Abstract

This study examined the relationships of parents’ and children’s sibling status to parenting and co-parenting in Shanghai, China. Parents of 652 children (mean age = 61.55 months) from 12 preschools completed the questionnaire. The fathers and mothers provided demographic information and responded to items that assessed parenting style and perceived co-parenting. The results found that, in two-child families, mothers without siblings reported more authoritative parenting styles and less authoritarian parenting styles than mothers with siblings. Co-parenting positively related to authoritative parenting style and negatively related to authoritarian parenting style for both parents and regardless of parents’ and children’s sibling status. The results support the resource dilution model for Chinese families, emphasize the importance of sibling status on parenting and co-parenting, clarify gender differences, and add to the emerging discourse on China’s changing population policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Whether one spends childhood with or without siblings is one’s “sibling status,” and it is an important aspect of family structure (Dunn 1995). Sibling status in China is unique because China’s one-child policy, which began in the late 1970s, limited family size and many children born during that period had no siblings. These singletons are now adults and most of them are parents. Since the early 2000s, China has gradually been relaxing the one-child policy to allow couples to have two children (Wang et al. 2016), which has expanded the options of these parents who never had siblings to provide their children with a brother or sister. Therefore, the policy change offers unique research opportunities regarding Chinese families. Our avenue of inquiry is a quasi-experimental comparative study about the ways that both parents’ and children’s sibling status might separately and jointly influence Chinese family functioning (e.g., parenting and co-parenting).

Differences in parenting and co-parenting based on parents’ sibling status (Chen 2019) or family size (Lu and Chang 2013) are not clear because we lack relevant empirical studies. To address this knowledge gap, the present study explored those relationships in a sample of parents of preschoolers in Shanghai, China. It further examined the way that parents’ and children’s sibling status might influence the relationship between parenting style and co-parenting. The study’s theoretical contribution is its clarification of the differences between parents regarding parenting style and co-parenting behaviors that depend on their sibling status, particularly regarding cultural implications. The study’s results could suggest ways that fathers and mothers might parent under the two-child policy that differ from their own upbringing, and it might help to develop interventions that support parents.

Parenting Styles and Co-Parenting

Baumrind’s typology was one of the most widely used theory in parenting. Baumrind (1967) distinguished between authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles. Authoritative parents are characterized as highly demanding of their children with appropriate support of their autonomy and significant emotional investment. Authoritarian parents also are highly demanding, but they are low in support of their children’s autonomy and make small emotional investments. Although there is cultural concern about Baumrind’s parenting constructs (Chao 2000), evidence showed that the authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles are identified both in Western cultures (e.g., United States) and in Asia, such as Mainland China (Chen et al. 1997; Wu et al. 2002). In particular, with the rapid of social and economic development, and the introduction of western social values in recent years, Chinese parents’ parenting practices, especially in urban areas, become more and more similar to their counterparts in North America (Chen et al. 2010). Therefore, we used the authoritative and authoritarian scales because they have been well validated in China and can be equally compared with the dimensions emphasized in North America.

Recently, research on parenting has extended its reach to include couples’ cooperation in parenting (i.e., co-parenting). Co-parenting is the extent of support parents provide each other in raising their children (Feinberg 2003). Co-parenting occurs when fathers and mothers share parenting responsibilities and support each other to achieve their common child-related objectives. Although the majority of studies on co-parenting to date has been set in Western societies (see Feinberg 2003 for a review), some research is emerging elsewhere, such as China (Chen in press-a, in press-b; Kwan et al. 2015; McHale et al. 2000). The co-parenting phenomenon in Western families seems relevant to China, which strongly emphasizes family harmony (McHale et al. 2000).

Parenting and Co-Parenting in the Context of China’s Population Policy

Historically, Chinese parents have been less likely to be authoritative than authoritarian (Chao and Tseng 2002). However, Chinese parents’ parenting styles might be changing under the influence of broad social changes, including to the one-child policy, occurring in China. Of interest to the present study is the empirical research that found Chinese parents more likely to use authoritative parenting when they raise one child (Lu and Chang 2013). According to the resource dilution model (Blake 1981; Trent and Spitze 2011), every family has a limit to the resources that could be used for children, and the resources each child receives (psychological as well as material) tend to decrease as the number of children in the family (family size) increases. It follows that, during childhood, individuals without siblings obtain all the family’s child-related resources, which might explain why parents of only children are relatively likely to use a more supportive (authoritative) parenting style.

Only children’s resource monopolization seems to persist into adulthood (Chen 2018) and, even, to their own parenthood. For example, Chinese parents tend to spend a great deal of time helping their adult children by caring for the grandchildren (Goh 2009). They are considered regular caregivers whose efforts relieve their adult children’s childcare stress (Chen et al. 2011). Having one adult child means that all of one’s energies can be directed at supporting that child through the grandchildren. Consequently, parents without siblings might continue to obtain all their parents’ support, and, thus, have relatively less parenting stress. Previous studies have found that parenting stress negatively related to authoritative parenting and positively related to authoritarian parenting (e.g., Carapito et al. 2018; Chen in press-b; Frontini et al. 2016). Therefore, compared to those with siblings, parents without siblings might receive more support from their own parents that lowers their parenting stress, which, in turn, encourages authoritative parenting.

However, relatively little is known about the combined influences of parents’ sibling status and their number of children on parenting and co-parenting. This is an important time to examine the question in China because the first generation of China’s children, who grew up without siblings (under the one-child policy) are becoming parents, are allowed to have more than one child. In China, parents with two or more children reported more stress than parents of one child (Chen in press-b; Krieg 2007), which supports the resource dilution model. When there is more than one child, parents without siblings are expected to receive more support from their parents and experience less parenting stress, and, consequently, use authoritative parenting more than authoritarian parenting compared to parents with siblings raising more than one child. In contrast, parents raising one child are expected to experience less stress than parents raising multiple children, regardless of their sibling status. Therefore, parents’ sibling status might have a relatively weaker influence on the parenting style of parents raising one child.

Furthermore, Chinese fathers and mothers tend to have different parenting styles. Traditionally, Chinese fathers were considered stern parents (Chang et al. 2011) who maintained emotional distance from their family members to assert their authority over them (Li and Lamb 2013). However, during the one-child policy historical period, fathers were emotionally invested in their (only) children more than they had been in the past (when they were likely to have multiple children) (Li and Lamb 2013), and they were more likely than in the past to co-parent with the mothers (Chang et al. 2011). Since the relaxation of the one-child policy, fathers’ co-parenting support has remained important in two-children families (Chen in press-a, in press-b) because raising two children requires relatively more social resources (Kolak and Volling 2013; Szabó et al. 2010). Therefore, from the parenting stress perspective, parents without siblings who have more than one child might need more co-parenting support than if there were one child.

The Relationship between Co-Parenting and Parenting Style

The family systems perspective (Cox and Paley 2003) proposes that co-parenting and parenting are different yet interrelated subsystems in families. The ecological model of co-parenting proposed that co-parenting was associated with parenting behaviors (Feinberg 2003). Increasing evidence from Western samples suggests that co-parenting influences parenting style (Bonds and Gondoli 2007; Feinberg et al. 2007; Karreman et al. 2008), but there is limited research on that relationship among Chinese families. Xu et al. (2005) found that parents’ perceptions of social support positively related to using authoritative parenting behaviors, suggesting that co-parenting (a type of social support) may positively relate to authoritative parenting and negatively relate to authoritarian parenting. Given that there is no evidence that parents’ and children’s sibling status influences the relationship between co-parenting and parenting style, sibling status was, in this study, investigated as an exploratory factor.

Objectives and Hypotheses

The main objective of this study was to examine the influences of parents’ sibling status and their number of children on parenting style and perceptions of partner co-parenting in China. Chinese children tend to spend more time with their mothers than with their fathers (Kwan et al. 2015), suggesting that these relationships might be different for fathers and mothers, so the following hypotheses were separately tested for the fathers and mothers in the sample.

First, based on the resource dilution model, it was expected that among parents with two children, parents without siblings would express more authoritative and less authoritarian parenting behaviors and they would have more co-parenting support than parents with siblings. Second, based on the previous studies reviewed above, it was expected that co-parenting would be positively related to authoritative parenting behaviors and negatively related to authoritarian parenting behaviors. Also such relationships would be moderated by parents and children’s sibling status.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The data were derived from an ongoing longitudinal survey in Shanghai, China, on preschoolers’ developmental outcomes and their environmental antecedents. Shanghai is a metropolis on China’s east coast. The project was initially conducted in 2016, followed by two additional waves of data collected annually. Children at 12 preschools and their parents were invited to participate. Data on parents’ sibling status were collected in the second wave (2017), and, therefore, this study’s analyses used that year’s data. Before participating, informed consent was obtained from the parents and the children’s teachers. The children brought the questionnaires to the parents who completed them at home and returned them sealed within one week of receipt to their children’s teachers.

Seven hundred and eighteen children (M = 61.55 months, SD = 7.02; 53.1% female) and their parents participated in the second wave. Respondents who did not provide sufficient data on sibling status or who reported more than one parental or child sibling were dropped from the sample (9.19%). The final sample comprised 652 children (M = 61.69 months, SD = 6.92; 51.8% female). One hundred and seventy-two children (26%) had one sibling and 480 children (74%) had no siblings. Among the children with one sibling, 81 had a younger sibling (47%), 90 had an older sibling (52%), and one respondent did not report the birth order.

Regarding parents’ sibling status, 192 fathers reported siblings and 399 fathers reported no siblings. Among the mothers, 193 reported siblings and 404 reported no siblings. About 9.8% of the mothers and 9.4% of the fathers had completed middle school or high school education, 76.9% of the mothers and 67.3% of the fathers had college degrees, and 13.0% of the mothers and 22.7% of the fathers had graduate school educations.

Measures

Parenting Style

The Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ; Robinson et al. 2001) were widely used to measure parenting dimensions emphasized in North America based on Baumrind’s parenting typology. The present study adopted two subscales (i.e., authoritative and authoritarian parenting) of the modified version of the PSDQ developed by Wu et al. (2002) since the two subscales have been validated in China. It should be noted that although the permissive parenting style proposed by Baumrind was also included as a subscale in the original version of PSDQ, the construct has not been found to be strongly reliable or valid in China, and it usually is not included in research on Chinese samples (Ren and Edwards 2014; Wu et al. 2002). In addition, permissiveness may not be relevant for describing the socialization goals and values in Chinese parents (Chen in press-c). Therefore, the present study only used authoritative and authoritarian parenting subscales. The authoritative parenting subscale comprised 15 items (e.g., “I allow my kid(s) to have input into family rules”). The authoritarian parenting subscale was 11 items (e.g., “I yell and shout when my kid(s) misbehave(s)”). Fathers and mothers were asked to independently answer the questions. Response options were on a five-point Likert-type scale were 1 = never through 5 = always. The fathers and mothers were directed to respond to each item regarding their children as a whole, not exclusively about the child through whom the parent was recruited. The means of the items’ scores on each subscale were computed into composite scores. Cronbach’s α was .90 for fathers and .88 for mothers on the authoritative parenting style subscale and it was .83 for fathers and .85 for mothers on the authoritarian parenting style subscale.

Co-Parenting

Fathers and mothers independently completed the Chinese version (Chen in press-a) of the Co-parenting Relationship Scale (Stright and Bales 2003) regarding the quality of their co-parenting experiences. The respondents assessed the 14 items (e.g., “My partner backs me up when I discipline our child”) on a five-point Likert-type scale where 1 = never through 5 = always. Items on unsupportive behavior were reverse-coded; then, the mean score of the 14 items was used as a composite score. A higher score indicated a more supportive co-parenting experience. Cronbach’s α was .89 for the fathers and .89 for the mothers.

Data Analyses

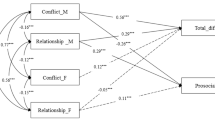

First, to test the first hypothesis (“Parents’ and children’s sibling status separately influence and have interaction effects on parenting style and perception of co-parenting”), six univariate one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were performed. Second, to test the second hypothesis (“co-parenting would be positively related to authoritative parenting behaviors and negatively related to authoritarian parenting behaviors”), regression analyses were conducted to assess the influences of children’s sibling status, mother’s/father’s sibling status, and each parent’s co-parenting on parenting behaviors with parents’ educational levels in control. A measure of parents’ educational level was included in the analyses because it often has been related to parenting variables (Chen in press-c; Xu et al. 2005). The SPSS statistical program uses the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013) as the standard model for analyzing the effects of the moderators (i.e., children’s sibling status, and mother’s/father’s sibling status). The effects of parents’ sibling status, children’s sibling status, and the measure of the quality of co-parenting were analyzed regarding their main effects on parenting styles. Two-way interaction terms between co-parenting and parents’ sibling status and between co-parenting and child’s sibling status were used to test their interaction effects on parenting style behaviors. The continuous variables were centered before the interaction terms were created. Four dependent variables were separately regressed in regression estimation models: mothers’ authoritative parenting style behaviors, mothers’ authoritarian parenting style behaviors, fathers’ authoritative parenting style behaviors, and fathers’ authoritarian parenting style behaviors.

Results

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations. The main effects of parents’ sibling status were that mothers with no siblings reported more authoritative parenting (F (1,594) = 10.64, p < .001) and higher quality co-parenting (F (1,581) = 6.81, p = .009) than mothers with siblings. Multiple children’s sibling status by mothers’ sibling status interactions emerged from these analyses. Significant interaction effects resulted for mothers’ authoritative parenting style, F (1, 594) = 5.50, p = .02, and authoritarian parenting style, F(2, 594) = 4.76, p < .03. However, there were no any significant sibling status effects and interaction effects on either mothers’ coparenting or fathers’ parenting styles and coparenting.

Because the influence of mothers’ sibling status depended on their number of children, simple effect tests were performed to separately assess the influence of mothers’ sibling status for those with one versus two children. Among mothers whose child had a sibling (two-child families), significant effects of mothers’ sibling status on authoritative parenting and authoritarian parenting were found. Mothers without siblings reported more authoritative parenting behaviors than mothers with siblings (F (1, 158) = 12.19, p < .001), and mothers without siblings reported fewer authoritarian parenting behaviors than mothers with siblings (F (1, 158) = 3.13, p = .079). There were no significant effects of mothers’ sibling status on mothers’ authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles for mothers of only children.

Tables 2 and 3 show the separate results regarding the mothers and fathers, respectively. Regarding both types of parent, quality of co-parenting positively related to authoritative parenting behaviors and negatively related to authoritarian parenting behaviors, but no interaction effects were found.

Discussion

China’s population policy has had an important role in Chinese family life (Chen and Shi 2017; Chen and Xu 2018). This is the first study to date that examines the relationships of parents’ sibling status and family size on parenting style and the quality of co-parenting in China. First, the results found that mothers without siblings who had two children reported more authoritative parenting and less authoritarian parenting than their counterparts with siblings. Second, mothers’ and fathers’ co-parenting positively related to authoritative parenting and negatively related to authoritarian parenting, regardless of parents’ or children’ sibling status. Therefore, this study provides new evidence to the research literature on sibling status as a family structure and how the number of children might influence parenting and co-parenting practices.

Consistent with the resource dilution model (Blake 1981; Trent and Spitze 2011), mothers without siblings but with two children were more authoritative and less authoritarian than mothers with siblings and two children. Resource dilution suggests that Chinese mothers without siblings might be more likely than those with siblings to receive their parents’ resources and support. These mothers might, therefore, have relatively less parenting stress if their parents help them as adults, and, consequently, they might be relatively likely to have an authoritative parenting style (which has previously been linked to less parenting stress) (Carapito et al. 2018; Frontini et al. 2016). Recently, Chen (2019) found that Chinese mothers without siblings who received more support than those with siblings might more competently care for two children. This study’s results implied that the influence of the one-child policy might not be limited to individuals without siblings while they were children; it also might influence their parenting practices when they become adults.

In addition, socialization and social learning might help to explain the findings because mothers who grew up without siblings quite likely learned from their childhood experiences and their parents’ parenting style (i.e., authoritative parenting; Lu and Chang 2013) which was transmitted from their parents’ to their parenting behaviors, regardless of their number of children. Therefore, this finding also resonates with the notion of intergenerational transmission of parenting (Belsky et al. 2009), which emphasizes that one’s childhood experiences in the family of origin influence caregiving behaviors in the adult family where he or she becomes a parent.

However, the results were limited to the mothers. Fathers’ sibling status did not significantly influence their parenting style. One reason for this finding might be that Chinese fathers spend less time with their children than mothers (Kwan et al. 2015), and mothers are primary caregivers (Li and Lamb 2013). Fathers’ lower level of involvement in raising children might be reflected in the lack of a statistically significant link between fathers’ sibling status and their parenting. In addition, there was no sibling status effect on coparenting either. It seems to suggest that familism values in which mutual support in child care was highly encouraged in Chinese families (Li and Lamb 2013). Overall, whether there was one child or two children in the family, and regardless of the parents’ sibling status, co-parenting was emphasized by the respondents (Chen in press-a; Lam et al. 2018).

In support of previous research results, co-parenting positively related to authoritative parenting and negatively related to authoritarian parenting for mothers and fathers. The result suggests that cooperation and mutual support in parents’ coordinated efforts on behalf of their children function harmoniously with authoritative rather than authoritarian parenting, regardless of one or two children or of parents’ sibling status. Co-parenting might help to relieve parenting stress (Chen in press-a), which, in turn, might promote parents’ authoritative parenting behaviors (Bonds and Gondoli 2007; Feinberg et al. 2007; Karreman et al. 2008).

However, it should be noted that, after co-parenting was included as a predictor in regression models of parenting, no main effect or interaction effect were found regarding parents’ or children’s sibling status, which indicated that co-parenting played stronger roles in parenting behaviors than does children’s or parents’ sibling status. One of possible reasons was that the coparenting and parenting conceptually overlapped because both of them had the same purpose and function for child caregiving (McHale et al. 2002). Previous literature has showed moderate associations between coparenting and parenting behaviors (e.g., Teubert and Pinquart 2010). In addition, co-parenting might be an important part of family-based social support that can be used to promote healthy parenting, whether or not the parents have siblings and regardless of the number of children. Therefore, clinical practitioners should encourage parents to support their partners in raising children. Also, as a control variable, parents’ educational attainment was associated with authoritative parenting. It was consistent with previous literature in China (Chen in press-c). Education may serve the function to teach people to have more socially acceptable practices including parenting behaviors. These findings together suggested the possible limited predictive power of sibling status in the presence of other predictors (e.g., educational levels and co-parenting). Similar findings were also demonstrated in other research. For instance, the effect of sibling status on overweight was decreased by including parents’ overweight in the regression models (Yang 2007).

The present research emphasized the important implications that sibling status may have on parenting behaviors. Within the theoretical framework of Belsky’s (1984) process model of the determinants of parenting behaviors, an individual’s developmental history influences her or his parenting behaviors and early family processes (e.g., parenting behavior) along with early-life and concurrent family structures (e.g., sibling status). It argues that these contextual conditions should be included in investigations of the functions of individual developmental history on parenting behavior. Parents’ sibling status should be considered when intervention and prevention programs to improve parenting practices are designed. In addition, the present findings supported the hypothesis derived from the ecological model of co-parenting (Feinberg 2003), that co-parenting was associated with parenting behaviors. Also, it emphasized that co-parenting may be considered as a protective factor that may decrease the influence of sibling status on parenting. Therefore, parents should be encouraged to have closely cooperative co-parenting relationships in the intervention and prevention programs to improve parenting practices.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has some limitations to consider when interpreting and generalizing the results. First, parenting style was conceptualized and its items were measured according to Western rather than Chinese parenting practices (e.g., encouragement of modesty, protection, and shaming) (Wu et al. 2002). For example, Chinese, but not Western, parents of only children might use more protective behaviors than parents of two children. Therefore, future studies should emphasize Chinese parenting characteristics.

Second, the large difference in the sample size of the two groups (about 25% with and 75% without siblings among the children, mothers, and fathers) might have biased the comparative results. However, as the first known study of the influence of parents’ sibling status on parenting behaviors, the results offer valuable insights.

Third, we focused on sibling status, but other sibling factors, such as sibling gender, composition, and age differences, might influence parenting style and co-parenting quality (e.g., Jenkins et al. 2003). Future studies should account for the influences of these factors to strengthen our understanding of sibling family structure, parenting behaviors, and co-parenting.

Last, because of the cross-sectional nature of the study, causal relationships could not be determined. In particular, one of reviewers suggested that mothers’ sibling status would influence authoritative parenting behaviors through the mediating role of co-parenting. Based on the current cross-sectional data, this hypothesis was not supported (see it in the supplementary online material). However, to assess causality and address related questions about change in parenting style and co-parenting over time, future studies should use longitudinal data.

References

Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 75, 43–88.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129836.

Belsky, J., Conger, R., & Capaldi, D. M. (2009). The intergenerational transmission of parenting: Introduction to the special section. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1201–1204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016245.

Blake, J. (1981). Family size and the quality of children. Demography, 18, 421–442.

Bonds, D. D., & Gondoli, D. M. (2007). Examining the process by which marital adjustment affects maternal warmth: The role of coparenting support as a mediator. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.288.

Carapito, E., Ribeiro, M. T., Pereira, A. I., & Roberto, M. S. (2018). Parenting stress and preschoolers’ socio-emotional adjustment: The mediating role of parenting styles in parent–child dyads. Journal of Family Studies, 1–17.

Chang, L., Chen, B.-B., & Ji, L. Q. (2011). Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in China. Parenting: Science and Practice, 11, 102–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2011.585553.

Chao, R. K. (2000). The parenting of immigrant Chinese and European American mothers: Relations between parenting styles, socialization goals, and parental practices. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21, 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(99)00037-4.

Chao, R., & Tseng, V. (2002). Parenting of Asians. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (Vol. 4, 2nd ed., pp. 59–93). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chen, B.-B. (2018). The second child: Family transition and adjustment. Shanghai, China: Shanghai Educational Publishing House.

Chen, B.-B. (2019). Chinese mothers’ sibling status, perceived supportive coparenting, and their children’s sibling relationships. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 684–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-01322-3.

Chen, B.-B. (in press-a). Chinese adolescents’ sibling conflicts: Links with maternal involvement in sibling relationships and coparenting. Journal of Research on Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12413.

Chen, B.-B. (in press-b). The relationship between Chinese mothers’ parenting stress and sibling relationships: A moderated mediation model of maternal warmth and co-parenting. Early Child Development and Care.

Chen, B.-B. (in press-c). Socialization values of Chinese parents: Does parents’ educational level matter? Current Psychology.

Chen, B.-B., & Shi, Z. (2017). Parenting in families with two children. Advances in Psychological Science, 25, 1172–1181. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2017.01172.

Chen, B.-B., & Xu, Y. (2018). Mother’s attachment history and antenatal attachment to the second baby: The moderating role of parenting efficacy in raising the firstborn child. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 21, 403–409.

Chen, X., Dong, Q., & Zhou, H. (1997). Authoritative and authoritarian parenting practices and social and school performance in Chinese children. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 21, 855–874. https://doi.org/10.1080/016502597384703.

Chen, X., Bian, Y., Xin, T., Wang, L., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2010). Perceived social change and childrearing attitudes in China. European Psychologist, 15, 260–270. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000060.

Chen, F., Liu, G., & Mair, C. A. (2011). Intergenerational ties in context: Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. Social Forces, 90, 571–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sor012.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01259.

Dunn, J. (1995). From one child to two. New York: Fawcett Columbine.

Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting, 3, 95–131. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01.

Feinberg, M. E., Kan, M. L., & Hetherington, E. M. (2007). The longitudinal influence of coparenting conflict on parental negativity and adolescent maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 687–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00400.x.

Frontini, R., Moreira, H., & Canavarro, M. (2016). Parenting stress and quality of life in pediatric obesity: The mediating role of parenting styles. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1011–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0279-3.

Goh, E. C. L. (2009). Grandparents as childcare providers: An in-depth analysis of the case of Xiamen, China. Journal of Aging Studies, 23, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2007.08.001.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Jenkins, J. M., Rasbash, J., & O'Connor, T. G. (2003). The role of the shared family context in differential parenting. Developmental Psychology, 39, 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.99.

Karreman, A., Van Tuijl, C., Van Aken, M. A. G., & Deković, M. (2008). Parenting, coparenting, and effortful control in preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 22, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.30.

Kolak, A. M., & Volling, B. L. (2013). Coparenting moderates the association between firstborn children's temperament and problem behavior across the transition to siblinghood. Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032864.

Krieg, D. B. (2007). Does motherhood get easier the second-time around? Examining parenting stress and marital quality among mothers having their first or second child. Parenting, 7, 149–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295190701306912.

Kwan, R. W. H., Kwok, S. Y. C. L., & Ling, C. C. Y. (2015). The moderating roles of parenting self-efficacy and co-parenting alliance on marital satisfaction among Chinese fathers and mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 3506–3515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0152-4.

Lam, C. B., Tam, C. Y. S., Chung, K. K. H., & Li, X. (2018). The link between coparenting cooperation and child social competence: The moderating role of child negative affect. Journal of Family Psychology, 32, 692–698. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000428.

Li, X., & Lamb, M. E. (2013). Fathers in Chinese culture: From stern disciplinarians to involved parents. In D. W. Shwalb, B. J. Shwalb, & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Fathers in cultural context (pp. 15–41). New York: Routledge.

Lu, H. J., & Chang, L. (2013). Parenting and socialization of only children in urban China: An example of authoritative parenting. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 174, 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2012.681325.

McHale, J. P., Rao, N., & Krasnow, A. D. (2000). Constructing family climates: Chinese mothers’ reports of their co-parenting behaviour and preschoolers’ adaptation. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24, 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/016502500383548.

McHale, J., Lauretti, A., Talbot, J., & Pouquette, C. (2002). Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of coparenting and family group process. In J. McHale & W. Grolnick (Eds.), Retrospect and prospect in the psychological study of families (pp. 127–166). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ren, L., & Edwards, C. P. (2014). Pathways of influence: Chinese parents' expectations, parenting styles, and child social competence. Early Child Development and Care, 185, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.944908.

Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F., & Hart, C. H. (2001). The parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire. In B. F. Perlmutter, J. Touliatos & H. G. W. (Eds.), Handbook of family measurement techniques (Vol. 3, pp. 319-321). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Stright, A. D., & Bales, S. S. (2003). Coparenting quality: Contributions of child and parent characteristics. Family Relations, 52, 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00232.x.

Szabó, N., Dubas, J. S., Karreman, A., van Tuijl, C., Deković, M., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2010). Understanding human biparental care: Does partner presence matter? Early Child Development and Care, 181, 639–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004431003717631.

Teubert, D., & Pinquart, M. (2010). The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A meta-analysis. Parenting, 10, 286–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2010.492040.

Trent, K., & Spitze, G. (2011). Growing up without siblings and adult sociability behaviors. Journal of Family Issues, 32, 1178–1204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11398945.

Wang, F., Gu, B., & Cai, Y. (2016). The end of China's one-child policy. Studies in Family Planning, 47, 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2016.00052.x.

Wu, P., Robinson, C. C., Yang, C., Hart, C. H., Olsen, S. F., Porter, C. L., et al. (2002). Similarities and differences in mothers’ parenting of preschoolers in China and the United States. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26, 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250143000436.

Xu, Y., Farver, J. A. M., Zhang, Z., Zeng, Q., Yu, L., & Cai, B. (2005). Mainland Chinese parenting styles and parent–child interaction. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 524–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250500147121.

Yang, J. (2007). China's one-child policy and overweight children in the 1990s. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 2043–2057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.024.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Shanghai Pujiang Program (No.15PJC025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Human Studies

All of the procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the APA ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 23 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, J., Chen, BB. Parenting styles and coparenting in China: The role of parents and children’s sibling status. Curr Psychol 39, 1505–1512 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00379-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00379-7