Abstract

The aim of the study was to investigate the association between food craving and lifetime number of weight-loss attempts, as a proxy index of difficulties in weight-loss maintenance. The participants were 100 adult out-patients with BMI ≥ 25 admitted at three medical centers for the treatment of obesity and excess weight in Rome (Italy). The patients were administered the State and Trait Food Cravings Questionnaire, trait version (FCQ-T). The patients with five or more weight loss episodes (compared to those with four treatments or less) differed in all the dimensions of the FCQ-T. Food craving is associated with more difficulties in weight-loss maintenance after weight-loss interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity and overeating are widespread conditions caused by multiple and different factors that are spreading exponentially throughout the world. Approximately 1.6 billion adults worldwide were overweight [body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2] and at least 400 million were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) in 2005; in other words, this means that the prevalence of obesity has increased dramatically over the last five decades worldwide, reaching around one-third of the population in the most affected countries with another 30 % being overweight [1].

Weight-loss interventions to correct excess weight and obesity are very frequent, but approximately 20 % of individuals are successful at long-term weight-loss maintenance [2]. Recidivism is high and repetitive loss and regain of body weight is a prevalent phenomenon in the history of obese patients [3].

In the last decades, several researchers have hypothesized some parallelism between addictive behaviors, eating disorders, and obesity [4–6], and introduced the construct of “food addiction”. Food addiction is a chronic and relapsing condition due to the interaction among several variables which increase the craving for specific foods [7] with the aim of gaining a feeling of pleasure and excitement [8].

The parallelism between addictive behaviors and obesity are at the genetic [9] and neurochemical/neuroanatomical [4, 5, 10] levels, and are associated with environmental factors linked to the laws of learning [11]. For example, researchers indicated dysregulation in the brain dopamine pathway of obese patients [4, 5, 10] as earlier evidenced in drug addiction [12].

A second considerable characteristic shared by obesity and addictive disorders is the chronic and relapsing course of the illness [8]. Obese and overweight patients have a history of frequent relapses after weight-loss treatments, which are successful in the short term but appear to be ineffective in the long term [13, 14]. Numerous factors are associated with relapses and difficulties in weight-loss maintenance, for example binge eating, emotional eating, passive coping styles [15], depression and substance abuse [16], and physical inactivity [17].

Furthermore, obese people report greater craving for foods [18, 19], experience more negative affects, and eat arousing foods more frequently than control subjects [8].

Several studies reported an association between food craving (FC; i.e., the intense desire to consume a specific food) and eating disorders, such as bulimia nervosa (BN) [20], anorexia nervosa (AN) [20], binge eating disorder (BED) [21, 22], night eating syndrome (NES) [23], as well as overeating and obesity [19, 24].

Thus, the aim of the study was to investigate the association between food craving and lifetime number of weight-loss treatments in patients who were currently attending a weight-loss program. The lifetime number of weight-loss attempts was used as proxy index of relapses after nutritional treatments. We hypothesized that higher FC is associated with more lifetime weight-loss interventions.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

The participants were 100 consecutive outpatients (27 men and 73 women) who were attending low-energy diet therapy in three medical centers specialized in the treatment of obesity and excess weight in Rome (Italy). All the patients were enrolled between January and May 2011, and voluntarily accepted to participate in the study and signed informed consent. The criteria included an age between 18 and 65 years, and a BMI of 25 or higher. Exclusion criteria were the presence of major disorders of the central nervous system (e.g., epilepsy, dementia, or Parkinson disease), and the presence of any condition affecting the ability to complete the assessment, including the denial of informed consent. The average age of the patients was 40.95 ± 11.92 years (range 18–65 years).

Measures

Socio-demographic and clinical data

Clinical and socio-demographic information was retrieved from medical records by two researchers independently. In cases of disagreement, a third party was consulted. Weight-loss attempts have been defined as specific weight loss periods in which individuals have intentionally engaged in weight-loss programs with the help of physicians or nutritionists [25].

Food craving

Patients were administered the Italian version of the State and Trait Food Cravings Questionnaire, trait version (FCQ-T) [26], a 39-item scale measuring FC. The FCQ-T measures nine dimensions of FC [20]: (1) anticipation of positive reinforcement from eating (ANT+); (2) anticipation of relief of negative states and feelings from eating (ANT−); (3) intentions and plans to consume food (Intent); (4) cues that may trigger food cravings (Cues); (5) thoughts or preoccupation with food (Thoughts); (6) craving as hunger (Hunger); (7) lack of control over eating (Control); (8) emotions that may be experienced before or during food cravings or eating (Emotions); and (9) guilt from cravings and/or for giving into them (Guilt). The scale demonstrated good psychometric properties [20, 27].

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were analyzed with Mann–Whitney U tests for two independent samples for non-normally distributed quasi-dimensional variables, and one-way Fisher exact tests and Chi-squared tests (χ2) for N × N contingency tables. To assess the independent association between groups and each variable significant at the bivariate analyses, while handling for non-normality of predictors, we performed a robust generalized linear model with Newton–Raphson algorithm. Groups were entered as criterion and variables significant at the bivariate analyses as independent variables. All the analyses were performed with the Statistical Package For Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows 17.0.

Results

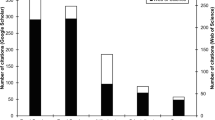

Forty-eight percent of the patients were obese (BMI ≥ 30) and 52 % were overweight (Mean BMI of the patients was 30.58 ± 5.31). Furthermore, 46 % of the patients reported four lifetime weight-loss treatments or less, while 54 % reported five or more lifetime weight-loss treatments. Differences between groups are listed in Table 1. Patients reporting more lifetime weight-loss treatments (compared to those with fewer weight-loss treatments) were more frequently women (87.0 vs. 56.5 %; P < 0.001) and reported higher scores on the FCQ-T (126.31 ± 32.13 vs. 98.28 ± 33.28; U = 640.50; P < 0.001) and in all its dimensions, but they did not differ in their preference for fatty and sweet food in their cravings (4.48 ± 3.22 vs. 3.52 ± 2.28; U = 1,060.50; P = 0.20). Furthermore, groups did not differ in age (40.87 ± 11.62 vs. 41.04 ± 12.39; U = 1,221.50; P = 0.89), and BMI (31.18 ± 5.08 vs. 29.87 ± 5.54; U = 1,006.50; P = 0.10).

To assess the independent association between groups and each variable significant at the bivariate analyses, we performed a robust generalized linear model with groups as criterion and variables as independent variables. The model fitted the data well (Likelihood ratio χ 210 = 36.67; P < 0.001). Groups were independently associated with only three-dimensions of the FCQ-T. Patients with more weight-loss treatments (compared to those with fewer weight-loss treatments) were: (1) 1.2 times more likely to have higher scores on the FCQ-T ANT+ [95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.02/1.41; P < 0.05]; (2) 1.3 times more likely to have lower scores on the FCQ-T Intent (95 % CI 0.60/0.97; P < 0.05); and (3) 1.2 times more likely to have higher scores on the dimension Guilt (95 % CI 1.02/1.50; P < 0.05).

Discussion

The aim of the study was to investigate the association between FC and lifetime number of weight-loss treatments in patients who were currently attending low-energy diet therapy. The results of the study are in line with the hypothesis that FC is associated with more lifetime weight-loss attempts, a proxy index of relapses after weight loss interventions.

These results are consistent with the hypothesis that FC may be linked to more relapses and difficulties in weight-loss maintenance after low energy diets in obese patients, and are also consistent with the hypothesis that conceptualizes obesity as an addictive behavior. In fact, craving is supposed to be a key variable in favoring relapses in patients with substance abuse [28, 29].

Our findings indicate that obese patients reporting more weight-loss treatments have higher anticipation of relief from negative states and feelings derived from eating and have more guilt from cravings, and lower planning in consuming food. These results support the previous literature [16]. The feeling of an urge to eat and the depressive symptoms, associated with guilt after binging, were indicated as risk factors for relapses after weight-loss treatments. Furthermore the result, which indicates that the anticipation of positive reinforcement is linked to the difficulty in maintaining weight-loss, calls into question the reward system, which is implicated in the perception of pleasure and involved in addictive disorders [30, 31]. In the last years, literature has reported numerous alterations in the reward system of individuals suffering from eating disorders, especially obese patients [4–6], but also in patients with BN [32] or BED [33]. The simultaneous presence of high anticipation of positive reinforcement associated with food, and less programming and intent to consume foods are also consistent with the hypothesis of Volkow and colleagues [34] who suggest an implication of the executive functions in obesity.

Nevertheless, the association between FC and weight-loss treatments may be interpreted in the opposite way, i e., relapses following weight-loss treatments may contribute to increase FC, rather than the other way around. Observing diet restrictions might influence FC, although this is a controversial issue [35, 36].

In spite of our interesting results, the study has some noteworthy limitations. Firstly, the sample is limited and the patients were recruited from only three medical centers, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Secondly, we have not assessed patients for psychopathology (for example, mood disorders or eating disorders). Thirdly, we only used self-report measures and the difficulty in weight-loss maintenance was measured indirectly through the lifetime number of weight-loss treatments. Nevertheless, our results have important implications for clinicians. They have to assess FC carefully, given its association with relapses and difficulties in weight-loss maintenance [37], and with binge eating [22], and planning specific treatments for those patients who have higher craving for foods [38–40].

In conclusion, our results seem to support the hypothesis indicating obesity as an addictive behavior, and point out the role of craving in relapses and difficulties in weight-loss maintenance after diet treatments. Therefore, future interventions may benefit from the assessment of FC in order to identify unsuccessful weight-loss maintainers and tailor specific interventions for these patients.

References

Eckardt K, Taube A, Eckel J (2011) Obesity-associated insulin resistance in skeletal muscle: role of lipid accumulation and physical inactivity. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 12:163–172

Wing RR, Hill JO (2001) Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr 21:323–341

Karhunen L, Lyly M, Lapvetelainen A, Kolehmainen M, Laaksonen DE, Lahteenmaki L, Poutanen K (2012) Psychobehavioural factors are more strongly associated with successful weight management than predetermined satiety effect or other characteristics of diet. J Obes 2012:274068

Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Logan J, Pappas NR, Wong CT, Zhu W, Netusil N, Fowler JS (2001) Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancet 357:354–357

Stice E, Yokum S, Blum K, Bohon C (2010) Weight gain is associated with reduced striatal response to palatable food. J Neurosci 30:13105–13109

Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Baler R (2011) Food and drug reward: overlapping circuits in human obesity and addiction. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 11:1–24

White MA, Whisenhunt BL, Williamson DA, Greenway FL, Netemeyer RG (2002) Development and validation of the food-craving inventory. Obes Res 10:107–114

von Deneen KM, Liu Y (2011) Obesity as an addiction: why do the obese eat more? Maturitas 68:342–345

Volkow ND, Wise RA (2005) How can drug addiction help us understand obesity? Nat Neurosci 8:555–560

Gearhardt AN, Yokum S, Orr PT, Stice E, Corbin WR, Brownell KD (2011) Neural correlates of food addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68:808–816

Green MW, Rogers PJ, Elliman NA (2000) Dietary restraint and addictive behaviors: the generalizability of Tiffany’s cue reactivity model. Int J Eat Disord 27:419–427

Blum K, Braverman ER, Holder JM, Lubar JF, Monastra VJ, Miller D, Lubar JO, Chen TJ, Comings DE (2000) Reward deficiency syndrome: a biogenetic model for the diagnosis and treatment of impulsive, addictive, and compulsive behaviors. J Psychoactive Drugs 32(Suppl: i–iv):1–112

Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL, Boucher JL, Histon T, Caplan W, Bowman JD, Pronk NP (2007) Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. J Am Diet Assoc 107:1755–1767

Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, Appel LJ, Hollis JF, Loria CM, Vollmer WM, Gullion CM, Funk K, Smith P, Samuel-Hodge C, Myers V, Lien LF, Laferriere D, Kennedy B, Jerome GJ, Heinith F, Harsha DW, Evans P, Erlinger TP, Dalcin AT, Coughlin J, Charleston J, Champagne CM, Bauck A, Ard JD, Aicher K (2008) Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA 299:1139–1148

Elfhag K, Rossner S (2005) Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev 6:67–85

Odom J, Zalesin KC, Washington TL, Miller WW, Hakmeh B, Zaremba DL, Altattan M, Balasubramaniam M, Gibbs DS, Krause KR, Chengelis DL, Franklin BA, McCullough PA (2010) Behavioral predictors of weight regain after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 20:349–356

Jakicic JM (2009) The effect of physical activity on body weight. Obesity 17(Suppl 3):S34–S38

Pepino MY, Finkbeiner S, Mennella JA (2009) Similarities in food cravings and mood states between obese women and women who smoke tobacco. Obesity 17:1158–1163

Fabbricatore M, Imperatori C, Morgia A, Contardi A, Tamburello S, Tamburello A, Innamorati M (2011) Food craving and personality dimensions in overweight and obese patients attending low energy diet therapy. Obe Metab 7:e28–e34

Moreno S, Rodriguez S, Fernandez MC, Tamez J, Cepeda-Benito A (2008) Clinical validation of the trait and state versions of the Food Craving Questionnaire. Assessment 15:375–387

White MA, Grilo CM (2005) Psychometric properties of the Food Craving Inventory among obese patients with binge eating disorder. Eat Behav 6:239–245

Fabbricatore M, Imperatori C, Pecchioli C, Micarelli T, Contardi A, Tamburello S, Innamorati M, Tamburello A (2011) Binge eating and BIS/BAS activity in obese patients with intense food craving who attend weight control programs. Obe Metab 7:e21–e27

Jarosz PA, Dobal MT, Wilson FL, Schram CA (2007) Disordered eating and food cravings among urban obese African American women. Eat Behav 8:374–381

Vander Wal JS, Johnston KA, Dhurandhar NV (2007) Psychometric properties of the State and Trait Food Cravings Questionnaires among overweight and obese persons. Eat Behav 8:211–223

Wing RR, Phelan S (2005) Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr 82:222S–225S

Cepeda-Benito A, Gleaves DH, Fernandez MC, Vila J, Williams TL, Reynoso J (2000) The development and validation of Spanish versions of the State and Trait Food Cravings Questionnaires. Behav Res Ther 38:1125–1138

Cepeda-Benito A, Fernandez MC, Moreno S (2003) Relationship of gender and eating disorder symptoms to reported cravings for food: construct validation of state and trait craving questionnaires in Spanish. Appetite 40:47–54

Marlatt GA, Gordon JR (1985) Relapse prevention: maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. Guilford Press, New York

Kaplan GB, Heinrichs SC, Carey RJ (2011) Treatment of addiction and anxiety using extinction approaches: neural mechanisms and their treatment implications. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 97:619–625

Wise RA (2009) Roles for nigrostriatal—not just mesocorticolimbic—dopamine in reward and addiction. Trends Neurosci 32:517–524

Hogarth L (2011) The role of impulsivity in the aetiology of drug dependence: reward sensitivity versus automaticity. Psychopharmacology 215:567–580

Penas-Lledo EM, Loeb KL, Martin L, Fan J (2007) Anterior cingulate activity in bulimia nervosa: a fMRI case study. Eat Weight Disord 12:e78–e82

Mathes WF, Brownley KA, Mo X, Bulik CM (2009) The biology of binge eating. Appetite 52:545–553

Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Telang F (2011) Quantification of behavior sackler colloquium: addiction: beyond dopamine reward circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:15037–15042

Coelho JS, Polivy J, Herman CP (2006) Selective carbohydrate or protein restriction: effects on subsequent food intake and cravings. Appetite 47:352–360

Martin CK, O’Neil PM, Tollefson G, Greenway FL, White MA (2008) The association between food cravings and consumption of specific foods in a laboratory taste test. Appetite 51:324–326

Meule A, Lutz A, Vogele C, Kubler A (2012) Food cravings discriminate differentially between successful and unsuccessful dieters and non-dieters. Validation of the Food Cravings Questionnaires in German. Appetite 58:88–97

Budak AR, Thomas SE (2009) Food craving as a predictor of “relapse” in the bariatric surgery population: a review with suggestions. Bariatric Nursing and Surgical Patient Care 4:115–121

Goldman RL, Borckardt JJ, Frohman HA, O’Neil PM, Madan A, Campbell LK, Budak A, George MS (2011) Prefrontal cortex transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) temporarily reduces food cravings and increases the self-reported ability to resist food in adults with frequent food craving. Appetite 56:741–746

Alberts HJ, Mulkens S, Smeets M, Thewissen R (2010) Coping with food cravings. Investigating the potential of a mindfulness-based intervention. Appetite 55:160–163

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Fabbricatore, M., Imperatori, C., Contardi, A. et al. Food craving is associated with multiple weight loss attempts. Mediterr J Nutr Metab 6, 79–83 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12349-012-0115-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12349-012-0115-x