Abstract

Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) is a potent biologic agent that carries both osteoinductive and osteoconductive properties. Its potential as an autologous bone graft substitute in spine surgery led to its approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2002 following a series of industry-sponsored trials. Although approved for a single level anterior lumbar interbody fusion from L4-S1 with a proprietary cage, the off-label use of rhBMP-2 rapidly escalated. Soon thereafter, reports of serious and potentially life-threatening complications associated with rhBMP-2 began emerging, which sparked concerns with regards to potential bias in the original FDA trials. Ultimately, an independent review of all published and unpublished data on the safety and effectiveness of rhBMP-2 by the Yale University Open Data Access (YODA) Project determined that while rhBMP-2 is as effective as iliac crest bone graft (ICBG) in potentiating spinal fusion, there was significant bias and conflicts of interests that resulted in an underreporting of complications in the original industry-sponsored trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Success with spinal fusion surgery is measured by the ability to achieve a solid arthrodesis and improvement in the patient’s clinical outcomes. Spinal fusion is often dependent upon the bone graft to potentiate the formation of a fusion mass. Autologous iliac crest bone graft (ICBG) is traditionally considered the gold standard for bony augmentation. However, the morbidity associated with ICBG harvest, the limited supply for multilevel fusions, and the variability of graft quality [1, 2] resulted in the development of alternative osteobiologic materials [3–6]. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) is the only bone graft substitute that has demonstrated comparable outcomes to those of ICBG [7]. Following a series of industry-sponsored publications regarding its safety and efficacy, rhBMP-2 (InFUSE; Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN) was approved in 2002 by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a bone graft substitute for a single level anterior lumbar interbody fusion from L4-S1 within a proprietary interbody cage [8]. However, the majority of its clinical applications have been utilized in “off label” settings. As rhBMP-2 gained acceptance and popularity among spine surgeons, reports of devastating complications began to surface. These reports brought into question the integrity of the original industry sponsored trials that led to the FDA approval of InFUSE.

This paper describes the events leading to the FDA approval of rhBMP-2 in spine surgery, examines the potential bias of the original industry-sponsored studies, and recounts the events that prompted a Medtronic-sponsored independent evaluation of all published and unpublished data by the Yale University Open Data Access (YODA) Project.

BMPs

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are members of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) superfamily that regulate cellular differentiation, proliferation, survival, and apoptosis of various tissues and organs [9]. In bone, BMPs regulate bone deposition and cartilage formation by signaling osteoblast differentiation and promoting chondrocyte maturation [10].

Currently, BMP-2 and BMP-7 are available for clinical use in spinal fusion surgery. While BMP-2 is FDA approved, BMP-7 carries only humanitarian device exemption status [11].

Initial studies leading to the FDA approval of rhBMP-2 in spine surgery

Beginning in the 1990s, various animal models demonstrated successful bony induction with the use of BMP-2 [12–16]. However, investigators remained uncertain regarding the appropriate dosage, carriers, and safety of BMP-2, which appeared to be highly variable and dependent upon the animal species and the location within the body [14–17].

In 2000, Boden et al. published the first complete randomized controlled trial that evaluated the feasibility of a rhBMP-2/collagen sponge as a substitute for autologous bone graft utilization in the setting of an ALIF [18]. The authors reported that spinal arthrodesis was more reliable with rhBMP-2 compared with ICBG without any associated adverse events. In 2002, Boden et al. also reported that rhBMP-2, at a dose of 20 mg per side, demonstrated consistent radiographic spinal fusion rates in patients who underwent a posterolateral lumbar fusion (PLF) with or without the use of internal fixation [19]. From 2000 to 2009, a total of 13 published industry-sponsored clinical trials evaluated the efficacy and safety of rhBMP-2 in lumbar and cervical spine surgery (Table 1) [18–30]. These studies enrolled a total of 1580 patients, with 780 patients in the investigational group (rhBMP-2) and 800 patients in the control group (ICBG). In the initial trials, rhBMP2 was delivered in 2 different preparations: InFUSE (1.5 mg/mL of rhBMP-2) and a 33 % more concentrated formulation of AMPLIFY (2.0 mg/mL) [30]. The 1.5 mg/mL concentration of rhBMP-2 used in spine surgery was based on nonhuman primate data and adopted to human use [31].

All of these initial studies reported that rhBMP-2 could potentiate high fusion rates (95.6 % at last follow-up across all fusion techniques). These studies further demonstrated that rhBMP-2 was as effective or superior to ICBG in terms of clinical outcomes and, most importantly, was not associated with any adverse events.

As a result, rhBMP-2 (InFUSE; Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN) was FDA approved in 2002 as a bone graft substitute for a single level ALIF between L4 and S1 within a specific LT-cage (LT-CAGE; Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN) [8]. Initially promoted as an adjunct to spinal arthrodesis in complicated clinical situations, a more widespread off-label utilization of InFUSE ensued. In the United States, the use of InFUSE increased from 0.7 % in 2002 to greater than 25 % of all fusions in 2006 [32]. By the end of 2007, more than 50 % of all primary ALIFs, 43 % of posterior lumbar interbody fusions (PLIF)/transforaminal lumbar interbody fusions (TLIF), and 30 % of posterolateral fusions (PLF) were reportedly performed with InFUSE [15]. Ultimately, 85 % of its utilization was accounted for by off-label administration [33].

Complications associated with the widespread use of InFUSE

Several years following FDA approval, a series of publications surfaced that detailed the serious adverse events associated with InFUSE including heterotopic ossification, osteolysis, seroma/hematoma, infection, allergic reaction, scar formation, arachnoiditis, dysphagia and life threatening retropharyngeal swelling (anterior cervical surgery), increased incidence of neurologic deficits (radiculopathy, myelopathy), retrograde ejaculation, and cancer [34]. In particular, the association between retropharyngeal edema and rhBMP-2 administration in cervical spinal fusion prompted the FDA to issue a Public Health Notification in July 2008 [35]. The FDA had received at least 38 reports, between 2004-2008, regarding the complications associated with rhBMP-2 utilization in the cervical spine that prompted postoperative airway management and second surgery to drain the surgical site. The FDA concluded that the safety and effectiveness of rhBMP-2 in the cervical spine have not been established.

A full list of potential adverse events associated with the use of InFUSE from the FDA Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data is listed in Table 2 [36].

Potential bias in the original BMP-2 industry sponsored studies

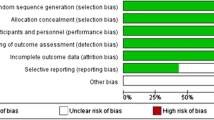

Following the FDA issued Public Health Notification, the Federal Government, Justice Department, and a US Senate Committee launched independent investigations into the off-label use of rhBMP-2 and claims of illegal marketing by Medtronic including “inducements paid to doctors to use InFUSE” [37, 38]. Allegations of inappropriate critical oversight from the publishing medical journals as well as concerns about possible fraudulent data in the original rhBMP-2 publications surfaced in the press [39–42]. In 2011, Carragee et al. [43••] compared the safety and efficacy reports in the original industry-sponsored trials with those of the FDA data summaries, follow-up publications, and administrative databases. The authors noted that the risk of complications and adverse events in patients receiving rhBMP-2 were 10–50 times the original estimates reported in the industry-sponsored publications [43••]. Carragee et al. also concluded that the Level I and Level II evidence from FDA summaries suggested possible study design bias in the original trials.

ICBG control groups

In the original industry-sponsored trials, the safety and efficacy of rhBMP-2 was compared with the “gold standard” ICBG. The rates of complications associated with ICBG administration were unusually high at 40 %–60 %. The latest systematic review of the literature evaluating complications from ICBG harvesting reported an overall morbidity rate of 19.37 % among 6449 total patients [44]. It is believed that the estimates of the morbidity associated with ICBG harvesting in the original industry-sponsored trials were based upon invalid assumptions and methodology. Carragee et al. noted that this reporting bias may have exaggerated the benefits or underestimated the morbidity of rhBMP-2 in the tested clinical situations [43••].

Sample size

The small pilot studies regarding the effectiveness and safety of rhBMP-2 [18, 19, 23] (49 patients in the rhBMP-2 group) carried inadequate sample sizes to assess for safety. However, suggestions of potential adverse events were apparent in at least 1 study. In the other trials with larger sample sizes, evidence of common and potentially serious adverse events of rhBMP-2 also hinted upon. Nonetheless, these complications were failed to be reported [20, 22, 28, 29].

Conflict of interest

In a critical review of the rhBMP-2 pilot studies, Carragee et al. [43••] reported significant financial relationships between the authors of the original 13 FDA trials and Medtronic (Sum, approximately $12,000,000 to $16,000,000; Range, $560,000–$23,500,000 per study). Carragee et al. also demonstrated that for studies reporting on more than 20 patients with rhBMP-2, 1 or more authors had financial relations with Medtronic of more than $1,000,000. In addition, for all studies reporting on more than 100 patients with rhBMP-2, 1 or more authors had financial relations with Medtronic of more than $10,000,000. Carragee et al. noted that the industry sponsored trials failed to clearly describe any reporting bias and the conflict of interest statements appeared to be vague, unintelligible, or internally inconsistent [43••].

Surgical technique

In the industry-sponsored pilot trials comparing rhBMP-2 with ICBG in PLF, there appeared to be significant design bias against the control group [19, 27–30]. In the PLF group, facet preparation was not routinely performed as part of the standard surgical protocol in all patients. Instead, the focus was shifted toward intertransverse process fusion. Upon radiographic analysis, the facet joints were not evaluated for the presence of fusion, which may have biased the clinical outcomes against the ICBG group. Furthermore, the reported rate of radiographic fusion was based upon the presence of bilateral, continuous trabeculated bone connecting the transverse processes. As such, a solid facet fusion alone, often a primary intention of PLF with ICBG, would not have counted as a solid fusion in the ICBG group [43••]. In addition, the surgical protocols involved very small quantities of ICBG (as little as 7 cc) while discarding the remaining local bone graft harvested during the surgery. The disposal of harvested local autograft and the failure to prepare facets for arthrodesis are not standard surgical procedures for PLF and may have significantly biased the outcomes of the ICBG group [43••].

Independent evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of rhBMP-2

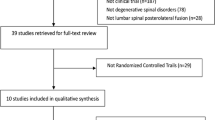

In the wake of the critical review of rhBMP-2 trials by Carragee et al., members of the Senate Committee on Finance issued Medtronic with a deadline to respond to allegations that it had failed to mention side effects or strong financial ties with some of the clinicians involved in the initial trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of rhBMP-2 [45]. In August 2011, Medtronic sponsored a $2.5 million independent review of all published and unpublished data by the Yale University Open Data Access (YODA) Project. Patient-level meta-analyses of data from the Medtronic sponsored randomized controlled trials were obtained and reviewed by 2 separate teams from Oregon Health & Science University and from the University of York in the United Kingdom. The YODA team believed that confidence in the findings would be enhanced if 2 separate independent teams reached the same conclusion. Each team handled one manuscript with neither having access to the other manuscript nor associated review until both were accepted for publication [46].

On June 18, 2013, Annals of Internal Medicine published the findings of the 2 systematic reviews and meta-analyses by the YODA Project [47••, 48•]. The reviewers concluded that the effectiveness of rhBMP-2 with regards to clinical outcomes (ODI scores and SF-36 scores) and fusion rates were comparable with that of ICBG. In addition, when considering safety, the risks of any adverse event were high (77 %–93 % at 2 years) and similar for both groups [48•]. At or shortly following surgery, pain was more common in the rhBMP-2 group (odds ratio, 1.78 [CI, 1.06–2.95]) [47••]. For ALIF, rhBMP-2 was associated with an increase in retrograde ejaculation and urogenital complications, but this was not statistically significant [48•]. Heterotopic bone formation, dysphagia, and osteolysis may be more common with rhBMP-2 [47••]. In anterior cervical spinal fusion, rhBMP-2 was associated with increased risk of wound complications and dysphagia [48•]. At 24 months, cancer risk was increased with rhBMP-2 (RR, 3.45 [95 % CI, 1.98–6.00], however, the event rates were low and the increased risk was no longer apparent at 4 years [7, 48•]. The reviewers also addressed the reporting bias in the Medtronic sponsored studies and concluded that early journal publications misinterpreted the effectiveness and adverse events through selective reporting, underreporting, and duplicate publication [48•].

Conclusions

The clinical use of rhBMP-2 in spinal fusion surgery following FDA approval in 2002 has been a topic of great controversy in the spine community. The YODA trials demonstrated substantial evidence of reporting bias in the original industry-sponsored rhBMP-2 studies. Based on these findings, the role of rhBMP-2 in spinal surgery and its associated risk are still being defined. Further independent, standardized, unbiased research is warranted to better characterize the effectiveness and safety of rhBMP-2 as compared with ICBG.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Abate M, Vanni D, Pantalone A, et al. Cigarette smoking and musculoskeletal disorders. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013;3:63–9.

Grabowski G, Robertson RN. Bone allograft with mesenchymal stem cells: a critical review of the literature. Hard Tissue. 2013;2:20.

Arrington ED, Smith WJ, Chambers HG, et al. Complications of iliac crest bone graft harvesting. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;326:300–9.

Banwart JC, Asher MA, Hassanein RS. Iliac crest bone graft harvest donor site morbidity. A statistical evaluation. Spine. 1995;20:1055–60.

Summers BN, Eistein SM. Donor site pain from the ileum: a complication of lumbar spine fusion. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1989;71:677–80.

Howard JM, Glassman SD, Carreon LY. Posterior iliac crest pain after posterolateral fusion with or without iliac crest graft harvest. Spine J. 2011;11:534–7.

Resnick D, Bozic KJ. Meta-analysis of trials of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: what should spine surgeons and their patients do with this information? Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:912–3.

Food and Drug Administration. InFUSE™ Bone Graft/LT-CAGE™ Lumbar Tapered Fusion Device - P000058. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/DeviceApprovalsandClearances/recently-approveddevices/ucm083423.htm. Accessed 26 Jan 2014.

Ye L, Mason MD, Jiang WG. Bone morphogenetic protein and bone metastasis, implication and therapeutic potential. Front Biosci. 2011;16:865–97.

Blanco Calvo M, Bolós Fernández V, Medina Villaamil V, et al. Biology of BMP signalling and cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:126–37.

Even J, Eskander M, Kang J. Bone morphogenetic protein in spine surgery: current and future uses. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:547–52.

Zdeblick TA, Ghanayem AJ, Rapoff AJ, et al. Cervical interbody fusion cages. An animal model with and without bone morphogenetic protein. Spine. 1998;23:758–65.

Cook SD, Baffes GC, Wolfe MW, et al. The effect of recombinant human osteogenic protein-1 on healing of large segmental bone defects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:827–38.

Gerhart TN, Kirker-Head CA, Kriz MJ, et al. Healing segmental femoral defects in sheep using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein. Clin Orthop. 1993;293:317–26.

Heckman JD, Boyan BD, Aufdemorte TB, et al. The use of bone morphogenetic protein in the treatment of non-union in a canine model. J Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73:750–64.

Simmons DJ, Calhoun JH, Zimmerman B, et al. Effect of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (rhBMP-2) on the healing of cortical bone in the rabbit tibia. Proc Orthop Res Soc. 1994;40:507.

Martin Jr GJ, Boden SD, Marone MA, et al. Posterolateral intertransverse process spinal arthrodesis with rhBMP-2 in a nonhuman primate: important lessons learned regarding dose, carrier and safety. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12:179–86.

Boden SD, Zdeblick TA, Sandhu HS, Heim SE. The use of rhBMP-2 in interbody fusion cages. Definitive evidence of osteoinduction in humans: a preliminary report. Spine. 2000;25:376–81.

Boden SD, Kang J, Sandhu H, Heller JG. Use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 to achieve posterolateral lumbar spine fusion in humans: a prospective, randomized clinical pilot trial: 2002 Volvo Award in clinical studies. Spine. 2002;27:2662–73.

Burkus JK, Gomet MF, Dickman CA, Zdeblick TA. Anterior lumbar interbody fusion using rhBMP-2 with tapered interbody cages. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15:337–49.

Burkus JK, Transfeldt EE, Kitchel SH, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of anterior lumbar interbody fusion using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. Spine. 2002;27:2396–408.

Burkus JK, Heim SE, Gornet MF, Zdeblick TA. Is INFUSE bone graft superior to autograft bone? An integrated analysis of clinical trials using the LT-CAGE lumbar tapered fusion device. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:113–22.

Baskin DS, Ryan P, Sonntag V, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled cervical fusion study using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 with the CORNERSTONE-SR allograft ring and the ATLANTIS anterior cervical plate. Spine. 2003;28:1219–24. discussion 1225.

Haid RW, Branch CL, Alexander JT, Burkus JK. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein type 2 with cylindrical interbody cages. Spine J. 2004;4:527–38. discussion 538–9.

Burkus JK, Sandhu HS, Gornet MF, Longley MC. Use of rhBMP-2 in combination with structural cortical allografts surgery: clinical and radiographic outcomes in anterior lumbar spinal fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1205–12.

Boakye M, Mummaneni PV, Garrett M, et al. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion involving a polyetheretherketone spacer and bone morphogenetic protein. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:521–5.

Dimar JR, Glassman SD, Burkus KJ, Carreon LY. Clinical outcomes and fusion success at 2 years of single-level instrumented posterolateral fusions with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2/compression resistant matrix vs iliac crest bone graft. Spine. 2006;31:2534–9. discussion 2540.

Glassman SD, Dimar JR, Burkus K, et al. The efficacy of rhBMP-2 for posterolateral lumbar fusion in smokers. Spine. 2007;32:1693–8.

Dimar JR, Glassman SD, Burkus JK, et al. Clinical and radiographic analysis of an optimized rhBMP-2 formulation as an autograft replacement in posterolateral lumbar spine arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1377–86.

Dawson E, Bae HW, Burkus JK, et al. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 on an absorbable collagen sponge with an osteoconductive bulking agent in posterolateral arthrodesis with instrumentation. A prospective randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1604–13.

Zara JN, Siu RK, Zhang X, et al. High dose of bone morphogenetic protein 2 induce structurally abnormal bone and inflammation in vivo. Tissue Eng A. 2011;17:1389–99.

Cahill KS, Chi JH, Day A, et al. Prevalence, complications, and hospital charges associated with use of bone-morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA. 2009;302:58–66.

Ong KL, Villarraga ML, Lau E, et al. Off-label use of bone morphogenetic proteins in the United States using administrative data. Spine. 2010;35:1794–800.

Epstein NE. Complications due to the use of BMP/INFUSE in spine surgery: the evidence continues to mount. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4 Suppl 5:S343–52.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Public Health Notification: Life-threatening Complications Associated with Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein in Cervical Spine Fusion. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/alertsandnotices/publichealthnotifications/ucm062000.htm. Accessed 26 Jan 2014.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Summary of Safety and Effectiveness Data. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf/P000058b.pdf. Accessed 27 Jan 2014.

Armstrong D, Burton T. Medtronic says device for spine faces probe. Wall Street J. November 19, 2008. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB122706488112540161. Accessed 26 Jan 2014.

Abelson R. Whistle-blower suit says device maker generously rewards doctors. NY Times. January 24, 2006. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/24/business/24device.html?pagewanted=all. Accessed 26 Jan 2014.

Fauber J. Doctors’ financial stake in Medtronic product questioned. Milwaukee J Sentinel. September 5, 2010. Available at: http://www.twincities.com/ci_15995191. Accessed 26 Jan 2014.

Fauber J. Doctors question journal articles: Medtronic paid surgeons millions for other products. Milwaukee J Sentinel. December 26, 2010. Available at: http://www.jsonline.com/watchdog/watchdogreports/112487909.html. Accessed 26 Jan 2014.

Meier B, Wilson D. Medtronic Bone-Growth Product Scrutinized. NY Times. April 11, 2011. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/12/business/12device.html. Accessed 26 Jan 2014.

Armstrong D. Medtronic Product Linked to Surgery Problems. Wall Street J. September 4, 2008. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB122047307457096289. Accessed 26 Jan 2014.

Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Weiner BK. A critical review of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 trials in spinal surgery: emerging safety concerns and lessons learned. Spine J. 2011;11:471–91. This study compared the conclusions of the safety and efficacy published in the original rhBMP-2 industry-sponsored trials with the FDA data summaries, follow-up publications, and administrative and organizational databases exposing potential conflicts of interest and biases in the studies designs.

Dimitriou R, Matalioakis GI, Angoules AG, et al. Complications following autologous bone graft harvesting from the iliac crest and using the RIA: a systematic review. Injury. 2011;42 Suppl 2:S3–15.

Kmietowicz Z. Senators question Medtronic about unreported side effects of spinal protein. Br Med J. 2011;343:d4284.

Laine C, Guallar E, Murlow C, et al. Closing in on the truth about recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: evidence synthesis, data sharing, peer review, and reproducible research. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:916–8.

Simmonds MC, Brown JV, Heirs MK, et al. Safety and effectiveness of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 for spinal fusion: a meta-analysis of individual-participant data. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:877–89. This was one of the 2 independent reviews of all published and unpublished data on the safety and effectiveness of rhBMP-2 by the Yale University Open Data Access Project concluding that there was no evidence of significant difference between the effectiveness of rhBMP-2 compared with ICBG.

Fu R, Selph S, McDonagh M, et al. Effectiveness and harms of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in spine fusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:890–902. The second of the 2 independent reviews on the safety of rhBMP-2 by the Yale University Open Data Access Project that concluded that early journal publications misinterpreted the effectiveness and adverse events through selective reporting, duplicate publication and underreporting.

Acknowledgments

Sheeraz A. Qureshi has received grant support from the Cervical Spine Research Society.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Branko Skovrlj, Alejandro Marquez-Lara, and Javier Z. Guzman declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Sheeraz A. Qureshi has board membership with MTF, Zimmer SAB, Orthofix SAB, and Pioneer DSM, and has been a consultant for Orthofix; Medtronic; Stryker; and Zimmer.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skovrlj, B., Marquez-Lara, A., Guzman, J.Z. et al. A review of the current published spinal literature regarding bone morphogenetic protein-2: an insight into potential bias. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 7, 182–188 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-014-9221-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-014-9221-3