Abstract

This study examined the extent to which stakeholders are involved and evidence considered in urban development policies and strategies in Nigeria. With a high urban population growth rate in Nigerian cities, sustainable urban development is critical and should be hinged on viable policies that are evidence-based and consider stakeholders’ inputs and interests. A document review of policies, strategies, and plans that are relevant to urban development in Nigeria was conducted. A total of 25 documents were reviewed consisting of 11 policies, 7 plans and 6 strategies/programs/initiatives/road maps, and 1 legal act. A scoping literature review was also done to navigate assessment of the policy documents. Narrative synthesis of findings was conducted. Various stakeholders at the federal and state levels were listed in the policy and strategy documents as being involved in urban development in Nigeria, including government agencies, development partners, civil society organizations, and community groups. The lack of clarity in stakeholders’ roles in policy development was noted. Various forms of evidence were stated to have been used in policy development including examining policy antecedents, statistical data from diverse sources, country-wide experiences, and expert advice. Stakeholders’ roles in urban development in Nigeria vary across policies, and their involvement in the policy development process is not often explicit. There is a need for harmonized inclusion. Although various forms of evidence were alluded to in some Nigerian urban policies, the sources and manner of utility were somewhat unclear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Contemporary urbanization trends show that the population of urban settings is increasing and more so for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Sub-Saharan Africa, a predominantly low-income region, is among the highest urbanizing regions of the world with a cumulative growth rate of 4.0% (The World Bank, 2019). Nigeria, which is the most populous country in Africa and 6th largest in the world, has an urban population growth rate of 4.3%, with predictions that by 2050, 226 million people would be added to the country’s urban population (The World Bank, 2019). This increasing urban population growth will expectedly put pressure on critical social services (e.g., education, health, food) to meet up with the growing needs of urban dwellers in the country. There is therefore need for focused and strategic efforts to ensure that available resources match the increments in the urban population, which is an important hallmark of urban development (Freire et al., 2016).

Effective urban policies and strategies are vital to achieving adequate management of urban resources (Farrell, 2018). In recognition of this, Nigeria revised its urban development policy in 2019 and has gone ahead to integrate urban sustainability in her policies (Essen, 2019). Yet global and regional statistics show the relatively poor access to key urban resources and services in Nigeria, suggesting a weak policy base (allAfrica, 2020; Trading Economics, 2020). To drive progressive urban policies towards building sustainable urban places, participatory engagement of diverse stakeholders and fostering the use of evidence-based dialogue in improving policies are among the required ingredients (OECD Regional Development Ministerial, 2019; UN Habitat, 2015). Quality information and human resources are important requirements needed for the successful formulation of policies and programs (Onwujekwe et al., 2015; Yagboyaju, 2019). In this light, we inquire the extent to which stakeholders are involved and evidence deployed, in the formulation of Nigerian urban-related policies.

Evidence-based policymaking (EBP) (as opposed to opinion based policy making) is important in driving growth and development, especially in developing countries where the adoption of EBP is weak (Sutcliffe, 2005). EBP implies the use of the best available evidence from systematic research, rationally integrated with the experience, judgment, and expertise of policy makers in making policies and informing future decisions (Davies, 2004; Evidence-Based Policymaking Collaborative, 2016). There are several policies impacting urban areas in Nigeria, but how much EBP is deployed in the development of these policies is poorly examined in literature. Thus, the integration of evidence in the policy making process especially in LMICs and particularly in Nigeria is weak (Olomola, 2007; Uzochukwu et al., 2016). The disconnect between researchers and policy makers, the weak and unreliable research institutions, and the poor research outputs in Nigeria have been blamed for the poor linkages between policy makers and researchers (Obadan & Uga, 2017; Uzochukwu et al., 2016). Could this also be a lacuna for urban-focused policies in Nigeria?

Stakeholder participation in policy development is another key ingredient in policy formulation and implementation. In the policy arena, stakeholders often refer to persons or groups who are directly or indirectly affected by policies. Stakeholders are also those who may have interests in the policies or have the ability to influence policy outcomes either positively or negatively (OECD Regional Development Ministerial, 2019). Stakeholders include a wide array of actors from formal representatives across the levels of government to communities, regulators, businesses, civil society organizations, the academic community, multinational agencies, and development partners. Studies that have considered resources utilized within policy formulation in Nigeria commonly report that policies in the country are often suboptimal in their achievements, as they suffer poor implementation, which partly is a function of the level of stakeholders involvement in the formulation and implementation of these policies (Bolaji et al., 2015; Onwujekwe et al., 2015; Popoola, 2016; Usman, 2010). While poor implementation features as problematic to policies in Nigeria (Okoroma, 2006; Yagboyaju, 2019), very little is argued about the formulation process. Policy development process involves identifying and recruiting the human resources that should be involved in driving the policies. Again, not so much is talked about the informational resources that should guide the formulation of these policies in order to make them effective during implementation. These setbacks within policy formulation process in Nigeria disprove the usual narrative about policies in Nigeria being so good on paper but bedeviled by poor implementation processes (Popoola, 2016; Yagboyaju, 2019). When policies suffer significant setbacks in formulation as noted above, the chances of policy success are impacted. We hope to examine to what extent Nigerian urban policies take cognizance of (quality) evidence as well as involve stakeholders in the policy formulation process.

Although urban policies cover many sectors (e.g., housing, the environment, sanitation, education, agriculture, food/nutrition, health, security), for the sake of specificity, the current study will focus on urban policies that reflected issues around health and food/nutrition. Health and food/nutrition concerns are important areas of interest for Nigeria and areas where indices equally show that Nigeria is underperforming. Health indices reveal that Nigeria maternal death rates stand at 23% and that there is high burden of communicable diseases (UNAIDS, 2020; World Health Organization, 2018a, b). Non-communicable diseases are also on the rise in the country (WHO, 2018b). Health equity is abysmal as a 2018 data shows that 97% of Nigerians do not have any health insurance (Varrella, 2021). The food and nutrition landscape of Nigeria is also underperforming as the food and nutrition statistics show that under five stunting is at 43.6%, while anemia affects nearly half of women of reproductive age (Global Nutrition Report, 2020). The global climate crisis and sporadic violence (Orjiakor et al., 2020) across farming communities in Nigeria further threaten food supply. The numerous health and food/nutrition problems facing Nigeria justifies our intention to focus on policies in these areas.

This study therefore seeks to analyze the extent to which evidence and the involvement of stakeholders are considered and used in the formulation and implementation of urban polices in Nigeria. Drawing insights from critical evidence and involving a wide array of relevant stakeholders in policy formulation process helps to achieve a wider coverage of an issue of concern (Barry & Edgman-Levitan, 2012). A detailed analysis of policy documents can help improve the chances of better future policy making and implementation (Cheung et al., 2010). We believe that urban policies will be better if evidence is utilized and a broad range of stakeholders are involved in policy formulation/implementation. Analyzing stakeholders’ involvement and the extent to which evidence is used in policy formulation and implementation will help highlight key lapses that policy makers could learn from and possibly reveal potential lapses and opportunities within and across policies. Lessons can then be drawn for future policy development.

Methods

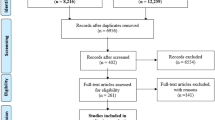

The study involved critical review of national and subnational policies, strategies, and plans in urban development, as well as a scoping review of journal articles that reported findings from evaluation of urban development policies in Nigeria. This is part of a larger study that set out to investigate social inclusion in urban development policies in Nigeria with a focus on health and nutrition. With the exclusion of the Urban and Regional Planning Act which was published in 1992, the review included only documents that were published in English language within 1999–2020.

All the researchers met severally in research meetings to define and refine the focus of the review. Through brainstorming and independent literature search around the topic of interest, we generated terms/keywords to be used in the systematic search of online resources. These keywords were then designed into set of Boolean operators. A Microsoft Excel template for identifying and extracting information from policy documents and related literature, including journal articles, was designed and vetted by the team members. Information such as full citation of the document (i.e., publication details), nature of the document (policy, strategic plans etc.), policy objectives, information on the stakeholders involved in the development/implementation, information on the use of evidence to inform the policy/plan etc. were charted in the template. Seven of the authors independently searched for policy documents using the prepared Boolean operators and harvested information using the designed template. Online databases including Google search engine, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) were used for the web search. Websites and other online resources of government agencies were searched for policy documents. Websites for the Ministries of Agriculture, Health, Housing, Environment, Lands and Urban Planning, and Office of SDGs in Nigeria were visited in search of policy documents. Websites of non-government agencies such as UN-Habitat, United Nations Development Project (UNDP), World Bank, Africa Development Bank (AfDB), UNFPA, and UNICEF were also searched for resources. The electronic search was performed using various combinations of these keywords including urban development, urban planning, sustainable, sustainability, social inclusion, access to healthcare, access to food, access to nutrition, and access to resources. For national policy documents that were unavailable online, individual visits were made to key government agencies, and requests were made for the documents. Documents were then distributed among the reviewers for independent information extraction. The search for electronic and paper-only documents was performed for 3 months, starting from the beginning of March to the end of May 2020.

Data was extracted verbatim from the source documents by the seven independent reviewers and pasted in a uniform Excel template developed to capture information on key characteristics of documents as well as thematic areas on stakeholder involvement in urban development and evidence used in policy formulation. Specific themes on stakeholder involvement included names and organization of key stakeholders, roles of stakeholders, strengths, and weaknesses of stakeholders. The thematic areas on evidence use were types of evidence and roles of evidence. Several research meetings were held to merge the findings from the seven different reviewers. The merged findings were then rotated across all authors to check that all findings are reflected and there were no omissions. Narrative synthesis of data was performed along the previously highlighted themes for stakeholder involvement in urban development and evidence use in policy formulation.

Conceptual Framework

The policy space is complex because of the diverse influencers that are involved, as well as the objectives and needs those policies are expected to achieve. There is also no consensus model to assess policy documents. To conduct a policy document analysis, we adopt Cheung et al. (2010) policy document review approach, which drew from the von Wright’s logic of events model described by Rütten et al. (2003). The von Wrights’ (1976) logic model describes policy action to arise from a combination of determinants including abilities, duties, opportunities, and wants. Rütten et al. (2003) identified 8 criteria with which to evaluate/analyze health policies. These criteria are accessibility, policy background, goals, resources, monitoring and evaluation, political opportunities, public opportunities, and obligations. However, the policy analysis framework advanced by Rutten et al. was adapted by Cheung et al. (2010) in their study that assessed health policies in Australia. The Cheung et al. adaptation added in more descriptive criteria (e.g., the involvement of multiple stakeholders) and de-emphasized criteria that is difficult to judge by looking at policy documents (e.g., the population support the action). The Cheung et al. policy analysis framework succinctly captures our focus in the current study — focus on the use of evidence and stakeholders. Box 1 shows the elaborate policy analysis template presented by Cheung et al. The areas we evaluated in this study are in bold. The criteria of policy background and public opportunities correspond to the use of evidence and involvement of stakeholders, respectively. We then go further to tease out the roles of stakeholders and the use of evidence in Nigerian urban policies.

Box 1

A. Accessibility 1. The policy document is accessible (hard copy and online) | |

B. Policy background (source of policy) 1. The scientific grounds of the policy are established 2. The goals are drawn from a conclusive review of literature 3. The source of the health policy is explicit i. Authority (one or more persons, books, scientific articles, or sources of information) ii. Quantitative or qualitative analysis iii. Deduction (premises that have been established from authority, observation, intuition, or all three) 4. The policy encompasses some set of feasible alternatives | |

C. Goals 1. The goals are explicitly stated [the goals are officially spelled out] 2. The goals are concrete enough (quantitative where possible and qualitative where not) to be evaluated 3. The goals is clear in its intent and in the mechanism with which to achieve the desired goals yet does not attempt to prescribe in detail what the change must be 4. The action centers on improving the health of the populations 5. The policy is supported by evidence of external consistency in logically drawing a health outcome from the goals and policy outcome 6. The policy is supported by internal validity in logically drawing a health outcome from the goals and policy outcome | |

D. Resources 1. Financial resources are addressed (there are sufficient financial resources) - The cost of condition to community has been mentioned - Estimated financial resources for implementation of the policy is given - Allocated financial resources for implementation of the policy are clear - There are rewards/sanction for spending the allocated resources on other programs 2. Human resources are addressed [there is enough personnel] 3. Organizational capacity is addressed [my organization has the necessary capacities] | |

Monitoring and evaluation 1. The policy indicated monitoring and evaluation mechanisms 2. The policy nominated a committee or independent body to perform the evaluation 3. The outcome measures are identified for each of the explicit and implicit objectives 4. The data, for evaluation, collected before, during, and after the introduction of the new policy 5. Follow-up takes place after a sufficient period to allow the effects of policy change to become evident 6. Other factors that could have produced the change (other than policy) identified 7. Criteria for evaluation are adequate or clear | |

F. Political opportunities 1. Cooperation between political levels involved (federal, state, area health) has either worsened or improved 2. Support from other sectors (economy, science, justice) has either worsened or improved 3. The political climate has either worsened or improved 4. Cooperation between public and private organizations has either worsened or improved 5. The lobby for the action has either worsened or improved | |

G. Public opportunities 5. The media’s interest has either worsened or improved 6. The population supports the action 7. Multiple stakeholders are involved 7. Primary concerns of stakeholders recognized and acknowledged to obtain long-term support 9. There is media’s interest | |

H. Obligations 1. The obligations of the various implementers are specified — who has to do what? 2. The action is part of health professionals’ existing duties 3. Scientific results are compelling for action 4. Health professional obliged to the population to act in this area |

Results

We reviewed a total of 25 documents comprising 11 policies, 7 plans and 6 strategies/program/initiatives/roadmaps, and 1 legal act. Robust evaluation of policies in journal articles was scarce. We also conducted a scoping literature review of peer-reviewed articles and professional perspectives often offered by development agencies evaluating specific funded national, state, or regional policies/programs within health and food/nutrition policies within urban settings. However, the theme of stakeholders or evidence was often times not the explicit focus of the articles reviewed. All the documents that were reviewed were structured to target the improvement of lives and wellbeing in Nigeria. However, the documents had divergent aims and targets, with some (e.g., Nigerian Industrial Revolution Plan, National Integrated Infrastructure Master Plan) aiming to improve physical infrastructure to improve access to food and healthcare, and others (e.g., Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative, NURHI) targeted health issues, while some others (e.g., Agriculture Transformation Agenda, ATA) specifically aimed to improve food availability. Some documents had a predominant economic outlook (e.g., Economic Recovery Growth Plan), with the plan of supporting economic growth and consequently impact health and food-related outcomes. It is important to note that subnational/state-level policies are rare to find. However, some programs were designed to be implemented in selected states or regions (e.g., NUHRI). Subnational-/state-driven policy documents/programs were scarce. However, some programs (e.g., the NUHRI and the ATA) were focused on specific states/regions of Nigeria. State-driven programs such as the Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (The World Bank, 2006) was also found. Adama (2020) also highlighted evaluations of urban development projects (Lagos Megacity Project (LMCP).

Although most policies were not exclusively urban-focused, urban themes resonated across the policies that were reviewed. Connectivity to urban places, specific cities (in plans that focused on specific places), or the description of infrastructures that define urban spaces were featured in the policies documents. Other themes that featured include access to good water and sanitation facilities, housing, and social welfare. Table 1 features the policy documents reviewed and the assessment of whether they met conditions for stakeholder involvement and utility of evidence in line with the Cheung et al. (2010) approach.

The rest of the results are structured according to three areas, namely, (i) roles of stakeholders in urban development; (ii) strengths and weaknesses of stakeholders in urban development; and (iii) roles of evidence in urban development.

Roles of Stakeholders in Urban Development Policies and Strategies in Nigeria

Various stakeholders were listed in the policy and strategy documents as being involved in urban development in Nigeria. There is a variety of approach in reporting the role of stakeholders in policies. While few policy documents (e.g., National Health Policy) reports a stakeholders meeting to steer the policy document, other policies (e.g., the Nigerian Industrial Revolution Plan) acknowledge the role of variant stakeholders within the document but does not depict the contributory roles of different stakeholders in policy formulation. Apart from a few policies that described the active and specific roles of stakeholders in policy development, other policies merely reported the participation of stakeholders often times in the Forward or Acknowledgement sections of the policy document. The participatory roles of the stakeholders are barely described. However, a robust introduction that gives a situational analysis of the state of things in a specific sector is often given in more recent policy documents. These introductory notes highlight contextual conditions including a brief appraisal of previous policies and also feature stakeholders who played and/or are expected to play roles in the hitherto policy. These stakeholders are disaggregated into government and non-government actors, and the government actors are disaggregated into federal and state/local government actors. Tables 2, 3 and 4 highlight the stakeholders, the policies where they were mentioned, and their stated roles in these policies.

Table 2 shows the federal-level government stakeholders. A total of 16 actors were identified including ministries, units, regulatory and planning commissions, advisory and steering committees, and implementation groups/councils. The roles of the federal-level stakeholders include resource mobilization, deciding and defining policy options, coordination and supervision of policy implementation, maintenance of information systems, collaboration with subnational actors, and technical support to states and local governments.

At the state and local government levels, there were some equivalents of federal-level actors including the State Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development that replicates the roles of its federal counterpart at the state level. The planning authorities were replicated at all three levels of government, and their roles were similar including monitoring and resource mobilization at the federal and state levels and the adoption of local plans at the local government level (Table 2).

Table 4 highlights the groups of non-state actors listed as role players in urban development in Nigeria. The organized private sector and international organizations were listed in three policies/plans as key role players in resource mobilization, technology adoption, and capacity building. For instance, the World Bank was key to financing the Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project (LMDGP), with over $200 m committed to it (Adama, 2020). Other stakeholders involved in both projects include the Lagos State Government, civil society organizations (CSOs), and community development agencies (CDAs). Community groups were also listed in many policies/plans as role players in planning, implementation, community mobilization, and monitoring of urban assets and infrastructure (e.g., MNODF).

In some of the urban development policies, there were some overlaps in stakeholders’ roles, and such overlaps could contribute to the lack of clarity. For instance, the National Urban Development Policy (2012) duplicates the role of coordination for three stakeholder groups including the federal government, the nodal ministry, and the Regulatory Commission.

A fairly consistent pattern is noted across policy documents. The federal ministries were often the leading actors in the initiation of policies, with state-level arms and local government units positioned to represent and drive the policy initiatives at the state and local government levels. Technical working groups, task groups, or steering committees were also common across policies and seem to have piloting tasks in the policy formulation process. State and local government authorities consistently appear as critical stakeholders upon whom the success of policies is hinged. NGOs and CBOs were also commonly identified across policies and are expected to play roles in financing as well as heralding accountability. However, grass root actors are often not accommodated in urban policy designing. For instance, local waste collectors and the informal waste economy actors were reported to be ignored and not involved in urban waste management policies/programs (Nzeadibe & Anyadike, 2012; Oguntoyinbo, 2012).

Policy documents were not always specific as to who performs which functions and many roles were assigned to “the government” (see the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2012a). Specific roles were sometimes assigned to the federal, state, and local governments and the urban development boards/authorities across these levels of government. As well, the National Housing and Urban Development Regulatory Commission was occasionally recognized and assigned specific roles as key stakeholders. The private sector was also acknowledged within policy documents. However, these stakeholders were not often specified to be involved in the designing and developing the policy. The Federal Republic of Nigeria (2012b), for instance, did not specify who was involved in the development of the policy; however, a broad range of actors were identified and assigned roles within the policy. At the federal-level, the federal government and federal institutions including the Federal Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development, the Federal Capital Territory Administration, the Federal Housing Authority, the Federal Mortgage Bank, the Central Bank of Nigeria, Securities and Exchange Commission, and the Standard Organisation of Nigeria were identified. Also state and local governments were identified to have responsibilities to deliver housing. Communities, private sector actors, and multilateral agencies were also expected to partake in housing delivery. The broad range and mix of stakeholders identified within the NHP showcases some strength if synergy and cooperation are assured. However, housing needs are even more pressing currently, raising doubts as to how much of the policy was adequate, pursued, and implemented (Saidu & Yeom, 2020). Again, the specific office/persons expected to undertake action within the mentioned stakeholders were missing in the policy, weakening the possibility of stimulating action.

Policy documents that were recently published tended to be more sophisticated and extensive in identifying a broader range of stakeholders and specifying their roles. The Sanitation Road Map (Making Nigeria Open-Defecation-Free by 2025) was commissioned by the Federal Ministry of Water Resources and in collaboration with UNICEF. Several grass root stakeholders/actors were identified to be key in achieving the goals of the map. The ministries of Health, Education, Environment, Women Affairs, and Housing and Urban Development alongside their state counterparts and local government’s departments and units were identified as key stakeholders. Other role players include non-government organizations, civil society organizations, community-based organizations, donor agencies, and development partners. The roadmap has a well laid out implementation plan and timeline and highlights the critical ingredients, such as political will and financial commitment, which are needed for the realization of its goals. Although it is stated in the road map that several agencies supported its development, it is unclear which specific agencies were involved and what contributions were made. The National Integrated Infrastructure Master Plan (NIIMP, 2015) is an example of a policy that was developed through an elaborate inclusive process. The NIIMP involved different levels of stakeholders including eleven technical working groups, business organizations, private sector players, and international development partners which contributed to the development of the plan. The NIIMP was also validated at the national and subnational levels with the aim of providing critical infrastructure for the country. In comparison, the Water Sector Road Map (2011), which featured all the levels of government as critical stakeholders in the plan, tasked with planning and implementing several water schemes across the country. Multilateral agencies and organizations were identified as potential funders. However, the plan did not specify the level of involvement of the stakeholders in developing and implementing the plan.

Changes in political regimes could impact the viability of a policy, and this is a common occurrence in Nigeria (Obamwonyi & Aibieyi, 2014). Again, the NUDP reflects a classic example where at the time of publication, the chief ministry responsible for the policy was the Federal Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development which originally assigned the task of urban development in the NUDP. It is important to note that the NUDP had a 2020 outlook. However, successive administration has scrapped the ministry, and at best, the Federal Ministry of Works and Housing and the Ministry of Environment are probable remnants of the earlier ministry involved in this policy, raising questions on the sustainability of the visions postulated therein.

The involvement of apex executive offices of the president/vice president at the executive council in the Agricultural Transformation Agenda (2011) suggests serious commitment to see the manifestation of the goals in the agenda. The Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development is a key stakeholder alongside critical units and agencies (e.g., fertilizer department) in the coordination and implementation of the agenda. Other stakeholders identified within the agenda included state governments, the ministries of communication, the CBN, mobile network operators, NAFDAC, and donor agencies. The interconnectedness of the sectors identified had the potentials of driving progress. However, the availability and adoption of modern agricultural technologies were identified within the agenda to be a critical weak point.

Some policies evaluated factors that could impact stakeholders and their potentials of benefitting from the policy. In the Agriculture Promotion Policy, key stakeholders recognized included farmer associations, cooperatives, NGOs, CBOs, CSOs, development partners, and the private sector. The federal government is alluded within the APP to provide the enabling environment for these stakeholders to thrive. Some generic threats that could impact stakeholders were identified within the APP document to include inconsistency of governance regimes, policies, legislation and financial mechanisms, lack of cooperation and synergy among key MDAs and stakeholders, absence of a comprehensive soil map for Nigeria, lack of access to alternative energy use and poor infrastructure to support smart agriculture, lack of quality control standard, and no single point of contact, making it difficult for investors to find available services. The lack of awareness among farmers leads to inadequate use of agro-chemicals leading to food contamination and poor yield. The private sector was identified to have low investment in agriculture and agro-processing. Yet, government services were noted to be frequently delayed, and contracts and MOUs with government parastatals go unfulfilled.

Some policies were not specific about where funding for the policy initiatives will come from. Multiple stakeholders were involved in the National Policy on Food and Nutrition, which could be considered an advantage in program design and implementation as well as resource mobilization. This also implies that costs will be shared across the different stakeholders identified above, which will ensure a sense of ownership and sustainability. However, the nature of the various stakeholders (federal agencies and parastatals and NGOs) means that funding is also problematic as the policy was not specific about how much funding will be coming from the identified stakeholders. Additionally, failure to secure community involvement was also considered to be a potential weakness to the policy. Poor funding as well as failure to properly involve community stakeholders at the program implementation level is considered a weakness.

We observed that programs that were funded by development partners had some advantages as they had ready funding, had less political interference, were strictly monitored, and had a division of labor. The NURHI is a key instance as it was driven by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (major financer), John Hopkins Center for Communication Programs (JHCCP), Association for Reproductive and Family Health (ARFH), and Centre for Communication Programs Nigeria (CCPN). The strategies used to drive the program were community-driven (NUHRI, n.d-a). The program was operational in Ibadan, Abuja, Ilorin, Kaduna, Benin, and Lagos. NURHI has four core partners: Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Communication Programs (CCP); John Snow, Inc. (JSI); the Nigerian Association for Reproductive and Family Health (ARFH); and the Center for Communication Programs Nigeria (CCPN). Other contributing partners include Development Communications Network (DEVCOMS); Advocacy Nigeria; Planned Parenthood Federation of Nigeria (PPFN); Health Reform Foundation of Nigeria (HERFON); the Futures Institute; and National Family Planning Action Group (FPAG) at the national level. While Center for Communication Programs (CCP), as the prime contractor, has the overall financial and programmatic responsibility for the NURHI, John Snow, Inc. (JSI) and the Nigerian Association for Reproductive and Family Health (ARFH) supported improvements in the supply of reproductive health services. CCP and Center for Communication Programs Nigeria (CCPN) facilitate increases in the demand for reproductive health and advocacy initiatives. Other agencies, projects, and private companies contribute technical expertise in their respective areas and/or undertake specific scopes of work. The strengths of the stakeholders include the availability of resources, less political interference, availability of research evidence on maternal health informed the program, and the prioritization of implementation sites. The NURHI was a robust initiative as it passed through all the stages of approval in the national policy making process, despite delays. However, there was an absence of counterpart funding and bureaucratic bottlenecks from Nigerian governments — national, state, and LGA, which constituted a problem towards the effective implementation of the policy.

The strength of the current NHGSFP is that states are not forced to participate. They choose to participate following assessment of their resources to match provisions of the federal government. However, with no legal backing for statutory allocations, subsequent administrations could discontinue the program as the abandonment of policies and programs are characteristic of past Nigerian government regimes.

Role of Evidence in Urban Development Policies in Nigeria

Various forms of evidence were stated to have been used in the development of some of the urban development policies. The types of evidence used include (i) review of achievements (or lack thereof) of past public responses and interventions (including policies and plans) in urban development; (ii) learnings and lessons from other country experiences; (iii) successes or failures recorded by previous and existing national policies and plans; (iv) situation analysis reports of coverage of services (related to specific policies); (v) findings from document and literature review on high-impact interventions/strategies and potential benefits to the country/sector; (vi) theoretical knowledge; and (vii) prospective evaluation/review of investment needs and outcomes. Data on high-impact interventions were also stated to have been used in refining priority areas within some policies. It is characteristic of many documents to present development statistics and economic analysis of the country. Sometimes, the performance of different geopolitical zones in the county in certain indices of development is featured (e.g., Making Nigeria Open-Defecation-Free by 2025) as evidence for policy and development needs. Table 5 highlights the role of evidence in formulating other urban development policies in Nigeria.

Specific examples of how evidence was used in urban policy development include that (i) a brief review of achievements of past public responses and interventions and their achievements (or lack thereof) informed the development of the NUDP 2012; (ii) the weaknesses of past housing/infrastructure schemes/policy across different phases of Nigeria’s development were reviewed and lessons were drawn to inform the NHP 2012; (iii) the NIRP 2014 was developed using learnings from country experiences in industrialization — such as China, Brazil, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and South Korea; (iv) the NIIMP 2015 took stock of existing infrastructure and identified the required investments (based on sector growth strategies, outcome targets, and international benchmarks) to bring infrastructure in line with the country's growth aspirations; and (v) data on access to water and sanitation informed the design of Nigeria Water Sector Road Map 2011.

The Agricultural Transformation Agenda (2011) appear to have been developed using robust evidence. These included an account of the performance of the sector (agricultural productivity) and international trade (food importation and exportation) over years; lessons from other countries that have succeeded in improving and maintaining high agricultural production per capita through agricultural transformation initiatives; and theoretical knowledge from Theory of Agricultural Export Restrictions to ensure food security.

Discussion

The Nigerian urban policy landscape can be understood to be advancing, as more recent policy documents are more sophisticated than older ones. The recognition of the roles of stakeholders and evidence is improving as recent policy documents are more deliberate and explicit about both evidence and stakeholder involvement compared to older policy documents. More recent policies are also beginning to go beyond generic mentions of ‘government’ to identifying specific stakeholders participation in policy formulation as well as specific functions assigned to stakeholders. Yet, there is still room for more policy exactness. Although there is often identification of multiple stakeholders in the policy documents, the roles of stakeholders in developing the policy are often vague. Only very few policies/plans/strategies specified who the stakeholders were (e.g., MNOPF), and the process with which they were engaged (e.g., NURHI). The offices and/or persons expected to take specific actions in policy initiatives are often missing. Identifying and engaging senior responsible officers who would take charge and would be accountable for the day-to-day running of aspects of the policies are critical to the success of policy initiatives (Commonwealth of Australia, 2014). A clear definition of specific actors and roles within policies is expected to improve accountability and legitimacy of the actor (Blum & Reinecke, 2017). Fitting the right actor in a specific role in policy initiatives is indeed important for policy progress and action. One way to achieve action is by adopting a critical stakeholder analysis which should examine the interest, position, and power/influence of different stakeholders (Gilson et al., 2012). Balane et al. (2020) have described a stakeholder analysis framework that can help understand stakeholders’ knowledge, interest, power, and position as well help reduce ambiguity in how stakeholders are weighed. Though the Balane et al. (2020) stakeholder analysis framework is designed for health policies, it could be a good guide in approaching urban policy formulation and implementation.

The use of evidence to inform Nigerian urban policies is also increasingly getting better. Evidence were often pulled from reviews of past policies and the political environment, progress, and setbacks experienced so far, as well as professional opinions. Statistical data from local and international organizations also formed the basis of the evidence informing policies. However, the tone of policies is often not rooted in evidence. Policy documents reviewed often tend to have a declarative tone, and this makes it difficult to see objectivity in the some policy documents (Onwujekwe et al, 2021a).

It should however be noted that the improvements seen across policies in the policy documents does not necessarily equate policy effectiveness. Separate studies/analysis as well as monitoring and evaluation would be needed to determine if recent improvements in the structures of policies imply better implementation and effectiveness. Even though most policy documents identify connected stakeholders alongside their expected roles, there is little conviction within most policy documents that these actors will rise to the occasion to pursue the implementation of these policies. Monitoring and evaluation arms of the policy documents are often not convincing. The evaluative report on the NSPFS stands out as a policy/program that was robustly assessed for its impact. The strengths and limitations of the NSPFS were featured, and key lessons and recommendations were given. However, assessment for impact or monitoring a policy is not useful if the lessons are not utilized to improve the intervention (Fretheim et al., 2009). One review of urban-focused policies in Nigeria reported that social inclusivity and equitable access to health are poorly addressed in Nigerian policy documents (Onwujekwe et al., 2021b).

Evaluative culture within Nigerian policy documents is rare. Evidence of effectiveness was barely perceptible in most of the policy documents. At best, the reviewed policy documents often highlighted the weaknesses of previous policies, especially with regard to areas not covered and the current global/national trends. These critics are often the bases for a “new” policy. Again, policy documents were generic and barely discussed program/policies with specific reference to urban places. However, one evaluative document stands out. The document on the NSPFS stood out as a comprehensive document that assessed a federal government program. The evaluative document on the NSPFS identified specific areas where the policy/program proved effective and where there are loopholes. Urban areas as well as peri-urban and rural places were all covered by the NSPFS. The evaluative report on the NSPFS indicated that food production increased, and the benefits were felt in households, more so vulnerable and disadvantaged homes. Education and awareness campaigns also carried health knowledge to the sites covered in the study. Also, equipment and facilities were reported to be supplied to health centers in the areas covered by the NSPFS.

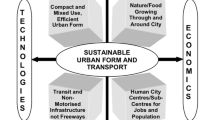

Apart from policies that were specifically designed for urban areas (e.g., the National Urban Development Policy), other policy documents, which may highlight urban areas/spaces as being inclusive in its coverage, lack detailed coverage of urban needs. Details of consideration for urban areas in these policies are almost always superficial, and stakeholders are rarely engaged with the urban needs in focus. The need for urban-focused policies is even more important in contemporary times when Nigeria is among the countries set to experience a vast increase in the number of urban dwellers (UN-Habitat, 2016). There is a need for an integrative approach in policy formulation process in Nigeria. Building sustainable Nigerian cities require an integrative approach rather than addressing issues in isolation, such that local resources are harnessed in addressing diverse urban needs in a sustainable way (Sustainable Development in the Twenty-First Century [SD21], 2016). Hence, policies across sectors should have a reflection on urban needs and proffer initiatives that address the challenges and peculiarities of urban places.

Grass root stakeholders do not appear to be given much consideration in the development and implementation of urban sustainability policies. The different levels of government, federal ministries, and their aligning departments, agencies, and units dominantly feature across policies. Also community-level players including CSOs, CBOs, NGOS, business organizations, and professional regulatory agencies also feature in urban-related policies as stakeholders. However, the tone of policy documents often appears declarative, and the contributory voices of stakeholders are often not perceived. Perhaps, the lack of a common policy development framework guiding the policy development process contributes to the omission of the grass root stakeholders. As such, stakeholders at the community levels should be incorporated in the planning, development, and implementation of sustainable urban policies. Stakeholders like WDC were mentioned in the National Health Policy, but their participation in the process was poorly defined. They were tasked with the role of promoting healthcare in their respective wards. Meanwhile, achieving sustainable urban development requires that stakeholders participate in urban policies that promote social inclusion (UN-Habitat, 2016). The private sector and particularly the organized private sector were identified to be key in achieving the takeoff of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Nigeria (Onoka et al., 2015). There is thus a need to increase awareness among policy makers on the importance of acknowledging the urbanization challenge facing Nigeria and the need to have it in focus across policies.

Policy Implications

Some of the policy implications of the findings are that multi-sectoral collaboration in developing urban policies and plans is required so that there is social inclusion and critical areas of wellbeing of urban dwellers such as health and nutrition are well covered in the policies and plans. Another policy implication is the need to resolve the factors that have constrained implementation of national policies and plans on urban development in Nigeria, which include among others the inadequate technical capacity, human resources for evidence-based planning, and fiscal autonomy of subnational governments for urban planning. Other constraining reasons that should be resolved for better planning and implementation of policies and plans are the inadequate integration of relevant stakeholders in policy development and implementation process; the duplication of authority at the state level, with some stakeholders roles overlapping which could result in duplication, shirking, and weak/poor accountability for actions/inactions; and lack of clarity of roles of stakeholders in urban development.

The role of evidence and stakeholders can be more systematically deployed within policies. Evidence-based initiatives and an assessment of stakeholder power and alignment are likely ingredients that can spur action towards the desired change. Uzochukwu et al. (2016) found that collaboration between researchers and policy makers to be a critical strategy in imbuing evidence into policies. Thus, policy makers are likely to use research evidence which they contributed in generating. Thus, building alignments between policy makers and researchers, which can be facilitated by strong research groups (see Uzochukwu et al., 2016), can be an important step towards policy improvement in Nigeria and the African region.

Limitations

Although we deployed a systematic way of identifying policy documents and research articles, our findings may not be an exhaustive description of the urban policy landscape. Indeed policies that captured health and nutrition concerns were examined. Most of the documents reviewed were national-level policy documents. Again, we only deployed a desk review in evaluating policy documents, and this may limit the quality and depth of our findings. Interviews and/or survey studies can add depth to the issues identified and highlight the lived experiences of people in urban places in Nigeria. Future studies could explore other research approach to studying the impact of health and nutrition policies.

Conclusion

The urban population is growing rapidly in Nigeria and indeed many developing countries. Access to food and adequate health care are important concerns to ensure the health and wellbeing of the population. Adequate urban-focused policies are important to ensure that urban settings are sustainably managed. Policies that ensure a robust inclusion of stakeholders and a strong consideration of evidence can help to drive sustainable growth and achievements in urban settings. In this review of urban policies that have focused on health and food/nutrition, we found that consideration of stakeholders and evidence in the formulation and implementation of Nigerian urban policies seems to be given shallow thought. However, the general policy landscape can be considered to be improving as recent policy documents are more sophisticated and are deliberate about involvement of stakeholders and the use of evidence.

Researchers, concerned stakeholders, city leaders, and policy champions have an urgent need to strongly advocate using evidence to the politicians and top government officials on the need for evidence-based and multi-sectoral development and implementation of policies and plans for sustainable and inclusive urban development. Weak stakeholders’ involvement and lack of evidence-based policy could jeopardize the policy process. Government, policy makers, and urban planners should recognize the importance of stakeholders and evidence-based policies as key to urban sustainability.

Policies and plans are often not specific of the participatory contributions of these stakeholders in policy development and initiative generation. Perhaps, the lack of a precise and harmonious policy development framework for the country contributes to the non-systematic approach for stakeholders’ contribution. Apart from programs or initiatives funded by development partners, the confidence that government across federal, state, and local levels will commit to funding/implementing evidence is low. The lack of precision on which actor is responsible for specific roles within policies showcases a serious gap across policies which can stall policy implementation.

Availability of Data and Material

None.

Code Availability

None.

References

Adama, O. (2020). Slum upgrading in the era of world-class city construction: The case of Lagos, Nigeria. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 12(2), 219–235.

allAfrica. (2020). Nigeria: COVID-19 – Only 169 ventilators in 16 states. Available at: https://allafrica.com/stories/202004010571.html. Accessed Apr 1, 2020.

Balane, M. A., Palafox, B., Palileo-Villanueva, L. M., McKee, M., & Balabanova, D. (2020). Enhancing the use of stakeholder analysis for policy implementation research: Towards a novel framing and operationalised measures. BMJ Global Health, 5(11), e002661. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002661

Barry, M. J., & Edgman-Levitan, S. (2012). Shared decision making—The pinnacle patient-centered care. The New England Journal of Medicine, 366(9), 780–781.

Blum, M., & Reinecke, S. (2017). Towards a role-oriented governance approach: Insights from eight forest climate initiatives. Forests, 8(3), 65.

Bolaji, S. D., Gray, J. R., & Campbell-Evans, G. (2015). Why do policies fail in Nigeria. Journal of Education & Social Policy, 2(5), 57–66.

Cheung, K. K., Mirzaei, M., & Leeder, S. (2010). Health policy analysis: A tool to evaluate in policy documents the alignment between policy statements and intended outcomes. Australian Health Review, 34(4), 405–413.

Davies, P. (2004). Is evidence-based government possible. Jerry Lee Lecture, 19.

Essen, C. (2019). FG plans new national urban development policy. The Guardian, Retrieved from https://guardian.ng/property/fg-plans-new-national-urban-development-policy/. Accessed 2 Aug 2020.

Evidence-based policymaking collaborative. (2016). https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99739/principles_of_evidence-based_policymaking.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2021.

Farrell, K. (2018). An inquiry into the nature and causes of Nigeria’s rapid urban transition. In Urban Forum, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 277-298. Springer Netherlands

Federal Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development. (2012). National Housing Policy.

Federal Ministry of Lands, Housing and Urban Development. (2012). National Urban Development Policy.

Federal Republic of Nigeria. (2012a). National urban development policy. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Land, Housing and Urban Development.

Federal Republic of Nigeria. (2012b). National housing policy. Federal Ministry of Works and Housing.

Freire, M. E., Hoornweg, D., Slack, E., & Stren, R. (2016). Inclusive growth in cities: Challenges & opportunities. Corporación Andina de Fomento.

Fretheim, A., Oxman, A. D., Lavis, J. N., & Lewin, S. (2009). SUPPORT tools for evidence-informed policymaking in health 18: Planning monitoring and evaluation of policies. Health Research Policy and Systems, 7(1), 1–8.

Gilson, L., Erasmus, E., Borghi, J., Macha, J., Kamuzora, P., & Mtei, G. (2012). Using stakeholder analysis to support moves towards universal coverage: Lessons from the SHIELD project. Health Policy and Planning, 27(suppl_1), i64–i76.

Global Nutrition Report. (2020). Nigeria nutrition profile: Country overview-Malnutrition. https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/western-africa/nigeria/. Accessed 2 Feb 2021.

Nzeadibe, T. C., & Anyadike, R. N. C. (2012). Social participation in city governance and urban livelihoods: Constraints to the informal recycling economy in Aba, Nigeria. City, Culture and Society, 3(4), 313–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2012.10.001

Obadan, M. I., & Uga, E. O. (2017). Think tanks in Nigeria. In Think tanks and civil societies, pp. 509–528. Routledge.

Obamwonyi, S. E., & Aibieyi, S. (2014). Public policy failures in Nigeria: Pathway to underdevelopment. Public Policy and Administration Research, 4(9), 38–44.

OECD Regional Development Ministerial. (2019). Megatrends: Building better futures for regions, cities and rural areas. https://www.oecd.org/regional/ministerial/documents/urban-rural-Principles.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2020.

Oguntoyinbo, O. O. (2012). Informal waste management system in Nigeria and barriers to an inclusive modern waste management system: A review. Public Health, 126, 441–447.

Okoroma, N. S. (2006). Educational policies and problems of implementation in Nigeria. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 46(2), 243–263.

Olomola, A. (2007). An analysis of the research-policy nexus in Nigeria. In E.T Ayuk & M.A. Marouani (Eds.) The Policy paradox in Africa–Strengthening links between economic research and policymaking. (1st ed. pp. 165–184). African World Press, IDRC.

Onoka, C. A., Hanson, K., & Hanefeld, J. (2015). Towards universal coverage: A policy analysis of the development of the National Health Insurance Scheme in Nigeria. Health Policy and Planning, 30(9), 1105–1117.

Onwujekwe, O., Uguru, N., Russo, G., Etiaba, E., Mbachu, C., Mirzoev, T., & Uzochukwu, B. (2015). Role and use of evidence in policymaking: An analysis of case studies from the health sector in Nigeria. Health Research Policy and Systems, 13(1), 46.

Onwujekwe, O., Agwu, P., Onuh, J., Uzochukwu, B., Ajaero, C., Mbachu, C., … & Mirzoev, T. (2021). An analysis of urban policies and strategies on health and nutrition in Nigeria. Urban Research & Practice, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2021.1976263

Onwujekwe, O., Mbachu, C. O., Ajaero, C., Uzochukwu, B., Agwu, P., Onuh, J., … & Mirzoev, T. (2021). Analysis of equity and social inclusiveness of national urban development policies and strategies through the lenses of health and nutrition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 1-10

Orjiakor, C. T., Weierstall, R., Bowes, N., Eze, J. E., Ibeagha, P. N., & Obi, P. C. (2020). Appetitive aggression in offending youths: Contributions of callous unemotional traits and violent cognitive patterns. Current Psychology, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00759-4

Popoola, O. O. (2016). Actors in decision making and policy process. Global Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 5(1), 47–51.

Rütten, A., Lüschen, G., von Lengerke, T., Abel, T., Kannas, L., Diaz, J. A. R., … & van der Zee, J. (2003). Determinants of health policy impact: A theoretical framework for policy analysis. Sozial-und Präventivmedizin/Social and Preventive Medicine, 48(5), 293-300

Saidu, A. I., & Yeom, C. (2020). Success criteria evaluation for a sustainable and affordable housing model: A case for improving household welfare in Nigeria cities. Sustainability, 12(2), 656.

Sutcliffe, S. (2005). Evidence-based policymaking: What is it? How does it work? What relevance for developing countries?. No. Folleto 1427. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/3683.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2021.

The World Bank. (2019). Urban population growth (annual %) – Nigeria. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.GROW?end=2017&locations=NG&start=1960. Accessed 18 June 2020.

Trading Economics. (2020). Nigeria. Retrieved from https://tradingeconomics.com/nigeria/news. Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

UN Habitat. (2015). Habitat country programme document Nigeria: 2015–2017. Retrieved from https://mirror.unhabitat.org/downloads/docs/13237_1_595875.pdf. Accessed 13 Dec 2020.

UNAIDS. (2020). Nigeria. Retrieved from https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/nigeria. Accessed 2 Feb 2021.

UN-Habitat. (2016). National urban policies. Habitat-III Policy Papers. http://uploads.habitat3.org/hb3/Habitat%20III%20Policy%20Paper%203.pdf. Accessed 13 Jan 2021.

Usman, S. (2010). Planning and national development. In S. O. Akande & A. J. Kumuyi (Eds.), Nigeria at 50 – Accomplishments, challenges and prospects (pp. 710–724). NISER Research Seminar Series (NISER).

Uzochukwu, B., Onwujekwe, O., Mbachu, C., Okwuosa, C., Etiaba, E., Nyström, M. E., & Gilson, L. (2016). The challenge of bridging the gap between researchers and policy makers: Experiences of a Health Policy Research Group in engaging policy makers to support evidence informed policy making in Nigeria. Globalization and Health, 12(1), 67.

Varrella, S. (2021). Health insurance coverage in Nigeria 2018, by type and gender. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1124773/health-insurance-coverage-in-nigeria-by-type-and-gender/#statisticContainer. Accessed 8 Sep 2021.

Von Wright, G. H. (1976). Determinism and the study of man. In Essays on explanation and understanding (pp. 415–435). Springer.

World Bank. (2006). Nigeria - Lagos Metropolitan Development and Governance Project. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2006/06/6864622/nigeria-lagos-metropolitandevelopmentgovernance-project

World Health Organization. (2018a). World malaria report, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2018/en/. Accessed 8 Apr 2020.

World Health Organization. (2018b). World Health Organization - Noncommunicable diseases (NCD) country profiles, 2018: Nigeria. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/nmh/countries/nga_en.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2021.

Yagboyaju, D. A. (2019). Deploying evidence-based research for socio-economic development policies in Nigeria. Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, 7(1), 1–9.

Funding

The research reported in this paper was supported by the Research England through the QR GCRF, grant number 95598105.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Obinna Onwujekwe, Benjamin Uzochukwu, and Tolib Mirzoev contributed to the study conception and design. All authors participated in the material preparation, data collection, and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Obinna Onwujekwe and Charles Orjiakor, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not required.

Consent to Participate

None required.

Consent for Publication

None required.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The views are of the authors only.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Onwujekwe, O., Orjiakor, C.T., Odii, A. et al. Examining the Roles of Stakeholders and Evidence in Policymaking for Inclusive Urban Development in Nigeria: Findings from a Policy Analysis. Urban Forum 33, 505–535 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-021-09453-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-021-09453-5