Abstract

In our continuously changing society, a need for updating one’s skills and knowledge puts pressure on safeguarding the labour market position of low-qualified employees. However, prior research and official statistics show that employees with a lower level of education tend to participate less in training than highly-educated individuals. This limited participation is associated with employers offering fewer opportunities to low-qualified employees, but also with the fact that low-qualified employees themselves might be less willing to participate. In other words, their learning intentions are assumed to be weaker and more restricted than the learning intentions of highly-educated employees. The article reports on a quantitative survey research on the learning intentions of 406 low-qualified employees. The results showed that employees who participated in formal job-related learning activities during the last 5 years had a stronger learning intention than those who did not. Next, the results of the stepwise regression showed that self-directedness, financial benefits, self-efficacy, and autonomy were significant positive predictors of the learning intentions of low-qualified employees. Also, the limited number of possibilities or opportunities to learn was not significant. The results indicated that a learning intention can lead towards the participation in learning activities, but participation is not merely initiated by offering opportunities for learning. Organisational aspects such as job autonomy and financial benefits can stimulate the learning intention of an employee. Finally, regarding the socio-demographic variables, only limited differences were found. In short, employees with no educational qualifications and a full-time contract had the lowest intention to learn.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A policy of lifelong learning is a central lever in creating a competitive and knowledge-based economy (Boeren et al. 2010). It also plays an important role in governing the labour market in general, and increasing the employment rate in particular (Rainbird 2000). In our continuously changing society, a need for updating one’s skills and knowledge puts pressure on the labour market position of low-qualified employees (De Grip and Zwick 2004). Due to increasing role of computers and technology, the demand for traditional manual low-qualified workers has declined, making the position of low-qualified employees even more vulnerable (Gvaramadze 2010). Participation in learning activities is often considered as a key factor to economic competitiveness and individual well-being. Through education and training, low-qualified employees could improve their vulnerable position on the labour market (Prince 2008). The Employment Guidelines of the European Commission, derived from the Lisbon agenda of the European Council, are aiming at improving the access to training, particularly for low-qualified workers (De Grip and Zwick 2004; European Commission 2003). It is stated that if low-qualified workers receive additional training, they can also benefit from the changes on the labour market where there is demand for skills. However, prior research has shown that the level of education, that is formal qualification, is an important predictor of participation in vocational training (e.g. Greenhalgh and Mavrotas 1994; Tharenou 1997), and that employees with a higher level of education tend to participate (much) more in training (Greenhalgh and Mavrotas 1994; Illeris 2006; Rainbird 2000; Tharenou 1997)—up to seven times more—than low-qualified individuals (Boeren et al. 2010). Burdett and Smith (2002) call it the “low skill trap”: a lower level of initial education goes hand in hand with a less favourable starting position in the labour market, which leads to the fact that these individuals often fill lower positions in organisations with fewer career perspectives and development possibilities. From a short-term management point of view, these lower functions do not require additional training and the return on investment of the training is considered low (Burdett and Smith 2002). In particular, profit seeking organisations are often reluctant to invest in the training of low-qualified employees (Asplund and Salverda 2004). However, the labour market will also be confronted with a growing shortage of employees, making the retention of employees vital for the existence of successful organisations. Former research has shown that when employees feel that they can develop themselves within their organisation that they are less inclined to leave the organisation (Govaerts et al. 2011; Kyndt et al. 2009a). In order for an organisation to be able to keep on benefiting from all skills of their employees, it will become increasingly important to adopt a long-term perspective when it comes to the training and development of low-qualified employees (Renkema and van der Kamp 2006).

In addition to the fact that low-qualified employees might not receive as many opportunities to participate in education and training, such employees are also less likely and less eager to participate in training (Illeris 2006). Illeris points out that their educational career is often an accumulation of negative experiences, which in turn can lead to a lack of confidence regarding “learning”, and discourages participation in further training. It is assumed that the “intention to learn”, i.e. the readiness of low-qualified employees to participate in training which is a necessary prerequisite on the way to participation, could be low due to their negative experiences with regard to prior education. Former research has shown that learning intention and participation in learning activities are closely related. More specifically Raemdonck (2006) found that employees who have already participated in training have a stronger learning intention.

Low-Qualified Employees

Low-qualified employees can be conceptualised from two different perspectives: the labour market and the educational perspective. The labour market perspective more commonly uses the term low-skilled employees and focuses on the position of employees on the labour market and market segmentation. The educational perspective stresses the role of (the initial) education and training (Gvaramadze 2010). In this article, an educational perspective is taken up defining low-qualified employees as individuals who are currently employed and do not possess a starters qualification for higher education. However, an influence of the economic perspective exists; low-qualified employees are confronted on the labour market with an insufficient academic background and low levels of training outside of their initial schooling. The decline of the need for manual workers because of technological innovations and the rise of newly required skills and competences as a consequence, place low-qualified employees in a vulnerable and unstable position threatened by unemployment (Gvaramadze 2010; Torka et al. 2010). The participation in learning activities could improve the position of the low-qualified employee on the labour market. However, existing literature is consistent in its finding that a positive relationship exists between participation in learning activities and educational qualifications, meaning that the group of low-qualified employees who could potentially benefit the most from participating in learning activities, actually participates the least. The higher the initial level of education, the more likely it is that an employee will participate in learning (Greenhalgh and Mavrotas 1994; Gvaramadze 2010; Shields 1998; Tharenou 1997). In addition, the distribution of opportunities to participate in learning activities is differentiated according to educational level. High-skilled employees participate more in learning activities and are offered more opportunities.

The research on learning intentions is more limited and less focused when it comes to the learning intentions of low-qualified employees (Hazelzet et al. 2009; Raemdonck 2006). In a sample in which employees of all educational levels are represented, one would expect those with a higher educational level would score higher, not only with respect to participation rates, but also in terms of their learning intentions in comparison to low-qualified employees. Furthermore, Illeris (2006) states that low-qualified employees do however recognise the importance of formal learning but wish it were not necessary because of experiences of failing at school.

Learning Intentions

The theory of reasoned action (Ajzen 1991; Fishbein and Ajzen 1975) provides an interesting theoretical background for studying the learning intentions of (low-qualified) employees. An individual’s learning intention is conceptualised as the proximal determinant of participation in learning activities. Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) consider the intention to engage in a specific behaviour as a strong indicator for actual behaviour. Also Maurer et al. (2003) for example found that the intention for participation in learning activities was a robust predictor of actual participation. They state that getting employees to commit to being involved in learning activities is a first valuable step towards actual participation (Maurer et al. 2003).

According to the theory of reasoned action the learning intention is determined by the attitudes of the learner towards the behaviour at hand and the subjective social norm. The attitude of the learner concerns the expectations with regard to the results of the behaviour, and the estimation of the balance between positive and negative consequences of participating in a learning activity (Baert et al. 2006a). The subjective social norm is derived from two elements: the perception of the beliefs of significant others and the tendency the individual has to conform. Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) emphasise that the perception of the social norm is more important than the actual “objective” behaviour of the significant others.

This theory integrates attitudes and subjective norms into a rational decision-making process. Nevertheless, it does not consider the influence of several contextual variables. However, other conceptual models do focus on such contextual influences. In Rubenson’s (1977) “expectancy-valence model”, for example, a lot of attention is given to both personal and contextual factors that motivate and prompt individuals to participate in learning activities. Rainbird (2000) also stresses the importance of both individual characteristics, and factors that are extrinsic to the individual concerning their structural position in the organisation. Baert et al. (2006a) also recognise in their theoretical model that the factors that influence this decision-making process are not only related to the characteristics of the learner, but also to the characteristics of the learning activity and the social context.

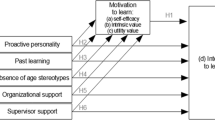

Baert et al. (2006a) place the development of a learning intention central within the decision-making process of the potential learner. This decision-making process is seen as the increasing articulation of an educational need (Baert 1998). Figure 1 gives a schematic overview.

Decision-making process of the potential learner (Baert et al. 2006a)

This process starts out with a need, an awareness that something is lacking, or that a discrepancy exists between someone’s current and desired situation. This need can involve several aspects such as money, time, resources, materials or health conditions. When educational aspects are recognised, an educational need will be more or less articulated. For example, the birth of a third child leads to the awareness that someone’s current house will become too small as the children grow up. This can lead to the fact that this person wants to earn more money in order to buy or rent a bigger house by seeking promotion. While realising this in order to obtain that promotion, he might have to expand his knowledge and skills.

According to the theory of reasoned action (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980; Fishbein and Ajzen 1975), a learner who articulates an educational need should develop the intention to participate in learning. The development of this learning intention can result from the expression of a certain desire to learn, which is conceptualised by Confessore and Park (2004) as a basal component of autonomy. This assumes that an individual is intrinsically or extrinsically motivated to learn. The social-psychological model of Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) emphasises the intentional character of the decision maker (Silva et al. 1998), and states that these intentions steer the participative behaviour of a person, and leads to the formulation of an educational demand (Baert et al. 2006a). In this stage, the learner takes action to meet his needs. For example, the learner searches for a training programme or a self-learning activity that can help him fulfil his needs. If he finds one, this does not automatically mean that the found solution is also the best or the most appropriate solution. It can happen, for example, that the aim of the programme fits with his interests, but that the duration, the didactics, the place or the price of the programme presents obstacles preventing effective participation. Only the final step in the decision making process—after evaluating all relevant features—is the actual educational participation.

In summary, a learning intention can be defined as a readiness or even a plan to undertake a concrete action in order to neutralise the experienced discrepancy, and to reach a desired situation by means of training and education. In this research the focus was on learning intention regarding formal job-related learning activities. These learning activities can occur both on- and off-the-job, and involve learning actions that are not mandatory. The latter means that participation in these learning activities does not lead to a starter qualification for higher education.

Factors Influencing the Learning Intention

Several authors have emphasised the importance of both personal and contextual influences on the learning intention and participation of individuals (Rainbird 2000; Rubenson 1977). However, former research on these influences is limited and has been focusing on several variables leading to the fact that a sound theoretical and empirically validated model does not yet exist. In this section we will discuss the literature and previous research on the factors influencing the learning intention and actual participation of employees, following the categories of Baert et al. (2006a). Baert et al. (2006a) divide these factors into three categories: the perception about the characteristics of the learner (micro-level), the characteristics of the learning activity (meso-level), and the broader social context and its actors (macro-level). These factors determine the attitude of the individual, and as a consequence, influence the development of the learning intention of that individual.

Characteristics of the Learner (Micro-Level)

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

In previous research, various socio-demographic characteristics have been linked with learning intentions and participation in learning activities. In terms of gender Hazelzet et al. (2009) did not find a difference in learning intention between males and females. Regarding age, research on participation has shown that participation in learning activities declines with age (Boeren et al. 2010). Renkema and van der Kamp (2006) found that age and learning intention were mutually dependent in a sample of employees working in technical installation companies. Older employees had more restricted learning intentions than their younger colleagues. More recent research also confirmed the negative relationship between age and the intention to engage in developmental activities (Renkema et al. 2009). As employees get older they are less inclined to take up learning activities of any kind (Maurer et al. 2003). However, in a sample of employees in the elderly care sector, this relationship was not confirmed (Renkema and van der Kamp 2006). In addition, the research by Hazelzet et al. (2009) did not yield a significant relationship. Closely related to age is seniority or tenure within an organisation. Research found that seniority influences the intention to engage in development activities; however Noe and Wilk (1993) argue that this influence is likely to be related to the opportunities these employees have to participate. Renkema et al. (2009) confirmed the negative relation between tenure and intention to learn.

Psychological Characteristics

Previous empirical research has investigated the relation of several psychological characteristics with the learning intentions of employees. Raemdonck (2006) investigated the self-directedness in learning and career processes in a group of low-qualified employees. Self-directedness is needed to cope with finding and keeping a position in the labour market. Self-directedness in career processes concerns influencing the course of one’s own career, while self-directedness in learning focuses on job-related learning activities that an employee intentionally undertakes. Raemdonck (2006) found that the self-directedness in career processes correlate positively with the intention to participate in future learning activities. The relation between self-directedness in learning and learning intention was even stronger. Hazelzet et al. (2009) investigated factors that influenced the intention to participate in training of at least 1 day a week during a period of a minimum of 6 months. In line with the research by Raemdonck (2006), they found that career planning and orientation towards career opportunities are significant predictors of the intention to participate in training.

Prior research has also discovered a positive relationship between self-efficacy and the intention to learn for employees of all educational levels (Maurer and Tarulli 1994; Renkema et al. 2009) and specifically in a sample of low-qualified employees (Hazelzet et al. 2009; Renkema 2006). Self-efficacy is the expectation an individual has concerning his own capacities to perform successfully in a certain situation (Bandura 1997). In the research by Hazelzet et al. (2009), the concept of self-efficacy is defined as the belief that employees have about their ability to manage and complete the learning activity successfully.

Concerning personality, results showed that the more extravert a person is, the more restricted his intention to participate is (Hazelzet et al. 2009).

The research of Colquitt et al. (2000) found that both job satisfaction and organisational commitment influence the intention to engage in development activities positively. Renkema et al. (2009) also found a strong positive relationship between job satisfaction and learning intention. Finally, the last variable in this category that was found to correlate positively with learning intentions was employability (Raemdonck 2006). Kirschner and Thijssen (2005, p. 72) defined employability as “the behavioural tendency that focuses on acquiring, maintaining, and using qualifications aimed at participating in and coping with the changing labour market throughout all career stages”.

Characteristics Regarding the Living Situation

Another category of factors at the micro level refers to characteristics of the living situation which appear to be important when considering the benefits and disadvantages of participating in a learning activity (Baert et al. 2006a). For example, Baert et al. (2009) propose that the expected financial benefits of participating in learning would positively influence the learning intention of the employee. Research has shown that the work-life balance is very important for the well-being of employees (Gropel and Kuhl 2009), for the retention of employees (Kyndt et al. 2009a) and for their participation in learning activities (Brown 2005). In their research, Hazelzet et al. (2009) found that the pressure coming from relatives to participate in training has a positive relationship with the learning intentions of employees in the profit sector. Another influential aspect of the living situation might be the fact that the employee works full-time or part-time, and that his appointment is either permanent or temporary. In other words, the type of contract might have an influence. Keijzer et al. (2009) found that the risk of losing one’s job is positively related to the learning intention of an employee. Based on this finding, we can expect that employees with a permanent appointment within an organisation might have a weaker learning intention than their colleagues with a temporary contract.

Characteristics Regarding Learning, Education and Training

In this research the difference between learning on the one hand, and education and training on the other, is that learning is the process in which competences are acquired, while education and training refer to the offer that allows learning to take place.

When considering participation, a learner makes use of the experience, the knowledge and the ideas about learning and education he collected during his lifetime. Besides the above discussed initial level of education, former participation in learning activities also influences the learning intention of an individual. Research has shown that participation in previous learning activities yields a positive correlation with learning intention (Raemdonck 2006; Renkema 2006). Moreover, the more positively a course was evaluated, the more inclined participants were to take up courses in the future (Renkema 2006). The attitude of employees towards learning activities has been shown to be strong predictors of their learning intention (Maurer et al. 2003; Noe and Wilk 1993; Renkema et al. 2009). Attitude towards development comprises the interest shown in development, the desire for the outcome and the importance of development for the employee (Renkema et al. 2009).

Characteristics of the Learning Activity (Meso-Level)

Besides the individual characteristics, factors at the level of the learning activity also play a role in the decision making process of the individual. The research by Boeren (2011) showed that adult classroom environment variables, more specifically support, autonomy and clear organisation, contribute positively to the sustained participation of individuals. Former research on the participation in learning activities has also shown that financial costs (course fees, didactic materials, etc.) constitute a barrier to participation in learning activities (De Meester et al. 2001). Finally, the reputation of the training, trainer or training institute may be taken into account in any decision to participate in formal learning activities: a positive reputation can lead to increased participation.

Characteristics of the Social Context and its Actors (Macro-Level)

The entire decision making process of the individual is embedded in a broader social context in which several actors have various roles. Therefore, the social context can also influence the attitude towards educational participation and the opportunities to participate in learning activities (Baert et al. 2006a). In their theory Fishbein and Azjen (1975) also refer to the influence of social norms and relevant others on the learning intention of individuals. The factors investigated that belong to the social context in relation to the learning intentions of employees were mainly found at the level of the organisation in which the employee is active. Raemdonck (2006) found that task variety or the extent to which a job is diversified in terms of the number of tasks that have to be done, correlated positively with the intention to learn. The potential to grow within a job or an organisation is also related positively to employees’ intentions to learn (Raemdonck 2006). In the profit sector, the support within the working environment was positively correlated with the learning intentions of low-qualified employees (Colquitt et al. 2000; Eisenberger et al. 2002; Hazelzet et al. 2009; Maurer and Tarulli 1994; Noe et al. 1990; Renkema 2006). Tharenou (1997) confirmed the hypothesis that participation in training and developmental activities is linked to the perception of how supportive an organisation is towards learning and development. Doornbos (2004) sees autonomy in performing one’s job as a characteristic of the organisation that can influence job-related learning. Autonomy relates to the feeling of being free to act, having an own choice and the idea that behaviour is set voluntarily (Ryan and Deci 2000). High autonomy in the workplace reflects the freedom to choose how to do one’s job or how to solve problems. The more an employee understands his environment as being supportive of his autonomy, the greater will be the intention of that employee to learn (Doornbos 2004). In addition, Renkema and van der Kamp (2006) argue that “…a learning intention might relate to differences between a short-term imperative and a long-term perspective on the corporate development of the management of the organisation” (Renkema and van der Kamp 2006, p. 253). Offering employees opportunities to gain positive learning experiences, by applying a long-term perspective on corporate development, has a positive influence on the affective attitude towards learning activities and by consequence on the learning intention of employees (Renkema and van der Kamp 2006).

Present Study

The present study focuses on the learning intentions of low-qualified employees. In this research low-qualified employees are operationalised as employees who do not have a starters-qualification for higher education. This means that they do not possess a secondary education diploma or equivalent. It needs to be noted that this operationalisation is characteristic for post-industrial countries where knowledge and consequently education play an important role in sustaining the development and living standards of and within that country. These low-qualified employees are often confronted with both personal and contextual barriers when it comes to participating in learning. On the one hand, employers offer them relatively few possibilities to participate in training, but on the other hand, low-qualified employees are much less inclined to take up any learning opportunities that exist because of prior negative experiences of learning. In addition, their position in the labour market is vulnerable, since lifelong learning, and as a consequence, flexible knowledge and skills, have become very important in terms of keeping up in our continuously changing society (Burdett and Smith 2002; De Grip and Zwick 2004; Illeris 2006). This study agrees with the statement that low-qualified workers can also cope with changes in the labour market and its demands for skills if they participate in additional and continuous training (De Grip and Zwick 2004). Therefore it is important to investigate, more extensively then in former research, the learning intentions of low-qualified employees, as the preceding phase of actual participation, so that we can understand how these learning intentions are constituted, and what influences them. Hence, in this study the focus is on factors that influence the learning intentions of low-skilled employees. The specific research questions in this study are:

-

Are the learning intentions of employees related to previous participation in formal job-related learning activities? Are the learning intentions of employees who participated in previous formal job-related learning activities different from those who did not participate?

-

Do the learning intentions of employees differ between different groups of employees in terms of gender, children, initial educational level & contract type? Is there a relationship between the employees’ age and seniority within the organisation, and their learning intention?

-

What is the relationship between a learning intention and the individual characteristics of self-efficacy and self-directedness in the career process?

-

What is the relationship between a learning intention and perceptions of job-related characteristics such as support from the executive, autonomy, and financial benefits?

Method

Participants

The sample in this study consisted of 406 low skilled employees. In total 177 males (44%) and 229 females (56%) completed the questionnaire. Data were collected in 19 different organisations from different lines of work. These organisations were, for example, cleaning companies, messenger services, technical services for cities, (car) assembly plants, child care services and companies from the food industry. Participants were invited to participate in this study based on the definition of low-qualified employees as stated above. Within this low-skilled group, 18% did not have a diploma or certificate of any kind. For 13.3%, the highest obtained level of education was elementary school and 31.3% had obtained a lower secondary education diploma (3 years of secondary school). Some 29.3% had finished secondary education within a vocational track which awarded them a vocational certificate that was not equal to a diploma of secondary education. This vocational certificate does not grant access to higher education. 4.4% obtained a degree in special needs education. The remaining 3.7% indicated that they had obtained “another” educational level such as an apprenticeship in construction. Finally, the majority of the respondents were employed full-time (58.9%), 28.6% worked part-time, 4.9% had a temporary contract, and 7.6% indicated that they had “another” type of contract.

Instruments

The written questionnaire started out by collecting information with regard to the participants in terms of their gender, age, seniority, number of children, organisation, type of contract, initial educational level and previous participation in formal job-related learning activities. Formal job-related learning activities could take place on- or off-the-job, and during or after working hours. Examples of such learning activities were training, study groups, introductory activities, computerised self-study, etc. The second part of the questionnaire was constructed using scales that have been used in related former research studies. All variables were measured by the perceptions of the participants, since Fishbein and Azjen (1975) state that a person’s behaviour is foremost guided by the perception of the environment rather than the objective environment. The variable learning intention was measured using five items derived from the research by Hazelzet et al. (2009). All items measuring learning intention can be found in Appendix 1. The variable self-directedness in the career process was measured using the scale constructed by Raemdonck (2006) that consisted of eight items. The eight items focusing on financial benefits were derived from the research by Biessen and de Gilder (1993) and Van Veldhoven et al. (1997). The six items measuring the perceived support and opportunities from the employer were based on the research of Baert et al. (2009). Perceived job autonomy was measured using ten items derived from Baert et al (2006b). Finally, self-efficacy was measured using three items (Keijzer et al. 2009). In total 29 items were retained after the factor analysis (see Appendix 2).

To collect our data, printed questionnaires were distributed within the organisations by a contact person of the human resource department within the organisation. All employees completed the questionnaires on a voluntary basis during their working hours or short breaks at work.

Analyses

The analysis started with the calculation of the descriptive statistics to describe the sample. Following, an exploratory factor analysis was performed on the scale of the dependent variable learning intention. The extraction was performed based on the maximum likelihood method. In order to perform this analysis, it was necessary to check if the data was suitable for factor analysis. This statistical control was based on three criteria: the determinant of the correlation matrix, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The determinant equals .211, which is relatively high, but in combination with a KMO measure of .827, and a significance of lower than .001 on the Bartlett test, it can be concluded that these data were suitable for factor analysis. In order to answer the first research question concerning the relationship between learning intention and previous participation in formal job-related learning activities, a correlation was calculated, followed by an ANOVA in order to compare the group that participated in the last 5 years to those who had not. A second set of ANOVA analyses were performed to compare groups with different demographic characteristics regarding their learning intention. In order to answer the final two research questions, a second exploratory factor analysis was performed on the scales measuring the independent variables chosen in the research questions. Although separate, existing scales were selected, we performed an exploratory factor analysis to check the unidimensional structure of the scales, since it is the first time that data with regard to the selected variables were collected together and from this type of population. For these data the determinant amounted to .002, the KMO measure equalled .785, and the significance of the Bartlett test was lower than .001. It can be concluded that these data were also suitable for factor analysis. Subsequently, all factors were introduced in a stepwise linear regression to determine which variables significantly predicted the learning intention of low-qualified employees. All the ANOVA and regression analyses were conducted with the factor scores (method regression).

Results

As mentioned before, the analysis aimed at answering our research questions was started with an exploratory factor analysis for the dependent variable learning intention. The analysis resulted, as expected, in a one factor solution that explains 47% of the variance. The alpha reliability coefficient (α) amounted to .814. The factor loadings of the items can be found in Appendix 1.

Our first research question investigates if a low-qualified employee’s learning intention is related to participation in previous formal job-related learning activities. To answer this question, the learning intentions of the group that participated in a formal job-related learning activity during the past 5 years were compared with those who had not. The results showed that the learning intention of the group that participated (n = 159) was significantly higher than that of those who did not participate (n = 246) (F(1,396) = 10.648, p < .01, η² = .03). The groups are not equal in size, but the assumption of homogeneity of variances was not violated (Levene’s F = 2.902, p = .089).

Secondly, different socio-demographic groups were compared regarding their learning intentions. No differences were found between males and females, or between employees with or without children. A two-way ANOVA with regard to gender and number of children also did not yield any significant differences. For type of contract, significant differences in learning intentions were found (F(3,390) = 4.154, p < .05, η² = .03). Bonferroni post-hoc tests showed that employees with a permanent appointment (full-time and part-time contracts) have less expansive learning intentions than employees with “another” type of contract such as freelance, independent worker and starter jobs.

Another ANOVA analysis was performed to investigate if differences in different types of diplomas regarding the learning intention existed even within this low-qualified sample. Bonferroni post-hoc tests of the ANOVA analysis only showed significant differences between employees with no diploma at all (n = 73) and employees with a diploma in special education (n = 18). The learning intention of employees with no diploma was the lowest (F(5,392) = 2.393, p < .05, η² = .03). The assumption of homogeneity of variances was not violated (Levene’s F = 2.182, p = .055). The final socio-demographic characteristic that was investigated was the seniority of the employees within organisations. The results showed that seniority and learning intention were significantly negatively correlated (r = −.11, p < .05). Employees with higher levels of seniority within the organisation had a weaker learning intention. Although age and seniority are significantly correlated (r = .426, p < .001), no significant relationship was found between the age of the employee and his learning intention.

To answer the final two research questions, a second exploratory factor analysis on the items measuring the independent variables was performed. The final model yielded a six factor solution that explained 41.91% of the variance. The six factors measured; self-directedness in the career processes of the employee, financial benefits, self-efficacy, perceived job autonomy, perceived limited number of chances and support for participation, and finally perceived stimulation from the employer. The reliability of this last factor is however too low (α = .56). Therefore this variable will not be taken up in the further analyses. All information regarding the items, explained variance and reliability of the factors can be found in Appendix 2.

Table 1 shows the correlations between learning intention and the independent variables. The learning intentions of the employee are positively correlated with self-directedness in career processes, self-efficacy, and financial benefits. It is also interesting to see that self-efficacy correlates positively with self-directedness in the career process and the perception of having too little opportunities to participate in learning activities.

The results of the stepwise linear regression show that learning intentions are significantly positively predicted by self-directedness in career processes, self-efficacy, financial benefits, and perceived job autonomy (see Tables 2 and 3). Perceived limited number of chances and support for participation was excluded from the final model (β In= −.075, t = −1.628, p = .104).

Discussion and Conclusion

This study focused on the learning intentions of low-qualified employees. The concept of learning intention was defined as a readiness or even a plan to undertake a concrete (learning) action to neutralise the experienced discrepancy, or to reach a desired situation by means of training and education. The majority of former research studies have focused on the actual participation of low-qualified employees, and conclude that the participation rate is low, and with respect to the changing labour market requirements one might even say too low. Actual participation rates of low-skilled employees can be potentially influenced by the fact that employers offer lesser opportunities for participation to low-qualified employees (Boeren et al. 2010; Burdett and Smith 2002). Focusing on the learning intention, rather than actual participation, allows us to deal with a broader scope and with concerns about sustainable employability. In addition, it provides an opportunity to investigate why low-qualified employees rarely participate in lifelong learning activities detached from the fact that employers offer them fewer opportunities. The research of Maurer et al. (2003) showed that learning intention is a robust predictor for actual participation. The learning intentions of employees are a first important step towards actual participation.

In conclusion, this research has shown that learning intentions are related to participation in (previous) learning activities, while employees’ perceptions of the opportunities offered by the employer do not predict their learning intention. These results indicate that a learning intention can lead towards participation in formal job-related learning activities, but that it is not initiated merely by the offer of learning opportunities. Organisational aspects such as perceived job autonomy and financial benefits can stimulate the learning intention of an employee. When focusing on individual characteristics, we found that self-directedness in career processes and self-efficacy are positive predictors of the learning intentions of low-qualified employees. It is also interesting to see that an employee characterised by a high degree of self-efficacy, is more self-directed in his career, has a stronger learning intention, and has a higher perception of not having sufficient chances to participate in learning activities.

Future research can investigate the causality of the relationship between self-efficacy, self-directedness and a learning intention. It can be questioned whether more self-efficacy, or belief in one’s own abilities, leads to a more active and reflective approach concerning one’s career processes, and whether this does in turn initiate and stimulate the learning intention of the employee. One would expect it does since in almost all learning situations self-efficacy has a clear influence as shown by Van Dinther et al. (2011). Regarding the socio-demographic variables, only limited differences were noticed. In summary, employees with no diploma and a full-time contract had the lowest intention to learn. Employees with no diploma probably have had a lot of negative experiences with education, and are therefore not likely to participate in any learning activity again (Illeris 2006). Even within a low-qualified sample as in this study, the influence of the initial educational level remains visible, and in line with former research that shows that intention to learn and participation in learning activities are positively related to the level of education (Greenhalgh and Mavrotas 1994; Tharenou 1997). Employees with a full-time contract on the other hand, probably do not feel the need to learn, since they do not think they are at risk of losing their job. Keijzer et al. (2009) found that the real or expected risk of losing one’s job can stimulate the learning intention of an employee.

Although our sample, questionnaire and statistical operations allow us to draw clear-cut conclusions, some limitations of our research must be considered. A first limitation of this study was the focus on only formal learning in that all items regarding previous participation and intention to learn referred to a form of formal learning. By focusing on formal learning we wanted to ensure the reliability of our questionnaire, since formal learning can be described and understood in a very clear and unambiguous way by low-qualified participants and is therefore more explicitly linked to and identified as learning by this particular group. However, past research has shown the value of informal learning (Kyndt et al. 2009b; Tynjälä 2008). Eraut (1994) is one of the many authors who have argued that job-related skills are learned more efficiently in the workplace rather than in formal training, since employees often lack the insight to apply the obtained knowledge in practice. One can wonder if this general observation is—even more than for highly-educated employees—the case for low-qualified employees. It would be, of course, a methodological challenge to measure the learning outcomes of workplace learning and to compare categories of employees. It would also be interesting if future research investigated what low-qualified employees consider to be informal learning, and how this was related to their learning intention.

The next limitation concerns the fact that this is a cross-sectional study which does not allow us to make causal statements about the explored relationships. This research found that learning intentions are related to previous participation in formal job-related learning activities. However, a longitudinal study could investigate whether employees with a higher learning intention participate more in formal job-related learning activities than their colleagues with lower learning intentions. Moreover, the importance of learning intentions, and the opportunities and support offered by the employer for actual participation in learning activities, could be investigated together. Furthermore, this study included different types of organisations (e.g. cleaning companies, messenger services, technical and logistic services, car assembly plants, childcare services and companies from the food industry). Future research could investigate if substantial differences exist between employees working in different types of organisations.

The results of this research identify the vulnerability of low-qualified employees regarding lifelong learning. The most important factors predicting learning intentions—self-efficacy, self-directedness, financial benefits, and job autonomy—are factors that are not associated with low-qualified employees. In accordance with the low-skilled trap noted by Burdett and Smith (2002), it can be argued that the lower positions these employees hold within an organisation do not lead to job autonomy and financial benefits. It is also not evident that these low-qualified employees have high levels of self-efficacy and self-directedness when it comes to learning, due to their educational background (Baert et al. 2006a; Illeris 2006). It is also remarkable that even in a sample of low-qualified people, the group of employees with no diploma appears to be the weakest in terms of lifelong learning participation and learning intentions. In line with Illeris (2006), we could argue that their experience with education was (very) negative, and that this probably caused an aversion or ignorance in terms of learning. The importance of a qualification cannot be stressed sufficiently, and shows that policy makers should keep on investing in programmes to retain students within education, and to prevent early drop out in secondary education. Organisations (and their leaders) should be aware of the vulnerable position of their low-qualified employees when it comes to lifelong learning, since in our continuously changing society it will become increasingly important that this group of employees will also be able to participate in learning activities. So, when offering learning opportunities to low-qualified employees, organisations should also pay attention to how they can enhance the self-efficacy, self-directedness, and job autonomy of low-qualified employees in order to increase their learning intention and willingness to participate in learning activities. It is also a matter of giving better and more personalised information about the available learning opportunities, and guiding low-qualified employees in the articulation process of their learning intention. An additional positive influence can come from clarifying how low-qualified employees can benefit (financially) from participating in learning activities.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Asplund, R., & Salverda, W. (2004). Introduction: company training and services with a focus on low skills. International Journal of Manpower, 25(1), 8–16.

Baert, H. (1998). Het spel van “vormingsbehoeften” en “vormingsnoodzaak” in het levenslang leren. [The game of training needs and training necessity within lifelong learning.]. In J. Katus, J. W. M. Kessels, & P. E. Schedler (Eds.), Andragologie in transformatie [Adult educational theory in transformation.] (pp. 107–118). Meppel: Boom.

Baert, H., De Rick, K., & Van Valckenborgh, K. (2006a). Towards the conceptualisation of learning climate. In R. Vieira de Castro, A. V. Sancho, & P. Guimaraes (Eds.), Adult Education: new routes in a new landscape (pp. 87–111). Braga: University of Minho.

Baert, H., Clauwaert, I., & Wybo, A. (2006b). VTO-perspectieven van werknemers in bedrijven. [Training and development perspectives of employees in companies.]. Leuven: Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.

Baert, H., Philipsen, V., & Clauwaert, I. (2009). Perspectieven en exclusieven voor competentieontwikkeling en levenslang leren van stakeholders in en om arbeidsorganisaties. [Perspectives and exclusivities for competence development and lifelong learning of stakeholders in and for labour organisations]. Leuven: WSE Report 2009.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control (7th ed.). New York: W.H.

Biessen, P. G. A., & de Gilder, D. (1993). BASAM: Basisvragenlijst Amsterdam: Handleiding. Nederland: Swets Test Services.

Boeren, E. (2011). Participation in adult education: A bounded agency approach. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Boeren, E., Nicaise, I., & Baert, H. (2010). Theoretical models of participation in adult education: the need for an integrated model. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 29(1), 45–61.

Brown, K. G. (2005). A field study of employee e-learning activity and outcomes. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 16(4), 465–480.

Burdett, K., & Smith, E. (2002). The low-skilled trap. European Economic Review, 46, 1439–1451.

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Noe, R. A. (2000). Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: a meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 678–707.

Confessore, G. J., & Park, E. M. (2004). Factor validation of the learner autonomy profile, version 3.0 and extraction of the short form. International Journal of Self-directed Learning, 38(1), 39–58.

De Grip, A., & Zwick, T. (2004). The employability of low-skilled workers in the knowledge economy. London School of Economics, LoWER Final Paper.

De Meester, K., Scheeren, J., & Van Damme, D. (2001). Analyse van de barrières voor deelname aan permanente vorming. In H. Baert, M. Douterlunge, D. Van Damme, W. Kusters, I. Van Wiele, T. Baert, M. Wouters, K. De Meester, & J. Scheeren (Eds.), Bevordering van deelname en deelnamekansen inzake arbeidsmarktgerichte permanente vorming (pp. 156–210). Leuven/Gent: CSP-HIVA-UG/VO.

Doornbos, A. J. (2004). Learning at work: Intentionality, developmental relatedness and related work practice characteristics at the Dutch Police Force. Radboud University Nijmegen.

Eisenberger, R., Stinglhamber, F., Vandenberghe, C., Sucharski, I., & Rhoades, L. (2002). Perceived supervisor support: contributions to perceived organisational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 565–573.

European Commission. (2003). Council decision of 22 July 2003 on guidelines for the employment policies of the member states. Official Journal of the European Union, L197, 13–20.

Eraut, M. (1994). Developing professional knowledge and competence. London: Farmer.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

Govaerts, N., Kyndt, E., Dochy, F., & Baert, H. (2011). The influence of learning and working climate on the retention of talented employees. Journal of Workplace Learning, 23(1), 35–55.

Greenhalgh, C., & Mavrotas, G. (1994). The role of career aspirations and financial constraints in individual access to vocational training. Oxford Economic Papers, 46(4), 579–604.

Gropel, P., & Kuhl, J. (2009). Work-life balance and subjective well-being: the mediating role of need fulfillment. British Journal of Psychology, 100(2), 365–375.

Gvaramadze, I. (2010). Low-skilled workers and adult vocational skills-upgrading strategies in Denmark and South Korea. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 62(1), 51–61.

Hazelzet, A., Keijzer, L., & Oomens, S. (2009). Wat prikkelt laagopgeleide werknemers voor schooling? [What stimulates low-qualified employees for schooling?]. Develop: Kwartaaltijdschrift over Human Resources Development, 5(2), 53–60.

Illeris, K. (2006). Lifelong learning and the low-skilled. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 25(1), 15–28.

Keijzer, L., Oomens, S., & Hazelzet, A. (2009). Scholingsintentie van laaggeschoolden. [Learning intention of low-qualified individuals.]. Opleiding en ontwikkeling, 5, 23–26.

Kirschner, P. A., & Thijssen, J. (2005). Competency development and employability. Lifelong learning in Europe, 2, 70–75.

Kyndt, E., Dochy, F., Michielsen, M., & Moeyaert, B. (2009a). Employee retention: organisational and personal perspectives. Vocations & Learning, 2(3), 195–215.

Kyndt, E., Dochy, F., & Nijs, H. (2009b). Learning conditions for non-formal and informal workplace learning. Journal of Workplace Learning, 21(5), 369–383.

Maurer, T. J., & Tarulli, B. A. (1994). Investigation of perceived environment, perceived outcome, and person variales in relationship to voluntary development activity by employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(1), 3–14.

Maurer, T. J., Weiss, E. M., & Barbeite, F. G. (2003). Model of involvement in work-related learning and development activity: the effects of individual, situational, motivational, and age variables. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 707–724.

Noe, R. A., & Wilk, S. L. (1993). Investigation of the factors that influence employees’ participation in development activities. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(2), 291–302.

Noe, R. A., Noe, A. W., & Bachhuber, J. A. (1990). Correlates of career motivation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 37(3), 340–356.

Prince, D. (2008). Tracking low-skill adult students longitudinally: using research to guide policy and practice. New Directions for Community Colleges, 143, 59–69.

Raemdonck, I. (2006). Self-directedness in learning and career processes. A study in lower qualified employees in Flanders. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Universiteit Gent, Gent, Belgium.

Rainbird, H. (2000). Skilling the unskilled: access to work-based learning and the lifelong learning agenda. Journal of Education and Work, 13(2), 183–197.

Renkema, A. (2006). Individual learning accounts: a strategy for lifelong learning? Journal of Workplace Learning, 18(6), 384–394.

Renkema, A., & van der Kamp, M. (2006). The impact of a learning incentive measure on older workers. In T. Tikkanen & B. Nyhan (Eds.), Promoting lifelong learning for older workers. An international overview (pp. 68–89). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Renkema, A., Schaap, H., & van Dellen, T. (2009). Development intention of support staff in an academic organization in The Netherlands. Career Development International, 14(1), 69–86.

Rubenson, K. (1977). Participation in recurrent education. Paris: Centre for Educational Research and Innovations, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67.

Shields, M. (1998). Changes in the determinants of Employer-funded training for full-time Employees in Britain, 1984–1994. The Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 60(2), 189–214.

Silva, T., Cahalan, M., & Lacireno-Paquet, N. (1998). Adult education participation decisions and barriers: Review of conceptual frameworks and empirical studies. Working paper series. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Tharenou, P. (1997). Organisational, job and personal predictors of employee participation in training and development. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46(2), 111–134.

Torka, N., Geurts, P., Sanders, K., & van Riemsdijk, M. (2010). Antecendents of perceived intra-and extra-organisational alternatives. Personnel Review, 39(3), 269–286.

Tynjälä, P. (2008). Perspectives into learning at the workplace. Educational Research Review, 3, 130–154.

Van Dinther, M., Dochy, F., & Segers, M. (2011). Factors affecting students’ self-efficacy in higher education. Educational Research Review. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2010.10.003

Van Veldhoven, M., Meijman, T. F., Broersen, J. P. J., & Fortuin, R. J. (1997). Handleiding VBBA. Onderzoek naar de beleving van psychosociale arbeidsbelasting en werkstress met behulp van de vragenlijst beleving en beoordeling van de arbeid. [Manual VBBA. Research into the perception of psychosocial workload and work stress by means of the questionnaire on the perception and appraisal of work.] Amsterdam: Stichting Kwaliteitsbeoordeling Bedrijfsgezondszorg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Factor Analysis Learning Intention

Factor Matrix

Factor | |

1 | |

I Intend to talk with persons in my surroundings about job-related courses or trainings that I could follow. | .539 |

I intend to participate in a job-related learning activity within the next year. | .758 |

I intend to look for information about job-related courses and learning activities that I could participate in. | .668 |

Sometimes I think about following a job-related training within the next year. | .772 |

I intend to talk with my executive about job-related courses or trainings that I could follow. | .664 |

Extraction Method: Maximum likelihood.

Appendix 2: Factor Analysis Independent Variables: Factors, Items, Factor Loadings, Explained Variance and Reliability

Factor 1: Self-directedness in the career processes (17.70% explained variance, α = .82). | Factor loading |

I find it important to get in touch with people who can be of importance to my career as much as possible. | .685 |

I always think ahead about the steps I have to take in order to reach my career objectives. | .667 |

I find it important to think about what I want to realize in my career during the following years | .657 |

I keep my manager informed on what I want to reach in my career. | .603 |

I think it’s important to think about the progression of my career. | .588 |

I keep myself informed on new possibilities to develop my career. | .540 |

I find it important to consider if my present position in the department and the organisation is the right one. | .455 |

Factor 2: Financial benefits (6.75% explained variance, α = .74). | Factor loading |

I am being paid well for the work I am doing here. | .834 |

In my company the salaries are good. | .592 |

I think my salary is fair in comparison with my colleagues. | .561 |

I can manage easily on my wage. | .536 |

Factor 3: Self-efficacy (5.28% explained variance, α = .80). | Factor loading |

I know for sure that I can persevere in a training or course, even when it’s tough or things do not go my way. | .736 |

I’m sure that I am able to cope with the course. | .688 |

I’m sure that I would be a good member when I would participate in a learning activity. | .631 |

Factor 4: Perceived job autonomy (4.77% explained variance, α = .63). | Factor loading |

I’m free to take decision about how I do my job. | .644 |

I’m free to do my job the way I want. | .615 |

Organising the daily routines of my job is left up to me. | .446 |

Difficult and important tasks at work are also left up to me. | .402 |

Factor 5: Perceived limited number of chances and support (3.97% explained variance, α = .60). | Factor loading |

In this organisation you are not encouraged to take responsibility for your own learning. | .596 |

I did not participate in training because my employer did not support this. | .539 |

I do not get the chance to my job in my own way. | .510 |

I did not participate in training because I did not get the opportunity of my employer. | .497 |

Factor 6: Perceived stimulation by the employer (3.43% explained variance, α = .56). | Factor loading |

I participated in a learning activity because I was stimulated by my employer. | .643 |

I participated in training because I had to in order to keep my function. | .582 |

Extraction Method: Maximum Likelihood.

Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kyndt, E., Govaerts, N., Dochy, F. et al. The Learning Intention of Low-Qualified Employees: A Key for Participation in Lifelong Learning and Continuous Training. Vocations and Learning 4, 211–229 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-011-9058-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-011-9058-5