Abstract

This study aims to test the mediating effect of job crafting on the relationship between employees’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) perceptions and job performance, as well as the moderating effects of perceived organizational support (POS) on the employee CSR perceptions – job performance relationship. Utilizing survey-based data from South Korean samples, this study analyzed the responses of 181 hotel employees who reported their CSR perceptions and their own job crafting, together with their supervisor-rated job performance one month later. Job crafting fully mediated the positive relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance, the positive association between employees’ CSR perceptions and job crafting being more pronounced when organizational support was high than when it was low. Furthermore, organizational support was found to moderate the indirect effect of employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance through job crafting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

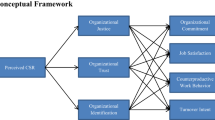

Recent micro-CSR studies have increasingly paid attention to how corporate social responsibility (CSR) influences the attitudes and behaviors of employees through their sense-making of their firm’s CSR activities (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Glavas 2016a; Rupp and Mallory 2015). Micro-CSR is referred to as “the study of the effects and experiences of CSR on individuals as examined at the individual level of analysis” (Rupp and Mallory 2015, p. 216). The micro-CSR research has suggested that employees’ sense-making of a firm’s CSR activities (hereafter referred to as their CSR perceptions) develops positive attitudinal and behavioral changes among employees (Rupp and Mallory 2015). For instance, previous research has found a positive association between CSR perceptions and a variety of employee outcomes, such as affective organizational commitment (AOC), job satisfaction, organizational identification, organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), creativity and job engagement (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; De Roeck et al. 2014; Dhanesh 2014; Glavas 2016b; Hur et al. 2018; Ko et al. 2018; Lin et al. 2010).

However, the precise mechanism through which CSR perceptions may enhance employee outcomes remains somewhat elusive. According to Glavas (2016a), many of the micro-CSR studies lack the rigor of exploring the mediators and moderators of the CSR perception–employee outcome relationship. Expanding the possible mediators and moderators is an essential step in answering the unaddressed question of causality between CSR perceptions and employee outcomes. In particular, our study aims to identify an underlying mechanism for how CSR perceptions influence employees’ job performance, something which is of the utmost importance for corporate leaders. The extant studies have found that CSR perceptions exercise an effect on employees’ job performance via organizational identification (i.e., Carmeli et al. 2007; Jones 2010). Although such research has shown that the sense-making procedures of CSR perceptions affect employees’ job performance through organizational identification, they only provide a limited understanding of how CSR perceptions affect job performance, since organizational identification is not a behavior but a cognitive and emotional propensity of an employee of an organization to identify with that organization (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Dutton et al. 1994). Thus, the primary focus of our study is to reveal how employees actually respond to CSR perceptions, triggering specific proactive behaviors (e.g., job crafting) which in turn lead to better job performance.

The existing research indicates that employees’ CSR perceptions trigger proactive and prosocial behaviors such as compassion, OCB, and creative behaviors among employees (Hur et al. 2018; Ko et al. 2018; Moon et al. 2014). Drawing upon the findings of social identity theory which suggest that individuals’ identities are predominantly shaped by interactions with others in a variety of social contexts (Tajfel 1974, 1975), the current study contends that positive sense-making about an organization through its CSR activities produces positive employee attitudes and behaviors such as job crafting, since those employees are likely to feel proud about their organization and want to sustain its positive image (Ellemers et al. 2004). In making sense of their firm’s CSR actions, employees are more likely to be cognitively and emotionally connected to that firm, leading to their prosocial and proactive behaviors (Dutton et al. 2010; Ellemers et al. 2004; Hur et al. 2018). Employees’ CSR perception encourages them to initiate social changes, promote a better workplace and relationship among members, and seek meaningfulness through their work (Aguilera et al. 2007; Aguinis and Glavas 2017; Melynyte and Ruzevicius 2008). Job crafting would be a mean through which employee can fulfill those needs through their work, and in so doing, enhance job performance. Employees are motivated to craft their jobs to achieve full control over job and work meaning, for a positive self-image in their work, and for human connections with others (Wrzensniewski and Dutton 2001). Utilizing social identity theory, we suggest that employees’ CSR perception develops a more positive identity association with regard to their membership of the organization, which may develop the intrinsic motivation to engage in job crafting, subsequently enhancing job performance. Thus, it is expected that job crafting will play a role as an important mediator in the effect of CSR perceptions on employees’ job performance.

Another objective of our study is to investigate the moderating role of perceived organizational support (POS) in the formation process between CSR perceptions, job crafting and job performance. POS is especially important in explaining the extent to which employees engage in job crafting in response to its CSR acts. POS is referred to as employees’ sense-making about the extent to which their firm fulfills its obligations and cares about them (i.e., salary, supervisor support, autonomy, empowerment, and career development opportunities) (Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002). Employees are motivated to engage in job crafting when they perceive the existence of opportunities to do so (Wrzensniewski and Dutton 2001). Since POS provides employees with the opportunities to craft their jobs so that they enjoy a sense of freedom and empowerment, we suggest that employees’ POS may be a key moderator that fosters more expansive job crafting in response to a firm’s CSR acts, which then leads to positive work outcomes such as enhanced job performance. In line with social identity theory, POS tends to fulfill esteem needs and thereby increases the incorporation of organizational membership and role status into social identity (Rhoades et al. 2001). In this respect, employees’ experiences in relation to POS become a moderating factor in influencing the engagement of job crafting in response to a firm’s CSR. Thus, we suggest that POS will moderate the mediating effect of job crafting on the relationship between CSR perceptions and job performance. In other words, we argue that the treatment effect of CSR perceptions on job performance via job crafting differs depending on the degree of POS.

In sum, our study aims to better understand the psychological mechanism involved in CSR perceptions by extending the findings of the extant research. First, we advance job crafting as a primary psychological mechanism underlying the association between CSR perceptions and job performance. We show that employees’ CSR perceptions can increase job performance through reshaping the boundaries of their jobs. Second, we attempt to examine the moderated mediation effects of POS on our mediated model. In this way, our findings that POS could affect the strength of the indirect relationship between CSR perceptions and employees’ job performance through job crafting offers a novel lens to evaluate when and how employees can enhance their job performance in response to a firm’s CSR, marking our study out as being distinct from the existing CSR and job crafting literature.

Research Background and Hypotheses

CSR Perceptions and Sense-Making

The dominant focus in the micro-CSR literature has been on the effect of CSR perceptions on changes in the attitudes and behaviors of employees (Glavas 2016a). In order to explain the effect of CSR on employees, previous studies have used the concept of ‘sense-making’, referred to as the process through which an individual provides meaning to ongoing experiences such as work (Weick 1995). CSR allows employees to positively make sense of and find meaningfulness through work (Aguinis and Glavas 2017). Employees who positively make sense of their firms due to their CSR activities are likely to identify positively and develop an emotional affinity toward their firm, leading to the enhancement of their prosocial behaviors within the organization (Baruch and Bozionelos 2010). For instance, a sizeable volume of the micro-CSR research has shown a positive relationship between CSR perceptions and various employee outcomes, such as organizational and work commitment (Dhanesh 2014; Farooq et al. 2014; Hofman and Newman 2014), job satisfaction (De Roeck et al. 2014; Dhanesh 2014), organizational identification (Kim et al. 2010), organizational citizenship behavior (Ko et al. 2018; Rupp et al. 2013), job performance (Carmeli et al. 2007; Jones 2010), improved employee relations (Glavas and Piderit 2009), creativity (Hur et al. 2018), and work engagement (Caligiuri et al. 2013; Glavas and Piderit 2009).

Although the extant research has focused on how employee perceptions of CSR influence several employee outcomes, little is known about how job crafting can be fueled by perceptions about the organization. Prior studies have found that employees’ CSR perceptions largely influence their attitudinal and behavioral responses (Cropanzano et al. 2001; Rupp et al. 2013), which develops a sense of ‘meaningful work’ and the promotion of jobs designed for productivity and creativity (Brammer et al. 2015). Research on job design has suggested that employees develop the characteristics of their job and their own perceptions of their job by searching for meaningfulness in their work (Wrzensniewski and Dutton 2001). For example, studies have found that employees’ CSR perception enhances their perceived meaning in work and value congruence at work, leading to employee engagement (Glavas 2016b). Employees’ behavioral tendencies to seek meaningfulness are largely influenced by their identities (Pratt and Ashforth 2003). Thus, organizational practices such as CSR activities shape the positive identities of employees, and in turn affects the degree to which employees view their work as meaningful. CSR activities positively highlight the image of an organization and allow employees to build up a positive identity for themselves and the organization in which they work, which facilitates meaningfulness at work (Michaelson et al. 2014). Although employees generally respond only to their personal needs to craft their jobs and do not concern themselves with what the organization wants them to do in order to alter their tasks, CSR perceptions can provide inspiration for employees to better understand the meaning of their jobs and what they can do to empower themselves, thus triggering the motivation to craft their jobs.

CSR Perception and Job Crafting

CSR involves a firm’s voluntary corporate actions and policies that reflect the firm’s ethical stance towards several types of stakeholders beyond a narrow profit-focused perspective (Aguilera et al. 2007; Aguinis and Glavas 2017). In this respect, CSR is similar to the concept of job crafting through which a firm proactively extends the relational boundary of its work beyond its wealth-creating function. Job crafting is defined as “the physical and cognitive changes individuals make in the task and relational boundaries of their work” (Wrzensniewski and Dutton 2001, p. 179). Employees can make informal changes to their job designs in order to align their jobs with their idiosyncratic interests and values, ultimately leading to increased enjoyment, meaning, and satisfaction at work. Job crafting is further categorized into task, relational, or cognitive crafting (Wrzensniewski and Dutton 2001). Task crafting is defined as changing the number or types of task, and changing the nature of those tasks (Wrzensniewski and Dutton 2001). Relational crafting refers to altering the nature or extent of how, when, or with whom employees make interactions with in the execution of their jobs (Wrzensniewski and Dutton 2001). Cognitive crafting involves cognitive changes to employees’ tasks and the relationships that make up their jobs in order to make it more personally meaningful (Wrzensniewski and Dutton 2001). Thus, job crafting represents a creative and proactive process of modifying a job’s task boundaries, altering the way employees think about the interrelationships between job tasks, and reshaping their identity and the meaning of the work in the process (Slemp and Vella-Brodrick 2014; Wrzensniewski and Dutton 2001).

The motivation for job crafting is generated from three individual needs: the need for full control over job and work meaning; the need to create and maintain a positive self-image; and the need for human connection with others (Wrzensniewski and Dutton 2001). Based upon social identity theory (Tajfel 1974, 1975), a firm’s engagement in CSR mostly enhances its reputation and internally perceived image (Turban and Greening 1997), which gives employees a sense of pride and self-esteem about their firm and nurtures a motivation to maintain the firm’s positive image (Ellemers et al. 2004). When employees consider themselves to be respected due to the positive image derived from their firm’s CSR acts, they are more likely to have higher levels of work engagement and self-worth, together with a greater confidence in their career progression as they seek to sustain the firm’s positive organizational identity (Ellemers et al. 2004). Employees who perceive their firm positively due to its CSR activities are likely to have a positive organizational identity, from which they infuse its positively-valued attributes into their self-identity. Employees’ CSR perception triggers a sense of pride and self-esteem due to their belief that they are belong to a socially responsible firm, which in turn promotes favorable behaviors such as affective organizational commitment for the further development of organizational identity (Ellemers et al. 2004). In a similar vein, we suggest that employees whose firm engages in CSR will be more likely to take control over their job and work meaning, maintain a positive self-image, and make human connections with others through job crafting in order to maintain and reinforce these positive identities. Based on the preceding discussion, we advance the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1: Employees’ perceptions of CSR are positively related tojob crafting.

Job Crafting and Job Performance

Previous studies have found a positive relationship between job crafting and several employee outcomes such as work engagement, job satisfaction, person-job fit, and job performance (e.g., Bakker et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2014; Demerouti et al. 2015a; Kim et al. 2018; McClelland et al. 2014; Siddiqi 2015). For example, Kim et al. (2018) found that employees’ job crafting is positively associated with job satisfaction. Cheng and Yi (2018) also found that job crafting is positively related to job satisfaction, and job burnout negatively mediates the association between job crafting and job satisfaction. Leana et al. (2009) found that school teachers who craft their jobs are more likely to receive higher scores for quality of care on student evaluations. Slemp and Vella-Brodrick (2014) found that job crafting is positively associated with intrinsic need satisfaction, leading to the enhancement of employee well-being. Since job crafting involves the modification of the number and type of tasks, the number and intensity of interactions with others, and adjustments to the meaning of their jobs to fit the employees’ preferences and needs, it reduces stress and burnout (Bakker and Demerouti 2007; Tims et al. 2012).

The extant research suggests that job crafting enhances employees’ competence, personal growth and learning, and persistence with future adversity, all of which produce positive outcomes in terms of goal achievement, enjoyment, and meaning (Berg et al. 2010). Wrzensniewski and Dutton (2001) suggested that job crafting is positively associated with job performance since employees change the boundaries of their job and shape a work context that fits their interests, capabilities, and values. Several empirical studies have demonstrated a positive relationship between CSR perceptions and job performance. For example, Tims et al. (2015) found that job crafting contributes to increasing work engagement, which leads to the enhancement of job performance. Bakker et al. (2012) found that job crafting is positively related to work engagement and in-role performance. Job crafters are more likely to be committed to the decision-making process, the problem-solving process, and the goals established in their workplace, all of which results in an increased motivation to perform (Ghitulescu 2006). Since job crafters have a better appreciation of how their jobs are related to others and how to make better decisions in their work, greater efficiency and productivity accrue to the firm (Ghitulescu 2006; Leana et al. 2009). Based on the preceding discussion, we advance the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 2: Employees’ job crafting is positively related to job performance.

The Mediating Role of Job Crafting

Beyond investigating the direct impact of CSR perceptions on employees’ job performance, this study seeks to reveal an underlying mechanism through which employees’ sense-making of CSR influences their job performance. Although previous research has examined the effect of CSR perceptions on employees’ job performance via organizational identification (Carmeli et al. 2007; Jones 2010), a more rigorous exploration of the mediators in the link between CSR perceptions and job performance is necessary in order to better understand how and why employee CSR perceptions affect employees’ job performance. In short, a major gap still exists in finding individual-level psychological mechanisms (mediators) of the CSR perceptions-employee outcomes link (Glavas 2016a; Rupp and Mallory 2015).

Carmeli et al. (2007) found that employee perception of CSR develops organizational identification due to their positive sense-making of their firm, which subsequently results in improved job performance. Jones (2010) found that employees who participate in volunteer programs tend to have a stronger organizational identification, which ultimately enhances in-role performance. Although these studies used organizational identification as a mediator on the relationship between CSR perception and job performance, our study used job crafting as a specific proactive behavior functioning as a mediator in the CSR perception-job performance link.

A firm’s positive reputation due to its CSR activities enhances employees’ sense of self, which has a positive impact on labor retention, productivity, and absenteeism (Riordan et al. 1997). According to social identity theory, employees who work for a socially responsible firm tend to identify with their firm since they are positively affected by their firm’s CSR activities. Specifically, they perceive that they share the same socially responsible values as their firm (Aguilera et al. 2007). It has been found that employees working for a socially responsible firm desire to have new experiences at work through sense-making since CSR extends the nature of the work boundary to include having a wider effect on society (Aguinis and Glavas 2017). In order to maintain their firm’s positive image in their own and others’ minds, employees who work for socially responsible companies are more likely to get involved in social change initiatives (Aguilera et al. 2007), to contribute to developing a better working environment (Melynyte and Ruzevicius 2008), and to seek and find meaningfulness through their work (Aguinis and Glavas 2017). Job crafting is one such avenue through which employees can pursue greater meaning through their work, and in so doing, enhance their well-being and job performance (Slemp and Vella-Brodrick 2014).

Through a desire to sustain the positive identity for their organization and themselves once triggered by the firm’s CSR activities, those who work for such a company perform more job crafting and in turn improve their job performance. We argue that job crafting might serve as a mechanism through which employees working for a socially responsible firm are able to increase their job performance. Taken together, we suggest that CSR perceptions affect employees’ job performance through the mediation of employees’ job crafting. Based on the preceding discussion, we advance the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 3: Employees’ job crafting mediates the positive relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance.

The Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support (POS)

A growing research interest has focused on the confounding variables that strengthen or mitigate the positive impact of CSR perceptions on employee outcomes (Glavas 2016a). Recent studies have revealed that individual differences (i.e., other-regarding values, environmental values and communal orientation, age, gender, national cultures) and organizational factors (i.e., POS, expected benefit to employees from CSR) moderate the relationship between CSR perceptions and employee outcomes (Brammer et al. 2007; De Roeck and Delobbe 2012; Ditlev-Simonsen 2015; Evans et al. 2011; Jones et al. 2014). Among many possible moderators, we postulate POS as a key moderator affecting the links between CSR perceptions and job crafting. POS offers opportunities within organizational contexts which facilitate employees’ job crafting, since employees are motivated to craft their jobs when they perceive organizational support such as empowerment, freedom, supervisor support, approval of autonomy, and career development opportunities (Berg et al. 2010).

In line with social identity theory, besides CSR perceptions enabling employees to positively make sense of their firm due to its positive reputation or self-image through its CSR acts (Ellemers et al. 2004), the availability of organizational support may help employees to develop a positive identity and emotional affinity toward their firm since POS makes them perceptive of the fact that their firm provides for and cares about their well-being (Rhoades et al. 2001). Rhoades et al. (2001) suggested that “perceived organizational support would also increase affective commitment by fulfilling needs for esteem, approval, and affiliation, leading to the incorporation of organizational membership and role status into social identity” (p. 825). Thus, the interactions of CSR perceptions and the possession of POS may trigger a stronger intrinsic motivation amongst employees to improve their work environment and job design, and to look for meaningfulness through work (Aguinis and Glavas 2017), which subsequently results in their engagement in job crafting.

Experiencing organizational support helps employees perceive their organization as a care system that yields various benefits such as approval and respect, pay and promotion, access to information and other means of better carrying out their work (Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002). The positive effect of CSR perceptions can be duplicated by the uplifting experience of POS from a firm, thus strengthening its positive effect. Hence, we propose that perceiving organizational support enables employees to interpret their firm’s CSR in a more positive light and to improve their work environment and job design in order to sustain its good image, which leads to increases in job crafting. Based on the preceding discussion, we advance the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 4: POS moderates the relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job crafting such that this relationship is stronger when POS is high than when it is low.

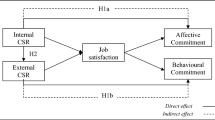

Drawing on social identity theory, we further suggest that employees’ POS performs a role as a moderator in the mediating effect of job crafting on the relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance. By positively affecting employees’ identities when dealing with their jobs, employees’ POS is likely to strengthen the indirect effect of their CSR perceptions on job performance through job crafting. Employees with a high level of POS are likely to identify with the organization (e.g., Eisenberger and Stinglhamber 2011; Sluss et al. 2008), thus making them more responsive to corporate CSR activities, which makes more opportunities to increase job crafting and job performance. Given the moderation hypothesis above and allowing for our assumptions about the moderating role of employees’ POS being correct, employees’ POS could also affect the strength of the indirect relationship between CSR perceptions and employees’ job performance, thereby suggesting the following model of moderated mediation (see Fig. 1):

-

Hypothesis 5: POS moderates the mediating effect of job crafting on the relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance such that the indirect effect of employees’ CSR perceptions on job performance is stronger when POS is high than when it is low.

Method

Participant and Procedure

Data was collected from the employees and managers of eight luxury hotels in South Korea. Having made a preliminary examination of the data available from the Korea Hotel Association (KHA) on the luxury (i.e. five-star) hotels in Korea, we randomly selected twenty such hotels and invited them to participate in our research, eight of which agreed to do so. In terms of size, location and longevity, the KHA data indicated that these hotels did not differ significantly from their counterparts. Subsequent data collection took place at two time points in order to mitigate potential problems associated with common method variance (CMV) (Podsakoff et al. 2012) and the lack of causality. 240 copies of a questionnaire along with a cover letter were delivered to the department managers in the eight hotels after they agreed to participate in this study. The department managers then distributed the questionnaires to their non-supervisory employees. To maximize privacy and minimize bias, we used Brown et al.’s (2002) survey procedure. Employees placed the completed surveys in sealed envelopes that were gathered and returned to us. The department supervisors managing the employees were also sent questionnaires by mail. Each department supervisor was asked to rate their employees and then return the surveys directly to us, at which point we matched them to the respective employee surveys. At Time 1 (T1), we asked the employees to report their perceived degrees internal and external CSR, job crafting, and their perceptions of support from the organization. At Time 2 (T2), each employee’s supervisor provided the overall ratings of the target employee’s job performance.

Out of the 240 questionnaires distributed, 181 fully-matched employee-supervisor responses were generated for the sample, giving a response rate of 75.5%. Our preliminary analysis found that 62.4% of the respondents were female, while the average age of the employees was 32.1 years (SD = 6.8) and the average length of organizational tenure was 6.7 years (SD = 6.8).

Measures

According to Brislin’s (1970) back-translation procedure, the original survey items were translated into Korean and then back-translated into English. The back-translated version of the survey items was reviewed by four management scholars and found to be equivalent to the original, indicating that the Korean version was acceptable for use. All survey items were assessed on five-point Likert-type scales (see Table 1).

First, we measured employees’ CSR perceptions with three items based on Hur et al. (2016) and Wagner et al. (2009). Second, based on Wrzensniewski and Dutton (2001)‘s three defined job crafting dimensions, we measured job crafting with twelve items from Slemp and Vella-Brodrick’s (2014) task crafting, relational crafting, and cognitive crafting scale. Scholars have advocated aggregating the sub-dimensions of job crafting since “job crafting represents the orchestration of related proactive behaviors that are jointly enacted,” (Rudolph et al. 2017, p.116). Thus, it is assumed that different sub-dimensions of job crafting reflect a latent, higher-order job crafting. Adopting Slemp and Vella-Brodrick’s (2014) procedure to construct the scale of job crafting, we aggregated employees’ scores on the three sub-dimensions to generate a single job-crafting index (e.g., Sekiguchi et al. 2017). Job performance was evaluated with four items from Williams and Anderson’s (1991) scale. To assess perceived organizational support, a four-item measure was adapted from Rhoades et al. (2001). We controlled for age, gender, and organizational tenure in all subsequent analyses, namely those variables which have been found to influence job crafting (e.g., Hur et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2017; Moon et al. 2018) and job performance (e.g., Bowen et al. 2000; Moon et al. 2018). Additionally, organization dummies representing eight hotels were controlled.

Results

Tests of Reliability and Validity

We assessed the reliability of the measurement scales using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (see Table 2). The reliability coefficients for the scales ranged from .77 to .91, which indicate sufficient levels of reliability (Nunnally 1978). CFA with M-plus 8.1 software was performed to test the convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement scales. As reported in Table 3, the hypothesized four-factor model (i.e., employees’ CSR perceptions, job crafting, job performance, and perceived organizational support) exhibited a good fit in an absolute sense (χ 2(221) = 421.82; p < .05, CFI: Comparative Fit Index = .91, TLI: Tucker Lewis Index = .90, RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation = .07, SRMR: Standardized Root Mean Square Residual = .07), and significantly fitted the data better than any other alternative measurement model. The factor and item loadings in the measurement model all exceeded .59, with all t-values greater than 2.58, which confirms the convergent validity of our study measures (see Table 1). All measures exhibited a sufficient level of reliability, with composite reliabilities ranging from .77 to .91 (see Table 2). We further evaluated the discriminant validity of the measures based on Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) procedure. We found that all average variance extracted (AVE) were higher than the squared correlation between the target construct and any of the others (see Table 2). Overall, our constructs exhibited sound measurement properties.

Hypothesis Testing

We tested our hypotheses in three steps. First, we investigated the two main effects between variables (Hypothesis 1 and 2). Second, we examined a mediation model to test Hypothesis 3. Second, to test the moderation (Hypothesis 4) and moderated mediation (Hypothesis 5) hypotheses, we integrated the proposed moderating effects and tested the overall moderated mediation analysis. Prior to hypothesis 4 and 5 analyses, all continuous variables were mean-centered (Aiken and West 1991). Finally, we employed bootstrapping (N = 5000; Shrout and Bolger 2002) to mediation, moderation and moderated mediation effects, a statistical resampling method which estimates the standard deviations of a model from a sample (Hayes 2015) to test all hypotheses using an M-plus Macro designed by Stride et al. (2015) and Hayes (2015).

First, Hypothesis 1 posits a positive relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job crafting. We found a statistically significant association between the two variables (b = .21, p < .01). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported. Second, Hypothesis 2 also predicts a positive relationship between employees’ job crafting and job performance. We found that the positive association between employees’ job crafting and job performance is significant (b = .30, p < .01), so supporting Hypothesis 2. Third, Hypothesis 3 predicts the mediating effect of job crafting on the relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance. The results suggest that the relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance is fully mediated by job crafting (b = .06, 95% CI [.02, .14]), thus supporting Hypothesis 3 (see Table 4). Table 5 demonstrates that organizational support amplifies the positive relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job crafting (b = .11, p < .05). As depicted in Table 6 and Fig. 2, the positive relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job crafting is more profound among employees with high levels of organizational support (high: b = .14, 95% CI [.01, .27]). Conversely, we detected no significant relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job crafting when employees perceived low or mean levels of organizational support (low: b = −.03, 95% CI [−.16, .11]; mean: b = .05, 95% CI [−.05, .17]), lending support to Hypothesis 4.

As a test of Hypothesis 5, we assessed a moderated mediation model. Organizational support reinforced the conditional indirect effect of employees’ CSR perceptions on job performance via job crafting (b = .032, 95% CI [.001, .093]). Table 7 illustrates that the positive indirect effect of employees’ CSR perceptions on job performance is significant for high levels of organizational support (high: b = .04, 95% CI [.01, .13]). However, when perceived organizational support is low or mean, the positive indirect effect of job crafting on job performance is insignificant (low: b = −.01, 95% CI [−.07, .03]; mean: b = .01, 95% CI [−.01, .08]), which supports Hypothesis 5.

Alternative Model

Although we employed a one-month interval of two-wave survey to decease CMV, we did not use a completed longitudinal design (e.g., cross-lag model). Furthermore, scholars have recommended a three-month time frame to reduce potential temporal influences on performance (Joshi 2010; Lechner et al. 2010; Schraub et al. 2011). Therefore, drawing on the social exchange theory (SET) literature suggesting that employees’ CSR perceptions result in increased their job performance (e.g., Carmeli et al. 2007; Jones 2010), we compared the proposed mediation model with an alternative model in which job performance contributes to job crafting. Figure 3 showed employees’ CSR wasn’t significantly related to job performance (b = .07, p > .05). Furthermore, the job performance didn’t mediate the positive relationship between employees’ CSR and job crafting (b = .009, 95% CI [−.008, .039]). These findings confirm that the proposed research model is more viable than the alternative model.

Discussion

Our study explored how a firm’s CSR affects employees’ job performance through the sense-making process drawing upon social identity theory. Beyond examining the direct effect, our goal was to provide an underlying mechanism through which CSR perceptions positively influence employees’ job performance. Thus, we examined the mediating effect of job crafting on the CSR perception–job performance relationship among frontline employees, and the differential moderating effect of organizational support on the employee CSR perception–job performance relationship. As expected, job crafting significantly mediated the link between employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance. Furthermore, POS moderated the employee CSR perception–job performance relationship in a strengthening way. In addition, POS further moderated the indirect effect of employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance through job crafting. The findings of our study contribute to a growing body of research striving to illuminate the psychological mechanisms underlying CSR perceptions.

Theoretical Implications

This research contributes to several streams of study. First, it sheds new light on the micro-CSR literature by introducing a new mediator and moderator in the link between CSR perceptions and job performance. We investigate the mediating role of job crafting as a linking mechanism between employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance. In addition, our research offers further understanding by investigating the moderating effect of POS on the employee CSR perception–job crafting linkage. Furthermore, our study explores how POS moderates the effects of CSR perceptions on job performance via job crafting in terms of a moderated mediation model.

Second, although our study did not use a multi-level modeling, our additional analysis found that the variance of CSR perceptions across groups was small but the variance of CSR perceptions across individuals was large and statistically significant (between variance CSR Perceptions = .041, p > .05, within variance CSR Perceptions = .461, p < .01). These findings account for both individual and group variance in engagement in job crafting, which is worthwhile since most variance in CSR perceptions occurs at the individual level. Individual level measures of CSR perceptions enhance explanations of engagement in job crafting. That is, each employee’s perception toward the firm is conductive to the promotion of engagement in job crafting rather than each firm’s shared perceptions of CSR as a whole. Our study confirms the argument of micro-CSR studies by demonstrating that the effects of CSR on employee outcomes can be examined at the individual level of analysis. Thus, the findings of our research are consistent with those of extant micro-CSR studies, in that they found how employees’ CSR perceptions lead to positive attitudinal and behavioral changes among employees at the individual level (Aguilera et al. 2007; Aguinis and Glavas 2017; Rupp and Mallory 2015).

Third, this research contributes to the job design/crafting literature by establishing employees’ CSR perceptions as an antecedent variable. Consistent with previous studies which suggested that a firm’s CSR can extend the boundary of job design to be more relational (Glavas and Kelley 2014; Aguinis and Glavas 2017), our study confirmed that the firm’s CSR tends to trigger employees’ relational job crafting. Grant (2008) found that employees are motivated to engage in pro-social behaviors (e.g., job crafting), especially when they perceive that they or their organization have enhanced the well-being of others. Since the nature of CSR is pro-social and relational (i.e., caring for its employees and others outside of the firm), CSR would allow employees to change the nature or extent of their interactions with others at work. Thus, this finding has crucial implications for the job crafting literature that is relatively novel and lack of many important questions about the triggers of job crafting, since it supports the notion that a work environment shaped by CSR perceptions is able to develop employees’ engagement in job crafting.

Finally, we suggested POS as a meaningful contextual variable to increase the relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job performance through their job crafting. Our finding is consistent with previous studies such as Chuang and Liao (2010) which suggested that employee behaviors in the workplace are influenced by an organizational climate of concern for employees (Shen and Benson 2016). POS (e.g., concern, trust, respect, expressing sympathy and listening carefully) may enhance employees’ intrinsic motivation to improve their work environment and job design, and meaningfulness through work, which subsequently turns into employees’ job crafting. Indeed, it is possible that if employees perceive they have been treated unfairly or have not received the support they require from the organization, they may regard CSR initiatives as a hypocrisy, referred to as “the belief that a firm claims to be something that it is not” (Wagner et al. 2009, p.79). Corporate hypocrisy is caused by the discrepancy between a company’s actual performance and its assertions (Janney and Gove 2011). Corporate hypocrisy allows employees to not only feel betrayed but also keep their distance from the firm since they wish to preserve their self-identity in terms of low levels of organizational identification (Kim et al. 2010; Ko et al. 2018). The findings of our study indicate that POS may decrease the perceived potential hypocrisy of CSR practices that underpin the successful implementation of internal CSR (i.e., CSR communication toward employees). Furthermore, this finding also extends the role of POS in the CSR literature. Glavas (2016a) suggested that POS would play a psychological safety role among employees and showed that POS mediated the relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and organizational engagement. On the other hand, our research found that POS plays the role of moderator to increase workplace behaviors such as job crafting and performance. Future research needs to clarify the role of POS on the relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and job-related outcomes.

Practical Implications

Mirroring the theoretical implications, our paper also has several important implications for practitioners. First, our study corroborates the suggestion that CSR perceptions influence employees’ job performance through job crafting. Job crafting significantly affects job-related outcomes, such as work engagement, in-role performance, and OCB, which previously have been considered important for positive impacts on crucial work outcomes (Demerouti et al. 2015b; Tims et al. 2015). Consistent with previous studies, our findings support the view that organizations’ CSR initiatives help to make positive work outcomes by stimulating job design motivation. Our study prompts practitioners to reconsider the role of CSR and job crafting as a way of developing synergy effects that increase employees’ job performance. Therefore, managers should consider organizational interventions to make strong linkages between employees’ CSR perceptions and job crafting.

Second, our study found that employees differ in their response to a firm’s CSR depending on the level of POS. That is, employees with high levels of POS are more strongly led to their CSR perceptions, which increases engagement with job crafting behavior. Managers should consider that employees should be treated fairly or have received the support they require from the organization. To improve employees’ perceptions of the amount of support they receive from the organization, the latter should provide adequate job-related resources such as rewards, job conditions or perceptions of fairness (Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002).

Third, previous studies have shown how socially responsible firms enhance employees’ sense of job design such as job crafting (Sonenshein et al. 2014). For instance, Kanter (1988) suggested that social problems can trigger employees’ creative involvement in their job. Our study also found that CSR perceptions encourage employees to engage in job crafting, ultimately leading to the enhancement of their job performance, which implies that CSR perceptions motivate employees to break out of their conventional thinking patterns and seek novel ways to contribute to both society and the company. Thus, this study prompts practitioners to proactively construct environments that embed CSR at work as a means of increasing employees’ job crafting, which generates synergy effects to enhance employees’ job performance.

Finally, in order to facilitate a work environment that embeds CSR, we suggest that managers should prepare an internal device for CSR communication, so that the narratives of positive images about the firm are shared by employees, promoting a shared recognition that their firm truly cares for society. As narratives of a firm’s CSR activities are circulated throughout the organization, employees make positive sense-making of their organizations, seeing their organization as a care-providing system and a source of social support and healing, which may trigger employees’ cognitive, relational, and task crafting. In addition, the firm can create training and development programs through HRM, so that every employee can be aware of its CSR policies and activities (Shen and Benson 2016), leading to employees’ engagement in their job crafting due to finding more meaningfulness through work.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The results of this study should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, although there was a one-month interval in this research between the measurement of the independent variable, moderator, and the mediator, and the evaluation of job performance, our data collection approach is not strictly a longitudinal design, which makes it difficult to estimate causality between our research constructs. Therefore, the causality and reciprocity among employees’ CSR perceptions, POS, job crafting, and job performance needs to be better determined in further studies by using more severe research designs.

While we collected data from several companies in the hotel industry, our research participants only comprised service employees, which inevitably limits the generalizability of these research findings. To confirm its external validity, the results of our study need to be replicated in other cultures, industries, and firms. In addition, the majority of our sample was female employees. Although this represents the typical gender composition of the hotel industry (e.g., Rhee et al. 2017), future research may consider collecting data and replicating the current findings with a more gender-balanced sample.

While examining the mediating role of job crafting is a major contribution of our study, we failed to delineate the relative importance of the three forms of job crafting (i.e., cognitive, relational, and task crafting) on the relationship between employees’ CSR perceptions and their job performance. Possibly, one form of job crafting is more or less important to a specific outcome than others. For instance, relational crafting might be more strongly related to CSR perceptions than the other forms of job crafting. Likewise, task crafting might have a stronger relationship to job performance than the other forms of job crafting. Thus, we look forward to future research that investigates the relative or differential relationship between the three forms of job crafting, CSR perceptions, and various work outcomes.

Finally, for the sake of model parsimony, we used only one boundary condition that may influence the employee CSR perception – job performance relationship. However, as interpersonal supports such as the one between coworker and supervisor also play an important role in motivating employee workplace behavior in service industry, future studies might explore three types of social support (i.e., organizational, supervisory, and coworker) and test the moderating relationships at different levels of the organizations.

References

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32, 836–863.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38, 932–968.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2017). On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. Journal of Management. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317691575.

Aiken, L., & West, S. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Ashforth, B., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14, 20–39.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 309–328.

Bakker, A. B., Tims, M., & Derks, D. (2012). Proactive personality and job performance: The role of job crafting and work engagement. Human Relations, 65, 1359–1378.

Bakker, A. B., Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., & Vergel, A. I. S. (2016). Modelling job crafting behaviours: Implications for work engagement. Human Relations, 69, 169–189.

Baruch, Y., & Bozionelos, N. (2010). Career issues. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, volume 2: Selecting & Developing Members of the organization (pp. 67–113). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Berg, J. M., Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2010). Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 158–186.

Bowen, C., Swim, J., & Jacobs, R. (2000). Evaluating gender biases on actual job performance of real people: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 2194–2215.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18, 1701–1719.

Brammer, S., He, H., & Mellahi, K. (2015). Corporate social responsibility, employee organizational identification, and creative effort: The moderating impact of corporate ability. Group and Organization Management, 40, 323–352.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1, 185–216.

Brown, T. J., Mowen, J. C., Donavan, D. T., & Licata, J. W. (2002). The customer orientation of service workers: Personality trait effects on self-and supervisor performance ratings. Journal of Marketing Research, 39, 110–119.

Caligiuri, P., Mencin, A., & Jiang, K. (2013). Win–win–win: The influence of company-sponsored volunteerism programs on employees, NGOs, and business units. Personnel Psychology, 66, 825–860.

Carmeli, A., Gilat, G., & Waldman, D. A. (2007). The role of perceived organizational performance in organizational identification, adjustment and job performance. Journal of Management Studies, 44, 972–992.

Chen, C., Yen, C., & Tsai, F. C. (2014). Job crafting and job engagement: The mediating role of person-job fit. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 37, 21–28.

Cheng, J. C., & Yi, O. (2018). Hotel employee job crafting, burnout, and satisfaction: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 72, 78–85.

Chuang, C.-H., & Liao, H. (2010). Strategic human resource management in service context: Taking care of business by taking care of employees and customers. Personnel Psychology, 63, 153–196.

Cropanzano, R., Byrne, Z. S., Bobocel, D. R., & Rupp, D. E. (2001). Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 164–209.

De Roeck, K., & Delobbe, N. (2012). Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 110, 397–412.

De Roeck, K., Marique, G., Stinglhamber, F., & Swaen, V. (2014). Understanding employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: Mediating roles of overall justice and organizational identification. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25, 91–112.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Gevers, J. M. P. (2015a). Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 87–96.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2015b). Productive and counterproductive job crafting: A daily diary study. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20, 457–469.

Dhanesh, G. S. (2014). CSR as organization-employee relationship management strategy: A case study of socially responsible information technology companies in India. Management Communication Quarterly, 28, 130–149.

Ditlev-Simonsen, C. D. (2015). The relationship between Norwegian and Swedish employees’ perception of corporate social responsibility and affective commitment. Business & Society, 54, 229–253.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 239–263.

Dutton, J. E., Roberts, L. M., & Bednar, J. (2010). Pathways for positive identity construction at work: Four types of positive identity and the building of social resources. Academy of Management Review, 35, 265–293.

Eisenberger, R., & Stinglhamber, F. (2011). Perceived organizational support: Fostering enthusiastic and productive employees. Washington, DC: APA Books.

Ellemers, N., De Gilder, D., & Haslam, S. A. (2004). Motivating individuals and groups at work: A social identity perspective on leadership and group performance. Academy of Management Review, 29, 459–478.

Evans, W. R., Davis, W. D., & Frink, D. D. (2011). An examination of employee reactions to perceived corporate citizenship. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41, 938–964.

Farooq, O., Payaud, M., Merunka, D., & Valette-Florence, P. (2014). The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. Journal of Business Ethics, 125, 563–580.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

Ghitulescu, B. E. (2006). Shaping tasks and relationships at work: Examining the antecedents and consequences of employee job crafting (unpublished dissertation). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh.

Glavas, A. (2016a). Corporate social responsibility and organizational psychology: An integrative review. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 144.

Glavas, A. (2016b). Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Enabling employees to employ more of their whole selves at work. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 746.

Glavas, A., & Kelley, K. (2014). The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24, 165–202.

Glavas, A., & Piderit, S. K. (2009). How does doing good matter? Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 36, 51–70.

Grant, A. M. (2008). Designing jobs to do good: Dimensions and psychological consequences of prosocial job characteristics. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 19–39.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22.

Hofman, P. S., & Newman, A. (2014). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment and the moderating role of collectivism and masculinity: Evidence from China. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25, 631–652.

Hur, W., Moon, T., & Ko, S. (2018). How employees’ perceptions of CSR increase employee creativity: Mediating mechanisms of compassion at work and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Business Ethics., 153, 629–644.

Hur, W. M., Shin, Y., Rhee, S. Y., & Kim, H. (2017). Organizational virtuousness perceptions and task crafting: The mediating roles of organizational identification and work engagement. Career Development International, 22, 436–459.

Janney, J. J., & Gove, S. (2011). Reputation and corporate social responsibility aberrations, trends, and hypocrisy: Reactions to firm choices in the stock option backdating scandal. Journal of Management Studies, 48, 1562–1585.

Jones, D. A. (2010). Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 857–878.

Jones, D. A., Willness, C. R., & Madey, S. (2014). Why are job seekers attracted by corporate social performance? Experimental and field tests of three signal-based mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 57, 383–404.

Joshi, A. W. (2010). Salesperson influence on product development: Insights from a study of small manufacturing organizations. Journal of Marketing, 74, 94–107.

Kanter, R. M. (1988). When a thousand flowers bloom: Structural, collective and social conditions for innovation in organizations. In B. M. Straw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior, 10, 123–167.

Kim, H. R., Lee, M., Lee, H. T., & Kim, N. M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 557–569.

Kim, H. M., Im, J. Y., Qu, H., & Namkoong, J. (2018). Antecedent and consequences of job crafting: An organizational level approach. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30, 1863–1881.

Ko, S. H., Moon, T. W., & Hur, W. M. (2018). Bridging service employees’ perceptions of CSR and organizational citizenship behavior: The moderated mediation effects of personal traits. Current Psychology, 37, 816–831.

Leana, C., Appelbaum, E., & Shevchuk, I. (2009). Work process and quality of care in early childhood education: The role of job crafting. Academy of Management, 52, 1169–1192.

Lechner, C., Frankenberger, K., & Floyd, S. W. (2010). Task contingencies in the curvilinear relationship between intergroup networks and initiative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53, 865–889.

Lin, C. P., Lyau, N. M., Tsai, Y. H., Chen, W. Y., & Chiu, C. K. (2010). Modeling corporate citizenship and its relationship with organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 357–372.

Lin, B., Law, K., & Zhou, J. (2017). Why is underemployment related to creativity and OCB? A task crafting explanation of the curvilinear moderated relations. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 156–177.

McClelland, G. P., Leach, D. J., Clegg, C. W., & McGowan, I. (2014). Collaborative crafting in call Centre teams. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87, 464–486.

Melynyte, O., & Ruzevicius, J. (2008). Framework of links between corporate social responsibility and human resource management. Forum Ware International, 1, 23–34.

Michaelson, C., Pratt, M. G., Grant, A. M., & Dunn, C. P. (2014). Meaningful work: Connecting business ethics and organization studies. Journal of Business Ethics, 121, 77–90.

Moon, T. W., Hur, W. M., Ko, S. H., Kim, J. W., & Yoon, S. W. (2014). Bridging corporate social responsibility and compassion at work: Relations to organizational justice and affective organizational commitment. Career Development International, 19, 49–72.

Moon, T. W., Youn, N., Hur, W. M., & Kim, K. M. (2018). Does employees’ spirituality enhance job performance? The mediating roles of intrinsic motivation and job crafting. Current Psychology, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9864-0.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

Pratt, M. G., & Ashforth, B. E. (2003). Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. In K. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 308–327). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Rhee, S. Y., Hur, W. M., & Kim, M. (2017). The relationship of coworker incivility to job performance and the moderating role of self-efficacy and compassion at work: The job demands-resources (JD-R) approach. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32, 711–726.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698–714.

Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., & Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 825–836.

Riordan, C. M., Gatewood, R. D., & Bill, J. B. (1997). Corporate image: Employee reactions and implications for managing corporate social performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 401–412.

Rudolph, C. W., Katz, I. M., Lavigne, K. N., & Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 112–138.

Rupp, D. E., & Mallory, D. B. (2015). Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2, 211–236.

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology, 66, 895–933.

Schraub, E. M., Stegmaier, R., & Sonntag, K. (2011). The effect of change on adaptive performance: Does expressive suppression moderate the indirect effect of strain. Journal of Change Management, 11, 21–44.

Sekiguchi, T., Li, J., & Hosomi, M. (2017). Predicting job crafting from the socially embedded perspective: The interactive effect of job autonomy, social skill, and employee status. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 53, 470–497.

Shen, J., & Benson, J. (2016). When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. Journal of Management, 42, 1723–1746.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.

Siddiqi, M. A. (2015). Work engagement and job crafting of service employees influencing customer outcomes. Journal of Decision Makers, 40, 277–292.

Slemp, G. R., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2014). Optimising employee mental health: The relationship between intrinsic need satisfaction, job crafting, and employee well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 957–977.

Sluss, D. M., Klimchak, M., & Holmes, J. J. (2008). Perceived organizational support as a mediator between relational exchange and organizational identification. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 457–464.

Sonenshein, S., DeCelles, K. A., & Dutton, J. E. (2014). It’s not easy being green: The role of self-evaluations in explaining support of environmental issues. Academy of Management Journal, 57, 7–37.

Stride, C.B., Gardner, S., Catley, N., & Thomas, F. (2015). Mplus code for the mediation, moderation, and moderated mediation model templates from Andrew Hayes’ PROCESS analysis examples. Retrieved from www.offbeat.group.shef.ac.uk/FIO/mplusmedmod.htm

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information, 13, 65–93.

Tajfel, H. (1975). The exit of social mobility and the voice of social change. Social Science Information, 14, 101–118.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 173–186.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2015). Job crafting and job performance: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24, 914–928.

Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1997). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 658–672.

Wagner, T., Richard, J. L., & Barton, A. W. (2009). Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. Journal of Marketing, 73, 77–91.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17, 601–617.

Wrzensniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26, 179–201.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hur, WM., Moon, TW. & Choi, WH. The Role of Job Crafting and Perceived Organizational Support in the Link between Employees’ CSR Perceptions and Job Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Curr Psychol 40, 3151–3165 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00242-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00242-9