Abstract

The goal of this study is to explore the relationship between students’ self-reported stress and teacher-informed depression, and to determine whether students’ resilience, self-concept, and social skills moderate this relationship. The sample included 481 participants aged 7–10 years, with a total of 252 boys (52.4%) and 229 girls (47.6%). The participants were selected from schools in the Basque country, 59.5% from public schools (n = 286) and 40.5% from private/subsidized schools (n = 195). To measure the variables under study, we requested the teachers to complete a questionnaire on depressive symptomatology for each of their students (CDS-teacher), and the students completed another four assessment tools to evaluate their levels of stress (IECI), their self-concept (CAG), social skills (SSiS), and resilience (RSCA). We found a positive correlation between depression and school stress and a negative one between depression and intellectual self-concept, sense of control, social skills (cooperation and responsibility), and variables that make up resilience (optimism, adaptability, trust, support, and tolerance). We found that self-concept, social skills, and resilience all moderated the relationship between stress and childhood depression. The amount of variance explained in the moderation models obtained ranged from 18 to 76%. The results obtained may be useful for the design of prevention and intervention programs for childhood depression, including strengthening children’s self-concept, social skills, and resilience as protective factors against depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression is the main worldwide cause of health and disability issues, and it affects more than 300 million people worldwide, representing an increase of 18% between 2005 and 2015 (Worldwide Health Organization [WHO], 2017). It is a mental illness that affects people of all ages, but early detection is essential for its prevention. Hence, the importance of identifying depression from an early age and of trying to understand the multiple associated factors. Herman, Reinke, Parkin, Traylor, and Agarwal (2009) underline the main role of the school in the lives of children outside of the family environment, as a place where depression can develop, be prevented, and even be treated.

Regarding the prevalence of childhood depression, the results of studies conducted in school contexts indicate prevalence rates around 4% in Spain or Turkey, 6% in Finland, 8% in Greece, 10% in Australia, and 25% in Colombia (for a review, see Garaigordobil, Bernaras, Jaureguizar, & Machimbarrena, 2017). Although there is discrepancy about teachers’ accuracy when reporting students’ depressive symptoms, Achenbach, McConaughy, and Howell (1987) found statistically significant and moderate correlations between teachers’ reports and students’ self-reports.

Stress has been identified as a very important factor related to depression, as it has been found that stress frequently precedes depression, both in clinical and community samples (see review of Hammen, 2005). However, as pointed out by Hammen (2005), one of the major unknowns still remains unresolved: why do some people suffer depression after a stressful experience and others do not? A resilience-based framework may shed more light on this unresolved question. As explained by Hjemdal, Vogel, Solem, Hagen, and Stiles (2011), taking into account that the development of emotional disorders has been linked to a stress-diathesis hypothesis, resilience may be helpful to better understand it because resilience theory was also founded on the relationship between stress and psychopathology.

Resilience is understood as the capacity or set of features that enables one to adapt successfully to stressful challenges (Alvord & Grados, 2005). Both risk and promotive factors are necessary for resilience: for example, stress would be a risk factor for depression, and coping skills would be promotive factors that help to avoid the negative effect of stress. Fergus and Zimmerman (2005) explain that promotive factors may be either assets (positive factors within the individual, like competence, self-efficacy, or coping skills) or resources (external to the individual, like parental support).

Moreover, three main models of resilience have been proposed: (1) the compensatory model, which explains the direct effect of resilience as a factor that balances out the negative effect of stress; (2) the protective model, which analyzes the buffering effect of resilience in the relationship between stress and its negative effects (like depression), testing moderation effects through multiple regressions or structural equation modeling; and (3) the challenge model, where the relationship between a risk factor and an outcome is curvilinear and must be tested with longitudinal data: low and high levels of risk factors are related to negative outcomes, but moderate levels of risk factors are related to less negative outcomes (Anyan & Hjemdal, 2016; Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). The present study will be based on the protective model and will try to analyze the moderating effect of resilience and related assets, like self-concept and social skills, in the relationship between stress and depression in children.

Previous studies have shown that resilience buffers the impact of stress on depressive symptomatology in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (Anyan, Worsley, & Hjemdal, 2017; Ding, Han, Zhang, Wang, Gong, & Yang, 2017; Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000; Wingo, Wrenn, Pelletier, Gutman, Bradley, & Ressler, 2010). For example, Anyan and Hjemdal (2016) found that resilience moderated the effect of stress on depressive symptoms in adolescents: the simple slope analyses showed that stress was only significantly associated with depression when resilience was low or average, while the effect of stress on depression for adolescents who scored higher in resilience was low and nonsignificant. This means that resilience contributes to reduce the effect of the relationship between stress and depression; thus, interventions directed to reduce the effects of stress on depressive symptomatology should be directed toward adolescents who show lower resilience (lower levels of personal disposition, lower levels of family warmth and coherence, lower social support…).

Nevertheless, further research is needed about the relationship between resilience, stress, and childhood depression in non-clinical sample, because most studies that analyze the buffering effect of resilience on depression focus on adolescence (probably due to the increasing rates of depression during adolescence), and if younger children are analyzed most studies focus on clinical samples that have suffered an adversity. For example, the meta-analysis conducted by Hu, Zhang, and Wang (2015) analyzed 60 studies that examined trait resilience and mental health (depression, anxiety, positive affect, and satisfaction with life) in all age stages and none of them included a sample composed just by children (only two studies included both children and adolescents that had experienced an adversity). Moreover, although frequently the onset of depressive symptomatology is observed at the age of 7 or 8 years (Bernaras, Jaureguizar, Soroa, Ibabe & de las Cuevas, 2013; Whalen et al., 2016), childhood depression is one of the most overlooked psychological disorders (Cicchetti & Toth 1998); therefore, the school seems to play a critical role in its early detection and better understanding (Herman et al., 2009). Thus, further studies developed in school contexts seem to be necessary.

Self-concept has been identified as an asset related to resilience. Self-concept, understood as one’s cognitive appraisal of oneself, based on one’s previous experiences, reinforcement history, and interactions with others (Bracken, 1996), is an important factor in depressive symptomatology and stress coping (Martinsen, Neumer, Holen, Waaktaar, Sund, & Kendall, 2016; Morales, 2017; van Tuijl, de Jong, Sportel, de Hullu, & Nauta, 2014). People with a high self-concept respect themselves and make others respect them, have a greater capacity to adapt and engage in relationships with others, taking on an active role, which increases their self-confidence, and is related to more effective stress-coping strategies and reduces the risk of depression (Fathi-Ashtiani, Ejei, Khodapanahi, & Tarkhorani, 2007; Morales, 2017). Moreover, cognitive vulnerability models (e.g., Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978; Beck, 1967) suggest that negative cognitive styles (like perceived helplessness or a negative self-concept) moderate the relationship between stress and depression; thus, the cognitive style would be a trait-like construct that contributes to the development and maintenance of depressive symptoms in the presence stressors. However, some authors defend that this hypothesis is more consistent in studies with adults than with children (for a review, see Gibb & Coles, 2005), and that the mediational models are more accurate than the moderation models for children and adolescents (Cole, 1990, 1991; Cole & Turner, 1993): stressors like negative life events would contribute to the development of low self-perceived competence, which would contribute vulnerability to depressive symptoms. Thus, the present study analyzes a moderation model in children, due to the inconsistent previous results and the differing theoretical models.

In addition, many studies have linked social skills and depression, but the precise nature of this relationship is not as well understood (Segrin & Flora, 2000) Lewinsohn’s behavioral theory of depression stipulated that depressed people often lack social skills: they are unable to obtain positive reinforcement from the social world where they live and they avoid negative results and get depressed as a result (Lewinsohn, 1974, 1975; Youngren & Lewinsohn, 1980). Nonetheless, these same authors, some years later, explained that lack of social skills could be secondary to being depressed (Lewinsohn, Hoberman, Teri, & Hautzinger, 1985). Nowadays, there is still serious disagreement about the conceptualization and operationalization of social skills, but it seems quite clear that “disrupted social skills are indeed a problem for at least some people with depression” (Segrin, 2000, p. 381).

Based in the diathesis-stress models of psychopathology, Segrin and Flora (2000) suggest that people with poor social skills are more vulnerable to depression when stressed; they may have more difficulties arranging their social support and using effective problem-solving strategies. On the contrary, people who suffer stress but have strong social skills will be resilient and less vulnerable to depression. Social skills like being communicative, inspiring confidence, or feeling empathy, are relevant factors associated with resilience because they facilitate receiving help and more opportunities (Masten, 1994) and are associated with reduction of depression and anxiety (Sancassiani et al., 2015). Moreover, this social competence gets relevance from early childhood, because it is critical for the overall child well-being, undergirds other areas of development and predicts future social and emotional competencies (see review by Darling-Churchill & Lippman 2016). Nilsen, Karevold, Røysamb, Gustavson, and Mathiesen (2013) suggest that “being socially skilled in early adolescence is important for subsequent supportive relations with friends, parents, and teachers and for preventing the development of depressive symptoms” (p. 18). Previous studies with young adults have found that social skills moderate the positive association between depression and stress (Segrin & Flora, 2000; Segrin & Rynes, 2009). Thus, Segrin and Flora (2000) developed a longitudinal study with 118 high school seniors planning to attend the university, and found that particularly strong social skills played a protective role, reducing the strength of the relationship between stress and depression. On the contrary, the relationship between stress and depression was higher between those participants who showed poor or moderate social skills. Nevertheless, no previous studies have been found that seek the moderating effect of social skills on the relationship between stress and child depression, although findings show that social stress (understood as the stress that suffer children in social interactions) is one of the most noteworthy predictor variables of child depression in 8–12-year-old children (Bernaras et al., 2013). Primary school years are of great relevance, because during this period children’s development of personality and social features gains importance, and positive social skills in this stages are associated with social skills during adolescence and adulthood (Karatas, Sag, & Arslan, 2015). Thus, if we can understand the role of the social skills in the relationship between stress and depression in prompt stages, the earlier we will be able to implement prevention and intervention programs to promote social and emotional competence in elementary schools (see Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill, & Abbott, 2008).

Taking into account the results of previous studies, the main goal of this study is to explore the relationship between self-reported stress and teacher-informed depression, based on the hypothesis that resilience, self-concept, and social skills (all self-reported) will have a moderating effect on the stress–depression relationship. No other study testing these moderators simultaneously has been found; moreover, the multi-informant method used, including teacher reports, is another relevant contribution of the study. As explained by Hu, Zhang, and Wang (2015) in their meta-analysis about resilience and mental health, the assessment of mental health should include both negative and positive indicators, and both are considered in the present study (depressive symptomatology and characteristics incompatible with depression).

It is especially important to examine potential moderators that are malleable, as this may help provide direction for intervention development. The present study focuses on the study of resilience, self-concept, and social skills—which are malleable, as proven by several studies and intervention programs (Chmitorz et al., 2018; Haynes & Comer 1990; Masten, 2001; Sancassiani et al., 2015)—as moderators of the relationship between stress and childhood depression.

Method

Participants

The sample was made up of 481 participants, aged from 7 to 10 years, 58.6% were between 7 and 8 years old (n = 282), and 41.4% were between 9 and 10 (n = 199), with a total of 252 boys (52.4%) and 229 girls (47.6%). Participants were selected from schools in the Basque country (Spain), 59.5% from public schools (n = 286) and 40.5% from private/subsidized schools (n = 195). The students were enrolled in third (n = 252, 52.4%) and fourth grade (n = 229, 47.6%) of Primary Education. Of the entire sample, 83.6% (n = 402) were born in the Basque Country, 1.7% (n = 8) in other Spanish provinces, 5.2% were foreigners (n = 25), and 9.6% (n = 46) did not answer this question. The sample was selected intentionally from the schools of Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia, taking into account the balance between public and private/subsidized schools. A large percentage (85.9%) of students consented to participate. Participants were not compensated for this study. A report with the general results of the study was presented to the schools that participated.

Assessment Instruments

To measure the variables under study, we requested the teachers to complete a questionnaire on each of their students (CDS-teacher), while the students completed another four assessment tools to evaluate their stress levels, self-concept, social skills, and resilience (see Table 1).

Procedure

The study used a correlational, predictive, and cross-sectional design. Firstly, a letter was sent to the selected schools, explaining the research project. With the headmasters who agreed to participate, we scheduled an interview in which we explained the project in more detail, and we handed out informed consent forms for parents and/or legal guardians. The members of the research team went to the schools and administered 4 assessment instruments to the participants, in two 40-min assessment sessions, on successive days. In addition, the teacher filled in another instrument with regard to each child. The study met the ethical values required in research with humans and received the favorable report of the Commission of Research Ethics of the University of the Basque Country (CEISH/266MR/2014).

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted in three phases. Firstly, the percentiles for the raw scores of the stress and depression scales were calculated in order to analyze the descriptive statistics of these measures. For the CDS-T scale, in the Total Depressive variable, raw scores of 21 (90th to 95th percentile) indicated a moderate depressive symptomatology, and scores > 21 (96th to 100th percentile) were considered as clinically significant symptomatology. As for the Total Positive variable, raw scores of 9 (10th to 5th percentile) were categorized as moderate depressive symptomatology, and scores < 9 (4th to 1st percentile) as clinically significant symptomatology. These cutoffs were previously validated in another study (Jaureguizar, Bernaras & Garaigordobil, 2017) and were coherent with the cutoffs obtained in the present study. Similarly, the percentiles for the raw score of the IECI scale were calculated, categorizing as moderate stress raw scores between 9 and 11(90th to 95th percentile), and as clinically significant stress raw scores > 11 (96th to 100th percentile), cutoffs previously validated (Machimbarrena, 2017).

In the second phase, we calculated the matrix of bivariate correlations (Pearson’s r) between the variables of depression, which would subsequently be used as dependent variables, and the remaining variables of the study (stress, self-concept, social skills, and resilience).

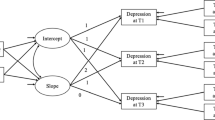

In the third phase, we tested the hypotheses of moderation, such that self-concept, social skills, and resilience would moderate the relationship between stress (independent variable) and depression (dependent variable). Bearing in mind that the stress measurement was made up of three components (health, school, and family stress) and that the moderator variables were also multifactorial, these moderation analyses were conducted through structural equation models (SEMs). We followed the method of Ping (1995) to carry out the analyses. This method involves the use of a single observed dependent variable, a latent variable that includes the indicators that make up the independent variables, another latent variable (correlated with the previous one) that contains the indicators of the moderator variable, and a third latent variable (not correlated with the former ones) that contains an indicator which is the product of the indicators of the independent variable and the indicators of the moderator variable. This indicator, which represents the interaction term of the moderation, is created by multiplying the sum of the scores of the indicators of the dependent variable by the sum of the indicators of the moderator variable. Prior to all the calculations, all the indicators of the independent and moderator variables were centered through conversion to Z-scores.

For a more detailed explanation of the theoretical and mathematical foundations of this and other methods to perform moderation analysis through SEM, we recommend consulting Cortina, Chen, and Dunlap (2001).

The results of the SEM analysis were first appraised through the fit of the different models tested. The following fit indexes were calculated for this purpose: as a fit index of parsimony, the ratio between Χ2 and the degrees of freedom of the model, whose value must be less than 5 to be considered a good fit (Wheaton, Muthén, Alwill, & Summers, 1977). As an absolute index, the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), whose value must be less than .08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993), and as an incremental index, the comparative fit index (CFI), whose value must be greater than .90 (Bentler & Bonnet, 1980). Furthermore, the amount of variance of the dependent variable explained by the predictor, the moderator, and their interaction was also analyzed (R2). The moderation effect was analyzed through the significance of the interaction term between the independent variable and the moderator, as well as the significance of the slopes of the moderation effect. Finally, in order to facilitate comprehension of the moderation results, these were plotted. Then, each one of the significant moderation effects was represented in a separate figure. The figures represent the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable at two different levels of the independent variable (low and high stress) and three levels of the moderator, 1 standard deviation below the mean, and 1 standard deviation above the mean (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

First, separate groups of students were identified depending on their level of depression or stress: thus, on the one hand, the percentage of students with moderate depressive and stress symptomatology, and on the other hand, the percentage with clinically significant depressive symptomatology and stress problems was analyzed. The results showed that in the Total Depressive variable of the CDS-T scale, 32 participants (6.6%) showed moderate depressive symptomatology according to their teachers, and 22 (4.5%) showed clinically significant depressive symptomatology. As for the Total Positive variable, 35 participants (7.3%) had moderate depressive symptomatology, and 45 (9.3%) had clinically significant depressive symptomatology. Moreover, 49 (10.2%) students showed moderate stress problems on the IECI scale, and 15 (3.11%) showed clinically significant stress problems.

Second, we calculated the correlation matrix of the dependent variable (teacher-reported depression) with the independent variables (stress) and moderators (self-concept, social skills, and resilience). The results can be seen in Table 2. As can be seen, depression correlated with stress (specifically, with school stress), self-concept (specifically, with intellectual self-concept and the feeling of control), social skills (in particular, with cooperation and responsibility), and resilience and the variables that conform it (optimism, adaptability, trust, support, and tolerance). The correlations found were in the expected direction: that is, the greater the depression (Total Depressive), the more school stress, lower self-concept, fewer social skills, and lower resilience, and vice versa (with Total Positive).

Then, moderation analyses were carried out. The three indicators of stress (health, school, and family stress) were grouped into a latent variable that served as an independent variable. This latent variable showed a good reliability value according to the construct reliability index (ρ = .63), considering that it is composed of only three indicators. Moreover, the three indicators were significantly and moderately to strongly related to the latent variable: health stress (γ = .67, ε = .74), school stress (γ = .73, ε = .68), and family stress (γ = .57, ε = .82). In turn, each moderator variable (self-concept, social skills, and resilience) was grouped into respective latent variables. Finally, the depression variables (Total Depressive and Total Positive) were introduced one by one in each model, as explained in the section on data analysis. In this way, six moderation models were computed. The results can be seen in Table 3. As can be seen, all the models had satisfactory fit according to the calculated parsimony index and comparative index and, in most cases, also according to the absolute index. There were only two models in which the RMSEA index slightly exceeded the established cutoff point. However, after a general assessment of the indexes, as the other two indexes fell within the limits, we considered the fit satisfactory in all cases. The amount of variance explained in the models ranged from 18 to 76%. Moderation was statistically significant in five of the six models obtained.

In order to facilitate comprehension of the different significant moderator effects found, these results are represented graphically. Effects related to self-concept can be seen in Figs. 1 and 2. Regarding Fig. 1, the post hoc interaction probing tests showed that people with high self-concept showed lower levels of depression in low-stress situations than in high-stress situations [θ = 0.83, t(471) = 2.77, p = .006], but in the case of people with low self-concept, the amount of depression was similar in both high-stress and low-stress situations [θ = − 0.21, ns]. Regarding Fig. 2, post hoc tests showed that people with low self-concept had fewer behaviors incompatible with depression in high-stress situations than in low-stress situations [θ = − 0.44, t(471) = − 3.11, p = .002]. However, in the case of people with high self-concept the amount of behaviors incompatible with depression were similar in both high-stress and low-stress situations [θ = 0.02, ns].

Figures 3 and 4 graphically show the significant results obtained in relation to social skills. There is evidence that people with high social skills show fewer depressive behaviors in low-stress situations than in high-stress situations [θ = 0.77, t(470) = 3.85, p < .001], whereas people with low social skills show similar levels of depressive behavior regardless of the stress experienced [θ = − 0.03, ns]. Finally, considering behaviors that are incompatible with depression (Total Positive), we observed that people with high social skills showed similar levels of positive behavior regardless of the level of stress [θ = 0.03, ns]. In the case of people with low social skills, we observed significantly lower levels of positive behaviors in high-stress situations than in people with high social skills [θ = − 0.43, t (470) = − 4.10, p < .001]. Therefore, social skills are associated with an increase in positive behaviors that protect one even in situations of high stress.

Finally, the only significant effect obtained with the moderator variable resilience showed that people who scored high in resilience performed a greater number of behaviors that are incompatible with depression in high-stress situations than did people with low resilience [θ = − 0.40, t(470) = − 6.33, p < .001]. On the contrary, when stress was low, attitudes incompatible with depression were similar in people with high and low resilience [θ = 0.12, ns] (See Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the relationship between stress and depression in boys and girls aged from 7 ro 10 years, and to delve into the role played by resilience, self-concept, and social skills in the stress–depression relationship. Therefore, it was considered that the school context could be the ideal scenario, due to its importance in children’s development (cognitive and social), and because the teachers can play an important role in the detection and prevention of depressive symptoms. Thus, this study is of a multi-informant nature, involving the teachers in the detection of depressive symptomatology.

The results show that depression (detected by teachers) correlated positively with stress perceived by students, and particularly with school stress. The results are consistent, as students who feel more anxious about school issues are also the ones who, in the teachers’ opinion, show more depressive symptoms. But, not all the students suffering from stress present depressive symptoms. What differentiates those who do not have depressive symptoms from those who do? That is precisely the goal of the present study, to analyze the moderator role of different variables: resilience, social skills, and self-concept. However, the current empirical design is cross-sectional, and causality cannot be concluded. Therefore, the results will be explained in terms of relationships.

Regarding self-concept, we noted that it moderates the relationship between stress and depression, as high self-concept is related to lower levels of depression even in cases with high stress, so it could be a protective factor. In fact, it is linked to positive behaviors both in high- and low-stress situations. In contrast, people with low self-concept have fewer resources to deal with depression in stressful situations, along the lines of the findings of other authors (Martinsen et al., 2016; van Tuijl et al., 2014). In the present study, moreover, intellectual self-concept achieves special importance, as it correlates positively with attitudes that are incompatible with depression (detected by teachers) and negatively with depressive symptoms (reported by teachers). Thus, students who show more depressive traits, according to the teachers’ perception, also have lower intellectual self-concept. Hence, the importance of the school context and of paying special attention to the students’ perceptions of their own intellectual qualities.

On another hand, social skills have also been shown to have a moderator effect on the stress–depression relationship, in the line of previous studies (Segrin & Flora, 2000; Segrin & Rynes, 2009), as having high social skills is associated with an increase in positive behaviors (incompatible with depression) that could buffer negative aspects of stressful situations. These results are especially interesting for the design of programs to prevent depression from an early age.

The reported findings underscore the importance of promoting positive emotions, cognitions, and attitudes to provide children with tools of empowerment so they can cope adequately with stress and not become depressed. In fact, in the present study, it was found that resilience especially buffers the effects of high-stress situations on depression, as more resilient people show more positive behaviors in these situations than people with low resilience, along the findings of Anyan and Hjemdal (2016), who found that the effect of the relationship between stress and depressive symptoms is reduced for adolescents with higher levels of resilience. In conclusion, and in line with a resilience framework, high levels of resilience, social skills, and self-concept would buffer the effects of stress on depression and would facilitate behaviors that are incompatible with depression in high-stress situation.

The present study has some strengths and limitations. One of the main limitations of the study is the lack of self-report data about child depression. In future studies, it would be very interesting to compare the results from self-report assessment instruments and the results from assessment by other informants such as teachers and parents. Nevertheless, it is important to note that CDS-T is a well-established instrument to assess depressive symptomatology.

The intentional selection of the sample is another limitation. Therefore, future studies should use representative samples, and could for instance, compare clinical and non-clinical sample.

The cross-sectional design of the study is another limitation of the present study, so that we cannot establish causal relationships between the variables. Future research could include longitudinal studies in order to better understand the developmental factors associated with the relationship between stress and depression.

Lastly, another limitation that should be mentioned is related to measurement: although the cutoffs used in the present study have been previously validated in other studies, using measures that use normative comparisons, as opposed to criterion-related cutoffs, opens up problems with comparing different samples.

Among its strengths, we include the multi-informant methodology used, which adds richness to the study. Another strong point refers to focusing not only on the “negative” facet of depression (depressive symptoms), but also on the “positive” side (positive behaviors incompatible with depression), as their identification has allowed us to design moderation models in which we see the positive effect of the studied variables, as they reinforce the positive behaviors that protect one from depression in stressful situations. All this allowed us to identify a number of factors that should be included in programs for the prevention and treatment of depression and in programs to learn to cope with stress.

And, finally, we note that the analysis used has allowed us to go a little beyond the relationship between stress and depression, and better understand the factors involved in this complex relationship.

References

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., & Teasdale, J. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.87.1.49.

Achenbach, T. M., McConaughy, S. H., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.213.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Alvord, M., & Grados, J. (2005). Enhancing resilience in children: A proactive approach. Professional Psychology, 36, 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.3.238.

Anyan, F., & Hjemdal, O. (2016). Adolescent stress and symptoms of anxiety and depression: Resilience explains and differentiates the relationships. Journal of Affective Disorders, 203, 213–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.031.

Anyan, F., Worsley, L., & Hjemdal, O. (2017). Anxiety symptoms mediate the relationship between exposure to stressful negative life events and depressive symptoms: A conditional process modelling of the protective effects of resilience. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 29, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2017.04.019.

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonnet, D. G. (1980). Significance test and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588.

Bernaras, E., Jaureguizar, J., Soroa, M., Ibabe, I., & de las Cuevas, C. (2013). Evaluación de la sintomatología depresiva en el contexto escolar y variables asociadas [Evaluation of depressive symptomatology and the related variables in the school context]. Anales de Psicología, 29, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.1.137831.

Bracken, B. A. (Ed.). (1996). Handbook of self-concept: Development, social and clinical considerations. New York, NY: Wiley.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing fit. In K. A. Bollen (Ed.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Chmitorz, A., Kunzler, A., Helmreich, I., Tüscher, O., Kalisch, R., Kubiak, T., et al. (2018). Intervention studies to foster resilience—A systematic review and proposal for resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 78–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.002.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. (1998). The development of depression in children and adolescents. American Psychologist, 53, 221–241.

Cole, D. A. (1990). Relation of social and academic competence to depressive symptoms in childhood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 422–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.99.4.422.

Cole, D. A. (1991). Preliminary support for a competency-based model of depression in children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.2.181.

Cole, D. A., & Turner, J. E. (1993). Models of cognitive mediation and moderation in child depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.102.2.271.

Cortina, J. M., Chen, G., & Dunlap, W. P. (2001). Testing interaction effects in LISREL: Examination and illustration of available procedures. Organizational Research Methods, 4(4), 324–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810144002.

Darling-Churchill, K. E., & Lippman, L. (2016). Early childhood social and emotional development: Advancing the field of measurement. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 45, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.02.002.

Ding, H., Han, J., Zhang, M., Wang, K., Gong, J., & Yang, S. (2017). Moderating and mediating effects of resilience between childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in Chinese children. Journal of Affective Disorders, 211, 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.056.

Fathi-Ashtiani, A., Ejei, J., Khodapanahi, M. K., & Tarkhorani, H. (2007). Relationship between self-concept, self-esteem, anxiety, depression and academic achievement in adolescents. Journal of Applied Sciences, 7, 995–1000.

Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357.

Garaigordobil, M., Bernaras, E., Jaureguizar, J., & Machimbarrena, J. M. (2017). Childhood depression: Relation to adaptive, clinical and predictor variables. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 821. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00821.

García, B. (2001). CAG: Cuestionario de Autoconcepto: Manual [Self-Concept Questionnaire: Hanbook]. Madrid: EOS.

Gibb, B. E., & Coles, M. E. (2005). Cognitive vulnerability-stress models of psychopathology: A developmental perspective. In B. L. Hankin & J. R. Z. Abela (Eds.), Development of psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective (pp. 104–135). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gresham, F. M., & Elliott, S. N. (2008). Social skills improvement system rating scales manual. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson.

Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 293–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938.

Hawkins, J. D., Kosterman, R., Catalano, R. F., Hill, K. G., & Abbott, R. D. (2008). Effects of social development intervention in childhood 15 years later. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 162, 1133–1141. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.162.12.1133.

Haynes, N. M., & Comer, J. P. (1990). The effects of school development program on self-concept. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 63, 275–283.

Herman, K. C., Reinke, W. M., Parkin, J., Traylor, K. B., & Agarwal, G. (2009). Childhood depression: Rethinking the role of the school. Psychology in the Schools, 46, 433–446. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20388.

Hjemdal, O., Vogel, P. A., Solem, S., Hagen, K., & Stiles, T. C. (2011). The relationship between resilience and levels of anxiety, depression and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in adolescents. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18, 314–321. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.719.

Hu, T., Zhang, D., & Wang, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.039.

Jaureguizar, J., Bernaras, E., & Garaigordobil, M. (2017). Child depression: Prevalence and comparison between self-reports and teacher reports. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 20(e17), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2017.14.

Karatas, Z., Sag, R., & Arslan, D. (2015). Development of social skill rating scale for primary school students-teacher form (SSRS-T) and analysis of its psychometric properties. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197, 1447–1453.

Lang, M., & Tisher M. (2004). Children’s Depression Scale, third research edition. Camberbell, Victoria, Australia: Australian Council for Educational Research. (update of the test of M. Lang and M. Tisher (1983). Children’s Depression Scale).

Lewinsohn, P. M. (1974). A behavioral approach to depression. In R. J. Friedman & M. M. Katz (Eds.), The psychology of depression: Contemporary theory and research (pp. 157–185). Washington, DC: Winston-Wiley.

Lewinsohn, P. M. (1975). The behavioral study and treatment of depression. In M. Hersen, R. M. Eisler, & P. M. Miller (Eds.), Progress in behavior modification (Vol. 1, pp. 19–64). New York: Academic Press.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Hoberman, H., Teri, L., & Hautzinger, M. (1985). An integrative theory of depression. In S. Reiss & R. R. Bootzin (Eds.), Theoretical issues in behavior therapy (pp. 331–359). New York: Academic Press.

Luthar, S., & Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 857–885. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400004156.

Machimbarrena, J. M. (2017). Bullying & Cyberbullying: prevalence in the last stage of primary school and connections with personal and family variables. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Faculty of Psychology, University of the Basque Country, Spain.

Martinsen, K. D., Neumer, S. P., Holen, S., Waaktaar, T., Sund, A. M., & Kendall, P. C. (2016). Self-reported quality of life and self-esteem in sad and anxious school children. BMC Psychology, 13(4(1)), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0153-0.

Masten, A. S. (1994). Resilience in individual development: Successful adaptation despite risk and adversity. In M. C. Wang & E. W. Gordon (Eds.), Educational resilience in inner-city America: Challenges and prospects (pp. 3–25). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56, 227–238.

Morales, F. M. (2017). Relationship between coping with daily stress, self-concept, social skills and emotional intelligence. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 10, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejeps.2017.04.001.

Nilsen, W., Karevold, E., Røysamb, E., Gustavson, K., & Mathiesen, K. S. (2013). Social skills and depressive symptoms across adolescence: Social support as a mediator in girls versus boys. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.08.005.

Ping, R. A. (1995). A parsimonious estimating technique for interaction and quadratic latent variables. Journal of Marketing Research, 32, 336–347. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151985.

Prince-Embury, S. (2008). Resiliency scales for children & adolescents (RSCA). San Antonio: Pearson.

Sancassiani, F., Pintus, E., Holte, A., Paulus, P., Moro, M. F., Cossu, G., et al. (2015). Enhancing the emotional and social skills of the youth to promote their wellbeing and positive development: A systematic review of universal school-based randomized controlled trials. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 11(Suppl. 1: M2), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901511010021.

Segrin, C. (2000). Social skills deficits associated with depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 379–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00104-4.

Segrin, C., & Flora, J. (2000). Poor social skills are a vulnerability factor in the development of psychosocial problems. Human Communication Research, 26, 489–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2000.tb00766.x.

Segrin, C., & Rynes, K. (2009). The mediating role of positive relations with others in associations between depressive symptoms, social skills, and perceived stress. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 962–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.05.012.

Tisher, M. (1995). Teachers’ assessments of prepubertal childhood depression. Australian Journal of Psychology, 47(2), 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049539508257506.

Trianes, M. V., Blanca, M. J., Fernández-Baena, F. J., Escobar, M., & Maldonado, E. F. (2011). IECI. Inventario de estrés cotidiano infantil [Inventory of daily stress in children]. Madrid: TEA.

van Tuijl, L. A., de Jong, P. J., Sportel, B., de Hullu, E., & Nauta, M. H. (2014). Implicit and explicit self-esteem and their reciprocal relationship with symptoms of depression and social anxiety: A longitudinal study in adolescents. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 45, 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.09.007.

Whalen, D. J., Luby, J. L., Tilman, R., Mike, A., Barch, D., & Belden, A. C. (2016). Latent class profiles of depressive symptoms from early to middle childhood: Predictors, outcomes, and gender effects. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57, 794–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12518.

Wheaton, B., Muthén, B., Alwil, D., & Summers, G. (1977). Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. In D. R. Heise (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 84–136). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

WHO. World Health Organization (2017). Depression tops list of causes of ill health. Downloaded from http://www.who.int/campaigns/world-health-day/2017/es/.

Wingo, A. P., Wrenn, G., Pelletier, T., Gutman, A. R., Bradley, B., & Ressler, K. J. (2010). Moderating effects of resilience on depression in individuals with a history of childhood abuse or trauma exposure. Journal of Affective Disorders, 126, 411–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.009.

Youngren, M. A., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (1980). The functional relation between depression and problematic interpersonal behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 89, 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.89.3.333.

Funding

This study was funded by Alicia Koplowitz Foundation, with Grant No. FP15/62. The Alicia Koplowitz Foundation had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaureguizar, J., Garaigordobil, M. & Bernaras, E. Self-concept, Social Skills, and Resilience as Moderators of the Relationship Between Stress and Childhood Depression. School Mental Health 10, 488–499 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9268-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9268-1