Abstract

In this paper, we ask whether there are Canada/U.S. differences in the extent to which children who were rich versus poor during their early years have developed differences in outcomes by the time they reach adolescence or early adulthood. Using comparable longitudinal data for each country, separate analyses are first conducted for rich compared to poor children living in Canada and rich compared to poor children living in the United States. We then pool data sets to test whether any rich/poor child outcome gaps that have emerged are greater (or smaller) in Canada compared to the U.S. Our data source for Canada is the Statistics Canada National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth and for the U.S. we use the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 79, Child-Young Adult supplement. Key findings include: 1) rich child/poor child outcome gaps are evident for all outcomes in both countries; 2) larger gaps between rich and poor children are evident in the U.S. for math scores and high school completion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In this paper, we adopt a Canada-US comparative research strategy to study emerging gaps in the outcomes of rich and poor children which may be important for understanding the transmission of economic status across generations. This is an important policy issue, not only if we care about equality of opportunity, but also if we care about potentially under-developing the human capital of some children and so reducing future productivity.

A large literature links family socioeconomic status and early developmental outcomes for children that are predictive of economic (and other) outcomes later in life (see Almond and Currie 2011a; Cunha and Heckman 2009; or Currie 2009 for recent reviews). Links from family income to child well-being have been found to extend back as far as ‘in utero’ development (e.g., Almond and Currie 2011b; Currie 2011).

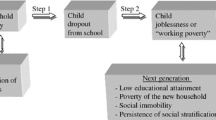

Such work suggests that income inequality begins to regenerate itself very early in life as children from lower-income families fall behind children from higher-income families in outcomes predictive of future economic well-being. Although there has, in the past, been more research attention on the child outcome deficits associated with child poverty (see Brooks-Gunn and Duncan 1997 for a review), an important point is that it is not just that poor children lag others, but also that rich children have better outcomes than others. For example, research has documented full socioeconomic 'gradients' in health outcomes for children (e.g., Case et al. 2002 for the U.S.; Currie and Stabile 2003 for Canada). These studies indicate, moreover, that differences in child outcomes by family socioeconomic status both appear early and cumulate over time.Footnote 1

Not surprisingly, then, the literature on intergenerational earnings mobility demonstrates strong correlations between parental earnings and children’s earnings after they too have become adults, but the degree to which economic status is passed on to children differs across countries. For example, Corak (2006) reports that nearly half of U.S. children born to low-income parents become low-income adults; about a third of Canadian children born to low-income parents themselves become low-income adults. For adults, such differences in intergenerational mobility can plausibly be attributed, for example, to differences in the return to human capital or differences in labour market institutions. Of course, this cannot explain the socioeconomic gradients in outcomes for children, while still children.

Comparative research that exploits cross-country differences is a potentially useful way to understand processes underlying early stages in the intergenerational transmission of economic status.Footnote 2 Smeeding et al. (2011) suggest that comparisons across countries with different levels of inequality as well as different public policies and institutions, can exploit, in a sense, 'natural experiments' that are not so readily available if we confine ourselves to single-country studies. That is, if two countries differ in the magnitude of rich/poor gaps in family-level resources, we might expect to find cross-country differences in the magnitude of rich/poor child outcomes gaps. Or, if differences in family resources are more persistent over time in one country than another, then they may have stronger associations with child outcomes.Footnote 3 Finally, if two countries differ in terms of public policies and institutions, the degree to which the long-term consequences of coming from a low-income family are mediated may differ.

Some recent research uses a comparative strategy to help understand the emergence of inequality in child outcomes. For example, Bradbury et al. (2012) study readiness to learn for 4/5 year olds in Australia, Canada, the UK and the U.S. Corak et al. (2011) study health, cognitive development, and readiness to learn for 0–13 year olds in Canada and the U.S. Waldfogel and Washbrook (2011) study cognitive and behavioural outcomes for children up to 5 years of age in the U.S. and the U.K. We add to the comparative literature on emerging inequality, using comparable longitudinal data for Canada and the U.S., to study the extent to which children who were poor versus rich during their early years have developed differences in educational outcomes by the time they reach adolescence and early adulthood.

We have chosen to focus on differences in educational attainments since an extensive literature has shown that education is particularly important for future earnings (see Black and Devereux 2011 for a recent review). In view of the recent literature emphasizing the importance of both cognitive and non-cognitive skills (e.g., Cunha and Heckman 2009), we also study differences in children’s motivations. Aspiring to a high level of education may be very important for educational success and subsequent earnings. Fortin et al. (2012) demonstrate, for example, that changing educational motivations among young adolescents are the most important factor in explaining the gender gap in high academic achievement that has emerged in the U.S. Specifically, then, for early adolescents (12 to 15), we compare differences in self-reported educational aspirations for children who were rich versus poor as pre-schoolers (2 to 5) as well as differences in math scores. For young adults (19 to 21), we compare differences in completion of a high school diploma and enrolment or completion of post-secondary education for children who were rich compared to poor as children (9 to 11), though we cannot trace family income back as far as the pre-school years. Our data span the years 1994 through 2008; thus, our findings reflect policies and economic conditions prevailing during that period of time.

1.1 Policy Differences

Many scholars (e.g., Esping-Andersen 1990) categorize Canada and the U.S. as having very similar welfare states, and, indeed, the general social context is sufficiently similar to make comparisons highly relevant. For example, both countries are affluent, industrialized, geographically large and have ethnically diverse populations due in part to histories of immigration. Both countries have developed ‘liberal’ welfare states, characterized by Esping-Andersen (1990) as having a smaller role for the state than characterizes many European countries, for example. At the same time, however, there are also some important policy and institutional differences between Canada and the U.S. that may affect the incidence of child poverty, the duration of child poverty and the extent to which coming from a poor background leads to poor educational outcomes.

Both Canada and the U.S. offer income-tested benefits for families with children. In Canada, there is a basic ‘Canada Child Tax Benefit’ (CCTB) of roughly $1000 per child per year which, though income tested, is still received by 80 % of families with children. The CCTB is a tax-free, monthly cash benefit that increases with number of children and falls with income. An additional 40 % of lower-income families also receive a National Child Benefit Supplement which is of maximum value for lowest income families (i.e., families in the bottom quintile of the income distribution). The programme was re-structured to its present form in 1998. The maximum benefit for a two-child family (in current dollars) increased from $2,540 annually in 1995–1996 to $5,222 in 2004–05 (HRSDC 2010), largely through expansion of the NCB Supplement component. Lower-income parents who are recipients of Employment Insurance also receive a ‘family supplement’ to their benefits.

The U.S. does not have a cash transfer programme that is available for most families with children (i.e., like the Canadian CCTB). However, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a programme to assist working poor and near-poor families with children (more like the Canadian NCB supplement). Benefits are higher for families with 2 or more children than for families with only one child. Benefits are paid only once in the year, at tax time, and in fact, many families do not actually receive a cheque in the mail, but rather a reduction in taxes owing. As is true for the CCTB, maximum EITC benefits have increased substantially, from $953 in 1991 to $4824 by 2008 (Danziger and Danziger 2010).

Near the beginning of our study period, major cuts to social assistance for single mothers took place in the U.S. with the 1996 ‘Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconcilation.’ Single mothers not searching for paid work could be sanctioned by the termination of benefits (Danziger and Danziger 2010). No equivalent change to social assistance benefits took place in Canada, where anyone in ‘need,’Footnote 4 including couples with children, can be eligible for benefits.

Another important difference between the countries is that Canada offers cash maternity/parental benefits. In the time period relevant for our study, eligible new parents could receive up to 26 weeks of leave paid at 55 % of previous earnings (though with a ceiling on insurable earnings of roughly median male earnings). No equivalent programme exists in the U.S.

Overall, then, Canada has a more redistributive tax/transfer system than the U.S. (see also Bradbury et al. 2012). Data from the Luxembourg Income Study 2012 reflecting our study period indicate, for example, that while market income poverty rates for the two countries were fairly similar (21.1 % in Canada and 22.8 % in the U.S.), post-taxes and transfers, the poverty rate falls more in Canada (to 13.3 % versus to only 17.4 % in the U.S.). More inequality in the distribution of family level resources in the U.S. might plausibly contribute to more inequality in outcomes for children.

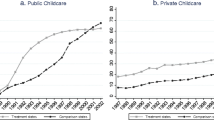

Social institutions and policies can also play a mediating role between family income and child outcomes. In particular, public health insurance is available in Canada which should help mediate the negative consequences of a health shock for subsequent development of the child, though Currie and Stabile (2003) do still find a socioeconomic gradient in Canada. There is also some evidence that the Canadian school system is more egalitarian. For example, Fig. 1 indicates a much steeper socioeconomic gradient in private school attendance for 10 to 17 year-old children in the U.S. than in Canada. While roughly the same fraction of children from lower-income families 10 years earlier attend private schools in the two countries (3.8 % in Canada and 3.3 % in the U.S.), private school attendance is dramatically more likely for U.S. children from higher-income backgrounds (21.6 % compared to 9.7 % in Canada). Thus, the probability of attending a private school for a high-income child is almost 8 times the probability for a lower-income child in the U.S. versus only about 3 times for Canada.Footnote 5 These findings indicate, at the very least, that in the U.S. children from rich compared to poor backgrounds have very different educational experiences. Moreover, to the extent that rich parents self select out of public schools, this may exacerbate positive/negative peer externalities.

Corak et al. (2011) present descriptive evidence that children (aged 0 to 11) in more vulnerable families (e.g., poor or lone-parent) do, in fact, fare better in Canada than in the U.S. across a variety of outcomes. For example, vulnerable children in Canada have better mother-assessed mental health, over-all health, and fewer hospitalizations, and they are less likely to be doing badly at school than their counterparts in the U.S. (Corak et al. (2011). Bradbury et al. (2012) find steeper socioeconomic gradients in pre-school vocabulary and externalizing behaviour scores in the U.S. than in Canada.

We contribute to these studies in 3 important ways: a) by using longitudinal data that allows us to track family income back into early childhood; 2) by using a ‘difference in difference’ multivariate empirical strategy (Corak et al. 2011 is descriptive); 3) by looking at outcomes for adolescent children and young adults (Corak et al. 2011 looked at outcomes for children aged 0 to 13; Bradbury et al. 2012 studied outcomes for pre-school children).

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the data. Section 3 outlines the methods while Section 4 discusses estimation results. Section 5 summarizes and concludes.

2 Data

Perhaps the most challenging task for our project was to construct comparable longitudinal samples of adolescents for whom we can track family income many years back into childhood. Our data source for Canada is the Statistics Canada National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth and for the U.S. we use the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 79, Child-Young Adult supplement. Both surveys provide longitudinal data with information about family income and child outcomes. To construct comparable Canada/U.S. samples, we follow a ‘lowest common denominator’ approach. The U.S. NLSY data set was originally designed to follow U.S. youth who were aged 14 to 21 on December 31, 1978. NLSY respondents who later became mothers were then surveyed about their children, who are the focus of our interest here. The original age restriction for the NLSY sample thus imposes an age restriction on the mothers we observe (i.e., they must be between 30 and 37 in 1994); we are also limited to cases where the biological mother is the survey respondent. In the Canadian NLSCY, the child rather than the parent is the main focus of the survey which began in 1994 with a representative sample of the child population aged 0 to 11 years. Since there is no restriction on mother age in the NLSCY, we impose the mother age restriction from the NLSY on the Canadian data and limit our attention to households where the biological mother is present.

A further restriction in the U.S. data is that there are very few immigrant families (since the mother had to be present in the U.S. during her youth in order to be part of the original NLSY sample). We thus exclude immigrant families from both surveys. In the Canadian data set, military families are not included; hence, these observations are dropped in the U.S. data. Since the NLSCY only carries out surveys every 2 years, our analyses follow the same pattern.

Adults (mothers in the case of the U.S. or ‘persons most knowledgeable’ in the case of Canada) provide most of the information about the family used for our analyses. In particular, adults provide the data about family income, family composition, parental education and labour market experiences, etc.

Children are not survey respondents in either Canada or the U.S. while they are young. However, in both the NLSCY and NLSY children begin to respond to their own questionnaire from the age of 10, and we use child-reported data for some of the outcomes we study (see below). In Canada, with parental permission, children complete a pen and paper survey. The survey is completed in privacy and returned to the interviewer so that parents do not see the child’s answer. In the U.S., depending upon question and age group, interview method can vary. We provide details in relevant sections below.

Both the NLSY and NLSCY provide longitudinal sampling weights which are employed in all of our analyses; we use the longitudinal weights from the final cycle, which, according to Statistics Canada, ensures that the longitudinal sample is representative of the original starting population (Statistics Canada 2008). Appendix 1 illustrates considerable attrition in our samples. Thus, although the longitudinal weights should account for attrition, including differential rates of attrition for different demographic groups, we also re-estimate all models using the inverse probability re-weighting procedure proposed by Wooldridge (2002) to address this problem; see Appendix 1 for details. Reassuringly, no substantive conclusions are affected.

In cases where we pool data for the two countries, weights are standardized so that the sum of within-country weights is equal to one. Although we take care not to include the same child twice, we do have sibling observations in both data sets. Thus, we adjust for clustering by mother’s id for the U.S. and by household id for Canada.

2.1 Child Outcome Variables

Given some inevitable limitations in a cross-country comparison, we have, nonetheless, been able to construct a set of indicators which seem both important from the perspective of re-producing income inequality in the next generation as well as reasonably comparable in terms of wording of questions and ages of children asked.Footnote 6 We begin with educational aspirations and math scores at roughly ‘junior high’ age, then move on to consider educational attainments at early adulthood (not having completed high school; having enrolled in post-secondary education). Details are provided below.

2.2 Educational Aspirations

Adolescents (aged 12 to 15) from both countries answer a question about their education aspirations. For Canada, educational aspirations were recorded on a paper questionnaire. For the U.S., respondents (12–15 years old) were interviewed differently for different age groups. Those 15 years old were considered ‘young adults’, thus they were interviewed primarily by telephone. Those 12–14 years old answered the aspiration question in the Self-Administered Supplement. This component was administered as a paper booklet in 2000, on hand-held personal data assistant (PDA) and on laptop in 2002 and 2004, and on laptop only in 2006 (Bureau of Labor Statistics (2009)).

Based on categorical responses to the educational aspirations question, a set of dichotomous dependent variables indicating different aspiration levels are defined. The wording of the Canadian question is: ‘How far do you hope to go in school?’ For the U.S. 12–14 year olds, the question is: ‘How far do you think you will go in school?’ For U.S. 15 year olds, the question is: ‘What is the highest grade or year of REGULAR school, that is, elementary school, high school, college, or graduate school that you would LIKE to complete?’ Given our interest in emerging income inequality, it is of interest to compare percentages of affluent and non-affluent children who have ‘low’ compared to ‘high’ educational aspirations. We define ‘less than high school’ or ‘just high school’ as having ‘low’ aspirations; we define ‘more than one university degree’ as having ‘high’ aspirations.Footnote 7

2.3 Math Scores

Based on a math test administered to the youth at home, the Canadian NLSCY provides a classical scaled math score. This math test is made up of 20 computational questions. It is a shortened version of the Mathematics Computation Test of the second edition standardized Canadian Achievement Tests. ‘The CAT/2 mathematical operations test measures the student's ability to do addition, subtraction, multiplication and division operations on whole numbers, decimals, fractions, negatives and exponents. Problem solving involving percentages and the order of operations are also measured.’ (pp.148, Statistics Canada (2005)) The level of test is determined by the child’s grade or by age if grade is unknown. The classical scaled math score is derived from national standards established by the Canadian Test Centre (CTC) in 1992 using a Thurstone procedure (Statistics Canada 2005, 2008).

In the U.S. case, the NLSY provides an age-specific standard math score derived from percentile score, which is in turn derived from the raw score. The math test used here is a sub-component of the Peabody Individual Achievement Test (PIAT), which is ‘among the most widely used brief assessment of academic achievement having demonstrably high test-retest reliability and concurrent validity’ (pp. 94, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2006)). The math sub-component includes 84 multiple-choice questions. It tests skills from recognizing numerals and to advanced concepts in geometry and trigonometry (Bureau of Labor Statistics (2006)).

Given concerns about lack of comparability in math tests, we focus simply on having a score that is ‘less than average’ (bottom two quintile) or having a score that is ‘better than average’ (top two quintiles), compared to all children who wrote the test (not just the rich and poor children in our sample).Footnote 8

2.4 Educational Attainment

Young adults themselves report educational attainment in both countries. Two dependent variables are used here: a) not finishing high school; and b) enrolling in (or completing) post-secondary education. ‘Dropout’ is a dummy variable coded 1 if the youth has not completed high school by age 19–21 and is not currently enrolled in school. ‘Postsecondary’ is a dummy variable coded 1 if the youth is currently enrolled in a postsecondary institution or has completed some postsecondary education by age 19–21.

2.5 Family Income

Our measure of family income is annual income from all sources, post-transfer but pre-tax. In Canada, mothers are asked ‘What is your best estimate of your total household income from all sources in the past 12 months, that is, the total income from all household members, before taxes and deductions?’Footnote 9 Data are not top-coded in the master files of the NLSCY that we use here. U.S. mothers report their household’s income from 19 different categories including items such as wages and salaries, military income, business income, farm income, transfers from government sources, and transfers from non-government sources.Footnote 10 The total household income is a constructed variable that sums up income from these various sources (Bureau of Labor Statistics (2008)). To capture economies of scale within households, ‘equivalent income’ is calculated by dividing total household income by the square root of household size. All analyses of income levels are made in 2003 U.S. dollars. Nominal incomes from other years are converted to 2003 real values using country-specific Consumer Price Indices (CPI’s). Canadian incomes are converted to U.S. dollars using the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) index for 2003.Footnote 11

2.6 Some Caveats

We are not able to compare all outcomes for the same sample of children. Some outcomes are only available for older adolescents and young adults (e.g., post-secondary enrolment) whereas others (e.g., educational aspirations) are only asked of younger children. The NLSCY has not been running long enough to be able to follow one set of children all the way from pre-school years to early adulthood (the survey started in 1994 with a sample of children then aged 0 through 11). Thus, for high-school completion and post-secondary attainment, the best we can do is use ‘family income position 10 years ago’ which thus refers to family income when the child was 9 through 11. Also, since small sample size is especially limiting in this work, where possible we pool observations from different cycles of data. A further limitation imposed by sample size is that we are not able to provide separate estimates for boys and girls. Appendix 2 provides details for each outcome variable.

3 Empirical Methods

The first goal of our analysis is simply to document differences in outcomes likely to be relevant for the future economic well-being of adolescents and young adults who were members of ‘rich’ compared to ‘poor’ families 10 years earlier. Using the comparable longitudinal data files, we first do this separately for both Canada and the U.S. Within each country, our aim is to study early stages in the process of transmission of economic status from one generation to the next. By looking back 10 years from the adolescent or young adult outcomes, we are allowing time for part of the story to have unfolded.

We operationalize ‘rich’ very simply as having had family equivalent income in the top quintile (richest 20 %) for children of the same age and country 10 years ago; ‘poor’ is analogously defined as having had family equivalent income in the bottom quintile (poorest 20 %). While we focus in the main body of our analysis on this relative concept of income difference which we feel is most appropriate for a study of emerging inequality, we have also carried out all analyses using the same equivalent income cut-off points for both Canada and the U.S. For example, we use purchasing-power-parity adjusted Canadian quintile cut-off points for the U.S. or purchasing-power-parity adjusted U.S. cut-off points for Canada. These are discussed at the end of Section 4.

For each outcome studied, we then follow the same procedure. We select children with the requisite child outcome data whose family equivalent income during their early years placed them in either the bottom or the top quintile of the relative income distribution. We do this in order to sharpen the focus on inequality generation, though we do also later present results comparing children at the top/bottom to those from the middle of the income distribution. This estimation strategy is similar to the recent work of Waldfogel and Washbrook (2011) who estimate rich/poor gaps in pre-school outcomes for the United Kingdom and the United States, or Bradbury et al. 2012, which adds Canada and Australia to estimate rich/poor outcome gaps, again focusing on pre-school outcomes.

To estimate whether statistically significant differences in child outcomes between rich and poor children have emerged during the next 10 years between, for example, pre-school and early adolescence, we estimate simple regression modelsFootnote 12 of the following form for the pooled samples of cycle 1 top equivalent income quintile children and cycle 1 bottom equivalent income quintile children:

Where: Y ij refers to outcome i for child j; α i is the mean outcome for children from the top quintile in the first period; βi measures the difference between children from the bottom and children from the top quintile. A statistically significant estimate for β i is evidence, within countries, that adolescent outcome gaps have emerged between children from rich versus poor families during their pre-school years (or between middle childhood and young adulthood, as relevant).

To assess whether the size of these outcome gaps is larger (smaller) in Canada compared to the U.S., we pool the Canada and U.S. samples and estimate the following models for each child outcome, i:

Where: USj is a dummy variable = 1 for child j from the US and BottomQuintile1j X USj is an interaction term. A statistically significant estimate for β 2i will indicate a Canada/U.S. difference in the rich/poor gap that has emerged 10 years later; smaller if β 2i is negative and larger if β 2i is positive.

An important next step is to control for other ‘risk factors’ that may be pathways from low (or high) income status to child outcomes. For example, family structure is one of the most important correlates of family income position (see Burton et al. 2012 or Picot et al. 1999). Children from lone-parent families may have lower educational attainments because they have low income and/or because lone parents may be more stressed, have less time to spend helping with homework, etc. Adding a vector of ‘early life risk factors’ to our within-country rich compared to poor child outcome regressions allows us to ask if relative economic background plays a role in explaining rich-child/poor-child outcome gaps even after we have controlled for vulnerable circumstances correlated with income.

Controlling for risk factors, we now estimate:

where Y ij again refers to outcome i for child j and X j refers to a vector of early-life risk factors, described below.

Finally, we again pool the data from Canada and the U.S. in order to test whether the rich child/poor child gap is significantly larger (smaller) in the U.S. compared to Canada after also controlling for risk factors by estimating, for each child outcome, i:

It is particularly important to control for these 'risk factors' in the pooled regressions since past research (Corak et al. 2011) has emphasized that these also differ between Canada and the U.S.—with families in the U.S. experiencing more 'risks' (e.g., lower education, more lone mothers, larger families, younger mothers). While within country analysis is relatively straightforward, data size and comparability issues unfortunately limit our selection of ‘risk factor’ variables. In general, these pertain to the mother, 10 years before the current child outcome was assessed. We control, first, for the mother’s age at the child’s birth, since very young mothers may be more economically vulnerable, for example.Footnote 13 A second important risk factor, limiting resources of both time and money, is family structure. For both Canada and the U.S., we add a ‘lone mother’ dummy variable if the mother did not have a spouse or partner at the time of interview (i.e., we do not rely on legal marital status). Mother’s education level is modelled with two dummy variables: less than high school or with college or university degree.Footnote 14 Finally, we include two indicators of mother’s labour market attachment 10 years ago. First, we include mother’s weekly work hours. For the U.S., this is total number of hours worked divided by total number of weeks worked in past calendar year. For Canada, this variable is the mother-reported usual weekly hours in the past 12 months. Second, we flag mother’s experience of unemployment in the past 12 months (Canada) or in the past calendar year (U.S.).

We also control number of siblings 10 years ago. For both countries, this includes siblings of all ages and includes all full, half, step, adopted and foster siblings of the child. We also note if the child is first born. For the U.S. sample, this variable is coded 1 if the birth order of the child is 1. For the Canadian sample, this variable is coded 1 if the child did not have any older siblings (including full, half, step, adopted and foster siblings) living in the household. This may not exactly be the child’s birth order if an older sibling of the child born to the same mother was not living in the same household or if the child had any older siblings who lived in the same household but were not born to the same mother.Footnote 15

We also control for child gender and age since both are relevant for child outcomes. For both countries, child age is age as of December 31st of the survey year 10 years prior to the survey year in which the relevant outcome was measured. Finally, in some specifications, we also add regional controls (Atlantic, Quebec, Prairie and Alberta/BC for Canada and Northeast, South and West for the U.S. with Ontario as base).

3.1 Descriptive Results

In the interests of space, we do not report risk factor means for each of the many samples of children studied. But, to provide a summary comparison of differences in risk factors for children in the top versus bottom of family equivalent income distributions in Canada and the U.S., Table 1 reports means for children currently ‘older’ (10 to 17) who would have been ‘younger’ when they were 0 to 7. In Canada, while mother’s age at child’s birth and family size are fairly similar between bottom and top quintile children, dramatic differences are evident for all other risk factors. Education levels are much lower (23.4 % of bottom quintile mothers have less than high school compared to 1.4 % of top quintile mothers); lone-parenthood is much more likely (37.1 % are lone parents in the bottom compared to 1.4 % in the top); weekly paid hours are lower (10 per week compared to 25.5); unemployment is more likely (20 % of bottom quintile mothers experienced unemployment during the last year compared to 4.2 % of top-quintile mothers).

Similar patterns are apparent when we compare bottom and top quintile mothers in the U.S. Some differences in top/bottom quintile differences in family circumstances between the countries are also interesting to consider. For example, mothers in the bottom quintile of the U.S. distribution are, on average, 3.6 years younger than those in the top (whereas there is only a 1 year difference in Canada). Lone-parenthood is particularly more likely for U.S. bottom quintile families (55.3 % versus 37.1 % in Canada). On the other hand, differences in weekly paid hours for top compared to bottom quintile mothers are smaller in the U.S. than Canada, mostly because mothers from the bottom quintile of the U.S. income distribution do twice as many paid hours as Canadian mothers from the bottom of the distribution.

4 Estimation Results

Unconditional differences in child outcomes for rich and poor children are illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3, for Canada and the U.S., respectively. In both Canada and the U.S., emerging rich-child/poor child gaps are apparent for all outcomes studied. This is consistent with the extensive body of research linking family income and child outcomes discussed earlier. In terms of cross-country differences in outcomes gaps, Fig. 4 illustrates relatively small Canada/U.S. differences in aspirations of junior-high students; however, larger differences in relative math scores and later educational attainments are apparent with the differences between rich and poor children generally smaller in Canada. The following sections discuss the findings of this paper in more detail.

4.1 Aspiration Differences for Adolescents Who Started Life in Rich Compared to Poor Families

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate that in both Canada and the U.S. by ages 12 to 15, children who started life in poor families already have more limited educational aspirations than children from rich families. They are more likely to plan to drop out or just to finish high school (15 percentage points higher in Canada; 13.8 percentage points higher in the U.S.). They are much less likely to aspire to more than one degree or a professional designation (17.8 points less likely in Canada; 14 points less likely in the U.S.). Columns denoted ‘A’ in Tables 2 and 3 report average marginal effectsFootnote 16 calculated from probit estimates for specification (1) above. These estimates confirm that, unconditionally, there are statistically significant differences in the educational aspirations of 12 to 15 year-old children from rich compared to poor children within both countries.

Average marginal effects from equivalent regressions, with early-life risk factors included, are reported in columns marked ‘B’ in Tables 2 and 3.Footnote 17 For both Canada and the U.S., the difference between rich and poor children in the likelihood of aspiring to no more than a high school education disappears when we account for individual and household-level characteristics (see Table 2). For the U.S., the difference between rich and poor children in aspiring to very high levels of education also disappears when we account for child and household characteristics (see Table 3). However, for Canada, although the size of the association falls (from −17.8 percentage points without controls to −10.2 percentage points with other risk factors included in the model), poor children continue to be less likely than rich children to have very high educational aspirations.

What about cross-country differences in the extent to which pre-school family income predicts rich/poor gaps in the probability of the young adolescent planning to stop his/her education at the high school level (or less)? Table 2 again indicates a significantly smaller gap in educational aspirations between U.S. children from rich compared to poor early-life backgrounds than is evident between Canadian children from rich compared to poor backgrounds. These findings are robust to the inclusion of regional controls (see column C).

4.2 Math Score Differences for Adolescents Starting Life in Rich Compared to Poor Families

Figures 2 and 3 next illustrate gaps in relative math scores for children now 12 to 14 whose families were poor when the children were 2/4, compared to the scores for children whose families were rich when they were 2/4. In Canada, over half of children with low-income backgrounds have ‘less than average’ math scores whereas only a third of children with high-income backgrounds have ‘less than average’ scores, a rich child/poor child gap of 21 percentage points. The same pattern is evident in the U.S., where there is a 38.3 percentage point gap. Tables 4 and 5 reports average marginal effects from the estimated probit models. Results show that both within-country rich-child/poor child math score differences are statistically significant, unconditionally (see column A’s). When we control for other child and family risk factors, including mother’s education level, Tables 4 and 5 (column B’s) shows that the gap remains statistically significant in both countries, though the size of the association falls. This is particularly true for the U.S., where the estimated marginal effects show poor children to be 38.3 percentage points more likely than rich children to have poor math scores versus 14.0 percentage points when risk factors are added to the model. Footnote 18

The pooled estimates indicate that the magnitude of the rich-child/poor-child relative math score gap is significantly larger, all else equal, in the U.S. than in Canada (see Tables 4 and 5, Canada/U.S. pooled, specifications A-C). That is, the gap between rich and poor children in the U.S. is between 16 and 21 percentage points (depending on specification) larger in the U.S. than Canada. This seems a potentially very policy relevant finding that warrants further research attention. What is it about being born a low-income child in the U.S., other than family and child-risk factors, that leads to more falling behind in math relative to rich children than we observe in Canada? Possibilities could include greater use of elite private schools or tutors by the rich in the U.S.; or, greater intervention/remediation in public schools in Canada?

4.3 Educational Outcome Differences for Adolescents from Rich Compared to Poor Families Completing High School

Large gaps in rates of self-reported high school completion between children from rich and poor families are evident in both Canada and the U.S (see Figs. 2 and 3). This fact is particularly disturbing in an era when education is increasingly important for future economic outcomes. In Canada, 23.6 % of youth aged 19 to 21 from disadvantaged economic backgrounds 10 years earlier have neither completed a high school diploma nor are currently enrolled in any form of educational programme compared to 6.5 % of young people from advantaged backgrounds. An even higher 29.7 % of youth from disadvantaged backgrounds in the U.S. have ‘dropped out,’ though dropping out is rare for youth from affluent families (only 2.5 %).

Table 6 indicates that both within-country gaps are highly significant, unconditionally. However, Table 6 suggests that in Canada, the relationship between early-life family income and the probability of completing high school disappears after we control for early-life risk factors; this is not the case for the U.S. where young adults from families with low-income during their early years are 16 percentage points more likely than their affluent peers to have dropped out of high school.

The cross-country comparison reported in the final three columns of Table 6 indicates that the rich/poor gap in high school completion is around 14 percentage points larger in the U.S. than Canada, after controlling for child and family risk factors. This again seems a very important, policy-relevant difference between the two countries that warrants further, more detailed investigation into difference in educational systems between the two countries.

4.3.1 Enrolment in Post-Secondary Education

A more encouraging number is that 54 % of Canadian youth from low-income families at age 9/11 are enrolled in some form of post-secondary education at age 19/21, though this is still much lower than the 84 percent post-secondary enrolment rate for Canadian youth from affluent families (see Fig. 2). Self-reported post-secondary enrolment rates are lower over-all in the U.S. than in Canada, and a 40 percentage point rich-child/poor-child gap is evident. Frenette (2005) also finds that low-income youth are less likely to enrol in post-secondary education in the U.S. than in Canada.

Table 7 indicates statistically significant unconditional gaps in the probability of post-secondary enrolment in both countries.Footnote 19 Controlling for early life risk factors again fully mediates the unconditional relationship between early family income and the probability a young adult will be enrolled in (or have completed) post-secondary education in Canada. In the U.S., controlling for these risk factors substantially reduces but does not eliminate the difference. Without risk factors, poor children are 40.6 percentage points less likely than rich children to be enrolled in post-secondary education; with risk factors, the gap falls to 15.6 percentage points). No cross-country difference in the rich-child/poor child post-secondary enrolment gap is evident.Footnote 20

4.4 Sensitivity Analyses

We have focused above on a relative definition of children who are economically advantaged compared to disadvantaged within their own country (i.e., by choosing to compare the poorest 20 % of children to the richest 20 % of children). However, since income inequality is higher in the U.S. than Canada, it is true that the absolute value of the income difference between rich and poor children is larger in the U.S. For example, mean equivalent real family income in the final cycle for children who started out, 10 years earlier, in the top quintile is $69,162 in the U.S. but only $50,583 in Canada (both figures are 2003 USD and the difference is statistically significant); whereas, the mean equivalent income for children who started out at the bottom of their respective country income distributions have more similar real incomes 10 years later ($20,223 in Canada and $19,342 in the U.S. which is not a statistically significant difference).

To see if our results are driven by the fact that the rich in the U.S. are much richer than the rich in Canada, this section repeats the analyses from above using U.S. cut-off points for Canada. Table 8 reports only the coefficient for the U.S.X Bottom Quintile Cycle 1 interaction term obtained from the estimation of Eq. 2 above.Footnote 21 The important conclusion of Table 8 is that the pattern of cross-country differences reported earlier is unchanged if we define quintiles in both countries using the U.S. cut-off points.

4.5 What About Children from Middle-Income Families?

All analyses have also been carried out including children from families with incomes 10 years ago in the middle income quintile compared to those at the bottom and those at the top. Results are summarized in Table 9. Not surprisingly, there are not as many differences between children from the middle and bottom; or, between children from the middle and the top income quintiles as were evident between the top and bottom. Still, junior-high age children from high-income families are less likely than those from middle-income families to have low educational aspirations. In Canada, lower-income children are also less likely than middle-income children to aspire to more than one university degree, though this does not seem to be the case in the U.S. There is no statistically significant difference in the probability of having very high educational aspirations between middle and high-income children in either country.

In terms of relative math scores, the most striking point to take from Table 9 is that while we do not generally see differences between the middle-income children and others in terms of math scores, children from the top of the U.S. income distribution perform very well. The same point is true with respect to dropping out of high school. Differences are not generally apparent, except that high-income children in the U.S. are very unlikely to have dropped out. The relative advantage of children from high-income U.S. families is consistent with Bradbury et al. 2012 who find that pre-schoolers from high-income families in the U.S. do particularly well.

4.6 Stickiness of Income Position?

One explanation for our finding of bigger differences between rich and poor children in the U.S. than in Canada, at least for math scores and high school completion, could be that relative income positions are ‘stickier’ in the U.S. Plausibly, the ‘stickier’ are relative income positions, the more likely that starting life in a low- versus a high-income family will be associated with relatively low versus high attainments for the child since he or she spends a greater proportion of life in that income position. For children who were in the bottom quintile of the Canadian income distribution at age 0 to 7, Tables 10, 11 and 12 shows that 51.0 percent were again observed in the bottom quintile at age 10 to 17.Footnote 22 Of those children who were in the bottom quintile of the U.S. income distribution at age 0 to 7, 59.5 % were still in the bottom family income quintile at age 10 to 17. (If we use U.S. cut-off points for both countries, only 43.5 % of Canadian children who started life in the bottom quintile of the U.S. income distribution would still have incomes in the bottom quintile of the U.S. distribution at age 10 to 17.)

5 Conclusions

Using a cross-national comparative research strategy and longitudinal data, we study differences in educational outcomes for adolescents who were rich compared to poor as young children in Canada and the U.S. during the period 1994 to 2008. Following Smeeding et al. (2011), we argue that comparing two countries with different levels of inequality and different policies/institutions is a useful way to learn how inequality in outcomes for children emerges.

Although neither country has a particularly redistributive welfare state (e.g., by comparison with many European countries), income inequality is lower in Canada than the U.S. Of particular relevance to this study is the fact that Canada offers considerably more in the way of cash transfers to families with children, including cash payments for maternity/parental leave. It is also true that income positions are more ‘sticky’ for children in the U.S. than in Canada. For example, 59.5 % of children living in families in the bottom quintile when they are 0 to 7 are still in the bottom quintile 10 years later; in Canada, 51.0 % remain in the bottom quintile. Thus, any disadvantages/advantages associated with a low/high income position will persist over a longer period of time for children in the U.S. Finally, important institutions such as health care and education operate differently in the two countries, which may affect the degree to which income position is mediated.Footnote 23

Overall, our results are consistent with Corak et al. (2011) and Bradbury et al. (2012) in showing inequality in outcomes between children from advantaged and disadvantaged families, though our study focuses on somewhat older children and uses longitudinal data to takes account of family economic status from early childhood. In both countries, we find that children from affluent backgrounds fare better than children from disadvantaged backgrounds. In terms of cross-country comparisons, we find: 1) bigger gaps in math scores between rich and poor children in the U.S. than in Canada and; 2) a bigger rich-child/poor-child gap in the probability of completing high school in the U.S. It is important to emphasize that, for example, the rich/poor gap in mathematics performance is larger in the U.S. than in Canada both because poor children in the U.S. do worse than poor children in Canada and because rich children in the U.S. do better than rich children in Canada. Echoing Bradbury et al. (2012), we thus argue that it is important, when studying emerging inequality, to consider what is happening to affluent as well as disadvantaged children.

Interestingly, however, we find the gap between rich and poor children in educational aspirations to be larger in Canada despite finding that gaps in traditional educational outcomes such as math tests scores and dropping out of high school are larger in the U.S. To help understand what seems to be a paradox, it is useful to consider reported levels of aspirations in the two countries. An examination of Figs. 2 and 3 indicates that the main reason for the smaller gap in aspirations between rich and poor children in the U.S. is that lower-income children in the U.S. have particularly high aspirations. For example, 26 % of lower-income U.S. adolescents think they will complete two university degrees whereas only 17 % of Canadian adolescents hope they will do so. Since the rich/poor educational achievement gaps are in reality larger in the U.S. than Canada, it could be that lower-income children in the U.S. have less realistic expectations?

Although we recognize, as Corak (2006) points out, that policy interventions aimed at improving intergenerational mobility need to be weighed against their costs, we nonetheless hope that by identifying child outcomes where there are differences between Canada and the U.S. in the extent to which poor children lag rich children and by identifying differences in policies that might be relevant, our paper may help to guide further research seeking the most effective policies to at least somewhat ‘level the playing field.’

Notes

In terms of health status, this is both because poor children experience more negative shocks and because they are less able to buffer the consequences of shocks so that children can recover completely. Cunha and Heckman (2009) propose a model in which earlier development of child capacities (e.g., cognitive skills, non-cognitive skills and health) enhance the productivity of later investments; moreover, higher capacity in one dimension is argued to complement the capacity to grow in another (e.g., a healthy child can learn more easily).

A significant body of research documents differences in the extent of intergenerational mobility across countries (see, for example, Black and Devereux 2011 for an overview). Thus, we know that the end points differ, but know less about how/why less mobility takes place in the U.S. than in Canada or, especially, in Scandinavian countries, for example.

A number of studies emphasize that ‘permanent’ income has larger associations with child outcomes (e.g., Phipps and Lethbridge 2006)

Social assistance programmes are a provincial responsibility; the definition of being ‘in need’ thus varies across provinces.

Probit estimates of the probability of attending private school confirm that the rich-child/poor-child difference in private school attendance is statistically larger in the U.S. than in Canada. Bradbury et al. 2012 make the same point.

To the extent that any measures are not exactly comparable across countries, the research strategy of comparing rich/poor child outcome differences (rather than outcome levels) should be helpful.

Thus, we also avoid a potential cross-country comparability problem with ‘college’ which in Canada often means pursuing a two-year technical diploma at a ‘community college’ rather than a university degree.

All analyses have also been conducted using: i) the normalized math score, i.e., math score demeaned and divided by the standard deviation; ii) the quintile position of the child’s math score in own country. Results are extremely robust to these alternatives.

After-tax income is not available in all cycles of the NLSCY.

U.S. mothers report income in paper-and-pencil interviews (PAPI) before 1993 and in Computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) beginning in 1993 (Bureau of Labor Statistics (2008).

Canadian CPI is taken from CANSIM Table 3260002; US CPI is taken from CANSIM Table 3870007; PPP is taken from CANSIM Table 3800058.

All models have been estimated using both ordinary least squares and probit analyses. Conclusions are robust to choice of estimation technique.

We tried to use a ‘teen-age mother’ indicator but had insufficient numbers for Canada. We also estimated a quadratic in age (since children of older mothers may have additional health concerns, for example) but found the linear specification in mother age to be the best fit.

We also tried to include an indicator that the mother was attending school at the original survey date, but sample size did not allow us to use this indicator. Mother’s health status was similarly a problem with the Canadian data.

We are unable to control for ‘non-white’ status in the Canadian data given small sample size; we have run all U.S. models including this variable. Results are reported in Appendix 3.

Since the magnitude of estimated associations is not directly evident from probit coefficients, we report ‘average marginal effects.’ That is, using estimated coefficients and his/her own personal characteristics for all but the explanatory variable of interest, we calculate the percentage point change in the probability of, in this case, aspiring to high education,’ for each child as we change a particular explanatory variable (e.g., from ‘bottom quintile in period 1’ = 0 to ‘bottom quintile in period 1’ =1). The average marginal effect is then computed over all children.

Note that sample size falls due to non-response to some of the risk factor variables. In the interests of space, we do not report all estimated coefficients, but focus only on what happens to the estimated size and significance of ‘bottom quintile in first cycle’ after risk factors have been included.

U.S. results are unchanged when ‘non-white’ is included as a risk factor, though ‘non-white’ is associated with lower math scores (see Appendix 3).

Bailey and Dynarski (2011) find that the rich/poor gap in both high school completion and post-secondary achievement has increased over time in the U.S.

If we use U.S. quintile cut-points for Canada when selecting Canadian children whose family income 10 years ago would have put them in either the bottom or top of the U.S. income distribution, we lose some observations, in particular because fewer than 20 % of Canadian children had family incomes high enough to place them with the top 20 % of U.S. incomes. It is also true that 21.4 % of Canadian children had family equivalent incomes less than the cut point for the bottom U.S. quintile.

Again, although we use different samples for different adolescent/young adult outcomes, for the sake of brevity, we simply present results about ‘income stickiness’ for this one broad age group.

Again, please notice that our research focuses on the period between 1994 and 2008. To the extent that policies/institutions have changed since that time, these findings may be less relevant.

References

Almond, D., & Currie, J. (2011a). Human capital development before age five. Handbook of Labor Economics: Elsevier.

Almond, D., & Currie, J. (2011b). Killing me softly: the fetal origins hypothesis. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(3), 153–172.

Bailey, M. J., & Dynarski, S. M. (2011). Gains and gaps: Inequality in U.S. College entry and completion. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper 17633.

Black, S., & Devereux, P. J. (2011). Recent developments in intergenerational mobility. In Handbook of Labor Economics. 4:5, Ashenfelter, Orley and Card, David (ed). Elsevier.

Bradbury, B., Corak, M., Waldfogel, J., & Washbrook, E. (2012). Inequality in early childhood outcomes. In J. Ermisch, M. Jantti, & T. Smeeding (Eds.), From parents to children: The intergenerational transmission of advantage (pp. 87–119). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Brooks-Gunn, Jeanne & Duncan, Greg J. (1997). The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children. 7:2 Children and Poverty, pp. 55–71.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2006). Data user guide, National longitudinal survey of youth 1979 children & young adults.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2008). NLSY79 user’s guide: A guide to the 1979–2006 national longitudinal survey of youth data.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2009). NLSY79 child & young adult data users guide: A guide to the 1986–2006 child data 1994–2006 young adult data.

Burton, Peter. Phipps, Shelley & Zhang, Lihui. (2012). The Prince and the Pauper: Movement of children up and down the Canadian income distribution. http://myweb.dal.ca/phipps/Prince%20and%20Pauper%20April%202012.pdf.

Case, A., Lubotsky, D., & Paxson, C. (2002). Economic status and health in childhood: The origins of the gradient. American Economic Review, 92, 1308–1334.

Corak, M. (2006). Do poor children become poor adults? Lessons for public policy from a cross country comparison of generational earnings mobility. Research on Economic Inequality, 13, 143–188.

Corak, Miles. Curtis, Lori & Phipps, Shelley. (2011). Economic mobility, Family background, and the well-being of children in the United Sates and Canada, Chapter 3 in Persistence, Privilege and Parenting: The Comparative Study of Intergenerational Mobility. Robert Erikson, Markus Jantti, and Timothy Smeeding (Editors), Russell Sage Foundation, pp. 73–108.

Cunha, F., & Heckman, J. (2009). The economics and psychology of inequality and human development. Journal of the European Economics Association, 7(2–3), 320–364.

Currie, J. (2011). Inequality at birth: some causes and consequences. American Economic Review, 101(3), 1–22.

Currie, J. (2009). Health, wealthy, and wise: socioeconomic status, poor health in childhood, and human capital development. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(1), 87–122.

Currie, J., & Stabile, M. (2003). Socioeconomic status and child health: why is the relationship stronger for older children? American Economic Review, 93, 1813–1823.

Danziger, S. K., & Danziger, S. (2010). Child poverty and antipoverty policies in the United States: Lessons from research and cross-national policies. In S. B. Kamerman, S. Phipps, & A. Ben-Arieh (Eds.), From child welfare to child well-being: An international perspective on knowledge in the service of policy making. New York: Springer Press, pp. 255–274.

Ding, W., & Lehrer, S. F. (2010). Estimating Treatment Effects from Contaminated Multiperiod Education Experiments: The Dynamic Impacts of Class Size Reductions. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(1), 31–42.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fortin, N., Oreopoulos, P., & Phipps, S. (2012). Leaving boys behind: Gender disparities in high academic achievement. http://faculty.arts.ubc.ca/nfortin/LeavingBoysBehind.pdf.

Frenette, M. (2005). Is post-secondary access more equitable in Canada or the United States? Statistics Canada. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series. Catalogue no. 11F0019MIE – No. 244.

Human Resources and Social Development Canada. (2010). National Child Benefit Progress Report, 2007. Available at: http://www.nationalchildbenefit.ca/eng/07/sp_119_11_07_eng.pdf (accessed October, 22, 2012)

Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Key Figures, http://www.lisproject.org/key-figures/key-figures.htm ({October 4, 2012})

Phipps, S., & Lethbridge, L. (2006). Income and the outcomes of children. Statistics Canada. Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series. Catalogue No. 11F0019MIE – No. 281.

Picot, G., Zyblock, M., & Pyper, W. (1999) Why do children move into and out of low income? Changing labour market conditions or marriage or divorce? Statistics Canada, Analytical Studies Branch Working Paper.

Smeeding, T. M., Erikson, R., & Jantii, M. (Eds.). (2011). Persistence, privilege, and parenting: The comparative study of intergenerational mobility. New York: Russell Sage.

Statistics Canada. (2005). Microdata user guide, national longitudinal survey of children and youth, cycle 6.

Statistics Canada. (2008). Microdata user guide, national longitudinal survey of children and youth, cycle 8. Available at: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb-bmdi/document/4450_D4_T9_V8-eng.pdf

Waldfogel, J., & Washbrook, E. (2011). Income-related gaps in school readiness in the United States and the United Kingdom. Chapter 6. In T. M. Smeeding, R. Erikson, & M. Jantii (Eds.), Persistence, privilege, and parenting: The comparative study of intergenerational mobility (pp. 175–207). New York: Russell Sage, pp. 175–208.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Inverse probability weighted m-estimators for sample selection, attrition, and stratification. Portuguese Economic Journal, 1(2), 117–139.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2001). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Table 13 shows the detailed process of arriving at our baseline regression (as in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7) samples. Starting from the samples of children in appropriate age ranges 10 years ago, we follow five steps to construct our baseline regression samples. First, we use the lowest common denominator approach to make the samples from both countries comparable to each other. Second, we drop those observations that were in the survey in the first but not in the sixth cycle. Third, we drop those who do not have valid responses to our dependent variables. Fourth, those without valid responses to our independent variables are dropped. Finally, we keep only those in incomes quintiles 1 or 5 given our primary interest in the top–bottom disparity. As seen in Table 13, in the Canadian case, most observations are dropped for the purpose of making the samples comparable to the US. Attrition is a large cause for loss of observations for both countries. In addition, non-responses to the dependent variables and to the independent variables lead to some further reductions in sample sizes. The last step drops about 60 % of the sample, which is as expected.

Given the significant number of observations dropped due to attrition and non-responses, a natural concern is that this may bias the statistical results obtained from those children that remain in the sample if such drops are not at random (Wooldridge 2001). That is, the elimination of observations depends on either observables or un-observables.

In our baseline regressions, we use the longitudinal weights from the sixth cycle supplied by Statistics Canada in the NLSCY masterfiles, which are intended to preserve the representativeness of the original longitudinal children, given sample attrition (Statistics Canada 2005).

To further confirm that these baseline regression results are robust to the sample reductions, we use the inverse probability weighted (IPW) M-estimator approach suggested by Wooldridge (2002) and illustrated by Ding and Lehrer (2010). The IPW approach produces consistent estimators provided that attrition is based on observables rather than un-observables, that is, attrition probability is independent of the dependent variable. Following this approach, we first estimate the probability of a child staying in the sample using probit regressions, where staying in the sample means that the child is present in both the first and the last cycle and has valid responses to the dependent variables. The independent variables include those used in our baseline regressions, with the bottom income quintile dummy replaced by the log of household equivalent income to retain more information on family economic resources. To increase the precision of our estimated probabilities of staying in the sample, we also include four dummy variables indicating whether the child is present in the second, third, fourth, and fifth cycle, respectively, and we make use of children in all income quintiles, not just those in the bottom and top quintiles 10 years ago. The second step entails using the inverse of the estimated probabilities of staying in the sample obtained from the first step to reweight our baseline regressions. The IPW probit regression results are presented in Tables 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19. As explained in Wooldridge (2002), here the standard errors are overly large rendering more conservative inferences, i.e., we are less likely to reject the null hypotheses. A comparison between results in Appendix Tables 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19 and those in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 reveal no dramatic differences in the estimates, suggesting non-random attrition bias, at least in terms of observables, is not a significant concern.

Appendix 2. Details of Sample Construction for Outcome Variables

1.1 Equivalent Household Income

Canadian sample: 10–17 years old in 2004 (0–7 years old in 1994)

U.S. sample: a pooled sample of four cohorts: i) 16–17 years old in 200 (6–7 years old in 1990); ii) 16–17 years old in 2002 (6–7 years old in 1992); iii) 10–17 years old in 2004 (0–7 years old in 1994); and, iv) 10–11 years old in 2006 (0–1 years old in 1996).

1.2 Educational Aspirations

Canadian sample: a pooled sample of two cohorts: i) 12–15 years olds in 2004 (2–5 years old in 1994); and, ii) 12–13 years old in 2006 (2–3 years old in 1996)

U.S. sample: a pooled sample of four cohorts: i) 14–15 years old in 2000 (4–5 years old in 1990); ii) 14–15 years old in 2002 (4–5 years old in 1992); iii) 12–15 years old in 2004 (2–5 years old in 1994); and, iv) 12–13 years old in 2006 (2–3 years old in 1996).

1.3 Math Score

Canadian sample: a pooled sample of two cohorts: i) 12–14 years olds in 2004 (2–4 years old in 1994); and, ii) 12–13 years old in 2006 (2–3 years old in 1996)

U.S. sample: a pooled sample of four cohorts: i) 13–14 years old in 2000 (3–4 years old in 1990); ii) 13–14 years old in 2002 (3–4 years old in 1992); iii) 12–14 years old in 2004 (2–4 years old in 1994); and, iv) 12–13 years old in 2006 (2–3 years old in 1996).

1.4 Education Attainment

Canadian sample: a pooled sample of two cohorts: i) 20–21 years old in 2004 (10–11 years old in 1994); and, ii) 19–21 years old in 2006 (9–11 years old in 1996).

U.S. sample: a pooled sample of two cohorts: i) 20–21 years old in 2004 (10–11 years old in 1994); and, ii) 19–21 years old in 2006 (9–11 years old in 1996).

Appendix 3

Table 20

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burton, P., Phipps, S. & Zhang, L. From Parent to Child: Emerging Inequality in Outcomes for Children in Canada and the U.S.. Child Ind Res 6, 363–400 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-012-9175-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-012-9175-1