Abstract

Shame plays a central role in psychosocial functioning, being a transdiagnostic emotion associated with several mental health conditions. According to the evolutionary biopsychosocial model, shame is a painful and difficult emotion that may be categorized into two distinct focal components: external and internal shame. External shame is focused on the experience of the self as seen in a judgemental way by others, whereas internal shame is conceptualized as self-focused negative evaluations and feelings about the self. The current study aimed to develop the External and Internal Shame Scale (EISS) to assess in a single measure these two dimensions. The study was conducted in a community sample comprising 665 participants (18 to 61 years old). Three models were tested through confirmatory factor analysis. One higher order factor (global shame) with two lower order factors (external and internal shame) revealed a good fit to the data. The scale reliability and its association with other related constructs measures were also addressed. Additionally, gender differences on shame were explored. Results showed that EISS subscales and global score presented good internal consistency, concurrent validity and were associated with depressive symptoms. Regarding gender differences, results revealed that women presented significantly higher scores both in external and internal shame. The EISS showed to be a short, robust and reliable measure. The EISS allows the assessment of the specific dimensions of external and internal shame as well as a global sense of shame experience and may therefore be an important contribution for clinical work and research in human psychological functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Shame has been recognized as a universal human emotion that plays a critical role in psychosocial functioning and development, specifically in the formation of one’s sense of self and self-identity as a social agent, and in social and moral behaviour (Dearing and Tangney 2011; Gilbert 2007; Gilbert and Andrews 1998; Tracy and Robins 2004). An extensive body of research has documented the association between shame and mental health problems. In particular, shame has systematically been recognized as a transdiagnostic emotion associated with psychopathological conditions (Kim et al. 2011; Harman and Lee 2010; Pinto-Gouveia and Matos 2011; Troop et al. 2008).

Shame is generally considered as a particularly intense, and often incapacitating, unwanted emotion involving feelings of inferiority, defectiveness, powerlessness, uselessness, isolation and self-consciousness, along with a desire to escape, hide or conceal deficiencies (Gilbert 1997, 1998; Kaufman 1989; Tangney and Dearing 2002; Tangney et al. 1996). Indeed, shame has long been acknowledged as one of the most aversive self-conscious emotions (Gilbert 1998; Kaufman 1989; Tangney and Dearing 2002; Tracy et al. 2007) but it is also regarded as a socially-focused emotion, often triggered by threats to one’s social self and status (Gilbert 1998, 2007). Theorists argue that the experience of shame emerges from detrimental changes and losses in one’s social status, with being demeaned or diminished in the social arena. It is linked with feelings of being devalued, dishonoured, demoted, discredited, ridiculed, humiliated, ostracized and scorned (Gilbert 1997, 2007). Shame is also related to feelings of aloneness, alienation, isolation and disconnection from others (Gilbert 1998, 2007; Nathanson 1994; Tangney and Dearing 2002). However, the focus of what is shaming is very much constrained by one’s social norms and cultural values (Fessler 2007; Leeming and Boyle 2004).

External and Internal Shame

In light of the evolutionary biopsychosocial model, shame is an involuntary defensive response to the awareness that one’s social attractiveness is under threat or has been lost, alerting individuals to disruptions in their social rank and social relationships (Gilbert 1998, 2007). It is thought to have evolved as a damage limitation strategy to keep the self, safe from rejection, exclusion, attacks or disengagement from others, ensuring human’s (social) survival and welfare (Gilbert 2007). According to this model, shame may be categorized into two distinct focal components or dimensions (external and internal shame): one focused on the ‘experience of the self as seen and judged by others’ and the other focused on the ‘experience of the self as seen and judged by the self’, involving distinct attention, monitoring and processing systems (Gilbert 1998, 2007).

External shame relates to the experience of oneself as existing negatively in the minds of others, as having deficits, failures or flaws exposed (Gilbert 1998, 2002). One believes that others see the self as inferior, inadequate, worthless or bad; that others are looking down on the self with a contemptuous or condemning view and might (or already have) criticize, reject, exclude or even attack the self. One’s attention and cognitive processing are attuned outwardly, directed to what is going on in the mind of the other about the self. The behaviour is orientated towards trying to positively influence one’s image in the mind of other (e.g., by submitting, appeasing or displaying desirable qualities; Gilbert 1998, 2002, 2007).

In turn, internal shame is linked to the inner dynamics of the self and to how one judges oneself, being associated with global self-devaluations and feelings of inadequacy, inferiority, undesirability, emptiness, or isolation (Gilbert 2003). The attention and cognitive processing are directed inwardly to one’s emotions, personal attributes and behaviour, and focused on the self’s flaws and shortcomings (Gilbert 2002; Lewis 2000). According to Gilbert (2002, 2007), internal shame can be seen as an internalizing defensive response to external shame, where one may begin to identify with the mind of the other and engage in negative self-evaluations and feelings, seeing the self in the same way others have (as flawed, inferior, undesired and globally self-condemning). This defensive response aims at restoring one’s image and protect the self against rejection or attacks from others (Gilbert 1998, 2003; Gilbert and Irons 2009). Internal shame can be related to a process of internal shaming, linked to the painful internal experience of self-criticism and self-persecution (Gilbert 2007; Gilbert et al. 2004).

Even though external and internal shame are regarded as different dimensions of this emotional experience, there is a close link between them, they encompass the same core domains (Inferiority/Inadequacy, Exclusion, Emptiness, and Criticism) and they both are crucial for social functioning (e.g., Gilbert 2002). In fact, shame experiences often comprise both externally and internally focused shame, fuelling each other. The same is to say that, the hurt that derives from recognizing that one’s social attractiveness has diminished is likely to involve severe self-devaluations and self-blame. At the same time, the painful self-depreciation usually arises with the awareness that others share the same negative view of the self. Nonetheless, the dimension of shame that is most salient in a particular shame experience can vary, as does one’s proneness to experience one dimension more than the other (Kim et al. 2011; Gilbert 2002, 2007).

Consistent research has shown that external and internal shame are both associated with a range of psychological problems, such as depression (for a review see Kim et al. 2011), anxiety (Pinto-Gouveia and Matos 2011), paranoia and social anxiety (Matos et al. 2013), and eating disorders (Murray and Waller 2002; Troop et al. 2008).

Measurement of Shame

Given the growing empirical interest on this emotion, numerous instruments have been developed. However, the measurement of shame has faced some methodological problems. The difficulties are primarily related to the lack of consensus among authors regarding the definition of shame, and to the fact that directly assessing this affective experience is difficult (Andrews 1998; Harder 1995; Tangney 1996). Also, the nature of the topic is extremely sensitive, which increases the likelihood of social desirability bias (Rizvi 2010).

Nevertheless, there have been significant methodological advances on shame measurement (e.g., Andrews 1998; Cook 1996; Elison et al. 2006; Goss et al. 1994; Harder 1995; Harder et al. 1992; Matos et al. 2015; Schalkwijk et al. 2016; Tangney and Dearing 2002). In particular, two main self-report questionnaires have been widely used to assess external and internal shame. The Other As Shamer scale (OAS; Goss et al. 1994), a 18-item measure designed to assess external shame; and the Internalized Shame Scale (ISS; Cook 1994/ 2001), a 24-item questionnaire assessing internal shame. Several studies conducted in samples from different countries/languages have shown that these two self-report instruments are cross-culturally valid and reliable (Balsamo et al. 2015; Del Rosário and White 2006; Goss et al. 1994; Matos et al. 2012; Matos et al. 2015; Rybak and Brown 1996; Saggino et al. 2017). Also, the Compass of Shame Scale (CoSS) is a self-report measure widely validated and designed not to address feelings of shame but shame regulation styles, which encompasses internalizing and externalizing shame-coping styles (Elison et al. 2006; Schalkwijk et al. 2016). However, in the current literature, there is no measure that simultaneously allows the assessment of both external and internal shame feelings, as well as a global sense of shame. Furthermore, a measure comprising these two dimensions could be relevant, not only to advance research on shame, its association with psychological well-being, and its transdiagnostic nature, but also in terms of clinical work with clients presenting psychological difficulties where shame may play a crucial role.

Given the significance of external and internal shame to the understanding of human functioning and their critical role in the vulnerability and maintenance of mental health problems (Luoma et al. 2012; Gratz et al. 2010; Rüsch et al. 2007), in particular internalizing disorders such as depression (for a review, Kim et al. 2011; Balsamo et al. 2015; Matos et al. 2015), it is still important to continue to work on operationalizing these dimensions. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to develop a short and reliable measure that allows capturing both external and internal shame and to examine its factor structure and psychometric properties. Additionally, gender differences were explored given that previous studies have pointed to the existence of differences between male and female participants regarding self-conscious emotions, such as shame (Else-Quest et al. 2012).

Materials and Methods

Participants

The factor structure of the EISS was tested in a sample comprised of 665 Portuguese adults, 152 (22.9%) men and 513 (77.1%) women, collected from the general population with ages between 18 and 61 years old (M = 27.11; SD = 9.53), and a mean of 14.34 (SD = 2.35) years of education. Concerning marital status 510 (76.7%) participants were single, 132 (19.8%) were married and 23 (3.5%) were divorced. A sub-sample of 190 participants was used to explore associations between EISS and other related measures.

Procedures

The current study is part of a wider research investigating the transcultural nature of shame. All ethical requirements were followed and the research protocol was approved by the University of Queensland School of Psychology Ethics Committee with the approval number 18-PSYCH-4-77-JMC. Participants were collected through online advertisement, using social network and private messages, and were asked to share it with two more friends (Exponential Non-Discriminative Snowball Sampling method). The online advertisement included detailed information about study’s procedure and aims, the voluntary nature of the participation, and an Internet link, redirecting potential participants to an online research protocol. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Participants were asked to complete a brief socio-demographic questionnaire and the Portuguese validated versions of the self-report instruments described below.

Scale Development

The External and Internal Shame Scale (EISS) was developed according to the steps recommended by relevant literature (e.g., Boateng et al. 2018; DeVellis 2012; Kline 2000), to assess trait shame in a single measure that evaluates the propensity to experience external and internal shame. First, based on literature review (Gilbert and Andrews 1998; Kaufman 1989; Lewis 2000; Tangney and Dearing 2002), the authors identified four core domains of the experience of shame that are clinically relevant and present both in external and internal shame: 1) inferiority/inadequacy; 2) sense of isolation/exclusion; 3) uselessness/emptiness; 4) criticism/judgment. Then four items were generated to assess each of these four domains, a pair for an external shame dimension (ES-EISS; e.g., “Other people see me as not being up to their standards”) and another pair for an internal shame dimension (IS-EISS; e.g., “I am different and inferior to others”). This process resulted in a pool of 16 items (Table 1). This preliminary version of the scale was administered to a group of 20 undergraduate students, preceded by the following instructions: “Below are a series of statements about feelings people may usually have, but that might be experienced by each person in a different way. Please read each statement carefully and circle the number that best indicates how often you feel what is described in each item”. Participants are asked to rate each item using a 5-point scale (0 = “Never” to 4 = “Always”). These participants were asked to complete the scale and comment on whether the items reflected their shame-related experiences. The items were further subject to discussion and revision. In a next step, a group of researchers and clinical psychologists with expertise on the evolutionary biopsychosocial model of shame (Gilbert 1998, 2007) were asked to select one item of each pair of items, justifying why they considered that it better captured the content of each of the four domains. Based on these experts’ reports, a final version of 8 items was obtained, 4 items assessing external shame and 4 items assessing internal shame.

Measures

Participants completed the EISS and the Portuguese versions of the following measures:

The Others As Shamer-2 (OAS-2; Matos et al. 2015)

The OAS-2 is a short version of the OAS (Goss et al. 1994) developed based on expert ratings. It encompasses 8 items intended to measure external shame (global judgements of how people think others view them). Respondents are asked to rate on a 5-point scale (0–4) the frequency of their feelings and experiences in items such as “People distance themselves from me when I make mistakes”. Higher scores reveal high external shame. The OAS-2 showed a unidimensional structure, good internal consistency (α = .82) and good concurrent and divergent validities. In the current sample a Cronbach alpha of .94 was found.

Forms of Self-Criticizing & Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS; Gilbert et al. 2004)

The FSCRS is a scale assessing the way people think and react in face of failures or setbacks. Two forms of self-criticism are included: (1) inadequate-self, (e.g., “There is a part of me that feels I am not good enough”), and (2) hated-self (e.g., “I have a sense of disgust with myself”). The FSCRS also measures the ability to self-reassure (e.g., “I am gentle and supportive with myself”). Participants were asked to answer the 22 items following the statement “When things go wrong for me...”, selecting in 5-point scale (0 = “Not at all like me” to 4 = “Extremely like me”) the extent to which each item applies to their experience. The Cronbach’s alphas were .90 for inadequate self, and .86 for hated self and self-reassurance subscales (Gilbert et al. 2004). The Portuguese version also reported good internal consistency (.62 > α > .89; Castilho et al. 2014). In this study, the self-criticism dimension was used as a measure of the process of internal shaming (Gilbert 2007; Gilbert et al. 2004), and it was calculated by summing the inadequate-self and hated-self subscales (SC-FSCRS; Halamová et al. 2018), and presented a Cronbach alpha of .90. The self-reassurance dimension showed a Cronbach alpha of .88.

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21; Lovibond and Lovibond 1995)

The DASS-21 comprises three subscales assessing depression (7 items), anxiety (7 items), and stress (7 items) symptoms. Items are answered in a 4-point scale ranging from 0 = Never to 3 = Always. In the Portuguese version, a good internal consistency was obtained for the depression scale (α = .85; Pais-Ribeiro et al. 2004). In the current study only the depression subscale was used and a Cronbach alpha of.88 was found.

Data Analysis

Because the EISS development was theoretically-driven, that is, the relationships between the observed and the unobserved variables were previously hypothesized, the EISS factor structure was examined through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), using the Maximum likelihood method, through AMOS software (v.21, Chicago, IL, USA). Three models were identified: Model 1 was an orthogonal two-factor model; Model 2 was an alternative hierarchical two factor model where the two dimensions of external and internal shame were correlated; finally, Model 3 was represented by one higher order factor (global shame) with two lower order factors (external and internal shame). The second order structure hypothesized in Model 3 should only be tested if there is evidence that the two lower order factors are correlated (Byrne 2010).

Model fit was ascertained using the chi-square statistic and five goodness of fit indicators: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), the Tucker and Lewis Index (TLI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% confidence interval (CI), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR; Browne and Cudeck 1993). The CFI is a comparative index that compares the fit of the proposed model with the fit of a baseline model. The GFI indicates the extent to which observed data matches the theory driven values. The TLI is a relative incremental fit index. CFI, GFI and TLI values are indicative of a good fit when ranging from .90 to .95 and a very good fit when values are above .95 (Hu and Bentler 1999). The RMSEA with a 90% confidence interval is indicative of acceptable when values are inferior to .10 (Hair et al. 2010). The SRMR, defined as the standardized difference between the observed correlation and the predicted correlation, points to good fit when values are below .08 (Hu and Bentler 1998). Reliability of the EISS was examined by calculating the Cronbach alphas for each subscale and global score.

Construct validity was estimated calculating the correlation of the EISS subscales with other measures tapping the same construct (concurrent validity) and measures of related concepts (concurrent validity). Discriminant validity was tested through correlations between the EISS global score, IS and ES subscales and the self-reassurance subscale of the FSCRS. Furthermore, the inter-correlation between the two EISS subscales was calculated through Pearson correlation. Finally, t-tests for independent samples were used to test gender differences on the EISS global score and subscales.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

An orthogonal two factor model (Model 1) was tested and showed a poor fit to the data: χ2(20) = 672.99; p < .001, CFI = .73; GFI = .85; TLI = .62; RMSEA = .22 [90% CI .21–.24; p < .001] and SRMR = .33. A hierarchical model with two factors (Model 2) was estimated. Model 2 revealed a good fit to the data, with χ2(19) = 126.73; p < .001; CFI = .96; GFI = .95; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .09 [90% CI .08–.11; p < .001]; SRMR = .04. Given that external and internal shame factors present a moderate intercorrelation (r = .47; p < .110), the one higher order factor with two lower order factors (Model 3) was tested (Fig. 1). Results revealed that Model 3 presented similar adequate global fit indexes, χ2(19) = 126.73; p < .001; CFI = .96; GFI = .95; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .09 [90% CI .08–.11; p < .001]; SRMR = .04, to Model 2. This higher order model was therefore chosen as the most adequate to represent the theoretical model and was in accordance with the aim of developing a measure that would allow, not only the assessment of external and internal shame, but also of a global sense of the shame experience. Local adjustment indicators analysis confirmed the adequacy of Model 3 with all items revealing adequate standardised regression weights, which varied from .64 (item 5) to .81 (item 4) (Fig. 1). Thus, all values were above the recommended cut-off point of .40 (Tabachnick and Fidell 2007). Squared multiple correlations results also confirmed the EISS reliability, with all items showing values ranging from .41 (item 5) to .74 (item 4).

Reliability

Regarding reliability (Table 2), Cronbach’ alphas of .80 and .82 were found for the external shame subscale and for the internal shame subscale, respectively. The EISS total scale revealed a Cronbach alpha of .89. Additionally, the elimination of any item would not increase the scale reliability, suggesting that all items are relevant in assessing ES and IS. Item-total correlations were all moderate to high, ranging from .55 to .75. EISS items’ skewness values varied between 0.07 (items 2 and 8) and 2.21 (item 7), and kurtosis values ranged from 0.05 (item 6) to 4.93 (item 7), indicating a non-severe violation of normal distribution (Kline 2005).

EISS Relation with Other Measures

Concurrent validity was assessed by calculating the zero-order and partial correlation coefficients between each of the two EISS subscales and other measures tapping the same constructs. The OAS-2 was used as a measure of ES and the self-criticism subscale of the FSCRS was used as a measure of IS. Table 3 presents results of the zero-order and partial correlations.

Medium to high associations were found between the EISS subscales and the OAS-2 and the SC-FSCRS. The analysis of the zero order correlations showed that all subscales were strongly associated. However, partial correlations showed a different pattern of associations. The association between ES and the OAS-2 was strong and significant, even when controlling for the influence of IS. On the contrary, when excluding the influence of ES, the association between IS and OAS-2 becomes small and near non significance (r = .15; p = .050). A similar pattern was found regarding the association between the IS subscale and the SC-FSCRS. Results on the partial correlation between the IS and the SC-FSCRS while controlling for the ES were strong and highly significant (r = .56; p < .001); on the contrary, the association between ES and the SC-FSCRS subscale when controlling the IS becomes weak and non-significant (r = .01; p = .950).

The association between EISS global score, the ES and IS subscales and the SR-FSCRS (self-reassurance) was calculated to address discriminant validity. Results showed that ES was inversely and moderately correlated with self-reassurance, and IS and global shame were negatively and strongly linked to the ability to self-reassure. Partial correlations between the IS and the SR-FSCRS while controlling for the ES were moderate and highly significant (r = −.45; p < .001); on the contrary, when controlling the IS the association between ES and the SR-FSCRS subscale becomes weak and on the threshold of significance (r = .15; p = .044).

Concurrent validity was assessed by testing the associations between EISS global score and its subscales and the DASS-21 Depression subscale. The depression score was strongly correlated with the EISS global score and both subscales. When testing the partial correlations for each subscale, the partial correlations remained significant but smaller than the zero-order correlations. Moreover, the ES and IS subscales showed to be positively and significantly correlated (r = .76; p < .001).

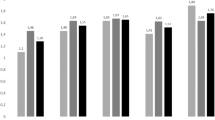

Gender Differences on Shame as Measured by the EISS

Significant differences were found when comparing men’s (m) and women’s (w) mean scores on the EISS global scale [Mm = 7.99(4.68) vs. Mw = 10.57(5.71), t(663) = −5.10; p < .001, d = 0.49], on the External shame subscale [Mm = 4.90(2.60) vs. Mw = 5.88(2.85), t(663) = −3.77; p < .001, d = 0.36] and on the Internal Shame subscale [Mm = 3.09(2.48) vs. Mw = 4.70(3.21), t(663) = −5.70; p < .001, d = 0.56], with women presenting higher scores.

Discussion

A substantial body of literature has demonstrated that external shame and internal shame are key transdiagnostic emotional experiences, central to the understanding of human functioning, and showing a significant association with a range of mental health difficulties (Gilbert 2007; Kim et al. 2011; Tangney and Dearing 2002). Despite recent advances in shame measurement, to our knowledge there is no measure that assesses both external (ES) and internal shame (IS) as conceptualised by the evolutionary biopsychosocial model. Furthermore, the relevance of using brief and reliable self-report measures to operationalize psychological constructs has been emphasized (DeVellis 2012). Therefore, the current study sought out to develop a short and reliable self-report instrument that captures both ES and IS: the External and Internal Shame Scale (EISS), as well as a global sense of shame.

The EISS items were designed to assess external and internal shame considering four core domains (Inferiority/Inadequacy, Exclusion, Emptiness and Criticism), based on theoretical literature and clinical experience. Results showed that the selected 8 items were relevant to measure ES and IS and presented good psychometric properties.

The EISS factor structure was tested through CFA, where three models were compared: an orthogonal two-factor model, a two-factor model hypothesizing the intercorrelation between the ES and IS factors, and one higher order factor (global sense of shame) with two lower factors (ES and IS) model. The first model presented a poor fit to the data and, even though the second model revealed an acceptable fit, the higher order model showed a good fit and it was the one that best represented the theoretical framework and the objective underlying the designing of the EISS. These findings are in line with the literature review and the evolutionary biopsychosocial model of shame that inspired the EISS development (Gilbert 2002, 2007). Concerning reliability, the item-total correlations further confirmed the adequacy of the items. In addition, the two shame dimensions and the global shame score presented good internal consistencies, similar to that found for other external and internal shame measures (e.g., Cook 1994; Goss et al. 1994; Matos et al. 2015; Matos et al. 2012).

Concurrent validity results further corroborated our hypothesis by showing that the global EISS score and the two dimensions have strong correlations with measures that assess similar constructs. Also, the EISS external shame dimension revealed a stronger association with the widely used external shame measure (OAS-2) whereas the EISS internal shame dimension exhibited a stronger correlation with a measure of internal shame (as assessed by SC-FSCRS). Of note, partial correlation analysis supported the specificity of EISS two dimensions indicating that when controlling for the effect of EISS internal shame dimension, the correlation between the EISS external shame and OAS-2 remained strong while its association with SC-FSCRS was no longer significant. Similarly, when controlling for the effect of EISS external shame dimension, the correlation between EISS internal shame and SC-FSCRS was still strong but the magnitude of its association with OAS-2 decreased from strong to weak. These results clearly support the concurrent validity of the two EISS dimensions. Findings corroborated the discriminant validity of the EISS showing that global shame and the external and internal shame dimensions were negatively associated with the ability to self-sooth and self-reassure. Interestingly, when internal shame was controlled for, the link between external shame and self-reassurance weakens and loses significance, suggesting that internal shame seems to be key in the interplay between shame and one’s ability to self-reassure when facing hardships. Concurrent validity showed that EISS global score and its dimensions were strongly correlated with depressive symptoms.

Regarding gender differences, women presented higher levels of external and internal shame than men, as measured by the EISS. These results are in line with previous evidence suggesting that, throughout different developmental stages, females tend to report higher shame than males (see Else-Quest et al. 2012 for a meta-analysis).

These findings may be seen as a relevant contribution to shame measurement by confirming the adequacy of the new developed EISS and its external and internal dimensions, which proved to be an economic, valid and reliable measure to assess external and internal shame, as well as global sense of shame.

Nevertheless, some methodological limitations should be taken into account when interpreting these results. First, even though the EISS was developed base on a solid theoretical background, since shame is a multidimensional construct, other content areas besides the four core domains assessed (Inferiority/Inadequacy, Exclusion, Emptiness and Criticism) may be relevant to consider. Though, the concurrent validity results seem to indicate that the EISS captures the nature of ES and IS. Secondly, this study was conducted in a general population sample and therefore the generalization of findings to a clinical population is limited. Future research should therefore seek to replicate these findings using clinical samples. In terms of gender differences, it is important to note that the EISS items, by tapping into global, nonspecific assessments of the self may be reflecting self-stereotyping and gender role assimilative effects (Else-Quest et al. 2012; Ferguson and Eyre 2000). Therefore, future research should further explore these gender differences in larger samples from different cultural backgrounds, and examine the EISS model measurement and structural invariance in larger and size equivalent samples of both genders. Finally, temporal validity was not examined and in the future studies should include this aspect.

The EISS proved to be a short, valid and reliable measure of shame experience, representing a relevant addition to the existent measures. Not only it allows the evaluation of a general sense of shame, but it also encompasses the assessment of its specific dimensions of external and internal shame. The EISS may therefore be an important contribution for clinical work and research on the role of external and internal shame in human psychological development, functioning and suffering.

References

Andrews, B. (1998). Methodological and definitional issues in shame research. In P. Gilbert & B. Andrews (Eds.), Shame: Interpersonal behaviour, psychopathology and culture (pp. 39–55). New York: Oxford University Press.

Balsamo, M., Macchia, A., Carlucci, L., Picconi, L., Tommasi, M., Gilbert, P., & Saggino, A. (2015). Measurement of external shame: An inside view. Journal of Personality Assessment, 97(1), 81–89.

Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & L. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park: SAGE.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge Academic.

Castilho, P., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, J. (2014). Exploring self-criticism: Confirmatory factor analysis of the FSCRS in clinical and nonclinical samples. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 22(153–164), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1881.

Cook D. R. (1994, 2001). Internalized shame scale: Technical manual. North Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.

Cook, D. (1996). Empirical studies of shame and guilt: The internalized shame scale. In D. L. Nathanson (Ed.), Knowing feeling. Affect, script and psychotherapy (pp. 132–165). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Dearing, R. L., & Tangney, J. P. (Eds.). (2011). Shame in the therapy hour. Washington DC: APA Books.

Del Rosário, P. M., & White, R. M. (2006). The internalized shame scale: Temporal stability, internal consistency, and principal components analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.paid. 2005.10.026.

DeVellis, R. (2012). Scale development: Theory and applications (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Elison, J., Pulos, S., & Lennon, R. (2006). Shame-focused coping: An empirical study of the compass of shame. Social Behavior and Personality, 34(2), 161–168.

Else-Quest, N. M., Higgins, A., Allison, C., & Morton, L. C. (2012). Gender differences in self- conscious emotional experience: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 947–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027930.

Ferguson, T. J., & Eyre, H. L. (2000). Engendering gender differences in shame and guilt: Stereotypes, socialization, and situational pressures. In A. H. Fischer (Ed.), Gender and emotion: Social psychological perspectives (pp. 254–276). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fessler, D. M. T. (2007). From appeasement to conformity: Evolutionary and cultural perspectives on shame, competition, and cooperation. In J. Tracy, R. Robins, & J. Tangney (Eds.), Self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 174–193). New York: Guilford Press.

Gilbert, P. (1997). The evolution of social attractiveness and its role in shame, humiliation, guilt and therapy. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70, 113–147.

Gilbert, P. (1998). What is shame? Some core issues and controversies. In P. Gilbert & B. Andrews (Eds.), Shame: Interpersonal behaviour, psychopathology and culture (pp. 3–36). New York: Oxford University Press.

Gilbert, P. (2002). Body shame: A biopsychosocial conceptualisation and overview, with treatment implications. In P. Gilbert & J. Miles (Eds.), Body shame: Conceptualisation, research and treatment (pp. 3–54). London: Brunner.

Gilbert, P. (2003). Evolution, social roles and the differences in shame and guilt. Social Research, 70, 1205–1230.

Gilbert, P. (2007). The evolution of shame as a marker for relationship security. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 283–309). New York: Guilford Press.

Gilbert, P., & Andrews, B. (Eds.). (1998). Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology and culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gilbert, P., Clarke, M., Hempel, S., Miles, J., & Irons, C. (2004). Criticising and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 31–50.

Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2009). Shame, self-criticism, and self-compassion in adolescence. In N. B. Allen & L. B. Sheeber (Eds.), Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders (pp. 195–214). London: Cambridge University Press.

Goss, K., Gilbert, P., & Allan, S. (1994). An exploration of shame measures: I. the “other as Shamer scale”. Personality and Individual Differences, 17, 713–717.

Gratz, K. L., Rosenthal, M. Z., Tull, M. T., Lejuez, C., & Gunderson, J. G. (2010). An experimental investigation of emotional reactivity and delayed emotional recovery in borderline personality disorder: The role of shame. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 51, 275–285.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson. (2010). Multivariante data analysis (7th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education.

Halamová, J., Kanovský, M., Gilbert, P., Troop, N. A., Zuroff, D. C., Hermanto, N., et al. (2018). The factor structure of the forms of self-Criticising/Attacking & Self-Reassuring Scale in thirteen distinct populations. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40(4), 736–751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9675-5.

Harder, D. (1995). Shame and guilt assessment and relationships of shame and guilt proneness to psychopathology. In J. Tangney & K. Fischer (Eds.), Self-conscious emotions: The psychology of shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride (pp. 368–392). New York: Guilford.

Harder, D. W., Cutler, L., & Rockart, L. (1992). Assessment of shame and guilt and their relationships to psychopathology. Journal of Personality Assessment, 59, 584–604. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5903_12.

Harman, R., & Lee, D. (2010). The role of shame and self-critical thinking in the development and maintenance of current threat in post-traumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 17, 13–24.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance, structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Kaufman, G. (1989). The psychology of shame: Theory and treatment of shame-based syndromes. New York: Springer.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Kline, P. (2000). A handbook of psychological testing (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Kim, S., Thibodeau, R., & Jorgensen, R. (2011). Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 68–96.

Leeming, D., & Boyle, M. (2004). Shame as a social phenomenon: A critical analysis of the concept of dispositional shame. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 77(3), 375–396.

Lewis, M. (2000). Self-conscious emotions: Embarrassment, pride, shame and guilt. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 623–636). New York: Guildford Press.

Lovibond, P., & Lovibond, H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with Beck depressive and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U.

Luoma, J. B., Kohlenberg, B. S., Hayes, S. C., & Fletcher, L. (2012). Slow and steady wins the race: A randomized clinical trial of acceptance and commitment therapy targeting shame in substance use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 43–53.

Matos, M., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Duarte, C. (2012). When I don’t like myself: Portuguese version of the internalized shame scale. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 15(3), 1411–1423. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_SJOP.2012.v15.n3.39425.

Matos, M., Pinto-Gouveia, J., Gilbert, P., Duarte, C., & Figueiredo, C. (2015). The other as Shamer scale - 2: Development and validation of a short version of a measure of external shame. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 6–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.037.

Matos, M., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Gilbert, P. (2013). The effect of shame and shame memories on paranoid ideation and social anxiety. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 20, 334–349. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1766.

Murray, C., & Waller, G. (2002). Reported sexual abuse and bulimic psychopathology among nonclinical women: The mediating role of shame. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 32, 186–191. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10062.

Nathanson, D. L. (1994). Shame and pride: Affect, sex, and the birth of the self. New York: Norton & Company.

Pais-Ribeiro, J., Honrado, A., & Leal, I. (2004). Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação portuguesa das escalas de ansiedade depressão stress de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psychologica, 36, 235–246.

Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Matos, M. (2011). Can shame memories become a key to identity? The centrality of shame memories predicts psychopathology. Applied Cognitive Psychology., 25(2), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1689.

Rizvi, S. L. (2010). Development and preliminary validation of a new measure to assess shame: The shame inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32, 438–447.

Rüsch, N., Lieb, K., Göttler, I., Hermann, C., Schramm, E., Richter, H., et al. (2007). Shame and implicit self-concept in women with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 500–508.

Rybak, C. J., & Brown, B. (1996). Assessment of internalized shame: Validity and reliability of the internalized shame scale. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 14(1), 71–83.

Schalkwijk, F., Stams, G. J., Dekker, J., Peen, J., & Elison, J. (2016). Measuring shame regulation: Validation of the compass of shame scale. Social Behavior and Personality, 44(11), 1775–1791.

Saggino, A., Carlucci, L., Sergi, M. R., D'Ambrosio, I., Fairfield, B., Cera, N., & Balsamo, M. (2017). A validation study of the psychometric properties of the other as Shamer Scale-2. SAGE Open, 7(2), 2158244017704241.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Tangney, J. (1996). Conceptual and methodological issues in the assessment of shame and guilt. Behaviour. Research and Therapy, 34, 741–754.

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt. New York: Guilford Press.

Tangney, J. P., Miller, R. S., Flicker, L., & Barlow, D. (1996). Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 1256–1269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1256.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: A theoretical model. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 103–125.

Tracy, J. L., Robins, R. W., & Tangney, J. P. (Eds.). (2007). The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research. New York: Guilford.

Troop, N. A., Allan, S., Serpell, L., & Treasure, J. L. (2008). Shame in women with a history of eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 16, 480–488.

Acknowledgements

Appreciation is expressed to Constança Martins and Daniela Melo for assistance in recruitment of participants.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the research committee of the University of Queensland School of Psychology Ethics Committee with the approval number 18-PSYCH-4-77-JMC and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferreira, C., Moura-Ramos, M., Matos, M. et al. A new measure to assess external and internal shame: development, factor structure and psychometric properties of the External and Internal Shame Scale. Curr Psychol 41, 1892–1901 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00709-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00709-0