Abstract

Background

Socioeconomic health disparities research may benefit from further consideration of dispositional factors potentially modifying risk associated with low socioeconomic status, including that indexed by systemic inflammation.

Purpose

This study was conducted to investigate interactions of SES and the Five-Factor Model (FFM) personality traits in predicting circulating concentrations of the inflammatory markers interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP).

Method

Using a sample of middle-aged and older adults from the Midlife in the United States Survey (MIDUS) biomarker project (N = 978), linear regression models tested interactions of each FFM trait with a composite measure of SES in predicting IL-6 and CRP, as well as the explanatory role of medical morbidity, measures of adiposity, and health behaviors.

Results

SES interacted with conscientiousness to predict levels of IL-6 (interaction b = .03, p = .002) and CRP (interaction b = .04, p = .014) and with neuroticism to predict IL-6 (interaction b = −.03, p = .004). Socioeconomic gradients in both markers were smaller at higher levels of conscientiousness. Conversely, the socioeconomic gradient in IL-6 was larger at higher levels of neuroticism. Viewed from the perspective of SES as the moderator, neuroticism was positively related to IL-6 at low levels of SES but negatively related at high SES. Interactions of SES with both conscientiousness and neuroticism were attenuated upon adjustment for measures of adiposity.

Conclusions

Conscientiousness may buffer, and neuroticism amplify, excess inflammatory risk associated with low SES, in part through relationships with adiposity. Neuroticism may be associated with lower levels of inflammation at high levels of SES.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

There is widespread evidence and public recognition of inequalities in health by socioeconomic status (SES) [1, 2]. SES refers to individuals’ position within a hierarchy of social and economic resources, facets or indicators of which include education, income and wealth, and occupational status, among others [3]. SES is related to myriad health outcomes including mortality and partly explains corresponding racial disparities [4]. These associations are typically graded, with each step lower on the socioeconomic ladder associated with poorer outcomes [2]. In spite of such health differentials, there is still substantial heterogeneity in health within lower as well as upper socioeconomic strata [5] and, accordingly, considerable interest in identifying factors associated with relative resilience or susceptibility to the adverse health effects of low SES [6]. Candidate factors in this regard include personality traits, which themselves are consistently linked to physical health outcomes [7, 8] and markers of SES [9].

Personality comprises individuals’ characteristic patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior. In health-related research, it is most often studied using the Five Factor Model (FFM) or “Big Five,” an empirically based taxonomy consisting of five broad domains—neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Conscientiousness (a tendency toward self-discipline, reliability, and orderliness) and neuroticism (proneness to negative emotionality) in particular consistently predict cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, among other outcomes [8, 10–12]. Conscientiousness appears to be a protective factor and neuroticism, a risk factor, although neuroticism is occasionally associated with reduced risk [13–15].

One plausible biological mechanism linking SES and personality with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality is systemic low-grade inflammation, which involves a persistent and generalized (rather than acute and localized) inflammatory response implicated in the pathogenesis of various diseases and disorders [16]. Biomarkers of systemic inflammation, including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP), are key indicators of disease risk in middle age and older adulthood as they are prospectively associated with coronary heart disease [17, 18] as well as diabetes [19], disability [20], and all-cause mortality [21]. SES predicts basal levels of inflammatory markers [22, 23] as well as change in levels over time [24]. With regard to personality, a meta-analysis [25] reported associations of conscientiousness with both IL-6 and CRP, as well as an association of openness with lower CRP. There were no associations of the other big five traits with either marker. In addition to several null findings [26–28], neuroticism has been associated with higher levels of inflammatory markers in multiple studies [29, 30].

In studies of inflammatory markers and other health outcomes, personality and socioeconomic status have been largely examined as independent focal predictors, and there is growing interest in understanding how such dispositional factors and aspects of social stratification interact to influence health [7, 9]. One model of personality-SES interaction, termed selective vulnerability, posits that health-related risk associated with socioeconomic disadvantage may be compounded by certain personality traits (e.g., high neuroticism) but attenuated by others (e.g., high conscientiousness) [8]. The vulnerability model implicitly focuses on SES as the focal risk factor, examining how risk shifts across levels of dispositional characteristics. Such characteristics might serve to buffer or amplify adverse effects of low SES on affective states, health behaviors, and pathophysiologic processes (e.g., autonomic, neuroendocrine, immune) linked to morbidity and mortality [31]. Viewed from the lens of personality as the “primary” risk factor, the same data suggest that trait associations vary across socioeconomic contexts. Consistent with the vulnerability model, studies have reported stronger associations of presumably adaptive (e.g., perceived control) and maladaptive (e.g., neuroticism and negative affectivity) dispositions with physical functioning and mortality at lower levels of SES, thereby contributing to smaller or larger socioeconomic gradients [32–35].

There is some evidence for a similar pattern in relation to inflammation, as a recent study found that dispositional characteristics including perceived control and self-esteem were more strongly associated with lower IL-6, but not CRP, in lower-SES men [36]. However, few studies have investigated interactions of SES with big five or Eysenckian personality traits, and these studies produced somewhat contradictory findings. For instance, in a Scottish cohort study [37], higher neuroticism was associated with higher levels of IL-6 and CRP in persons from high-SES neighborhoods but lower levels in persons from low-SES neighborhoods. In contrast, in a US sample of African-Americans [38], the depression facet of neuroticism was associated with higher CRP in participants with lower education, but lower CRP in those with greater education. Interactions between SES and big five traits in white US adults have not been studied, and there has been little investigation of biobehavioral factors that might explain observed interactions. Additionally, prior studies have examined interactions with dichotomous measures of SES. In the present study, we examined whether a continuous, multi-faceted measure of SES interacted with the big five traits to predict circulating concentrations of IL-6 and CRP in a large US sample. We hypothesized that neuroticism would be more strongly related to higher levels of inflammatory markers at lower levels of SES, thereby contributing to larger socioeconomic gradients at high levels of neuroticism. Conversely, we expected conscientiousness to be more strongly related to lower levels of these markers at lower levels of SES, contributing to smaller gradients at high levels of this trait. We also explored interactions with the remaining big five traits and evaluated the extent to which any observed interactions were explained by medical morbidity, measures of adiposity, and health behaviors.

Method

Participants

Study data were drawn from the Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) study, which commenced in 1995 and recruited a national random digit dial sample of approximately 7000 English-speaking adults of ages 25 to 74. A follow-up survey (MIDUS II) was conducted between 2004 and 2006, with an average interval of 9 (7.8 to 10.4) years. A total of 4963 individuals participated in MIDUS II, representing a total mortality-adjusted response rate of 75 %. A subset of MIDUS I and II participants (N = 1054, 43.0 % response rate) subsequently participated in a biomarker project conducted between 2004 and 2009 and completed on average 2.8 years after the MIDUS II survey. The biomarker study involved an overnight visit at one of three clinical research centers and included a physical exam, medical history, collection of biological samples, and a self-administered questionnaire. A detailed description of biomarker study procedures is available elsewhere [39]. Love and colleagues [39] reported that the biomarker sample was comparable to the broader MIDUS II sample on age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, and income, although participants were more likely to have a college degree (p < .01). Biomarker participants were also similar on most health-related characteristics, but were less likely to smoke (p < .01). Approximately 93 % of participants (N = 978) had complete data on all variables in this study. Those with missing data had lower levels of CRP, t (98.2) = −2.38, p = .010, d = .27, but were otherwise comparable to those with complete data.

Measures

Sociodemographic Covariates

Sociodemographic covariates included age, gender, and race/ethnicity (coded as a dummy variable comparing non-Hispanic whites to all participants of minority race/ethnicity).

Inflammatory Markers

IL-6 was measured from serum using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and CRP from plasma with a particle enhanced immunonepholometric assay (BNII nephelometer from Dade Behring, Deerfield, IL). The laboratory intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variance were in acceptable ranges for IL-6 (3.25 and 12.31 %) and CRP (4.4 and 5.7 %). A base-10 logarithm transformation was applied to IL-6 and CRP variables to reduce skew in the distributions. Although CRP values exceeding 10.0 mg/L may reflect acute inflammation due to current infection or injury, results of prior studies suggest that discarding these cases may result in a loss of meaningful outcome variance [40]. Therefore, as in prior studies [25], CRP values above 10.0 mg/L were retained (31 cases, with a mean of 21.5 and range of 10.4 to 61.7 mg/L) in primary analyses. We also performed sensitivity analyses truncating values at 10.0 mg/L and excluding them altogether.

Socioeconomic Status

An equally weighted composite measure of socioeconomic status was constructed by averaging standardized scores (z-scores) on education, household income, and occupational prestige. Composite or latent measures of SES capture the aggregate effects of multiple socioeconomic indicators and are therefore useful in investigating a general gradient of socioeconomic position [3, 41]. In supplementary analyses, we examined each indicator of SES separately. Educational attainment was measured on a 12-point scale (e.g., 1 = no school/some grade school; 5 = high school degree; 9 = 4-year college degree/B.A., 12 = advanced graduate/professional degree). Past (if retired or unemployed) or current occupational status was measured using the Duncan socioeconomic index (SEI) score, a rating of occupational prestige based on data from the General Social Survey [42]. Total household income was calculated in MIDUS by summing reported annual income from all sources (i.e., employment, social security, investments, etc.) and was adjusted for household size.

Personality Traits

Big five personality traits were measured using the Midlife Development Inventory (MIDI) Personality Scales [43]. Respondents were asked to rate the extent to which each of 26 adjectives described themselves on a scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“a lot”). Items were drawn from existing trait adjective inventories and selected based on pilot study data [43]. Five adjectives measure extraversion (outgoing, friendly, lively, active, talkative), agreeableness (helpful, warm, caring, softhearted, sympathetic) and conscientiousness (organized, responsible, hardworking, careless, and thorough), four measure neuroticism (moody, worrying, nervous, calm), and seven measure openness (creative, imaginative, intelligent, curious, broadminded, sophisticated, and adventurous). Trait scores are calculated by taking the mean across each set of adjectives, after reverse scoring applicable items.

Internal consistency alphas in the analytic sample were as follows: neuroticism = .76, extraversion = .78, openness = .77, agreeableness = .82, and conscientiousness = .70. The MIDI personality scales show the expected five-factor structure and demonstrate measurement invariance across age groups [44]. With regard to construct validity, the MIDI scales are moderately to highly correlated (.6–.8) with the corresponding scales from the NEO personality inventory short form (NEO-PI-SF), although the correlation of MIDI agreeableness with NEO agreeableness was weaker (.42) and comparable to its correlation (.38) with NEO extraversion [45]. The lower convergent validity for agreeableness has been attributed to representation of only two NEO facets (trust and altruism) in the MIDI measure [45].

Health Covariates

All health-related covariates were measured at the biomarker study clinic visit. Medical morbidity was measured using the total self-reported number of up to 14 doctor-diagnosed medical conditions (e.g., heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer) associated with either IL-6 or CRP in bivariate analyses. Given the low frequency counts for scores greater than 6 and resulting skew, these scores were winsorized at a value of 6. Dummy variables were used to adjust for current self-reported use of antihypertensive and cholesterol medications [40]. Smoking status was measured as a three-category variable, with dummy variables comparing former and current smokers to lifetime non-smokers. Hours per week of exercise were measured as a weighted average of light (e.g., “light housekeeping”; 1 × number of hours), moderate (e.g., “brisk walking”; 2 × number of hours), and vigorous activities (e.g., “high-intensity aerobics”; 3 × number of hours), accounting for seasonal variation [36]. Finally, to capture maximal variance in body mass and adiposity potentially associated with inflammation, we included both body mass index (BMI: kg/m2) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), which were only moderately correlated (.34) in the analytic sample. BMI was calculated from height and weight and WHR from waist and hip circumference measured at the clinic visit.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated a series of linear regression models testing interactions of big five personality traits with the SES composite in predicting IL-6 and CRP. Baseline models included age, gender, race, SES, a given personality trait, and the applicable interaction term. In case of a significant interaction, we proceeded to examine the simple slopes for associations of SES with inflammatory markers at different levels of personality traits using standard methods [46], as well as the regions of significance, or ranges of the moderator variable within which the predictor of interest is significantly related to the outcome. We also examined observed interactions from the alternate perspective, considering SES as the moderator. Finally, we examined whether the interaction term and simple slopes were altered upon further adjustment for chronic disease burden and medication use, health behaviors, and measures of adiposity. Since health-related covariates were measured at the same time as the inflammatory markers, we sought simply to determine whether they explained observed associations, as in prior studies [47] remaining agnostic regarding their status as mediators or confounders. Personality and SES variables were standardized, such that coefficients reflect the change in log-transformed inflammatory markers associated with a difference of one standard deviation in the predictor.

Models were estimated with cluster-robust standard errors due to the inclusion of 260 sets of twins or siblings in the analytic sample. To account for the increased type I error rate resulting from multiple statistical tests, we utilized the false discovery rate technique (FDR; [48]. The FDR controls type I error for multiple tests without the loss of power and inflation in type II error rate that occurs with the use of Bonferroni and other family-wise error corrections. We set a false discovery rate of 5 %, accounting for the possibility that 5 % of significant results among the ten personality-SES interactions tested would be false positives. Using the FDR, a test is considered significant if the p value is less than a corrected overall critical p value. To avoid confusion, we note that the ensuing analysis of simple slopes and graphing of regions of significance employed the standard .05 alpha level. Supplementary analyses examined interactions involving each indicator of SES separately. In addition, we performed a sensitivity analysis in which all personality traits and interactions with SES were included in a single model.

We also performed additional sensitivity analyses (a) testing whether any interaction of neuroticism and SES would persist after adjustment for a previously reported neuroticism-by-conscientiousness interaction for IL-6 [47], (b) truncating and omitting CRP values over 10 mg/L, and (c) using robust regression to evaluate the impact of any outliers on estimates. Analyses were performed using Stata (Version 14, StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Descriptive statistics for the sample are shown in Table 1. Study participants ranged in age from 35 to 86, with an average age of approximately 58.0 (SD = 11.6). The sample was predominantly white (93 %) and relatively well educated, with nearly 50 % having a college degree. Personality traits were weakly correlated with SES indicators, and were related to health covariates in expected directions (as shown in Electronic Supplementary Material 1). Log-transformed IL-6 and CRP were correlated at .50. Neuroticism and conscientiousness were negatively correlated with IL-6, whereas agreeableness was positively correlated with CRP.

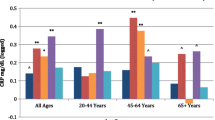

In baseline models adjusted for age, gender, and race, there were statistically significant interactions between SES and conscientiousness in predicting both IL-6 (b = .03 [95 % CIs .02–.05], p = .002) and CRP (b = .04 [.01–.07], p = .014), shown in Table 2. As hypothesized, simple slopes indicated that inverse associations of SES with both markers decreased in magnitude with increasing conscientiousness and were statistically significant only at the mean level of conscientiousness (IL-6: b = −.02 [−.04 to −.00], p = .047; CRP: b = −.04 [−.07 to −.01], p = .023) and below. In other words, associations of lower SES with higher IL-6 and CRP were attenuated at high levels of conscientiousness. Figure 1 shows the SES regression coefficient and 95 % confidence interval (CI) for IL-6 at varying levels of the moderator conscientiousness; regions of significance (in which coefficients are significant at an alpha level of .05) occur across the range of conscientiousness values (X-axis) where the 95 % CI does not include zero. When considering SES as the moderator, associations of conscientiousness with lower levels of both markers were stronger at lower SES, with significant associations at or below the mean SES (at the mean for IL-6: b = −.03 [−.05 to −.02], p < .001; for CRP: b = −.03 [−.06 to −.00], p = .07).

As shown in Table 3, there was a significant interaction of SES and neuroticism in the baseline model predicting IL-6 (b = −.03 [−.05 to −.01], p = .004). The same interaction in the model for CRP (b = −.04 [−.07 to −.01], p = .021) approached but did not reach significance based on the FDR-adjusted critical value (which corresponded to p < .015). Simple slopes indicated that the association between higher SES and lower IL-6 increased in magnitude with increasing levels of neuroticism, and was statistically significant only at levels of neuroticism at or above the mean (b = −.02 [−.04 to −.00], p = .045). Figure 2 shows these coefficients and associated regions of significance. When considering neuroticism as the predictor and SES as the moderator, neuroticism was associated with higher IL-6 at lower levels of SES but lower IL-6 at higher levels of SES. These associations were statistically significant at 1.5 SD below the mean of SES (b = .02 [.00–.08]. p = .049) and 0.75 SD above the mean of SES (b = −.02 [−.05 to −.00], p = .044), respectively. The interaction trend for CRP showed a similar pattern of associations.

Regarding other big five traits, an interaction of extraversion and SES in predicting IL-6—in which the inverse association of SES with IL-6 was stronger at low levels of extraversion, and vice versa—approached but did not reach significance (b = .02 [.00–.04], p = .026). There were no interactions of SES with extraversion predicting CRP, or with openness or agreeableness predicting either marker (not shown, all ps > .50).

Interactions of SES and conscientiousness in predicting both inflammatory markers were modestly attenuated (20–30 %) upon adjustment for all covariates, with measures of adiposity accounting for nearly all of this attenuation. The main effect of SES (at the mean of conscientiousness) was attenuated by 65 % for both IL-6 and CRP. The interaction of neuroticism with SES was more substantially attenuated (40 %) in the fully adjusted model, with measures of adiposity again reducing the coefficient to the greatest extent (30 %). The main effect of SES (at the mean of neuroticism) was also attenuated by two thirds.

Supplementary analyses examining interactions of neuroticism and conscientiousness with separate indicators of SES showed that interactions with income were generally weaker, being only marginally significant or non-significant. Education interacted with both traits to predict IL-6, but not with conscientiousness in relation to CRP. All interactions involving occupational prestige were significant. In a sensitivity analysis in which all traits and interactions with SES were included in a single model (as shown in Electronic Supplementary Material 2), coefficients for neuroticism-by-SES interactions were approximately 20–30 % smaller, likely attributable to some overlap of neuroticism with other personality traits. In contrast, coefficients for conscientiousness-by-SES interactions were unchanged. Two of the three significant interactions (neuroticism-by-SES for IL-6 and conscientiousness-by-SES for CRP) no longer reached the more stringent FDR-adjusted critical value, but remained significant according to the conventional alpha .05 threshold. Taken together, results of primary and sensitivity analyses indicated that interactions of SES with conscientiousness were most robust, whereas the evidence for unique interactions of SES with neuroticism was somewhat more modest.

In other sensitivity analyses, coefficients for interactions of N and SES in predicting IL-6 and CRP were minimally attenuated upon further adjustment for interactions of neuroticism and conscientiousness, which were significant for IL-6 (b = −.03 [−.04 to −.01]; p = .005) but not for CRP (b = −.004 [−.03–.03], p = .80). Results from analyses truncating and excluding values of CRP exceeding 10.0 mg/L were highly similar (all interaction ps < .05), as were results from robust regression models (minimal changes in estimates or p values).

Discussion

Using a national sample of middle-aged and older adults, we found that socioeconomic status interacted with conscientiousness and neuroticism to predict circulating concentrations of inflammatory markers. Socioeconomic gradients in both IL-6 and CRP were smaller at higher levels of conscientiousness. Viewed alternately, associations between higher conscientiousness and lower levels of both inflammatory markers were stronger at lower levels of SES. In contrast to results for conscientiousness, the socioeconomic gradient in IL-6 was larger at higher levels of neuroticism. Greater neuroticism was related to higher IL-6 at low SES, but lower IL-6 at high SES, contributing to a larger SES differential. A similar trend was observed in relation to CRP.

Other studies have reported smaller socioeconomic gradients in IL-6 and mortality at higher levels of psychological resources including perceived control [32, 36]. Here we observed a similar interaction involving conscientiousness, a well-established predictor of health outcomes over the lifespan [49, 50] that has attracted attention as a possible target for intervention [51]. Findings of these studies suggest that conscientiousness may be particularly beneficial to health at lower levels of SES. Even in this context, however, it should not be assumed that conscientiousness and related traits are universally protective as studies have linked high conscientiousness with greater decrease in life satisfaction upon unemployment [52], self-control with a marker of greater cellular aging in low-income, rural African-American youth [53], and active coping (“John Henryism”) with elevated blood pressure in African-American men [54].

In this study, interactions of SES with conscientiousness were partly attenuated by measures of adiposity (BMI and waist-to-hip ratio). In prior studies BMI partly explained independent associations of both SES and conscientiousness with markers of inflammation [25, 55]. Taken together, these findings suggest that conscientiousness is related to lower inflammation through protective effects on body mass/adiposity, and that these indirect effects may be stronger at lower levels of SES. It may be that the self-discipline associated with conscientiousness is especially protective against excess adiposity and corresponding inflammation in low-SES contexts in which obesity and overweight are more prevalent [56]. SES-conscientiousness interactions persisted after adjustment for medical morbidity, smoking, and exercise, suggesting the involvement of unmeasured behaviors or other factors. For instance, individuals who are higher in conscientiousness report lower levels of stress [50] and more effective coping styles [57], which might protect against stress-induced systemic inflammation in low-SES circumstances characterized by greater prevalence and severity of stressors [31].

Findings suggest that neuroticism is a risk factor for systemic inflammation at low levels of SES, but a protective factor at high levels of SES, resulting in larger socioeconomic gradients in inflammation at high levels of this trait. While the opposite pattern of interaction was observed in a Scottish cohort [37], a similar pattern involving a measure of trait depression emerged in a sample of African-Americans [38]. A study in a UK cohort [58] also indicated higher neuroticism-related risk for cardiovascular mortality at low SES but lower risk at high SES (with inflammation being a plausible biological mechanism), albeit only in women (a post hoc probe of three-way interactions revealed no such gender difference here). In the present study, associations of neuroticism with higher IL-6 appeared only at a low level of SES relative to the sample distribution, which may be due in part to the relatively high average SES in this cohort. The interaction of SES and neuroticism predicting CRP was comparable in magnitude to that for IL-6, but did not reach statistical significance on account of a larger standard error. This greater statistical “noise” appears consistent with the relative position of IL-6 and CRP in the cascade of systemic inflammatory processes, with the latter occurring further downstream [16].

Evidence from prior studies supports the notion that neuroticism may have a salutary influence on health under certain conditions. High neuroticism combined with high conscientiousness, a configuration termed “healthy neuroticism” [59] has been linked to lower IL-6 [47], fewer alcohol problems [60], and less smoking [61]. Here, interactions of neuroticism with SES were independent of interactions with conscientiousness. It may be that anxiety emanating from neuroticism is protective in high-SES contexts frequently characterized by high health literacy, supportive social norms, and ample material resources.

The SES-neuroticism interaction predicting IL-6 was partly attenuated upon adjustment for health-related covariates, with BMI and waist-to-hip ratio accounting for most of this reduction. This result suggests that associations of neuroticism with adiposity, and inflammation in turn, may differ depending on SES. Indeed, a post hoc test revealed a statistically significant interaction (b = −.08, p = .008) in which neuroticism was related to higher BMI at lower SES, but lower BMI at higher SES. Poor dietary habits including emotional eating may be a means of coping with chronic negative affect in low-SES contexts characterized by higher stress and lower health literacy. In contrast, socioeconomic resources may facilitate healthier coping behaviors related to lower body weight including exercise and a healthier diet. Other unmeasured factors such as health monitoring, medical service use or treatment adherence may also be involved [58].

In this study, we found no interactions of SES with the other big five traits—extraversion, agreeableness, and openness—in predicting either inflammatory marker, although there was a trend in which extraversion was related to lower IL-6 at lower but not higher levels of SES.

Chapman and colleagues [26] previously reported that extraversion was associated with lower IL-6 in a low-SES primary care sample, and thus further study may be warranted. With regard to specific socioeconomic indicators, interactions were generally stronger for education and occupational prestige and weaker for income. Thus, it appears that differential associations of personality traits with inflammatory markers by SES are not merely a function of the relative extent of material resources. Rather, they may also depend on other SES-related resources and risks including health literacy, access to health care and social capital, and work-related stress.

Findings of this study have several implications. From a theoretical standpoint, they extend the evidence for a vulnerability model of personality-SES interaction [8]. Individuals high in conscientiousness appear less prone to the excess inflammatory burden associated with socioeconomic disadvantage: high levels of this trait might compensate for lower levels of social, material, or other resources for health, and blunt the impact of disproportionate risk exposure. In contrast, individuals low in SES and high in neuroticism may be at greatest risk for systemic inflammation. In individuals of high SES, however, high neuroticism may actually be protective, perhaps helping to explain sporadic associations of neuroticism with lower mortality appearing in the literature [13–15]. Future studies of cardiovascular and other health outcomes should consider screening for interactions of neuroticism with SES indicators, as overall associations may underestimate and overestimate risk in persons of lower and higher SES, respectively [58].

From a translational perspective, considering personality traits in conjunction with socioeconomic status may ultimately help to identify those most prone to systemic inflammation. Additionally, motivational and behavioral interventions to enhance conscientiousness have garnered interest [50, 51], as have cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological interventions to reduce neuroticism [51, 62, 63]. Findings of this study suggest that such interventions may have the greatest benefits in reducing inflammation in individuals of lower SES. Furthermore, they raise the question as to whether enhancing conscientiousness among those lower in SES might contribute to smaller socioeconomic differentials in inflammation.

Findings of this study should be interpreted in consideration of both study strengths and limitations. Inflammatory markers were measured at a single time point, and thus we could not discern whether interactions of SES and personality traits predict changes in levels of these markers over time. Although the predictors were measured a few years prior to the outcomes, some degree of bidirectional causality is possible if inflammation influences affect and motivation over extended periods of time, thereby affecting personality [25]. Health-related covariates and inflammatory markers were measured contemporaneously, and thus whether the former variables were mediators or confounders could not be ascertained [46]. In addition, levels of adiposity may have partly resulted from as well as contributed to inflammation [16].

An important limitation is that the measure of neuroticism used in this study primarily taps the anxiety facet of this trait [30]. Additional research is needed to determine whether the observed interactions extend to other facets of neuroticism previously correlated with inflammatory markers, including anger/hostility, vulnerability, and impulsivity [30]. Another set of limitations pertains to the study sample, which is not nationally representative. As such, caution should be exercised in generalizing these findings. More specifically, in addition to being predominantly white the sample features a relatively high average level of education. Likely as a result of reduced socioeconomic diversity, SES was more weakly correlated with conscientiousness than is sometimes the case [64]. Thus, the extent to which results extend to racial/ethnic minorities and to more socioeconomically disadvantaged populations is unknown. Strengths of the study include a large, nationally recruited sample, as well as the use of multiple indicators of SES and markers of inflammation.

In summary, we found that socioeconomic gradients in inflammatory markers in middle-aged and older adults were attenuated at high levels of conscientiousness (an apparent protective factor at low SES) but further accentuated at high levels of neuroticism, which may be a risk factor at low SES but a protective factor at high SES. Further research is needed to identify specific facets of these traits involved in interactions with SES, to clarify underlying mechanisms, and to further assess implications for intervention and prevention efforts.

References

Adler NE, Stewart J. Health disparities across the lifespan: Meaning, methods, and mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):5–23.

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S186-S196.

Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(1):7–12.

Thorpe Jr RJ, Koster A, Bosma H, et al. Racial differences in mortality in older adults: Factors beyond socioeconomic status. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(1):29–38.

Chen E, Miller GE. Socioeconomic status and health: Mediating and moderating factors. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:723–749.

Whitfield KE, Bogart LM, Revenson TA, France CR. Introduction to special section on health disparities. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(1):1–3.

Murray AL, Booth T. Personality and physical health. Curr Opin Psychol.2015;5:50–55.

Chapman BP, Roberts B, Duberstein P. Personality and longevity: Knowns, unknowns, and implications for public health and personalized medicine. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:759170.

Chapman BP, Fiscella K, Kawachi I, Duberstein PR. Personality, socioeconomic status, and all-cause mortality in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(1):83–92.

Friedman HS, Kern ML. Personality, well-being, and health. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65(1):719–742.

Turiano NA, Chapman BP, Gruenewald TL, Mroczek DK. Personality and the leading behavioral contributors of mortality. Health Psychol. 2015;34(1):51–60.

Jokela M, Pulkki-Raback L, Elovainio M, Kivimaki M. Personality traits as risk factors for stroke and coronary heart disease mortality: Pooled analysis of three cohort studies. J Behav Med. 2014;37(5):881–889.

Weiss A, Costa Jr PT. Domain and facet personality predictors of all-cause mortality among medicare patients aged 65 to 100. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(5):724–733.

Friedman HS, Kern ML, Reynolds CA. Personality and health, subjective well-being, and longevity. J Pers. 2010;78(1):179–216.

Ploubidis GB, Grundy E. Personality and all cause mortality: Evidence for indirect links. Pers Indiv Dif. 2009;47(3):203–208.

Bennett JM, Gillie BL, Lindgren ME, Fagundes CP, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Inflammation through a psychoneuroimmunological lens. In: Handbook of systems and complexity in health. Springer; 2013:279–299.

Danesh J, Wheeler JG, Hirschfield GM, et al. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(14):1387–1397.

Danesh J, Kaptoge S, Mann AG, et al. Long-term interleukin-6 levels and subsequent risk of coronary heart disease: Two new prospective studies and a systematic review. PLoS medicine. 2008;5(4):e78.

Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286(3):327–334.

Ferrucci L, Harris TB, Guralnik JM, et al. Serum IL-6 level and the development of disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(6):639–646.

Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, et al. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am J Med. 1999;106(5):506–512.

Herd P, Karraker A, Friedman E. The social patterns of a biological risk factor for disease: Race, gender, socioeconomic position, and C-reactive protein. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2012;67(4):503–513.

Nazmi A, Victora CG. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic differentials of C-reactive protein levels: A systematic review of population-based studies. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):212.

Janicki-Deverts D, Cohen S, Kalra P, Matthews KA. The prospective association of socioeconomic status with C-reactive protein levels in the CARDIA study. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(7):1128–1135.

Luchetti M, Barkley JM, Stephan Y, Terracciano A, Sutin AR. Five-factor model personality traits and inflammatory markers: New data and a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;50:181–193.

Chapman BP, Khan A, Harper M, et al. Gender, race/ethnicity, personality, and interleukin-6 in urban primary care patients. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(5):636–642.

Chapman BP, van Wijngaarden E, Seplaki CL, Talbot N, Duberstein P, Moynihan J. Openness and conscientiousness predict 34-SSweek patterns of interleukin-6 in older persons. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25(4):667–673.

Mottus R, Luciano M, Starr JM, Pollard MC, Deary IJ. Personality traits and inflammation in men and women in their early 70s: The lothian birth cohort 1936 study of healthy aging. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(1):11–19.

Armon G, Melamed S, Shirom A, Berliner S, Shapira I. The associations of the five factor model of personality with inflammatory biomarkers: A four-year prospective study. Pers Individ Dif. 2013;54(6):750–755.

Sutin AR, Terracciano A, Deiana B, et al. High neuroticism and low conscientiousness are associated with interleukin-6. Psychol Med. 2010;40(09):1485–1493.

Matthews KA, Gallo LC. Psychological perspectives on pathways linking socioeconomic status and physical health. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:501.

Turiano NA, Chapman BP, Agrigoroaei S, Infurna FJ, Lachman M. Perceived control reduces mortality risk at low, not high, education levels. Health Psychol. 2014;33(8):883–890.

Jaconelli A, Stephan Y, Canada B, Chapman BP. Personality and physical functioning among older adults: The moderating role of education. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(4):553–557.

Lazzarino AI, Hamer M, Stamatakis E, Steptoe A. The combined association of psychological distress and socioeconomic status with all-cause mortality: A national cohort study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173(1):22–27.

Lazzarino AI, Hamer M, Stamatakis E, Steptoe A. Low socioeconomic status and psychological distress as synergistic predictors of mortality from stroke and coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(3):311–316.

Elliot, A.J. & Chapman, B. P. Socioeconomic status, psychological resources, and inflammatory markers: Results from the MIDUS study. Health Psychol. 2016; doi: 10.1037/hea0000392.

Millar K, Lloyd SM, McLean JS, et al. Personality, socio-economic status and inflammation: Cross-sectional, population-based study. PloS one. 2013;8(3):e58256.

Mwendwa DT, Ali MK, Sims RC, et al. Dispositional depression and hostility are associated with inflammatory markers of cardiovascular disease in African Americans. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;28:72–82.

Love GD, Seeman TE, Weinstein M, Ryff CD. Bioindicators in the MIDUS national study: Protocol, measures, sample, and comparative context. J Aging Health. 2010;22(8):1059–1080.

O’Connor M, Bower JE, Cho HJ, et al. To assess, to control, to exclude: Effects of biobehavioral factors on circulating inflammatory markers. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(7):887–897.

Senn TE, Walsh JL, Carey MP. The mediating roles of perceived stress and health behaviors in the relation between objective, subjective, and neighborhood socioeconomic status and perceived health. Ann Behav Med. 2014:1-10.

Hauser RM, Warren JR, eds. Socioeconomic indexes for occupations: A review, update, and critique. 1996. Retrieved from http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/cde/cdewp/96–01.pdf.: University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Demography & Ecology Working Paper No. 96–01.

Lachman M, Weaver SL. The midlife development inventory (MIDI) personality scales: Scale construction and scoring. (Tech. Rep. No.1). 1997. http://www.brandeis.edu/departments/psych/lachman/pdfs/midi-personality-scales.pdf

Zimprich D, Allemand M, Lachman ME. Factorial structure and age-related psychometrics of the MIDUS personality adjective items across the life span. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(1):173–186.

Lachman, ME. Addendum for MIDI personality scales. MIDUS II version. 2005. http://www.brandeis.edu/departments/psych/lachman/pdfs/revised-midi-scales.pdf

Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991.

Turiano NA, Mroczek DK, Moynihan J, Chapman BP. Big 5 personality traits and interleukin-6: Evidence for “healthy neuroticism” in a US population sample. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;28:83–89.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995:289-300.

Hampson SE, Edmonds GW, Goldberg LR, Dubanoski JP, Hillier TA. Childhood conscientiousness relates to objectively measured adult physical health four decades later. Health Psychol. 2013;32(8):925.

Bogg T, Roberts BW. The case for conscientiousness: Evidence and implications for a personality trait marker of health and longevity. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013;45(3):278–288.

Chapman BP, Hampson S, Clarkin J. Personality-informed interventions for healthy aging: Conclusions from a national institute on aging work group. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(5):1426.

Boyce CJ, Wood AM, Brown GD. The dark side of conscientiousness: Conscientious people experience greater drops in life satisfaction following unemployment. J Res Pers. 2010;44(4):535–539.

Miller GE, Yu T, Chen E, Brody GH. Self-control forecasts better psychosocial outcomes but faster epigenetic aging in low-SES youth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(33):10325–10330.

Subramanyam MA, James SA, Diez-Roux AV, et al. Socioeconomic status, John Henryism and blood pressure among African-Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. Soc Sci Med. 2013;93:139–146.

Ranjit N, Diez-Roux AV, Shea S, Cushman M, Ni H, Seeman T. Socioeconomic position, race/ethnicity, and inflammation in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2007;116(21):2383–2390.

McLaren L. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:29–48.

Connor-Smith JK, Flachsbart C. Relations between personality and coping: A meta-analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;93(6):1080.

Hagger-Johnson G, Roberts B, Boniface D, et al. Neuroticism and cardiovascular disease mortality: Socioeconomic status modifies the risk in women (UK health and lifestyle survey). Psychosom Med. 2012;74(6):596–603.

Friedman HS. Long-term relations of personality and health: Dynamisms, mechanisms, tropisms. J Pers. 2000;68(6):1089–1107.

Turiano NA, Whiteman SD, Hampson SE, Roberts BW, Mroczek DK. Personality and substance use in midlife: Conscientiousness as a moderator and the effects of trait change. J Res Pers. 2012;46(3):295–305.

Weston SJ, Jackson JJ. Identification of the healthy neurotic: Personality traits predict smoking after disease onset. J Res Pers. 2015;54:61–69.

Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 2009;64(4):241–256.

Armstrong L, Rimes KA. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for neuroticism (stress vulnerability): A pilot randomized study. Behav Ther. 2016;47(3): 287–298.

Roberts BW, Kuncel NR, Shiner R, Caspi A, Goldberg LR. The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2(4):313–345.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Author’s Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Authors Elliot, Turiano, and Chapman declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Data used for this research was provided by the longitudinal study titled “Midlife in the United States,” (MIDUS) managed by the Institute on Aging, University of Wisconsin. This research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166; R01AG044588).

About this article

Cite this article

Elliot, A.J., Turiano, N.A. & Chapman, B.P. Socioeconomic Status Interacts with Conscientiousness and Neuroticism to Predict Circulating Concentrations of Inflammatory Markers. ann. behav. med. 51, 240–250 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9847-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9847-z