Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine approach and avoidance coping strategies in the context of a natural disaster as antecedents of justice and organizational citizenship behavior. Using a multi-focal perspective of social exchange theory, the study uses both reciprocity and rationality to enhance the theoretical underpinnings of behavior in a justice context. Survey data was collected from full-time employees who had experienced a hurricane three weeks earlier (n = 255). The differences between approach and avoidance coping are clear in the results suggesting that coping strategy helps account for individual differences in justice perceptions. Findings demonstrated that employees who use approach coping strategies had higher perceptions of justice and higher levels of organizational citizenship behavior while employees who use avoidance coping strategies had lower perceptions of justice and lower levels of organizational citizenship behavior. This has implications for employers who could introduce coping skills training as a practical means of assisting employees in a disaster situation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Natural disasters create special problems for organizations trying to continue business as usual. Employees often need to work despite the disaster, but they may be unable to work due to power outages, blocked roads, or excessive damage to their home or workplace. In these stressful situations, individual coping mechanisms may alter the manner in which individuals perceive organizational justice and support or may cause employee organizational citizenship behaviors to change. It is possible that organizations may use the situation of a natural disaster to demonstrate how the organization cares about the well-being of its employees by training them to engage in certain types of coping behaviors, so that they can better deal with the effects of the disaster. The purpose of this study is to use the reciprocity and rationality principles in social exchange theory to examine the relationships between individual coping mechanisms, organizational justice, perceived organizational support, and organizational citizenship behavior in the context of natural disaster. The expectations people have of work colleagues and supervisors helping them after a disaster make interpersonal treatment and information about work particularly salient. As such we limit our analysis to interpersonal and informational aspects of justice.. The model presented is a multifocal perspective of the social exchange relationship that includes both individual and organizational-focused variables.

Theoretical Background

Social exchange theory (Blau 1964), which refers to personal interactions of two or more parties such that the action of one party is contingent upon the action of the other party, has been used to explain phenomenon such as perceived organizational support (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005; Eisenberger et al. 1986; Eisenberger et al. 2002) and organizational citizenship behavior (see Moorman and Byrne 2005, for a review) by focusing on reciprocity between an organization and an employee. The rule of reciprocity assumes that there is a general, or societal, norm, such that when Person A helps Person B, then Person B is required to help Person A or at least not harm Person A. The rule of rationality, on the other hand, suggests individuals are rational beings who will make decisions that maximize both parties’ rewards when the two parties in the exchange relationship are working toward the same goal (cooperative goal structure), but will make decisions that maximize their own rewards at the expense of the other party when they have conflicting goals (competitive goal structure).

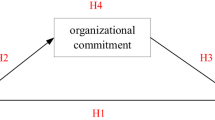

Many studies rely primarily on the reciprocity norm in social exchange theory as the basis for hypothesis development (Moorman and Byrne 2005), but this limited use of social exchange theory has been questioned. Indeed, Cropanzano and Mitchell (2005) assert that neglected components of social exchange theory should be used in an effort to help clarify organizational behavior at different levels of exchange. To address this gap, we use Meeker’s (1971) social exchange principles of both reciprocity and rationality to develop hypotheses concerning the relationship between individual coping mechanisms, organizational justice, perceived organizational support, and organizational citizenship behavior in the context of a natural disaster. The model to be tested is presented in Fig. 1.

Coping Mechanisms

The manner in which individuals cope with stress has been a subject of interest for some time. Indeed, coping strategies may vary based on appraisal of the situation (Lazarus 1993), sex (Brougham et al. 2009), or even personality traits such as self-esteem, optimism (Aspinwall and Taylor 1992), and pre-existing fears (Munson et al. 2010). Roth and Cohen (1986) describe two categories of coping responses. The first is a strategy of approaching and confronting the problem (approach coping) while the second is a strategy of avoiding the problem (avoidance coping). Research has also demonstrated that the coping mechanism chosen by the individual depends in large part upon the individual’s appraisal of the situation. If the appraisal indicates something can be done about the situation, approach coping is dominant (Lazarus 1993). Generally speaking, greater approach coping is associated with better psychological outcomes than avoidance coping (Holahan and Moos 1990; 1991; Vitaliano et al. 1987).

Additional studies have demonstrated different antecedents to different coping styles. For example, antecedents to approach coping include anger (Duhachek and Oakley 2007), high levels of optimism, and high levels of perceived control (Aspinwall and Taylor 1992), while antecedents to avoidance coping include fear (Duhachek and Oakley 2007), low levels of self-esteem, low levels of optimism and low levels of perceived control (Aspinwall and Taylor 1992). These antecedents support the idea that approach coping is likely to be used by optimistic individuals proactively solving the problem who perceive themselves to have some control over the situation. In contrast, avoidance coping is likely to be used by pessimistic individuals not proactively solving the problem who perceive themselves to have little control over the situation. It should be noted that an individual’s choice of coping mechanism depends partly upon the situation and partly upon personality, and studies have shown that individuals may use avoidance coping in the short term while dealing with an uncontrollable situation such as death of a family member, but then use approach coping later when making plans for the future (Stroebe and Schut 1999). In addition, research suggests that “…an individual who has a positive perception regarding his or her ability to cope with aversive situations will not view a potential threat from that situation to be as distressing as those with a negative perception of their coping ability,” (Munson et al. 2010, p. 309).

Coping and Justice

We believe someone engaged in approach coping will be focused on problem solving and positively re-appraising the situation (as defined by Valentiner et al. 1994), and as a result, will be likely to proactively get information they need from their supervisor and/or coworker. A person engaged in avoidance coping will try not to think of the problem and will be emotional (as defined by Valentiner et al. 1994), and as a result, is likely to not be proactive and is likely to experience anger or depression. Furthermore, relational models of justice (e.g., relational model, Tyler and Lind 1992; group engagement model, Tyler and Blader 2000) suggest individuals who perceive themselves as valued members of the group have more positive perceptions of justice than those who perceive themselves as having low value in the group. This premise is supported by research showing that belief in fair outcomes is associated with greater positive affectivity (Lucas 2009).

Employees who proactively work to obtain information from their workplace and resolve their disaster problems are more likely to view themselves as having high value while employees who avoid the problem, become emotional, and do not proactively obtain what they need from their workplace are likely to view themselves as having low value. Thus, employees engaging in approach coping are likely to have higher perceptions of interpersonal and informational justice than employees engaging in avoidance coping.

-

H1:

There is a positive relationship between approach coping and perceptions of interpersonal (informational) justice.

-

H2:

There is a negative relationship between avoidance coping and perceptions of interpersonal (informational) justice.

Coping and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Organizational citizenship behavior is defined as “…individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization…” (Organ 1988, p. 4). We believe the individual’s choice of coping mechanism after a natural disaster may impact perceptions of organizational citizenship behavior. In the situation created after a powerful storm, individuals may struggle with numerous personal problems (insurance claims, loss of power supply) that cannot be totally compartmentalized from work. For example, power outages after Hurricane Ike lasted as long as three weeks in some places. Individuals trying to return to work were constantly reminded of the damage, both at work and at home; thus, everyone was forced to confront the situation. The way individuals coped with the disaster, however, could significantly impact the individual’s attitudes and behavior toward work, and we hypothesize a positive relationship between approach coping and organizational citizenship behavior, and a negative relationship between avoidance coping and organizational citizenship behavior.

This belief is based on the premise that individuals who normally handle a stressful situation with approach coping are more likely to go out of their way to get support and resources from their boss to deal with the problem at hand. For example, an employee using approach coping may ask the supervisor for special scheduling or may ask to borrow company property such as gas-powered tools to help with emergency home repairs. Employees who take the initiative and ask for support and resources are likely to get more resources and to feel they are being treated more fairly than employees who do not ask. As a result, the individual is likely to utilize the rationality principle as described in social exchange theory and act accordingly by reciprocating through supportive employee behavior (organizational citizenship behaviors). Indeed, Meeker (1971) suggests several exchange principles simultaneously in an exchange.

The rationality principle suggests employees will make decisions that maximize their rewards in an exchange relationship (Meeker 1971). Thus individuals with approach coping styles will take action after a natural disaster to get what they need from their employer (maximize their rewards in the relationship), but these employees are not likely to take advantage of the employer because doing so could potentially hurt them in the future, causing them to lose any positive benefits from the relationship (minimize their rewards). Thus, the principle of rationality and the norm of reciprocity are working at the same time, and employees are likely to engage in positive behavior (organizational citizenship behaviors). In addition, the goals of the employee and the employer in this instance are congruent (common) in that the employee wants to solve the problem and get back to work, while the employer wants the employee to solve the problem and get back to work.

In contrast, individuals who normally handle a stressful situation with avoidance coping are more likely to “zone out”, “explode”, or do anything they can to avoid dealing with the issue. Thus, these individuals are less likely to approach their boss to get the support and resources they need, and as a result may feel they are being treated unjustly. This perceived lack of justice, however, may trigger the rule of reciprocity such that the employee who receives less help responds by not engaging in helping behaviors toward the organization in the form of organizational citizenship behaviors. In this situation, the employee and the employer have conflicting goals such that the employee wants to avoid dealing with the problem while the employer wants the employee to solve the problem and get back to work. Despite the conflicting goals, the principle of rationality and reciprocity are mutually consistent for avoidance coping because they both predict choosing the same alternative, not maximizing rewards and not reciprocating organizational citizenship behaviors as a result.

-

H3:

There is a positive relationship between approach coping and organizational citizenship behavior.

-

H4:

There is a negative relationship between avoidance coping and organizational citizenship behavior.

Multi-focal Organizational Justice

Organizational justice research has evolved from a primary focus on decision outcomes (distributive justice) to include perceptions of the decision process (procedural justice) and perceptions of personal treatment in the implementation of the decision process (interpersonal and informational justice). One of the results of classifying organizational justice into subcomponents has been to focus on the type of justice that best explains certain resulting behaviors. The multifocal perspective of justice suggests that justice perceptions can best be understood based on the source of justice dispensation, which then impacts the related behavior toward a relevant party. For example, some researchers propose that justice is viewed as related either to the system (organization) or to an agent (the person responsible for implementing the decision). This idea is the basis for the two-factor, agent-system perspective on justice (Tyler and Bies 1990).

Although the agent-system perspective of justice shows strong ties between variables at the same reference level (that is, organization to organization or person to person), the models also suggest the cognitive processing of justice perceptions can occur at different reference levels such as supervisor to organization or coworker to supervisor (Lavelle et al. 2007; Karriker and Williams 2009). Indeed, before the development of the multifocal approach, many justice studies routinely combined organization-referenced perceptions with individual-referenced perceptions. The multifocal perspective does not condemn the combination of organization-focused variables with individual-focused variables, it simply suggests justice perceptions can best be understood when the source of the justice dispensation and the resulting outcomes are acknowledged and explained.

The multifocal perspective has thus set the stage for an expanded model in which we acknowledge the respective levels of justice perspectives and examine how individual-focused justice perceptions impact organizational-focused attitudes. In a natural disaster context, informational justice and interpersonal justice seem to be the most relevant in combining individual justice perceptions with attitudes directed toward the organization. Information is a precious resource during a disaster, and individuals who want to maximize their rewards in the employee-employer exchange relationship should recognize the value of information and respectful treatment dispensed in an environment of utter chaos. This recognition of value should be correlated to perceptions of organizational support since high levels of interpersonal and informational justice suggest that the employer cares about an employee’s well-being.

Multi-focal Perceived Organizational Support

Perceived organizational support is the belief that organizations care about their employees’ well-being and value their contributions (Eisenberger et al. 1986). Several studies have found that perceptions of fairness and justice are antecedents of perceived organizational support (Lavelle et al. 2009; Loi et al. 2006; Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002). The most common explanation for this finding is grounded in social exchange theory, and is based on the idea that there is a tradeoff between employee effort and organizational rewards (Lavelle et al. 2009; Loi et al. 2006; Wayne et al. 2002). Some of the consequences of perceived organizational support include an impact on organizational commitment (Armeli et al. 1998; Eisenberger et al. 2001; Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002; Shore and Tetrick 1991), a decrease in turnover intentions (DeConinck and Johnson 2009; Loi et al. 2006) and an impact on organizational citizenship behavior (Lavelle et al. 2009; Moorman et al. 1998; Wayne et al. 2002).

Like organizational justice, perceived organizational support has also been studied from a multi-focus perspective. At the organizational level, the construct measures perceived support of the overall organization. Researchers have also identified and measured perceived support at the group level (Lavelle et al. 2009; Lavelle et al. 2007) and at the individual level as perceived supervisor support (DeConinck and Johnson 2009; Lavelle et al. 2009; Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002; Stinglhamber et al. 2006). Acknowledging the different levels of focus, we examine the relationship between justice and perceived organizational support and hypothesize a positive relationship between the variables. Although some researchers categorize supervisor-referenced justice as an individual-focused variable (Kottke and Sharafinski 1988), other researchers suggest employees consider supervisors as agents of the organization and believe supervisors act on behalf of the organization (Eisenberger et al. 1986; Eisenberger et al. 2002). Thus, we combine supervisor-referenced justice with organizational-referenced support. The supervisor is most likely the main point of contact for employees in a natural disaster context. Since some disasters can be predicted in advance, organizations are likely to disseminate information through the formal chain of communication, which means informational justice and interpersonal justice perceptions of the organization are transmitted through the actions of the organization’s designated agent, the employee’s supervisor. Employees who perceive high levels of informational and interpersonal justice in a natural disaster context are likely to recognize the employer’s effort to keep them informed as a positive action. As a result, employees are likely to reciprocate by engaging in positive actions toward the employer as predicted by the social exchange principal of reciprocity.

-

H5:

There is a positive relationship between perceptions of interpersonal (informational) justice and perceived organizational support.

Multi-focal Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Many types of organization citizenship behaviors have been identified in the literature, with almost 30 different types categorized into seven main dimensions (see Podsakoff et al. 2000, for a review). In an attempt to clarify the antecedents and consequences of organization citizenship behavior, a multi focus analytical approach further classifies organization citizenship behaviors into two broad categories consisting of behavior directed primarily towards individuals—referred to as organization citizenship behaviors toward individuals, and behavior directed primarily towards the organization (McNeely and Meglino 1994; Williams and Anderson 1991). For example, Allen (2006) found a connection between organization citizenship behaviors toward the organization and increased promotions, but not between organization citizenship behavior toward individuals and increased promotions, suggesting that behaviors directed toward the organization result in organizational-referenced consequences, but behaviors directed toward individuals do not result in organizational-referenced consequences. Supporting this view is a separate study which found a stronger relationship between perceived organizational support and organization citizenship behaviors toward the organization, two organizational-focused variables, than between perceived organizational support and organization citizenship behavior toward individuals, one organizational-focused variable and one individual-focused variable (Kaufman et al. 2001).

Some researchers, however, have suggested that organization citizenship behavior should be treated as a context-related phenomenon since specific situations may encourage exchange relationships at both the individual and organizational level (Somech and Drach-Zahavy 2004). For example, Skarlicki and Latham (1996, 1997) found that training union leaders in organizational justice principles, which encompass both individual level and organizational level exchanges, increased both organization citizenship behaviors toward individuals and organization citizenship behaviors toward the organization. Aryee and Chay (2001), also working in a union setting, found the organizational-focused variables of perceived union support and union instrumentality acted as antecedents of both organization citizenship behaviors toward the organization and organization citizenship behaviors toward individuals. Somech and Drach-Zahavy (2004) found that organizational learning, clearly an organizational-focused endeavor, was related to both forms of organization citizenship behaviors.

We propose the context-related approach to organization citizenship behavior is appropriate for the present study. The study context is the aftermath of a natural disaster in which both organizational level and individual level exchanges are likely to occur since there is a need to organize and coordinate people in the midst of confusion. Typical communication channels may not be functional, and therefore, the exchange relationships that normally require a particular chain of command become moot. In such a chaotic situation, individuals who believe the organization cares about their well-being are likely to engage in positive behaviors toward the organization as predicted by the norm of reciprocity. As perceived organizational support increases, employees are likely to respond in kind by engaging in organization citizenship behaviors. This premise is based on the reciprocity norm of social exchange theory such that when an agent of the organization treats an employee with respect, the employee reciprocates by engaging in positive behavior toward the agent and the organization.

From a rationality perspective, employees and employers have the common goal of bringing the workplace back to normal. The common goal should create a situation in which both parties in the exchange decide to maximize their rewards by helping one another. Employees are likely to consider any type of concern for well-being as organizational support if it comes from an organizational source, particularly if the typical chain of command is broken in the aftermath of the disaster. Thus, perceived organizational support at any reference level—supervisor, coworker, or organization—may result in increased organization citizenship behaviors directed toward both individuals and the organization as a whole. The principle of rationality and reciprocity are mutually consistent in this situation because they both predict choosing the same alternative, maximizing rewards and reciprocating with organization citizenship behaviors.

-

H6:

There is a positive relationship between perceived organizational support after a natural disaster and organizational citizenship behavior.

Method

Sample

Subjects for the study were recruited by students returning to school in the Southwestern United States after Hurricane Ike. Students were given an opportunity to receive extra credit by asking a full-time employee over the age of 30 to complete a series of three surveys about the recent hurricane and their experience in returning to work after the hurricane. Snowball data collection has been used frequently by researchers in recent years (Eaton and Struthers 2002; Jandeska and Kraimer 2005; Rotondo et al. 2003; Treadway et al. 2005). In a study of hurricane-induced stress, Hochwarter et al. (2008) collected data in one sample by giving undergraduate students course credit for distributing five surveys to full-time employees, similar to our method of asking students after a hurricane to distribute surveys to full time employees over the age of 30. Because we wished to measure employee attitudes within four weeks of the hurricane, a snowball sample allowed us to meet this deadline. The four week time period was to ensure that memories of the hurricane and its aftermath were not diminished. Indeed, many people in a large area surrounding the school were still without power and running water several weeks after the storm.

The cover sheet to the survey was entitled, “Employee reactions to Hurricane Ike,” and the cover sheet stated that the purpose of the survey was to learn about individual experiences in returning to work after Hurricane Ike. Participants were, thus, given the appropriate frame of reference for their responses. The thirty year age requirement was to ensure that respondents were likely to have a vested interest in property such as houses or cars, and likely to have experienced personal hardship in terms of work loss and property damage. These issues would make workplace variables such as organizational justice, perceived organizational support and organization citizenship behaviors more likely to be impacted by coping mechanisms after a natural disaster.

Hurricane Ike made landfall in the United States on September 13, 2008, and classes resumed at the university on September 22, 2008. The data for the present study are from the first survey, which was distributed and completed between October 2 and October 9. There were 255 respondents with a mean age of 43.3 who worked an average of 45.3 hours per week. Approximately 52 % of the sample respondents were male and 48 % were female. About 55 % of the respondents had a college degree or a graduate degree, 33 % had some college, and 11 % had a high school diploma. The sample was approximately 74 % White, 10 % Black, 9 % Hispanic, and 7 % other. About 30 % were paid on an hourly basis while 70 % were paid on a salary basis.

Measures

All variables were measured using either a 7-point or a 5-point Likert scale. For the perceived organizational support scale, items asked how strongly respondents agreed with statements about support, with 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. For the organizational behavior scales and the coping scales, the items asked how often respondents engaged in certain behavior or how often they reacted a certain way to stress episodes. For these two scales, 1 = never and 7 = always. The justice scales asked respondents to what extent supervisors engaged in certain behaviors. Following the example of Colquitt (2001), these items used a 5-point scale with 1 = to a very small extent and 5 = to a very large extent.

Perceived Organizational Support

Nine items were used to measure perceived organizational support (α = .92), with the items taken from Eisenberger et al. (1986). The nine items were chosen to ensure that both facets of perceived organizational support, valuation of employee contribution and care about employee well-being, were represented. Sample items include, “The organization values my contribution,” and “The organization shows very little concern for me (R).”

Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Sixteen items were used to measure organization citizenship behavior, with eight items representing organization citizenship behaviors directed toward the individual and eight items representing organization citizenship behaviors directed toward the organization. Sample items include, “How often do you help others who have been absent?” (organizational citizenship behavior directed toward the individual) and “How often do you express loyalty toward the organization?” (organizational citizenship behavior directed to the organization). These items were taken from Lee and Allen’s (2002) scale, and reliability measures were acceptable (α = .89 for organization citizenship behavior toward the individual and α = .92 for organization citizenship behavior toward the organization).

Justice

The items for interpersonal justice and informational justice were taken from Colquitt’s (2001) scale. Interpersonal justice was measured with four items (α = .89), and informational justice was measured with five items (α = .89). Sample items include, “To what extent does your supervisor treat you in a polite manner” (interpersonal justice), and “To what extent does your supervisor explain work procedures thoroughly at work” (informational justice).

Coping Response

Items measuring coping response strategies were taken from the coping response inventory (Moos 1990). For approach coping, we used the positive reappraisal and problem solving subscales. For avoidance coping, we used the cognitive avoidance and emotional discharge subscales. These four subscales were used by Valentiner et al. (1994) as representatives of approach and avoidance coping; thus, we follow their example and do the same in the present study. Each subscale consisted of 6 items, and sample items include the following: “Try not to think about the problem” (cognitive avoidance); “Yell or shout to let off steam” (emotional discharge); “Make a plan of action and follow it” (problem solving); and “Try to see the good side of the situation” (positive reappraisal). The cognitive avoidance and emotional discharge scales were added together to get one score for the avoidance coping scale (α = .84), and the problem solving and positive reappraisal scales were added together to get one score for the approach coping scale (α = .85).

Results

The data were analyzed using Partial Least Squares Graph Version 3.0 (Chin 2001), a structural modeling technique that uses partial least squares to test relationships between constructs. In many justice studies, constructs tend to be highly correlated because they often represent cognitive perceptions that are quite similar. For example, interpersonal justice and informational justice should be highly correlated, as should perceived organizational support and perceptions of justice. These constructs have been found to have discriminant validity, but the correlation between them is still quite robust as seen in Table 1. When the data are highly correlated, the regression coefficients produced using ordinary least squares regression tend to be unstable and inflated (Cohen et al. 2003, p. 419). Partial least squares uses a nonlinear iterative partial least squares algorithm that reduces the collinearity problem (Geladi and Kowalski 1986). Partial Least Squares is generally recommended as an appropriate means of analysis for small sample sizes used for theory development, but other techniques may be more appropriate for testing large sample sizes in a confirmatory sense (see Sosik et al. 2009, for a more detailed explanation). Because we are developing a new theoretical model linking coping mechanisms to justice constructs, and because the independent constructs of interest tend to be highly correlated, we believe partial least squares is the appropriate analysis to use for testing the hypothesized model.

To assess the measurement model using partial least squares analysis, it is necessary for the indicator items to load on the appropriate factor and to ensure that composite scale reliability and average variance extracted for each construct are sound. An appropriate measurement model will have item factor loadings of .60 or higher and composite scale reliability estimates of .80 or higher. In addition, average variance extracted must be higher than all the variances shared between two constructs (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Table 1 shows the composite scale reliabilities are all higher than .80 and the average variance extracted is higher than all variances shared between two constructs, while Table 2 shows that all item loadings exceed .60. These results indicate the measures represent discriminant constructs and that the measurement model is appropriate.

The results of the structural model shown in Fig. 2 list all path coefficients and R2 values. The first hypothesis states there is a positive relationship between approach coping and perceptions of organizational justice. This hypothesis was supported for interpersonal justice (b = .35, p < .001) and for informational justice (b = .38, p < .001). The second hypothesis states there is a positive relationship between approach coping and organizational citizenship behavior. This hypothesis was supported for both organization citizenship behaviors toward individuals (b = .32, p < .001) and for organization citizenship behaviors toward the organization (b = .28, p < .001). Hypotheses three and four examine the relationship between avoidance coping and perceptions of organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior. These hypotheses were generally not supported. The relationship between avoidance coping and interpersonal justice was not significant (b = −.02, p < .78) nor was the relationship between avoidance coping and informational justice (b = .06, p < .34). Avoidance coping did have a significant relationship to organization citizenship behavior toward the organization (b = −.13, p < .01) and to organization citizenship behaviors toward individuals (b = −.17, p < .001).

The fifth hypothesis states there is a positive relationship between perceptions of organizational justice and perceived organizational support. This was supported for the relationship between informational justice and perceived organizational support (b = .38, p < .001), and for the relationship between interpersonal justice and perceived organizational support (b = .21, p < .01). The sixth hypothesis examines the relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior, and it was supported for both organization citizenship behaviors toward individuals (b = .28, p < .001) and organization citizenship behaviors toward the organization (b = .51, p < .001).

Discussion

Social exchange theory, specifically the norm of reciprocity, is used frequently in the justice literature to explain behavioral exchanges in relationships, but other elements (rules) of social exchange theory, such as the principle of rationality, are often overlooked. The present study proposes that both reciprocity and rationality may be used to enhance the theoretical underpinnings of behavior in a justice context. For example, the rationality principle proposes individuals engage in rational behavior that maximizes their rewards. If the two parties in an exchange have mutual or cooperative goals, then the individuals will act in a way that allows both parties in an exchange to benefit. If the two parties in an exchange have conflicting goals, however, the individuals will make decisions to maximize their own rewards at the expense of the other party. This rational behavior combined with the norm of reciprocity allows more comprehensive explanations for individual actions. For example, our study examines coping style and justice in the context of a natural disaster. Using only the norm of reciprocity as the theoretical premise for hypotheses, researchers must assume that individuals will follow social norms without consideration of any personal cost to the reciprocating action. Adding the principle of rationality to the mix, however, allows researchers to determine if the goals of the two exchange parties are cooperative or conflicting and to develop more complex hypotheses.

Results of this study suggest that individuals engaging in approach coping after a natural disaster are more likely to have higher perceptions of organizational justice and are more likely to engage in organizational citizenship behavior than individuals engaging in avoidance coping. It is possible that individuals engaging in approach coping recognize the need to cooperate with employers after a disaster, thus creating mutual goals between the two exchange parties. Conversely, individuals engaging in avoidance coping may be more likely to focus on fulfilling their own emotional needs at the expense of the employer. Although both coping styles represent acting in a rational manner, it is possible that only those individuals engaged in approach coping recognize the importance of reciprocation in resolving the problem, while those trying to avoid the problem focus only on protecting themselves.

As with any study, there are limitations that should be considered. The data used in this study were collected at one time period, potentially leading to common method variance that may cause inflated relationships between the constructs. However, past research has already demonstrated that variables such as justice and perceived organizational support are strongly correlated, but still distinct constructs both theoretically and statistically. There is no evidence to suggest the data in this study were particularly unusual to cause concern due to the cross-sectional nature of the data collection. In addition, Doty and Glick (1998) argue the level of bias from common method variance in organizational research is rarely large enough to invalidate study findings.

A separate issue in this study concerns the timing of the data collection. We wanted to measure the variables at a time when use of the coping skills was particularly salient. Although the damage and daily disruption from the hurricane was still vividly present throughout an area hundreds of miles wide for several weeks, the actual data collection occurred about three weeks after the hurricane made landfall. The three week time lag should have been enough time for respondents to “get their bearings” and react, but it could have too much time in the sense that respondents may have begun to “reconstruct” their reactions to the disaster to reflect a more positive view of themselves. From a self-presentation perspective, it is more socially acceptable to engage in approach coping than avoidance coping. Despite this potential limitation, however, the differences between approach and avoidance coping are clear in the results. Perhaps employers could introduce coping skills training as a practical means of assisting employees in a disaster situation.

Future research should consider including cooperative or conflicting goal structure in the theoretical development of organizational justice along with additional rules from Meeker’s (1971) article on social exchange theory. Many justice theories focus heavily on group-oriented conceptualizations such as the relational model (Tyler and Lind 1992) or the group engagement model (Tyler and Blader 2000). The norm of reciprocity is a key premise in these group models in that the social exchange between the group and the individual is based on a cooperative goal structure. However, what happens when there is a conflicting goal structure between the two parties? The principle of rationality predicts a conflicting goal structure will lead to each party trying to maximize their rewards at the cost of the other party. The fairness process effect (Folger et al. 1979), which proposes that fair procedures tend to override negative reactions to unfavorable decision outcomes, suddenly becomes invalid under a conflicting goal structure. In addition, the conflicting goal structure could occur at multiple levels, making the multifocal perspective of the social exchange relationship even more important in understanding employee reactions to justice perceptions. Fairness theory (Folger and Cropanzano 2001) may be one starting point for including conflicting goal structures since it is based on individuals considering alternate outcomes based on what could and should have happened. Here, the multi-focal perspective of organizational goals, supervisor goals, and employee goals may be especially useful in determining whether the goal structure is cooperative or conflicting.

Conclusion

There is a natural social exchange relationship occurring between employee and employer—the employee offers labor in exchange for pay from the employer. Many justice theories build upon this exchange relationship by invoking the norm of reciprocity. We argue that reciprocity may not be sufficient in explaining the antecedents and consequences of justice perceptions, and examine the exchange relationship in the context of a natural disaster using both reciprocity and the principle of rationality. We also discuss the multi-focal perspective of goal structure, perceptions of justice, perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior. In conclusion, we find that individual coping style influences both individual and organizational level variables and suggest that future theory development should include more social exchange rules as defined by Meeker (1971) and should include a multi-focal perspective.

References

Allen, T. D. (2006). Rewarding good citizens: the relationship between citizenship behavior, gender, and organizational rewards. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 120–143.

Armeli, S., Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P., & Lynch, P. (1998). Perceived organizational support and police performance: the moderating influence of socio-emotional needs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 288–297.

Aryee, S., & Chay, Y. W. (2001). Workplace justice, citizenship behavior, and turnover intentions in a union context: examining the mediating role of perceived union support and union instrumentality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 154–160.

Aspinwall, L. G., & Taylor, S. E. (1992). Modeling cognitive adaptation: a longitudinal investigation of the impact of individual differences and coping on college adjustment and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 989–1003.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

Brougham, R. R., Zail, C. M., Mendoza, C. M., & Miller, J. R. (2009). Stress, sex differences and coping strategies among college students. Current Psychology, 28, 85–97.

Chin, W.W. (2001). PLS-Graph user’s guide. C.T. Bauer College of Business, University of Houston, USA.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed., p. 419). Mahway: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: a construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 386–400.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874–900.

DeConinck, J. B., & Johnson, J. T. (2009). The effects of perceived supervisor support, perceived organizational support, and organizational justice on turnover among salespeople. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 29, 333–350.

Doty, D. H., & Glick, W. H. (1998). Common methods bias: does common methods variance really bias results? Organizational Research Methods, 1, 374–406.

Duhachek, A., & Oakley, J. L. (2007). Mapping the hierarchical structure of coping: unifying empirical and theoretical perspectives. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17, 218–233.

Eaton, J., & Struthers, C. W. (2002). Using the internet for organizational research: a study of cynicism in the workplace. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 5, 305–313.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500–507.

Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P. D., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 42–51.

Eisenberger, R., Stinglhamber, F., Vandenberghe, C., Sucharski, I. L., & Rhoades, L. (2002). Perceived supervisor support: contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 565–573.

Folger, R., & Cropanzano, R. (2001). Fairness theory: Justice as accountability. In J. Greenberg & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice (pp. 89–118). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Folger, R., Rosenfield, D., Grove, J., & Corkran, L. (1979). Effects of “voice” and peer opinions on responses to inequity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 2253–2261.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

Geladi, P., & Kowalski, B. R. (1986). Partial least squares regression: a tutorial. Analytica Chimica Acta, 185, 1–17.

Hochwarter, W. A., Laird, M., & Brouer, R. L. (2008). Board up the windows: the interactive effects of hurricane-induced job stress and perceived resources on work outcomes. Journal of Management, 34, 263–289.

Holahan, C. J., & Moos, R. H. (1990). Life stressors, resistance factors, and psychological health: an extension of the stress-resistance paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 909–917.

Holahan, C. J., & Moos, R. H. (1991). Life stressors, personal and social resources, and depression: a 4-year structural model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 31–38.

Jandeska, K. E., & Kraimer, M. L. (2005). Women’s perceptions of organizational culture, work attitudes, and role-modeling behaviors. Journal of Managerial Issues, 17, 461–478.

Karriker, J. H., & Williams, M. L. (2009). Organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: a mediated multifocal model. Journal of Management, 35, 112–135.

Kaufman, J. D., Stamper, C. L., & Tesluk, P. E. (2001). Do supportive organizations make for good corporate citizens? Journal of Managerial Issues, 13, 436–449.

Kottke, J. L., & Sharafinski, C. E. (1988). Measuring perceived supervisory and organizational support. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 48, 1075–1079.

Lavelle, J. J., Rupp, D. E., & Brockner, J. (2007). Taking a multifoci approach to the study of justice, social exchange, and citizenship behavior: the target similarity model. Journal of Management, 33, 841–866.

Lavelle, J. J., McMahan, G. C., & Harris, C. M. (2009). Fairness in human resource management, social exchange relationships, and citizenship behavior: testing linkages of the target similarity model among nurses in the United States. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20, 2419–2434.

Lazarus, R. S. (1993). From psychological stress to the emotions: a history of changing outlooks. Annual Review of Psychology, 44, 1–21.

Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: the role of affect and cognition. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 131–142.

Loi, R., Hang-yue, N., & Foley, S. (2006). Linking employees’ justice perceptions to organizational commitment and intention to leave: the mediating role of perceived organizational support. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79, 101–120.

Lucas, T. (2009). Justifying outcomes versus processes: distributive and procedural justice beliefs as predictors of positive and negative affectivity. Current Psychology, 28, 249–265.

McNeely, B. L., & Meglino, B. M. (1994). The role of dispositional and situational antecedents in prosocial organizational behavior: an examination of the intended beneficiaries of prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 836–844.

Meeker, B. F. (1971). Decisions and exchange. American Sociological Review, 36, 485–495.

Moorman, R. H., & Byrne, Z. S. (2005). How does organizational justice affect organizational citizenship behavior? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 355–380). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Moorman, R. H., Blakely, G. L., & Niehoff, B. P. (1998). Does perceived organizational support mediate the relationship between procedural justice and organizational citizenship behavior? Academy of Management Journal, 41, 351–357.

Moos, R. H. (1990). Coping responses inventory manual. California: Center for Health Care Evaluation, Stanford University and Department of Veterans’ Administration Medical Centers, Palo Alto, CA.

Munson, M. S., Davis, T. E., Grills-Taquechel, A. E., & Zlomke, K. R. (2010). The effects of Hurricane Katrina on females with a pre-existing fear of storms. Current Psychology, 29, 307–319.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Paine, J. B., & Bachrach, D. G. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors: a critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Management, 26, 513–563.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support; A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698–714.

Roth, S., & Cohen, L. J. (1986). Approach, avoidance and coping with stress. American Psychologist, 41, 813–819.

Rotondo, D. M., Carlson, D. S., & Kincaid, J. F. (2003). Coping with multiple dimensions of work-family conflict. Personnel Review, 32, 275–296.

Shore, L. M., & Tetrick, L. E. (1991). A construct validity study of the survey of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 774–780.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Latham, G. P. (1996). Increasing citizenship behavior within a labor union: a test of organizational justice theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 161–169.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Latham, G. P. (1997). Leadership training in organizational justice to increase citizenship behavior within a labor union: a replication. Personnel Psychology, 50, 617–633.

Somech, A., & Drach-Zahavy, A. (2004). Exploring organizational citizenship behavior from an organizational perspective: the relationship between organizational learning and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77, 281–298.

Sosik, J. J., Kahai, S. S., & Piovoso, M. J. (2009). Silver bullet or voodoo statistics?—A primer for using the partial least squares data analytic technique in group and organization research. Group and Organization Management, 34, 5–36.

Stinglhamber, F., DeCremer, D., & Mercken, L. (2006). Perceived support as a mediator of the relationship between justice and trust. Group and Organization Management, 31, 442–468.

Stroebe, M. S., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Studies, 23, 197–224.

Treadway, D. C., Hochwarter, W. A., Kacmar, C. J., & Ferris, G. R. (2005). Political will, political skill, and political behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 229–245.

Tyler, T. R., & Bies, R. J. (1990). Beyond formal procedures: The interpersonal context of procedural justice. In J. Carroll (Ed.), Applied social psychology and organizational settings (pp. 77–98). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2000). Cooperation in groups: Procedural justice, social identity, and behavioral engagement. ix (p. 233). New York: Psychology Press.

Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 115–191). San Diego: Academic.

Valentiner, D. P., Holahan, C. J., & Moos, R. H. (1994). Social support, appraisals of event controllability, and coping: an integrative model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 1094–1102.

Vitaliano, P. P., Maiuro, R. D., & Russo, J. (1987). Raw versus relative scores in the assessment of coping strategies. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 10, 1–19.

Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., Bommer, W. H., & Tetrick, L. E. (2002). The role of fair treatment and rewards n perceptions of organizational support and leader-member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 590–598.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17, 601–617.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lilly, J.D., Virick, M. Coping Mechanisms as Antecedents of Justice and Organization Citizenship Behaviors: A Multi-Focal Perspective of the Social Exchange Relationship. Curr Psychol 32, 150–167 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-013-9172-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-013-9172-7