Abstract

Part of a larger project aimed at performing an empirical meta-theoretical analysis of the entire corpus of scientific literature on Social Representations Theory (SRT), this research presents the state of the art of the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT. Applying the Grid for Meta-Theoretical Analysis on 295 publications selected from the So.Re.Com“A.S. de Rosa”@-library, we compiled a rich set of meta-data and data illustrative of how SRT was conceptualized and operationalized within the anthropological and ethnographic approaches, as well as its positioning among other theoretical and disciplinary frameworks. The data was submitted to textual analysis, followed by a Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components analysis. The empirical results suggest that from a theoretical standpoint, the anthropological and ethnographic approaches - inspired by its main exponents Jodelet (1991, 2016) and Duveen and Lloyd, (1986, 1993) - are consistent with the dynamic conceptualization of social representations set out by Moscovici (1961/1976, 1984/2003, 1988, 2000, 2013), as revolutionary paradigm that has shifted the emphasis of social psychology from looking at isolated variables in individuals in the abstract, towards a supra-disciplinary integrative vision of a social science, that investigates the genesis, transformation and negotiation of social representations in the communicative actual contexts (Billig 1991; de Rosa 2013a, b; Sammut et al. 2015a). From an empirical perspective, the variety of qualitative methods employed were open to investigate socio-cultural dimensions and symbolic universes, reflecting the integrative tradition of SRT that bridges diverse neighbouring disciplines in an effort towards a multifaceted perspective on the object of study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 1961, Moscovici proposed through his doctoral thesis, La psychanalyse, son image et son public, a new perspective in social psychology, elaborated in the Social Representations Theory (SRT), which aims to cross the traditional disciplinary boundaries from psychology, sociology, anthropology, communication studies with the purpose of comprehensively explaining the influence of the social on how people co-construct knowledge in representations through interaction and communication and, respectively, how the representations influence their lives (Moscovici 1961/1976).

Over time, different perspectives on SRT emerged, all claiming a strong affiliation to the initial theory, that has become a sort of supra-disciplinary field (de Rosa 2013a) characterised by a great consistency in terms of paradigmatic and theoretical inspiration ensuring at the same time a great diversity with regard the thematic areas of study (science and social representations, education, health, politics, environment, economics, communication and media, marketing and organisational contexts, collective memories, identities, gender, etc. de Rosa et al. 2016a, 2018a), in terms of methodological approaches and epistemological options (descriptive, qualitative, monographic, anthropological, ethnographic, conversational, discursive, experimental, structural, multi-methodological, etc.) and with respect to the applied contexts and domains of expert and lay knowledge production and transmission (Jodelet 2013). According to de Rosa (2013a, b), five main approaches to SRT can be identified in the way the scientific literature produced worldwide in almost 60 years theory has approached SRT in empirical researches: the structural approach, the socio-dynamic approach, the anthropological and ethnographic approaches, the narrative approach and dialogical approaches and the latest proposed as modelling approach. The differences among them reflect the ontological and epistemological concerns unfolding at the time of the theory’s inception, concerns residing in the distinctiveness of the SRT’s socio-constructionist perspective (Guareschi 2000) from other more popular scientific trends in social sciences, namely social cognition (de Rosa 1992; Wagner 1996) and even from the most radical version of the discursive analysis (de Rosa 2003, 2006). More recently, several authors tend to underline points of convergence between these perspectives (e.g. Emiliani and Passini 2017; Rateau et al. 2011; Rateau and Lo Monaco 2013; Flick et al. 2015).

In line with the eclectic vision of methodological polytheism legitimated by Moscovici (Moscovici and Buschini 2003) and practiced in his research (including field studies, media studies and laboratory-based experimental studies), de Rosa in her integrative vision of the modelling approach (de Rosa 2013a, b, 2014a) promotes a multi-theoretical and multi-method approach where the articulation-differentiation of various constructs and related paradigm (attitudes, opinions, beliefs, common sense, images, social and collective memory, multi-dimensional identities, emotions, symbolic meanings, actions and practices, stereotypes...) need to be epistemologically justified on the basis of their epistemic principles’ compatibility and empirically modelled. Well beyond the traditional conception of multi-methods as sum of mixed techniques and adoption of triangulation (Flick et al. 2015), the modelling approach requires research designs guided by specific hypotheses also concerning the interaction between expected results and methods (including multiple techniques - based on different communicative channels, not restricted to verbal and textual channels, but also iconic, behavioural and other symbolic systems - and various data analysis strategies). The modelling approach may be also a route for unifying the above-mentioned approaches - developed to operationalize the SRT in empirical designs also referring to neighbour disciplines (such as anthropology, sociology, ethnography, communication studies, cultural studies, semeiotics etc.) - in an integrated framework, that would greatly enrich the theoretical and empirical versatility of SRT.

Starting from the premise that the study here presented focuses on the ethnographic and anthropological methodological orientations within the social representations literature, the wider research program also investigates the genesis and development of other approaches (structural approach, socio-dynamic genetic approach, dialogical, conversational, narrative, discursive approaches, modelling approach…) inspired by the social representation theory. The authors’ intention is not to establish a hierarchy of priorities or superiority of the models in circulation (all legitimate to exist and to be chosen according to the author’s intellectual choices), but to illustrate in this article the dissemination of the ethnographic and anthropological approaches through an empirical meta-theoretical analysis. The reference to the “modelling approach” (the latest defined in the literature and therefore also the least diffused) is to stress its distinctive feature, that allows the potential integration, rather than the opposition of the other approachesFootnote 1 coherently with the complexity of the supra-disciplinary view of the Social Representation Theory and all unified by its vision of the relations between scientific and laypeople knowledge and its dynamic in society through inter-individual, intergroup, institutional and media communication.

Despite differences between the aforementioned taxonomies, whether conceived as an approach or as one of the most optimal research methods specific to the study of SRs (e.g. Bauer and Gaskell 1999; Wagner et al. 1999), there is little disagreement over the important contribution of the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to the developments of SRT (Sperber 1989, 1990), mainly due to the compatibilities with Moscovici’s conceptualizations, as pointed out by Wagner: “It is perhaps a little surprising that ethnography has not been more widely used in the study of social representations. Indeed, in spite of Moscovici’s explicit definition of social representations as ‘system(s) of values, ideas and practices’ (1973, p.xiii), the theme of practice has been relatively neglected, although Jodelet’s (1991) study is an exception” (Wagner et al. 1999).

Our paper focuses on the literature inspired by anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT, in order to shed some light on its theoretical and methodological articulations and coherence with the original conceptualization of SRT through a systematic meta-theoretical analysis (de Rosa 2013b). The empirical Meta-theoretical Analysis is not the classical Meta-analysis, widely used especially in medicine (Normand 1999), but also in social sciences, using “secondary analysis to the re-analysis of data for the purpose of answering the original research question with better statistical techniques, or answering new questions with old data (….) “Meta-analysis refers to the analysis of analysis” using “the statistical analysis of a large collection of analysis results from individual studies for the purpose of integrating the findings. It connotes a rigorous alternative to the casual, narrative discussions of research studies which typify our attempts to make sense of the rapidly expanding research literature” (Glass, G. Glass 1976: 3).

The main nine steps to classical Meta Analyses include:

-

1.

Frame a question (based on a theory)

-

2.

Run a search (on Pubmed/Medline, Google Scholar, other sources)

-

3.

Read the abstract and title of the individual papers.

-

4.

Abstract information from the selected set of final articles.

-

5.

Determine the quality of the information in these articles. This is done using a judgment of their internal validity but also using the GRADE criteria

-

6.

Determine the extent to which these articles are heterogeneous

-

7.

Estimate the summary effect size in the form of Odds Ratio and using both fixed and random effects models and construct a forest plot

-

8.

Determine the extent to which these articles have publication bias and run a funnel plot

-

9.

Conduct subgroup analyses and meta regression to test if there are subsets of research that capture the summary effects

Although in principle both approaches may share the interest of conducting empirical systematic analysis of many studies, the scope of the Meta-theoretical approach originally developed since 1994 (see de Rosa’s references in the biblio: de Rosa 1994, 2002, 2014b; de Rosa et al. 2015; de Rosa 2016a, 2019a, b) is much wider than “to arrive at evidence synthesis” of empirical results of previous studies based on abstract information and some statistical applications, but to empirically and systematically investigate the development of the theory worldwide across different geo-cultural contexts and over the multiple generations of scientists working on several thematic areas. Therefore the entire texts (and not only the abstracts) are object of a very detailed analysis from the theoretical perspective, both with Reference to theoretical constructs specific of Social Representations Theory in its original formulation and development through different paradigmatic approaches and with Reference to other theoretical constructs and/or theories and to different disciplinary approaches in social sciences (anthropological, developmental, ethnographic, ethogenic, philosophical, psychodynamic, sociological…); from the Thematic Analysis of different research areas and their specific objects of study; from the Methodological Profile of the study and finally from the Paradigmatic Implications. The wider research program “For a biography of a theory” (de Rosa 2019a, b) interested in the interplay between several sources and channels (the publications as textual sources, the narratives of scientists and their networking activities through conferences and training events) also integrates the analysis of the publications (as source of reified knowledge) with the interviews with the multi-generational protagonists of the scientific field “Between the biography of a theory and the intellectual auto-biography of scientists” and the analysis of the whole series of dedicated scientific events.Footnote 2

The study here presented is therefore included in an ample research project addressing the empirical meta-theoretical analysis of the entire corpus of publications employing SRT, initiated by de Rosa in 1994 and object of a European Commission approved and funded PhD program during 2013–2017 (de Rosa 2016b). This unified research program has been articulated according to three main directions: the diffusion and anchoring of the scientific production into various geo-cultural contexts, the multiple thematic orientations and, respectively, the diversified paradigmatic approaches. Coherently with the purpose of this paper, we will search empirically based answers to our research questions:

-

a.

How did this approach develop over time and across geo-cultural contexts?

-

b.

What characterizes the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT from a conceptual and methodological perspective?

-

c.

What are the main thematic areas explored within this approach?

Previous results from the meta-theoretical analysis show empirical evidence of the general trends in the development of SRT (e.g.; de Rosa 2002, 2011, 2013b, 2015, 2016a, 2019a, 2019b), its dissemination across the world and its impact in the bibliometric area also trough the networking activities (de Rosa 2015, 2016a; de Rosa 1992–2020; de Rosa 2019a, b; de Rosa et al. 2015, 2018a, b, c; de Rosa 2019a, b), as well as the role played by the organization of the dedicated series of biannual international conferences ICSR-International Conferences on Social Representations (de Rosa and d’Ambrosio 2008; de Rosa 2019b).

These previous findings revealed that – after a latency period of almost 20 years - the theory has expanded from France to all the geo-cultural spaces (Europe, Latin America, North America, Australia & New Zealand, Asia and Africa), albeit with some differences, in the sense that most of the publications are still from Europe (the theory’s homeland) and Latin America (the cross-fertilized scenario), followed by North America and the others new emerging scenarios in Asia and Africa (de Rosa 2008, 2016a; 1992–2020; de Rosa 2019a, b; de Rosa et al. 2015, 2017, 2018a, b, c, 2019a, b).

From a temporal perspective, de Rosa found that the scientific production on SRT is following an upward trend, while from the paradigmatic perspective, the structural approach started to be less dominant parallel to the increasing popularity of the other approaches and to the emergence of new ones, such as the narrative (Laszlo 1997; Purkhardt 2002), dialogical (Markova 2003) approaches (see de Rosa 2002, 2013b). These investigations were conducted on the entire production of scientific literature on SRT filed in the SoReCom ‘A.S. de Rosa’ @-library (de Rosa 2014b, 2015, 2018) that is subject to continuous improvement both from the technological and scientific contents perspectives. From the perspective of one of his main intellectual interests - centred on the history of science - Moscovici has recognised as the main value of de Rosa’s invention of the Meta-theoretical Analysis (that “is not” a classical meta-analysis, as above mentioned): to chart “the progression of a specific theory useful for advancing knowledge,” and “the utility of studying the theory’s epidemiology”. He suggested many times the interest to achieve a patent for having designed the research tools implemented in the SoReCom A.S. de Rosa @-library, because he was convinced that - just changing its contents designed for meta-theoretically analysing the specific Social Representation theory - the tool could be useful to meta-theoretically analysis and mapping the epidemiology of other theories, even in other disciplinary fields, not restricted to social sciences. (see the autograph document of Moscovici cited in de Rosa 2019a, For a biography of a theory).

Up to date, to our knowledge, there has been no study dedicated to specifically meta-theoretically analyse the scientific data on the anthropological and ethnographic paradigmatic approaches, an issue that our paper aims to address.

Method

Instruments

Although the wider research program aimed at the illustrating the ‘biography of the SR theory’ (de Rosa 2019a, b) integrates diverse methodologies, the main research tool used for this contribution is the Grid for Meta-Theoretical Analysis. It was created in 1994 by de Rosa, updated in February 2014 (as far it concerns the version used at the time of building data and meta-data for this article, although later it has been further improved, last version: March 2020) and inserted in the most comprehensive repository specialized in Social Representation currently available worldwide SoReCom ‘A.S. de Rosa’ @-library (de Rosa 2014b, 2015, 2018) as a research web-tool linked to a special search engine to retrieve and cross data and meta-data produced by each field of the Grid (de Rosa 2014b, 2018). The Grid was specifically designed as a systematic analysis tool to be applied on the scientific literature dealing with SRT in order to grasp not only the traditional set of information concerning bibliographic and bibliometric elements linked to each publication (author/s, institutional affiliation, country and continents, year of publications, title of the article or book chapter or book, or conference presentation etc. - depending of the resource type - Journal, publisher, location, bibliometric indexes, etc.), but more specifically to detect how the S.R. theory was employed in the literature from a meta-theoretical perspective. The procedure for conducting meta-theoretical analyses consists in reading each publication and systematically detecting whether the categories and a rich list of modalities organized around 5 main sections present in the Grid may be found in the respective paper:

-

(1)

References to Constructs/Concepts Specifically Related to SRT

-

(2)

References to Constructs/Concepts Pertaining to Other Theories and Disciplinary Approaches

-

(3)

thematic areas (and specific objects of study);

-

(4)

methodological profile,

-

(5)

paradigmatic implications

(for a comprehensive description of the Grid, see de Rosa 2002, 2013b).Footnote 3

Participants and Data Collection Procedures

The corpus of publications meta-theoretically analysed in 2016 by applying the Grid for Meta-Theoretical Analysis in our paper consisted of 295 items extracted in 2015 from more than 10.000 texts filed in the specialized So.Re.Com“A.S. de Rosa” @-library (later improved at more than 15.000 texts, as March 2020).

Data Analysis Procedure

After finishing the meta-theoretical analysis of all the publications in our sample, we proceeded to analyse our results via descriptive statistics, textual analyses of abstracts and keywords (IRAMUTEQ 0.7 alpha 2) and, respectively, Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components of the categories identified with the Grid (R 3.3.2 package FactoMineR).

Two data analysis methods were employed in our study in order to explore our research questions: lexical analysis of abstracts, aimed to explore how the anthropological and ethnographic approaches were conceptualized and employed without any pre-imposed points of reference and/or categories, and, respectively, Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components, aimed to identify trends in how SRT was conceptualized within the anthropological and ethnographic approaches.

The abstracts of our data corpus were subjected to lexical analysis, based on the assumption that word co-occurrence consists an adequate basis for representing meaning: given that people learn words through hearing and/or reading them in specific combinations, they will employ this strategy in their own constructions of meaning. So far, this method has been widely used to explore how meaning is created and transmitted - in social psychology (e.g. Reinert 1983; Chaves et al. 2017), sociology (e.g. Robin 2003), marketing (e.g. Mathieu and Roehrich 2005) and cognitive psychology (e.g. Blot et al. 1994). By employing Hierarchical Descending Classification (HDC), we sought to identify repetitive language patterns in order to establish a hierarchy of lexical universes (i.e. scientific discourses) present in the corpus of data, in reference to illustrative variables of interest (Flick et al. 2015). HDC is a type of positioning text analysis which allowed us to make sense of words based on their natural context of occurrence - the discourse, conceived as a semantic space where words are considered based on their positioning and co-occurrences (Lund and Burgess 1996). We hoped that our results would shed light on our second research question (What characterizes the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT from a conceptual and methodological perspective?) by identifying how the anthropological and ethnographic approaches were conceived by the authors in the abridged version of their papers (i.e. the abstracts), where most of the papers address the main topics of interest from a theoretical as well as from a methodological point of view. We also sought to explore potential associations between thematic areas and methods and/or theoretical positioning, which have been identified through this method before (e.g. de Rosa and Gherman 2019).

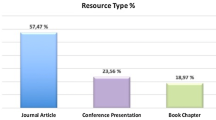

Our illustrative variables sought to reveal whether the lexical classes in our data are specific to certain timeframes and/or geo-cultural contexts, thus addressing our first research question (How did these approaches develop over time and across geo-cultural spaces?). Additionally, based on preliminary analyses ran on all of the publications on SRT in the SoReCom ‘A.S. de Rosa’ @-library (de Rosa 2014b, 2015, 2018; de Rosa et al. 2017, 2018a, b, c, 2019a, b) which revealed that the type of publication (resource type) and the scientific indexation of the paper may be associated with the use of certain research methods, thematic approaches and (re)conceptualizations of SRT: qualitative research may be less likely to be published in an article format and in indexed journals as compared to quantitative research, while more loose conceptualizations of the theory may be more likely to be employed in journal articles, especially the more prestigious ones, as measured by citation indices (de Rosa 2013b, 2015, 2016a; de Rosa and Arhiri 2019; de Rosa and Gherman 2019; de Rosa et al. 2017, 2018a, b, c; de Rosa, 2019a, b).

Our second data analysis strategy involved exploring the information we collected with the Grid through Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components (HCPC), a machine learning algorithm which combines three of the most widely used methods for multivariate data analyses (Husson et al. 2010a, b): Principal component methods (i.e. Multiple Correspondence Analysis - MCA, in our case), Hierarchical clustering and Partitioning clustering (i.e. the k-means method). This allowed us to identify how the papers in our corpus are grouped based on shared similarities and dissimilarities and thus, to identify trends in how the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT have been employed, from theoretical, conceptual, thematic and paradigmatic perspectives, as defined by the variables of interest from the Grid. HCPC was chosen because its findings are more accurate and robust, since the number of clusters is not defined a priori by the researcher, as it happens in k-means, but rather established through the Hierarchical Clustering technique, after the dimensionality of the data is reduced with MCA, so that the results may reflect general trends without the interference of outliers (Husson et al. 2010a, b). Each paper in our dataset was thus represented by a set of variables identifying how SRT was employed, the presence/absence of its main concepts and its theoretical and disciplinary underpinnings, as well as the thematic areas addressed along with methodological data, variables identified in the first stage of the meta-theoretical analysis – the data collection step, when the Grid was applied to all the papers. Hence, we expected our results to reflect patterns of conceptualization within the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT. Moreover, by including illustrative variables (which do not contribute to creating the dimensional space), we sought to further contextualize the identified trends from a bibliographic perspective (e.g. year of publication, geo-cultural context related to the author’s institutional affiliation, bibliometric indexes, resource type, etc.).

Results

Geo-Mapping the Diffusion of the Anthropological and Ethnographic Approaches to SRT

Due to size limitations, in this paper we restrict the use of the descriptive statistics to the goal of geo-mapping the dissemination of our approach to SRT across the world. Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of the bibliographic sources selected for this contribution according the criteria to be specifically related to the ‘anthropological’ and ‘ethnographic’ approaches to SRT by the “1st Author’s Institutional Affiliation Country”. The results clearly show the prominence of contributions in France and UK for the continent of Europe and, respectively, in Brazil, Mexico and Argentina for Latin America, along with a wide diffusion at the global scale.

The distribution of bibliographic sources related to the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to Social Representations Theory extracted in 2017 from the specialized repositories of the SoReCom “A.S. de Rosa” @-Library by the first author’s institutional affiliation country (performed in the Tableau software 10.3)

The Textual Analysis of the Abstracts and Keywords

The corpus was made up of 295 abstracts and their respective keywords, Initial Context Units (ICUs), which were initially analysed lexicometrically with the IRAMUTEQ (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires) software 0.7 alpha 2. The corpus was unfit for analysis (52.22% HAPAX >50%; 14.72% type/token ratio < 20%) and subsequently lemmatized by using the English dictionary incorporated in the software.

The results of the lemmatization showed a reduction in the number of HAPAX forms to 49.59%, and the type/token ratio to 11.72%, thus enabling us to carry out a Hierarchical Descending Classification (HDC) of ICUs on the whole lexical table (Reinert 1983).

By crossing the textual data from the abstracts (employed as active variables) with certain categories from the meta-data (employed as illustrative variables), we also tested whether certain clusters were specific to a certain geo-cultural context, timeframe, resource type, and, respectively, if they were more likely to be scientifically diffused according to citation indices.

The 295 ICUs were submitted to analysis according to the distribution of vocabulary; 1152 text segments, Elementary Context Units (ECUs), were produced of which 944 (81.94%) were retained in the clustering solution (Fig. 2).

Cluster 1 concentrates 462 ECUs, thus representing almost half of the whole corpus (48.94%). It comprises ECUs from most of the latest publications conducted within the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT (56.55% of the publications issued from 2010 and up to date are represented in this cluster), mainly in Latin America (77.98%) and consequently published in Portuguese and Spanish. These results are in accordance with the trend previously identified by de Rosa (2013b) and more recently on a wider corpus of 9660 publications (de Rosa et al. 2018a, b, c), who provided empirical evidence that Latin America, following Europe as the theory’s homeland, was the most fertilized scenario for SRT dissemination. The largest dissemination of SRT in the Latin American geo-cultural context is even more impressive when looking at the whole series of the dedicated events for disseminating the theory (the International Conferences on Social Representations I.C.S.R. organised every two years since 1992 in different continents), as it reveals a trend of an over increasing dominance of Brazilian authors and researchers among the participants and the presenters of individual contributions. An even clearer hegemony emerges when looking at the biannual series of the ten editions of Journadas Internacional sobre Representações Sociais (JIRS), scientific events hosted in Latin America (mainly in Brazil) up until 2017, where we found them featuring as organisers of collective activities (like Symposia, Round Table, Thematic Sessions), and requiring a networking effort in inviting other colleagues (de Rosa 2019b; de Rosa et al. 2015).

From empirical results based on meta-theoretical analyses, de Rosa also pointed out that SRT - at least in the first decades of the theory dissemination in the Latin American context – was employed more for its applied heuristic potentiality, than to develop theoretically, with the purpose of studying very diverse phenomena of high societal interest (de Rosa 2013b; de Rosa et al. 2018a, b, c). This explains the composition of this cluster, focused on ‘research methods’ specific to the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT and specific ‘thematic areas’ (objects of study representing the phenomena of high social interest, like education).

Cluster 2 concentrates 74 ECUs, thus representing a narrow, but distinct line of research within this approach (7.84%) developed between 2000 and 2009, mainly focused on health as thematic area and best illustrated by publications from Africa, Ghana, authored by Ama de Graft Aikins, who also worked in and collaborated with researchers from Europe, namely in the UK. This authors has dedicated most of her work to studying social representations of chronic illness in African communities, among which she intensively focused on diabetes and its impact on the sufferers as well as their families and extended communities (which included stigmatization, discrimination and prejudice), mental health, the impact of interventions and policies on the people, among which the ones focused on nutrition practices, and how they are linked to the populations’ previously held beliefs (e.g. Aikins 2003, 2006). One might argue that this contemporary line of research falls in line with the tradition laid out by Jodelet (1991) in her research on the social representations of madness in a French village, where the mentally ill were stigmatized based on the previously health beliefs of the population, who perceived mental illness as contagious. The results presented in Cluster 2 reveal that within the anthropological and ethnographic approaches, we may capture SRs and the group-specific knowledge they comprise within the socio-cultural context in which they occur, as the ethnographic methodology is meant to grasp to co-constructed reality of specific groups by observing them in social practices, actions and interactions (Duveen and Lloyd 1993; Almeida et al. 2000).

Finally, Cluster 3 comprises 408 ECU, and accounts for 43.22% of the entire corpus, similar in both size and structure with Cluster 1, but opposed to it in terms of content, as Cluster 1 focuses on empirical data, whereas Cluster 3 focuses on theoretical dimensions, mentioning disciplines and constructs (identity, social psychology, memory, history, communication among others). Thus, most of the publications represented in this cluster were authored by European researchers (64.14%), and issued as book chapters in French between 1990 and 1999, hence during the time in which the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT were theoretically defined through the contributions of Duveen and Lloyd (1986, 1990, 1993). The other dimension presented in this cluster is focused on one of the theoretical conceptualizations of SRT supported by empirical research conducted with ‘motivated ethnography’, as coined by Duveen and Lloyd 1993. They present a genetic perspective on SRs, linking them to social identity, thus bridging the gap between developmental and social psychology, as reflected in their articulations of the work of Piaget and Vygotsky (Psaltis et al. 2009).

A factorial correspondence analysis on the results of HDC reveals the most representative words for each class in a factorial space defined by two axes (Fig. 3). Here, we may see that the x-axis opposes Clusters 2 and 3 to Cluster 1, thus revealing an opposition between the publications within this approach from Latin America and, respectively, the ones from Europe and Africa. In line with de Rosa’s findings (de Rosa 2013b; de Rosa et al. 2018a, b, c), we may interpret this opposition based on the applied driven reference to the SRT in Latin America, where the objects of study range across a myriad of thematic areas, as observed in Cluster 1. In contrast to this, the research conducted in Europe is more theoretically driven and from the thematic point of view, like in Africa, is focused on objects of study that pertain to research areas, such as Identity and Health.

Across the y-axis, there is a polarization between Cluster 3 (closer to the positive pole) and Cluster 2 (closer to the negative pole), best explained by the two main areas of thematic interest in this approach, concentrated in the two clusters: Health and Identity. As expected, Cluster 2 expands in both spaces, as it concentrates the research methods employed all throughout this approach. Thus, closer to the positive pole, we have observation as a predominant method, while interviews appear to be closer to the negative pole. This reflects the methods preferred by each of the lines of research revealed by the other two clusters: while the research direction pioneered by Duveen and Lloyd employed both observation and interviews, the trend set out by Jodelet and continued by Aikins is mainly focused on interviews.

To conclude, the results of the textual analysis of the abstracts and keywords reveal that the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT are indeed homogenous in what regards the research methods employed, which mainly coincide with the ones proposed by Jodelet (1991) and Duveen and Lloyd (1993): participant observation, interviews, questionnaires, analysis of documents. Thus, our research questions may be answered insofar as the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT are methodologically defined by a distinct set of methods. Moreover, the thematic areas of our publications have contributed in the distinction between Clusters 2 and 3. Geo-culturally, the corpus of data distinguishes between Latin American contributions and, respectively, European and African ones, which supports the previous findings of Wachelke et al. 2015.

Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components

In order to further explore our research questions, namely the ones pertaining to the temporal and spatial diffusion of the approach in terms of conceptualization and thematic application, we chose to reduce the dimensionality of the data obtained through meta-theoretical analysis by employing clustering algorithms, specifically Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components (HCPC) with the R software 3.3.2, the FactoMineR package (Husson et al. 2010a, b). We ran the clustering algorithm on the results of a Multiple Correspondence Analysis, for which we employed bibliographic meta-data as illustrative variables and, respectively, data built analysing the references to concepts specific to SRT and to concepts pertaining to other theories from social sciences, typologies of SRs, other paradigmatic approaches to SRT and thematic areas as active variables. Ward’s Hierarchical Clustering algorithm was applied on the results of the MCA (72 dimensions were retained, explaining 90% of the inertia) and it revealed a three-cluster solution, which was subsequently consolidated through the k-means algorithm. Finally, the association between the variables inserted in the MCA and, respectively, the three clusters was tested through chi-square tests of association.

Clusters 2 and 3 are opposed to Cluster 1 in their specific, respectively generic use of SRT. Thus, our results reveal a significant opposition between Europe and Latin America from this point of view, in line with previous results (de Rosa 2013b, 2019b; de Rosa and d’Ambrosio 2008; de Rosa et al. 2015) and addressing our research question regarding the geo-cultural diffusion of the anthropological and ethnographic approaches. Moreover, both Cluster 2 and 3 mainly comprise ‘book chapters’, which reveals that the authors who refer to SRT in a specific manner within the anthropological and ethnographic approaches have a preference for this format rather than the article one. This may be explained by the research methods specific to anthropology and ethnography, mainly processed through qualitative data analysis techniques, which mainstream psychology typically deems as less efficient for the construction of science as compared to their quantitative counterparts (Valsiner 2006). Another reason could be that a book format may impose fewer restrictions regarding the presentation of content and especially the size of the paper, which may exceed journal standards in the case of ample, longitudinal ethnographies (e.g. Jodelet 1991). Finally, since SRT has not been included in the mainstream social psychology (Laszlo 1997), scientific journals dominated by mainstream social psychology editorial policies may be reluctant in publishing papers that employ it empirically or more so, that focus on theoretical developments.

While both Clusters 2 and 3 employ SRT specifically and thus represent a direction of research within our paradigmatic approach distinct from the one revealed by Cluster 1, they do present features that set them apart. Mainly, Cluster 3 uses SRT as an object for theoretical contributions on the anthropological and ethnographic approaches, comparing and contrasting SRT with other theories and other approaches. On the other hand, we find very little focus on other theories in Cluster 2 and no relationship drawn between the anthropological and ethnographic approaches and, respectively, other paradigmatic approaches. Although not significantly associated with modalities such as ‘empirical’ or ‘article in journal’, upon analysing the composition of the clusters, we do find that Cluster 2 is mostly made up of articles (50%), followed by book chapters (43.21%) and conference presentations (6.79%). Albeit not significantly associated with the modality “Journal article”, from this percentage analysis we may conclude that it is illustrative for this type of publication. Also, 55.56% of the papers in Cluster 2 are ‘empirical’. In conclusion, the difference between Clusters 2 and 3 is that Cluster 3 focuses on meta-theoretical developments, while Cluster 2 reflects both empirical and theoretical developments of the anthropological and ethnographic paradigmatic approaches to SRT.

Temporally, Clusters 1 and 3 oppose Cluster 2, in that the formers consist of papers published more recently (2002–2011), while the latter consists of paper published between 1982 and 1991. Thus, we may answer our research question regarding how the anthropological and ethnographic paradigmatic approaches have developed over time: close to its outset, publications were more focused on developing it theoretically and supporting their claims empirically (as revealed by Cluster 2), after which publications orientated themselves towards a more applied use in empirical research, basically assuming what was popular in the literature in the previous decade, and, respectively, towards positioning the approach in relation to other approaches and to other theories.

Cluster 1, which concentrates 39.32% of our publications (N = 116), is mostly made up of papers, which reference SRT generically (90% of all the generic papers may be found here). It contains mainly conference presentations (80% of all the conference presentations may be found here), and more than half of the first authors of these papers are affiliated to a Latin American institution (51.52% of all the publications from this geo-cultural space may be found in Cluster 1). The orientation of Cluster 1 is predominantly empirical (71.55% of its elements are empirical publications) and reflects a direction of research specific to the decade 2002–2011 (57.75% of its elements were published during that timeframe). Thus, the cluster is negatively associated with the presence of theoretical references to both SRT and other theories from Social Sciences and is not differentiated from the other two clusters thematically, as we found no positive or negative association with one of the 13 thematic areas. The direction of research represented by Cluster 1 supports our results from the textual analysis of abstracts and keywords, as well as previous results (de Rosa 2013b; de Rosa and d’Ambrosio 2008; de Rosa and Arhiri 2019; de Rosa and Gherman 2019; de Rosa et al. 2017, 2018a, b, c, 2019a, b). In fact it reveals the recent emergence of a large corpus of publications on SRT in Latin America where the theory is employed more for its applied heuristic potentiality, in order to empirically investigate diverse phenomena of high societal relevance, than for developing conceptually the theory itself (de Rosa et al. 2015).

Cluster 2 concentrates 55.25% of our publications (N = 163), thus constituting the most representative trend for the anthropological and ethnographic paradigmatic approaches to SRT. 91.11% of its papers were published between 1982 and 1991, mainly in book chapters (66.66%). Given that Cluster 2 reflects the crystallization of the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT, we find many theoretical references to concepts and constructs specific to SRT, as well as articulations with constructs from other theories. Thus, 99.38% of the elements of this cluster reference SRT specifically, in respect to SRs genetic aspects (socio-genesis, micro-genesis), SR’s functions (social identity related functions, orientation and control of social reality, guide for behaviour and intergroup relations, familiarization, facilitation of communication), processes (anchoring and objectification), transmission via communication and transformation (via knowledge, social identity, emotions, social changes, and practices), elements pertaining to SR’s structure, and, respectively, hegemonic and emancipated representations. In terms of constructs not specific for SRT, this cluster is strongly associated with behaviour, value, belief, categorization, norm, social processes, attitude, ideology, image, context, cognitive schemata and processes, judgement, cultural knowledge, practice, change communication, consensus, symbol, prejudice, action, metaphor, motivation, assimilation, prototype, attribution, development, language, common sense, stigma, emotion, stereotype projection, opinion and myth. Thematically, Cluster 2 comprises most of the publications on Intergroup relations and dimensions (88.24%) and Identity (62.05%), and all the publications which reference Attitude and Attribution Theories, which is not surprising, considering that these two theories, along with Social Identity Theory (which in this case “was reformulated” in the genetic perspective proposed by Duveen and Lloyd 1990, and thus integrated in SRT) are instrumental in describing thematic areas pertaining to identity and intergroup dimensions. These were the thematic areas in which Duveen and Lloyd have conducted their empirical research on children’s gender social identity, on which they founded their genetic perspective to SRT. Moreover, Jodelet’s study on madness (Jodelet 1991) amply referred to how social groups (the villagers and the mentally ill) related to each other according to villagers’ representation of madness.

Cluster 3, which concentrates 5.42% of our publications (N = 16), is largely theoretical, as 88.23% of its elements indicate, and mainly made up of book chapters (58.83%). Most of the papers from this cluster were authored by researchers in Europe (94.12%) and issued between 2002 and 2011 (70.59%). The bibliographical data regarding this cluster, along with its thematic areas (70.59% of its elements focus on SRT itself as a thematic area, while 11.76% of them also focus on the theory’s relationship with social psychology and other disciplines) point toward the nature of Cluster 3, which is how SRT is conceptualized within the anthropological and ethnographic paradigmatic approaches. Thus, we find significant associations with how Moscovici prescribed the appropriation of this theory: as being built upon the foundation set out by Durkheim’s theory of collective representations (Durkheim 1898), and studying how communication among members of groups builds, transmits and transforms social knowledge, in a process usually prompted by an event which brings about social change, an event with which the group members feel the need to be familiarized so that they know how to orient themselves in the newly created social environment, both verbally and behaviourally (Moscovici, 1961). Moreover, the theoretical references most strongly associated with Cluster 3 were Anthropological Theories, Sociological Theories, which coincide with Moscovici’s view on social psychology itself, about which he has firmly argued that it has undeniable connections with sociology and cultural anthropology (Moscovici and Marková 2006) and went on to define it as “the anthropology of contemporary society, just as anthropology itself is the social psychology of traditional society” (Moscovici 1985, p. 11). In addition to this, SRT is presented in contrast to mainstream theories in social psychology, such as the behaviourist, social influence (in the linear top-down assumption from consolidated majority towards powerless minorities) and socio-cognitive theories (represented conceptually as cognitive representations and attribution), as well as with theories from discursive psychology, a meta-theoretical articulation pointed out by Laszlo in 1997, when he argued that SRT distinguished itself from these two approaches despite their common areas. The meta-theoretical line given out by this cluster becomes more specific, and discusses critically the anthropological approach to SRT in conjunction with other paradigmatic approaches, namely the dialogical and narrative one (with reference to concepts such as semiotic triangle, cognitive polyphasia and themata) and, respectively, the structural approach (with reference to elements describing the structure of SRs). We find again a specific focus on the theoretical developments promoted by Duveen and Lloyd (1986, 1990, 1993) on the thematic areas of Identity and Culture, who, as previously mentioned, tried to bridge the contributions of Piaget (Genetic Psychology of Cognitive development) and Vygotsky (Socio-Cultural Theories) to approach developmental psychology from a perspective taking into account social representations; these results are in line with our textual analysis findings, namely with the sub-corpus represented by the third cluster. Children appropriate social identity culturally and symbolically, through the transmission of SRs via the practices and knowledge of adults in onto-genesis; socio-genesis describes how SRs are transformed socially and historically, while micro-genesis refers to how SRs change in social interactions between individuals (Duveen and de Rosa 1992).

Finally, upon closely examining our results, we may answer two research questions. Thus, there are two main thematic directions of research adopting the anthropological and ethnographic approaches: one focused on health (initiated by Jodelet 1989/1991 and continued up to date by authors such as Aikins 2003; Jodelet 2008; see also the review on this thematic area in de Rosa and Dryjanska 2017) and the other focused on identity and intergroup relations, especially in developmental and educational contexts, set out by Duveen and Lloyd (1986). Conceptually, these thematic areas, through their study of specific objects, have traditionally focused on certain dimensions of SRT:

-

1.

The first one examines the dynamics of social representations in groups faced with social change (e.g. in Jodelet’s 1991 research, the insertion of the mentally ill in the community; in Aikins’ studies, newly implemented social policies concerning health aspects) by investigating how SRs are developed and transformed by people through their practices and previously held beliefs. We might say that this direction of research conceptually corresponds to the dynamic nature of SRs, emphasized by Moscovici and ultimately studied by him in his 1961 opus prima, where psychoanalysis was the new social object that brings about a social change as well as the emergence of new SRs in France (for a meta-theoretical analysis of the first and second edition of the Moscovici opus prima, respectively published in 1961 and 1976 see de Rosa 2011).

-

2.

The second line of research is applicable, as Duveen and Lloyd pointed out, to a restricted number of social objects, in a certain sense opposed to the first line described above in terms of novelty (the objects under investigation are usually not new). Instead, a substantial focused is placed upon the interplay between the development of social identity and social representations and, respectively, their reciprocal influence and how this impacts children (e.g. Carugati 1990; Castorina 1999, 2010; Corsaro 1990; D'Alessio 1990; Dagenais 2000; De Abreu and Cline 1998). This very ample line of research may be regarded as an original contribution to SRT because it adds a social developmental dimension to the theory, best surmised by the term ontogenesis, but deeply integrated with micro-genetic and socio-genetic construction of knowledge, emphasizing the role of communication in social representations processes in the context of a genetic social psychology (Moscovici 2010; Moscovici et al. 2013; Psaltis 2015) for understanding the culture and its heterogeneity in the dynamic co-existence (rather than replacing) of common sense and science (de Rosa 2010)

Therefore, these two lines of research would qualify as theoretical orientations of the anthropological and ethnographic approaches, interdependent with their methodologies, and yet identifiable amongst the other paradigms.

Discussion

This paper aimed to address - through its research questions and subsequent methodological endeavour - the current state of the anthropological and ethnographic approaches to SRT in what concerns their relationship with the original formulations of the theory as a revolutionary paradigm (Sammut et al. 2015b), its iconoclastic impetus (Bauer 2015) and subsequent epistemological developments as supra-disciplinary research fields (de Rosa 2013a, b; Camargo et al. 2018).

More recently the SRT has been integrated with Semiotic-Cultural Psychology Theory (SCPT) (Salvatore 2016; Valsiner 2007; Valsiner and Rosa 2007) and common ground with socio-cultural studies, community and clinical psychology, anthropology, sociology, semeiotic, communication studies has been recognised due to the societal implications of the sense-making in shaping important social issues both for institutions and citizens, addressing the role of culture conveyed in social and media representations and embedded in social practices for policy-making (Mannarini et al. 2020).

In this contribution basically, we aimed to empirically explore the theoretical and methodological identity of the anthropological and ethnographic approaches and their articulations with SRT. According to several theoreticians, such as de Rosa (2013b), Jolicoeur (2015), Garnier (2015), these approaches to SRT deserve to be recognised in terms of both distinctiveness from other approaches and major contributions to SRT. Our findings support the two aspects emphasized above: on the one hand, the research within the anthropological and ethnographic approaches continues the theoretical supra-disciplinary tradition set out by Moscovici in his focus on the socio-dynamic nature of SRs, and on the other hand, has a strong affiliation to anthropology and ethnography, with which it shares methodological similarities.

Moscovici (1961) and the pioneer exponents of the anthropological and ethnographic approaches (e.g. Jodelet 1991; Duveen and Lloyd 1993) conceptualized SRs dynamically by recommending that they be studied as they are co-constructed socially through referencing processes such as the SRs genesis, transmission and transformation, typically appraised through qualitative methods, such as motivated ethnographies and observation techniques. Thus, our findings support the dynamic conceptualization of SRs within these specific approaches.

In order to reply to the potential question of a reader “In what sense do the commonly used methods bridge diverse disciplines?” it is important to stress once again that Social Representations Theory emerged as an alternative to a narrow mainstream Social Psychology (Moscovici and Marková 2006) with the explicit purpose of integrating several disciplinary approaches on the co-construction of social thought and social actions through communication, among which sociology, anthropology, social constructionism, cultural studies, communication studies, semeiotics, linguistic, discursive social psychology, political science, philosophy, critical psychology, ethnographic perspectives (Collier et al. 1991; Jodelet 2008; de Rosa 2013a, b; Sammut et al. 2015a), with the purpose of “enlarging social psychology so that it comprehends the full range of interdependent influences that integrate society, culture, and the individual.” (Jodelet 2008, p. 417).

The integrative perspective proposed by Moscovici (1961) and refined by others (e.g. Abric 1984; Doise 1986; Duveen and Lloyd 1993; Jodelet 1991; de Rosa 2013a, b; Sammut et al. 2015b; Mannarini et al. 2020) is evident at both the theoretical level, as well as the methodological one. Denise Jodelet illustrates Moscovici’s integrative perspective in her account of how the concept of social representations was articulated: “To cope with the phenomena of social representations implied to combine concepts borrowed from neighbouring disciplines (from attitude and belief to ideology and culture) relocating them in a holistic framework that refused the reduction of social representation to any one of them. Such a procedure anticipated complexity theories and implemented interdisciplinary requirements.” (Jodelet 2008, p. 417).

Indeed one of the critical scopes for launching in 1994 the research program for a meta-theoretical analysis of the whole corpus of the literature on Social Representation - at a time that of the increasing popularity of the SRT after almost two decades of latency in the dissemination outside the academic circles in France (de Rosa 2013a, b) - was to empirically investigate to what extent the methods used to explore social representations as processes as well as products were chosen just as tools to investigate the social objects in question, irrespective of their traditional use within a certain theoretical orientation and more important irrespective of the paradigmatic assumptions specific of the social representation theory. This interest was guided by the hypothesis that - at that time - there was a large tendency to refer to the theory in a very general or generic way, withouth adequating the methodological design to the complexity of the paradimatic assumptions that distingueshed the theory of social representations from other theories that were used to study the same social object: see for example the wide correspondence of the same objects investigated in the ‘90 by authors who referred to “social cognition” and those who referred to “social representation” too often used as equivalent disregarding the epistemological distinctions between the two (for a critical review see de Rosa 1990, 1992; Duveen and de Rosa 1992). The same happened almost one decade later for the authors who referred to the radical “discourse analysis” (too often misunderstood as simple content analysis of the discourse) and “social representations” as they were interchangeable (for a critical review see de Rosa 2003, 2006). The need for developing integrative multi-method research designs coherent with the multi-construct and multi-theoretical inspiration of the social representation theory - that more than a narrow theory is a supradisciplinary paradigm - led to the development of a “modelling approach” beyond the simplistic sum of different research techniques as in the traditional multi-method approach (de Rosa 2013a, b, 2014a). The integrative vision proposed by the “modelling approach” not only concerns the different techniques to be designed coherently with the dimensions and constructs under investigation (attitudes, beliefs, emotions, social and collective memory, actions, values, meanings, discourse, interaction.....), but it also promotes an integration of different research traditions developped within the unified view of the social respresentations theory, like the “socio-dynamic approach”, the “structural approach”, the “dialogical approach”, the “anthropological and ethnographic approaches”, too often reflecting the opposition rather than the potential and fruitful integration of different way to investigate the same research object or field through a more critical integrative view, that of course requires higher level of theoretical and methodological expertise.

Though qualitative methods are still less employed in mainstream social psychology - based on experimental lab based design or individualistic approaches and less concerned for the socio-cultural, contextual and interactionist dimensions, as compared to sociology and anthropology - our empirical results demonstrates that the literature inspired by social representations has traditionally and largely adotped several qualitative methods, such as (participant) observation, ethnographies, document analysis, episodic interviews, semi-directive interviews, free interviews - coherently with the epistemological option for the anthropological and ethnographic approaches - sometimes even along with experiments and surveys (Rateau and Lo Monaco 2013).

Our research is not without limitations. Many of the conference presentations were available in abstract form only, which may have influenced some of our results.

As another limit, we may state that in this specific contribution we did not compare the chosen approaches to the others (one of goals of de Rosa’s wider research program); this was due to the fact that our endeavour was set out driven by a “within” perspective to find homogenous traditions of research and conceptualization within the anthropological and ethnographic approaches, as a part of the wider research program where other contributions are focused on other approaches and other research lines, in view of providing an overall picture of different approaches developed/used by authors over time, across multiple cultural scenarios and diversified thematic and applied fields in various geo-cultural contexts of the dissemination of the theory.

Future publications will present comparative analyses among the five approaches based on the overall results of de Rosa’s research program and will also be enriched by qualitative accounts drawn from the auto-biographical narratives about their encounter with the SRT by the leading scientists across several generations for a living biography of a theory. In fact this ambitious research program is based not only on the systematic meta-theoretical analysis of the reified texts of different resource types (books, articles in journals, conference presentations, reports, theses, web-documents, etc.), but also on the scientific accounts of their protagonists (from the founder of the theory to a multi-generational population of leading social scientists) and on the events for the theory dissemination, in particular the dedicated series of international conferences (I.C.S.R. and J.I.R.S.) as occasion of networking (de Rosa, 2016a, b, 2019a, b), thus profiling authors and co-authors (de Rosa et al. 2017, 2018a, b, c), also through social network analysis to reply to the question “who is working with whom, from which institutional affiliation countries/continents, on what, by which theoretical and methodological approach, by which impact” (de Rosa et al. 2020).

Notes

Some of the approaches are often confined in specific circles of the so called ‘school of Aix’ at the time directed by Abric as regards the structural approach or the ‘school of Geneva’ at the time led by Doise for the socio-dynamic approach, etc. However it is interesting to look at the epidemiology of ideas, empirically reconstructing - through the meta-theoretical analysis - the dissemination of these approaches over the decades and across different research centres in various continents/countries worldwide, also analysing the role of networking within the scientific community inspired by Social Representation Theory, by looking “who is working with whom, when, and on what, by using which approach”

These include, among others, the bi-Annual International Conferences on Social Representations (I.C.S.R.) and Jornada Internacional sobre Representaçoes Sociais (J.I.R.S.) and the serial dedicated training events (http://www.europhd.eu/international-summer-schoolsand http://www.europhd.eu/international-lab-meetings) organised since 1995 by the European/International Joint Ph.D in Social Representations and Communication.

Prior to the statistical analysis based on lexical analysis of the abstracts, using the Grid for meta-theoretical analysis the ad hoc trained analysers have detected very carefully not only which are for example the specific theoretical constructs of the Social Representations theory and other theories and disciplinary approaches in social sciences elicited by the authors in their texts, but also at which purpose with reference to the Social Representation theory (integration, differentiation, comparison….). Therefore the results based on the lexical analysis of the abstracts are also contextualised in a large framework of results, that - due to the limit of space - could not be presented in this article, but that are objects of other publications included in the list of references for readers interested to expand their knowledge on this multi-year research program.

References

Abric, J.-C. (1984). A theoretical and experimental approach to the study of social representations in a situation of interaction. In R. M. Farr & S. Moscovici (Eds.), Social representations (pp. 169–183). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Aikins, A. d.-G. (2003). Living with Diabetes in Rural and Urban Ghana: A Critical Social Psychological Examination of Illness Action and Scope for Intervention. Journal of Health Psychology, 8(5), 557–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591053030085007.

Aikins, A. d.-G. (2006). Reframing applied disease stigma research: A multilevel analysis of diabetes stigma in Ghana. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 16(6), 426–441 https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.892.

Almeida, A. M. d. O., Santos, M. d. F. d. S., & Trindade, Z. A. (2000). Representacoes e praticas sociais: contribuicoes teoricos e dificuldades metodologicas. Temas em Psicologia, 8(3), 257–267.

Bauer, M. W., & Gaskell, G. (1999). Towards a paradigm for research on social representations. Journal for the theory of social behaviour, 29(2), 163–186 https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5914.00096.

Bauer, M. (2015) On (social) representations and the iconoclastic impetus, In G. Sammut, E. Andreouli, E., G. Gaskell, & J. Valsiner (Eds.) The Cambridge handbook of social representations (pp. 43–63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Billig, M. (1991). Ideology and beliefs. London: Sage.

Blot, I., Hammer, B., & Le Roux, D. (1994). Traitement des questions d'opinions «ouvertes»: utilisation d'ALCESTE, outil d'assistance à l'analyse. ICO. Intelligence artificielle et sciences cognitives au Québec, 6(1–2), 101–105.

Camargo, B. V., Scholsser, A., & Giacomozzi, A. I. (2018). Aspectos Epistemológicos do Paradigma das Representações Sociais. In E. Diogenes de Medeiros, L. Fernandes de Araújo, M. da Penha Coutinho de Lima Coutinho, and L. Silva de Araújo (Eds.), Representações Sociais e Prática Psicossociais, (pp. 153–167). Curitiba: Editora CRV.

Carugati, F. (1990). From social cognition to social representation in the study of intelligence. In G. Duveen & B. Lloyd (Eds.), Social representations and the development of knowledge (pp. 126–143). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Castorina, J. A. (1999). The social knowledge of children: psychogenesis and social representations. Prospects, 29(1), 135-150. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02736830

Castorina, J. A. (2010). The Ontogenesis of Social Representations: A Dialectic Perspective. Papers on Social Representations, 19(18), 18.1–18.19 Retrieved from http://psr.iscte-iul.pt/index.php/PSR/article/download/397/353/.

Chaves, M. M. N., dos Santos, A. P. R., dos Santosa, N. P., & Larocca, L. M. (2017). Use of the software IRAMUTEQ in qualitative research: an experience report. In A. P. Costa, L. P. Reis, F. N. de Sousa, A. Moreira, & D. Lamas (Eds.), Computer Supported Qualitative Research (pp. 39–48). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Collier, G., Minton, H. L., & Reynolds, G. (1991). Currents of thought in American social psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Corsaro, W. A. (1990). The under life of the nursery school: young children's social representations of adults rules. In G. Duveen & B. Lloyd (Eds.), Social representations and the development of knowledge (pp. 11–25). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dagenais, D. (2000). La représentation des rôles dans une étude de collaboration interinstitutionnelle. Revue des sciences de l'éducation, 26(2), 415–438. https://doi.org/10.7202/000129ar.

D'Alessio, M. (1990). Social representations of childhood: an implicit theory of development. In G. Duveen & B. Lloyd (Eds.), Social representations and the development of knowledge (pp. 70–90). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Abreu, G., & Cline, T. (1998). Studying social representations of Mathematics learning in multi-ethnic primary schools: work in progress. Papers on Social Representations, 7(1–2), 1–20 Retrieved from http://psr.iscte-iul.pt/index.php/PSR/article/view/258.

de Rosa, A. S. (1990). Considérations pour une comparaison critique entre les R.S. et la Social Cognition. Sur la signification d'une approche psychogénetique à l'étude des représentations sociales. Cahiers Internationaux de Psychologie Sociale, 5, 69–109.

de Rosa, A. S. (1992). Thematic perspectives and epistemic principles in developmental Social Cognition and Social Representation. The meaning of a developmental approach to the investigation of. S.R. In M. von Cranach, W. Doise, & G. Mugny (Eds.), Social representations and the social bases of knowledge (pp. 120–143). Lewiston: Hogrofe & Huber Publishers.

de Rosa, A. S. (1994). From theory to meta-theory in social representations: The lines of argument of a theoretical-methodological debate. Social Science Information, 33(2), 273–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901894033002008.

de Rosa, A. S. (2002). Le besoin d’une “théorie de la méthode”. In C. Garnier (Ed.), Les formes de la pensée sociale (pp. 151–187). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

de Rosa, A. S. (2003). Communication versus discourse. The “boomerang” effect of the radicalism in discourse analysis. In J. Laszlo & W. Wagner (Eds.), Theories and Controversies in Societal Psychology (pp. 56–101). Budapest: New Mandate.

de Rosa, A. S. (2006). The boomerang effect of radicalism in Discursive Psychology: A critical overview of the controversy with the Social Representations Theory. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 36(2), 161–201 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.2006.00302.x.

de Rosa, A. S. (2008). (Ed.), Looking at the History of Social Psychology and Social Representations: Snapshot Views from Two Sides of the Atlantic (pp. 161–202). Rome: Carocci.

de Rosa, A.S., (2010). Mythe, science et représentations sociales, In D. Jodelet and E.Coelho Paredes, (Eds), Pensée mytique et représentations sociales, (pp. 85–124) L’Harmattan, Paris.

de Rosa, A.S. (2011). 1961–1976: a meta-theoretical analysis of the two editions of the “Psychanalyse, son image et son public”. In C. Howarth, N. Kalampalikis and P. Castro (Eds.), A half century of social representations: discussion on some recommended papers, Special Issue, Papers on Social Representations, 20(2), 36.1.-36.34. Retrieved from http://psr.iscte-iul.pt/index.php/PSR/article/view/451

de Rosa, A. S. (2013a). Taking stock: a theory with more than half a century of history. Introduction to: A.S. de Rosa (Ed.), Social Representations in the social arena. (pp. 1–63.) New York/London: Routledge.

de Rosa, A. S. (2013b). Research fields in social representations: snapshot views from a meta-theoretical analysis. In A. S. de Rosa (Ed.), Social Representations in the Social Arena (pp. 89–124). New York/London: Routledge.

de Rosa, A.S. (2014a). The role of the Iconic-Imaginary dimensions in the Modelling Approach to Social Representations. In A. Arruda, M.A. Banchs, M. De Alba and R. Permanadeli (Eds.), Special Issue on Social Imaginaries, Papers on Social Representations. 23, 17.1–17.27. Retrieved from http://www.psych.lse.ac.uk/psr/

de Rosa, A.S. (2014b). The So.Re.Com . “A.S. de Rosa” @-Library: A Multi-Purpose Web-Platform in the supra-disciplinary field of Social Representations and Communication. In Inted 2014 Proceedings (pp. 7413–7423). Valencia: INTED Publications. Retrieved from http://library.iated.org/?search_text=publication%3AINTED2014&adv_title=&rpp=25&adv_authors=&adv_keywords=&orderby=page&refined_text=de+Rosa

de Rosa, A.S. (2015). The Use of Big-Data and Meta-Data from the So.Re.Com A.S. de Rosa @-Library for Geo-Mapping the Social Representation Theory’s Diffusion over the World and its Bibliometric Impact, 9thInternational Technology, Education and Development Conference. In INTED 2015 Proceedings (pp. 5410–5425). Madrid: INTED Publications. Retrieved from http://library.iated.org/view/DEROSA2015USE

de Rosa, A.S. (2016a). Mise en réseau scientifique et cartographie de la dissémination de la théorie des représentations sociales et son impact à l'ère de la culture bibliométrique. In G. Lo Monaco, S. Delouvée and P. Rateaux (Eds.), Les représentations sociales (pp. 51–68). Belgique: Editions de Boeck.

de Rosa, A.S. (2016b). The European/International Joint PhD in Social Representations and Communication: a triple “I” networked joint doctorate. In D. Halliday and G. Clarke (Eds.), Book of Proceedings of the 2ndInternational Conference on Development in Doctoral Education and Training (pp. 47–60). London: Epigeum Oxford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.ukcge.ac.uk/ICDDET.

de Rosa, A.S. (2018). The So.Re.Com. “A.S. de Rosa” @-library: Mission, Tools and Ongoing Developments. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology 4th Edition (pp. 5237–5251). Hershey: IGI Global.

de Rosa, A. S. (2019a). For a Biography of a Theory. In N. Kalampalikis, D. Jodelet, M. Wieviorka, D. Moscovici, & P. Moscovici (Eds.), Serge Moscovici. Un regards sur les mondes communs (pp. 155–165). Paris: Editions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme (collection "54").

de Rosa, A.S. (2019b). The story continues: for a “biography of the theory” through the International Conferences on Social Representations, In Seidman, S. Pievi, N. Eds. Identidades Y Conflictos Sociales. Aportes y desafíos de la investigación sobre representaiociones sociales, (pp.138–202), Ed. de Belgrano. Buenos Aires.

de Rosa, A.S. (1992–2020). State of the art of the meta-theoretical analysis of the social representations literature. Papers presented at the yearly series of the International Lab Meeting– Winter session, European/International Joint PhD in S.R.&C. Research Centre and Multimedia Lab, Rome. Retrieved from http://www.europhd.net/39th-international-lab-meeting-winter-session-2020-scientific-program and http://www.europhd.net/39th-international-lab-meeting-winter-session-2020-scientific-materials

de Rosa, A. S., & Arhiri, L. (2019). The anthropological and ethnographic approaches to social representations theory: a systematic meta-theoretical analysis of publications based on empirical studies. Quality & Quantity, 53(6), 2933–2955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-019-00908-3.

de Rosa, A. S. D’Ambrosio, M.L. (2008). International Conferences as Interactive Scientific Media Channels. The History of the Social Representations Theory through the Eight Editions of the ICSR from Ravello (1992) to Rome (2006). In de Rosa, A. S. (Ed.), Looking at the History of Social Psychology and Social Representations: Snapshot Views from Two Sides of the Atlantic ”, Rassegna di Psicologia, 2, 153–207.

de Rosa, A.S., & Dryjanska, L. (2017). Social Representations, Health and Community. Visualizing selected results from the meta-theoretical analysis through the “Geo- mapping” technique. In A. Oliveira and B. Camargo Vizieu (Eds.) Representações sociais do envelhecimento e da saúde, (pp. 338–366). João Pessoa: Editora Universitária da UFPB.

de Rosa, A.S. & Gherman, M.A. (2019). State of the art of social representations theory in Asia: An empirical meta-theoretical analysis. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, vol. 13,e9, https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2019.1.

de Rosa, A.S., Bocci, E., & Dryjanska, L. (2018a). The Generativity and Attractiveness of Social Representations Theory from Multiple Paradigmatic Approaches in Various Thematic Domains: An Empirical Meta-theoretical Analysis on Big-data Sources from the Specialised Repository “SoReCom ‘A.S. de Rosa’ @-library”, Papers On Social Representations, 27(1), 6.1. – 6.35. Retrieved from: http://psr.iscte-iul.pt/index.php/PSR/article/view/466

de Rosa, A.S., Dryjanska, L., Bocci, E., (2017). Profiling authors based on their participation in Academic Social Networks INTED2017, (Valencia, SPAIN, 6-8th of March, 2017). In Inted 2017 Proceedings, (pp. 1061–1072), Madrid: INTED Publications. http://library.iated.org/publications/INTED2017

de Rosa, A. S., Dryjanska, L., & Bocci, E. (2018b). The impact of the impact: Meta-Data Mining from the SoReCom “A.S. de Rosa” @ Library. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology 4th Edition (pp. 4404–4421). Hershey: IGI Global.

de Rosa, A. S., Dryjanska, L., & Bocci, E. (2018c). Mapping the dissemination of the Theory of Social Representations via Academic Social Networks. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology 4th Edition (pp. 7044–7056). Hershey: IGI Global.

de Rosa, A.S., Forte, T., & Dryjanska, L. (2015) Geo- mapping the evolution of the social representations theory: the Latin America scenario. In M. E. Batista Moura, A. M. Silva Arruda, L. F. Rangel Tura (Eds) Anais da IX Jornada Internacional sobre Representações Sociais JIRS e VII Conferência Brasileira sobre Representações Sociais CBRS, pp. 412. Centro Universitario UNINOVAFAPI.

de Rosa, A.S., Ramazanova, A., & Dryjanska, L. (2016) Cultural dynamic of Education, Science and Social Representations in the worlwide research landscape and contemporary media scenario. EADTU2017 Proceedings – The Online, Open and Flexible Higher Education Conference: Enhancing European Higher Education ‘Opportunities and impact of new modes of teaching'(Rome, 19–21 October 2016), pp.18–33.

de Rosa, A.S. Zinilli, A. Latini, M. (2020) Science production and dissemination “by” and “within” the Social Representations scientific community in the bibliometric era: “Who” has collaborated “with whom”, “on what”, “when” and “from which institutional affiliation’s Country/Continent”, 15th International Conference on Social Representations, 2–5 September 2020, Athens.

Doise, W. (1986). Les représentations sociales : définition d’un concept. In W. Doise & A. Palmonari (Eds.), Textes de base en psychologie : L’Etude des représentations sociales (pp. 81–94). Paris : Delachaux et Niestlé.

Durkheim, E. (1898). Representations indivuduelles et representations collectives. Revue de metaphysique et de morele, 6, 273–302.

Duveen, G., & de Rosa, A. (1992). Social representations and the genesis of social knowledge. Papers on Social Representations, 1(2–3), 94–108.

Duveen, G., & Lloyd, B. (1986). The significance of social identities. British Journal of Social Psychology, 25(3), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1986.tb00728.x.

Duveen, G., & Lloyd, B. (Eds.). (1990). Social representations and the development of knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Duveen, G., & Lloyd, B. (1993). An ethnographic approach to social representations. In G. M. Breakwell & D. V. Canter (Eds.), Empirical approaches to social representations (pp. 90–109). New York: Clarendon Press.

Emiliani, F., & Passini, S. (2017). Everyday life in Social Psychology. Journal for the Theory and Social Behaviour, 47(1), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12109.

Flick, U., Foster, J., & Caillaud, S. (2015). Researching social representations. In G. Sammut, E. Andreouli, G. Gaskell, & J. Valsiner (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of social representations (pp. 64–80). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Garnier, C. (2015). Construction d’une théorie: les représentations sociales\ A contrução de uma teoria: as representações sociais. Revista Educação e Cultura Contemporânea, 12(27), 4–53 Retrieved from: http://periodicos.estacio.br/index.php/reeduc/article/view/1246/612.

Glass, G. (1976). Primary, Secondary, and Meta-Analysis of Research. Educational Researcher, 5(10), 3–8 Retrieved from: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7cd7/3bb41e2d79dff4a9524c4fd7bbc01bc1991e.pdf.

Guareschi, P.A. (2000). Representações sociais: avanços teóricos e epistemológicos. Temas em Psicologia, 8(3), 249–256. Retrieved from: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-389X2000000300004&lng=en&tlng=.