Abstract

Using thematic analysis of interview data, the present study assessed teen girls’ and young adult women’s attitudes toward posting sexualized profile photos on Facebook. In addition, sexualization behaviors depicted in participants’ profile photos were examined. Participants overwhelmingly disapproved (either in a reluctant or a clear manner) of posting a profile photo of oneself in underwear on social media. A somewhat different pattern emerged in attitudes about posting a swimsuit photo in which specific conditions were laid out determining whether swimsuit photos were acceptable or not. Sexualization cues in profile photos were generally low. Findings suggest that posting a sexualized photo on social media comes with relational costs for girls and women. Strategies for educating young people about new media use and sexualization are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The sexualization of girls and women is widespread in today’s media environment. Three major reports from the UK, U.S., and Australia have documented its prevalence and negative consequences (American Psychological Association [APA] 2007; Papadopoulos 2010; Rush and La Nauze 2006). It is, therefore, well-documented that girls/women routinely see sexiness encouraged and rewarded through mass media. New media, such as social media, which are user-created and highly popular among young people, are also a context for sexualization (Manago 2013; Ringrose 2011; Ringrose et al. 2013). Recent evidence demonstrates that teen girls witness and enact sexiness on social media (Ringrose 2011). Yet, girls and young women risk negative social consequences in portraying themselves in a sexualized manner online (Bailey et al. 2013; Baumgartner et al. 2015; Daniels and Zurbriggen 2016; Manago et al. 2008). Thus, girls/young women are in the paradoxical position of experiencing social and cultural pressure to be sexy while simultaneously risking penalties for this behavior. The present study examined adolescent girls’ and young adult women’s attitudes about themselves and peers posting sexualized photos on social media. In addition, we investigated sexualization behaviors depicted in participants’ own profile photos. Our aim was to better understand attitudes and behaviors related to sexualization in new media from the perspective of girls and young women at different stages of development. The combination of attitudinal and behavioral data is a unique contribution of the present study.

Sexualized Culture

Renewed concerns about the impact of sexualization in the media and consumer culture on girls and young women have been voiced in academic circles and in popular culture over the past 10–15 years. Researchers have documented increases in sexualization in media aimed at young people (APA 2007; Graff et al. 2013; Hatton and Trautner 2011), and journalists have brought the prevalence of pornography use (Paul 2005) and raunch culture to the public’s attention (Levy 2005). More recently, scholars have debated whether sexual agency or empowerment among adolescent girls and young women is possible in Western contexts that objectify women’s bodies as a dominant practice (see special issue Sex Roles 2012; Bay-Cheng 2012; Gill 2012; Lamb and Peterson 2012; Murnen and Smolak 2012; Tolman 2012). On one side of the debate are proponents of the view that the current sexualized climate affords girls and women opportunities to express themselves sexually in ways that they find subjectively powerful and pleasurable which is empowering (e.g., Peterson 2010). On the other side of the debate are those who argue that equating subjective pleasure with empowerment ignores cultural practices, including sexism and patriarchy, as well as marketplace forces that routinely objectify and commodify women’s bodies (e.g., Levy 2005; Lamb 2010). Thus, an individual may experience sexualized behavior (e.g., pole dancing) as pleasurable, but the broader society reads such behavior through the lens of the male gaze and denigrates women engaged in sexualized behavior as mere sexual objects. Whereas theorizing about this issue is critically important, in the present study, we brought adolescent girls and young women’s voices to the fore by investigating their attitudes about sexualization through the use of interview data.

In the present study, we also brought the issue of sexualization to a context that is highly important to young people—social media. Approximately 89 % of U.S. teens use social media with Facebook as the most popular site used by 71 % of teens (Lenhart 2015). Similar patterns are true for young adults (ages 18–29) (Social networking fact sheet 2014). Further, social media play a central role in peer relationships among adolescents and young adults (boyd 2014; Pempek et al. 2009; Special and Li-Barber 2012) including for use in initiating, reinforcing, and dissolving dating relationships (Baker and Carreño 2015; Subrahmanyam and Greenfield 2008). Therefore, social media are integral to young people’s peer and romantic relationships. Accordingly, social media are contexts in which youth attempt to attract the interest of their peers, possibly through self-sexualizing behaviors such as posting photos of sexualized body parts (see Manago 2013; Ringrose 2011).

Prior research with adult women (mean age = 24) has demonstrated that self-sexualizing acts can be read as either empowered or as needy grabs for attention by women with poor self-esteem, suggesting that the meaning associated with sexualized behavior is subject to varying interpretations (Thompson and Donaghue 2014). Thus, there is no common understanding of what constitutes an acceptable versus problematic self-sexualizing behavior. In the present study, we investigated girls’ and young women’s attitudes toward two behaviors that could be perceived as acceptable or problematic self-sexualizing behavior—posting a swimsuit photo on social media and posting an underwear photo on social media.

Objectification Theory

Motives for engaging in self-sexualizing behaviors in online spaces and attitudes toward girls/women who do so should be considered in light of cultural attitudes toward women’s bodies. Objectification theory argues that Western societies routinely sexually objectify the female body (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997; McKinley and Hyde 1996). Women’s bodies are scrutinized as objects for the pleasure and evaluation of others, specifically men (and boys). This sexual objectification can occur within interpersonal and social encounters as well as through experiences with visual media. As a result of this cultural pressure, many girls and women self-objectify, focusing on how their bodies appear rather than what they can do. The extent to which a society endorses sexual objectification is related to the likelihood of girls/women engaging in self-sexualizing practices, such as posting sexualized photos on social media, intended to increase their heterosexual appeal regardless of possible costs associated with enacting a sexualized appearance (Smolak and Murnen 2011).

To date, research has primarily focused on negative attitudes (e.g., less competent, less determined, less intelligent, less agentic, having less self-respect, being less fully human, less moral, and being more sexually experienced) levied against women and girls depicted in a sexualized manner (Cikara et al. 2011; Daniels 2012; Daniels and Wartena 2011; Graff et al. 2012; Gurung and Chrouser 2007; Heflick and Goldenberg 2009; Loughnan et al. 2010). Only a few studies have examined the relationship between holding sexualized beliefs and girls’ self-perceptions and behaviors. McKenney and Bigler (2014a) found that girls (ages 10–15) high in internalized sexualization (defined as the belief that being sexually attractive to males is an important part of the self) wore more sexualized clothing (Study 1) and reported higher levels of body surveillance and body shame (Study 2) compared to girls low in internalized sexualization. Girls high in internalized sexualization also earned lower grades and standardized test scores than their peers (McKenney and Bigler 2014b; Study 1) and prioritized physical appearance over studying in a behavioral task (Study 2). Together these findings demonstrate clear costs to girls/women who are portrayed in a sexualized way and costs to girls who hold beliefs that their sexual attractiveness is centrally important. In the present study, we examined how sexualized behavior is perceived in a context important to young people, social media.

Sexualized Media Environment

Today’s mass media routinely present sexually objectified portrayals of women (see Collins 2011 for a review). For example, in a study of the top 20 best-selling video games in the U.S., Downs and Smith (2010) found that female characters were significantly more likely to be shown partially nude, depicted wearing sexually revealing and inappropriate clothing, and possessing unrealistic body proportions compared to male characters. Similar patterns have been found in music videos where female artists are more likely to be sexually objectified than male artists are in pop, hip hop, and R&B genres (Aubrey and Frisby 2011). This is especially true for Black female artists (Frisby and Aubrey 2012; Ward et al. 2013). Women are likely to be sexually objectified even in children’s television shows and family films (Smith et al. 2012) as well as sport media (Daniels and LaVoi 2013). At this point, the number of studies documenting this phenomenon in mass media is substantial (see APA 2007). Far less research has been conducted on the prevalence of sexualization on social media. We located just two content analyses of sexualization on social media. Hall et al. (2012) analyzed 24,000 MySpace.com profile photos belonging to women ages 18–49. Overall, rates of self-sexualization were fairly low with revealing clothing being the most common practice (15 % of sample). Of note, data were collected in the winter and it is not clear whether time of year impacted the findings. Self-sexualization was more common among young women compared to older women. In a study of 400 profiles on a popular teen chat site, Kapidzic and Herring (2015) found that teen girls were more likely to post pictures in which they were wearing revealing dress or were partially undressed (48.7 %) than were boys (25.8 %). Together these patterns reveal that young people today regularly see girls/women portrayed in sexualized ways in both traditional and new media they consume on a daily basis.

A substantial body of evidence also exists that demonstrates relationships between consuming sexually objectifying mass media and negative outcomes including stereotypical attitudes toward gender roles; stronger acceptance of the belief that women are sex objects; more accepting attitudes toward sexual harassment, date rape, and teen dating violence; and body image concerns among girls and women (for reviews see Ward 2016; Ward et al. 2013, 2014). We located just one study examining the relationship between exposure to sexualization on social media and adolescent outcomes. van Oosten et al. (2015) found that exposure to others’ sexy self-presentations was unrelated to Dutch teens’ sexual attitudes, but was related to their sexual behaviors. However, more research is clearly necessary to understand the impact exposure to sexualization on social media has on young people especially given their heavy engagement with this media form and the potential for sexualization to occur in new and dynamic ways in this context. For example, until recently there was an iPhone app, called Pikinis, which identified people individuals designated as friends on Facebook who had swimsuit photos on their profile (Notopoulos 2015). The app was shut down for violating Facebook’s terms of use. Nevertheless, this app as well as others, such as Kik, Yik Yak, and Snapchat known as places for sexual interaction among young people (Sales 2016), demonstrate how evolving technology could create additional pressure on girls and young women, specifically, to engage in self-sexualization in new media forms.

Age Differences

Self-objectification is apparent in some girls as early as grade school (Grabe et al. 2007; Lindberg et al. 2006). Despite these findings, the developmental trajectories of self-objectification and self-sexualization have not yet been articulated in the research literature (see Smolak and Murnen 2011). For example, it is not clear whether self-objectification spikes during particular periods of development, perhaps at the onset of puberty, and then attenuates, or whether there is a linear increase in self-objectification over time. Similarly, perhaps self-sexualization increases at specific points in adolescence, such as the onset of dating, and then varies with relationship status. These questions should be addressed in future research. In the present study, we examined possible age differences in girls/young women’s attitudes toward sexualized content on social media.

Present Study

Through the use of interviews, the present study investigated teen girls’ and young adult women’s attitudes toward the use of sexualized photos on social media. We investigated attitudes toward two types of photos: (a) a swimsuit photo, and (b) an underwear photo. In addition, we examined sexualization behaviors depicted in participants’ own profile photos. It is clear that there is significant sociocultural pressure on girls and young adult women to portray themselves in sexualized ways in the U.S., especially from the mass media and consumer culture. Yet, there are also clear costs to doing so. Accordingly, we did not set forth a priori predictions about participants’ attitudes. Instead, we used a methodology that would allow us to listen to girls’ and young women’s voices on an issue they contend with regularly as a function of being a girl/woman in the U.S.—sexualization. In addition, we framed this issue in a context that is a central feature of young people’s lives—social media. Finally, we examined possible age differences.

Method

Participants

A convenience sample of 112 adolescent girls and young adult women (13–25 years old, M = 18.56, SD = 3.40) was used in the present study which is part of a larger investigation assessing adolescent girls and young adult women’s social networking practices. We grouped participants into three age groups including early teens (13–16 year-olds; n = 41), late teens (17–20 year-olds; n = 36), and young women (21–25 year-olds; n = 35). Participants were recruited in Central Oregon through announcements at a youth-serving summer program, in Psychology courses at a high school and two colleges, and through a posting on a local page of Craigslist.com. Because the number of individuals who qualified for the study (girls and women ages 13–25 who use Facebook) was unknown, it was not possible to accurately report response rates.

Participants were primarily European-American (70.5 %) with 6.3 % Latina, 0.9 % Native American/American Indian, 0.9 % African-American/Black, 0.9 % Asian American/Pacific Islander, 0.9 % other ethnicity, and 19.6 % reporting multiple ethnicities. The sample is somewhat more diverse than the population of the county in which the data were collected. In the 2013 census, 88.1 % of individuals in this county reported being White alone, not Latino/Hispanic (U.S. Census Bureau 2015).

Adolescents were asked to report their parents’ level of education. The average parental level of education was some college including community college for both mothers and fathers (n = 4 participants reported not knowing their mothers’ level of education; n = 2 participants reported not having a father; n = 9 participants reported not knowing their fathers’ level of education). Level of education varied among the young adult women. Most reported that they attended some college including community college (n = 32) (n = 1 attended some high school; n = 8 graduated high school; n = 7 graduated from a 4-year college; n = 4 postgraduate study or degree).

After the study procedure was explained to all participants, girls gave assent and young adult women gave consent to participate. Participants under 18 were required to obtain parental consent in advance of participation in the study. Participants were compensated with a gift certificate to a local movie theater for volunteering their time.

Procedure

In a private room on a college campus in 2011–2012, participants completed an online survey while alone and then were interviewed individually by a member of the research team (n = 5 undergraduate women and the first author). In addition, the information page of their Facebook profile and the album of profile photos were saved via screenshots (n = 3 participants did not want their Facebook profiles saved for the study; these participants were excluded from analyses of profile photos). Note that Facebook changed from an older format to the current Timeline format during the end of data collection. A minority of participants had the Timeline format when they were interviewed (n = 13). Interview questions about posting photos in a swimsuit or underwear on Facebook constitute the central focus of the present study; these questions were posed to all participants regardless of whether they wanted their profile photos saved.

Measures

Facebook Usage

Participants were asked to report their Facebook usage with three items. They were asked about the frequency of their use with the item “how many days during a typical week do you log-on to Facebook?” and the intensity of their use with two items including “how many minutes per day do you spend on Facebook on a weekday” and “how many minutes per day do you spend on Facebook on weekend days.” All three items were presented in an open-ended format so that participants typed in their responses.

Demographics

Participants were asked to report their age, ethnicity, whether they were a high school student or not, and their/their parents’ level of education.

Interview Questions

Participants were asked the following five questions: (a) Why do teen girls/young women use swimsuit or underwear pictures as their profile photo?; (b) Do you think it’s OK to post a profile photo of yourself in a swimsuit?; (c) Do you think it’s OK to post a profile photo of yourself in underwear?; (d) What is your opinion of another girl/young woman who would post a profile photo of herself in a swimsuit?; and (e) What is your opinion of another girl/young woman who would post a profile photo of herself in underwear?

Coding of Interviews

Themes for the content of interviews were inductively-derived (Boyatzis 1998; Braun and Clarke 2006) (the coding scheme is available by request from the first author). An undergraduate research assistant reviewed all of the interviews and identified themes present in responses. The first author then created definitions of these themes and trained coders using ten interviews that are not included in the present sample. Coders were two female undergraduate research assistants. Disagreements in coding were resolved through discussion. Inter-rater reliability within teams was calculated using the kappa statistic.

Responses to four sexualization questions were coded into five categories. Questions include: (a) Do you think it’s OK to post a profile photo of yourself in a swimsuit?; (b) Do you think it’s OK to post a profile photo of yourself in underwear?; (c) What is your opinion of another girl/young woman who would post a profile photo of herself in a swimsuit? and; (d) What is your opinion of another girl/young woman who would post a profile photo of herself in underwear? Response categories include: unclear judgment (0) which includes statements in which the participant’s attitude about posting a type of photo is not clear; approval (1) which includes statements that the photo is OK or the participant has no judgment/is indifferent; conditional approval/disapproval (2) which includes statements in which the participant states particular conditions under which a photo is OK (e.g., with my friends at the lake) and contrasts that with conditions under which a photo is not OK (e.g., posed in the bathroom trying to look sexy); reluctant disapproval (3) which includes statements that express disapproval but hedge the judgment in some way (e.g., she probably doesn’t have good guidance at home) or states that the photo is OK but I would not post such a photo; and, clear disapproval (4) which includes statements that express clear disapproval of the photo with no softening of this judgment.

Participants’ rationales of their judgments about the photos were also coded. Only themes present in at least 10 participants’ responses are described below. Themes were coded as present (1) or absent (0). For the inappropriate theme, the participant stated that a swimsuit/underwear photo is inappropriate, weird, and/or sends a bad message. For the privacy theme, the participant stated that a swimsuit/underwear photo is meant to be private and/or for the bedroom; implies that social networking sites (SNS) are not private; or states she does not want to reveal/show her body. For the seeking sexual attention theme, the participant stated that posting a swimsuit/underwear photo is asking for sexualized attention from men/boys or attracts the wrong kind of attention. For the general attention theme, the participant stated that posting a swimsuit/underwear photo is asking for attention/positive feedback from others. For the character indictment theme, the participant made a negative attribution about moral character based on a swimsuit/underwear photo (e.g., she is a slut), and/or described how the photo would cause a loss of respect for the person and possibly termination of a relationship. For the relationship concern theme, the participant referenced a romantic partner’s or family member’s disapproval. For the body image concern theme, the participant stated that she is not confident about/comfortable with her body. For the body image confidence theme, the participant stated that a girl or woman must have confidence in her body to post a swimsuit/underwear photo. Finally, for the respect theme, the participant stated that a swimsuit/underwear photo is disrespectful to oneself.

A similar approach was taken to coding an introductory question about motives for sexualization intended to warm participants up to the topic before asking about their own behaviors and attitudes toward other girls/women. In responses to the question “why do teen girls/young women use swimsuit or underwear pictures as their profile photo?,” just two themes were present in at least 10 participants’ responses. For the attention/exposure theme, the participant stated that the photo was selected to get sexual interest/attention from boys/men, to show off her sexuality, to show off/get positive feedback about her body, or to get attention in general. For the negative self-image theme, the participant stated that the girl/young woman is insecure or has low self-esteem.

Finally, responses across all five interview questions were coded for two global evaluations. For the long-term implications theme, a participant discussed a long-term consequence of Facebook behavior (e.g., might be embarrassed later about what you posted when you were 18). For the structural/feminist analysis theme, a participant discussed the impact of cultural norms on girls’/young women’s Facebook behavior (e.g., sexual double standard that penalizes women for being sexual while praising men for the same behavior).

Coding of Photos

A sample of each participant’s profile photos was coded for the content of the photo and sexualization cues for photos that featured the participant. The profile photo currently in use and a sample of up to 10 additional photos were coded (fewer than 10 photos were coded for participants who had fewer than 10 photos in their profile photo album). The sample was created by numbering all of the photos in a participant’s profile photo album and using a random number generator to select up to 10 different photos. Coders for content and sexualization cues were four female undergraduate research assistants (not involved in the coding of the interview questions) who worked in teams of two; each team coded half of the sample. Inter-rater reliability within teams was calculated using the kappa statistic. Kappas are reported as a range representing the two teams. Disagreements in coding were resolved through discussion. Inter-rater reliability across teams was assessed by having both teams code a subset of the dataset (n = 107 photos). Inter-rater reliability was below threshold (κ = .70) for two coding categories (mouth and pose). Therefore, the first author and a female graduate student coded 100 % of the sample for those categories (kappas for these categories reported below are from this coding). Disagreements in coding were resolved through discussion.

Themes for the content of the photos were primarily inductively-derived (Boyatzis 1998; Braun and Clarke 2006). An undergraduate research assistant reviewed all of the photos in the dataset and identified patterns in the types of photos, e.g., photo of the self, photo of the self in a group of people. In addition, because of their relevance to objectification theory we created three additional categories including (a) whether the photo depicted the participant actively engaged in a physical activity; (b) whether the photo depicted the participant engaged in a hobby, and; (c) whether the photo depicted the participant in graduation regalia. These photos depict: (a) what one can do with one’s body, (b) who one is as a person, and (c) what one has achieved; all of which represent non-objectified portrayals of the self. Non-objectified portrayals contrast with objectified portrayals, which focus on how one appears. Definitions of themes were created and coders were trained on photos from 10 individuals not included in the present sample. Themes present in at least 10 % of photos are described and reported. Inter-rater reliability for the content theme ranged from κ = .90–.93.

For photos depicting the participant, sexualization cues were coded using a modified version of Hatton and Trautner’s (2011) coding scheme (available by request from the first author). Hatton and Trautner’s (2011) study examined sexualization cues on the covers of Rolling Stone magazine. Five characteristics were coded including head versus body shot, pose, clothing/nudity, touch, and mouth. Higher scores represent increased objectification.

Head versus body shot (κ = .90–.93) was coded as head only (0 points), full or 3/4th body (1), above the waist only (2), below the waist only (3), and body part (4). Scoring for objectification increased as the photo progressively focused more on the target’s body and ultimately eliminated her personhood by excluding her face.

Pose (κ = .85) was coded as non-sexual (0), e.g., standing upright; somewhat sexual (1), e.g., suggestive head tilt; and very sexual (2), e.g., sitting with legs spread open.

Clothing/nudity (κ = .80–.85) was coded as unrevealing (0), e.g., body is completely covered; slightly revealing (1), e.g., shirt with modestly low neckline; somewhat revealing (2), e.g., short shorts; highly revealing (3), e.g., midriff showing; bikini/lingerie body not clearly visible (4), e.g., photo is from a distance; bikini/lingerie body clearly visible (5), e.g., photo clearly depicts girl/woman in a bikini/lingerie, and nude (6).

Touch (κ = .88–.89) was coded as no touching (0), e.g., not touching another person; non-sexual touching (1), e.g., head is touching another person’s head in a non-sexual way; somewhat sexual touching (2), e.g., hugging a male peer; clearly sexual touching (3), e.g., kissing a male or female peer on the mouth.

Mouth (κ = .81) was coded as not suggestive of sexual activity (0), e.g., smiling; somewhat suggestive of sex (1), e.g., “duck face;” and explicitly suggestive of sex (2), e.g., licking a lollipop in a sexualized way.

Finally, a composite score, called sexualization total, was created that summed the scores of the five sexualized characteristics.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Participants reported logging on to Facebook most days of the week (M = 5.61, SD = 1.87). During the week, they averaged almost an hour on Facebook per day (M = 51.74 min, SD = 56.75, range 1–360 min). During the weekend, they averaged slightly more time on Facebook (M = 59.28 min, SD = 61.95, range 0–300 min). Regular Facebook users spent more time on Facebook than less regular users. Participants who reported logging on to Facebook 6 or 7 days a week (n = 76) averaged 64.63 weekday minutes (SD = 62.77) and 73.00 weekend minutes (SD = 67.83) on Facebook compared to participants who reported logging on to Facebook five or fewer days a week (n = 36) who averaged 24.88 weekday minutes (SD = 26.32) and 30.69 weekend minutes (SD = 33.02) on Facebook.

Adolescent girls (M = 5.31 days, SD = 1.97) did not differ from young adult women (M = 5.93 days, SD = 1.70) in the frequency of logging onto Facebook, t(110) = −1.76, p = .081. Similarly, they did not differ on the number of minutes spent on Facebook, weekday t(109) = −.75, p = .456 and weekend t(109) = .03, p = .979.

Profile Photos

Content

The number of profile photos ranged from 1 to 363 (M = 43.99, SD = 44.35). Young adult women (M = 53.41, SD = 57.06) had more profile photos than adolescent girls (M = 34.42, SD = 27.19), t(68.99) = −2.18, p = .033. After removing a young woman with 363 profile photos as an outlier, the group difference remained, but the average number of profile photos for young women dropped to 47.22 (SD = 36.43).

A total of 1189 photos were analyzed for the content of their profile photos. There were no age differences in the content of photos adolescent girls posted compared to young adult women, t(1101) = −.23, p = .817. The most common type of photo was of the participant, either a “selfie” or a photo taken by someone else depicting just the individual (34 %). The second most frequent type of photo was a group photo which captured people rather than action (24 %). No other type of photo (e.g., pets, family, nature) exceeded 5 % of the sample including non-objectified portrayals of the self, such as photos depicting the participant actively engaged in a physical activity (2 %), photos depicting the participant in a hobby (1 %), or photos depicting the participant in graduation regalia (less than 1 %).

Only photos that depicted the participant were coded for sexualization cues (n = 919). Photos that depicted pets, landscape, other people, etc. were dropped from this analysis. Overall, sexualization cues in profile photos were low (see Table 1). However, there were select photos that were fairly sexualized, e.g., a 17-year-old late teen had a profile photo featuring four teen girls in lingerie that accentuated their cleavage with bunny/cat ears on Halloween. Age differences were found for two sexualization cues, pose and touch (see Table 1).

Interview Questions

Motives for Sexualization

In response to the question “why do teen girls/young women use swimsuit or underwear pictures as their profile photo?,” girls and women reported at a high rate that those photos were for attention/exposure (78 %; κ = .88). For example, a 25-year-old young woman reported, “I think they do it to show off their body either because they’re fairly proud or because they are trying to get a boyfriend with their body.” A 17-year-old late teen expressed, “Because they look skinny and they want guys to notice them.” A 15-year-old early teen reported, “I think they do that probably for guys to comment on it, or their friends or something, to get attention, or maybe to feel sexy. Maybe they are really comfortable with their body, but they kind of put it out there for everyone to see…” There were no age differences in the likelihood of making an attention/exposure statement, χ2 (2, n = 168) = 1.93, p = .415.

The only other type of rationale present in at least 10 participants’ responses was the negative self-image theme (6 %; κ = .81). For example, a 20-year-old young woman reported, “If I saw a girl with that, I would think she was very like insecure, ‘cause the only reason to have that as your profile picture is to like get a lot of attention for it.” The Fisher’s exact test was used to investigate potential age differences in the prevalence of self-image statements. There were no age differences (p = .252).

Acceptability of Photos

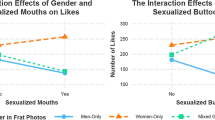

Figure 1 represents participants’ attitudes about the acceptability of posting swimsuit or underwear photos (clear approval, conditional dis/approval, reluctant disapproval, clear disapproval). Below are example statements by attitude. Fisher’s exact tests were conducted to investigate potential age group differences in the prevalence of particular attitudes because it is more suitable than the Chi-Square test when sample sizes are small or data are unequally distributed as is the case with the present data. The convention is to report the p value for a Fisher’s exact test. Table 2 provides the frequencies of rationales for attitudes toward each type of photo. Below are example statements of rationales. When rationales repeat across types of photos, only novel rationales are described for brevity.

Swimsuit Self Acceptability

In response to the question “do you think it’s OK to post a profile photo of yourself in a swimsuit?,” the most common response was conditional approval/disapproval (41 %). Responses in this category differentiated conditions under which it is OK and conditions under which it is not OK to post such a photo. One distinction was between being at a water-based location (approval) versus posed (disapproval) (n = 29), e.g., a 15-year-old early teen reported, “Like if I was trying to look all sexy and stuff, I think that would be disrespectful for yourself. But if it was just like playing around, like taking a picture, like running through sprinklers or like hanging out with friends or something, that would be fine.” A second distinction was made between a skimpy (disapproval) versus not revealing swimsuit (approval) (n = 5), e.g., a 15-year-old early teen reported,” Honestly, if it’s a bikini, no. I have tankinis. I’ll wear that and I can wear that. I can, I can put some on, just if it doesn’t reveal anything.” Clear disapproval was also expressed at a high rate (38 %), e.g., a 20-year-old young woman reported, “No, because I’m not that kind of girl. I’m not a slut.”

In contrast, approval (e.g., 23-year-old young woman, “I don’t see anything bad with, you know, wearing a swimsuit. It’s not like you’re completely naked. I mean you go to the beach and you’re wearing a swimsuit. So I guess that a lot of people are going to see you. I don’t see anything bad with it at all”) was expressed at a lower rate. Similarly, reluctant disapproval (e.g., 15-year-old early teen, “I think it has to do with yourself, if you feel comfortable with it you can, but I personally wouldn’t. I don’t think I would feel comfortable”) was expressed at a lower rate.

Age was related to the likelihood of endorsing particular attitudes toward posting a swimsuit photo of themselves (p = .005). Early (53.7 %) and late teen (52.8 %) girls were more likely to report conditional approval/disapproval than were young women (14.3 %). Instead, young women (54.3 %) were more likely than early (34.1 %) and late (27.8 %) teens to issue a clear disapproval.

Swimsuit Self Rationale

In providing a rationale for why they would/would not post a swimsuit photo, participants most commonly reported privacy concerns (κ = .82). For example, a 17-year-old late teen reported, “I wouldn’t. I just don’t think that needs to be on the internet. And I don’t feel comfortable sharing that. Because it goes, I mean the internet can go anywhere. So I wouldn’t post a picture like that.” There were no age group differences (early teens: M = .34, SD = .48; late teens: M = .19, SD = .40; young women: M = .23, SD = .43) in the prevalence of the privacy rationale, F(2,111) = 1.20, p = .307.

The second most common rationale was that those photos are inappropriate (κ = .73). For example, a 16-year-old early teen reported, “I don’t like showing off my body, so I think putting a picture of me in a swimsuit on Facebook is just too inappropriate for me; it just is”. There were age group differences in the prevalence of the inappropriate rationale, F(2,111) = 4.14, p = .018, partial η2 = .07. Early teen girls (M = .32, SD = .47) were more likely than young women (M = .06, SD = .24) to report that swimsuit photos were inappropriate. Late teens (M = .22, SD = .42) did not differ from early teens or young women.

Body image concern was the third most frequent rationale (κ = .91). For example, a 22-year-old young woman reported, “I’m not confident or comfortable with my current weight… I’m not confident in my own physical appearance to be flaunting that much of me.” There were age group differences in the prevalence of the body image concerns rationale, F(2,143) = 5.71, p = .004, partial η2 = .08. Young women (M = .20, SD = .41) were more likely than early teen girls (M = .02, SD = .13) to report body image concerns as a reason for not posting a swimsuit photo. Late teens (M = .07, SD = .25) did not differ from early teens or young women.

Relationship concern was the last theme that met the 10 participant threshold (κ = 1.00). A 17-year-old late teen reported, “I know my parents and relatives wouldn’t really approve of that.” There were no age group differences (early teens: M = .04, SD = .19; late teens: M = .07, SD = .25; young women: M = .11, SD = .32) in the prevalence of the relationship concern rationale, F(2,143) = 1.13, p = .327.

Swimsuit Other Acceptability

In response to the question “what is your opinion of another girl/young woman who would post a profile photo of herself in a swimsuit?,” the pattern of responses was similar to the swimsuit question about the self with conditional approval/disapproval (40 %) as the most common response and the water-based location versus posed as the most frequent distinction (n = 16) (see Fig. 1). In contrast to the swimsuit question about the self, clear disapproval was expressed at a lower rate (21 %) and approval (19 %) was expressed at a somewhat higher rate for this swimsuit question about another girl/woman.

Age was related to the likelihood of endorsing particular attitudes toward other girls or women posting a swimsuit photo (p = .018). Young women (40.0 %) were more likely to report that swimsuit photos are OK for other girls/women than were early (11.4 %) and late teen (15.2 %) girls. Early teens (40.0 %) were more likely to report clear disapproval than were late teens (21.2 %) and young women (10 %).

Swimsuit Other Rationale

In describing their opinions about other girls/young women posting swimsuit photos, participants most commonly issued a character indictment (κ = .85) (see Table 2). For example, a 15-year-old early teen reported, “My opinion is that they would be kind of slutty in all honesty.” There were no age group differences in the prevalence of these statements (p = .46) (early teens: M = .22, SD = .42; late teens: M = .22, SD = .42; young women: M = .14, SD = .40). Also common were explanations that these girls/women are seeking sexual attention (κ = .72; e.g., a 22-year-old young woman reported, “Some people just don’t get enough attention as is on the social, online network. They just look for it in other places. They just want to look sexy and they want someone to say something about it”). There were no age group differences in the prevalence of these statements (p = .69) (early teens: M = .17, SD = .38; late teens: M = .25, SD = .44; young women: M = .20, SD = .41). Seeking attention in general explanations occurred at the same rate as seeking sexual attention statements (κ = .84; e.g., a 16-year-old early teen reported, “she is just trying to get attention”). There were no age group differences in the prevalence of these statements (p = .68) (early teens: M = .15, SD = .36; late teens: M = .22, SD = .42; young women: M = .20, SD = .41). Finally, body image confidence was the last theme that met the ten participant threshold (κ = .78; a 16-year-old early teen reported, “I would think that they must be confident because, you know, they’re okay with their body image to put that on there.”). There were no age group differences in the prevalence of these statements (p = .37) (early teens: M = .06, SD = .24; late teens: M = .08, SD = .28; young women: M = .14, SD = .35).

Underwear Self Acceptability

In response to the question “do you think it’s OK to post a profile photo of yourself in underwear?,” the most common response by far was clear disapproval (91 %). For example, a 17-year-old late teen reported, “Definitely not because that’s something that’s meant to be shown to other people under very limited circumstances. So I just think that’s going a little too far and a little too out of the boundaries of what a teen-aged girl should be exposing herself to.” No participant expressed approval and very few expressed reluctant disapproval or conditional approval/disapproval. There were no age differences in the prevalence of particular attitudes (p = .232).

Underwear Self Rationale

In providing a rationale for why they would/would not post an underwear photo, similar to the swimsuit question about the self, participants most commonly reported privacy concerns (κ = .69). There were no age group differences in the prevalence of these statements (p = .31) (early teens: M = .59, SD = .50; late teens: M = .67, SD = .48; young women: M = .49, SD = .51). The second most common rationale was that those photos are inappropriate (κ = .73). There were no age group differences in the prevalence of these statements (p = .30) (early teens: M = .44, SD = .50; late teens: M = .28, SD = .45; young women: M = .31, SD = .47).

Four other themes occurred above the 10 participant threshold but in less than 10 % of responses including relationship concerns (κ = .96) (no age difference, p = .09), seeking sexual attention (κ = .95) (no age difference, p = .99), character indictment (κ = 1.00) (no age difference, p = .98), and respect (κ = .95) (no age difference, p = .88). Only the respect theme was not described in responses to the swimsuit questions. A 16-year-old early teen reported, “I don’t think it’s okay because you’re like not showing respect about yourself and you’re just kinda like letting everyone see what you are.”

Underwear Other Acceptability

In response to the question “what is your opinion of another girl/young woman who would post a profile photo of herself in underwear?,” the pattern of responses was similar to the underwear question about the self with clear disapproval (70 %) as the most common response. For example, a 14-year-old early teen reported, “I would think she’s really slutty. And also think she’s just trying to get attention. [Interviewer: And who do you think she’s trying to get attention from?] Boys.” In contrast to the question about the self, participants expressed reluctant disapproval (19 %) at a higher rate. For example, a 24-year-old young woman reported, “I don’t think I would think she was a slut or anything. It’s just the society that we live in that it’s appropriate to post things like that are encouraged, so it’s not necessarily her fault. I blame society! I don’t know; I wouldn’t do it but that’s okay if other people do it. Yeah, I don’t think I would pass judgment. I have friends that have swimsuit and scandalous pictures up and whatever and it’s their prerogative; it’s up to them.” Approval and conditional approval/disapproval were expressed at low rates.

Age was related to the likelihood of endorsing particular attitudes toward other girls or women posting an underwear photo (p = .001). Early (89.7 %) and late (80.0 %) teens were more likely to report clear disapproval than were young women (46.9 %). Young women (34.4 %) were more likely to express reluctant disapproval than were early (10.3 %) and late (17.1 %) teen girls.

Underwear Other Rationale

In describing their opinions about other girls/women posting underwear photos, participants most commonly issued a character indictment (κ = .83). There were no age group differences in the prevalence of these statements (p = .07) (early teens: M = .39, SD = .49; late teens: M = .53, SD = .51; young women: M = .26, SD = .44). Second most common were statements that girls/women with underwear photos are seeking sexual attention (κ = .71). There were no age group differences in the prevalence of these statements (p = .41) (early teens: M = .27, SD = .45; late teens: M = .39, SD = .49; young women: M = .40, SD = .50). The privacy concerns (κ = .88) theme was the third most common. There were no age group differences in the prevalence of these statements (p = .41) (early teens: M = .14, SD = .35; late teens: M = .07, SD = .25; young women: M = .13, SD = .34).

Three other themes occurred above the 10 participant threshold but in 10 % or less of responses including, inappropriate (κ = .88) (no age differences, p = .19), respect (κ = .96) (no age difference, p = .14), and seeking general attention (κ = .80) (no age difference, p = .68).

Long-Term Implications and Feminist/Structural Analysis

Only 7 % of participants described any long-term implications of posting a sexualized profile photo, e.g., a 19-year-old late teen reported, “I don’t know what I’m going to do with the rest of my life and the last thing I want to do, like I said, is be a politician and oh, look at her when she was eighteen. She posted pictures of herself nearly naked. You know, we can’t trust her.” Statements in this category were offered by late teens (n = 4), young women (n = 3) and an early teen (n = 1). Just two responses from 17-year-olds mentioned concern about how a sexualized photo might affect college admissions.

Only 7 % of participants offered a structural or feminist rationale for why a girl or woman would post a swimsuit/underwear photo, e.g., a 19-year-old late teen reported, “I guess it’s just going back to the way society views everything today. Basically what it tells you is you have to look that way. You have to look sexy or be attractive. You can’t be overweight. You have to have a perfect stomach. You have to have perfect skin. And it also tells [you that] guys like less clothes. They like you to look that way. They want to see you that way. Especially with media, movies, everything tells you that. So that’s how they want to portray themselves. That they can be attractive.” Statements in this category were offered by young women (n = 5) and late teens (n = 3).

Discussion

Prior research has documented the widespread sexualization of girls and women in both traditional and new media (e.g., APA 2007; Papadopoulos 2010; Manago 2013; Ringrose 2011; Ringrose et al. 2013; Rush and La Nauze 2006; Ward 2016). Arguably girls today are socialized into sexiness through the media and consumer culture (Levin and Kilbourne 2008; Murnen and Smolak 2013; Shewmaker 2015). Even as sexiness is rewarded, however, it is also penalized (e.g., Baumgartner et al. 2015; Daniels and Zurbriggen 2016; Manago et al. 2008; Murnen and Smolak 2013). Findings from the present study reflect a penalty in the form of negative peer attitudes that a sexualized self-presentation on social media might elicit. Participants overwhelmingly disapproved (either in a reluctant or a clear manner) of posting a profile photo of oneself in underwear on social media. This is consistent with findings from a study with German teens in which just 5 % of participants reported they were likely or very likely to post a photo in underwear or swimwear on social media (Baumgartner et al. 2015). A somewhat different pattern emerged in attitudes about posting a profile photo of oneself in a swimsuit in which specific conditions were laid out determining whether swimsuit photos were acceptable or not. However, swimsuit photos depicting an individual posed in a sexy manner or in a revealing swimsuit were not considered acceptable. In addition, character indictment (e.g., “I would think she was slutty”) was the most common theme in rationales of why it is not acceptable for another girl/women to post a swimsuit or underwear photo. Further, participants displayed few sexualization cues on their own Facebook profiles, suggesting that their behavior is consistent with their negative attitudes toward sexualization on social media.

As participants expressed their disapproval, the terms “slut,” “slutty,” and “skank” were commonly used and were coded as character indictments. In some cases, condemnation was particularly vehement, e.g., “that they’re skanks and they are sluts and probably whores” (20-year-old, young woman). Some participants explicitly reported that they would not want to be associated with a peer who posted a sexualized photo because this behavior is not respectful to oneself, e.g., “That she’s really gross, and not very classy, or smart, or respectful. Yeah, not someone who I would want to be friends with” (14-year-old, early teen). These attitudes reflect traditional beliefs about female sexuality that classify women as either the Madonna, pure and virginal, or the whore, promiscuous and dirty (Crawford and Popp 2003; Valenti 2010). This dichotomy pits “good” girls, who reserve sex for long-term, committed relationships, against “bad” girls, who have casual sex outside the bounds of a committed relationship (Armstrong et al. 2014). For example, a 17-year-old, late teen reported, “like no matter what kind of picture it was, they’d be in their underwear and showing off too much which means they don’t care if the whole world sees that which means they probably had a lot of people already see that. And so they’d probably be the ones like sleeping around and dating and that kind of bad stuff.” This participant’s response clearly reflects the belief that girls/women should not have sex outside of a committed relationship (“sleeping around”) because it is “bad.”

Traditional attitudes about sexuality also pit women’s sexuality against men’s. Whereas women, at least “good” ones, are supposed to only have sex in committed relationships, men are expected to desire and engage in sex any time regardless of emotional or relationship concerns (Crawford and Popp 2003; Valenti 2010). These beliefs, known as the sexual double standard, are the foundation for the practice of slut shaming which involves derogating women for presumed sexual activity (Armstrong et al. 2014). In the present study, slut shaming was common as can be seen in the discourse about being a slut either in the form of the participant’s own beliefs or commentary about how other girls/women would perceive sexualized photos. For example, a 19-year-old, late teen reported, “if somebody asked to be my friend that I didn’t know… and they were wearing underwear I’d be, “Oh, gosh, I really don’t like her. She’s a skank. (Interviewer asks for elaboration on ‘skank.’) Skank would be like someone who would be sexually promiscuous.”

It is not terribly surprising to see the Madonna/whore dichotomy, the sexual double standard, and slut shaming reflected in participants’ beliefs given how entrenched these ideas are in U.S. society. Valenti (2010) outlined the importance of female purity in contemporary U.S. culture which links a girl’s/young woman’s value as a person to her status as sexually inexperienced. Valenti traced the origin of this phenomenon historically to when women were considered property rather than as autonomous beings and men could ensure paternity by marrying a virgin. Women who had sex outside of marriage were considered “damaged goods” because their marketability as a wife was diminished. In the present day, women are largely no longer considered property in the U.S., however, instead a woman’s morality has become tightly tied to her sexual status. “Moral” or “good” girls do not have sex. This is the cultural heritage that girls and young women in the present study have inherited. Accordingly, it is reasonable that they apply these beliefs to their own behavior (e.g., few sexualization cues in their profile photos and denial that they would post sexualized photos themselves) and they police other girls’/women’s behavior (disapproval of other girls/women posting sexualized photos). Here we see gender stereotypes long apparent in the offline world, including the tendency to treat women as sexual objects, being applied to the online environment.

Indeed, adolescent girls and young women are at constant risk for slut shaming for presumed or actual sexual activity despite more permissive social norms around sexual activity outside of marriage today (Tanenbaum 2000, 2015). Furthermore, fear of this label impacts a range of women’s choices and behaviors. In an interview study of women in their 20–60s, Montemurro and Gillen (2013) found that women are concerned about and routinely monitor their dress for sexual messages others might infer. They also judge other women’s dress for appropriateness and make moral judgments based on dress. Women who wear sexier clothing are perceived as being less moral and risk being labeled a “slut” based on their clothing choice. Participants in this study typically blamed women in sexy clothing for making women as a group look bad or encouraging predatory sexual behavior from men. Few offered critiques of the cultural practice of stigmatizing sexy women. In a study of college women, Hamilton and Armstrong (2009) found slut stigma constrains women’s sexual behavior, e.g., choosing not to “make out” with “too many” men for fear of being labeled a slut. Thus, the specter of being labeled a slut impacts women’s day-to-day lives in terms of such a basic activity as deciding what to wear as well as decisions about socially appropriate ways to manage sexual desire. The present findings suggest that social media behavior is also impacted by this concern.

Teens may learn about social judgments tied to their sexuality in institutions they participate in daily. Sexual education programs offered in many U.S. schools often stress the connection between moral standing and sexual behavior, e.g., responsible young people wait until marriage for sex (Santelli et al. 2006). In 1996, Congress enacted a $50 million annual program to fund abstinence-only sexual education in schools (Haskins and Bevan 1997). Between 1996 and 2011, Congress allocated $1.5 billion to these programs (Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States n.d.), meaning that millions of U.S. children receive abstinence-only sexual education in school and community settings. A congressional review of the content of the most popular curricula used in these programs found that the majority contained errors and distortions of public health information including stereotyped beliefs about gender that characterize women as weak and in need of male protection and men as sexually aggressive and indiscriminate (United States House of Representatives 2004). Thus, young people in the U.S. routinely receive information that links morality to sexual behavior and reinforces gender stereotyped ideas about sexuality through sexual education programs. Exposure to these messages may be reflected in participants’ attitudes in the present study.

Participants’ rationales of their attitudes focused on a fairly narrow set of topics, primarily moral character, inappropriateness, seeking attention, and privacy concerns. Very few participants made statements that reflected a structural or feminist analysis of why individuals might post sexualized photos, e.g., cultural pressure on girls to be sexy. Similarly very few participants made statements about possible long-term implications of posting a sexualized photo on social media, e.g., these photos might be judged negatively by employers and/or college admissions committees. For the teen participants, especially early teens, this may be reflective of their level of cognitive development. The development of abstract and critical thinking skills, which would be involved in critiquing societal systems and thinking about the future, occurs in later adolescence and young adulthood (Fischer and Pruyne 2003; Keating 2004). These cognitive limitations may also hinder teens’ ability to fully connect their own behavior to the social media landscape. For example, the 17-year-old late teen who posted a profile picture of her and her friends in sexy Halloween costumes reported that a photo of her in underwear would be “highly inappropriate.” She also went on to say, “I just don’t think that that needs to be out on the internet. Anyone can see that and it’s there forever.” It is puzzling that the participant’s actual behavior directly contradicted the attitude she expressed toward overt sexualization on social media. Perhaps, in her eyes, the social nature of her photo in the context of celebrating Halloween overrode the sexualization apparent to the viewer. It may take specific educational efforts by parents and teachers to help young people fully connect their behavior to audience perceptions on social media.

We also observed that no participants described how posting sexualized photos might be empowering for girls/women which is in contrast to the scholarly proposal (described in the “Introduction” section) suggesting that engaging in self-sexualizing behavior is subjectively powerful (Peterson 2010). When examining our data, we observed a total absence of commentary about how posting a sexualized profile photo could be an act of empowerment. Instead, participants routinely discussed how girls/women who posted those photos were seeking sexualized attention from boys/men and this behavior was typically viewed negatively. However, future research that interviews girls and women who post sexualized photos of themselves might uncover themes of empowerment that were not seen in our sample of girls/women.

In their discussions of why swimsuit/underwear photos are/are not acceptable, participants tended to objectify other girls/women. The language of slut shaming denies the target her personhood and reduces her to her sexuality. Interestingly, the most common type of profile was of the participant herself. Photos of her engaged in a physical activity or a hobby or in graduation regalia were infrequent. Thus, photos that present merely one’s physical appearance were far more common among girls/young women than photos that feature one’s personhood. Arguably, this is a form of self-objectification in which physical appearance is prioritized over physical competence, personal interest, and academic achievement. The popularity of ‘self’ photos likely reflects the cultural pressure girls/young women feel to be sexually attractive. Their negative attitudes toward sexualized photos, however, seem to reflect the delicate line between acceptable/unacceptable ways to display one’s body that girls/women must negotiate. The limited number of sexualization cues observed in their Facebook profile suggests that our participants are aware of negative social attitudes toward self-sexualizing on social media and they conform to those standards of behavior.

Underwear Versus Swimsuit

Participants’ attitudes about underwear photos were clearly negative. In contrast, attitudes toward posting a swimsuit photo were somewhat less clear. A sizable number of participants made statements that were classified as conditional approval/disapproval. The most popular distinction was between a swimsuit photo at a water-based location (e.g., a lake) which was acceptable and a swimsuit photo posed in a bathroom or bedroom trying to look sexy which was not acceptable. Thus, participants connected the context of the photo to a motive, e.g., capturing a good time with friends at the lake versus trying to attract male attention. The content of the photo itself, i.e., a girl/woman in a swimsuit, was less important than the context. As noted above, young people may need help in fully evaluating the impact of posting a particular photo on social media. Photos posted to social media may feel somewhat ephemeral given the large volume of content that flows through that medium on a daily basis. Nevertheless, any content including photos can be captured by audience members and used for purposes the author may not have intended. Thinking through these possibilities requires the use of cognitive skills that are not fully developed until the mid-20s (Fischer and Pruyne 2003; Keating 2004).

The findings demonstrate that overt self-sexualization is not acceptable to most girls/young women, but displaying your body in a limited way under certain conditions is acceptable. Navigating the boundaries of what is acceptable versus not acceptable is doubtlessly quite challenging. For example, girls may want to be like their friends and wear a bikini at a water-based social event, but must monitor whether their bodies are covered sufficiently to meet expectations of social acceptability within their peer context while knowing that photos of the event will likely be posted on social media. Opting out of being in photos could result in being labeled a prude, self-conscious about one’s body, or other negative attention. Thus, decisions about how one is portrayed on social media may be tightly tied to peer dynamics.

Indeed, the importance of the peer context was apparent in a less frequent distinction raised under the conditional approval/disapproval category. A few participants described how their attitudes toward the owner of a swimsuit/underwear photo depended on whether she was a friend or a stranger. For example, a 19-year-old late teen reported, “it would really depend on if I knew her or not because if she was one of my friends, then I will probably think it’s okay. But if I didn’t know her, or I knew her and I thought she was kind of slutty, then I probably wouldn’t think it is okay.” Therefore, the same behavior can be read differently depending on the peer context. In her research on slut-bashing, a more extreme version of slut shaming, among teen girls, Tanenbaum (2000, 2015) found the same pattern. Some girls are victimized for being sexually active (whether they are in fact sexually active or not), whereas others are not, depending on peer dynamics. In addition, Jewell and Brown (2013) found that perceptions of peer attitudes about the acceptability of sexualized behaviors (e.g., making sexual comments) was related to individuals’ actual perpetration of these behaviors among college students. If individuals believed their peers were okay with sexualized behaviors, they were more likely to engage in those behaviors themselves. Baumgartner et al. (2015) found a similar peer pattern among teens who post sexualized photos on their social media profiles; adolescents who had more friends who posted photos in swimwear or underwear on social media were themselves more likely to post such photos. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that girls and young women must navigate a difficult set of social rules that dictate how they should or should not demonstrate sexuality both in offline and social media contexts.

Age Differences

No age differences in attitudes were observed between early teens and late teens, suggesting teen girls have a shared understanding of the cultural meaning of girls posting sexualized photos on social media. In contrast, young women’s attitudes toward other young women’s behavior were more permissive than early or late teens’ attitudes toward their peers. Specifically, young women were less likely than teens to express clear disapproval of other young women posting a swimsuit or underwear photo. These patterns may be related to cognitive advancements that occur in late adolescence and the early 20s. Specifically, reflective judgment, the ability to critically evaluate evidence and arguments, begins to develop in a series of stages during this time period (Perry 1970/1999). Multiple thinking, the first stage, entails an appreciation of multiple perspectives on an issue, an understanding that each perspective may have merit, and reluctance to judge one position as more valid than another. Multiple thinking was evident in some of the young women’s responses. For example, a 23-year-old young woman reported, “I tend to be more of the opinion that like underwear should be like a private thing. But I don’t have any particularly strong objections. I guess I sort of don’t feel particularly strongly either way about it. I think it definitely gives like fairly strong messages about, like, what you are looking for and what you are interested in. But, you know, like, again, if someone wants to give off that impression about themselves and if that is an accurate impression, then good for them.” Unlike the teens in the present study, some young women may have engaged in multiple thinking when judging other young women’s behavior more permissively.

Limitations and Future Directions

A limitation of the present study was the lack of ethnic diversity in the sample. Attitudes toward the sexual behavior of members of particular ethnic groups are informed by ethnic group stereotypes (Reid and Bing 2000). Media play a role in the perpetuation of these stereotypes (Monk-Turner et al. 2010). Women in particular racial/ethnic groups, including African-Americans, Latinas, and Asian-Americans, have historically been and are presently subjected to media representation in which they are hypersexualized (Craig 2006; Mok 1998; Rivadeneyra 2011; Ward et al. 2013). Thus, girls of color must navigate sexuality development in adolescence against a backdrop of stereotypes about their sexuality. These stereotypes may impact how they portray themselves on social media and their attitudes toward the self-presentation choices of other girls/women of color on social media. Future research should include ethnically diverse samples to better understand these processes among girls/women of color.

Similarly, a focus on how social class shapes attitudes about sexualized self-presentations on social media should be considered in future studies. Armstrong et al. (2014) found that social status, which is tied to social class, is related to college women’s participation in slut shaming. They found that high status women used a discourse of ‘slutiness’ to demonstrate class privilege and distance themselves from low status women, whereas low status women used the same discourse to express class resentment against high status women. Future research should investigate if these class-based boundaries apply to attitudes toward girls’/women’s self-presentations in online spaces.

Another limitation of the present study is that we did not assess the sexual orientation of participants. It is possible that engagement in self-sexualization as well as attitudes toward sexualization on social media may be related to sexual orientation. Objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997) itself is premised on the male gaze, which may be less relevant to sexual minority girls and women. However, there may be different pressures around sexualization on sexual minority girls and women that should be investigated, as called for by the APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls (2007).

In future studies, attitudes toward boys’/young men’s sexualized behavior on social media should be examined. Cultural meanings assigned to male and female bodies are quite different (Bordo 1997, 1999). Physical strength has been valued in men in the U.S. back to the colonial era; however, the practice of objectifying male bodies in media only started in the 1980s (Luciano 2007). In contrast, attractiveness became a central priority in girls’ and young women’s lives in the twentieth century in the U.S. (Brumberg 1997). Further, girls and women are routinely depicted in sexually objectifying ways in media (APA 2007; Papadopoulos 2010; Rush and La Nauze 2006). Therefore, a man posing in swim trunks with no shirt may not be read by many as sexualized behavior, whereas a woman posing in a bikini likely is for at least a portion of viewers. Future research is necessary to better understand what constitutes sexualized behavior among boys/men as well as attitudes toward boys/men who self-sexualize in public spaces such as social media. It is likely that there are important differences. For example, in a case study, Manago (2013) found that a young man used particular frames, such as humor or rebelliousness, to accompany overt sexual displays on social media in an effort to distance himself from femininity and homosexuality.

Finally, future research could usefully include different methodologies than the present study. For example, a future study, using either an interview or experimental method, might use photographs with varying types of sexualization to better understand nuances in young people’s understanding of sexualization. For example, are there different attitudes toward varying levels of skin exposure, different types of swimsuits, or varying intentions of the photo? What are the defining lines between what is acceptable and what is not? These questions should be addressed in future research.

Implications/Conclusion

Taken together, our findings indicate that social media perpetuates gender stereotypes limiting female sexuality that exist offline. In addition, social media may be a fertile ground for slut shaming as we witnessed in the frequency of character indictment statements (e.g., “slut,” “slutty,” and “skank”). Our participants commonly incorporated slut shaming into their dialogue about what type of photo is acceptable/unacceptable to post online. Their explanations reflected traditional ideas about female sexuality and the sexual double standard, which limit female sexual behavior. These ideas are deeply steeped in U.S. culture (Valenti 2010) and are reinforced in popular abstinence-only curricula (United States House of Representatives 2004). We propose that comprehensive sexual education curricula with a clear emphasis on deconstructing gender stereotyped ideas about sexuality be used in schools and community settings to promote healthy sexuality among all youth. As feminist scholars have observed, adults and educators have long ignored adolescent girls’ sexual desires (see Tolman 2012 for a review). It is well past time to dispel cultural attitudes that condemn and restrict female sexuality as dirty and morally wrong. Furthermore, girls and young women should not have to routinely scrutinize their dress and (online and offline) behavior for fear of being labeled a slut.

Part of this effort should also focus on media literacy. Gill (2012) argued that there are limitations to what media literacy training can accomplish and noted that by focusing heavily on media literacy we are spending less attention demanding that the content of media—especially sexualized media—be changed. We agree with these points. However, we believe media literacy curricula that address social media specifically are important given the almost whole scale adoption of social media by young people and the electronic footprint using it entails. In our sample of active social media users, we observed a range of sophistication about social media from unsophisticated users who did not know what their privacy settings were to savvy users who articulated possible long-term consequences for posting a sexualized profile photo. In general across participants, we observed a lack of audience perspective-taking in their thoughts about social media use. Therefore, we believe there is a clear need for more education for young people, both female and male, about how to use social media in productive ways.

References

American Psychological Association, Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. (2007). Report of the APA task force on the sexualization of girls. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Retrieved from www.apa.org/pi/wpo/sexualization.html.

Armstrong, E. A., Hamilton, L. T., Armstrong, E. M., & Seeley, J. L. (2014). ‘Good girls’: Gender, social class, and slut discourse on campus. Social Psychology Quarterly, 77(2), 100–122. doi:10.1177/0190272514521220.

Aubrey, J. S., & Frisby, C. M. (2011). Sexual objectification in music videos: A content analysis comparing gender and genre. Mass Communication and Society, 14(4), 475–501. doi:10.1080/15205436.2010.513468.

Bailey, J., Steeves, V., Burkell, J., & Regan, P. (2013). Negotiating with gender stereotypes on social networking sites: From “bicycle face” to Facebook. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 37(2), 91–112. doi:10.1177/0196859912473777.

Baker, C. K., & Carreño, P. K. (2015). Understanding the role of technology in adolescent dating and dating violence. Journal of Child and Family Studies. doi:10.1007/s10826-015-0196-5.

Baumgartner, S. E., Sumter, S. R., Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2015). Sexual self-presentation on social network sites: Who does it and how is it perceived? Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 91–100. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.061.

Bay-Cheng, L. Y. (2012). Recovering empowerment: De-personalizing and re-politicizing adolescent female sexuality. Sex Roles, 66(11–12), 713–717. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-0070-x.

Bordo, S. (1997). Unbearable weight: Feminism, western culture, and the body. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Bordo, S. (1999). The male body: A new look at men in public and in private. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

boyd, D. (2014). It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brumberg, J. J. (1997). The body project: An intimate history of American girls. New York: Vintage Books.

Cikara, M., Eberhardt, J. L., & Fiske, S. T. (2011). From agents to objects: Sexist attitudes and neural responses to sexualized targets. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23, 540–551. doi:10.1162/jocn.2010.21497.

Collins, R. L. (2011). Content analysis of gender roles in media: Where are we now and where should we go? Sex Roles, 64, 290–298. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9929-5.

Craig, M. L. (2006). Race, beauty, and the tangled knot of a guilty pleasure. Feminist Theory, 7, 159–177. doi:10.1177/1464700106064414.

Crawford, M., & Popp, D. (2003). Sexual double standards: A review and methodological critique of two decades of research. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 13–26. doi:10.1080/00224490309552163.

Daniels, E. A. (2012). Sexy versus strong: What girls and women think of female athletes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 33, 79–90. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2011.12.002.

Daniels, E. A., & LaVoi, N. M. (2013). Athletics as solution and problem: Sports participation for girls and the sexualization of women athletes. In E. L. Zurbriggen & T.-A. Roberts (Eds.), The sexualization of girls and girlhood: Causes, consequences, and resistance (pp. 63–83). New York: Oxford University Press.

Daniels, E. A., & Wartena, H. (2011). Athlete or sex symbol: What boys and men think of media representations of female athletes. Sex Roles, 65, 566–579. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-9959-7.

Daniels, E. A., & Zurbriggen, E. L. (2016). The price of sexy: Viewers’ perceptions of a sexualized versus nonsexualized Facebook profile photograph. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 5, 2–14. doi:10.1037/ppm0000048.

Downs, E., & Smith, S. L. (2010). Keeping abreast of hypersexuality: A video game character content analysis. Sex Roles, 62, 721–733. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9637-1.

Fischer, K. W., & Pruyne, E. (2003). Reflective thinking in adulthood: Emergence, development, and variation. In J. Demick & C. Andreotti (Eds.), Handbook of adult development (pp. 169–198). New York: Kluwer.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Frisby, C. M., & Aubrey, J. S. (2012). Race and genre in the use of sexual objectification in female artists’ music videos. Howard Journal of Communications, 23(1), 66–87. doi:10.1080/10646175.2012.641880.

Gill, R. (2012). Media, empowerment and the ‘sexualization of culture’ debates. Sex Roles, 66, 736–745. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-0107-1.

Grabe, S., Hyde, J. S., & Lindberg, S. M. (2007). Body objectification and depression in adolescents: The role of gender, shame, and rumination. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 164–175. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00350.x.

Graff, K. A., Murnen, S. K., & Krause, A. K. (2013). Low-cut shirts and high-heeled shoes: Increased sexualization across time in magazine depictions of girls. Sex Roles, 69, 571–582. doi:10.1007/s11199-013-0321-0.

Graff, K., Murnen, S. K., & Smolak, L. (2012). Too sexualized to be taken seriously? Perceptions of a girl in childlike vs. sexualizing clothing. Sex Roles, 66, 764–775. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0145-3.

Gurung, R. A. R., & Chrouser, C. J. (2007). Predicting objectification: Do provocative clothing and observer characteristics matter? Sex Roles, 57, 91–99. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9219-z.

Hall, P. C., West, J. H., & McIntyre, E. (2012). Female self-sexualization in MySpace.com personal profile photographs. Sexuality and Culture, 16, 1–16. doi:10.1007/s12119-011-9095-0.

Hamilton, L., & Armstrong, E. A. (2009). Gendered sexuality in young adulthood: Double binds and flawed options. Gender & Society, 23, 589–616. doi:10.1177/0891243209345829.

Haskins, R., & Bevan, C. S. (1997). Abstinence education and welfare reform. Children and Youth Services Review, 19, 465–484.

Hatton, E., & Trautner, M. N. (2011). Equal opportunity objectification? The sexualization of men and women on the cover of Rolling Stone. Sexuality and Culture, 14, 256–278. doi:10.1007/s12119-011-9093-2.

Heflick, N. A., & Goldenberg, J. L. (2009). Objectifying Sarah Palin: Evidence that objectification causes women to be perceived as less competent and less fully human. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 598–601. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.008.

Jewell, J. A., & Brown, C. S. (2013). Sexting, catcalls, and butt slaps: How gender stereotypes and perceived group norms predict sexualized behavior. Sex Roles, 69, 594–604. doi:10.1007/s11199-013-0320-1.