin) jeomorfolojisi ve jeoturizm potansiyeli. Kesit Akad Derg 7(26):145–160 (in Turkish)

Boyraz S, Yedek Ö (2012) Kızılcahamam-Çamlıdere Jeoparkı. TMMOB Jeol Mühendisleri Odası Haber Bül 2:21–24 (in Turkish)

Brilha J, Andrade C, Azerêdo A, Barriga FJAS, Cachão M, Couto H, Cunha PP, Crispim JA, Dantas P, Duarte LV, Freitas MC, Granja MH, Henriques MH, Henriques P, Lopes L, Madeira J, Matos JMX, Noronha F, Pais J, Piçarra J, Ramalho MM, Relvas JMRS, Ribeiro A, Santos A, Santos V, Terrinha P (2005) Definition of the Portuguese frameworks with international relevance as an input for the European geological heritage characterisation. Episodes 28(3):177–186

Brilha JB (2016) Inventory and quantitative assessment of geosites and geodiversity sites: a review. Geoheritage 8:119–134

Brilha JB (2018) Geoheritage: Inventories and evaluation. Geoheritage Assess Prot Manag pp 69–85

Bruno DE, Crowley BE, Gutake JM, Moroni A, Nazarenko OV, Oheim KB, Ruban DA, Tiess G, Zorina SO (2014) Paleogeography as geological heritage: developing geosite classification. Earth Sci Rev 138:300–312

Canik B (1972) Jeoloji mostralarına saygı. TJK Yıllık Bülteni (in Turkish)

Canpolat E (2022) Evaluation of geomorphosite potential and the tourism attractiveness of Uçansu Waterfall (Gündoğmuş-Antalya). Geogr Plan Tour Studios 2(1):21–32

Canpolat E, Çılğın Z, Bayrakdar C (2020) Jeomorfoturizm Potansiyeli Bakımından Emecik Kanyonu – Şelalesi (Çameli, Denizli). Jeomorfolojik Araştırmalar Derg 5:64–86 (in Turkish)

Cengiz C, Şahin S, Cengiz B, Bahar-Başkır M, Keçecioğlu-Dağlı P (2021) Evaluation of the visitor understanding of coastal geotourism and geoheritage potential based on sustainable regional development in western Black Sea region, Turkey. Sustainability 13(21):11812

Cleal CJ, Thomas BA, Bevins RE, Wimbledon WA (1999) GEOSITES–an international geoconservation initiative. Geol Today 15(2):64–68

Çalık A, Kapan S, Erenoğlu RC, Erenoğlu O, Yaşar C, Ulugergerli EU (2018) Biga Yarımadasında Jeodeğerler ve Jeoturizm Potansiyeli. Türk Jeol Bül 61(2):175–192 (in Turkish)

Çetin M, Onac AK, Sevik H, Canturk U, Akpinar H (2018) Chronicles and geoheritage of the ancient Roman city of Pompeiopolis: a landscape plan. Arab J Geosci 11:798

Citiroglu HK, Isik S, Pulat O (2017) Utilizing the geological diversity for sustainable regional development, a case study, Zonguldak (NW Turkey). Geoheritage 9(2):211–223

Çelik MY, Sert M (2020) An assessment of pore size distribution changes of the andesite (İscehisar, Turkey) used as building stone of cultural heritages in relation to the artificial accelerated ageing factors. Geoheritage 12:71

Çetiner ZS, Ertekin C, Yiğitbaş E (2018) Evaluating scientific value of geodiversity for natural protected sites: the Biga Peninsula, northwestern Turkey. Geoheritage 10(1):49–65

Çiftçi Y, Güngör Y (2016) Jeopark Projeleri Kapsamındaki Doğal ve Kültürel Miras Unsurları İçin Standart Gösterim Önerileri. Maden Tetkik Aram Derg 153(24):304–334 (in Turkish with English version)

Çiftçi Y, Güngör Y, Havzoğlu T (2016) Bağdat demiryolları, Ereğli-Pozantı-Yenice (Orta Toroslar) arasının jeotravers özellikleri ve kültürel jeoloji olanakları. 69. Türkiye Jeoloji Kurultayı, Bildiri Özleri Kitabı, Ankara, pp 218–221 (in Turkish)

Çiftçi Y, Güngör Y (2021) Nemrut-Süphan öneri jeopark alanında (Bitlis-Türkiye) doğal ve kültürel miras bütünleşmesi ile jeokoruma önerileri. Maden Tetkik Aram Derg 165:191–215 (in Turkish with English version)

Derinöz B (2021) İncesu kanyonu ve çevresinin (Çorum) jeoturizm potansiyeli. Motif Akademi Halkbilimi Derg 14(34):792–813 (in Turkish)

De Vries BVW, Karatson D, Gouard C, Németh K, Rapprich V, Aydar E (2022) Inverted volcanic relief: its importance in illustrating geological change and its geoheritage potential. Int J Geoheritage Parks 10(1):47–83

Dixon G (1996) Geoconservation: an International review and strategy for Tasmania. Tasmania, Australia, Parks and Wildlife Service, pp 1–101

Doğan U, Şenkul Ç, Yeşilyurt S (2019) First paleo-fairy chimney findings in the Cappadocia region, Turkey: a possible geomorphosite. Geoheritage 11(2):653–664

Doğaner S (1997) A heritage of Anatolia: Pamukkale. Review 4:99–116 (in Turkish)

Dowling R, Newsome D (2005) Geotourism. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Dowling R, Newsome D (2010) Geotourism: a global activity. In: Dowling R, Newsome D (eds) Global Geotourism Perspectives. Goodfellow Publishers, Woodeaton, pp 1–17

Dowling RK (2011) Geotourism’s global growth. Geoheritage 3(1):1–13

Dowling RK (2014) Global geotourism—an emerging form of sustainable tourism. Czech J Tour 2:59–79

Dölek İ, Şaroğlu F (2017) Muş ili ve yakın çevresinde jeoturizm açısından değerlendirilebilecek jeositler. Fırat Üniv Sosyal Bilimler Derg 27(2):1–16 (in Turkish)

Enniouar A, Errami E, Lagnaoui A, Bouaala O (2015) The Geoheritage of the Doukkala-Abda Region (Morocco): an opportunity for local socio-economic sustainable development. In: Errami E, Brocx M, Semeniuk V (eds) From Geoheritage to Geoparks. Geoheritage, Geoparks and Geotourism. Springer Cham, Switzerland

Erginal AE, Öniz H, Erenoğlu O, Sarıaltun S (2021) An under-recognised geoarchaeological heritage asset in Turkey: Dana Island, Mersin. Geoheritage 13:89

Ertek TA (2021) The geoheritage of Göreme National Park and the rock sites of Cappadocia, Turkey. Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie. https://doi.org/10.1127/zfg_suppl/2021/0702

Ertekin C, Ekinci YL, Büyüksaraç A, Ekinci R (2021) Geoheritage in a mythical and volcanic terrain: an inventory and assessment study for geopark and geotourism, Nemrut Volcano (Bitlis, Eastern Turkey). Geoheritage 13:73

Erturaç MK, Okur H, Ersoy B (2017) Göllüdağ Volkanik Kompleksi İçerisinde Kültürel ve Jeolojik Miras Öğeleri, Türkiye. Jeol Bül 60(1):1–18 (in Turkish)

Escorihuela J (2018) The role of the geotouristic guide in Earth science education: towards a more critical society of land management. Geoheritage 10:301–310

Gökçe MV, İnce İ, Okuyucu C, Doğanay O, Fener M (2020) Ancient ısaura quarries in and around Zengibar Castle (Bozkır, Konya), Central Anatolia, Turkey. Geoheritage 12:69

Gray M (2004) Geodiversity: valuing and conserving abiotic nature. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, UK, p 434

Gray M (2008) Geodiversity: the origin and evolution of a paradigm. In: Burek CV, Prosser CD (eds) The History of Geoconservation. Geol Soc Spec Publ 300:31–36

Gül M, Küçükuysal C, Çetin E, Ataytür Ö, Masud A (2020) Coastal Erosion Threat on the Kızkumu Spit Geotourism Site (SW Turkey): Natural and Anthropogenic Factors. Geoheritage 12:54

Gül A, Özkul M (2023) Çal Kanyonu ve Çevresinin (Denizli, GB Anadolu) Jeolojik-Jeomorfolojik Özellikleri ve Jeoturizm Potansiyeli. Türk Jeol Bül 66(1):107–126 (in Turkish)

Gümüş E (2009) Çamlıdere fosil ormanı: Avrupa jeoparklar ağı kapsamında. 62. Türkiye Jeoloji Kurultayı, Bildiri Özleri Kitabı, pp 278, Ankara (in Turkish)

Gümüş E (2012) Türkiye’nin İlk Jeoparkına Doğru-Kula Volkanik Jeoparkı Projesi, I. Ulusal Coğrafya Sempozyumu (28–30 Mayıs 2012), Erzurum, pp 1081–1088 (in Turkish with English abstract)

Gümüş E, Zouros N (2014) Kula Jeoparkı Türkiye'nin ilk ve tek Avrupa ve UNESCO Global Jeoparkı. 67. TJK. Bildiri özleri kitabı, pp 412–413. Ankara (in Turkish with English abstract)

Gümüş E (2019) UNESCO Jeoparkları ve Jeomorfoloji. Jeomorfolojik Araştırmalar Derg 2019(3):17–27 (in Turkish with English abstract)

Güney Y, Yasak Ü (2018) Geotourism potential of the Yellimera canyon in Manisa. In: Efe R, Koleva I, Öztürk M, Arabacı R (eds) Recent Advances in Social Sciences. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, UK, pp 335–346

Güney Y (2020) The geomorphosite potential of the Badlands around Küpyar, Manisa, Turkey. Geoheritage 12:21

Güney Y (2022) Türkiye’deki Kırgıbayırların Jeosit Potansiyeli. Jeol Mühendisliği Derg 46:51–79 (in Turkish)

Günok E (2017) Türkiye’de Mevcut İlk ve Orta Öğretim Programlarının Jeomiras ve Jeopark Bilincinin Oluşmasına Etkileri. Türk Jeol Bül 60(1):1–10 (in Turkish)

Gürler M (2001) Anıt nitelikli jeolojik oluşumlar ve koruma çalışmaları. JMO Mavi Gezegen Popüler Yerbilim Derg 4:10–11 (in Turkish)

Gürler G, Öztan NS, Uğuz MF (2009) Türkiye’nin ilk Jeoparkı. JMO Mavi Gezegen Popüler Yerbilim Derg 14:9–20 (in Turkish)

Güngör Y (2009) Doğanın Öyküsünü Anlamak: Jeoturizm. JMO Mavi Gezegen Popüler Yerbilim Dergisi 14:4–8 (in Turkish)

Güngör Y, İskenderoğlu L, Azaz D, Güngör B (2012a) Levent Vadisi (Akçadağ-Malatya) Jeopark Envanter Çalışması, 65. Türkiye Jeoloji Kurultayı, 2–6 Nisan, pp324–325 Ankara (in Turkish with English version)

Güngör Y, Azaz D, Çelik Y, Yalçın MN (2012b) Narman Vadisinin (Narman-Erzurum) Jeopark Olarak Değerlendirilmesi 65. Türkiye Jeoloji Kurultayı, Ankara, Türkiye, 02–06 Nisan 2012, pp 326–327 Ankara (in Turkish with English version)

Gürer A, Gürer ÖF, Sangu E (2019) Compound geotourism and mine tourism potentiality of Soma region, Turkey. Arab J Geosci 12:734

Gürpınar O, Yalçın MN, Gözübol AM, Tuğrul A et al (2004) Birecik (Şanlıurfa) Yöresinin Temel Jeolojik Özellikleri ve Jeolojik Miras Envanteri. TÜBA Kült Envanteri Derg 2:157–168 (in Turkish with English abstract)

Gürsoy FD (2001) Ürgüp’teki Jeolojik Miras Etkinliği Üzerine. JMO Mavi Gezegen Popüler Yerbilim Dergisi 4:25 (in Turkish)

Hatipoğlu M (2010) Gem-quality diaspore crystals as an important element of the geoheritage of Turkey. Geoheritage 2(1–2):1–13

Hatipoğlu ŞC, Bahadır M (2020) Altınordu (Ordu) İlçesindeki Jeosit ve Jeomorfositlerin Turizm Potansiyellerinin “Preliminary Geosite Assessment Model (GAM)” ile Ölçümü. Mavi Atlas 8(2):548–564 (in Turkish)

Henriques MH, Pena dos Reis R, Brilha J, Mota TS (2011) Geoconservation as an emerging geoscience. Geoheritage 3(2):117–128

Henriques MH, Canales ML, García-Frank A, Gomez-Heras M (2019) Accessible geoparks in Iberia: a challenge to promote geotourism and education for sustainable development. Geoheritage 11(2):471–484

Herrera-Franco G, Montalván-Burbano N, Carrión-Mero P, Jaya-Montalvo M, Gurumendi-Noriega M (2021) Worldwide Research on Geoparks through Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 13:1175

Herrera-Franco G, Carrión-Mero P, Montalván-Burbano N, Caicedo-Potosí J, Berrezueta E (2022) Geoheritage and Geosites: A Bibliometric Analysis and Literature Review. Geosciences 12(4):169

Hose TA (2005) Geotourism and interpretation. In: Dowling RK, Newsome D (eds) Geotourism. Elsevier, Oxford, UK, pp 221–241

Isık-Çaktı S, Pulat O, Keskin-Çıtıroğlu H (2021) An example of geosite evaluation of fossils: Zonguldak Coal Basin (Turkey). In: Singh RB, Wei D, Anand S (ed) Global Geographical Heritage, Geoparks and Geotourism. Springer, Singapore, pp 133–145

İnan N (2008) Jeolojik Miras ve Doğa Tarihi Müzeleri. TÜBİTAK Bilim Ve Teknik Derg 493:80–83 (in Turkish)

İnan N (2011) Jeolojik Rotalar ve Jeoturizim Yol Hikayeleri. TÜBİTAK Bilim Ve Teknik Derg 524:38–47 (in Turkish)

İnaner H, Sümer Ö, Akbulut M (2019) New geosite candidates at the western termination of the Büyük Menderes Graben and their Importance on science education. Geoheritage 11:1291–1305

Jemirko (2002) Türkiye Jeolojik Miras Ögeleri Envanteri. JEMİRKO, Ankara (in Turkish)

Karadurak S, Bağcı HR (2021) Durağan'daki (Sinop) jeomorfositler ve sürdürülebilir kullanımı. MSc. Thesis. Ondokuz Mayıs Üniversitesi, Samsun, Türkiye (in Turkish with English abstract)

Kayan İ (1992) Demirköprü baraj gölü batı kıyısında Çakallar volkanizması ve fosil insan ayak izleri. Ege Coğrafya Derg 6:1–32 (in Turkish)

Kayğılı S, Aksoy E (2017) Kovancılar (Elâzığ, Türkiye) Jeositi: Nummulites’li seviyeler ve Antiklinal. Fırat Üniv Mühendislik Bilimleri Derg 29(1):293–299 (in Turkish)

Kayğılı S, Avşar N, Aksoy E (2017) Paleontolojik Bir Jeosit Örneği: Hasanağa Deresi, Akçadağ, Malatya. Türk Jeol Bül 60(1):1–14 (in Turkish)

Karadeniz E, Er S, Boyraz Z, Coşkun S (2022) Evaluation of potential geotourism of Levent Valley and its surroundings using GIS route analysis. Geoheritage 14:77

Kazancı N (2000) Yerkürenin hakları ve jeolojik miras. Cumhuriyet Bilim Teknik Derg 708:2 (in Turkish)

Kazancı N (2001) Jeolojik Miras Üzerine. JMO Mavi Gezegen Popüler Yerbilim Derg 4:4–9 (in Turkish)

Kazancı N, Şaroğlu F, Kırman E, Uysal F (2004) Doğal miras büyük tehdit altında. JMO Mavi Gezegen Popüler Yerbilim Derg 10:4–9 (in Turkish)

Kazancı N (2005) Kültürel Jeoloji. JMO Mavi Gezegen Popüler Yerbilim Derg 12:4–5

Kazancı N, Suludere Y, Mülazımoğlu NS, Tuzcu S, Mengi H, Hakyemez Y, Mercan N (2007) Milli Parklarda Jeolojik Miras-1; Soğuksu Milli Parkı ve Çevresi Jeositleri: Doğa Koruma ve Milli Parklar Genel Müdürlüğü, Jeolojik Mirası Koruma Derneği Yayını, Ankara, pp 59 (in Turkish)

Kazancı N, Şaroğlu F, Boyraz S (2008) İstanbul ve Ankara'da Yok Olmuş Jeositler. Bildiri Özleri Kitabı, 61. Türkiye Jeoloji Kurultayı, 24–28 Mart 2008, Ankara, 161–162 (in Turkish)

Kazancı N (2010) Jeolojik Koruma; Kavram ve Terimler. Jeolojik Mirası Koruma Derneği Yayını, 60 ss, Ankara (in Turkish)

Kazancı N (2012) Geological background and three vulnerable geosites of the Kızılcahamam-Çamlıdere Geopark project in Ankara, Turkey. Geoheritage 4(4):249–261

Kazancı N, Şaroğlu F, Doğan A, Mülazımoğlu N (2012) Geoconservation and geo-heritage in Turkey. In: Geoheritage in Europe and its Conservation (Ed. W.A.P. Wimbledon ve S. Smith-Meyer), ProGeo Spec. Pub, Oslo, Norway, pp 366–377

Kazancı N, Gürbüz A (2014) Jeolojik miras nitelikli Türkiye doğal taşları. Türk Jeol Bül 57:19–44 (in Turkish)

Kazancı N (2014) Şehircilikte Jeolojik Miras ve İstanbul Büyükşehir’in Yok Olan Jeo- değerleri. Genişletilmiş Bildiri Özleri Kitabı, İstanbul'un Jeolojisi Sempozyumu 4, 26–27–28 Aralık 2014, İstanbul, pp125–129 (in Turkish)

Kazancı N, Şaroğlu F, Suludere Y (2015) Geological heritage and framework list of the geosites in Turkey. Bull Mineral Res Explor 151:261–270 (in Turkish and English version)

Kazancı N, Özgen-Erdem N, Erturaç MK (2017) Kültürel Jeoloji ve Jeolojik Miras: Yerbilimlerinin Yeni Açılımları. Türk Jeol Bül 60(1):1–16 (in Turkish)

Kazancı N, Suludere Y, Özgüneylioğlu A, Mülazımoğlu NS, Şaroğlu F, Mengi H, Boyraz-Aslan S, Gürbüz E, Yücel TO, Ersöz M, İleri Ö, İnaner H, Gürbüz A (2019) Mining heritage and relevant geosites as possible instruments for sustainable development of miner towns in Turkey. Geoheritage 11:1267–1276

Kazancı N, Lopes ÖA (2022) Stones of Göbeklitepe, SE Anatolia, Turkey: an Example of the Shaping of Cultural Heritage by Local Geology Since the Early Neolithic. Geoheritage 14:57

Ketin İ (1970) Türkiye’de Önemli Jeolojik Aflörmanların Korunması. Türk Jeol Bül 13(2):90–93 (in Turkish)

Kılıç H, Bağcı HR (2020) Bir Jeomorfosit Olarak Karaçay Kanyonu (Çıldır). Jass Stud- J Acad Soc Sci Stud 13(82, Winter):389–410 (in Turkish)

Kıranşan K (2022) Ergani İlçesinin Jeopark Potansiyeli. Bingöl Üniv Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Derg 23(1):226–248 (in Turkish)

Kocalar AC (2020) Latmos Geopark (Beşparmak Mountaıns) Wıth Herakleıalatmos Antıque Harbour Cıty And Bafa Lake Natural Park In Turkey. Turk J Eng 4(4):176–182 (in Turkish)

Kocalar AC (2021) Jeoturizmin Türkiye’deki Potansiyelinin Kırsal Kalkınma Açısından İncelenmesi. Iğdır Üniv İktisadi Ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Derg 6:25–36 (in Turkish)

Koçan N (2011) Kızılcahamam-Çamlıdere Bölgesi’nde (Ankara) Jeolojik Mirasın Korunması. Iğdır Üniv Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Derg 1(4):63–68 (in Turkish)

Koçan N (2012) Kızılcahamam-Çamlıdere jeoparkında kırsal peyzaj ve rekreasyon planlama. Erciyes Üniv Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Fen Bilimleri Derg 28(1):38–46 (in Turkish)

Koçan N (2012) Ekoturizm ve Sürdürülebilir Kalkınma: Kızılcahamam-Çamlıdere (Ankara) Jeopark ve Jeoturizm Projesi. Karadeniz Fen Bilimleri Derg 2(6):69–82 (in Turkish)

Koçan N (2013) Kızılcahamam-Çamlıdere (Ankara) Bölgesi Jeolojik Mirasının Koruma Kullanma Potansiyeli. Kastamonu Üniv Orman Fakültesi Derg 13(1):36–47 (in Turkish)

Koçman A (2004) Yanık ülkenin doğal anıtları: Kula yöresi volkanik oluşumları. Ege Coğrafya Derg 13:5–15 (in Turkish)

Köroğlu F, Kandemir R (2019) Vulnerable geosites of Çayırbağı-Çalköy (Düzköy-Trabzon) in the Eastern Black Sea region of NE Turkey and their geotourism potential. Geoheritage 11(3):1101–1111

Kurt S (2015) The coasts of Kapıdağ peninsula in terms of geomorphotourism. Geojournal Tour Geosites 1(15):44–58 (in Turkish)

Madran E (1996) Cumhuriyet’in İlk Otuz Yılında (1920–1950) Koruma Alanının Örgütlenmesi-I. METU JFA 16(1–2):59–97

Németh K, Moufti MR (2017) Geoheritage values of a mature monogenetic volcanic field in intra-continental settings: Harrat Khaybar, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Geoheritage 9:311–328

Newsome D, Dowling RK (2010) Geotourism: the tourism of geology and landscape. Goodfellow Publishers, Oxford

Neto K, Henriques MH (2022) Geoconservation in Africa: State of the art and future challenges. Gondwana Res 110:107–113

Öngür T (1976) Doğal anıtların korunmasında yasal dayanaklar. Yeryuvarı Ve İnsan 1(4):17–23 (in Turkish)

Özcan A, Aytaş İ (2019) Biyoçeşitlilik Sıcak Noktası ve Jeolojik Miras Alanı Olan Karstik Peyzajların Zamansal Değişimi: Çankırı Jipsli Tepeleri. Yüzüncü Yıl Üniv Tarım Bilimleri Derg 29(4):618–627 ((in Turkish))

Özcan K, Tarakcıo H (2021) Türkiye’de jeolojik mirasın korunması üzerine analitik çerçeve. TÜBA-KED Türk Bilimler Akademisi Kültür Envanteri Derg 24:145–158 (in Turkish)

Özçelik M (2022) Comparison of the environmental impact and production cost rates of aggregates produced from stream deposits and crushed rock quarries (Boğaçay Basin/Antalya/Turkey). Geoheritage 14:18

Özdemir MA (2019) Afyonkarahisar (Seydiler) peribacaları jeomorfositi ve turizm potansiyeli. Uluslararası Sosyal Araştırmalar Derg 12(64):249–262 (in Turkish)

Özer S, Mülayim O (2022) Geoconservation and geotourism potential of vulnerable rudist fossil geosites from SE Anatolia (Turkey). Geoheritage 14:12

Özpay GA (2020) Geotourism and proposed geopark projects in Turkey. In: Nekouie SB (ed) The Geotourism Industry in the 21st Century: The Origin, Principles, and Futuristic Approach, 1st edn. Apple Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429292798

Özpay GA, Erdem-Özgen N, Ayaz E, Ocak F (2017) Yeni Bir Jeoturizm Sahası: Emirhan Kayalıkları (Sivas). SOBİDER (Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi) (14):15–29

Özgeriş M, Karahan F (2021) Use of geopark resource values for a sustainable tourism: a case study from Turkey (Cittaslow Uzundere). Environ Dev Sustain 23:4270–4284

Özkaymak Ç, Yıldız A, Karabaşoğlu A, Bağcı M, Başaran C (2017) Seydiler (Afyonkarahisar) ve Çevresinin Jeoturizm Potansiyelinin Belirlenmesi. Türk Jeol Bül 60:259–282 (in Turkish)

Özşahin E (2013) Yunushanı köyünün (Altınözü Hatay) kuzey ve kuzeybatısındaki peribacası görünümlü sivri doruklu lapya kompleksleri. Turk Stud 8(6):551–566 (in Turkish)

Öztürk A, Horasan BY (2020) Dünyada karstik jeopark turizmi ve jeopark öneri alanı: Karapınar (Konya-Türkiye). Konya Mühendislik Bilimleri Derg 8(4):876–888 (in Turkish)

Patzack M, Eder W (1998) UNESCO Geopark, a new programme– a new UNESCO label. Geol Balc 28(3–4):33–35

ProGeo Group (1998) A first attemt at a geosites framework for European UGS initiative to support recognition of World heritage and European geodiversity. Geol Balc 28:5–32

Prosser CD, Brown EJ, Larwood JG, Bridgland DR (2013) Geoconservation for science and society–an agenda for the future. Proc Geol Assoc 124(4):561–567

Ruban DA (2010) Quantification of geodiversity and its loss. Proc Geol Assoc 121:326–333

Şakar FS (2022) Kapadokya doğal ve kültürel miras alanlarinin koruma ve planlama süreçleri. TUBA-KED: Turkish Academy of Sciences, Journal of Cultural Inventory, 26 (in Turkish)

Selçuk AS, Zorer H (2017) Başkale Bölgesi’nin (Van) Jeolojik ve Jeomorfolojik Öğeleri. Türk Jeol Bül 60(1):1–16 (in Turkish)

Serrano E, Ruis-Flano P (2007) Geodiversity: a theoretical and Applied concept. Geogr Helv 62:140–147

Sinanoğlu D, Siyako M, Karadoğan S, Erdem NÖ (2017) Kültürel Jeoloji Açısından Hasankeyf (Batman) Yerleşmesi. Türk Jeol Bül 60(1):1–14 (in Turkish)

Sinanoğlu D (2018) Eğitsel-Bilimsel Jeositlere Bir Örnek: Garzan Yüzleği. Batman Üniv Yaşam Bilimleri Derg 8(1/2):9–15 (in Turkish)

Solmaz ŞF (2022) Kapadokya doğal ve kültürel miras alanlarının koruma tarihi. TÜBA-KED Türk Bilimler Akademisi Kültür Envanteri Derg 26:11–30 (in Turkish)

Sümer Ö, Akbulut M, İnaner H (2020) New geosite candidates from Urla (İzmir, Western Anatolia, Turkey): a list of geological assets nested with antique and modern cultural heritage. Turk J Earth Sci 29:1017–1032

Şahin GN, Kurul E (2009) A history of the development of conservation measures in Turkey. From the Mid 19th Century Until 2004. METU JFA 26(2):19–44

Şahin G, Balcı-Akova S (2019) Türkiye’nin Coğrafi İşaret Niteliğindeki Jeolojik Değerleri. Asia Minor Stud 7(2):335–354 (in Turkish)

Tekkaya İ (1976) İnsanlara ait fosil ayak izleri. Yeryuvarı ve İnsan 1/2(8–12):195–201 (in Turkish)

Theodossiou-Drandaki I, Nakov R, Wimbledon WAP, Serjani A et al (2004) IUGS Geosites project progress-a first attempt at a common framework list for South Eastern European Countries. In: Parkes MA (ed) Natural and Cultural Landscapes. The Geological Foundation, Royal Irish Academy, Dublin, pp 81–90

TMMOB Jeoloji Mühendisleri Odası (2019) Jeolojik Açıdan Tabiat Varlıkları. Jeolojik Mirasın Önemi ve Türkiye'deki Durum Hakkında Rapor. Yayın No: 137 (in Turkish)

Todorov T, Wimbledon WAP (2004) Geological heritage conservation on international, regional, national, and local levels. Pol Geol Inst Spec Pap 13:9–12

Toprak Ö, Şahin H (2017) Niksar (Tokat) Yöresinin Jeodeğerleri. Türk Jeol Bül 60(1):1–16 (in Turkish)

Turoğlu H (2020) Karasu Grabeni (Hatay, Türkiye) Bazalt Morfolojisinde Volkanik Jeomorfosit Değerlendirmesi. Jeomorfolojik Araştırmalar Derg 4:62–80 (in Turkish)

Uncu L, Karakoca E (2019) Evaluating the Geomorphological Features and Geotourism Potentials of Harmankaya Canyon (Bilecik, Turkey). J Hosp Tour 7(1):1–15 (in Turkish)

Ustaömer PA, Sayın N, Ustaömer T, Görüm T, Hisarlı M (2005) Boyabat Sinop Jeolojik Miras Envanter Çalışması. TÜBA-KED Türk Bilimler Akademisi Kültür Envanteri Derg 6:127–137 (in Turkish)

Uzun A (2017) Bir Açık Alan Dersliği: Kandıra Kıyıları (Kocaeli, Türkiye). Türk Jeol Bül 60(1):1–12 (in Turkish)

Üner S, Alırız MG, Özsayın E, Selçuk AS, Karabıyıkoğlu M (2017) Earthquake induced sedimentary structures (Seismites): Geoconservation and promotion as geological heritage (Lake Van-Turkey). Geoheritage 9(2):133–139

Van Loon AJ (2008) Geological education of the future. Earth Sci Rev 86(1–4):247–254

Wang L, Tian M, Wang L (2015) Geodiversity, geoconservation and geotourism in Hong Kong Global Geopark of China. Proc Geol Assoc 126:426–437

Wimbledon WAP (1996) Geosites-A New Conservation Initiative. Episodes 19:87–88

Wimbledon WAP, Smith-Meyers S (2012) Geoheritage in Europe and its conservation. PeoGEO Spec Pub, Oslo, Norway, p 405

Yakupoğlu T, Özcan SG (2020) Nemrut Kalderası’nın (Bitlis/TÜRKİYE) Jeopark Potansiyeli. Yüzüncü Yıl Üniv Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü Derg 25(1):1–12 (in Turkish)

Yalçın MN, Gürpınar O, Altınok Y, Özer N et al (2004) Buldan (Denizli) Yöresinin Temel Jeolojik Özellikleri ve Jeolojik Miras Envanteri. TÜBA Kültür Envanteri Derg 2:169–186 (in Turkish)

Yalçın MN (2007) TÜBA-TÜKSEK Kültür Kitap Projesi, Yıldız Dağları Yakın Çevresi Tarih Araştırmaları, 22–23 Mayıs, 2006, Kırklareli- Türkiye, Burgaz- Bulgaristan, ss 69–73 (in Turkish)

Yalçın MN (2017) İstanbul’un Kaybolan Değerlerine Farklı Bir Örnek: Jeolojik Miras. Mega Projeler Ve İstanbul 58:18–22

Yalçın MN (2021) Jeolojik miras konusuna tarihsel bir bakış ve gelecek için bazı önermeler. Ed. Selman Er. In Jeolojik Miras-Kavramlar, Mevzuat ve Uygulama Örnekleri. TMMOB Jeoloji Mühendisleri Odası İstanbul Şubesi, ss 3–12 (in Turkish)

Yeşilova C (2021) Potential geoheritage assessment; Dereiçi travertines, Başkale, Van (east anatolian Turkey). MANAS J Eng 9(1):66–71 (in Turkish)

Yetiş AŞ (2022) Kapadokya Bölgesi’nin Jeoturizm Açısından Mevcut Durumunun Belirlenmesi. J Gastronomy Hosp Travel 5(2):702–709 (in Turkish)

Yıldırım T, Koçan N (2008) Nevşehir Acıgöl kalderası Kalecitepe ve Acıgöl maarlarının jeoturizm kapsamında değerlendirilmesi. Ege Üniv Ziraat Fakültesi Derg 45(2):135–143 (in Turkish)

Yıldırım A, Karadoğan S (2010) Derik (Mardin) güneyinde korunması gereken jeolojik jeomorfolojik bir doğal miras: Kuşçu krateri. Dicle Üniv Ziya Gökalp Eğitim Fakültesi Derg 14:119–133 (in Turkish)

Yılmaz A (2002) Jeolojik Mirasımız. TÜBİTAK Bilim ve Teknik Derg 416:92–93 (in Turkish)

Yılmaz A (2002) Jeoparklar. TÜBİTAK Bilim Ve Teknik Derg 417:64–68 (in Turkish)

Yılmaz E (2013) Jeolojik oluşumların kültür varlıkları açısından değerlendirilmesi ve turizme kazandırılması: Pamukkale örneği. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Kültür Varlıkları ve Müzeler Genel Müdürlüğü, pp 159 (in Turkish)

Yüceer H, Baba A, Gönülal YÖ, Uştuk O, Gerçek D, Güler S, Uzelli T (2021) Valuing groundwater heritage: the historic wells of Kadıovacık. Geoheritage 13:97

Yüksel U, Eraslan Ş (2019) Jeolojik Miras Niteliğindeki Doğal Taşların Peyzaj Tasarımında Kullanım Olanakları. J Archit Sci Appl 4(1):69–89 (in Turkish)

Yüksel V, Korkmaz S (1982) Mitoloji, Jeoloji, Jeoturizm: Olimpos’un sönmeyen Alevi. Yeryuvarı Ve İnsan 7(2):3–4 (in Turkish)

Yürür MT, Saein AF, Kaygısız N (2019) What a geologist may do when the geological heritage is in danger? Geoheritage 11(2):301–308

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. We are grateful to Profs. Sacit Özer and İsmail Ömer Yılmaz for their helpful remarks, corrections and comments on the text. Our special thanks to Prof. Dr. Nizamettin Kazancı, who made the first breakthrough on this topic in Türkiye, for his contributions to the development of these issues. In the evaluation processes, anonymous reviewers for their comments and improvements on our manuscript and thank the Editor-in-Chief Kevin Page.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Fatih Köroğlu: original conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, investigation, writing—original draft, visualization, data curation, writing—review and editing. Oğuz Mülayim: investigation, visualization, data curation, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Köroğlu, F., Mülayim, O. Geoconservation Strategies of Türkiye. Geoheritage 15, 97 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-023-00862-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-023-00862-5