Abstract

Following on from the recently published articles reported side effects occurring due to donation of stem cells, we describe a case of a donor with transient, biopsy-proved acute focal segmental proliferative glomerulonephritis (GN) due to peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) mobilization with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). A 44-year-old woman with no relevant past medical history suffering from obesity and hypertension well controlled with metoprolol without hypertensive retinopathy was admitted to our hospital as a donor of PBSC. She received G-CSF subcutaneously—filgrastim (Amgen)—at a dose of 5 μg/kg twice a day for 6 days. The macroscopic hematuria and proteinuria occurred on 5th day of G-CSF administration. Due to mobilization and collection of stem cells, proteinuria was becoming more intense and reached the nephrotic range. The immunological, infectious, urological and gynecological causes of such complication were excluded. The final histological recognition was early stage of focal segmental proliferative GN. To our knowledge this a first report of GN in a donor due to mobilization of PBSC confirmed with renal biopsy. These findings suggest that filgrastim may induce transient urinary excretion of protein and hematuria in PBSC donors as the symptoms of acute GN without adversely affecting renal function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The use of peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) following granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) administration for allografting has increased in the last decade in both the related and unrelated settings. Both procedures—bone marrow (BM) and PBSC collections—are inconvenient for donor but generally safe. Adverse events are frequent but most of them are transient, self-limited and without late consequences [1].

The most common short-term complications experienced by PBSC donors following G-CSF administration are bone pain at various sites, fatigue, headache, thrombocytopenia. Serious or even life-threatening events such as atraumatic splenic rupture, acute lung injury, transient respiratory disturbances, cardiovascular complications, bleeding, triggering of inflammatory or autoimmunological diseases and haematological malignancies are sporadic [2–4].

Serious adverse events were more often observed in BM donation as compared with PBSC donation based on report from the NMDP (1.34% in BM donors vs. 0.6% in PBSC donors) [3] but a larger study by the EBMT group proven the opposite results—fatalities and serious events were more frequent due to PBSC donation (0.07% in BM vs. 0.17% in PBSC donors) but generally were less frequent than in the NMDP study [4].

Following on from these articles that reported side effects due to donation of stem cells we describe a case of a donor with transient, biopsy-proved acute focal segmental proliferative glomerulonephritis (GN) due to PBSC mobilization with G-CSF.

2 Case report

In December 2008, a 44-year-old woman with no relevant past medical history suffering from obesity (weight 130 kg, BMI 42.1 kg/m2) and hypertension well controlled with metoprolol without hypertensive retinopathy was admitted to our hospital as a donor of PBSC for transplantation in her fully HLA matched brother diagnosed with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Before mobilization and collection of stem cells we performed standard blood and urine tests and found the asymptomatic microscopic hematuria only in one of three urine tests, which has been never observed before (the urinary sediment contained 3–5 red blood cells/field; no protein, dysmorphic red cells or any casts), mild hypergammaglobulinemia with normal values of immunoglobulins IgA, IgG and IgM among other normal results (including tests detecting viruses: EBV, CMV, HBV, HCV, HIV). The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 90 ml/min/1.73 m2. The ultrasonography of kidneys and urine tract was normal. She had no history of any bacterial or viral infection in the month prior to mobilization of stem cells. She was thus fit to be a stem cells donor and received G-CSF subcutaneously—filgrastim (Amgen)—at a dose of 5 μg/kg twice a day from 4th to 9th December 2008 (total dose 1,260 μg/day), but complaining of bone pain, and was given tramadol (100 mg twice a day orally).

On 8th December—on 5th day of G-CSF administration—painless macroscopic hematuria occurred (the urinary sediment contained 60–70 red cells/field; dysmorphic red cells, few white cells casts, 170 mg/dl of protein). She was not menstruating at the time the gross hematuria was noted.

Stem cells started to be collected on that day and three apheresis (10 l each) with acid citrate dextrose formula—A (ACD-A) as an anticoagulant yielded 651.8 × 106 CD34 positive cells.

During the mobilization and collection proteinuria was becoming more intense and reached the nephrotic range. The 24-h testing for urine protein performed on the last day of apheresis (10th December) revealed 7 g of protein with normal total serum protein and albumin levels and electrophoretic studies of blood and urine. It is interesting that we did not observe any impairment of renal function: azotemia, electrolytes imbalance, oliguria/anuria/polyuria, edema and other complications. GFR was 87 ml/min/1.73 m2. We did not observe serious lipid abnormalities—only mild increased concentration of triglycerides (211 mg/dl).

Moreover, immunological [level of C3 and C4 components of complement; antiglomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic (ANCA) and antinuclear (ANA) antibodies], infectious (HBV; HCV; Mycobacterium tuberculosis with PCR method in urine; anti-streptolysin O assay), urological (ultrasonography of urine tract and urethrocystoscopy) and gynecological causes of such complication were excluded.

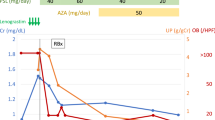

The highest count of white blood cells (WBC) due to G-SCF administration was 67.7 × 109/L (granulocytes 68%) on 9th December. The platelets dropped to the lowest value of 45 × 109/L on 12th December without thrombocytopenic purpura and then increased to a normal value. Her coagulation tests (activated partial thromboplastin time, plasma prothrombin time, fibrinogen, D dimers) were normal. The clinical course is presented in Fig. 1.

She qualified for kidney biopsy which was performed on 18th December 2008.

Light microscopic evaluation revealed the acute, active inflammatory lesions in glomeruli. There was segmental endocapillary increase in cellularity associated with the presence of cellular segmental crescents in 40% (2 out of 5) glomeruli. There was mildly diffuse, focal inflammatory infiltrate in the interstitium, but neither fibrosis nor tubular atrophy was seen. Immunomorphological examination (immunofluorescence) revealed the moderately intense finely granular deposits of IgG, and both light chains (λ, κ) within the mesangial area. There was neither IgA, IgM, C3, nor C1q in glomeruli (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5).

Due to limited amount of tissue the ultrastructural examination was not performed.

The final recognition was early stage of focal segmental proliferative GN.

On the next weeks we were observing self-limited, gradual disappearance of deviations in urine—first hematuria and then proteinuria. After 1 year her renal function and urine tests are normal.

3 Discussion

To our knowledge this a first report of GN due to mobilization of PBSC confirmed with renal biopsy in a donor. Surprisingly, there were discrepant results in the incidences of adverse events due to PBSC versus BM donation between the NMDP and EBMT studies but generally they were uncommon and majority of them were acute and short-lived [3, 4]. Only one PBSC donor reported by the NMDP had a history of microscopic hematuria that progressed to macroscopic hematuria by day 3 of filgrastim administration. By 6 weeks post-donation the macroscopic hematuria had resolved and returned to the baseline level of microscopic hematuria [3].

There are only some reports of biopsy-proved GN which occurred in patients with severe congenital neutropenia treated with long-term filgrastim and required steroids and other agents for control [5, 6].

In our case of a donor we diagnosed focal segmental proliferative GN. In mild cases of this type of GN, clinical presentation may be very scant. The systemic symptomatology is non-specific and may include malaise, sometimes purpura, arthralgia, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinemia (IgA, IgM, and IgG), elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, cryoglobulinemia, and hypertension as a manifestation of a disease. Renal findings include hematuria and proteinuria, sometimes of nephrotic range. Due to only focal and segmental distribution of glomerular lesions, kidneys function is usually not significantly compromised.

Focal segmental proliferative GN is a light microscopic recognition that is defined by the presence of endocapillary hypercellularity in some of glomerular segments. This focal segmental endocapillary proliferation and inflammation may be accompanied by some or all of the following lesions: mesangial hypercellularity, mesangial matrix increase, focal necrosis of glomerular tuft, and extracapillary proliferation (crescents formation).

Focal segmental proliferative GN is not a disease recognition, it is one of the patterns of glomerular injury, that is not specific for a single disease. Both immunomorphological evaluation and clinical data are necessary to formulate the final diagnosis.

Immunomorphological presentation allows for the differentiation between proliferative GN cases that are associated with the presence of immunological complexes in glomerular structures (typical examples include lupus nephritis, IgA nephropathy, post infectious GN) and “pauci immune” cases in which no immunological complexes may be found (most commonly these “pauci immune” cases are a manifestation of ANCA positive small-vessel vasculitis).

The rapidity of onset of the proteinuria and gross hematuria may suggest the presented donor had preexisting renal disease. The microscopic hematuria and hypergammaglobulinemia noted at baseline support this. But pathological findings in kidneys were acute—active without chronic features. There was neither tubulo-interstitial scarring nor pronounced vasculopathy that matched to observed acute evolution of clinical symptoms. There was nothing in the morphological presentation of the disease that would speak for the superimposition of “new” lesions on the preexisted nephropathy. The patient was obese, and she had well controlled hypertension due to all observation, without signs of hypertensive vasculopathy (there was no retinopathy found). None of the glomerular lesions encountered in a donor could be attributed to obesity or hypertension. The typical lesions of obesity-related glomerulopathy include glomerular enlargement and sclerotization. As for the hypertensive nephropathy in its benign form it is defined by the presence of typical chronic vasculopathy, secondary glomerulosclerosis and tubulo-interstitial scarring. Both obesity-related as well as benign hypertension-related nephropathies are chronic ones that are characterized by slow evolution of renal symptoms.

Hematuria and proteinuria were gradually self-limited in our donor after withdraw of G-CSF.

So it seems that changes in the kidney were caused by G-CSF (after exclusion of all other causes). A dose of G-CSF between 10 and 16 μg/kg split into two doses is recommended for mobilization of PBSC. A higher dose results in a higher acute toxicity [7]. Our donor was given a high dose of G-CSF (10 μg/kg/day but greater than 1200 μg/day) because of obesity. G-CSF is known not only to activate neutrophils but also to injure endothelial cells and to modulate cytokine release what may result in vasculitis [8, 9]. All these effects are transient, self-limited and related to drug dose and its administration.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that filgrastim may induce transient urinary excretion of protein and hematuria in PBSC donors as the symptoms of acute GN without adversely affecting renal function. More detailed cases and prolonged follow-up of the donors with such complication are needed to rule out the late renal toxicity of G-CSF.

References

Favre G, Beksac M, Bacigalupo A, Ruutu T, Nagler A, Gluckman E, et al. Differences between graft product and donor side effects following bone marrow or stem cell donation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:873–80.

Tigue CC, McKoy JM, Evens AM, Trifilio SM, Tallman MS, Bennett CL. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor administration to healthy individuals and persons with chronic neutropenia or cancer: an overview of safety consideration from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports Project. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:185–92.

Miller JP, Perry EH, Price TH, Bolan CD Jr, Karanes C, Boyd TM, et al. Recovery and safety profiles of marrow and PBSC donors: experience of the National Marrow Donor Program. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:29–36.

Halter J, Kodera Y, Ispizua AU, Greinix HT, Schmitz N, Favre G, et al. (EBMT) Severe events in donors after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell donation. Haematologica. 2009;94:94–101.

Sotomatsu M, Kanazawa T, Ogawa C, Watanabe T, Morikawa A. Complication of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis in severe congenital neutropenia treated with long-term granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim). Br J Haematol. 2000;110:234–5.

Dale DC, Ottle TE, Fier CJ, Bolyard AA, Bonilla MA, Boxer LA, et al. Severe Chronic neutropenia: treatment and follow up of patients in the Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry. Am J Hematol. 2003;72:82–93.

Kröger N, Zander Ar. Dose and schedule effect of G-CSF for stem cell mobilization in healthy donors for allogeneic transplantation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43(7):1391–4.

Falanga A, Marchetti M, Evangelista V, Manarini S, Oldani E, Giovanelli S, et al. Neutrophil activation and hemostatic changes in healthy donors receiving granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1999;93:2506–14.

Anderlini P, Champlin RE. Biologic and molecular effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in healthy individuals: recent findings and current challenges. Blood. 2008;111:1767–72.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Nasilowska-Adamska, B., Perkowska-Ptasinska, A., Tomaszewska, A. et al. Acute glomerulonephritis in a donor as a side effect of allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell mobilization with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Int J Hematol 92, 765–768 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-010-0730-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-010-0730-6