Abstract

This study uses newly developed international measures in order to determine the prevalence of two types of bullying: Active (being hit by other children in school) and Passive (being left out by classmates), among 8, 10 and 12 year old Algerian school children. It also attempts to draw the profile of the victims and to assess the effects of bullying on children’s Subjective Well-being (SWB). Data have been obtained from a total of 1,452 school children.

The results indicate that 15.1, 9.9 and 12.3 % of respectively 8, 10 and 12 year students have been victims of active bullying, and respectively 16.3, 15.8 and 20.6 % have been victims of passive bullying during the month that precedes data collection. It has been noticed that boys use more direct methods, with an increasing frequency with age, but both gender groups equally use indirect methods of bullying. Furthermore, the findings suggest that bullying victimisation is more present among children belonging to less advantaged families, families changing house and changing local area. Absenteeism, though found high in Algerian schools, is much frequent amongst victims of bullying. And, significant differences are found in most of the SWB ratings in favour of children who have not experienced bullying victimisation.

Finally, regression analyses show that passive bullying and age have strong negative effects on satisfaction with life as a whole, but this effect has been reduced when lack of rewarding material facilities, gratifying living environments, good health and self-confidence were introduced in the second step.

The results have been discussed on the light of previous international research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Research on bullying in schools has flourished since the work of Dan Olweus and eventually other scholars worldwide. The subject has become a major multidisciplinary phenomenon, involving: Psychologists, sociologists, educationalists, pediatricians, statisticians and geographers (Elamé 2013) and new forms and variations of bullying behaviours are continuously unveiled. As a consequence, the notion of bullying has expanded to include not only physical harassment and harsh treatment that physically strong students exert on the weaker ones, but also all other possible forms of harassment, including mean gestures and facial expression, gossiping, and spreading rumours (Koo 2007). Intimidating treatments received through the Internet are also classified as ‘Cyber or Electronic Bullying’ (Moore et al. 2012).

The importance of researching bullying and developing prevention programs lies not only in its detrimental consequences on the bullied child, but also its repercussions on the wider societal order (Jacobson 2007). No doubt, rearing children in a violent and an unfriendly atmosphere undermines the whole societal harmony and peace.

Furthermore, the results of previous research with regard to the effects of bullying on the victim child are alarming. They comprise important biological consequences such as changed hormone reactivity and altered brain structures (Olweus, D and Breivik 2014). Concurrent evidence shows that the mental health of these victims can also be at risk (e.g., Arseneault et al. 2010). Georgiou (2008) suggests that male gender and depressive symptoms are associated with many types of bullying behavior and experience.

The school life of bullying victims also suffers greatly. Self-reported bullying and victimisation are linked to changes in pupils’ sense of school belonging and perceptions of their classroom climate (Pryce and Frederickson 2013), and also with falling achievement for all racial/ethnic groups (Williams and Peguero 2013). Nevertheless, many factors may mediate these relationships, such as living with a single parent, parental style, mainly maternal responsiveness and over-protection of the child (Georgiou 2008). Gender is an important predictor of the dominating form of bullying. For instance, girls are ‘more likely than boys to experience indirect forms of bullying such as teasing’ (Carbone-Lopez et al. 2010: 332).

From an ecological perspective, it has been made clear that bullying increases among children, who frequently watch television, lack teacher support, have themselves been bullied, attend schools with unfavorable environments, do not receive emotional support from their peers, and have teachers and parents who put low expectations on their school performance (Barboza et al. 2009). In other words, deficits in the social climate enhance bullying practices, but social support systems mediate bullying behavior irrespective of the student’s racial/ethnic characteristics, parental income levels or media influences (Boulton et al. 2013). Furthermore, it has been proposed that the number of friends and the ability to talk to these friends increases the likelihood of bullying. Bullying may not simply be an individual response to a particular environment but is a peer-group behavior (Salmivalli 2010; Bradshow et al. 2009).

School-level indicators of disorder (e.g., student–teacher ratio, concentration of student poverty, suspension rate, and student mobility) have been identified as potential predictors of bullying-related attitudes and experiences. But, student-level characteristics (i.e., sex, ethnicity and status in school) are also relevant to students’ retaliatory attitudes, perceptions of safety, and involvement in bullying (Bradshow et al. 2009).

It could be concluded therefore that school bullying is a complex phenomenon which deserves researchers’ and policy makers’ attention at all levels. Its destructive consequences and its prevention should be recognised as a priority in all societies. At least, decision makers should know that from a cost –benefit point of view, victims of bullying are “overconsumers” of society’s health and social support systems. According to Olweus, D and Breivik (2014) society can spare as much as two million dollars by preventing the life-course development of just one single marginalized/victimized case. Undoubtedly, societies with underperforming health systems will suffer greater pressures as a consequence of high prevalence of bullying. Finally, it should be noticed that in his well-known definition Olweus (1993) stipulated that bullying covers any physical, verbal or psychological attack or intimidation that is intended to cause fear, distress or harm to the victim. Our operational definition is restricted to two forms of bullying victimisation only: Direct physical harm (being hit by schoolmates) and indirect harm (being left out by classmates).

1.1 Subjective Well-Being

The present research aims to throw some light on the incidence of bullying victimisation and the probable relationship with subjective well-being in the country of Algeria. The concept of ‘Subjective well-being’ covers people’s evaluations of their life and their life domains. Its identified complementary components are a high frequency of positive and a low frequency of negative affects (e.g., Diener et al. 1999). Increasing subjective well-being is not only sought for its intrinsic value, but also because people with such a quality are expected to be happier, more efficient in their tasks and succeed better in diverse life situations (Diener et al. 1999). Many economists and policy makers are campaigning towards the recognition of subjective well-being as a policy outcome measure (Helliwell and Barrington-Leigh 2010).

In comparison to adults, research on children’s well-being is lagging behind (Casas et al. 2014). Despite this, such a research is yielding very important results. In Algerian children, Tiliouine (2014a) used the Personal Wellbeing Index (PWI) with young students and confirmed that they rated higher in satisfaction questions compared to the adults’ general populations. Casas et al. (2014) tested three different versions of the PWI in Algeria and Spain and found them equally suitable for measuring SWB, despite the cultural differences between the two societies. But, the fall of SWB scores with increasing age was more abrupt in Algeria than in Spain maybe because of the different economic development levels between the two countries.

The present research has been designed to collect evidence and expand the available research data on the relationship between bullying victimisation and subjective well-being. Goswami (2012) asserted that the recent inclusion of children’s experience on bullying has also helped research on social relationships and subjective well-being to cross new boundaries (p. 576). Generally, previous international research has shown that the experiences of being bullied decrease young people’s well-being (Olweus, D and Breivik 2014; Goswami 2012). Even electronic bullying has a pervasive relationship with adolescents’ life satisfaction reports across a variety of important life domains, but as Moore et al. (2012) argue global life satisfaction remains unaffected. Research, however, remains inconclusive with regard to the effect of school on well-being because of a lack of a good theory or theories to help conceptualise and test such complex relationships (Bacete et al. 2014).

1.2 The School System in Algeria

This research is important for many reasons, because, firstly, very little is known about the school system of Algeria. Furthermore, this country may exemplify what is happening in other Developing Countries where educational institutions are increasingly coming under pressure, not only because of the growing number of school attendees (up to 7.5 million students representing one fifth of the whole Algerian population, University students not included), but also because of the increasing aspirations of society and the insistent call for an improved quality education.

The latest reform of the educational system in Algeria (Education Act 2008, www.jora.dz) set clearly quality education as a guiding aim, in the knowledge that since the independence of the country in 1962 (from the French colonisation) and until the 1980s the socialist, single party system struggle was how to guarantee equal schooling opportunities to all school age children (Tiliouine 2014b). Up to 2009, 97 % were granted schooling (Bousenna et al. 2009). Despite this, school evaluation indicators have not been adjusted to take into account the new needs of an evolving social context (Lakhdar et al. 2012).

Increasing parents’ role in decisions related to the education of their children and participation of the children themselves in this process have been recognised among the strategic priorities of the ‘Plan National d’Action pour les enfants 2008-2015’ published by the Algerian Ministère Délégué Chargé de la Famille et de la Condition Féminine (2008: 38–39). But, no tangible actions are proposed on the way to achieve these aims. Certainly, encouraging research on adolescents’ and children’s well-being is a valuable tool on that direction.

Violence in Algerian schools remains widespread. The figures released by the Ministry of Education indicate that between 2001 and 2007 more than 59,000 victims of violence have been registered, including teacher and student victims and hence, school violence has been qualified as a ‘social earthquake’(Liberté, Daily Newspaper, 18th of March, 2014). However, the country’s turmoil of the 1990‘s, which resulted in a death toll of more than 200,000 people, has left no one indifferent with regard to all forms of violence in society. Many NGOs and government agencies are benefitting from International experience to combat school violence. For instance, Newspapers have reported that the Foundation Boucebci in partnership with the European Union is running a program entitled “Reduction of violence in schools”.

1.3 Objectives of the Research

This research attempts to contribute to the ongoing debate regarding school violence through the effort of providing field data on active and passive bullying victimisation and weighing their effects on children’s well-being in this particular social context. Active bullying victimisation is exemplified in being hit by other school mates, while passive bullying victimisation (relational bullying) means that the child has experienced being left out by his class-mates during the month preceding the research.

The research specifically seeks to address the following objectives: 1. to study the prevalence of peer bullying in different age clusters: 8, 10 and 12 year old students; 2. to identify some of the personal and socio-cultural characteristics of bullying victims; 3. to compare self-declared victims and non-victims on a variety of International SWB measures; and finally to test the predictive value of demographic variables (gender and age), the experience of bullying and selected life domains items in explaining satisfaction with life as a whole.

2 Methods

2.1 Sample

Three age groups participated in the study: 8 and 10 year olds were recruited from 8 primary schools, and 12 year olds from 3 Middle schools. With the exception of the youngest group, girls slightly outnumber the boys (Table 1).

2.2 The Questionnaire

The questionnaire has been developed within the International Survey of Children’s Well-Being (ISCWeB) project. This project main aims are: to produce a cross cultural tool and collect solid data on children’s lives, perceptions, aspirations and the diverse facets of their well-being. Such data are necessary to improve children’s well-being ‘through influencing opinion leaders, decision makers, professionals and the general public’ in the local and international arenas. Three versions of the questionnaire have been developed each for a specific age group. Information on the project and the latest versions of the questionnaires can be accessed through the following link: http://www.isciweb.org/?CategoryID = 190. All the questionnaire versions comprise eight life domains and aspects of children’s life: The home and the people they live with, money and things they have, relationships with friends and other people, the area where they live, their school, their health, time management and leisure time and self concept. Specifically, two questions are included in all the questionnaire versions to explore the experience of bullying victimization:

-

1.

In the last month, how often were you hit by other children in your school (Don’t know, Never, Once, 2 or 3 times and more than 3 times)?

-

2.

In the last month, how often were you left out by other children in your class (Don’t know, Never, Once, 2 or 3 times and more than 3 times)?

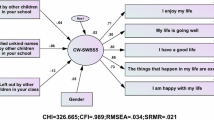

In addition, the 10 and 12 year old students’ questionnaires comprise among others, 3 well-known psychometric scales: The Student Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS, Huebner, 1991) and the one item Overall Life Satisfaction (OLS), the Personal Well-being Index - School Children (PWI-SC, Cummins and Lau 2005) and The Brief Multidimensional Student Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS, Seligson et al. 2003).

The Student Life Satisfaction Scale

(SLSS, Huebner, 1991) comprises 4 items, e.g. My life is going well. In this study, the SLSS has solid psychometric properties, with reliability coefficients of .76 in 10 year olds and .85 in 12 year olds. The correlation between the items range between .30 and .36 in the former and .47 and .70 in the latter group. In both cases, principal factor analysis has yielded a single factor explaining 60.82 % of the variance in the 10 year olds and 69.82 % in the 12 year olds, with loadings higher than .63 and .76 in each age group respectively.

The Personal Well-being Index

(PWI-SC) comprises 5 items only, e.g. Satisfaction with all the things you have. It has been judged suitable as a cross-cultural measure (Casas et al. 2014, Casas and Rees 2015). Though, reliability coefficients here have been moderate, reaching .59 and .61 respectively in the 2 age groups. The correlations between the items range from: .09 to .38 in the first and .18 to .31 in the second group. Also, principal factor analysis has yielded a single factor explaining respectively 38.37 % and 39.23 % of the variance and loadings above .53 in both cases.

The Brief Multidimensional Student Life Satisfaction Scale

(BMSLSS, Seligson et al. 2003) comprises 5 items, e.g. satisfaction with people you live with. Reliability coefficients have been respectively .53 to .66 respectively in each age group. The correlations between the items range from .10 to .32 in the 10 year old group and .19 to .39 in the remaining group. In both cases, principal factor analyses has yielded a single factor with loadings of respectively .44 and .52 and explaining 43.45 % of the variance in the same group order. All three measures have satisfactory measurement qualities (Casas and Rees 2015).

2.3 Procedure

The Algerian data, used in this paper, has been collected within the first wave (the large pilots) of the ISCWeB survey by a team from the research unit of the Laboratory of Educational Processes & Social Context (Labo-PECS) of the University of Oran in Senia Circumscription, Province of Oran (South of Algeria).

The Arabic version of the questionnaires was translated through forward and back translation of the original English language, and underwent extensive pilot testing and focus group discussion. The printed questionnaires were administered to children during their normal teaching sessions after acquiring official authorisation of the Directorate of the Oran County, the school headmasters’, classroom teachers’ and the children’s consent. Trained researchers worked with students in couples in each classroom.

Schools were randomly selected from the existing list of schools of the Province of Senia, Oran, with the help of the officials of the Directorate of Education in Oran County. A maximum of two class groups per age and per school completed the questionnaires. In case, the school had more than the needed two class groups, we took the two classrooms, which were the nearest to main school entrance.

2.4 Data Analyses

The data of each age cluster are analyzed separately in order to estimate the prevalence of bullying in each cluster, then two groups in each cluster are created and described on the basis of the frequency of the bullying victimization: Those who have not experienced bullying (non-victims) and those who have been either hit (herafter, Active bullying) or left out by their mates (hereafter, Passive Bullying) on 2 to 3 occasions or more (victims) during the same period of the preceding month to data collection. Cross-sectional comparisons are calculated to draw a realistic and detailed picture of the characteristics of the victims and non-victims of bullying.

Finally, regression analyses are conducted to estimate the contribution of selected domains of life in rating Overall Life Satisfaction (OLS) in the target groups. Past research (Tiliouine 2014a, Casas et al. 2014, Casas and Rees (2015) has proved that these domains have been powerful contributors to satisfaction with life as a whole in Algeria and many other countries. We wanted to explore whether our data would produce the same pattern of relationships.

3 Results

3.1 The Prevalence of School Bullying

Table 2 indicates that 15.1 %, 9.9 % and 12.3 % of respectively 8, 10 and 12 year old students report being victims of active bullying during the preceding month. Whereas, 16.3, 15.8 and 20.6 % of respectively 8, 10 and 12 year old students report being victims of passive bullying during the same period. It is suggested therefore that this latter form of bullying is more common in Algerian schools (Tables 3 and 7).

3.2 Characteristics of Bullying Victims

Gender

It has been noticed that 59.8, 60.9 and 76.5 % of active bullying victims in the 8, 10 and 12 age groups are male students. Males in passive bullying are 57.1, 48.4 and 53.6 % in same age group order.

Generally, active bullying victimisation increases with age among boys. They are more than 76 % of all victims in 12 year olds. Passive Bullying is to some extent found in both gender groups with a marked increase in the younger age group.

Family Financial Background

4.9 % of 8 year olds, 10.9 % of 10 year olds, and 21.6 % of 12 year olds say they have good clothes for school whereas 48.8 % of 8 year olds, and 43.1 % of 10 year olds, and 56.9 % of 12 year olds do not have access to a computer at home. Finally, 50.6 % of 8 year olds, 53.8 % of 10 year olds and 59.6 % of 12 year olds declare not access to the Internet. These figures are slightly higher than their non-victim counterparts, suggesting that a good proportion of the victims come from financially less advantaged families.

In all the examined comparisons, victims outnumber those who are not, in lacking good clothes and in having no access to a computer. With the exception of the 10.5 difference in the 8 year olds group regarding access to Internet, all remaining differences are marginal.

Generally, these figures suggest that victims of both bullying kinds belong to financially less advantaged families. Despite this, the figures indicate that the coverage of Internet connection in the whole country remains weak.

However, this apparent trend has not been strongly confirmed through the direct question on how often the child worries about how much money their family has. The correlations between active bullying and the level of worry on the one hand and this latter and passive bullying on the other hand, are not significant (0.06 and -.034 respectively).

Stability in the child’s Life

The results on stability in life are highly relevant to the bullying phenomenon. The two eldest groups have been asked whether they moved house, changed school, changed local area, lived in another country for more than 3 months and if living with the same parents or carers as in the preceding year. In the 10 year old group, victims of active bullying have higher percentages (12.2 % moved house, 2.4 % changed school, 17.1 % changed local area, 7.5 % lived in another country and 10 % have not been living with the same parents or carers). In comparison, non-victims have reported the following figures: respectively: 14.8, 12.8, 16.1, 6.5 and 11.1 %. The highest difference concerns changing schools among non-victims. Other comparisons are inconclusive.

In the 12 year group, 28 % moved house, 27.7 % changed school, 24.4 % changed local area, 11.8 % lived in another country and 24 % have not been living with the same parents or carers. In comparison, the non-victims registered the following figures, respectively: 15.9, 23.2, 9.5, 7 % and 19.2 %. The largest difference in percentage points are found in: moving house (12.1 points), and changing local area (14.9 points).

As for passive bullying, in the younger group: 18.8 % moved house, 6.5 % changed school, 22.2 % changed local area, 9.5 % lived in another country and 12.7 % have not been living with the same parents or carers. Whereas, the non-victims registered the following results, respectively: 14.2, 15.2, 14, 9.1, and 10.2 %. The largest differences in percentage points concern: changing local area in favour of victims of active bullying (8.2 points) and changing school in the opposite direction (8.7 points).

In the 12 year olds, figures for victims of active bullying are: 25.3 % moved house, 18.5 % changed school, 15 % changed local area, 10.78 % lived in another country and 21.3 % have not been living with the same parents or carers. In comparison, the non-victims registered the following figures: 14.7, 23.1, 9.8, 8.4 and 19.1 %. The difference is apparent in moving house (10.6 points), and changing local area (5.2 points) in favour of bullying victims.

Absenteeism

Respondents have been asked on how many days they have missed school because they felt unwell in the preceding month. When 3 and more days missed are taken as an indicator of absenteeism, the results are as follows: In the active bullying groups, 25.6 % of 8 year old victim students report being absent compared to 9.1 % non-victims. In the 10 years group, 23.5 % report absenteeism in victims compared to 9.4 % of non-victims. In the remaining groups, 2.2 % of victims compared to 13.8 % of non-victims are targets of absenteeism.

The passive bullying groups report the following figures: 22.6 % of victims compared to 8.2 % in non- victims are targets (14.4 points difference). In the 10 year old group, the figures have been, respectively: 23.3 % versus 102 % (13.1 points difference). In the eldest group, passive bullying, 11.8 % of the victims versus 15.4 % of non- victims have been targets of absenteeism. Here, absenteeism is more frequent in victims with a marginal 3.5 percentage point difference.

3.3 Comparisons in Subjective Well-Being

Firstly, it should be noted that significant differences are registered between the victims and non-victims of active bullying across the three psychometric measures (Table 4), suggesting that the victims’ satisfaction with life is challenged. This is supported to a great extent by the added individual items: Overall happiness, satisfaction with the people they live with, family life, safety at school, freedom the child has, friends, and satisfaction with other children in class. Nevertheless, some items did not vary for 10 year olds: OLS, the house, other people in the family, school and the way that the child looks (Table 4).

The trend of significant differences noticed in active bullying across the three psychometric measures has been confirmed in passive bullying (Table 5). The added individual items: Overall happiness (not significant in the 10 year old groups), safety at school, freedom the child has, and satisfaction with other children in class, are in the same direction. Mostly family factors showed no significant differences. Nevertheless, some items did not vary for 10 year olds: Happiness, the house, school, and the way that the child looks (Table 5).

3.4 Correlations Between the two Forms of Bullying are as Follows

In 8 years group (r = .40, N = 538), in 10 years group (r = .26, N = 387) and in 12 years group: r = 29, N = 404). All correlations are significant (p < .001).

3.5 Contributing Factors in Satisfaction With Life

Two-step regression analyses have been conducted to estimate the contributing factors in satisfaction with life ratings. In the first step, age and passive bullying have been found to negatively affect satisfaction with life at significant levels (p < .001 and p < .005 respectively) but gender and active bullying have a marginal effect. When these four factors were included along with the five selected life domains (‘the things you have’, ‘health’, ‘yourself’, and ‘the area where you live’ in the second step, all the first four factors have lost their effect. Meanwhile, all added life domains are found to predict strongly life satisfaction, with the exception of ‘the school you go to’ (change in R2 = .25) (Table 6). The results are highly enlightening.

4 Discussion

This research is important in many ways. It has firstly been conduced in the largest African country of Algeria which shares a lot of characteristics with the less developed world. Secondly, it has used three different age groups of young girls and boys. Thirdly, it has used a new cross-cultural questionnaire, which underwent close psychometric examination (Casas and Rees (2015). Furthermore, it has covered two well-known bullying types; direct or active and indirect or passive bullying. These two forms have also been linked to Subjective well-being. Therefore, such work brings a lot of new information and can be a departure point for improved school conditions for millions of children in the future. Its implications are further discussed in the following section, referring to past international research evidence and the peculiarities of the local educational system.

The results reveal that active victimisation increases with age among boys, but the passive form is equally present across gender groups. Similar results have been reported elsewhere. Boys usually use violent behaviours more than girls, and generally the majority of girls are bullied by girls and the majority of the boys are bullied by boys (e.g. (Arslan et al. 2011).

Our results also suggest that bullying victimization is more present among children belonging to less advantaged families. Despite that the used indicators are not solid enough to weigh the general financial situation of families, having good clothes for school, having access to computer at home and having access Internet can be relevant in a developing country such as Algeria. The perceived inequality in the capacity to acquire such life facilities may explain the resentfulness of some children to engage in rewarding relationships with their classmates. If this is the case, income inequality in families has its costs for children. In general, concentration of poverty is a driving factor for more bullying (Bradshow et al. 2009).

It is also interesting to note that two indicators of the degree of stability in the child’s life (changing house and changing local area in the preceding year) have been found more significant in bullying victims. It follows therefore that children of families who move to live in another place should receive support from the school system in a way that facilitates their gradual integration in the new social environment. It has previously been shown that bullying increases in unfavorable environments, where emotional support from peers is lacking (Barboza et al. 2009; Boulton et al. 2013). Besides, bullying can be in its large part a peer-group behavior (Salmivalli 2010; Bradshow et al. 2009).

Absenteeism is more frequent among all ages and across both forms of bullying victims (twice its level in non-victims). This phenomenon is noteworthy and should be carefully monitored. When the proportion of students missing 3 and more school days in 1 month reaches: 12, 12.3 and 15.2 % in respectively 8, 10 and 12 year olds, school leaders and other institutions should worry. Research to understand this phenomenon is desperately needed to uncover its real causes because of the drastic consequences on students’ learning and their capacity to cope with school environments. However, previous research (e.g., Arslan et al. 2011) has observed this phenomenon mostly among bullied children.

Despite the moderate psychometric performance of the BMSLSS and the PWI measures compared to the SLSS scales in this study, it has been confirmed that non-bullied students significantly outperform other children on all scales, in addition to overall happiness and overall satisfaction with life (OLS). In this latter the difference in the single item OLS has not been significant for the 10 year age group. Other consistent and significant differences in favour of non-victims concern: satisfaction with friends, with other children in class, safety at school and the freedom the child has (Table 4). The same trend is registered with regard to passive bullying. However, the differences in family factors are generally comparable in passive bullying. This could be a starting point for future research. For instance, parental style based on over protection is associated with increased bullying victimisation (e.g., Georgiou 2008).

One of the important findings of this research is that the two forms of bullying victimisation are significantly interrelated (p < .001), but the passive one remains more frequent in all the studied age groups. 15.1, 9.9 and 12.3 % of respectively 8, 10 and 12 year old students report being victims of active bullying, and 16.3, 15.8 and 20.6 % of respectively 8, 10 and 12 year old students being victims of passive bullying during the same period of 1 month (Table 2). This result is in agreement with past research worldwide. Despite the fact that researchers used different methods and time spans in measuring the prevalence of bullying. Our figures on victimisation seem much higher than those found in countries with comparable levels of development such as Turkey (Arslan et al. 2011) and certainly higher than the more developed countries, such as Norway (9.2 %) (Natvig et al. 2001). Yet, it will be highly informative if future research explores the wide array of passive bullying behaviours to target them, along with other forms of school violence in prevention programs.

In the first step, regression analyses echo earlier findings that satisfaction with life declines with age (e.g., Casas et al. 2014, Tiliouine 2014a, b) for both gender groups. It seems that as children grow older, they acquire more realistic views of life and its challenges. This in turn leads to more modest assessments of their general satisfaction with life. Results also show that passive bullying affects negatively satisfaction with life at a significant level (p < .005), but active bullying does not have such an effect (Table 6). This is indicative of the nasty consequences of the child being involved in unfriendly relationships with classmates. Past research has shown that victims of passive bullying usually lack social skills to manage their relationships with peers (e.g., Salmivalli 2010; Bradshow et al. 2009). Intervention programs should contribute in providing these victims with the needed social skills, such as social problem-solving, as protective factors. Social support from the school system partners would help create more favourable environments in schools.

However, it has been revealed in the second step of the regression that the selected life domains, with the exception of satisfaction with the school, have reduced the proportion of the explained variance in the first step. This trend suggests that beyond demographic variables, what matters most for satisfaction with life of children is the lack of rewarding material facilities, a gratifying living environment, good health, and self confidence. This trend has been noticed in Casas et al. (2014) and Casas and Rees (2015). Similar to Moore et al. (2012) assertions, global life satisfaction is unaffected when demographic variables are controlled for. The effect of life domains surpasses that of demographic differences and bullying experience when general life satisfaction is examined. Future studies should be more specific with relation to the type of bullying behaviours and mediating or moderating factors. Follow up studies with representative samples are highly recommended to examine these questions.

This research has many limitations. It is mainly an exploratory study, limited in time and space coverage and from which one cannot infer direct causal relationships. But at least, it shows that bullying is a very complex phenomenon that cannot be explained with one set of factors, rather all school settings and cultures, family factors and the socio-cultural organisation surrounding the child may contribute in its prevalence. For this, well informed theoretical models should be worked out in advance. Nevertheless, the drastic effects of bullying deserve to be a priority for researchers, policy makers and the whole social organisation, particularly in countries where quality education is sought as a powerful agent of social change.

References

Arseneault, L., Bowes, L., & Shakoor, S. (2010). Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: ‘Much ado about nothing’? Psychological Medicine, 40(05), 717–729.

Arslan, S., Savaser, S., & Yazgan, Y. (2011). Prevalence of peer bullying in high school students in Turkey and the roles of socio-cultural and demographic factors in the bullying cycle. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 78(8), 987–992.

Bacete, F. J. G., Perrin, G. M., Schneider, B. H., & Blanchard, C. (2014). Effects of School on the Well-Being of Children and Adolescents. In Handbook of Child Well-Being (pp. 1251–1305). Springer Netherlands.

Barboza, G. E., et al. (2009). Individual Characteristics and the Multiple Contexts of Adolescent Bullying: An Ecological Perspective. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(1), 101–121.

Boulton, M. J., Murphy, D., Lloyd, J., Besling, S., Coote, J., Lewis, J., & Walsh, L. (2013). Helping counts: predicting children’s intentions to disclose being bullied to teachers from prior social support experiences. British Educational Research Journal, 39(2), 209–221.

Bousenna, M., Tiliouine, H., Lakhdar, B., & Zahi, C. (2009). Analyse de la situation du système éducatif algérien (Rapport). Alger: UNICEF.

Bradshow, C. P., Sawyer, A. L., & O’Brennan, L. M. (2009). A Social Disorganization Perspective on Bullying-Related Attitudes and Behaviors: The Influence of School Context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 43(3–4), 204–220.

Carbone-Lopez, K., Esbensen, F. A., & Brick, B. T. (2010). Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: Gender differences in direct and indirect forms of bullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 8(4), 332–350.

Casas, F. & Rees, G. (2015). This issue of Child Indicators Research

Casas, F., Tiliouine, H., & Figuer, C. (2014). The Subjective Well-being of Adolescents from Two Different Cultures: Applying Three Versions of the PWI in Algeria and Spain. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0229-z.

Cummins, R. A., & Lau, A. L. (2005). Personal Wellbeing Index – School Children. Manual (Third Edition). Melbourne: School of Psychology, Deakin University

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: _ree decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

Elamé, E. (2013). Discriminatory Bullying: A New Intercultural Challenge. Springer.

Georgiou, S. N. (2008). Parental style and child bullying and victimization experiences at school. Social Psychology of Education, 11(3), 213–227.

Goswami, H. (2012). Social relationships and children’s subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 107(3), 575–588.

Helliwell, J. F., and Barrington-Leigh, C. (2010). Measuring and Understanding Subjective Well-being in NBER Working Paper No. 15887, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Jacobson, R. B. (2007). A lost horizon: the experience of another and school bullying. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 26(4), 297–317.

Koo, H. (2007). A time line of the evolution of school bullying in differing social contexts. Assia Pacific Education Review, 8(1), 107–116.

Lakhdar, B., Ameyeoud, A., Benazouz, L., Bourouina, Y., Boussena, M., Chenennou, M., Guitani, B., Tiliouine, H., Tounsi, M. & Zahi, C. (Octobre, 2012). Elaboration d’un référentiel d’indicateurs d’évaluation des normes assignées au système scolaire algérien, UNICEF-INRE, Alger (http://www.inre-dz.org/documents/docrevue/Revue%20BLr_opt.pdf, downloaded 9th January, 2014)

Ministère Délégué Chargé de la Famille et de la Condition Féminine. (2008). Plan National d’Action pour les enfants 2008–2015. Alger

Moore, P. M., Huebner, E. S., & Hills, K. J. (2012). Electronic bullying and victimization and life satisfaction in middle school students. Social Indicators Research, 107(3), 429–447.

Natvig, G. K., Albrektsen, G., & Qvarnstrøm, U. (2001). School-related stress experience as a risk factor for bullying behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30(5), 561–575.

Olweus, D. & Breivik, K. (2014). Plight of Victims of School Bullying: The Opposite of Well-Being. Handbook of Child Well-Being (pp 2593–2616), Springer Netherlands

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Oxford: Blackwell.

Pryce, S., & Frederickson, N. (2013). Bullying behaviour, intentions and classroom ecology. Learning Environments Research, 16(2), 183–199.

Salmivalli, C. (2010). Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggressive and violent behavior, 15(2), 112–120.

Seligson, J. L., Huebner, E. S., & Valois, R. F. (2003). Preliminary Validation of the Brief Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS). Social Indicators Research, 61(2), 121–145.

Tiliouine, H. (2014). Islamic education and youth well-being in Muslim countries, with a specific reference to Algeria. In Handbook of Child Well-Being (pp. 1209–1226). Springer Netherlands.

Tiliouine, H. (2014a). Application of the Personal Well-being Index with Algerian secondary school students. Michalos, A. (Editor). In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, Springer Netherlands

Williams, L. M., & Peguero, A. A. (2013). The Impact of School Bullying on Racial/Ethnic Achievement. Race and Social Problems, 5(4), 296–308.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tiliouine, H. School Bullying Victimisation and Subjective Well-Being in Algeria. Child Ind Res 8, 133–150 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9286-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-014-9286-y