Abstract

The detrimental effects of sexism on women’s professional lives are well known. However, what is still under-investigated is whether women would all be affected to the same extent by exposure to sexist manifestations in the workplace, or individual variables, such as ideological standpoints, moderate women’s reactions to such events. We conducted two experimental vignette studies aimed to analyze the relations between sexism and women’s psychological distress. In Study 1, performed with 179 Italian adult women (Mage = 24.17, SD = 9.45), exposure to a hostile sexist message and to a benevolent sexist message fostered participants’ anxiety and depression. The effects of hostile sexist message were significantly stronger than the effects of benevolent sexist message. In Study 2, performed with 514 Italian adult women (Mage = 24.80, SD = 7.30), we confirmed the links above. Moreover, we showed that the individual level of sexism (that had negative associations with the dependent variables) partially buffered them: The effects on anxiety and depression of exposure to a hostile sexist message were stronger among participants with low versus individual levels of hostile sexism. Analogously, the effects of exposure to a benevolent sexist message were stronger among participants with low versus individual levels of benevolent sexism. Strengths, limitations, and possible developments of this research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last five decades, significant milestones have been undoubtedly registered in the field of gender equality (Equal measures 30 2019). However, the World Economic Forum (2020) forecasts that full gender equality will not be reached before another century. The gender gap is particularly severe in the labor market. Globally, only the 55% of adult women are employed, compared to the 78% of their male counterpart, with a gender pay gap equal to 40% (Equal Measures 30 2019; World Economic Forum 2020). Numerous barriers still impede gender equality in work domains, among which occupational segregation, the sticky floor (e.g., Booth et al. 2003; Eurostat 2019), and glass ceiling effects (Eurostat 2019), not to mention the large amount of female unpaid work and housework and the spread of sexist discriminations (Equal Measures 30 2019; World Economic Forum 2020). These phenomena, unequivocal expressions of sexism, compromise women’s equal participation in work domains (Equal Measures 30 2019), impair their performance, and undermine their psycho-physical well-being (e.g., McLaughlin et al. 2017; Pacilli et al. 2019).

The detrimental effects of sexism on women’s professional lives are well known. However, what is still under-investigated is whether women would all be affected to the same extent by exposure to sexist manifestations in the workplace, or individual variables, such as ideological standpoints, moderate women’s reactions to such events. The present research builds on this paucity by investigating whether the psychological distress associated with the exposure to workplace sexism would vary according to women’s endorsement of ambivalent sexism.

Ambivalent Sexism and Its Palliative Function

Sexism is a two-face prejudice towards women (Glick and Fiske 1996, 2001) that reflects ambivalence towards women by two different and complementary sides, respectively hostile and benevolent sexism. Hostile sexism (HS) is an overtly adversarial attitude towards women, according to which women who do not conform themselves to stereotypical gender roles are manipulators that take advantage of men using their sexuality. Benevolent sexism (BS), subtler than hostile sexism, expresses a patronizing attitude according to which women who conform to stereotypical gender roles are perceived as wonderful, sensitive, and fragile creatures who deserve love and protection from men (Glick and Fiske 1996, 2001).

Ambivalent sexism overcomes the sociocultural field (Glick et al. 2000) and affects women in a wide range of domains: from the workplace environment (e.g., Pacilli et al. 2019) to legitimating gender violence (Glick et al. 2002), from blaming attribution to violence victims (e.g., Abrams et al. 2003, for a review see Penone and Spaccatini 2019) to fostering sexual objectification of women (e.g., Cikara et al. 2011).

Thus, sexism works to women's disadvantage; however, it can be interiorized, expressed, and tolerated even by women themselves (e.g., Barreto and Ellemers 2005a, b; Glick et al. 2000; Kilianski and Rudman 1998). Women’s endorsement of sexism plays the social function of maintaining the status quo and, thus, the perpetuation of men’s advantages (Glick and Fiske 1996). This is consistent with the System Justification Theory (Jost and Banaji 1994), according to which people tend to endorse a psychological motivation to justify and perceive the social arrangement as fair, legitimate, inevitable, and good, even when it works at one’s disadvantages (Jost et al. 2004). Colluding with an unfair system could have relevant costs, especially for disadvantaged groups and individuals. When experiencing unfair events, the endorsement of system-justification beliefs could function as a stressor for individuals (Wakslak et al. 2007), with a negative impact on their well-being (e.g., Eliezer et al. 2011). However, the endorsement of system-justification beliefs could have a palliative function as well (for a review, see Jost and Hunyady 2003), buffering the discrimination-related stress (e.g., Levine et al. 2017). As a consequence, disadvantaged individuals who hold a system justifying ideology might paradoxically feel better and perceive the situation as fair, controllable, and inevitable by denying discrimination or rationalizing and interiorizing inequality (Jost and Hunyady 2003).

Compared to other constructs such as system justification (e.g., Levine et al. 2017), sexism has attracted less academic attention in the examination of the palliative function of ideology. However, preliminary research evidence has indicated that sexism too may function as a system justifying ideology (Vargas-Salfate 2017). Cross-cultural studies revealed that where societal gender inequality is high (vs. low), women endorse ambivalent sexism to a greater extent (Glick et al. 2000; Napier et al. 2010). Other indirect evidence indicates that women endorsing a BS perspective are less willing to engage in collective action (Becker and Wright 2011). Furthermore, women exposed to complementary gender stereotypes perceive gender inequality as fair and legitimate (Jost and Kay 2005). Such a gender-specific system justification leads benevolent sexist women to express greater life satisfaction (Connelly and Heesacker 2012; Hammond and Sibley 2011; Napier et al. 2010), especially when they endorse HS too (Hammond and Sibley 2011). Most of the available research investigated the palliative function of BS. However, it has been found that HS could absolve a buffering function too, being associated with greater life satisfaction since childhood (Vargas-Salfate 2017). In this light, the endorsement of hostile and benevolent sexism could be conceived as a form of self-protection, given that provides a buffer against negative outcomes of gender inequality, pushing, at the same time, women to rationalize, accept, and sustain a sexist social arrangement (Hammond and Sibley 2011).

Consequences of Sexism in the Workplace

A considerable amount of literature documented the detrimental impact of workplace sexism on women’s professional life. Sexist events produce financial stress, unwanted and premature job change, and a general impairment of women’s occupational satisfaction (e.g., McLaughlin et al. 2017; Sojo et al. 2016). Beyond reducing women’s self-perceived competence and suitability for work, sexism also obstacles their attainment of power and career progression (e.g., Barreto and Ellemers 2005a; Beaton et al. 1996; Elliot and Smith 2004; Swim et al. 1995; Tougas et al. 1999). Further, confronting with sexism during job selection results in women’s poorer performance because of intrusive thoughts about their own (in)competence and of the perception of the situation as sexist (BS in Dardenne et al. 2007; BS in Dumont et al. 2010; both BS and HS in Grilli et al. 2020).

Most interestingly for our purpose, exposure to sexism in workplace detrimentally affects women’s psychological well-being, with possible long-term health complications. Research based on the anonymous self-reported occurrence of sexist episodes in workplace documents that women’s frequent experience of sexism results in poorer physical (e.g., sleep troubles, gastrointestinal disturbances, headaches) and psychological (e.g., tension, anger, anxiety: see Borrell et al. 2010; Rubin et al. 2019; Manuel et al. 2017; for meta‐analyses, see Chan et al. 2008; Sojo et al. 2016) health.

Although to a lesser extent, experimental evidence of the effect of workplace sexism on psychological adjustment and well-being is available. In a lab experiment, Schneider and colleagues (2001) showed that women involved (vs. not involved) in a HS interaction with a male confederate appraised the situation as more demanding, reported stronger negative emotional reactions, and higher cardiovascular reactivity during the interactions. Adopting physiological measures, Solomon and colleagues (2015) demonstrated that while exposure to men’s HS comments immediately increased women’s level of stress more than exposure to BS comments, exposure to BS (vs. HS) comments determined a more prolonged impairment of cardiovascular recovery.

This literature provides compelling evidence that workplace sexism significantly contributes to women’s health impairment. However, there remains a paucity of evidence on possible moderating variables able to heighten or buffer adverse outcomes associated with exposure to sexism. The experimental work by Pacilli and colleagues (2019) represents a recent exception. These authors found that the relationship between exposure to HS during job selection and self-reported anxiety was moderated by women’s internalization of system justification beliefs in such a way that the less women justify the system, the more they experience anxiety as a result of exposure to a HS episode.

The Present Research

The primary aim of the current research was to investigate whether women’s level of ambivalent sexism moderates the relationship between exposure to workplace sexism and psychological distress. We performed two studies. In Study 1, we tested the effect of the exposure to sexism on female participants’ psychological distress. In Study 2, we analyzed how participants’ level of sexism moderated such link. Our main starting point was the work by Pacilli and colleagues (2019), who demonstrated that exposure to BS and HS during a job selection increased participants’ anxiety. However, and most importantly for our purpose, they found that not all women experienced anxiety to the same extent. On the contrary, those who endorsed low system justifying beliefs experienced greater anxiety when exposed to HS.

We aimed at extending this work in three ways. First, Pacilli and colleagues (2019) conducted their study within the Portuguese context. Portugal in 2019 ranked 35th in the Global Gender Gap Index, with a gender gap index equal to 0.744 (World Economic Forum 2020). We decided to probe the generalizability of their results to a context with a higher Gender Gap Index score. We focused on the Italian context. Italy is ranked 76th in Global Gender Gap Index, with a gender gap index equal to 0.707 (World Economic Forum 2020). Second, Pacilli and colleagues (2019) considered only anxiety as a measure of psychological distress. Based on Roccato and Russo (2017), who showed that the focus on both anxiety and depression enriches the picture of psychological distress, we took into account both these variables. Third, Pacilli and colleagues (2019) focused on system justification tendency as a possible moderator of the effects of sexism’s exposure. Instead, we focused on the endorsement of ambivalent sexism, to fill the gap stemming from the general paucity of research directly interested in sexism as a justifying ideology with a palliative function. Measuring and manipulating sexism in the same study gave us the possibility to analyze the relationship between two sides (individual and contextual) of the same construct.

In line with previous research on the detrimental effects of benevolent sexism (e.g., Dardenne et al. 2007; Grilli et al. 2020; Pacilli et al. 2019) we hypothesized that exposure to BS would increase anxiety and depression (H1 in Study 1 and Study 2). Further, we expected to replicate previous findings on detrimental effects of HS on women’s lives (e.g., Salomon et al. 2015; Schneider et al. 2001; Pacilli et al. 2019). Thus, we hypothesized that exposure to HS would increase anxiety and depression (H2 in Study 1 and Study 2).

As for the palliative function of BS endorsement, in line with the existing literature (e.g., Connelly and Heesacker 2012; Hammond and Sibley 2011; Napier et al. 2010) we expected that participants’ endorsement of BS would buffer the negative effects of experiencing a sexist environment, with women high versus low in BS reporting lower anxiety and depression when exposed to BS scenario (H3 in Study 2). As for the palliative function of HS, albeit literature did not consistently found support for buffering effect of HS (see Conelly and Heesacker 2012; Eliezer et al. 2011), in line with Pacilli and colleagues (2019) and with Vargas-Salfate (2017), we hypothesized that HS would play a palliative function, lowering anxiety and depression of participants exposed to HS scenario (H4 in Study 2).

The two studies were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, and fulfilled the ethical standard procedure recommended by the Italian Association of Psychology (AIP). The present research protocol was approved by the University of Torino Ethic Committee. Before taking part in the study, participants have been informed of their rights to refuse to participate in the study or to withdraw consent to participate at any time during the study without reprisal.

Study 1

Participants and Procedure

We performed an experimental vignette study designed on Dardenne et al.’s (2007) procedure. An a priori power analysis was conducted for sample size estimation (using G*Power 3.1; Faul et al. 2007). With an α = 0.05 and power = 0.95, the projected sample size needed to detect a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) for regression analysis was at least of 89 participants. One hundred and seventy-nine Italian adult women participated in the study (Mage = 24.17, SD = 9.45). The participants were recruited using a snowball procedure, starting from the members of the authors’ social networks. They completed the on-line questionnaire described below, presented as a simulation of a selection interview for a job in a chemical factory at present employing only male workers.

Measures and Procedure

Experimental Manipulation

Participants were randomly assigned to one out of three experimental conditions. In the neutral condition (n = 61), they just read the description of the job that they would have done if hired. In both sexist conditions, the participants read a brief statement reporting that the Italian parliament had recently approved a new law on gender quotas. In the hostile sexism condition (n = 52), the participants subsequently read, “Industry is now restricted to employ a given percentage of people of the weaker sex. I hope women here won’t be offended, they sometimes get so easily upset! If hired, you’ll work with men only, but don’t believe what those feminists are saying on TV, they probably exaggerate women’s situation in industry simply to get more favors!” After the introductory statement, the participants exposed to the benevolent sexist condition (n = 66) read the following paragraph: “Industry is now restricted to choose women instead of men in case of equal performance. You’ll work with men only, but don’t worry, they will cooperate and help you to get used to the job. They know that the new employee could be a woman, and they agreed to give you time and help.” This experimental manipulation showed to be effective in previous research performed in different national contexts (e.g., in Portugal, see Pacilli et al. 2019, in Belgium, see Dardenne et al. 2007, and in Italy, see Grilli et al. 2020).

Post-experimental Section

After the experimental manipulation, we asked participants to report the level of sexism that, in their opinion, characterized the chemical factory where they would have worked, if hired, using the 5-category item previously used by Pacilli et al. (2019): Do you think there is a prejudice against women in this company?. The five response categories ranged from 0 (= definitely not) to 4 (= definitely yes).

Subsequently, we measured participants’ level of anxiety using six 4-category items randomly chosen from the Italian version of Spielberger et al. (1983) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), form Y (Pedrabissi and Santinello 1989) (α = 0.88). In the original version of the scale, respondents are requested to report how they feel when answering the questionnaires, using items such as “I feel jittery”. Moreover, we measured participants’ level of depression using Pierfederici et al.’s (1982) Italian version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale (Radloff 1977) composed of 20 4-category items (α = 0.92). In its original version, respondents are asked to describe how often, compared to their usual standard, they felt in the week before the survey like described in items such as, I felt that I could not shake off the blues even with help from my family or friends. Participants were asked to answer the STAI and the CES-D Scale as they would have done if hired in the company described in the experimental manipulation. Previous research showed that these two scales, even modified as stated above, are efficient measures of anxiety and depression in experimental vignette studies (Roccato and Russo 2017).

A standard socio-demographic form followed. We computed the individual scores on all of these variables as the mean score of their items. After they filled in the questionnaire, the participants were accurately debriefed.

Data Analyses

After checking the effectiveness of our experimental manipulation using an ANOVA, we performed two linear regressions, respectively aimed at predicting participants’ anxiety and depression as a function of exposure to a hostile sexist message and to a benevolent sexist message. We used exposure to a neutral message as the reference category.

Results

A preliminary ANOVA showed that our experimental manipulation was effective. Indeed, the level of perceived sexism in the chemical company was highest among the participants exposed to the HS message (M = 3.89, SD = 0.32), lowest among the participants exposed to the neutral message (M = 0.70, SD = 0.94), and intermediate among the participants exposed to the BS message (M = 1.92, SD = 1.18), F(2,511) = 169.85, p < 0.001. Bonferroni post-hoc tests showed that all of these differences were significant with p < 0.001.

Table 1 shows the results of two linear regressions aimed at predicting participants’ level of anxiety (first three columns) and depression (second three columns) as a function of exposure to a HS message and to a BS message. In line with our expectations (H1 and H2) both exposure to a HS message and to a BS message fostered participants’ anxiety. The first path was significantly stronger than the second, t(354) = 4.40, p < 0.001. The same expected (H1 and H2) results stemmed as concerns the prediction of participants’ depression. Even in this case, the path linking exposure to a HS message and the dependent variable was stronger than that linking exposure to a BS message and participants’ depression, t(354) = 4.53, p < 0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that exposure to a benevolent and, especially, to a hostile sexist message impairs psychological well-being of female candidates to a work position, fostering their anxiety and their depression. These results are interesting per se, in that they show experimentally a link between the cultural characteristics of work environments and female workers’ well-being. Moreover, they help extend the extant knowledge on this topic in a twofold sense. First, we obtained them in Italy, i.e., in a country characterized by a stronger Gender Gap Index than that of the Portugal, where Pacilli and colleagues (2019) performed their study. Second, we showed that the pattern of results focused on participants’ anxiety can be generalized to another relevant kind of psychological distress, i.e., depression.

Although interesting, our results are focused exclusively on the effect that contextual characteristics exerted on women’s psychological well-being. However, consistent with Lewin’s (1936) classic idea that social psychological events usually depend on the interaction between the state of the person and the state of the environment where they live, some social psychologists showed experimentally that stable individual variables lead people to respond differently when they are exposed to the same environmental stimuli (e.g., Lavine et al. 2002; Mondak et al. 2010). In this line, we reasoned that it could have been interesting to extend Study 1′s approach by integrating participants’ levels of sexism in the predictive model. Thus, in Study 2 we extended our look on the links between experiencing a sexist context and women’s psychological distress, introducing participants’ pre-experimental level of HS and BS and their interactions with exposure to sexist messages among the predictors of anxiety and depression.

Study 2

Method

We used the same method we used in Study 1, with just three differences. First, before the experimental manipulation we measured participants’ individual level of HS and of BS. Second, we measured anxiety using the full scale and not a subsample of its items. Third, we predicted participants’ anxiety and depression via two hierarchic regression models, using exposure to sexism, individual sexism, and their interactions as predictors.

Participants and Procedure

An a priori power analysis was conducted for sample size estimation (using G*Power 3.1; Faul et al. 2007). With an α = 0.05 and power = 0.95, the projected sample size needed to detect a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) for our regression analyses was at least of 146 participants. We surveyed 514 Italian adult women who did not take part in Study 1 (Mage = 24.80, SD = 7.30). Starting from our social networks, we recruited the participants using a snowball procedure. The questionnaire, presented as a simulation of a selection interview for a job in a chemical factory at present employing only male workers, was administered on-line.

Measures and Procedure

Pre-experimental Section

Before the experimental manipulation, we measured participants’ levels of HS (α = 0.96) and of BS (α = 0.93) using Rollero et al.’s (2014) Italian version of Glick and Fiske’s (1997) Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI). The scale is composed of 22 5-category items such as, Many women are actually seeking special favors, such as hiring policies that favor them over men, under the guise of asking for ‘equality (aimed to measure HS) and Many women have a quality of purity that few men possess (aimed to measure BS).

Experimental Manipulation

After the ASI, the same experimental manipulation we used in Study 1 followed. One hundred and fifty-six participants were randomly assigned to the neutral condition, 172 to the hostile sexism condition, and 186 to the benevolent sexism condition.

Post-experimental Section

The post-experimental section was the same we used in Study 1, with the exception of the measure of anxiety. In this case, we measured anxiety using the full Italian version of Spielberger et al.’s (1983) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), form Y (Pedrabissi and Santinello 1989), composed of 13 4-category items (α = 0.96). Like in Study 1, we asked participants to answer the STAI and the CES-D as they would have done if hired and computed the individual scores on all of the scale we used as the mean score of their items. After they filled in the questionnaire, participants were accurately debriefed.

Data Analyses

After checking the effectiveness of our experimental manipulation using an ANOVA, we performed two moderated regressions, respectively aimed at predicting participants’ anxiety and depression as a function of exposure to a hostile sexist message, to a benevolent sexist message, of participants’ individual level of hostile sexism, of participant’s individual level of benevolent sexism, entered in Step 1, and of the first-order interactions between exposure to a hostile sexist message and participants’ individual level of hostile sexism on the one hand, and exposure to a benevolent sexist message and participants’ individual level of benevolent sexism on the other. We used the neutral experimental condition as the reference category. Before computing the interactions, we mean-centered participants’ hostile sexism and benevolent sexism scores, and recoded the dummies expressing the experimental conditions as − 1 and 1.

Results

A preliminary ANOVA showed that our experimental manipulation was effective. Indeed, the level of perceived sexism in the chemical company was highest among the participants exposed to HS message (M = 4.65, SD = 0.54), lowest among the participants exposed to the neutral message (M = 1.69, SD = 1.54), and intermediate among the participants exposed to the BS message (M = 3.83, SD = 1.16), F(2,511) = 420.58, p < 0.001. Bonferroni post-hoc tests showed that all of these differences were significant with p < 0.001.

Table 2 shows the results of our moderated regressions, respectively aimed to predict participants’ anxiety (first 3 columns) and depression (second 3 columns). In a convergent way, consistent with H1 and H2, both the exposure to a HS message and to a BS message heightened participants' distress. The stressful effect of the HS message was stronger than that of the BS message both as concerns anxiety, t(1024) = 7.60, p < 0.001, and as regards depression, t(1024) = 7.54, p < 0.001. The direct association between the individual level of sexism and the dependent variables was negative both as concerns anxiety and as regards depression. These associations were statistically equal, both as concerns anxiety, t(1024) = 1.18, p = 0.24, as regards depression, t(1024) = 0.47, p = 0.64.

Consistent with H3, the effect of the exposure to a BS message was fully significant among participants with low (− 1 SD) individual levels of BS, simple slope = 0.39, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, while it just approached statistical significance among those with high (+ 1 SD) levels of BS (H3), simple slope = 0.10, SE = 0.05, p = 0.05. Consistent with H4a, HS partially buffered the stressful effect of exposure to a hostile sexist message as concerns participants’ anxiety. Indeed, the effect of the exposure to a HS message was stronger among participants with low (− 1 SD) individual levels of HS, simple slope = 0.83, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001, than among those with high (+ 1 SD) levels of HS, simple slope = 0.53, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001. The difference between the two slopes was statistically significant, t(214) = 4.23, p < 0.001.

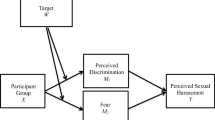

In line with our expectations (H3 and H4) the same moderation pattern stemmed as concerns depression. The effect of the exposure to a BS message (H3) was significant among participants with low (− 1 SD) levels of BS, simple slope = 0.32, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001, while it was just marginally significant among participants with high (+ 1 SD) individual levels of BS, simple slope = 0.07, SE = 0.08, p = 0.09. The effect exerted by exposure to a HS message (H4) on the dependent variable was stronger among participants with low (− 1 SD) individual levels of HS, simple slope = 0.61, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001, than among those with high (+ 1 SD) individual levels of HS, simple slope = 0.43, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001. The difference between the two slopes was statistically significant, t(214) = 3.09, p < 0.01. Figure 1 shows graphically the moderated effects we have detected.

Discussion

In Study 2, we confirmed and expanded the results from Study 1. First, we confirmed that exposure to sexism, especially to its hostile dimension, hampers women’s psychological well-being in the workplace. Second, we provided evidence for the palliative function of endorsement of both forms of sexism. Indeed, we showed that the endorsement of a sexist ideology hinders women’s psychological distress, both directly and partially buffering the negative effects of experiencing a sexist environment. In particular, we found that women endorsing lower levels of HS, when exposed to HS situation reported higher level of anxiety and depression compared to women with higher level of HS. As for benevolent dimension, we found that the effects of exposure to a BS situation were stronger among participants with low versus individual levels of BS.

General Discussion

There is near unanimous consensus that worldwide sexism affects women in many adverse ways and that it is one of the biggest obstacles to gender equality. As far as the workplace domain is concerned, research abundantly demonstrated that experiencing sexism undermines women’s psycho-physical well-being (e.g., McLaughlin et al. 2017; Pacilli et al. 2019; Rubin et al. 2019; Schneider et al. 2001). Further, another line of research demonstrated that despite sexism clearly works at women disadvantages, not only men but also women often tolerate and interiorize it (e.g., Glick et al. 2000; Kilianski and Rudman 1998). Although studies deeply analyzed the spread and the impact of sexism on women’s lives, research has not systematically investigated whether women would all be affected to the same extent by exposure to sexist manifestations, or endorsement of sexism moderates women’s reactions to such events. In the present research, we have built on this paucity by investigating whether the psychological distress associated with the exposure to workplace sexism would vary according to women’s endorsement of ambivalent sexism.

In line with the literature (e.g., Pacilli et al. 2019; Schneider et al. 2001), in both studies we confirmed the detrimental impacts of workplace sexism on women’s well-being. In particular, we found that exposure to HS during a job selection increased women’s level of anxiety and depression. Further, even exposure to BS job selection fostered anxiety and depression. In both studies, the adverse emotional reactions to sexism were stronger for women exposed to HS (vs. BS). This could be due to the fact that the expression of HS being more blatant and denigrating, is easily recognized as a discrimination and is more offensive and thus fosters a stronger reaction as compared to BS which is more subtle and patronizing in suggesting women’s inferiority.

Regarding the moderating role of endorsement of sexism, we provide evidence for the palliative function of ambivalent sexism. As far as BS is concerned, results revealed that women’s endorsement of BS fully buffered the adverse reaction to exposure to BS situation, with women lower in BS experiencing greater anxiety and depression. This result is in line with, and extend, previous research that demonstrated that women high in benevolent sexism and who tend to justify the system express greater life satisfaction (Connelly and Heesacker 2012; Hammond and Sibley 2011; Napier et al. 2010). As for exposure to HS, we found that adverse emotional reaction was partially buffered by endorsement of HS, with women lower in HS experiencing greater anxiety and depression than women higher in HS. This result is in line with recent evidence on the palliative function of ideologies in the domain of sexism. Indeed, while Vargas-Salfate (2017) demonstrated that similarly to BS, even HS could function as an adaptive strategy that fosters life satisfaction, Pacilli and colleagues (2019) found that women low in system justifying beliefs, when exposed to HS, reported higher anxiety. However, other research on the palliative function of HS offered a different picture of results. On the one hand, Conelly and Heesacker (2012) did not find a significant association between HS and life satisfaction. On the other hand, Eliezer and colleagues (2011) demonstrated that when one is exposed to a hostile event, the endorsement of system-justifying beliefs function as a stressor, rather than as a coping resource.

The mixed evidence, alongside with our results that highlighted a partial buffering effect of HS, might be explained based on some specific features of the two forms of sexism. BS offers people a palatable rationale for gender inequality due to its subtle and apparently flattering manifestations. Stressing the complementarity character of stereotypical gender roles BS provided women with a positive social identity (Jost and Kay 2005; Conelly and Heesacker 2012). Consistently, if women are considered inferior to men in some domains (i.e., strength and competence), they are considered superior to me in other domains (i.e., care and interpersonal warmth: see Connelly and Heesacker 2012). Thus, promoting the idea of a compensatory and balanced division of roles between men and women, BS suggests that society operates as it should, promoting the acceptance of the status quo and even providing a coping resource to deal with inequalities (Conelly and Heesacker 2012). In contrast, the fact that HS openly communicates an antipathy towards women without flattering compensations makes the justification of the fairness of the system harder. However, women endorsement of HS means that women are convinced of their inferiority and of the fact that they deserve disadvantaged positions within the society (Vargas-Salfate 2017). The internalization of inferiority is confirmed by research within the depressed entitlement paradigm showing that despite independent judges rated a written work by men and women as equal, women rated their own work as poorer and as deserving a lower payment when compared to men (Jost 1997). Thus, internalizing the inferiority leads people to greater acceptance of unfairness and greater justification of legitimacy of the system. Consistently, we found that women with lower level of HS experienced greater anxiety and depression when exposed to HS situation, plausibly because they are not ideologically equipped to justify the discrimination.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our research extended the knowledge on the palliative function of sexist ideology providing evidence of the interaction between sexism endorsement and exposure to workplace sexism on women psychological well-being. However, there are also some limitations to the present research. One limitation lies in the fact that we measured the immediate psychological reaction derived from exposure to workplace sexism, disregarding possible long-term effects. Future research could investigate whether the endorsement of sexism protects women from negative outcomes in the long-term too, or whether women, regardless of their ideological standpoints, would report long-term health impairment as a consequence of exposure to sexist events. Another limitation is the fact that we did not investigate whether anxiety and depression as a response to unfair event would in turn produce other consequences for women. Indeed, the literature demonstrated that exposure to unfair events in the workplace is associated with engagement in unhealthy behaviors and work productivity impairment (Combs and Milosevic 2016). In this regard, future research could analyze whether anxiety and depression as a result of exposure to workplace sexism would impact women’s performance and healthy life style according to their endorsement of sexism. We assessed the self-reported state anxiety and depression as responses to the exposure to a sexist event in workplace. Future research could go a step further adopting psycho-physiological measures of individual's stressful reactions. Further, we did not control for participants’ trait dimensions of these constructs. Future research could include trait dimension of anxiety and depression not only to control for their effect but even to explore whether they interact with psychological response to unfair events.

Finally, our results highlight the relevance of considering the outcomes of events at the light of interaction between the state of the person and the state of the environment. We investigated such an interactive effect adopting an experimental approach. Future research could go a step further by investigating such an effect adopting a cross-cultural multilevel approach, with a particular attention to the interaction between country’s gender gap index and inhabitants’ endorsement of sexism.

Conclusion

The adverse outcomes of sexism on women’s lives has been widely investigated. However, a systematic understanding of the role played by women’s ideological standpoints in shaping psychological outcomes associated with exposure to gender-based discrimination is still lacking. Our results indicated that women experienced anxiety and depression as a result of the exposure to BS and HS, and, most importantly for our purpose, that women who poorly endorse sexist beliefs are those who experience the more adverse psychological reactions when exposed to sexism in workplace.

Availability of Data and Material (Data Transparency)

Electronic copies of the anonymized raw data, related coding information, and all materials used to collect data will be made available upon request.

References

Abrams, D., Viki, G. T., Masser, B., & Bohner, G. (2003). Perceptions of stranger and acquaintance rape: The role of benevolent and hostile sexism in victim blame and rape proclivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.111.

Barreto, M., & Ellemers, N. (2005a). The perils of political correctness: Men’s and women’s responses to old-fashioned and modern sexist views. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68, 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250506800106.

Barreto, M., & Ellemers, N. (2005b). The burden of benevolent sexism: How it contributes to the maintenance of gender inequalities. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 633–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.270.

Beaton, A. M., Tougas, F., & Joly, S. (1996). Neosexism Among Male Managers: Is It a Matter of Numbers?1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26(24), 2189–2203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01795.x.

Becker, J. C., & Wright, S. C. (2011). Yet another dark side of chivalry: Benevolent sexism undermines and hostile sexism motivates collective action for social change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022615.

Booth, A. L., Francesconi, M., & Frank, J. (2003). A sticky floors model of promotion, pay, and gender. European Economic Review, 47(2), 295–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00197-0.

Borrell, C., Artazcoz, L., Gil-González, D., Pérez, G., Rohlfs, I., & Pérez, K. (2010). Perceived sexism as a health determinant in Spain. Journal of Women’s Health, 19(4), 741–750. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2009.1594.

Chan, D. K. S., Lam, C. B., Chow, S. Y., & Cheung, S. F. (2008). Examining the job-related, psychological, and physical outcomes of workplace sexual harassment: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 362–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00451.x.

Cikara, M., Eberhardt, J. L., & Fiske, S. T. (2011). From Agents to Objects: Sexist Attitudes and Neural Responses to Sexualized Targets. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23(3), 540–551. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2010.21497.

Combs, G. M., & Milosevic, I. (2016). Workplace discrimination and the wellbeing of minority women: Overview prospects and implications. In M. L. Connerley & J. Wu (Eds.), Handbook on well-being of working women (pp. 17–31). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Connelly, K., & Heesacker, M. (2012). Why is benevolent sexism appealing? Associations with system justification and life satisfaction. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36(4), 432–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684312456369.

Dardenne, B., Dumont, M., & Bollier, T. (2007). Insidious dangers of benevolent sexism: Consequences for women’s performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 764–779. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.764.

Dumont, M., Sarlet, M., & Dardenne, B. (2010). Be too kind to a woman, she’ll feel incompetent: Benevolent sexism shifts selfconstrual and autobiographical memories toward incompetence. Sex Roles, 62, 545–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9582-4.

Eliezer, D., Townsend, S. S., Sawyer, P. J., Major, B., & Mendes, W. B. (2011). System-justifying beliefs moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and resting blood pressure. Social Cognition, 29, 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2011.29.3.303.

Elliott, J. R., & Smith, R. A. (2004). Race, Gender, and Workplace Power. American Sociological Review, 69(3), 365–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240406900303.

Equal Measures 30 (2019). Harnessing the power of data for gender equality: Introducing the 2019 EM2030 SDG Gender Index. Retrieved from: https://data.em2030.org/2019-global-report/

European Institute for Gender Equality (2019). Gender Equality Index 2019 Work-life balance. Retrieved from: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-equality-index-2019-work-life-balance

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1997). Hostile and benevolent sexism: Measuring ambivalent sexist attitudes toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(1), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00104.x.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.109.

Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J., Abrams, D., Masser, B., et al. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 763–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.763.

Glick, P., Sakalli-Ugurlu, N., Ferreira, M. C., & Souza, M. A. (2002). Ambivalent sexism and attitudes toward wife abuse in Turkey and Brazil. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 292–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00068.

Grilli, S., Pacilli, M. G., & Roccato, M. (2020). Exposure to sexism impairs women’s writing skills even before their evaluation. Sexuality & Culture. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09722-8.

Hammond, M. D., & Sibley, C. G. (2011). Why are benevolent sexists happier? Sex Roles, 65(5–6), 332–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0017-2.

Jost, J., & Hunyady, O. (2003). The psychology of system justification and the palliative function of ideology. European Review of Social Psychology, 13, 111–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00377.x.

Jost, J. T. (1997). An experimental replication of the depressed entitlement effect among women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00120.x.

Jost, J. T., & Banaji, M. R. (1994). The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1994.tb01008.x.

Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychology, 25, 881–919. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00402.x.

Jost, J. T., & Kay, A. C. (2005). Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: Consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 498–509. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.498.

Kilianski, S. E., & Rudman, L. A. (1998). Wanting it both ways: Do women approve of benevolent sexism? Sex roles, 39(5–6), 333–352. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018814924402.

Lavine, H., Lodge, M., Polichak, J., & Taber, C. (2002). Explicating the black box through experimentations: Studies of authoritarianism and threat. Political Analysis, 10(4), 343–361. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/10.4.343.

Levine, C. S., Basu, D., & Chen, E. (2017). Just world beliefs are associated with lower levels of metabolic risk and inflammation and better sleep after an unfair event. Journal of Personality, 85, 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12236.

Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of topological psychology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Manuel, S. K., Howansky, K., Chaney, K. E., & Sanchez, D. T. (2017). No rest for the stigmatized: A model of organizational health and workplace sexism (OHWS). Sex Roles, 77(9–10), 697–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.046.

McLaughlin, H., Uggen, C., & Blackstone, A. (2017). The economic and career effects of sexual harassment on working women. Gender & Society, 31(3), 333–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243217704631.

Mondak, J. J., Hibbing, M. V., Canache, D., Seligson, M. A., & Anderson, M. R. (2010). Personality and civic engagement: An integrative framework for the study of trait effects on political behavior. American Political Science Review, 104, 85–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409990359.

Napier, J. L., Thorisdottir, H., & Jost, J. T. (2010). The joy of sexism? A multinational investigation of hostile and benevolent justifications for gender inequality and their relations to subjective well-being. Sex Roles, 62, 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9712-7.

Pacilli, M. G., Spaccatini, F., Giovannelli, I., Centrone, D., & Roccato, M. (2019). System Justification moderates the relation between hostile (but not benevolent) sexism in the workplace and state anxiety: An experimental study. Journal of Social Psychology, 159, 474–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2018.1503993.

Pedrabissi, L., & Santinello, M. (1989). Nuova versione italiana dello S.T.A.I – Forma Y [New Italian version of the S.T.A.I., Form Y]. Firenze: Organizzazioni Speciali.

Penone, G., & Spaccatini, F. (2019). Attribution of blame to gender violence victims: A literature review of antecedents, consequences and measures of victim blame. Psicologia sociale, 14(2), 133–165. https://doi.org/10.1482/94264.

Pierfederici, A., Fava, G. A., Munari, F., Rossi, N., Baldaro, B., Pasquali Evangelisti, L., et al. (1982). Validazione italiana del CES-D per la misurazione della depressione [Italian validation of the CES-D measure of depression]. In R. Canestrari (Ed.), Nuovi metodi in psicometria [New methods in psychometry] (pp. 95–103). Firenze: Organizzazioni Speciali.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306.

Roccato, M., & Russo, S. (2017). Right-wing authoritarianism, societal threat to safety, and psychological distress. European Journal of Social Psychology¸47, 600–610. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2236

Rollero, C., Glick, P., & Tartaglia, S. (2014). Psychometric properties of short versions of the ambivalent sexism inventory and ambivalence toward men inventory. Testing, Psychometry & Methogology, 21, 149–159. https://doi.org/10.4473/TPM21.2.3.

Rubin, M., Paolini, S., Subašić, E., & Giacomini, A. (2019). A confirmatory study of the relations between workplace sexism, sense of belonging, mental health, and job satisfaction among women in male-dominated industries. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 49(5), 267–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12577.

Salomon, K., Burgess, K. D., & Bosson, J. K. (2015). Flash fire and slow burn: Women’s cardiovascular reactivity and recovery following hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 144, 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000061.

Schneider, K. T., Tomaka, J., & Palacios, R. (2001). Women’s cognitive, affective, and physiological reactions to a male coworker’s sexist behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31, 1995–2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb00161.x.

Sojo, V. E., Wood, R. E., & Genat, A. E. (2016). Harmful workplace experiences and women’s occupational well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40, 10–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684315599346.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Swim, J. K., Aikin, K. J., Hall, W. S., & Hunter, B. A. (1995). Sexism and racism: Old-fashioned and modern prejudices. Journal of personality and social psychology, 68(2), 199. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.2.199.

Tougas, F., Brown, R., Beaton, A. M., & St-Pierre, L. (1999). Neosexism among women: The role of personally experienced social mobility attempts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(12), 1487–1497. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672992510005.

Vargas-Salfate, S. (2017). The palliative function of hostile sexism among high and low-status Chilean students. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1733. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01733.

Wakslak, C. J., Jost, J. T., Tyler, T. R., & Chen, E. S. (2007). Moral outrage mediates the dampening effect of system justification on support for redistributive social policies. Psychological Science, 18, 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01887.x.

World Economic Forum. (2020). Global Gender Gap Report 2020. Retrieved from: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf

Funding

This work was not supported by any Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in these studies were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The present research protocol was approved by the University of Torino Ethic Committee [Protocol Number: 441505].

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the studies.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spaccatini, F., Roccato, M. The Palliative Function of Sexism: Individual Sexism Buffers the Relationship Between Exposure to Workplace Sexism and Psychological Distress. Sexuality & Culture 25, 767–785 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09793-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09793-7