Abstract

Background

One in 25 Ugandan adolescents is HIV positive.

Purpose

The aim of this study is to examine the impact of an Internet-based HIV prevention program on Information-Motivation-Behavioral skills (IMB) Model-related constructs.

Methods

Three hundred and sixty-six sexually experienced and inexperienced students 13–18+ years old in Mbarara, Uganda, were randomly assigned to the five-lesson CyberSenga program or the treatment-as-usual control group. Half of the intervention participants were further randomized to a booster session. Assessments were collected at 3 and 6 months post-baseline.

Results

Participants’ HIV-related information improved over time at a greater rate for the intervention groups compared to the control group. Motivation for condom use changed to a greater degree over time for the intervention group—especially those in the intervention + booster group—compared to the control group. Behavioral skills for condom use, and motivation and behavioral skills for abstinence were statistically similar over time for both groups.

Conclusions

CyberSenga improves HIV preventive information and motivation to use condoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Sub-Saharan Africa remains the region most heavily affected by HIV, accounting for 68 % of the global population living with HIV and 72 % of global AIDS-related deaths in 2009 [1]. Current data suggest that HIV prevalence among Ugandan youth aged 15 to 19 years is 3 % [2] and that heterosexual sexual intercourse is responsible for 80 % of new HIV cases in Uganda [3]. Given the epidemiology of HIV transmission in Uganda, designing salient programs that focus on modifiable risk factors for heterosexual youth [3] and are based on strong theoretical models [4] has the potential to change the trajectory of new transmissions.

According to the Information-Motivation-Behavioral skills (IMB) Model of HIV preventive behavior, HIV preventive behavior is affected by one’s information about how to prevent HIV, one’s motivation to engage in non-risky behaviors, and one’s skills and abilities to enact these behaviors [5–7]. The influence of HIV preventive information and motivation on onset and sustainability of one’s preventive behavior is mediated by HIV preventive behavioral skills. Associations between these IMB constructs are generally well supported [5–13], including in samples of adolescents [14] and adults [15–17] in developing countries. Research has also shown that intervention programs guided by the IMB model have resulted in increases in HIV preventive behavior among adults [18] and adolescents [19] in developing settings. However, the influence that adolescent HIV prevention programs guided by the IMB model have on the information, motivation, and behavioral skills constructs across time is lacking in the literature. We found only one study that has examined IMB constructs among adolescents longitudinally [20]. A school-based, IMB-driven HIV prevention intervention was tested among 1577 minority high school students in an urban center in the USA. The different delivery modes were tested: classroom, peer, and classroom + peer. In general, statistically significant differences over time were most pronounced in the information construct for both sexually active and abstinent youth across all three arms [20]. How this translates to a developing country, where different social and cultural influences might be at play, is unknown.

In addition to creating salient programs that have a strong theoretical base, new and innovative methods are needed to affect behavior change and promote HIV risk reduction strategies among young people. The Internet is a promising mode of intervention delivery in developing settings, such as Uganda, because the costs associated with scaling up are minimal. Dissemination of online material is the same whether one person or 100,000 people use the program [21]. Just as importantly, it provides access to health information in a stigma-free, anonymous atmosphere [22], which is critical in settings such as Uganda, where being HIV positive is stigmatized and discussions about sex with adolescents are often assumed to cause subsequent sexual behavior [23, 24].

Data indicate that 45 % of adolescents in Mbarara, Uganda (a small municipality 4 h outside of Kampala), have used the Internet, 78 % of whom went online in the previous week [25]. Already, one third (35 %) have looked for information about HIV/AIDS on a computer or the Internet. Internet-delivered adolescent risk reduction interventions therefore appear to be both desired and feasible.

Anticipating ever-greater Internet access [25], an Internet-based HIV prevention and healthy sexuality education program called CyberSenga was developed and tested among secondary school students in Mbarara, Uganda. The program content was based upon the IMB model as well as data from extensive formative work [26–28]. The intervention focused on promoting HIV preventive behaviors using a harm reduction approach, meaning that abstinence was discussed alongside correct and consistent condom use. The content was developed to be culturally salient. For example, in Uganda, the Senga is the father’s sister. She is typically responsible for offering his female children advice and guidance, including about issues related to sexual health, as they come of age. The Kojja is the male equivalent. CyberSenga uses the Senga and Kojja figures to present salient, trustworthy role models for the youth to follow throughout the intervention. Moreover, as was noted in qualitative work with Ugandan youth, young people face multiple social, cultural, and economic factors that simultaneously “push” them toward (e.g., decline of the Senga, barriers to condom use) and “pull” them away (e.g., fear of pregnancy, loss of future) from risky sexual behavior [29]. These challenges were woven into the CyberSenga program content in the forms of vignettes and testimonials from young people.

Three hundred and sixty-six sexually experienced and inexperienced youth, 13 years of age and older, were randomly assigned to either the 5-week intervention or the treatment-as-usual control group. Half of the intervention group was further randomly assigned to a booster session. Follow-up data were collected at 3 and 6 months post-intervention end.

Behavioral outcomes have been reported elsewhere [30]. In brief, statistically significant results were not noted among the main outcomes. Past-3-month rates of abstinence and unprotected sex were similar for control and intervention participants at 6 months post-intervention end. Among the secondary outcomes, trends suggested that intervention participants were more likely than control participants to be abstinent (i.e., to not have sex) at 3 months post-intervention end (p = 0.08). Among youth who were abstinent at baseline, 88 % of intervention participants did not have sex during the 3-month follow-up period compared to 77 % of those in the control group (p = 0.02). Among youth who were sexually active at baseline, trends suggested that, at 6-month post-intervention end, youth in the intervention + booster group were three times more likely than those in the control group to have been abstinent during the past 3 months (i.e., in the time since the CyberSenga intervention; p = 0.15). Similarly, non-statistically significant but promising trends were noted for unprotected sex: compared to 24 % of youth in the intervention and 21 % in the control groups, 5 % of youth in the intervention + booster group reported unprotected sex in the past 3 months at 6-month post-intervention follow-up (p = 0.21).

To complement these behavioral outcomes, the aim of the current paper is to provide an assessment of the effect of the CyberSenga intervention on the IMB constructs over time among adolescents in a developing setting. Statistical models are estimated within the context of culturally specific factors that are implicated in sexual health decision-making. For example, maternal education attainment is consistently and strongly associated with child health indicators, including infant mortality rates and health-seeking behaviors [31, 32]. Both self-esteem and optimism about the future have been found to indirectly predict safer sex intentions among South African adolescents [33, 34]. In Kenya, research shows that caregiver social support may affect adolescent sexual activity and, perhaps, condom use [35].

Based upon previous research examining the impact of IMB-motivated prevention programs, we expect youth in the intervention to demonstrate increased information, motivation, and behavioral skills as they relate to HIV prevention behaviors from baseline to 6-month post-intervention follow-up compared to the control group. Because youth who are currently having sex are at greater risk for HIV, we posit that intervention content may be more personally relevant and immediately actionable, and thus, we expect greater increases in motivation and behavioral skills for sexually experienced versus abstinent youth among intervention participants. Finally, we anticipate that, among intervention participants, youth randomized to the booster session will demonstrate the greatest increases in all three domains.

Method

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Chesapeake Institutional Review Board in the USA and the Mbarara University of Science and Technology Ethical Committee in Mbarara, Uganda. Both committees approved the youth assent and adult permission process, including the assent/permission language. Permission forms were available to caregivers both in English and Runyankole, the local language in Mbarara. Written informed permission was obtained from the caregivers of day students and from the school principals, who are the legal caregiver proxies, for boarding students. Day students took the informed permission forms home to have them signed by their caregiver and returned the completed forms to the research assistants. Informed written assent was obtained from all youth participants. The clinical trial number is NCT00906178.

Setting

CyberSenga was conducted in Mbarara, Uganda, the seventh largest urban center in Uganda [36]. The greater district is mostly rural. Mbarara district’s net secondary school enrollment rate in 2009 was higher than the national average, 35 versus 24 % [36].

Intervention Description

Inspired by the culturally appropriate, community-based intervention conducted by Muyinda and colleagues [37], the CyberSenga program used a virtual Senga or Kojja as a guide through the intervention. The Senga introduced each topical area and then narrated the program as the topic was further elucidated for female participants, and the Kojja for male participants. Module 1 focused on information and presented facts about HIV (e.g., how HIV is and is not contracted, ways to reduce HIV risks, the prevalence rate of HIV in Uganda). Module 2 addressed aspects of motivation by focusing on problem-solving and communication skills (e.g., the steps to identifying and solving a problem, assertive versus aggressive or passive communication, non-verbal communication). Module 3 also addressed aspects of motivation, specifically motivations to have sex or, alternatively, to be abstinent (e.g., why youth choose to be abstinent or to have sex, benefits and drawbacks for having sex in adolescence). Module 4 presented behavioral skills, including condom use skills; and motivation, by supporting norms for consistent condom negotiation and use. Module 5 discussed culturally specific issues related to HIV preventive behavior, including coercive relationships between youth (e.g., physical or emotional dating abuse) as well as romantic relationships with adults (e.g., sugar daddies and sugar mommies). The booster module reviewed the information, motivation, and behavioral skills learned in the previous five modules.

Four different paths were created so that content could be tailored for adolescent men and women and those who were sexually active versus abstinent. The different versions presented similar content but with language to increase the personal relevance of the topic. For example, module 4 for abstinent youth acknowledged that while youth were not currently having sex, in the future, they may be ready to have sex in a healthy relationship and need to know how to use condoms. As another example, vignettes in module 2 for abstinent youth talked about how to delay having sex, whereas for sexually active youth, the vignettes discussed condom negotiation and choosing to not have sex when “not in the mood.” For adolescent women, content also explained that while condoms are often seen as the “man’s job,” both partners need to know how to use condoms correctly to ensure both partners’ health.

Participants

Partner schools were purposefully recruited to enroll a diverse group of adolescents. Two were all-boys Protestant schools, one was a mixed-sex Muslim school, and the fourth was a mixed-sex public school. Eligibility criteria for youth participants included the following: attendance at a partner school, enrollment in grades secondary 2 through 4 (approximately grades 9–11 in the USA), use of a computer and/or the Internet at least once in the past year (to promote a basic level of computer knowledge for this pilot study), guardian permission, and youth assent.

Participants were randomly recruited in coordination with school staff and oversight from the principal investigator. Because of time constraints due to the schools’ schedules, a subsample of students completed a brief screener to identify youth who met eligibility criteria for the RCT. All youth who were eligible were invited to participate.

Of the 740 adolescents who completed screeners, 366 (49 %) were eligible and randomized. Of the 374 adolescents who were not randomized, 324 were ineligible (i.e., had not used a computer or the Internet), 39 declined to assent or consent, 9 changed schools or were otherwise unavailable, and 2 assented but stopped participation before they completed the baseline survey and could be randomized. Thus, of those eligible, 88 % were randomized.

Youth were 16.1 years old on average (SD 1.4 years, range 13–18+ years). Although about half of secondary school students in Uganda are female [36], our sample was skewed toward males (84 %) in part because two of the partner schools were all boys. A little less than half (48 %) of participants’ mothers had advanced level of education or equivalent, as did one half (54 %) of participants’ fathers. Thirty-one percent of participants had ever had vaginal sex prior to baseline. The intervention and control arms were well balanced on almost all youth characteristics; boarding versus day scholars and family social support were exceptions.

Procedures

The CyberSenga survey and the online intervention were written in English. This is the official language of Uganda but is the non-primary language of all students [38]. Because Uganda has over 30 primary languages across tribes, it was not feasible to deliver one program for all youth in their first language. Nonetheless, English is the language of instruction and exams in schools.

Temporary “study cafés” were created in a designated room at each of the schools for the purposes of data collection and to provide participants in the intervention access to the CyberSenga program. Each student was assigned a netbook (i.e., mini laptop) to use. Internet access was provided with a router powered by a car battery.

Participants were randomized by the software program after they had completed the baseline survey in March, 2011. The arms were balanced on youth biological sex and previous sexual experience. Those assigned to the intervention were exposed to one of the four paths based upon their biological sex (adolescent men versus women) and sexual experience (sexually active versus abstinent) based upon their answers in the baseline survey. To be consistent with local norms and recommendations from the Community Advisory Board, “abstinence” included youth who had had sex more than 2 years ago. The control group (i.e., treatment-as-usual) received the sexual health education already offered at their schools. This programming varied by school but could have included brief informational programs delivered by The AIDS Support Organization (TASO) that often involved condom demonstrations, abstinence-only presentations from local church groups, etc.

After the baseline survey, research assistants (RAs) contacted participants who were randomly assigned to the CyberSenga intervention group and scheduled them to return to the program’s study café to complete the 5-module CyberSenga program. Participants were assigned to complete modules the same day of each week (e.g., Mondays) over the following 5 weeks. RAs provided appointment reminder cards and actively sought out participants who did not show up for their scheduled sessions so that they could complete the module the same day or reschedule for the next day. During sessions, RAs directed participants to a computer and helped them log in to the CyberSenga system as needed. Each module was approximately 45 min in length. Participants’ exposure to the CyberSenga program modules was endeavored to be as close to the desired program timeline (i.e., one module per week) as possible, but participants were allowed to complete more than one module per sitting if necessary.

Three months after baseline, in June 2011, the RAs contacted all participants and scheduled them to complete the follow-up survey, which participants completed online at the temporary study cafés. Data collection groups were separated so that control and intervention participants would not be completing the assessment in the same room with each other. RAs were present during data collection to assist participants.

Half of the intervention group was randomized to receive the booster session, which was delivered 1 month after the 3-month follow-up survey. Immediately prior to the scheduled exposure to the booster module, the RAs received a list of the participants who had been assigned to the booster from a password-protected Internet website and scheduled a time for them to return to the study cafés to complete the module.

Six months after baseline, in September 2011, the RAs contacted all participants and scheduled them to complete the second post-baseline survey. Procedures matched those implemented at 3 months post-baseline. Participants were given a completion certificate at the end of the 6-month follow-up as a nominal incentive to take part in the study.

As has been reported previously [39], 95 % (n = 173) of intervention participants completed all five modules. A similar percentage of youth (95 %, n = 86) randomized to the booster completed it. Ninety-six percent of intervention and 93 % of control participants provided 3-month follow-up data (χ 2(1) = 1.4, p = 0.24). Ninety-two percent of intervention and 93 % of control participants provided 6-month follow-up data (χ 2(1) = 0.4, p = 0.55).

Measures

The survey was pilot tested among the target population prior to the RCT in a beta test of 40 youth, as well as an informal read-through by younger youth who were “friends and family” of the staff to ensure comprehension.

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures were improvements in constructs of the IMB model over the 6-month post-intervention period. All outcome measures were either taken directly from or based upon those in the Teen Health Survey, which was designed specifically to measure key constructs of the IMB model by Fisher and Fisher’s team [40].

HIV prevention-related information was measured at each time point with six items. Three of these items (one with a slight modification) were used in the Teen Health Survey (e.g., “You can safely store condoms in your wallet for at least two months” with response options: definitely false to definitely true). The other three items were written to assess knowledge of information commonly misconstrued in the target population and were from the Uganda Demographic Health Survey [41] (e.g., “The HIV virus is small enough to go through a condom” with response options: definitely false to definitely true). An information score was created to reflect the percent of correct answers across the six items, with higher scores reflecting more knowledge of HIV-related information.

Three constructs of HIV prevention-related motivation were measured at each time point: (1) attitudes, (2) subjective norms, and (3) behavioral intentions. Within each aspect, two types were measured: abstinence and condom use.

HIV prevention-related attitudes toward abstinence were measured with one item (i.e., “For me, not playing sex until I’m an adult would be…” with response options: very bad to very good), and attitudes toward condom use were measured with four items (e.g., “If I play sex during the next two months, using condoms every time would be…” with response options: very bad to very good). A composite variable was created for the multi-item subscale by averaging responses across all four items (Cronbach’s alpha: baseline = 0.68, 3 months post-baseline = 0.92, 6 months post-baseline = 0.95). Higher numbers reflect more positive attitudes.

HIV prevention-related subjective norms for abstinence were measured with two items (e.g., “My boyfriend or girlfriend thinks we should not play sex until we’re both adults” with response options: very untrue to very true), and subjective norms for condom use were measured with eight items (e.g., “My friends would advise me to buy condoms or get them for free, during the next two months” with response options: very untrue to very true). A composite variable was created for both multi-item subscales by averaging responses across all subscale items (Cronbach’s alpha for subjective norms for abstinence: baseline = 0.66, 3 months post-baseline = 0.94, 6 months post-baseline = 0.96; Cronbach’s alpha for subjective norms for condom use: baseline = 0.85, 3 months post-baseline = 0.97, 6 months post-baseline = 0.98). Higher numbers reflect stronger subjective norms.

Behavioral intentions to be abstinent were measured with one item (i.e., “I’m planning not to play sex until I’m an adult” with response options: very untrue to very true), and behavioral intentions to use condoms were measured with four items (e.g., “During the next two months, I’m planning to buy condoms or get them for free” with response options: very untrue to very true). A composite variable was created for the multi-item subscale by averaging responses across all four items (Cronbach’s alpha: baseline = 0.70, 3 months post-baseline = 0.92, 6 months post-baseline = 0.94). Higher numbers reflect stronger intentions.

Behavioral skills for abstinence were measured with one item (i.e., “How hard or easy would it be for you to make sure you do not play sex until you an adult?” with response options: very hard to very easy), and behavioral skills for using condoms were measured with five items (e.g., “If you play sex, how hard or easy would it be for you to make sure you and your partner use a condom every time?” with response options: very hard to very easy). A composite variable was created for the multi-item subscale by averaging responses across all five items (Cronbach’s alpha: baseline = 0.63, 3 months post-baseline = 0.94, 6 months post-baseline = 0.97). Larger scores reflect stronger behavioral skills.

Other Potentially Influential Factors

At baseline, participants reported their age, sex, grade level, whether they were boarding or day students, paternal education, and maternal education. A substantial portion of participants reported being unsure of their parents’ education levels (paternal = 8.2 %; maternal = 14.5 %). Consequently, rather than impute these values, education levels were coded into two variables reflecting high paternal education (advanced level or equivalent, tertiary institution, or university graduate) versus all others.

At baseline, youth were asked how likely it was they thought their future would be bright, with responses coded to compare those who reported “likely” or “very likely” versus those who reported a lower likelihood. Social support was also measured at baseline using four items from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [42]. Each item included a statement related to the availability of social support from family. Participants responded using a 7-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7), where larger values reflect greater support. Scores on the four items were summed to create the familial social support variable scores (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.63), which were then dichotomized to reflect those who reported total family support 1 standard deviation above the mean versus all others. Physical health was assessed at each time point with one item that asked how participants would rate their physical health. Responses were coded to compare those who reported good or excellent health with those who reported poor or fair health [43]. Respect for self was also assessed at each time point with one item from the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale [44] that asked participants’ level of agreement with the statement: “I wish I could have more respect for myself.” Responses were coded such that those who reported low respect (somewhat or strongly agree) were compared to all others.

Three sex- and HIV/AIDS-specific potentially influencing factors were examined at baseline: whether participants had ever had vaginal sex (yes/no), whether they were tired of hearing about STD and HIV/AIDS prevention (strongly or somewhat agree versus all others), and one’s perceived chances of getting HIV/AIDS (no chance versus all others).

All of these other potentially influential factors were dichotomized for two reasons: to reduce collinearity in statistical analyses and also to be consistent with the way these variables have been coded in other studies [e.g., 30].

Statistical Analyses

Unless otherwise specified, missing and non-responsive (i.e., don’t know) data were imputed using best-set regression single imputation [45], which imputes data based on the best available subset of specified predictors [46]. Growth curve analyses were conducted using multilevel modeling with observations across time nested within person. Thus, observation is the lower level and person is the upper level. All variables that did not have a meaningful 0 value were grand-mean centered in all analyses. For each IMB outcome variable, a saturated model and a final parsimonious model were estimated. The saturated model included the main predictors (i.e., predictors specified in the IMB model, experimental condition, time, and the condition by time interaction term). To test alternative explanations for differences between the control and experimental groups, the saturated model included the other potentially influential variables assessed at baseline (e.g., age and perceived chance of getting HIV/AIDS) and over time (e.g., respect for self, and health). The saturated model additionally included terms for interaction effects of other factors that were expected to influence the CyberSenga program’s impact on the IMB components over time (i.e., the extent to which these components change in response to the CyberSenga program). For example, we expected a time by experimental condition by prior vaginal sex at baseline interaction, such that CyberSenga would have an effect on the IMB components, and that this effect would be different for sexually abstinent youth than for those who had engaged in vaginal sex because of the influence that prior behavior could have on sex-related information, motivation, and behavioral skills.

The parsimonious models included the main predictors (i.e., predictors specified in the IMB model, experimental condition, time, and the condition by time interaction term) regardless of statistical significance, and other potentially influential variables and terms for expected interaction effects that were determined in the estimate of the saturated model to be statistically significant at p ≤ 0.10. In addition, simpler effects (e.g., main effects) of other potentially influential variables included in statistically significant interaction terms were also retained in the parsimonious models regardless of statistical significance. For example, if the time by female biological sex interaction effect was statistically significant, then the female biological sex main effect was retained in the parsimonious model even if the main effect for female biological sex was not statistically significant. Results of the parsimonious models are reported.

Results

Table 1 presents results of parsimonious multilevel growth curve models that predict baseline status in individual constructs of the IMB model. Table 2 presents results of parsimonious multilevel growth curve models predicting individual constructs of the IMB model over time.

HIV Prevention-Related Information

Participants’ HIV prevention-related information changed over time differently depending on experimental condition (t(360) = 3.99, p < 0.001, = 2.63; Table 2). All three groups had the same amount of HIV prevention-related information at baseline (M predicted = 73.4 %). However, at 6 months post-baseline, the control group answered a similar percentage of HIV prevention-related questions correctly (M predicted = 72.4 %), whereas the intervention-only group answered a greater percentage correctly (M predicted = 77.6 %), and the intervention + booster group answered the greatest percentage correctly (M predicted = 82.8 %).

HIV Prevention-Related Motivation

Attitudes

HIV prevention-related attitudes toward abstinence did not change over time by experimental condition (Table 2). In contrast, attitudes toward condom use did (t(1087) = 2.79, p = 0.006, B = 0.12; Table 2). Overall, attitudes toward condom use became more positive over time (t(1057) = 5.13, p < 0.001, B = 0.28), but this change depended on experimental condition. At 6 months post-baseline, the intervention + booster group had the most positive attitudes (M predicted = 4.4), followed by the intervention-only group (M predicted = 4.1) and the control group (M predicted = 3.8).

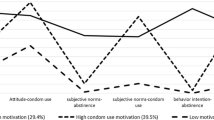

A three-way interaction of time by experimental condition by ever having had vaginal sex at baseline was noted (t(1087) = −2.58, p = 0.010, B = −0.17; see Table 2 and Fig. 1). At baseline, abstinent youth had less positive attitudes toward condom use (range of M predicted across experimental conditions = 3.3–3.4) than those who had ever had vaginal sex (range of M predicted across experimental conditions = 3.7–3.8). Over time, improvement in condom use attitudes was greater for those who were abstinent at baseline (range of change over time in M predicted across experimental conditions = 0.4–0.9) compared to those who had had vaginal sex at baseline (range of change over time in M predicted across experimental conditions = 0.2–0.7). Change was greatest for the intervention + booster group (range of change over time in M predicted across the sexually abstinent and sexually active at baseline groups = 0.7–0.9), followed by the intervention-only group (range of change over time in M predicted across the sexually abstinent and sexually active at baseline groups = 0.4–0.7) and then the control group (range of change over time in M predicted across the sexually abstinent and sexually active at baseline groups = 0.2–0.4). In addition, at 6 months post-baseline, the attitudes toward condom use of those in the intervention + booster group who were abstinent at baseline (M predicted = 4.3) were similarly positive to the attitudes of those in the intervention-only group who had had vaginal sex at baseline (M predicted = 4.2), and the attitudes toward condom use of those in the intervention-only group who were abstinent at baseline (M predicted = 4.0) were similarly positive to the attitudes of those in the control group who had had vaginal sex at baseline (M predicted = 3.9).

Subjective Norms

HIV prevention-related subjective norms toward abstinence did not change over time by experimental condition (Table 2). In contrast, subjective norms for condom use did (t(1085) = 2.44, p = 0.015, B = 0.12; Table 2). Overall, subjective norms for condom use became more positive over time (t(1085) = 2.88, p = 0.004, B = 0.19), but this change depended on experimental group. At baseline, the experimental groups were similar in subjective norms for condom use (range of M predicted across experimental conditions = 3.4–3.5). By 6 months post-baseline, the intervention + booster group had the most positive subjective norms (M predicted = 4.2), followed by the intervention-only group (M predicted = 4.0) and lastly the control group (M predicted = 3.8).

A three-way interaction effect of time by experimental condition by ever having had vaginal sex at baseline was noted (t(1085) = −3.62, p = 0.001, B = −0.25; see Table 2 and Fig. 2). At baseline, abstinent youth had less positive subjective norms for condom use (range of M predicted across experimental conditions = 3.3–3.4) than those who had had vaginal sex (range of M predicted across experimental conditions = 3.6–3.7). Over time, all youth’s subjective norms became more positive, but the improvement was greater for youth who had had vaginal sex at baseline (range of change over time in M predicted across experimental conditions = 0.3–0.8) compared to youth who were abstinent at baseline (range of change over time in M predicted across experimental conditions = 0.2–0.7). In addition, by 6 months post-baseline, subjective norms to use condoms for youth in the intervention + booster group who were abstinent at baseline (M predicted = 4.1) was equal to the average subjective norms for youth in the control group who had had vaginal sex at baseline (M predicted = 4.1).

Behavioral Intentions

Intentions to be abstinent did not change over time for any of the experimental groups (Table 2). However, intentions to use condoms changed over time differently by experimental group (t(1088) = 3.47, p = 0.001, B = 0.13). Overall, intentions to use condoms became stronger over time (t(1088) = 3.98, p < 0.001, B = 0.20), but this change depended on experimental group. At baseline, the experimental groups were similar in intentions to use condoms (M predicted = 3.4). By 6 months post-baseline, the intervention + booster group had the strongest intentions to use condoms (M predicted = 4.2), followed by the intervention-only group (M predicted = 4.0) and lastly the control group (M predicted = 3.7).

A three-way interaction effect of time by experimental group by having ever had vaginal sex at baseline was noted (t(1088) = −2.99, p = 0.003, B = −0.19). This interaction effect was similar to the interaction effect on attitudes toward condom use as shown in Fig. 1. At baseline, abstinent youth had weaker intentions to use condoms (M predicted = 3.2) than those who had had vaginal sex (M predicted = 3.7). Over time, all youth’s intentions to use condoms became more positive, although the improvement was greater for those who were abstinent at baseline (range of change over time in M predicted across experimental conditions = 0.4–0.9), compared to those who had had vaginal sex at baseline (range of change over time in M predicted across experimental conditions = 0.2–0.8). Change was greatest for the intervention + booster group (range of change over time in M predicted across the sexually abstinent and sexually active at baseline groups = 0.8–0.9), followed by the intervention-only group (range of change over time in M predicted across sexual abstinence at baseline group = 0.5–0.6) and finally by the control group (range of change over time in M predicted across the sexually abstinent and sexually active at baseline groups = 0.2–0.4). In addition, at 6 months post-baseline, the strength of the intentions to use condoms of those in the intervention + booster group who were abstinent at baseline (M predicted = 4.1) was similar to the strength of the intentions of those in the intervention-only group who had had vaginal sex at baseline (M predicted = 4.2), and the strength of the intentions to use condoms of those in the intervention-only group who were abstinent at baseline (M predicted = 3.8) was similar to the strength of the intentions of those in the control group who had had vaginal sex at baseline (M predicted = 3.9).

Behavioral Skills

Behavioral skills for abstinence did not differ over time by experimental condition (Table 2). In contrast, behavioral skills for condom use were affected by a three-way interaction effect of time by experimental condition by perceived chance of getting HIV/AIDS (t(1081) = 2.06, p = 0.039, B = 0.08; Table 2). Across all time points, youth who perceived no chance of getting HIV/AIDS had more skills for condom use than youth who perceived at least some chance (baseline M predicted = 3.1 and 3.0, respectively, and 6 months post-baseline M predicted = 3.2 and 3.0, respectively).

Discussion

In a sample of over 350 adolescents attending secondary school in rural Uganda, findings are supportive of a hypothesis that the Internet-based HIV prevention program CyberSenga may improve youths’ HIV preventive information as well as motivation as it relates to condom use. Findings further suggest that the booster, delivered 4 months after the initial intervention, may enhance the learning effect. Future healthy sexuality interventions for secondary school adolescents living in similar settings may consider titrating the exposure so that a review of the content is delivered at a later time period.

At the same time, motivation and behavioral skills for abstinence did not differ over time by experimental condition. This may be because abstinence is the culturally normative script for adolescents in Uganda [29], thus resulting in high scores in each of these domains at baseline. It may also be because our abstinence constructs were measured in almost all cases with one item, whereas our condom constructs were measured with multiple items. As such, the abstinence constructs were subject to less variability and opportunity to change over time. Behavioral skills for condom use also failed to improve over time. CyberSenga provided an explicit video showing the steps to put on a condom and suggested youth “practice” by watching the condom video multiple times. The program also provided locally specific places to purchase condoms. Subsequent encouragement to practice in real life the skills that youth were seeing on screen (e.g., go buy a condom and try putting it on a banana) was not provided however, due to cultural sensitivities. Future technology-based programs might consider suggesting youth practice these new skills in real life, ideally in ways that are culturally acceptable, to see if doing so invigorates behavioral skills acquisition.

The exceptionally high program completion and follow-up rates suggest that CyberSenga was of great interest to Ugandan adolescents. There is a paucity of culturally salient, anonymous, and accessible sexual health information that is created specifically for young people in Uganda, as well as many countries with high HIV prevalence rates. Ensuring that programs such as CyberSenga are easily accessible to both sexually experienced and inexperienced youth in a safe and non-stigmatizing manner needs to be a public health priority.

Several important nuances in the findings are noted. Perhaps most importantly, subjective norms for condom use improved over time particularly for intervention youth who were sexually active at the beginning of the program. Attitudes related to condoms and intentions to use condoms both increased notably for intervention youth who were abstinent at baseline. Findings for both sexually active and abstinent youth are noteworthy given the social undesirability to talk about condoms or to acknowledge adolescent sexual activity in Uganda. Results for sexually abstinent youth are especially encouraging because at the beginning of the study, these youth scored lower, on average, on all aspects of condom-related motivation compared to youth who had had sex in the past 2 years. At 6-month follow-up, not only had these constructs increased at a faster rate for abstinent youth in the intervention (particularly for those in the intervention + booster group); but in the case of attitudes toward and intentions to use condoms, they had increased to levels that were commensurate with those for sexually experienced youth in the intervention group (Fig. 1). Research suggests that one of the factors that most strongly predict current condom use is whether condoms were used at first sex [26, 47]. Ensuring that adolescents have positive attitudes toward condoms before they start having sex is critical. CyberSenga directly and consistently addressed the reasons why abstinent youth needed to know how to use and have a plan for obtaining condoms: That when they are older and in a healthy relationship, youth would likely be ready to have sex and would need to know how to put on a condom then. CyberSenga also acknowledged that youth might find themselves in a situation when unplanned sex “just happens.” It appears that this type of messaging was useful to help abstinent youth begin thinking concretely about condom use.

It is interesting that youth who had lower perceived risk of contracting HIV also had stronger skills for condom use. Perhaps these youth were able to correctly and consistently use condoms when they had sex and were, therefore, correctly appraising their HIV risk to be lower. It may also be an example of the “worried well.” Those who are at lowest risk for HIV are perhaps also those who attend more fully to HIV prevention messages. While the current data disallow strong interpretations about why this association was observed, it seems that a self-appraisal of high risk for HIV may be an important marker for targeted condom skills building.

Findings should be interpreted within study limitations. Results are based upon self-report. Sexual activity is an undesirable behavior for young people to acknowledge, especially in Uganda. Although great lengths were taken for content to be inclusive and non-stigmatizing, it is possible that, for example, sexually active youth in the intervention internalized shame that led to greater reports of abstinence and related beliefs over time. Indeed, across measures, the internal consistency of scales was higher at follow-up than at baseline, perhaps suggesting that social desirability bias increased over time for all youth. Additionally, the applicability of these findings to Ugandan youth outside of secondary school settings or to youth in other countries is unknown. It should also be noted that CyberSenga was designed to capitalize on the greater access and anonymity represented by the Internet. It is neither designed to nor will it reach all youth. With only one in four Ugandan youth enrolled in secondary schools [36], additional intervention efforts are needed to reach out-of-school youth, who may or may not have access to the Internet. Given the complexity of HIV preventive behavior, it is unlikely that a single intervention will affect HIV incident rates. Instead, an arsenal of prevention programs available through different modes and for different populations is needed.

Implications and Conclusions

In a developing community such as Mbarara, Uganda, that is struggling to curb the increase of HIV, particularly among young people, having an easily accessible and scalable program that affects important aspects of HIV preventive information, motivation, and behavioral skills has the potential to make a significant public health impact. Results suggest that CyberSenga may be one such program, with measurable improvements in HIV preventive information as well as motivation as it relates to condom use. Changes in attitudes and intentions to use condoms were especially pronounced for sexually inexperienced youth, suggesting that all youth, starting as young as 13 years of age, should be included in HIV prevention programs. Results further suggest that a booster session that is delivered some time later (e.g., 4 months hence) is more likely to affect behavior change than simply delivering all modules in succession. If this or similar programs were implemented in a school-based setting, it may be important to plan a review session (booster) that students complete in the subsequent school term.

As the Internet becomes more affordable and, therefore, more widely accessible in Africa, Internet-based programs such as CyberSenga have the potential to be disseminated widely to reach a greater number of young people. Future research could include a replication of CyberSenga in other settings that are less controlled, ideally both within Uganda as well as other eastern African countries. The intervention is publicly accessible at www.CyberSenga.com.

References

UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. Available at http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/documents/20101123_GlobalReport_full_en.pdf. Accessibility verified November 12, 2014.

Uganda Ministry of Health. Uganda AIDS Indicator Survey 2011. Available at http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/AIS10/AIS10.pdf. Accessibility verified November 12, 2014.

Uganda AIDS Commission. Global AIDS response progress report: Uganda. Available at http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2012countries/ce_UG_Narrative_Report%5B1%5D.pdf. Accessibility verified November 12, 2014.

Johnson WD, Diaz RM, Flanders WD, et al. Behavioral interventions to reduce risk for sexual transmission of HIV among men who have sex with men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008: CD001230.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Theoretical approaches to individual-level change in HIV risk behavior. In: Peterson JL, DiClemente RJ, eds. Handbook of HIV Prevention. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press; 2000: 3-55.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull. 1992; 111: 455-474.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, eds. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: Strategies for improving public health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002: 40-70.

Fisher CM. Adapting the information-motivation-behavioral skills model: Predicting HIV-related sexual risk among sexual minority youth. Health Educ Behav. 2012; 39: 290-302.

Bazargan M, Stein JA, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Hindman DW. Using the information-motivation behavioral model to predict sexual behavior among underserved minority youth. J Sch Health. 2010; 80: 287-295.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Williams SS, Malloy TE. Empirical tests of an information-motivation-behavioral skills model of AIDS-preventive behavior with gay men and heterosexual university students. Health Psychol. 1994; 13: 238-250.

Kalichman SC, Picciano JF, Roffman RA. Motivation to reduce HIV risk behaviors in the context of the Information, Motivation and Behavioral Skills (IMB) model of HIV prevention. J Health Psychol. 2008; 13: 680-689.

Walsh J, Senn T, Scott-Sheldon L, Vanable P, Carey M. Predicting condom use using the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) model: A multivariate latent growth curve analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2011; 42: 235-244.

Anderson ES, Wagstaff DA, Heckman TG, et al. Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model: Testing direct and mediated treatment effects on condom use among women in low-income housing. Ann Behav Med. 2006; 31: 70-79.

Maticka-Tyndale E, Tenkorang EY. A multi-level model of condom use among male and female upper primary school students in Nyanza, Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2010; 71: 616-625.

Bryan AD, Fisher JD, Benziger TJ. HIV prevention information, motivation, behavioral skills and behaviour among truck drivers in Chennai, India. AIDS. 2000; 14: 756-758.

Linn JG, Garnelo L, Husaini BA, Brown C, Benzaken AS, Stringfield YN. HIV prevention for indigenous people of the Amazon basin. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2001; 47: 1009-1015.

Yang X, Xia G, Li X, Latkin C, Celentano D. Social influence and individual risk factors of HIV unsafe sex among female entertainment workers in China. AIDS Educ Pre. 2010; 22: 69-86.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cain D, Jooste S, Skinner D, Cherry C. Generalizing a model of health behaviour change and AIDS stigma for use with sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2006; 18: 178-182.

Malow RM, Stein JA, McMahon RC, Dévieux JG, Rosenberg R, Jean-Gilles M. Effects of a culturally adapted HIV prevention intervention in Haitian youth. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009; 20: 110-121.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan AD, Misovich SJ. Information-motivation-behavioral skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychol. 2002; 21: 177-186.

Ybarra ML, Eaton WW. Internet-based mental health interventions. Ment Health Serv Res. 2005; 7: 75-87.

Monico SM, Tanga EO, Nuwagaba A, Aggleton P, Tyrer P. Uganda: HIV and AIDS-related discrimination, stigmatization, and denial. Available at http://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub02/jc590-uganda_en.pdf. Accessibility verified November 12, 2014.

Blum RW. Uganda AIDS prevention: A, B, C and politics. J Adolesc Health. 2004; 34: 428-432.

Kiapi-Iwa L, Hart GJ. The sexual and reproductive health of young people in Adjumani district, Uganda: Qualitative study of the role of formal, informal, and traditional health providers. AIDS Care. 2004; 16: 339-347.

Ybarra ML, Kiwanuka J, Emenyonu N, Bangsberg DR. Internet use among Ugandan adolescents: Implications for HIV intervention. PLoS Med. 2006; 3: e433.

Ybarra ML, Korchmaros J, Kiwanuka J, Bangsberg D, Bull S. Examining the applicability of the IMB model in predicting condom use among sexually active secondary school students in Mbarara, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2012; 17: 1116-1128.

Ybarra ML, Biringi R, Prescott T, Bull SS. Usability and navigability of an HIV/AIDS internet intervention for adolescents in a resource-limited setting. Comput Inform Nurs. 2012; 30: 587-595.

Bull S, Nabembezi D, Birungi R, Kiwanuka J, Ybarra ML. Cyber-Senga: Ugandan youth preferences for content in an internet-delivered comprehensive sexuality education programme. East Afr J Publ Health. 2010; 7: 58-63.

Katz IT, Ybarra ML, Wyatt MA, Kiwanuka JP, Bangsberg DR, Ware NC. Socio-cultural and economic antecedents of adolescent sexual decision-making and HIV-risk in rural Uganda. AIDS Care. 2013; 25: 258-264.

Ybarra ML, Bull SS, Prescott TL, Korchmaros JD, Bangsberg DR, Kiwanuka JP. Adolescent abstinence and unprotected sex in CyberSenga, an Internet-based HIV prevention program: Randomized clinical trial of efficacy. PLoS ONE. 2013; 8: e70083.

Smith LC, Ruel MT, Ndiaye A. Why is child malnutrition lower in urban than in rural areas? Evidence from 36 developing countries. Available at http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/fcndp176.pdf. Accessibility verified November 12, 2014.

Gakidou E, Cowling K, Lozano R, Murray C. Increased educational attainment and its effect on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: A systemic analysis. Lancet. 2010; 376: 959-974.

Bryan A, Aiken L, West S. HIV/STD risk among incarcerated adolescents: Optimism about the future and self-esteem as predictors of condom use self-efficacy. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004; 34: 912-936.

Bryan A, Kagee A, Broaddus M. Condom use among South African adolescents: Developing and testing theoretical models of intentions and behavior. AIDS Behav. 2006; 10: 387-397.

Puffer E, Meade C, Drabkin A, Broverman S, Ogwang-Odhiambo R, Sikkema K. Individual- and family-level psychosocial correlates of HIV risk behavior among youth in rural Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2010; 15: 1264-1274.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics. 2010 Statistical Abstract. Available at http://www.ubos.org/onlinefiles/uploads/ubos/pdf%20documents/2010StatAbstract.pdf. Accessibility verified November 12, 2014.

Muyinda H, Nakuya J, Whitworth JAG, Pool R. Community sex education among adolescents in rural Uganda: Utilizing indigenous institutions. AIDS Care. 2004; 16: 69-79.

Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook: Uganda. Available at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ug.html. Accessibility verified November 12, 2014.

Ybarra ML, Bull SS, Prescott TL, Birungi R. Acceptability and feasibility of CyberSenga: An Internet-based HIV-prevention program for adolescents in Mbarara, Uganda. AIDS Care. 2014; 26: 441-447.

Misovich SJ. The Teen Health Survey. Available at http://www.chip.uconn.edu/chipweb/documents/Research/M_IMBTeenHealthSurvey.pdf. Accessibility verified November 12, 2014.

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), ORC Macro: Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006. Calverton, MD: UBOS and Macro International Inc., 2007.

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988; 52: 30-41.

Ware JE, Kosinski M. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A Manual for Users of Version 1. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc.; 2001.

Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965.

StataCorp: Stata Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2009.

Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987.

Hendriksen ES, Pettifor A, Lee SJ, Coates T, Rees H. Predictors of condom use among young adults in South Africa: The reproductive health and HIV research unit national youth survey. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97: 1241-1248.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the entire CyberSenga Study team from Internet Solutions for Kids; Internet Solutions for Kids, Uganda; Mbarara University of Science and Technology; the University of Colorado; and Harvard University, who contributed to the planning and implementation of the study. Finally, we thank the schools and the students for their time and willingness to participate in this study.

Funding

The project described was supported by Award Number R01MH080662 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The clinic trial registration number is NCT00906178. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Authors Ybarra, Korchmaros, Prescott, and Birungi declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed youth assent and parent permission process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Ybarra, M.L., Korchmaros, J.D., Prescott, T.L. et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Increase HIV Preventive Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skills in Ugandan Adolescents. ann. behav. med. 49, 473–485 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9673-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9673-0