Abstract

This study aims to measure the impact on the reputation of corporations and NGOs through their involvement in cause-related marketing campaigns. Quantitative findings enable us to examine two great central ideas regarding the background and consequences of this alliance. First, in terms of goals, perception of the success of the campaign is precisely due to the participation of the NGO as a committed social organization rather than the contribution of the corporation which, in the current CSR paradigm, is challenged to carry out action campaigns in the community. Second, in terms of the actors’ reputation, the corporation obtains higher capitalization from the cause-related marketing campaign than the NGO. In other words, corporations benefit enormously from the image of NGOs to whom it is associated and gives support. Regarding the achievement of its social aim, it is perceived as very good by the community, resulting in an increase in corporate reputation that is distinctly superior to the reputation benefits obtained by the participating NGO.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

At present, Latin America is providing evidence of a growing number of alliances between non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and corporations to carry out cause-related marketing campaigns within the framework of social responsibility, environmental care, and business ethics. These mainly respond to the need of corporations to enhance their reputation, which has been gaining great relevance in recent years, as these types of campaigns help them generate greater credibility across objective target audiences. (Medina 2014).

In Argentina, year after year, the Consejo Publicitario Argentino 2017 (Argentine Advertising Council, in English) launches the call for a contest which rewards communication campaigns for the public good carried out by corporations and NGOs promoting values and generating a positive impact on society. Some of the topics covered in the cases selected this year are, among others, bullying, gender equality, coexistence, solidarity, fight against poverty, education, carefor the environment and animal species, recovery of lost children, integration, and health care. The winners were selected from a total of 106 cases presented in different categories, a record in number of registrations compared to the latest editions.

Valor Martínez and Merino de Diego (2008) postulate that, from a qualitative perspective, two types of forces are contingent on the dynamics of the approach-distance relationship between corporations and NGOs: centripetal and centrifugal. The former, centripetal forces, arise fromthe conditions of the macro environment that encourages and favors collaboration between corporations and NGOs anddeterminespotential collaboration agreementsamong which we find a) the progressive abandonment of the State of its social responsibility by dereliction of duties b) boosting of corporate social responsibility (CSR) which conferscorporationsa greater rolethrough different initiatives, dialogue forums that bring NGOs and corporations closer together, c) the internationalization of corporations,due to globalization, which compelsfirms to face the challenges of the communities in which they operate, d) social movements which are better organized and interconnected which demand greater commitmentfrom corporations and the State in the development of coherent communities with principles of sustainable development and finally, e) the rise of a segment ofsmart consumers. The latter, centrifugal forces,give insight into the distance between NGOs and corporations. In this case, it implies the corporations’ approach that differs from that of the NGOs, their mission, goals and strategies since there are NGOs which assign themselves a morecharitable rolewhile others a more political one. What distances both is the corporations’ denial of the political role of NGOs acknowledging only those that have a more distinguishedcharitablegoal.

Barroso Méndez et al. (2013) argue that the success of the relationship between corporations and NGOs is linked to shared values (Macmillan et al. 2005) which generate trust and commitment between the parties (Morgan and Hunt 1994), willingness for shared learning (Selnes and Sallis 2003) and cooperation (Anderson and Narus 1990) towards catalyzing value, economic and social, and the fulfillment of goals sought by both: reputation, corporate and social.

In large twentieth century corporations, the perspective of CSR emerged as an evolution of corporate philanthropy. It is a new conception of the role and business actions in the development of society based on the triple bottom line approach: economic, social and environmental (Foretica Report 2018). This countinvolves meeting the demands of this generation without jeopardizing the capacity of future generations (Brundtland Commission, UN 1987). In this sense, it can be defined as “the acknowledgement and integration of social and environmental concerns, by corporations’ operations, hence, giving rise to business practices that address these concerns and configure their relationships with their partners” (De la Cuesta and Valor 2003, p. 11), in which the different interest groups which participate in the business activity (stakeholders)create greater value for society (Fundación Ecología y Desarrollo 2004). Thus, corporations are called to overcome globalization without solidarity which negatively affects the poorest sectors. It is not simply about “the phenomenon of exploitation and oppression, but about something new: social exclusion. With it, the idea of belonging to the society in which you live is affected at its very roots, since you are no longer below, on the periphery or without power, but you are outside. The excluded are not only exploited but they are also discarded and disposable”, state the Latin American bishops in Aparecida, Brazil (Aristizábal 2013).

From civil society, in the absence of an active State and in response to political, economic, social and environmental injustices the so-called “Third Sector” emerged, formed by non-profit organizations (NGOs). These organizations tackle diverse social causes with different strategies for the development of funds and resources to fulfill their goals ranging from the search for funds from individual donors, business collaboration (alliances), and access to public funds to international cooperation. Through agreements with corporations, they participate in cause-marketing actions(at a relational level) that are defined as a CSR initiative, which consists of an agreement between a corporation and an NGO to collaborate on a social cause and obtain, in this way, a mutual benefit.

Galán Ladero and Galera Casquet (2014) based on Santesmases (1999) and Kotler and Lee (2005) point out that the company’s commitment focuses on contributing to the cause (financially or in kind) based on the sales or the use of the product. This implies that the final donation will result from the level of consumers’ purchases. According to these authors, these cause-related marketing or business collaboration programs come into sight when a series of simultaneous circumstances converges over time: 1) the emergence of greater consumer awareness of ethical issues, 2) the corporations’ endorsement of the CSR concept and 3) the need for new sources of funding for NGOs due to the growing number of “new” organizations and cuts in public aid or state withdrawal in favor of the private sector.

Consumers appear as almost passive actors, and they are often ignored since they are considered a mere recipient of corporation promises. However, they are gaining more prominence and becoming more aware of their role as consumer-citizens (Cortina 2002; Cortina and Contreras 2003). This position revolves around the concept of “consumer citizenship” which refers to the fact that we are all citizens and citizenship also entails consumer issues. It proposes a liberating consumption and,for this purpose, it is argued that we must beaware of why products are consumed; which are the motivations, and how to escape from the tyranny of consumption.In addition, it establishes the need for fairer consumption and a style of consumption with co-responsibility that has to be worked together with associations, institutions and social groups (Bianchi et al. 2014a). This awareness should be expressed in concrete actions of concrete change: energy saving, water care, concern for others, among other actions which consider ethical, social and ecological dimensions (Bianchi et al. 2014b).

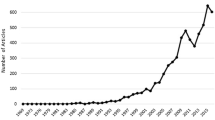

Within this framework, the present study aims to provide expertise in the impact on both NGOs andcorporations reputation in alliances for marketing campaigns; especially, measurement of the variation of NGOs and corporations reputation according to consumer perception ofcause-related marketing campaigns in which both are seen as allies. The article first reviews the literature on the perception of corporate social responsibility, the image of NGOs and its impact on the reputation of both corporations and social organizations; and consumerperception on alliances for cause- related marketing. Then, there is a section on research methodology, a section onfindings and, finally, the conclusions and limitations and some lines of future research. (Fig. 1).

2 Literature review

2.1 The perception of corporate social responsibility and corporate reputation

Regarding consumers’ perception of CSR practices (CSRP) in the Spanish market, the Informe de Forética (Forética Report) 2018 indicates that 76.7% spontaneously know about the phenomenon of social responsibility, 48% claim to adopt life habits with a positive impact on society and that 39% of the featuresof the perception of a good corporationare related to its management of social and environmental aspects. On the other hand, responsible consumption has experienced a rise in the last 3 years, with an increase in both positive and negative actions,

“68.5% of consumers state they have stopped purchasing a product or service based on CSR aspects, which represents a significant leapof 44.6% in the 2014 edition. From the point of view of positive action, 89% of respondents state that, between two identical products, they would purchase the most responsible. 63.9%, from among this group, would be willing to pay a higher price while the remaining 25% would materialize their preference only on equal prices”(Informe Forética 2018, p.22).

While some studies have shown that the influence of CSR information on purchase intention is not relevant (Carrigan and Attalla 2001; Bigné et al. 2005), others haverevealed that information on social responsibility has a positive influence on this behavior (Brown and Dacin 1997; Fernández and Merino Castelló 2005).

According to Kotler and Lee (2013), there are six types of CSR practices or initiatives: corporate cause promotion, cause-related marketing, corporate social marketing, corporate philanthropy, community volunteering, and socially responsible business practices. Focusing on consumers, acknowledging CSR practices seems to have a positive influence on attitudes towards corporations (Brown and Dacin 1997), and their image and reputation (Fombrun and Shanley 1990). Consumers expect organizations to becoherent with social values. Thus, appraisal of the choices they are offered can be based on the fact that the organization acts coherently with the community and society’s welfare (Forte and Lamont 1998).

Corporate reputation is a social construct (Barnett et al. 2006) and is considered a significant aspect of organizational strategy due to the influence of reputation on perceived organizational effectiveness (Mitchell 2015) and, consequently, on resource attraction (Padanyi and Gainer 2003). Corporate reputation is understood as “the perception of the manner in which the corporation behaves with its stakeholders and the degree of information transparency the corporation has with them” (De la Fuente and De Quevedo 2003, p. 281). It is, in a way, the cognitive signal that is a source of external information that acts on consumers’responses and future intentions (Kim and Lennon 2013). A corporation cannot earn a good reputation without first obtaining approval from its stakeholders through corporate communication or reports submissions (King and Whetten 2008). Therefore, the achievement of legitimacy is essential for corporations and it is a prerequisite for corporate reputation management, according to Pérez et al. (2014). The media play an important role in shaping or eroding corporations’ legitimacy: the media can influence corporate reputation and, in doing so, exert pressure on corporations to report or communicate more intensely on their CSR activities (Cormier and Magnan 2003). Corporate reputation constitutes an intangible asset based on the corporate information obtained by interest groups and its ability to meet their expectations. It is, in addition,a resource that is scarce and difficult to imitate (Barney 1991; García Rodríguez 2002), andwhose acquirement is the result of a strongpath (Hall 1993).

Alvarado and Schlesinger (2008) confirm previous studies that view CSR as a multidimensional concept and demonstrate that it playsa role as an antecedent variable of corporate image and reputation.

-

Hypothesis 1: “The perception of corporate responsibility has a positive effect on corporate reputation”

2.2 The image perception of NGOs and the impact on their reputation

Image is concerned with the knowledge, feeling, and beliefs about an organization that exist in the mind of its audience (Hatch and Schultz 1997). Image is also the set of meanings through which people know, describe, remember and relate to an organization (Dowling 1986) and the mental interpretation of an entity (Bennett and Gabriel 2003). Images are developed by means of perception, experience, mental constructions and memory (Costa 2003).

Image captures consumers’ mental representations of an organization and transcends beyond reputation and identity (Bennett and Gabriel 2003; Keller 1993; Schmitt 2012). Brand image influences the attitude of individuals and impacts donation behaviors in the context of nonprofits. Brand image was being conceptualized and measured within the nonprofit context by different authors (Bennett and Sargeant 2005; Bennett and Gabriel 2003; Michel and Rieunier 2012).

Bennett and Sargeant (2005) argue that an excellent charity image influences consumer preferences towards charity brands, helps to increase donations and creates halo effects in relation to other charity activities.

Bennett and Gabriel (2003) conceptualise nonprofit brand image to include five dimensions such as dynamic, idealistic, compassionate, nonpolitical and beneficiaries-oriented. Empirical evidence demonstrates, however, that these nonprofit brand image dimensions only weakly predict intentions to donate (e.g. Sargeant et al. 2008; Venable et al. 2005). For Michel and Rieunier (2012) conceptualization of brand image in nonprofit context consists of four dimensions: useful, efficient, affective, and dynamic, and demonstrate greater impact on donations, in terms of both time and money (Sargeant et al. 2008; Venable et al. 2005).

Brand image can serve to differentiate the roles of functional and symbolic associations of the brand. While functional associations refer to the characteristics of the organization, its mission and tangible qualities, symbolic associations are abstract cognitions that translate the values of the organization, personality traits associated with it and even emotions. (Michel and Rieunier 2012). Since donations of time are more compromising than money donations, the decision-making process can differ. Donations of time procure greater satisfaction than donations of money, being the latter more of a rational rather than emotional decision (Liu and Aaker 2008). The emotional dimensions of nonprofit brands are more likely to exert a stronger influence on intentions to donate time than functional dimensions do (Michel and Rieunier 2012).

Reputation is a concept related to, but different from image. Many times image is confused with reputation; in fact, reputation is a consequence of image as argued by Alvarado and Schlesinger (2008). Whereas image reflects what a firm stands for, reputation reflects how well it has done in the marketplace (Weiss et al. 1999).

An NGO’s reputation is a critical determinant of its authority and ability to act independently or collaboratively to influence global politics. The reputations of NGOs, and how those reputations are derived and constructed, deserve greater attention (Mitchell and Stroup 2017). Those NGOs that are recognized as authorities can help set policy agendas, change actors’ preferences, or mobilize new constituents for political action (Avant et al. 2010).

Del-Castillo-Feito et al. (2019) demonstrate that image is an antecedent of reputation in the context of Spanish public university. Regarding the image and reputation of non-profit organizations, the following hypothesis is proposed:

-

Hypothesis 2: “The image of the NGO has a positive effect on the reputation of the NGO.”

2.3 The perception of the association processes (alliances) between corporations and NGOs for developingcause-related marketing programs

The two most representative types of CSR activities are namely cause promotion and cause-related marketing (Jeon and An 2019; Chéron et al. 2012). Cause promotion is one of CRS activities which intends to increase a level of awareness of a cause and to stimulate consumers´ voluntary participation in supporting it (Kotler and Lee 2005). On the other hand, cause-related marketing draws attention and consumer support for a cause through revenue-producing transactions (Varadarajan and Menon 1988).

Corporations usually make alliances with NGOs to promote mutual interests in both products and services offered and in the public perception of their legitimacy (Kircova and Gürce 2019). The goal (and result) of high-level business NGOs collaborations is to “create groundbreaking social innovations” (Austin and Seitanidi 2012a, p.743). The typology of business-NGO collaboration agreements includes different alternatives, such as corporate philanthropy, licensing, sponsorship, cause-related marketing activities, joint advertising campaigns or joint ventures (Wymer and Samu 2003).

This association of NGOs with corporations in cause-related marketing campaigns soothes potential consumers and boosts a positive attitude towards these campaigns since they are likely to think that corporations only seek to profit from a “good cause” to sell more, to get a whitewashing, to output low quality products or to position itself as environmentally friendly (Galán Ladero and Galera Casquet 2014).

When corporation want to create value by leveraging the gains in reputation, legitimacy and consumers’ trust that they achieve through this kind of alliances it can improve consumer attitudes and have a positive effect on the firms’ financial performance (Carroll and Shabana 2010).

Pérez et al. (2014) assert that interactions between corporations and NGOs are generating relationship models that combine imitation, cooperation, and competition. The result is that new forms of collaboration are emerging which go beyond the mere roles of “donor” and “beneficiary” traditionally adopted in their relationships by both corporations and NGOs. In this new context, alliances can generate different kinds of value to the NGO (Austin and Seitanidi 2012b), including not only the traditional “associative” value (greater visibility, credibility, public notoriety of the social cause) or “transfer” (financial support, in-kind donations, volunteering, etc.), but also other higher-level value types, such as “interaction” value (learning opportunities, development of unique competences, network access, etc.) or “synergy” value (innovation, shared leadership, etc.).

Many of the benefits of cause related marketing, such as increased sales, customer retention, employee or customer loyalty, reduced price sensitivity, enhanced corporate image and reputation, reinforce the idea that organizations might do well by doing good (Deshpande and Hitchon 2002). Alliance can generate positive media coverage, build a reputation of compassion and caring for company, enhance its integrity, enhance employees’ motivation and productivity, consumers’ preferences, positive attitudes, and trust (Duncan and Moriarty 1998). Moreover, when a corporation wants to create value by leveraging the gains in reputation, legitimacy and consumers’ trust that they achieve through this kind of alliances, it can improve consumer attitudes and have a positive effect on the firms’ financial performance (Carroll and Shabana 2010).

The campaign’s perception of success will depend on the values and consumers’ attitude towards corporations’ cause-related marketing, commitment, involvement, and credibility. Consumers are able to identify the goals that led the NGO and the corporation to form an association or alliance to develop a specific cause-related marketing campaign: these goals stem from a prestige nature (visibility, esteem, social value), corporate (loyalty, differentiation, profitability) or social (motivating, helping).

-

Hypothesis 3: “The perception of corporate responsibility has a direct and positive effect on the perception of success of the alliance or cause-related marketing campaign (coherence of objectives)”.

-

Hypothesis 4: “The image of the NGO has a direct and positive effect on the perception of success of the alliance or cause-related marketing campaign (coherence of objectives)”.

In turn, if consumers perceive that those goals are coherent, noble, and clear, the campaign will be successful for them, and therefore they will be inclined to advocate for it, disseminate it, participate, and ultimately generate an increase in the perceived reputation of both participating entities- the corporation and the NGO.

Taking into account all the previous arguments and what it is stated in section 2.1 and in section 2.2, we might propose the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 5: “The perception of success of the alliance or cause-related marketing campaign (coherence of objectives) has a direct and positive effect on corporate reputation”.

-

Hypothesis 6: “The perception of success of the alliance or cause-related marketing campaign (coherence of objectives) has a direct and positive effect on the reputation of the NGO”.

The following figure shows the relationship model of the proposed hypotheses:

3 Research methodology

3.1 Research design

This study is of a quantitative exploratory nature based on the cause-related marketing campaigns carried out in 2015which are of greater recollection by citizens. As a previous task, a list of campaigns-alliances between NGOs and Corporations was crafted on the basis of consultations with experts and professionals working in the field of the third sector together with an exhaustive websearch process, identifying the name of the campaign, corporation and beneficiary NGO. Some 26 relevant campaigns developed in Argentina in 2015, carried out by 15 NGOs and 22 corporations were identified (See Appedix Table 7). Once the lists were refined, they were tested with a small group. It should be remembered that the NGO universe is very diverse, committed to different social causes, of diverse ages and sizes, in which not all NGOs have access to business collaboration to develop these programs (Bianchi et al. 2015).

The population under study was residents over 18 from the city of Córdoba. Non-probabilistic sampling was designed by sex and age quota, the total number of cases being 400, and the final sample after the data purification being 360 cases. The field research was undertaken during September and October 2015. The technical data sheet of the research is shown in Table 1.

A semi-structured questionnaire was devisedin which respondents were first asked to identify those campaigns they had seen, and participating corporations and NGOs. Then, they were asked to mention the one they liked the most. The rest of the questionnaire was developed based on that campaign, and consistedof several sections to measure: the Image of the NGO, reputation, perception of the campaign’s goals, attitude towards cause-related marketing, perception of CSR actions, corporate reputation and consumer identification with the actors and the campaign itself. The profile of the resulting sample is detailed in Table 2.

3.2 Variable measurement scale

The following table illustrates the sources of the measurement scales used. Appedix Table 8 shows the items of the scales used in thisresearch.

To validate the scales and the theoretical model, the two-stage methodological steps proposed by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) were followed to validate multi-attribute measures. In the first stage, the measurement scales are validated by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the robust maximum- likelihood estimation through the EQS. 6.1 software (Bentler 1995). In the second stage, all measurement scales are validated together with the relationships that arise from the model. Since the calculated Mardia’s coefficient is 57.46, a robust estimate is used in order to overcome problems of non-normal data. (Table 3).

Findings of the measurement scales’ validation process illustrated in Table 4 indicate a correct approach to the measurement scales given that a) the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is greater than 0.8 or very close to it –NGO’s Image and Perception of the Alliance scale; b) the composite reliability index (CRI) is greater than 0.7 (Bagozzi et al. 1991; Hair Jr. et al. 1999) and c) the average variance extracted (AVE) which estimates the amount of variance captured by the measure of a construct in relation to the random measurement error, has values greater than 0.5 in all cases or closer as in the case of the above- mentioned scales.

Convergent validity exists if the criteria for convergent validity of a measurement scale are met (Malhotra and Birks 2007; Sánchez Sarabia 1999), which are a) the goodness of fit of the measurement model, b) the Lagrange Multiplier test and c) the significance and direction of factor loadings of the items and the averages of the standardized factor loadings on each factor. The robust fit statistic (Χ2Satorra–Bentler (109) = 191.93 p = 0.000) is significant due to the effect of the sample size, with very good indicators of goodness of fit since they are above the recommended critical value of 0,90(BBNFI = 0.911 and the GFI = 0.959) and the residuals are less than 0.05 (RMSR = 0.046). Regarding factor loadings, the average is expected to be greater than 0.7, which is approximated in all cases, except in the RSCP scale with an average factor loading value of 0.661; a contrast of Student’s t.

Among the discriminant validity criteria (Churchill Jr 1979; Sánchez Sarabia 1999; Vila López et al. 2000; Uriel and Aldás 2005) we find a) the chi-square difference test, b) the confidence interval and c) the average variance extracted. The first one compares the goodness of fit of two models, the one of initial measurement with the one in which covariance is assumed equal to one to the pair of factors that indicates the highest correlation. In our case, Image of NGOs with NGOs Reputation whose Value is 0.664. In thisinstance, the difference between the two amounts to 94,537 with a degree of freedom, which is significantlyhigher than the critical chi-square value of 10,827 for p < 0.001, and consequently the scale measurement model is better where factors areseen as different. The confidence interval test entails verifying that the value one is not included in - + 2 standard errors of the correlation between factors (Vila López et al. 2000; Anderson and Gerbing 1988). From Table 5 it can be seen that of all confidence intervals calculated for each of the pairs of factors none include the unit, so the discriminant validity of the scales is also guaranteed by this criterion. Finally, the extracted variance test consists of comparing the EVT of each of the factors studied with the square of the correlations of each pair of factors, being whether the EVT of the two factors are higher than the square of its correlation the criterion to assert discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981; Vila López et al. 2000), which is also true.

4 Results

Table 6 shows the standardized coefficients of the relationships of the structural relationships model contrasted with their associated t-value as well as the corresponding hypothesis contrast.

We applied the robust maximum likelihood (RML) method, which is suitable for solving non-normality issues of the data, since the estimated Mardia’s coefficient is 57,46. This method uses, in the model fit, the statistical scaling of Satorra–Bentler χ2 (S-B χ2) (Satorra and Bentler 1994), which is sensitive to the sample size and multivariate normality deviations, and it therefore tends to be significant (Bentler and Bonnett 1980). Considering that, literature suggests that the statistic is acceptable if the coefficient between S-B χ2 and the degrees of freedom is lower than 5 (Wheaton et al. 1977), completing the evaluation of the model with other measures of goodness of fit (Hair et al. 2005; Hu and Bentler 1999), being the fit indicators those reported by Eqs. 6.1 software (BBNFI = 0.949 and CFI = 0.949, RMSEA = 0.051). Based on these arguments, the adjustment of the measurement model is good (see Table 6).

On the other hand, the Lagrange multiplier test does not suggest the inclusion of new structural relationships between the variables or latent factors studied, which makes it possible to assert that the proposed theoretical model is valid.

The structural relationships established in the six hypotheses are significant at a level of p < 0.001 for H2, H4, H5 y H6 and at a level of p < 0.01 for H1 and H3, so its rejection is not possible and consequently, they have all been accepted.

First, the acceptance of the H1 hypothesis confirms the presumption that the perception of CSR actions influence corporate reputation since it is significant in statistical terms (p < 0.01) even though it has a magnitude of less importance than expected (0.184), even if we compare the H2 hypothesis which confirms the strong relationship between the Image of the NGO and its Reputation (0.504; p < 0.001).

Second, Hypotheses H2 and H3have been demonstrated indicating in both cases the direct and positive relationship of the perception of Corporate Responsibility and the Image of the NGO on the Perception of the success of the cause-related marketing campaign (alliance). Nevertheless, the Image of NGOs (0.297; p < 0.001)is of greater magnitude and of greater statistical significance than the Perception of CSR (0.226; p < 0.01).

Third, the perception of success of the alliance or cause-marketing campaign (coherence of objective) reveals a direct and positive impact on corporate reputation and on the reputation of the NGO’s, being of greater magnitude in Corporate Reputation (0.586; p < 0.001) than in the Reputation of the NGO (0.383; p < 0.001), which confirms hypotheses H5 and H6.

Finally, if we consider the overall effect achieved by participant actors, we can appreciatethat in both cases they have benefited from the alliance that gives rise to the cause-related marketing campaign,being the overall effect of the PCRS on corporate reputation of 0.316 (direct effect = 0.184 + indirect effect = 0.132) and in the case of the Image of the NGO in its Reputation of 0.618 (direct effect = 0.505 + indirecteffect = 0.114). The indirect effect illustrates the contribution of having participated in the alliance, beingmore relevant for the Corporation, in which it contributes to a 42% impact on corporate reputation, than for the NGO,in which it scarcely contributes 18%.

5 Conclusions: Limitations andlinesof future research

In order to contribute to the line of work that investigates the desirability of partnerships between NGOs and corporations within the framework of CSR and the urge to meet social needs, we pursued the aimto measure the impact on the reputation of the NGO and the corporation in cause-related marketing campaigns in which both participate.

Findings of this research enable us to observe two great central ideas about the background and consequences of the alliance.Regarding the first, it is demonstrated that the reasonbehindthe perception of success of the campaign in terms of goals (greater acceptance of actions in the community, customer and donor loyalty, increased resources for NGOs) is precisely due to the NGO. Consumers seethe NGO, rather than the corporation, as contributinglargely as a committed social organization to a cause which, in the current CSR paradigm, is challenged by social actors to carry out action campaigns in the community. This statement is in line with what Galán Ladero and Galera Casquet (2014) mention regarding the consumer when they indicate that what makes them have a positive attitude towards these campaigns is the presence of the NGO since they mistrust corporations’intentions.

Regarding the second, in terms of actor reputation,it is evident that the greatest capitalization of the cause-related marketing campaignis made by the corporation on the NGO. Corporations benefitenormously from the image of NGOs with which they are associated. In addition, their contribution is perceived as very good by the community in general because of the support they provideto a social organization committed to a cause, thus bringing benefits in their recipients. NGOsare not perceived as seeking greater reputation per se, but seeking other goals, such as obtainingmore resources.This is so because their reputation is more strongly linkedto the image achieved by being dynamic, innovative, advanced in its field and close to its ultimate goal for which they exist.

The above-mentioned statement leads us to assert that NGOs are involved in these cause-relatedmarketing campaigns because of other types of goals which go beyond prestige, other category of values Austin and Seitanidi (2012a) consider: the “associative” (greater visibility, credibility, public notoriety of the social cause), “transfer” (financial support, donations in- kind, volunteering, etc.), “interaction” (learning opportunities, development of unique skills, access to networks, etc.) or “synergy” value (innovation, shared leadership, etc.).

These statements enable us to draw some implications ofrelevance for the management of both actors. Ifwe consider that corporationshave doubts about the benefit theyobtain from CSR actions and the credibility perceived by consumers and the community, astheir final interest lies in maintaining orstrengthening their reputation in society, it has now been demonstrated that the plan of action with thegreatest impact is to carry out such CSR actions in partnership with NGOs whichproject a good image in society. As regardsNGOs, what they achieve is notso much capitalization in terms of reputation, but other goals and needs such as the opportunity to raise more funds or the achievement of greater visibility to the extent that such campaigns entailsignificant public exposure in the main national media.

Findings of this study should be qualified according to a series of limitations inherent to them from which conclusions should be read. First, the sample of campaigns recognized by consumers is small compared to the total number of campaigns that are carried out and involve larger NGOs with well-kwoncorporationsfrom the media, mass consumption and financial institutions sectors. Second, the geographical scope is confined to just one city in the Argentine Republic, which does not represent the totality and restricts the generalization of the conclusions drawnin this study. Third, consumers’ appraised the most recalled and favorite campaign, being the choice of appraised NGO and corporation a subjective selection of participants. Finally, it should be noted that the PCRS Scale is, according to the literature, a second-order scale, and this research prioritizesappraisals on visible and perceptive aspects by consumers such as actions towards the community and on clients, and dismissesevaluative aspects related to other stakeholders such as employees, NGOs, legal compliance with the State etc.to act on the model as a one-dimensional scale.

Research findings, conclusions and limitations suggest the need to explore new lines of research. In the first place, to deepen the impacts that joint participation in cause-related marketing campaigns has on participant actors based on whichgoalsthey pursue that, in the case of NGOs, are very diverse as indicated: visibility, notoriety, credibility, etc. Second, to consider that perception on CSR actions ismultidimensional. Third, it would be interesting to contrast the model against different types of responsible consumers or consumer identification with corporations and NGOs or different reasons or causes supported byconsumers. Finally, in order to enable the generalization of the model illustrated hereit would also be necessary to make a contrast with different geographical contexts and economic situations through the replication of the present study in order to enable the generalization of the modelillustrated here.

References

Alvarado, H. A., & Schlesinger, G. M. W. (2008). Dimensionalidad de la responsabilidad social corporativa percibida y sus efectos sobre la imagen y la reputación: una aproximación desde el modelo de Carroll. EstudiosGerenciales, 24(108), 37–59.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Anderson, J. C., & Narus, J. A. (1990). A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. Journal of Marketing, 54, 42–58.

Aristizábal, J. D. G. (2013). El pecado como deshumanización en el documento de aparecida/Sin as Dehumanization in the Aparecida Document/O pecado como desumanização no documento de aparecida. CuestionesTeológicas, 40(94), 433.

Austin, J. E., & Seitanidi, M. M. (2012a). Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses: Part I. value creation spectrum and collaboration stages. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(5), 726–758.

Austin, J. E., & Seitanidi, M. M. (2012b). Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses. Part 2: Partnership processes and outcomes. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(6), 929–968.

Avant, D. D., Finnemore, M., & Sell, S. K. (2010). Whogovernstheglobe? New York: Cambridge UniversityPress.

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Singh, S. (1991). On the use of structural equation models in experimental designs: Two extensions. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 8(2), 125–140.

Barnett, M. L., Jermier, J. M., & Lafferty, B. A. (2006). Corporate reputation: The definitional landscape. Corporate Reputation Review, 9(1), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550012.

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17, 99–110.

Barroso Méndez, M. J, Galera Casquet, C. y Valero Amaro, V. (2013) Alianzas entre Empresas y Ongs en el ámbito de la RSC: proposición de un modelo de éxito, Aemark 2013. http://www.aemark.es/XXV-CONGRESO-AEMARK-2013.zip. Accessed 25 Sept 2017.

Barroso Méndez, M. J, Galera Casquet, C., Valero Amaro, V., & Galán Ladero, M. M. (2015). Diseño y validación de una escala para medir el éxito de procesos de Asociación entre Empresas y Ongd, Aemark 2015. http://www.aemarkcongresos.com/congreso2015/PDF/9788416462513%20XXVII%20Congreso%20AEMARK%202015.pdf. Accessed 25 Sept 2017.

Bennett, R., & Gabriel, H. (2003). Image and reputational characteristics of UK charitable organizations: An empirical study. Corporate Reputation Review, 6(3), 276–289.

Bennett, R., & Sargeant, A. (2005). Thenonprofit marketing landscape: Guest editors' introduction to a special section. Journal of Business Research, 58(6), 797–805.

Bentler, P. M. (1995). EQS structural equations program manual. Los Angeles: Multivariate Software, Inc..

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606.

Berens, G., & Van Riel, C. B. (2004). Corporate associations in the academic literature: Three main streams of thought in the reputation measurement literature. Corporate Reputation Review, 7(2), 161–178.

Bianchi, E., Carmelé, B., Tubaro, D., & Bruno, J. M. (2014a). Conciencia y acciones de consumo responsable en los jóvenes universitarios. Escritos Contables y de Administración, 4(1), 81–107.

Bianchi, E., Ferreyra, S., & de Gesualdo, G. K. (2014b). Consumo responsable: diagnóstico y análisis comparativo en la Argentina y Uruguay. Escritos Contables y de Administración, 4(1), 43–79.

Bianchi, E., Gracia Daponte, G., Bruno, J., & Giorgis, M. (2015) Los vínculos de cooperación entre las ONG y empresas para el fortalecimiento institucional en el marco de la Responsabilidad Social (RSE), XXIX Encuentro de Docentes de Comercialización de Argentina y América Latina, 17 al 19 de Septiembre de 2015.

Bigné, E., & Currás Pérez, R. (2008). ¿Influye la imagen de responsabilidad social en la intención de compra? El papel de la identificación del consumidor con la empresa. Universia Business Review, 19, 10–23.

Bigné, E., Chumpitaz, R., Andreu, L., & Swaen, V. (2005). Percepción de la responsabilidad social corporativa: un análisis cross-cultural. Universia Business Review, (5) Primer Trimestre, 14-27.

Bigné, E., Alvarado, A., Aldás, J., & Currás, R. (2011). Efectos de la responsabilidad social corporativa percibida por el consumidor sobre el valor y la satisfacción con el servicio. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 20(4), 139–160.

Brown, T., & Dacin, P. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61, 68–84.

Carrigan, M., & Attalla, A. (2001). The myth of the ethical consumer: Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(7), 560–577.

Carroll, A. B., & Shabana, K. M. (2010). The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International journal of management reviews, 12(1), 85–105.

Chéron, E., Kohlbacher, F., & Kusuma, K. (2012). The effects of brand-cause fit and campaign duration on consumer perception of cause-related marketing in Japan. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 29(5), 357–368.

Chun, R. (2005). Corporate reputation: Meaning and measurement. International Journal of Management Reviews, 7(2), 91–109.

Churchill Jr., G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73.

Consejo Publicitario Argentino. (2017) http://www.consejopublicitario.org. Accessed 25 September 2017.

Cormier, D., & Magnan, M. (2003). Environmental reporting management: A continental European perspective. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 22, 43–62.

Cortina, A. (2002). Por una ética del consumo. Madrid: Taurus.

Cortina, A., & Contreras, I. (2003). Consumo…luego existo. Cuaderno de Cristianisme i Justícia 123, Barcelona.

Costa, J. (2003). Creación de la imagen corporativa, el paradigma del siglo XXI. Razón y Palabra, 34(8), 1–15.

Davies, G., Chun, R., da Silva, R. V., & Roper, S. (2001). The personification metaphor as a measurement approach for corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 4(2), 113–127.

De la Cuesta, M. y Valor, C. (2003) Responsabilidad social de la empresa. Concepto, medición y desarrollo en España. Boletín Económico del ICE, 2755, 7–19.

De La Fuente, J. M., & De Quevedo, E. (2003). The concept and measurement of corporate reputation: An application to Spanish financial intermediaries. Corporate Reputation Review, 5(4), 280–301.

Del-Castillo-Feito, C., Blanco-González, A., & González-Vázquez, E. (2019). The relationship between image and reputation in the Spanish public university. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 25(2), 87–92.

Deshpande, S., & Hitchon, J. C. (2002). Cause-related marketing ads in the light of negative news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 79(4), 905–926.

Dowling, G. R. (1986). Managing your corporate images. Industrial Marketing Management, 15(2), 109–115.

Duncan, T., & Moriarty, S. E. (1998). A communication-based marketing model for managing relationships. Journal of marketing, 62(2), 1–13.

Fernández, D., & Merino Castelló, A. (2005). ¿Existe disponibilidad a pagar por responsabilidad social corporativa? Percepción de los consumidores. Universia Business Review, (7)Tercer Trimestre, p. 38-53.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What's in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258.

Forética Report. (2018). Sobre la evolución de la RSE y Sostenibilidad. La recompensa del optimista. https://www.foretica.org/informe_foretica_2018.pdf. Accessed 5 Octuber 2019.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388.

Forte, M., & Lamont, B. T. (1998). The bottom line effects of greening: Implications of environmental awareness. Academy of Management, 12(1), 89–90.

Fundación Ecología y Desarrollo. (2004). Anuario sobre Responsabilidad Social Corporativa en España 2003 http://www.ecodes.org/documentos/archivo/anuarioRSC.pdf. Accessed 25 Sept 2017.

Galán Ladero, M., & Galera Casquet, C. G. (2014). Marketing con causa. Evidencias prácticas desde la perspectiva del consumidor (1401). Catedra Fundación Ramón Areces de Distribución Comercial. https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/ovrdocfra/1401.htm. Accessed 25 Sept 2017.

García Rodríguez, F. J. (2002). La reputación como recurso estratégico: un enfoque de recursos y capacidades [tesis doctoral]. Universidad de La Laguna.

Hair, J. Jr., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1999). Análisis Multivariante, Editorial Prentice Hall.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., & Tatham, R. (2005). Multivariate Data Analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Hall, R. (1993). A framework linking intangibles resources and capabilities to sustainable competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 607–618.

Hatch, M. J., & Schultz, M. (1997). Relations between organizational culture, identity and image. European Journal of Marketing, 31(5–6), 356–365.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria vs new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Jeon, M. A., & An, D. (2019). A study on the relationship between perceived CSR motives, authenticity and company attitudes: A comparative analysis of cause promotion and cause-related marketing. Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility, 4(1), 7.

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22.

Kim, J., & Lennon, S. J. (2013). Effects of reputation and website quality on online consumers' emotion, perceived risk and purchase intention: Based on the stimulus-organism-response model. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 7(1), 33–56.

King, B. G., & Whetten, D. A. (2008). Rethinking the relationship between reputation and legitimacy: A social actor conceptualization. Corporate Reputation Review, 11(3), 192–207.

Kircova, I., & Gürce, M. Y. (2019). Non-profit Foundation and Brand Alliances as a Reputation Management. Ethics, Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Marketing, 158.

Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2005). Corporate Social Responsibility: Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause. Inc, Toronto: John Wiley&Sons.

Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2013). Good works: Marketing and corporate initiative that build a better world and the bottom line. Hoboken: Wiley.

Liu, W., & Aaker, J. (2008). The happiness of giving: The time-ask effect. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 543–557.

Macmillan, K., Money, K., Money, A., & Downing, S. (2005). Relationship Marketing in the not-for-Profit Sector: An extension and application of the commitment-trust theory. Journal of Business Research, 58, 806–818.

Malhotra, N. K., & Birks, D. F. (2007). Marketing research: an applied approach (3rd European ed.). Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Marín, L., & Ruiz, S. (2008). La evaluación de la empresa por el consumidor según sus acciones de RSC. Cuadernos de Economía y Dirección de la Empresa, 11(35), 91–112.

Medina, A. (2014). Mejora tu reputación con una campaña social. ¿Qué tan difícil es desarrollar una Campaña social? Una experta te comparte sus claves para retribuir a la sociedad y mejorar la reputación de tu marca, Alto Nivel, México. www.altonivel.com.mx/43554-mejora-tu-reputacion-con-una-campana-social.html. Accessed 1 July 2017.

Michel, G., & Rieunier, S. (2012). Nonprofit brand image and typicality influences on charitable giving. Journal of Business Research, 65(5), 701–707.

Mitchell, G. E. (2015). The attributes of effective NGOs and the leadership values associated with a reputation for organizational effectiveness. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 26(1), 39–57.

Mitchell, G. E., & Stroup, S. S. (2017). The reputations of NGOs: Peer evaluations of effectiveness. The Review of International Organizations, 12(3), 397–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-016-9259-7.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(July), 20–38.

Padanyi, P., & Gainer, B. (2003). Peer reputation in the nonprofit sector: Its role in nonprofit sector management. Corporate Reputation Review, 6(3), 252–265. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540204.

Pérez, S., Álvarez González, L., & Rey García, M. (2014). La innovación social como resultado de los acuerdos decooperación empresa-organización no lucrativa, Aemark 2014. http://www.aemarkcongresos.com/congreso2014/videos/aemark-actas-2014.pdf. Accessed 25 Sept 2017.

Sánchez Sarabia, F. (1999). Metodología para la investigación de mercado y Dirección de Empresas. Madrid: Ediciones Pirámide.

Santesmases M. M. (1999): Marketing. Conceptos y Estrategias. 4ª edición. Pirámide, Madrid.

Sargeant, A., Hudson, J., & West, D. C. (2008). Conceptualizing brand values in the charity sector the relationship between sector, cause and organization. Service Industries Journal, 28(5), 615–632.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis.

Schmitt, B. (2012). The consumer psychology of brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(1), 7–17.

Selnes, F., & Sallis, J. (2003). Promoting relationship learning. Journal of Marketing, 67(3), 80–95.

Uriel, E., & Aldás M. J. A. (2005). Análisis Multivariante Aplicado. Thomson. España.

Valor Martínez, C., & Merino de Diego, A. (2008) La relación pública entre empresas y ONG. Análisis de su impacto en la elaboración de políticas públicas en el marco de la RSE, CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa, 63(Diciembre), 165–189.

Varadarajan, P. R., & Menon, A. (1988). Cause-related marketing: A coalignment of marketing strategy and corporate philanthropy. Journal of marketing, 52(3), 58–74.

Venable, B. T., Rose, G. M., Bush, V. D., & Gilbert, F. W. (2005). The role of brand personality in charitable giving: An assessment and validation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33(3), 295–312.

Vila López, N., Küster Boluda, I., & Aldás, M. J. (2000). Desarrollo y validación de escalas de medida en marketing. Servei de Publicacions. Universitat de València.

Weiss, A. M., Anderson, E., & Maclnnis, D. J. (1999). Reputation management as a motivation for sales structure decisions. Journal of Marketing, 63(4), 74–89.

Wheaton, B., Muthen, B., Alwin, D. F., & Summers, G. F. (1977). Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociological Methodology, 9(8), 84–136.

Wymer, W. W., & Samu, S. (2003). Dimensions of business and nonprofit collaborative relationships. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 11(1), 3–22.

Acknowledgments

This research has been funded by the project “La percepción de las alianzas entre los actores sociales”. Unit associated to CONICET – Social Sciences and Humanities Department. UCC 24503: Project 2016-2018 - 10120150100011CC.

A special acknowledgement to Natalia Muiño from Fundación Manos Abiertas, Córdoba, for her assistance, and to the suggestions made by Dr. María Mercedes Galán Galero from University of Extremadura.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appedix

Appedix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bianchi, E.C., Daponte, G.G. & Pirard, L. The impact of cause-related marketing campaigns on the reputation of corporations and NGOs. Int Rev Public Nonprofit Mark 18, 187–205 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-020-00268-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-020-00268-x