Abstract

In the current socio-political framework in South Africa children have been afforded the highest priority within government, affirming their legal status of right holders. Not only has the rights and needs of children been entrenched in the development strategies of the government, but children themselves have been guaranteed socio-economic rights and protection from abuse, exploitation, and neglect. Subsequently, knowledge and information on the well-being of children have become important pursuits. More specifically, current trends in international literature point to the critical importance of subjective perceptions of well-being in developing measuring and monitoring initiatives. The aim of the study was to determine the subjective well-being of children in the Western Cape region of South Africa. A cross-sectional survey design was employed with the use of stratified random sampling to select a sample of 1004 twelve year old children attending primary schools within the Western Cape Metropole. Descriptive statistics were used to present the findings across the different domains of well-being. The study forms part of the International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (Phase 1: Deep Pilot) and follows a cross-sectional survey design. The survey included a number of internationally validated scales. This paper reports on some of the findings of the Student Life Satisfaction Scale, the Personal Well-Being Index-School Children, and the single-item scale on Overall Life Satisfaction. The findings show that the composite scores for the three scales show a general trend towards high levels of subjective well-being; however, these scores are incongruent to objective indicators of well-being which point to a range of adverse childhood realities. Another key finding was the significant difference in the composite mean scores on the Student Life Satisfaction Scale of children from low and middle-income communities. Finally a significant difference was found between mean composite scores on the Student Life Satisfaction Scale (65.60) and the Personal Well-Being Index- School Children (81.90). The findings raise important considerations for the conceptualisation and measurement of child well-being in South Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

The children of South Africa have a long history of exposure to political violence, oppression, abuse, and affliction. Following the advent of democracy in 1994, the government made a series of legal commitments to redress the atrocities that children experienced in the past and to make South Africa a better place for all children. The late President Mandela made the first of these commitments, when he pledged that the needs and well-being of children would be prioritised. This was followed by a commitment to the implementation of the goals of the World Summit for children. On the 16th of June 1995, a significant landmark was reached for children’s rights in South Africa, when the president ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). This, along with the Section 28 of the Bill of Rights of South Africa’s Constitution, placed the needs of children as paramount within all development strategies of the government.

The National Programme of Action for Children (NPAC), co-ordinated by the Office on the Rights of the Child (ORC), was put in place to carry out the above commitments. According to the ORC, the National Programme of Action for Children “provides a holistic framework in which all government departments put children’s issues on their agendas. It provides a vehicle for co-ordinated action between NGOs, government and child related structures” (Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities, (DWCPD), 2012, p. 21). The ratification and legislative advancement of child specific instruments culminated in the development of the Children’s Act (No. 38 of 2005), the associated Children’s Amendment Act (No. 41 of 2007) as well as the recently promulgated Child Justice Act (2008). Acceding to these legal contracts has entrenched the rights and needs of children in the development strategies of the government as well as guaranteeing children’s socio-economic rights and protection from abuse, exploitation, and neglect. With children themselves now being elevated to the legal status of rights holders, with the government ultimately accountable as the principal duty bearer, children’s well-being is now afforded the highest priority within government. In 2009 the ORC was replaced by a dedicated Ministry, the DWCPD with the core function of improving the coordination of policies and monitoring mechanisms for children.

However, while the will and commitment of civic and government institutions have advanced social transformation and legislative frameworks, the benefits have not reached all children and their state and well-being remains adverse (Barbarin 2003). While aggregate data and objective indicators are available, researchers claim that the lack of child specific data is a major factor contributing to the innumerable burdens children face in their social, physical and psychological environments. Even though the South African government has initiated a number of programmes to alleviate the legacy of social inequality and deprivation of children, recent statistics posit a grave situation with regard to poverty, access to primary health care services, safety and education.

The latest South African Child Gauge (2013) edited by Berry et al. 2013, indicates that of the 18.5 million children within SA, 11 million live in impoverished conditions, with 60 % living below the lower-bound of the poverty line (equal to R575 per person per month in 2010). Specifically, within the Western Cape, 30.60 % of children (n = 542 000) were categorised as falling within the income poverty bracket. This lack of sufficient income impacts upon children’s rights to nutrition, education, and health care services. Other key indicators show the under-5 mortality rate at 56 per 1000 live births and an infant mortality rate of 40 per 1000 live births, in comparison to global under-5 mortality estimates of 48 per 1000 live births (United Nations Children’s Fund 2013). Additionally, violence and crime remain importunate threats to children in SA (United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2009). In SA between 2008 and 2009, approximately 50 000 children were victims of violent crimes (South African Police Services 2009). This figure increased to 56 500 children being victims of violent crime between 2009 and 2010 (UNICEF 2009). Further, child sexual abuse remains the most pertinent form of violence against children in the country (South African Police Service 2010). Statistics indicate that 61 % of children who have been the victim of child sexual abuse are younger than 15, while 29% were between the ages of 0 and 10 years (UNICEF 2009).

In 2012 the DWCPD initiated a large-scale project aimed at developing a comprehensive indicator framework to monitor the state and well-being of children and youth. While the focus was on improving monitoring systems and developing objective indicators of children’s quality of life, the importance of ascertaining subjective perceptions of well-being and collecting data from children themselves was highlighted. Indeed, current trends in international literature point to the critical importance of subjective perceptions of well-being in developing indicator systems of well-being. The current study hopes to contribute in this regard, by providing a snapshot of children’s subjective perceptions of well-being. It hopes to add to the database of child-specific data and contribute to the international dialogue on children’s subjective perceptions of well-being.

1.1 Aims of the Study

The primary aim of the study is to determine the subjective well-being of children in the Western Cape region of South Africa. More specifically the study aims to ascertain children’s perceptions of life satisfaction and personal well-being.

1.2 Well-Being

The nascent interest in children’s well-being has expanded exponentially since the adoption of the UNCRC. The propagation of the concept of well-being can be located in the work of Jahoda (1958) and more specifically in the concept of positive psychological health, and is later evident in studies of quality of life and happiness (See Casas 1997, 2000; Cummins 1995a), standard of living and health, as well as the field of social psychology. The conventional understanding of well-being was premised upon the absence of ill-health and disease (e.g., Moore 1997), with the prevention of problem behaviour (e.g., Moore and Keyes 2003) and promoting strengths and positive outcomes (e.g., Pollard and Rosenberg 2003). Contemporary notions of well-being have envisaged developing an integrated model that amalgamates the treatment and prevention of problem behaviour and the promoting strengths approaches (e.g., Pollard and Rosenberg 2003). However, a more positive conception of well-being and health was manifest in the World Health Organisations’ preface of its initial articles of association: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1948, as cited in Conti and Heckman 2012). Ryan and Deci (2001) indicate that the lack of consensus may, to some extent, be attributed to the inclination of two divergent interpretations of well-being; that is the hedonic and eudaimonic perspectives. Hedonic perspectives of well-being focus on subjective well-being or happiness and are frequently denoted in relation to circumventing pain and attaining pleasure; whereas eudaimonic perspectives focus on psychological well-being which is more broadly denoted as encompassing dynamic processes and the degree to which an individual is fully functioning in society and refers to concepts such as meaning of life, life goals, and self-actualisation (Casas 2011).

Considering the above, it is axiomatic that within the field, child well-being has been defined in various ways. Aked et al. (2009) define child well-being as a dynamic state “…emerging from the interaction between their external circumstances, inner resources and their capabilities and interactions with the world around them” (p.29). Pollard and Rosenberg define child well-being as, “A state of successful performance throughout the life course integrating physical, cognitive, and socio-emotional function that results in productive activities deemed significant by one’s cultural community, fulfilling social relationships, and the ability to transcend moderate psychosocial and environmental problems” (Pollard and Rosenberg 2003, p. 14). While these definitions point to the significance of the integrity between the internal and external world, they also suggest a reliance on society’s acknowledgement of childhood as a valid structural feature of society. In other words, making sense of child well-being is futile unless there is an acceptance of childhood in both everyday common sense discourse as well as human rights discourse. The near universal ratification of the UNCRC is testament to that at least in terms of the latter, substantial progress has been made in the past few decades.

While the UNCRC has been criticised for demonstrating more Western perspectives than others, it nonetheless affords a good starting point for conceptualising child well-being (Nieuwenhuys 1998). Presenting a normative framework for understanding children’s rights and well-being, the UNCRC is often regarded as the genesis of the child indicator movement, and along with the theoretical and methodological assertions of the ‘new sociology of childhood’ have been significant in driving the notion that children are valid social actors and constructors of knowledge, propagating for child centred research and the need for child specific data. Within the child indicator movement, what followed was the trend toward participatory techniques, a focus on children as the unit of analysis and investigating subjective well-being (Ben-Arieh 2008). Casas et al. (2013), with reference to the International Survey on Children’s Well-being (ISCWeb), motivate for the focus on children’s subjective perceptions which they believe is critical in assessing and contributing to overall well-being and quality of life.

With a history as far back as 1967, the concept of subjective well-being is epitomised in the Wilson’s (Avowed correlates of happiness), Bradburn’s (1969) (The structure of psychological well-being) as well as publication by Campbell, Converse and Rodgers (1976) and Andrews and Whitney (1976). Over the years there has been a progressive increase in studies focusing on subjective well-being. Within child indicator and child well-being research, however, the interest has been less concerted, with the discipline largely pre-occupied with developing objective indicators of well-being (Savahl et al 2014). Notwithstanding the languid start, the importance of researching subjective child well-being has proliferated in recent years. Indeed, within contemporary international dialogue, one would be hard pressed to find commentary that discounts the importance of subjective perceptions of well-being in measuring and monitoring initiatives and in assessing overall child well-being.

Subjective well-being is generally defined as “an umbrella term for different valuations that people make regarding their lives, the events happening to them their bodies and minds, and the circumstances in which they live” (Diener 2006, p. 400). Contemporary literature on subjective well-being suggests that the concept is often differentiated into a number of dimensions (Land et al. 2007; Pollard and Lee 2003; Zaff et al. 2003). Pollard and Lee (2003), after conducting a comprehensive systematic review, identified five key domains consistent in the literature: physical, psychological, cognitive and educational, social, and economic; Zaff et al. (2003) identified three: physical, socio-emotional and cognitive; whilst Land et al. (2007) identified seven: family economic well-being, health, safety/behavioural concerns, educational attainment, community connectedness, social relationships, emotional/spiritual well-being. These studies generally align to Cummins’ (1996) oft cited ‘attempt to order chaos’ wherein he conducted a systematic review to ascertain the common domains of subjective well-being. Cummins (1996) concluded that the domains revealed in the reviewed studies can be grouped into seven broad domains: economic and material well-being, health, safety, productive activity, place in community, intimacy, emotional well-being.

Whilst Fattore, Mason & Watson (2012) question the extent to which these domains are applicable to children and youth, others such as Land et al. (2012) point to the robustness and applicability across different population cohorts, including children and youth. Support for this contention can be located in participatory studies with children conducted by Savahl et al. (2014) and September and Savahl (2009) who found domains of subjective well-being that are closely aligned to those of Cummins (1996).

It is ostensible that well-being is not solely an individual property, but also a social property (Ben-Arieh 2009). This brings to the fore three salient motivations as to why the well-being of children necessitates particular attention (Fernandes et al. 2012). Firstly, the concern of child well-being is not limited to the present lives of children as it has corollaries for their future. Secondly, within South Africa, children remain affected by a range of adversities; and finally, despite burgeoning amount of research and theorisation on children’s well-being there is still a lack of child-specific information and data.

2 Method

The study forms part of the ISCWeb (Phase 1: Deep Pilot) and follows a cross-sectional survey design. While the International Project targeted three age groups (8, 10, 12), due to the exploratory nature of this phase of the study, the South African study only included the 12 year old cohort.

2.1 Research Context

Decades of systematic racial oppression resulted in the context of social and economic inequality and impoverishment amongst the majority of South Africa’s population. With a gini co-efficient of .70 (Bosch et al. 2010), South Africa is characterised by high levels of social inequality which has resulted in the stark disparities between the rich and poor. This has culminated in the segregation of communities and neighbourhoods into privileged or high socio-economic communities characterised by high income, high educational attainment, high levels of employment, and low incidence of violence; and disadvantaged communities characterised by low educational attainment and income, high rates of substance abuse, unemployment, and crime and violence. A key indicator of a disadvantaged and poverty-stricken community is household subsistence level, with the most recent available statistics indicating that 35.70 % of households in Cape Town live in poverty, with an income level of below R3500 per month (City Statistics—City of Cape Town, 2012). The current study was conducted in the Western Cape Metropole, which is a typical urban environment with a population of approximately 5.8 million. Participants were selected from both low and middle income communities.

2.2 Sampling

The sampling frame for the study included children attending primary schools within the four Education Management District Councils (EMDC’s) of the Western Cape Education Department (WCED) Metropole. A two stage stratified random sampling protocol was followed, ensuring that children from various cultural, income, and geographical groups were selected. In the first stage schools were stratified according to their location within the EMDC’s. Thereafter, schools were stratified by income level (middle or low income) and randomly selected from these strata. While it was envisaged to obtain an equal number of schools from low and middle income communities, the final sample consisted of eight schools from low income and seven from middle income communities. All the 12 year old children in the schools were selected to participate. A total of 1048 children participated in the study. After the data was cleaned, damaged and incomplete questionnaires were discarded. The final sample consisted of 1004 participants. Of these 58.6 % were from the low income and 41.4 % from the middle income group. Girls comprised 53.9 % whilst boys comprised 46.1 % of the sample.

2.3 Instrumentation

The original survey instruments developed by the core research group were in English and Spanish. For the purposes of the South African study the English version of the questionnaire was adapted to the South African context. This process included the cognitive testing, translation into Afrikaans and piloting of the 12 year old questionnaire. The cognitive testing process involved two focus groups with 10 children each. The participants of the focus groups were purposively selected from primary schools within the sampling frame. The responses of the participants of the focus groups assisted in the phrasing, refining and modification of items on the questionnaire. Thereafter, the revised questionnaire was translated in Afrikaans using the backward translation method. Following the translation, both questionnaires (English and Afrikaans) were piloted with a sample of 100 twelve year old children, randomly selected from low and middle income schools located in the sampling frame. This process focused on gathering pertinent information relating to how the test-takers responded to the stimulus material, the ordering or sequencing of the items, and the length of the questionnaires. Information gathered during the pilot was used to revise and finalise the questionnaires. A number of internationally validated scales were included in the questionnaire. These included the Student Life Satisfaction Scale (Huebner 1991), the Personal Well-Being Index-School Children (Cummins and Lau 2005), the single-item scale on Overall Life Satisfaction (Cummins and Lau 2005), and the Children’s Hope Scale (Snyder et al. 1997). This paper reports on some of the findings of the SLSS, PWI-SC, and the OLS.

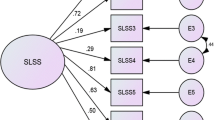

2.3.1 Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale

The seven-item Student Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS) was developed to assess children’s (age 8–18 years) global life satisfaction (Huebner 1991). The scale items are domain-free and require respondents to evaluate their satisfaction on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The initial version of the scale comprised ten items and was later reduced to seven items owing to further item analysis as well as data and reliability estimates (Huebner et al. 2003). The scale has been shown to display acceptable internal consistency, with alpha coefficients of 0.82 (Huebner 1991; Huebner et al. 2004), and 0.86 (Dew and Huebner 1994). The SLSS has also evinced convergent validity by correlating well with other life satisfaction measures (Dew and Huebner 1994; Huebner 1991) and overall life satisfaction (Casas et al. 2013). The scale has also been shown to display good criterion (Huebner et al 2003), discriminant (Huebner and Alderman 1993), and predictive validity (Suldo and Huebner 2004). To date, empirical guidelines for ‘cut-points’ that might classify children into optimal, adequate or low levels of life satisfaction have not been established. Furthermore normative scores from South African populations have not been established. To assist with comparison between scales, the SLSS has been transformed into a 100-point scale.

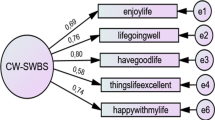

2.3.2 Personal Well-Being Index-School Children and Adolescents

Based on the original adult version, the Personal Well-Being Index-School Children (PWI-SC) was designed by Cummins and Lau (2005) to assess children’s subjective well-being. The scale evaluates a number of life satisfaction domains, namely standard of living, health, achieving in life, relationships, safety, community-connectedness and future security. The scale consists of seven items, representing the aforementioned domains, and is intended to display a “first level deconstruction of satisfaction with ‘life as a whole’” (Tomyn and Cummins 2011, p. 408). The original seven item scale is often adapted to include items on religion/spirituality and school experience. In the current study, the item on school experience has been included. Response options for the PWI-SC use an end-labelled 0–10 point scale, with 10, indicating complete satisfaction and 0, complete dissatisfaction. The PWI-SC generates a composite variable which is determined by calculating the mean for the items. The PWI-SC has shown an acceptable alpha coefficient of 0.82 (Tomyn and Cummins 2011). To assist with comparison between scales, the PWI-SC has been transformed into a 100 point scale.

2.3.3 Single Item on Overall Life Satisfaction

An item assessing Overall Life Satisfaction (OLS) (Cummins and Lau 2005) on an end-labelled 0–10 scale was also included, “How satisfied are you with your life as a whole?” The importance of including a single item on life satisfaction was identified by Campbell et al. (1976) and further corroborated by Cummins and Lau (2005) and Casas et al. (2013).

2.4 Procedure and Ethics

Once the schools were selected, the research team met with the principals and life skills teachers. An information session was arranged with the 12 year old children in the school where the aim, the nature of their involvement and ethics of the study were discussed. The participants were advised on the ethics principles of informed consent, confidentiality, the right to withdraw and privacy. Those who agreed to participate were requested to provide signed consent as well as obtain signed consent from their parents. Only those who returned the consent forms participated in the study. The questionnaires were administered following a researcher-administered protocol. This means that the items on the questionnaire were read to the participants by members of the research team while they were answering the questionnaire. This approach assisted participants who may have experienced difficulty in answering some items on the questionnaire and is generally used with young children and vulnerable groups. The average time of completion of the questionnaires was approximately 30 min.

2.5 Data Analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 21) to yield descriptive statistics such as means, cross-tabulations and frequencies to provide an overview of children’s subjective well-being.

2.6 Results

Table 1 above shows the mean composite scores for the three scales used in the study which is the SLSS, PWI-SC, and the OLS. The composite mean scores for the scales were as follows: for the SLSS it was 65.60 (sd = 18.59), for the OLS it was 85.10 (sd = 24.29), and PWI-SC, 81.90 (sd = 13.60).

3 Student Life Satisfaction Scale: Descriptive

Table 2 displays the item and composite mean scores of the SLSS for the low and middle income groups. The results show that the composite mean score for the low-income group was 64.13 (sd = 18.48) and 67.70 (sd = 18.58) for the middle-income group. Significant differences were observed between the income groups for item three (“I would like to change many things in my life” and item four (“I wish I had a different kind of life”, with the middle income group scoring higher than the low income group on both items.

4 Personal Well-Being Index-School Children: Descriptive statistics

Table 3 displays the item and mean composite scores of the PWI-SC, as well as the cross-tabulation between the items on the PWI-SC and income level. The results show a mean composite score of 81.33 (sd = 13.40) for the low income group and 82.73 (sd = 13.90) for the middle income group. Significant differences were found between the two income groups for item two (“Satisfied with relationships in general”), item seven (“Satisfied with things away from home”) and item eight (“Satisfied with future security”); with the middle income group scoring higher than the low income group on the three items.

5 Overall Life Satisfaction

Table 4 presents the mean scores for the single item on overall life satisfaction. An overall mean score of 85.10 (sd = 24.29) was obtained. No significant differences were observed across income or gender.

6 Discussion

The study aims to determine the subjective well-being of children in the Western Cape region of South Africa, specifically children’s perceptions of life satisfaction and personal well-being. While children in South Africa face countless risks and burdens in their daily lives which affects their overall well-being, it is poignant to note that the composite scores for the three scales show a general trend towards high levels of subjective well-being. However, these scores are incongruent to objective indicators of well-being which point to a range of adverse childhood realities. The absence of normative scores for South African child populations adds complexity to the interpretation.

Cummins (1995b), while ‘on the trail of the gold standard for subjective well-being”, noted the tendency for scores on subjective well-being measures to be negatively skewed. Indeed this ‘life optimism bias’ presents consistently within the literature. Early studies by Goldings (1969) for example, explained this phenomenon as being related to socially acceptable perceptions of happiness (as cited in Cummins 1995b). If happiness is positively regarded in a specific culture, then individuals are more inclined to respond in a positive way. Others such as Boucher and Osgood (1969) put forward the ‘Polyanna’ hypothesis to explain individuals’ preference to select items on the positive spectrum; while Heady and Wearing (1988, 1992) suggest that it may be linked to the need to maintain the integrity of the self (as cited in Cummins 1995b). Cummins (1995b) concludes that the negative skew in subjective quality of life data is ubiquitous; that a variety of psychological mechanisms could explain this phenomenon; and that the consistency of this phenomenon across a diverse range of studies is evident of a psychological set-point for subjective well-being. On the basis of this, Cummins (1995b) advocates for a single statistic, a ‘gold standard’ of subjective well-being’, that can be used across population cohorts. After reviewing a range of normative studies using a variety of subjective well-being measures, Cummins devised the ‘Percentage of Scale Maximum’ normative statistic, which he calculated at 75.02 ± 2.5 sd. Within the child indicator movement, the lack of normative data has limited the use of this statistic, with studies generally reporting composite mean scores that have been transformed into 100 point scales. Using this procedure, Casas et al (2013) report mean composite scores of between 70 and 80 for child populations of western countries on the Personal Well-Being Index.

While the scores of the current study are comparable to this and point to high levels of subjective well-being, it should be cautiously interpreted. This contention is especially pertinent if one considers Dawes et al’s. (1989, p. 631–632) assertion that “the past emphasis on children’s vulnerability will be replaced with an overemphasis on children’s resilience […] leading us to underestimate the very real instances of psychological distress that occur in contexts of violence.” Along with a somewhat misdirected pre-occupation with the concept of resilience as a panacea for adverse childhood experiences in South Africa, there is another real concern, that of desensitisation. Recent qualitative studies conducted with children and adolescents in various communities in the Western Cape show a marked desensitisation to adverse experiences such as community violence, abuse and neglect and socio-economic hardships (see e.g., Isaacs and Savahl 2013). Following Sen (1999) who makes reference to life satisfaction amongst people living in poverty, this desensitisation might lead to a normalisation and acceptance of unfavourable life conditions, where children and young people ‘learn to be satisfied’ with what they have.

A key finding of the study was the significant difference in the composite mean scores on the SLSS between children from low and middle-income communities. This finding is similar to that of Camfield (2012), Klocke et al. (2013) as well as findings from national surveys from OECD countries, indicating that life satisfaction varies in terms of income (that is, parental employment and family affluence). Additionally, for the two negatively phrased items in the SLSS, significant differences were found between the two income groups. Of particular interest was the large range between the minimum and maximum composite scores for the SLSS and PWI-SC. An analysis of these extreme scores however, showed no evidence of response set, which suggests that these responses were well considered and reasonably authentic. This may be representative of the different status of children’s lives in the sample and the diversity of the childhood experience, which may not only be due to income, but other social, political, historical and cultural factors.

The PWI-SC, however, which is domain specific, showed no overall significant differences between mean composite scores across income groups. There were, however, significant differences on three domains related to relationships in general, things away from home, and future security. Furthermore, another interesting finding is the difference between mean composite scores on the SLSS (65.60) and the PWI-SC (81.90). Considering that Savahl et al. (forthcoming) have shown acceptable fit statistics for these scales amongst various income groups, it is conceivable that this anomaly is caused by other factors. The different nature of the scales as being either ‘context or domain free’ (SLSS) or ‘domain specific’ (PWI-SC) is one of the possible explanations for this finding. It then follows that when the participants respond to questions regarding specific domains that they are optimistic about the nature of their well-being. Biswas-Diener and Diener (2001) found that individuals living in adverse circumstances report lower overall levels of life satisfaction and higher levels of life satisfaction with regard to specific life domains. Further support for this contention is found in qualitative work conducted by September and Savahl (2009), Savahl (2010) and Savahl et al. (forthcoming) who found that adolescents generally responded positively to discussions around specific aspects of their lives. However, deeper probing around general life experiences of children and adolescents reveal profoundly contrasting discourses, with rich narratives portraying adverse childhood experiences, trauma and credible threats to well-being. Further explanation can also be located in the ‘satisfaction paradox’ (Zapf, 1984, as cited in Olsen and Schober 1993), which refers to the state of being satisfied regardless of objectively unsatisfactory living conditions (Neff 2007).

No significant differences were observed across gender for any of the items on the scales. This is in itself an interesting finding as gender is a contentious variable in well-being literature. The findings are further surprising given the major social problem of gender-based violence in South Africa in general, and the Western Cape in particular.

7 Conclusion and Recommendations

While the socio-political landscape in South Africa is geared toward improving the lives and well-being of children, findings which suggest high levels of subjective well-being are counterintuitive to this agenda and may create a false sense of achievement and negatively affect the impetus of policy initiatives and service delivery. Furthermore, as these findings do not align to the more objective indicators of well-being, there is a risk that the focus on subjective well-being would be downplayed. With subjective well-being being in its infancy in South Africa and the subsequent lack of empirical initiatives, plotting a course forward is an extremely difficult task. Cross-cultural adaptation and translation of internationally validated instruments need to be advanced. Further development of subjective well-being indexes, such as Casas et al.’s (2013) ‘General Index of Children’s Subjective Well-Being’ and Rees et al.’s (2010) ‘Short Index of Child Well-Being’ and its validation in local contexts is recommended. This along with large scale studies using weighted representative samples to develop normative scores would be useful especially considering the diversity of the childhood experience in the South African context. Finally, given the tendency for subjective well-being measures to present with negatively skewed scores, it is recommended that studies aimed at determining subjective well-being include both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Depth exploration, afforded by qualitative techniques would allow for deeper access to the meanings associated with subjective well-being and would make for a more comprehensive understanding of subjective well-being and quality of life.

References

Aked, J., Steuer, N., Lawlor, E., & Spratt, S. (2009). Backing the future: why investing in children is good for us all. London: New Economics Foundation.

Barbarin, O. (2003). Social risks and child development in South Africa: a nation’s programme to protect the human rights of children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 73(3), 248–254.

Ben-Arieh, A. (2008). The child indicators movement: past, present, and future. Child Indicators Research, 1, 3–16.

Ben-Arieh, A. (2009). From child welfare to children well-being: the child indicators perspective. In S. B. Kamerman, S. Phipps, & A. Ben-Arieh (Eds.), From child welfare to children well-being: an international perspective on knowledge in the service of making policy. Dordrecht: Springer.

Berry, L., Biersteker, L., Dawes, A., Lake, L., & Smith, C. (2013). South African child gauge (2013). Cape Town: Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town.

Biswas-Diener, R., & Diener, E. (2001). Making the best of a bad situation: satisfaction in the slums of Calcutta. Social Indicators Research, 3(55), 329–352.

Bosch, A., Roussouw, J., Claassens, T., & du Plessis, B. (2010). A second look at measuring inequality in South Africa: a modified gini coefficient. School of Development Studies, Working paper (58). University of Kwazulu-Natal.

Camfield, L. (2012). Resilience and well-being among urban Ethiopian children: what role do social resources and competencies play? Social Indicators Research, 107, 393–410.

Casas, F. (1997). Children’s rights and children’s quality of life: conceptual and practical issues. Social Indicators Research, 42(3), 283–298.

Casas, F. (2000). Quality of life and the life experience of children. In E. Verhellen (Ed.), Understanding children’s rights. Ghent: University of Ghent.

Casas, F. (2011). Subjective social indicators and child and adolescent well-being. Child Indicators Research, 4(4), 555–575.

Casas, F., Bello, A., Gonzalez, M., & Aligué, M. (2013). Children’s subjective well-being measured using a composite index: what impacts Spanish first-year secondary education students’ subjective well-being? Child Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s12187-013-9182-x.

City Statistics—City of Cape Town (2012). Accessed from https://www.capetown.gov.za/en/stats/Documents/City_Statistics_2012.pdf

Conti, G., & Heckman, J. J. (2012). The economics of child well-being. IZA Discussion Paper No. 6930. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2164659.

Cummins, R. A. (1995a). The comprehensive quality of life scale: theory and development: health outcomes and quality of life measurement. Canberra: Institute of Health and Welfare.

Cummins, R. A. (1995b). On the trail of the gold standard for subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 35, 179–200.

Cummins, R. A. (1996). The domains of life satisfaction: an attempt to order chaos. Social Indicators Research, 38, 303–328.

Cummins, R. A., & Lau, A. D. L. (2005). Personal wellbeing index: school children (PWI-SC) (3rd ed.). Melbourne: Deakin University.

Department of Women, Children and People with Disabilities (DWCPD) (2012). United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC): combined second, third and fourth periodic state party report to the Committee on the Rights of the Child (Reporting period: 1998–June 2012.

Dew, T., & Huebner, E. S. (1994). Adolescents’ perceived quality of life: an exploratory investigation. Journal of School Psychology, 33, 185–199.

Diener, E. (2006). Guidelines for national indicators of subjective well-being and ill-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 397–404.

Fernandes, L., Mendes, A., & Teixeira, A. C. (2012). A review essay on the measurement of child well-being. Social Indicators Research, 106(2), 239–257.

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the student’s life satisfaction scale. School Psychology International, 12, 231–240.

Huebner, E. S., & Alderman, G. L. (1993). Convergent and discriminant validation of a children’s life satisfaction scale: its relationship to self- and teacher-reported psychological problems and school functioning. Social Indicators Research, 30, 71–82.

Huebner, E. S., Suldo, S. M., & Valois, R. F. (2003). Psychometric properties of two brief measures of children’s life satisfaction: The students’ life satisfaction scale (SLSS) and the Brief Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS). Paper prepared for the Indicators of Positive Development Conference, March 12–13, Washington, DC.

Huebner, E. S., Valois, R. F., Suldo, S. M., Smith, L. C., McKnight, C. G., Seligson, J. L., & Zullig, K. J. (2004). Perceived quality of life: a neglected component of adolescent health assessment and intervention. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34(4), 270–278.

Isaacs, S. A., & Savahl, S. (2013). A qualitative inquiry investigating adolescents’ sense of hope within a context of violence in a disadvantaged community in Cape Town. Journal of Youth Studies. doi:10.1080/13676261.2013.815703.

Jahoda, M. (1958). Current concepts of positive mental health. New York: Basic Books.

Klocke, A., Clair, A., & Bradshaw, J. (2013). International variation in child subjective well-being. Child Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s12187-013-9213-7.

Land, K. C., Lamb, V. L., Meadows, S. O., & Taylor, A. (2007). Measuring trends in well-being: an evidence based approach. Social Indicators Research, 80, 105–132.

Land, K. C., Lamb, V. L., & Meadows, S. O. (2012). Conceptual and methodological foundations of the child and youth well-being index. In K. C. Land (Ed.), The well-being of America’s children: developing and improving the child and youth well-being index (pp. 13–28). New York: Springer.

Moore, K. A. (1997). Criteria for indicators of child well-being. In R. M. Hauser, B. V. Brown, & W. R. Prosser (Eds.), Indicators of children’s well-being (pp. 36–44). New York: Russell Sage.

Moore, K., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2003). A brief history of well-being in children and adults. In M. H. Bornstein, L. Davidson, C. L. M. Keyes, & K. Moore (Eds.), Well-being: positive development across the life course (pp. 23–32). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Neff, D. F. (2007). Subjective well-being, poverty, and ethnicity in South Africa: insights from an exploratory analysis. Social Indicators Research, 80, 313–341.

Nieuwenhuys, O. (1998). Global childhood and the politics of contempt. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 23(3), 267–289.

Olsen, G. I., & Schober, B. I. (1993). The satisfied poor: development of an intervention-oriented theoretical framework to explain satisfaction with a life in poverty. Social Indicators Research, 28(2), 173–193.

Pollard, E. L., & Lee, P. D. (2003). Child well-being: a systematic review of the literature. Social Indicators Research, 61(1), 59–78.

Pollard, E. L., & Rosenberg, M. L. (2003). The strength based approach to child well-being: Let’s begin with the end in mind. In M. H. Bornstein, L. Davidson, C. L. M. Keyes, & K. A. Moore (Eds.), Well-being: positive development across the life course (pp. 13–21). New Jersey: Laurence Earlbaum.

Rees, G., Goswami, H., & Bradshaw, J. (2010). Developing an index of children’s subjective well-being in England. London: The Children’s Society.

Republic of South Africa (2005). Children’s Act, No. 38 of 2005. Pretoria: Government Printers.

Republic of South Africa (2007).Children’s Amendment Act (No. 41 of 2007). Pretoria: Government Printers.

Republic of South Africa (2008). Child Justice Act. Pretoria: Government Printers.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Savahl, S. (2010). Ideological constructions of childhood. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of the Western Cape: Bellville.

Savahl, S., Malcolm, C., Slembrouk, S., Adams, S., Willenberg, I., & September, R. (2014). Discourses on well-being. Child Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s12187-014-9272-4.

Savahl, S. Casas, F. & Adams, S., Noordien, Z. & Isaacs, S. (forthcoming). Testing two measures of subjective well-being amongst a sample of children in the Western Cape region of South Africa. University of the Western Cape.

September, R., & Savahl, S. (2009). Children’s perspectives on child well-being. Social Work Practitioner/Researcher, 21(1), 23–40.

South African Police Service (2010). Crime Situation in South Africa: annual report.

Suldo, S. M. & Huebner, E. S. (2004). Does life satisfaction moderate the effects of stressful life events on psychopathological behavior in adolescence? School Psychology Quarterly.

Tomyn, A. J., & Cummins, R. A. (2011). The subjective wellbeing of high-school students: validating the personal well-being index- school children. Social Indicators Research, 101, 405–418.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2009). Child friendly cities. Retrieved 10 January 2011 from: http://www.childfriendlycities.org/en/to-learn-more/examples-of-cfc-initiatives/south-africa.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2013). Levels and trends in child mortality: Report 2013. UNICEF.

Zaff, J. F., Smith, D. C., Rogers, M. F., Leavitt, C. H., Halle, T. G., & Bornstein, M. H. (2003). Holistic well-being and the developing child. In M. H. Bornstein, L. Davidson, C. L. M. Keyes, & K. A. Moore (Eds.), Well-being: positive development across the life course. New Jersey: Laurence Earlbaum.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Savahl, S., Adams, S., Isaacs, S. et al. Subjective Well-Being Amongst a Sample of South African Children: A Descriptive Study. Child Ind Res 8, 211–226 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9289-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9289-8