Abstract

The current study examines men’s and women’s perceptions of both men’s and women’s use of token resistance in heterosexual relationships. Three hundred and forty (n = 340) individuals (148 men and 191 women) with an average age of 21.31 years (SD = 4.11) served as participants in an online study at a large, southwestern university. Results indicate that men perceive both men and women as using token resistance more than women do. Specifically, when examining a traditional sexual script in which the man is the sexually proactive partner and the woman is perceived as exercising token resistance, men believe that women engage in token resistance more than women do. In the scenario in which the woman is the sexually proactive partner and the man is the token resistant party, men perceive men using token resistance more than women do. Within gender, men perceive men using token resistance more than women do. Findings are discussed within the context of sexual script theory and the traditional sexual script.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Perceptions and interpretations regarding sexual attitudes and behavior are not necessarily clear cut; often, they entail shades of gray—misperceptions, miscommunication and misunderstanding. Perceptions might vary, among other things, regarding interpretations of want versus consent and/or how they are communicated. One such area in the literature involves the consideration of token resistance or scripted refusal (see Muehlenhard 2011, for more on the terminology) to refer to the notion of saying “no” to sex when an individual really means “yes.” Whereas some individuals might perceive token resistance as ambiguous or manipulative sexual game playing (e.g., Sprecher et al. 1994), others might perceive the ambiguity as genuine lack of assuredness during a sexual or potentially sexual encounter (e.g., Shotland and Hunter 1995). In a 2011 piece, Muehlenhard reflects on the literature in this area and suggests some considerations when studying this phenomenon, including, “We should avoid assuming that some topics are relevant only to women or only to men” (p. 681). Noted is that both men and women engage in token resistance in both heterosexual and homosexual relationships (e.g., Krahé et al. 2000). Sprecher et al. (1994), for example, acknowledge the stereotype of predominant female use of token resistance and examined men’s and women’s use of token resistance as well as consent/nonconsent and sexual wantedness/unwantedness in three countries (United States, Russian and Japan). Results indicate that both men and women engage in token resistance across cultures, with the men in the United States engaging in a greater proportion of token resistance than women. The authors also found that women in the United States submit to unwanted sex more than women in Japan or Russia. Contrary to stereotype of predominant female token resistance usage, other research also indicates that men engage in token resistance more than women do (Muehlenhard and Rodgers 1998; O’Sullivan and Allgeier 1994). As aptly noted by Muehlenhard (2011), many theoretical approaches to studying the notion of saying “no” when meaning “yes” assume a traditional sexual script approach, which argues that men are the actors of and women are the reactors to sexual advances and activity (e.g., Byers 1996).

Although gender assumed sexual proactive/reactive behaviors might be predominant in our heterosexual cultural sexual script, they are not necessarily static. Indeed, and as perhaps illustrated in the aforementioned literature regarding men’s use of token resistance, it is possible for women to be sexually proactive and men, reactive. It is also possible, as indicated, for both genders to say “no” when they mean “yes,” to have various positions regarding want versus consent and to experience degrees of want and consent (Muehlenhard and Rodgers 1998; Peterson and Muehlenhard 2007). In sum, men’s and women’s viewpoints on saying “no” when meaning “yes” are possibly perceptively different, particularly when considering the traditional sexual script. To that end, the purpose of this investigation is to examine men’s and women’s perceptions of their engagement in saying “no” to sex when they mean “yes” both between and within gender. To begin, traditional and predominant sexual scripts, as related to the U.S. culture, are examined.

Sexual Scripts

Within the context of heterosexual, sexual relationships, men and women often adhere to sexual scripts as a means for direction in navigating the relationship. Sexual scripts offer guidance on acceptable (Metts and Spitzberg 1996), stereotypical (Abelson 1981) or social learning and social constructionist approaches (Simon and Gagnon 2003) to sexual behavior. Sexual scripts are particularly interesting when examining the notion of token resistance because the stereotype of women engaging in token resistance more than men (e.g., Sprecher et al. 1994) finds varied support in the research (e.g., Muehlenhard and Rodgers 1998, etc.).

Wiederman (2005) addresses how sexuality and sexual scripts vary in Western culture, beginning with how differently boys and girls are socialized about their bodies during childhood and how they develop into young adults conditioned to believe that sex serves varied purposes and holds various meanings. Specifically, Wiederman argues that men are conditioned to be more comfortable with their bodies than women and are more readily socialized to perceive sex for pleasure and release as compared to women. Women, on the other hand, are conditioned to attach relational meaning to sex relative to men. To further disentangle sexual scripts, the three levels (cultural, intraspychic, interpersonal) of sexual script theory (Simon and Gagnon 1984, 1987) are addressed below. Then, this manuscript addresses the traditional sexual script (Byers 1996). Finally, of consideration are the scripts as they apply to both men and women in the context of saying “no” when they mean “yes” to sex (e.g., Muehlenhard 2011; Muehlenhard and Hollabaugh 1988; Muehlenhard and Rodgers 1998).

Sexual Script Theory

Cultural Scripts

Cultural scripts are the most extensive of the three levels of sexual script. Combining social and cultural expectations for cultural and social propriety in terms of sexual behavior in relational contexts, cultural scripts are largely influenced by the media (e.g., Metts and Spitzberg 1996; Simon and Gagnon 1984, 1987). Reflective of social and cultural expectations, cultural scripts can provide men and women guidance regarding what behavior, sexual and otherwise, men and women are expected to engage in within relational or sexual situations. Particular to the United States’ culture, much of the extant research suggests the predominance of traditional relational and sexual expectations in relational contexts. (e.g., Byers 1996; Emmers-Sommer et al. 2010). That is, traditional, heterosexual relational and sexual scripts position the man as sexually proactive and the woman as sexually reactive (e.g., Wiederman 2005). These assumptions are reflected in a dating or relational heterosexual script in which the man often asks for the date, provides transportation for the date and pays for the date expenses. If sexual activity occurs during and/or after the date, the script suggests that it would be the man who initiates the contact toward the more reactive versus proactive woman. That said, however, men and women can vary in terms of their attitudes and behaviors and deviate from the predominant traditional sexual script. For example, Sprecher et al. (1994) found a greater proportion of men in the United States culture to engage in token resistance than women, which might not be stereotypically expected by a script that positions men as sexually proactive. This notion is further disentangled below.

Intrapsychic Scripts

Intrapsychic scripts, as compared to the predominant cultural script, are comprised of personal wants and desires contributing to one’s sexual arousal (Metts and Spitzberg 1996; Simon and Gagnon 1984, 1987). That is, an individual can consider cultural scripts and engage in personalization of the script (Hynie et al. 1998). Intrapsychic scripts can be reflective of the predominant sexual script or be divergent. At a personal level, a man’s or woman’s intrapsychic script could align with or deviate from the predominant cultural script. For example, a man might prefer to be more reactive to sexual activity. Conversely, a woman—deviating from the predominant, traditional, cultural, heterosexual script—could be more sexually proactive, initiating, etc. than the male partner. As noted, much of the heterosexual cultural script focuses on men’s sexual proactivity. Yet, some research suggests that men engage in token resistance more than women do (e.g., Muehlenhard and Rodgers 1998; O’Sullivan and Allgeier 1994; Sprecher et al. 1994). A man’s or a woman’s personal desires can combine with culturally scripted expectations and be enacted in the interpersonal script. Wiederman (2005) notes that when men’s and women’s intrapsychic scripts align, there is more complementarity and less uncertainty between them.

Interpersonal Scripts

An individual’s personal desires interplay with social and cultural expectations (Metts and Spitzberg 1996; Simon and Gagnon 1984, 1987) and are reflected in the interpersonal script. Men’s and women’s engagement in behavior that mirrors culturally scripted expectations is perceived as more acceptable than behavior that digresses from such expectations (Byers 1996; Emmers-Sommer et al. 2010). Typically, when a woman diverges from the culturally expected script, it is perceived more negatively than when a man does so (Mongeau and Carey 1996; Muehlenhard and Hollabaugh 1988; Muehlenhard et al. 1985). To further explore heterosexual, cultural relational and sexual expectations, the traditional sexual script is examined below.

Traditional Sexual Script

The traditional sexual script (TSS; Byers 1996) addresses traditional relational and sexual expectations for men and women. As noted earlier, the TSS contends that men are conditioned to be sexually proactive in heterosexual relationships (Byers; Wiederman 2005). From a TSS standpoint, men who initiate and engage in sexual activity are celebrated whereas women who engage in kind are typically admonished (Byers 1996; Emmers-Sommer 2002; Wiederman 2005). According to the TSS, women often enact a relational gatekeeper role, engaging in enough sexual activity to keep her partner interested without deviating from the script to the extent that her reputation is called into question (Byers; Emmers-Sommer; Wiederman). More specifically, Byers (1996) outlines six assumptions of the TSS: (1) men are perceived as “oversexed” and women are perceived as “undersexed” (p. 9); (2) men’s value and status are elevated with sexual activity engagement whereas women’s value and status are tarnished due to sexual engagement (p. 9); (3) men initiate sexual activity whereas women assume the recipient role (p. 9); (4) women are expected to demonstrate lack of interest in sex to preserve their reputations. “Even when they are interested in engaging in sexual activity, women are expected to offer at least initial token resistance to the man’s advances” (p. 10); (5) a woman’s worth is increased by being in a romantic relationship (p. 10); and, (6) women are expected to be emotional and attentive in relationships whereas their male partners are expected to be unemotional, detached and self-important (p. 10). The TSS, then, paints women as passive, nonsexual, relational gatekeepers and men as sexually assertive and unattached. Byers’ research on the TSS found mixed support. Specifically, the author found that whereas men did initiate sexual activity more than women did, they were also inclined to accept a refusal as a refusal. Results also appear to have established that the TSS applies more to casual relationships than established ones, where the author indicates “men’s and women’s roles in sexual interactions overlap considerably” (p. 23), noting that women can be the initiators of sexual activity and the men engage in the refusal.

Token Resistance

As noted earlier, Muehlenhard (2011) addresses the terminology regarding literature on token resistance and scripted refusal, referring to her 1991 piece with McCoy in which Muehlenhard reports that the editor requested that the term “scripted refusal” be used in lieu of “token resistance” (Muehlenhard 2011, p. 676). Muehlenhard (2011) noted the reasons behind the editor’s request, indicating in the Muehlenhard and McCoy (1991) piece that:

(a) token resistance sounds consciously manipulative, whereas scripted refusal reflects the correspondence of this behavior to traditional sexual scripts, and (b) resistance seems physical whereas refusal seems verbal, which is probably a more accurate description of this behavior. (p. 460)

Muehlenhard (2011) reported that while perhaps neither term adequately captures the phenomenon of saying “no” when one means “yes,” the author used the term “token resistance” in her piece because that is the predominant term in the literature.

A variety of studies exist that examine token resistance (e.g., Mills and Granoff 1992; Muehlenhard 2011; Muehlenhard and Hollabaugh 1988; Osman 2003). Traditionally, token resistance (i.e., saying “no” when meaning “yes”) is considered a female practice (e.g., Byers 1996). As noted by Wiederman (2005), woman are socialized to play hard to get—the more “scarce” they are, the more desirable they are (p. 498). Aligned with sexual scripts and the TSS, women are often socialized to say “no” when they mean “yes” to preserve their reputations (e.g., Byers 1996). Muehlenhard and Rodgers (1998) found that token resistance isn’t used exclusively in newer relationships (i.e., to preserve one’s reputation), but that it is also used in established relationships. Engagement in token resistance, however, as noted, might not exclusively be considered a female practice (e.g., Muehlenhard and Rodgers 1998; O’Sullivan and Allgeier 1994). Muehlenhard and Rodgers (1998) qualitatively examined token resistance and found a variety of reasons for its use as well as use by both genders in heterosexual contexts. The reported reasons for using token resistance include “moral concerns and discomfort about sex, adding interest to a relationship, wanting not to be taken for granted, testing a partner’s response, and power and control over the other person moral reasons, not wanting to be taken for granted, wanting to preserve the relationship or to gain power over the partner” (p. 453). Muehlenhard and Rodgers also noted that men’s and women’s responses to their qualitative questions about token resistance indicated that perhaps some men and women misunderstood the question.

As suggested by Muehlenhard (2011), it is important to not necessarily assume that token resistance is can apply to both genders (p. 681). The notion of token resistance is an interesting one in the sense of the focus. Specifically, is the focus of a token resistant message on the “no” or the “yes” part of the concept or both? On one hand, from a traditional sexual script approach, one might expect women to engage in token resistance more than men in the sense of focusing on the “no”—“no” to sex to protect one’s reputation, etc. On the other hand, from a traditional scripted approach, one might expect men to engage in token resistance with a focus on the “yes” portion of the context. That is, if men engage in token resistance, is it more aligned with the notion of “yes, the sex will happen” and the utterance or engagement is “no” is more likely due to control or power issues? If such is the case, then perhaps token resistance used in this fashion isn’t reactive, but covertly proactive. These questions are likely best teased out qualitatively in future research. To begin, however, the purpose of this investigation is to quantitatively explore men’s and women’s perceptions of both genders saying “no” when they mean “yes,” with modifications in the script/measure offered to the participants to ascertain if the genders, indeed, differ in their perceptions of token resistance usage. Thus, the following research questions are presented:

RQ1

Do men and women differ in their perceptions of women’s use of token resistance?

RQ2

Do men and women differ in their perceptions of men’s use of token resistance?

Finally, within gender mean differences of men’s versus women’s use of token resistance are compared:

RQ3

Do women’s perceptions of men’s versus women’s use of token resistance differ?

RQ4

Do men’s perceptions of men’s versus women’s use of token resistance differ?

Method

Procedures

The current investigation represents part of a larger study on sexual perceptions among adults. Participants are undergraduate university students from a large, southwestern university who participated in the unit’s research participant pool. Students were enrolled in introductory communication courses and represented a variety of majors and interests. The study received approval from the university’s institutional review board (IRB). Procedures involved students signing up for the survey online and receiving the survey link online. Completing the survey took approximately 20 min of the participants’ time and participants received completion credit for partaking in the survey. Participants were informed prior to participating that the survey involved questions about sexual perceptions, that participation was voluntary, responses would be kept as confidential as possible and that they may skip any questions that they preferred not to not answer.

Instrument

Token Resistance to Sex Scale

Participants completed the token resistance to sex scale (TRSS; Osman 1998) as well as a modified version of the scale. According to Osman, the instrument was created to “measure the predispositional belief that women use token resistance to sex” (p. 685). The instrument provides a 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree Likert type measure, with higher means indicating a greater agreement that token resistance to sex is being exercised. For the current investigation, items were presented such that male and female participants completed the measure in its original form (e.g., “Going home with a man at the end of a date is a woman’s way of communicating to him that she wants to have sex” (Osman 1998, p. 685) and also in a modified form (e.g., “Going home with a woman at the end of a date is a man’s way of communicating to her that he wants to have sex”) or, “Women usually say ‘no’ to sex when they really mean ‘yes’” and, “Men usually say ‘no’ to sex when they really mean ‘yes’” to gain perspective if male and female participants perceive men’s and women’s exercising of token resistance differently. The TRSS scale yielded a reliability of .86 (Cronbach’s α) in former research (Osman 1998) and rendered a .80 in the current investigation (Cronbach’s α) for the original form of the scale in which the woman is perceived as exercising token resistance and .84 (Cronbach’s α) for the modified version of the scale in which the man is perceived as engaging in token resistance.

Sample

Three hundred and forty (n = 340) individuals served as participants in the study of which 148 were men and 191 were women (one participant did not report his/her gender). The mean age of the sample is 21.31 years old (SD = 4.11), with an age range of 18–59 years of age (three participants did not report their age). Participants’ current relational status is as follows: 135 individuals reported that they are single (not seeing anyone); 51 reported that they are casually dating; 122 reported that they are seriously dating; seven (7) reported that they are engaged; 19 reported that they are married; two (2) reported that they are separated; two (2) reported that they are divorced; and, one (1) reported “other” and indicated “complicated/seriously dating”). Participants were asked to report their sexual orientation and 305 reported that they were “heterosexual;” four (4) reported “gay;” six (6) reported “lesbian;” 16 reported “bisexual;” and, eight (8) reported “other.” Participants who reported “other” were offered the opportunity to explain their status. Of those participants who chose to elaborate, three (3) reported “pansexual,” two (2) reported “asexual,” one (1) reported “demisexual,” and one (1) reported “straight.”

Results

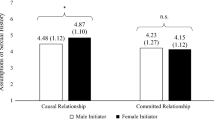

Research question one asked, “Do men and women differ in their perceptions of women’s use of token resistance?” Results indicate that in scenarios in which the man is the sexually proactive party and the women are perceived as the engagers in token resistance that men and women differ in perceptions. Specifically, men (M = 2.75, SD = 1.13) are more inclined to believe that women engage in token resistance than women are (M = 2.34, SD = .96) (higher mean = greater agreement), t (336) = 3.62, r = .19 (positive r indicates mean difference is in the predicted direction), p < .001.

Turning the tables, research question two asked if men and women differed in their perceptions of men’s use of token resistance in a heterosexual context. Specifically, research question two asked, “Do men and women differ in their perceptions of men’s use of token resistance?” Findings indicate that men (M = 3.50, SD = 1.41) are more inclined to agree that men engage in token resistance with a sexually proactive woman than women (M = 2.91, SD = 1.28) are inclined to agree that men engage in token resistance with a sexually proactive woman, t (334) = 3.98, r = .21, p < .0001 (Table 1).

Within gender, of interest is if women’s perceptions of women’s versus men’s use of token resistance differ. Research question three asked, “How do women’s perceptions of men’s versus women’s use of token resistance differ?” Comparing women’s scores on the perceived women’s (M = 2.34, SD = .96) versus men’s use (M = 2.91, SD = 1.28) of token resistance demonstrate a significant mean difference, t (376) = 4.87, r = −.24, p < .0001. Women report that they perceive men using token resistance more than women do.

Related, research question four asked, “How do men’s perceptions of men’s versus women’s use of token resistance differ?” Once again, in comparing men’s scores on perceived women’s use (M = 2.75, SD = 1.13) versus men’s use (M = 3.50, SD = 1.41) of token resistance indicate a significant mean difference, t (294) = 4.99, r = −.28, p < .0001. Men report that they perceive men using token resistance more than women do.

Discussion

The purpose of this investigation was to examine men’s and women’s perceptions of each gender’s engagement in saying “yes” to sex when s/he means “no.” Findings indicate that men and women differ in their perceptions of each gender’s usage of token resistance such that men perceive both women and men as engaging in token resistance more than women do. Also, within gender, both men and women are inclined to perceive men as engaging in token resistance significantly more than they perceive women as engaging in it. These findings are discussed below.

There are, perhaps, two things that move to the forefront in light of the findings and are discussed within the context of sexual script theories. First, men might perceive the token resistance practice as more of a game playing/foreplay exercise than women do; therefore, they perceive that men do it more than women do and both men and women perceive men as using it more than women do. It could be—and it is demonstrated in Muehlenhard’s work (e.g., Muehlenhard and Rodgers 1998)—that men and women are conceptualizing it differently, perhaps, at the onset and that men and women exercise token resistance differently and for different purposes—covertly to increase foreplay for men versus covertly to protect reputation for women. These possibilities can be further addressed in future research.

The notion of token resistance is demonstrated in the predominant literature as an individual saying “no” when meaning “yes.” Past literature, consistent with sexual script theory and the traditional sexual script, has focused on the predominance of women exercising token resistance as a means of protecting their reputation, not appearing overly eager to engage in sexual activity or as promiscuous (e.g., Byers 1996). Sprecher et al. (1994) acknowledge, “A popular stereotype is perpetuated in the media, film, and literature that women resist sex while desiring it” (p. 125) even though other research suggests that men use token resistance more than women (e.g., Muehlenhard and Rodgers 1998; O’Sullivan and Allgeier 1994; Sprecher et al. 1994).

Guerrero et al. (2013) point out that, problematically, when individuals engage in token resistance that the initiator of the sexual action is conditioned to believe that the “refusal” is insincere. In this study, men perceived that both men and women engaged in token resistance more than women did. Given the traditional sexual script—particularly when considering some of the extant work on gender differences and gendered usage of token resistance—one possible explanation or consideration in light of the findings is that men are focusing on the “yes” part of the token resistance context. That is—and potentially aligned with the TSS—it might be that men believe that when it comes to sexual opportunities and contexts, the assumption exists that men want to have sex and the “meaning yes” aspect of the token resistance practice is what is at the forefront of consideration. This would align with sexual script and traditional sexual script theories that men are more “oversexed” or sexually proactive than women. Within these saying “no” when meaning “yes” contexts, it is possible that women are more focused on the “no” aspect of the circumstances and, therefore, do not believe that women either use it as much as men or, possibly, that they really don’t want to have sex or are less likely to consent. Motley and Reeder (1995) emphasize the need for women to be emphatic when conveying sexual resistance, as they found men didn’t experience confusion about direct refusals, but didn’t necessarily interpret indirect refusals to sex as refusals. Muehlenhard and Rodgers (1998) noted that men and women might not understand or interpret token resistance in the same fashion as it has been examined in the literature. The current study is quantitative in nature and, therefore, the reasons are not teased out. Future research might want to further examine men’s and women’s perceptions and interpretations qualitatively, as Muehlenhard and Rodgers (1998) did nearly 20 years ago.

To continue, perhaps men and women both engage in token resistant behavior, but for different reasons. At the root of it is the notion that folks say “no” when they really mean “yes.” From a traditional sexual script standpoint, one might assume that men are more interested in having sex than women; thus, aligned with that, then, is the notion that if a man says “no,” one might be more likely to believe that he really does want to have sex whereas when a woman says “no,” one might be more inclined to believe that she really does mean no. Men might be perceived as less serious by a female partner than when a woman says no to a male partner. In an examination of sexual (un)want and (non) consent, Emmers-Sommer (2015) found that men’s unwant of sex with a female aggressor was not perceived as grievously as when a woman was the unwanting target of a male aggressor’s advances. Possibly, then, men and women perceive men saying “no” when they mean “yes” differently (i.e., less seriously) and, perhaps, for different reasons (i.e., for control reasons versus moral reasons or reputation reasons). Women, for example, might say “no” because of moral, pregnancy or reputation reasons whereas a man might say “no” to gain control of the female partner, to get her to have her “way” with him, etc., which might have been his plan all along (Muehlenhard and Rodgers 1998). Specifically, Muehlenhard and Rodgers report a male participant’s account of his use of token resistance for power reasons with a woman he met at a bar:

Now all I had to do was pretend like I didn’t want to for some kin or any kind of stupid reason to fit the situation. I always thought that would get a girl more anxious and ready for me. It’s worked most of the time. When I’m fucking them I then let them feel the wrath of what I wanted from the beginning (p. 456; cited in Muehlenhard 2011, p. 680).

What this aforementioned passage suggests is that, for some men, the use of token resistance is not intended for resistance purposes at all, but as an enhancement to foreplay. In this sense, what is suggested is that men’s intraspychic scripted desire is for the woman to be sexually aggressive and his engagement in token resistance will unleash that type of female behavior. With women, however, what the literature has suggested is that women engage in token resistance to protect their reputation and that the male pursuer be more aggressive to get her to finally acquiesce or succumb. Additional research can address strategies and intentions in using token resistance and if the focus is on the “no” or “yes” part of the message.

Future research might also want to consider continuing the address of token resistance in same sex relationships. As found by Krahé et al. (2000), as an example, token resistance is also exercised in same sex relationships. Focused on sexually ambiguous intentions and sexually aggressive acts, the authors found that being ambiguous about sexual intentions contributed to both perpetration and victimization and this held in heterosexual as well as homosexual relationships. Similar to Motley and Reeder (1995), these findings also indicate that a “no” must clearly be indicated as a “no.” What is interesting, however, and as aforementioned, is that some individuals appear to strategically be ambiguous as doing so might heighten sexual arousal and activity (e.g., Muehlenhard and Rodgers 1998). Past research has considered whether token resistance is used coyly or manipulatively (e.g., Sprecher et al. 1994) or because an individual really does feel unsure during a place in time during a sexual episode, but that ambiguity can evolve to a more assured affirmative response (Shotland and Hunter 1995).

Limitations

As with all studies, this investigation is not without some limitations. First, the data for this investigation were collected from undergraduate college students and, even though the age range was vast and myriad majors were represented in the sample, the mean age was nevertheless young. Future research might want to consider examining the use of token resistance across the lifespan. Second, this investigation did not examine reasons or intentions for the token resistant behavior; rather, the study is positioned as a starting point to explore how men and women perceive both genders’ use of token resistance both within and between gender. Future research might want to address token resistant intentionality across various sexual identities and relational contexts. Finally, although significant differences are found between and within gender regarding perceptions of token resistance, one must consider the findings in context. While it is the case that men report greater agreement with the token resistance measure than did women, the means are nevertheless modest and still placed nearer to the “strongly disagree” anchor than the “strongly agree” anchor. Thus, one might interpret the findings such that men disagree less with the token resistance measure items than do women or women disagree more with the item measures than do men.

Conclusion

The current study addresses both men’s and women’s perceptions of both men’s and women’s use of token resistance in heterosexual relationships. Men perceive that both men and women use token resistance more than women do. Specifically, when examining a traditional sexual script in which the man is the sexually proactive partner and the woman is perceived as exercising token resistance, men believe that women engage in token resistance more than women do. In the scenario in which the woman is the sexually proactive partner and the man is the token resistant party, men perceive men using token resistance more than women do. Within gender, men perceive men using token resistance more than women do. Additional research is suggested to further explore men’s and women’s strategies, reasons and meanings in contexts of saying “no” when meaning “yes.”

References

Abelson, R. P. (1981). Psychological status of the script concept. American Psychologist, 36, 715–729.

Byers, E. S. (1996). How well does the traditional sexual script explain sexual coercion? Review of a program of research. In E. S. Byers & L. F. Sullivan (Eds.), Sexual coercion in dating relationships (pp. 7–26). New York, NY: Haworth Press.

Emmers-Sommer, T. M. (2002). Sexual coercion and resistance. In M. Allen, R. Preiss, B. M. Gayle, & N. Burrell (Eds.), Interpersonal communication: Advances in meta-analysis (pp. 315–343). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Emmers-Sommer, T. M. (2015). An examination of gender of aggressor and target (un)wanted sex and nonconsent on perceptions of sexual (un)wantedness, justifiability and consent. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12, 280–289. doi:10.1007/s13178-015-0193-x.

Emmers-Sommer, T. M., Farrell, J., Gentry, A., Stevens, S., Eckstein, J., Battocletti, J., et al. (2010). First date sexual expectations, sexual- and gender-related attitudes: The effects of who asked, who paid, date location, and gender. Communication Studies, 61(3), 339–355.

Guerrero, L. K., Andersen, P. A., & Afifi, W. A. (2013). Close encounters: Communication in relationships (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hynie, M., Lydon, J. E., Coté, S., & Wiener, S. (1998). Relational sexual scripts and women’s condom use: The importance of internalized norms. Journal of Sex Research, 35, 370–380.

Krahé, B., Scheinberger-Olwig, R., & Kolpin, S. (2000). Ambiguous communication of sexual intention as a risk marker of sexual aggression. Sex Roles, 42, 313–337.

Metts, S., & Spitzberg, B. H. (1996). Sexual communication in interpersonal contexts: A script-based approach. In B. R. Burleson (Ed.), Communication yearbook 19 (pp. 49–91). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mills, C. S., & Granoff, B. J. (1992). Date and acquaintance rape among a sample of college students. Journal of the National Association of Social Workers, 37, 504–509.

Mongeau, P. A., & Carey, C. M. (1996). Who’s wooing whom II?: An experimental investigation of date-initiation and expectancy violation. Western Journal of Communication, 60, 195–213.

Motley, M. T., & Reeder, H. M. (1995). Unwanted escalation of sexual intimacy: Male and female perceptions of connotations and relational consequences of resistance messages. Communication Monographs, 62, 356–382.

Muehlenhard, C. L. (2011). Examining stereotypes about token resistance to sex. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35, 676–683. doi:10.1177/0361684311426689.

Muehlenhard, C. L., & Hollabaugh, L. C. (1988). Do women sometimes say no when they mean yes? The prevalence and correlates of women’s token resistance to sex. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 872–879. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.872.

Muehlenhard, C. L., & McCoy, M. L. (1991). Double standard/double bind: The sexual double standard and women's communication about sex. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 15, 447–461.

Muehlenhard, C. L., & Rodgers, C. S. (1998). Token resistance to sex: New perceptions on an old stereotype. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 443–463. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00167.x.

Muehlenhard, C. L., Friedman, D. E., & Thomas, C. M. (1985). Is date rape justifiable? The effects of dating activity, who initiated, who paid, and men’s attitudes toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 9, 297–310.

O’Sullivan, L. F., & Allgeier, E. R. (1994). Disassembling a stereotype: Gender differences in the use of token resistance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 1035–1055.

Osman, S. L. (1998). The token resistance to sex scale. In C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, R. Bauserman, G. Shreer & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (pp. 567–568). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Osman, S. L. (2003). Predicting men’s rape perceptions based on the belief that “no” really means “yes”. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 683–692.

Peterson, Z. D., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (2007). Conceptualizing the “wantedness” of women’s consensual and nonconsensual sexual experiences: Implications for how women label their experiences with rape. Journal of Sex Research, 44, 72–88.

Shotland, R. L., & Hunter, B. A. (1995). Women’s “token resistance” and compliant sexual behaviors are related to uncertain sexual intentions and rape. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 226–236.

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (1984). Sexual scripts. Society, 22, 53–60.

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (1987). Sexual scripts: Permanence and change. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 15, 97–120.

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. H. (2003). Sexual scripts: Origins, influences and changes. Qualitative Sociology, 26, 491–497.

Sprecher, S., Hatfield, E., Cortese, A., Potapova, E., & Levitskaya, A. (1994). Token resistance to sexual intercourse and consent to unwanted sexual intercourse: College students’ dating experiences in three countries. The Journal of Sex Research, 21, 125–132.

Wiederman, M. W. (2005). The gendered nature of sexual scripts. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 13, 496–502.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author is not aware of any conflict of interest involving this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Emmers-Sommer, T.M. Do Men and Women Differ in their Perceptions of Women’s and Men’s Saying “No” When They Mean “Yes” to Sex?: An Examination Between and Within Gender. Sexuality & Culture 20, 373–385 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-015-9330-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-015-9330-1