Abstract

Even when émigrés living abroad versus returning migrants share similar norms, knowledge, practices, and ideas with non-migrants living in their origin country, émigrés have a stronger influence on non-migrants’ political beliefs and behaviors. The reason is that outmigration affects the social ties in which discussions between émigrés abroad and non-migrants are embedded, making them more cohesive and asymmetrical. In contrast, returning permanently to the origin country reverses these effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This article moves the debate about migrants’ effects on home country politics forward by asking how cross-border interpersonal communication influences political behavior among people who do not immigrate. Political behavior is defined widely as citizens’ attitudes toward and participation in public and political life. I compare the effects of long-distance cross-border interactions—between international migrants living abroad (hereafter referred to as émigrés) and people who stay in their origin country (non-migrants)—and face-to-face cross-border interactions—between non-migrants and migrants who return to their origin country permanentlyFootnote 1 (returnees) after living abroad.

Levitt (2001) argues that both long-distance and face-to-face cross-border social interactions serve as a conduit for “social remittances.” That is, cross-border interactions enable both émigrés and returnees (I use the unqualified term “migrants” to refer to both types of migrants) to transmit from their receiving to sending countries the norms, practices, and social capital they have learned or simply observed living abroad, including “principles of neighborliness, community participation and aspirations for social mobility…values about how organizations should work, incorporating ideas about good government and good churches and about how politicians and clergy should behave” (Levitt 2001, pp. 59–61). Furthermore, they contain information about “the kinds of religious rituals they [individual migrants] engage in, and the extent to which they participate in political and civic groups” (2001, pp. 59–61). Levitt notes that migrants who transmit social remittances do not necessarily intend to bring about change; social remittances flow through everyday interactions between ordinary people whose lives have been separated by borders. Furthermore, migrants do not neatly package and send social remittances from their receiving to origin countries, nor do non-migrants simply absorb them; rather they flow through interpretive and deliberative exchanges.

Still, Levitt’s central claim is that cross-border interactions between émigrés, returning migrants, and people who do not migrate occur within a shared social context called a transnational social space, which emerges because international migration sets in motion a cross-border exchange of money, people, ideas, and information that grow sufficiently dense, thick, and widespread that migrants’ sending and receiving communities become inextricably linked (see also Basch et al. 1994; Faist 2000; Levitt and Jaworsky 2007; Mahler 1998; Pries 2001). Faist writes that transnational social spaces are both “socially coherent” and “symbolically integrated” (2000, p. 258). It is in such a transnational context that Levitt claims international migrants introduce new and transformative information into their everyday social interactions with non-migrants.

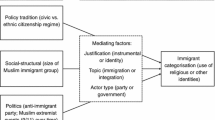

I argue, in contrast, that social remittances flow through interpersonal interactions embedded in distinct social contexts, which in turn affect the degree to which social remittances influence non-migrants. Focusing on the transmission of information, ideas, practices, norms, and behavioral dispositions about politics and public life (a subset of social remittances), I present a framework for understanding the influence of cross-border interactions, which highlights that émigrés living abroad, versus returnees who have permanently resettled in their origin countries, transmit social remittances from distinct structural locations. Concretely, I propose that long-distance cross-border interactions fall under what Kapur (2010) refers to as the diaspora channel, meaning “the impact of emigrants on the country of origin from their new position abroad,” while face-to-face cross-border interactions constitute an aspect of the return channel, meaning the ways in which returning emigrants “affect sending country politics differently than if they had never left” (Kapur 2010, p. 17).

Under this framework, international migrants can influence non-migrants through both channels as a result of the material and human capital they obtain through international migration, consistent with Levitt’s argument. However, the notion of the diaspora channel highlights that émigrés transmit social remittances from a unique structural position within the borders of a foreign receiving state, while the return channel emphasizes that returning migrants do so from inside the origin [nation] state where they live with their non-migrant co-nationals. This framework suggests that the concept of a transnational social space obscures structural factors that fundamentally shape the nature of cross-border interactions and, implicitly, the influence of social remittances.

My emphasis on the structural context in which cross-border social interactions are embedded is consistent with the scholarship on interpersonal interactions and behavioral change. This work broadly concurs that everyday social interactions strongly influence political behavior and beliefs. However, as I explain below, there are debates concerning whether interactions are more influential when they involve people who are close both spatially and temporally or when they involve people who have what Granovetter (1973) refers to as “weak” ties. Furthermore, in tackling this debate, political scientists have generally ignored the influence of international interpersonal social interactions on political behavior,Footnote 2 even though they are fairly prevalent,Footnote 3 and despite the promise their study holds for generating new theoretical insights.

Based on evidence of cross-border communication between Mexicans in the USA and Mexico, this article shows that although émigrés living abroad and returning migrants share similar norms, knowledge, practices, and ideas with non-migrants, émigrés have a stronger influence on non-migrants’ political beliefs and behaviors. Drawing on Levitt’s notion of social remittances, current theories of how everyday social interactions between ordinary people affect political behavior, and Kapur’s (2010) framework, I argue that this is because outmigration affects the social ties in which discussions between émigrés abroad and non-migrants are embedded, altering power relationships between the two, and making them more cohesive. In contrast, returnees have a weak influence as moving back permanently to the origin country reverses these effects.

Theories of Social Interactions and Political Learning: Domestic and Cross-Border Contexts

Experts contend that interpersonal social interactions have an even more powerful influence on political choices than information and opinions conveyed through the media or by political parties (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955; Lazarsfeld et al. 1944; Niven 2004). However, there is some debate as to what types of social interactions are more influential (Huckfeldt and Sprague 1991; Huckfeldt and Beck 1995; Kenny 1994, 1998; Mutz 2002; Quintelier et al. 2012). One perspective is that cohesive social networks, in which individuals interact routinely and face-to-face, are more influential (Burt 1987). Most strikingly, psychologist Bibb Latané (1981) claimed that social impact is proportional to the inverse square of the distance separating two persons. A competing view argues that socially distant interlocutors—meaning people who are not physically proximate and do not regularly see or interact with one—are more influential (Granovetter 1973; Huckfeldt and Beck 1995; Huckfeldt and Sprague 1991; Kotler-Berkowitz 2005).

Scholars who stress the importance of social cohesion depict “social influence in politics as occurring within small groups of close associates who share common understandings that are fostered within the same normative climate of opinion” (Huckfeldt and Beck 1995, p. 1027). Some argue that “intimacy, trust, respect, access and mutual regard” are themselves the source of close interlocutors’ influence (Huckfeldt and Sprague 1995, p. 162). Others claim that repetitive in-person communication is influential because it enables citizens to identify the people they perceive as worthy of emulating (peer opinion leaders; Berelson et al. 1954; Brady and Sniderman 1985; Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955; Lupia and McCubbins 1998; Sniderman et al. 1991). A third group emphasizes that regular in-person interactions generate norms of reciprocity, which in turn enable individuals to encourage one another to participate in politics (Chwe 2000; Klofstad 2007; Putnam 2001).

In contrast, scholars who hold that “weak” social ties are more influential stress the fact that they link individuals who belong to distinct social structures, meaning that they connect people whose lives are tied to different institutional and organizational settings (Granovetter 1973). Building on the observation that the opinions, knowledge, and practices of interlocutors who belong to distinct social organizations tend to differ, while the views of socially cohesive interlocutors tend to be similar, scholars argue that the influence of socially distant interlocutors is due to the diverse perspectives they introduce into conversations. Exposure to new information encourages individuals to reconsider and even modify their own views (Huckfeldt and Beck 1995).

Still, others downplay the content of interactions between interlocutors with weak ties and emphasize instead the nature of the macro-social structures in which their interactions are embedded. For instance, based on evidence that individuals are especially likely to emulate the behaviors and attitudes of centrally positioned—or well-connected actors—even when their personal interactions with them are spare, Marsden (1983) puts forth that power relationships can make weak ties particularly influential. Thus, a person’s social connections or membership in an exclusive social structure can make them influential over others they hardly know.

Significantly, research on interpersonal communication and political behavior has focused almost exclusively on “domestic” social interactions, meaning those between two or more people who live in the same political community, be it the same town, county, state, or nation. What are the implications of these theories for cross-border interactions?

Intuitively, we might expect the influence of face-to-face cross-border interactions to conform to those of socially cohesive “domestic” ones—as if the migrant had never left—since these conversations are typically between people whose pre-migration ties were very close. We might also expect long-distance cross-border interactions to influence non-migrants for the same reasons that socially distant individuals can influence one another since they are between two people located in two, sometimes mutually exclusive, social structures—that is, two distinct nation states. However, the scholarship on migration and diasporas intimates that the degree to which each type of interaction is either socially cohesive or distant is not so straightforward. Émigrés living abroad may remain socially cohesive peer leaders from a distance. Conversely, notwithstanding their renewed physical proximity, there may exist a significant social distance between returnees and non-migrants.

Long-Distance Cross-Border Interactions: Socially Distant or Cohesive?

Long-distance cross-border discussions are to some degree socially cohesive because they happen between émigrés and the people back home with whom they were closest before departing. What is more surprising is that international migration may contribute to sustaining or strengthening reciprocal bonds and to enhancing non-migrants’ perception that émigrés’ political beliefs and behaviors are worthy of emulating.

One reason for this is that outmigration activates the “prospect channel” (Kapur 2010), a concept I modify slightly to encompass the many ways in which having an emigrant friend, family, or household member affects the current choices of people who stay in sending countries. For example, the fact that legal permanent residents and naturalized US citizens can petition for their immediate family members to obtain legal residency in the USA alters the menu of possibilities of those non-migrants who qualify. Additionally, regardless of their legal status, émigrés who send home remittances affect non-migrants’ future choices by extending their years of schooling (Borraz 2005; Edwards and Ureta 2003) and enabling them to spend more on housing (Adams and Cuecuecha 2010). Furthermore, both undocumented and documented émigrés can provide non-migrants access to transnational social capital (Levitt 2001; Portes and Landoldt 2000), a resource that emerges when émigrés connect non-migrants with information and people in the receiving country, such as tips about jobs or export markets, access to capital, or information that facilitates international migration (Portes and Landoldt 2000). In each of these instances, émigrés have a utilitarian value that encourages non-migrants to retain social cohesion with them.

The force behind “prospect” is structural; it is the international system made of hierarchically ordered states whose boundaries enclose distinct economic and governing institutions. The bounded nature of states underpins contrasting national levels of aggregate wealth, education, health, justice, safety, and citizenship (cf. Brubaker 1992; Mann 1984; Walzer 1984). These differences, in turn, make international migration itself a potentially welfare improving strategy; they are inherently tied to an individual’s ability to modify the future choices of people close to them.

Nonetheless, although “prospect” can strengthen social cohesion, long-distance interlocutors cannot overcome some consequences of the fact that they are physically separated from one another. For instance, when émigrés are absent, non-migrants cannot regularly observe them or question their actions and choices. It can become more difficult to enforce norms of reciprocity and regenerate mutual trust and regard.

Current theories suggest that in the context of social distance—or absence—non-migrants may use structural cues to determine how they respond to the social remittances that émigrés transmit. Marsden’s work on how power relationships determine social influence, as well as theories of international diffusion, suggests that regardless of whether émigrés’ presence in the receiving country is clandestine or authorized, and notwithstanding the day-to-day struggles that many migrants face inside the receiving state, their access to a wealthy and more powerful receiving country may make them more influential vis-à-vis non-migrants. Taking this logic into an international context, Hafner-Burton et al. (2009) note that while “[nation] states’ material power is determined by the relative size of their material capital, social power is determined by the relative social capital created by and accessed through ties with other states in the international system” (p. 24). This signifies that the power asymmetries between sending and receiving countries could make migrants located in wealthier and more powerful nations more influential, regardless of the utilitarian benefits they in fact generate for non-migrants. Notably, although this perspective emphasizes international structure too, the mechanism driving influence here is distinct from the utilitarian logic behind prospect. In this case, émigrés’ influence is simply a consequence of their physical position in the international system. It is not due to any measurable, individual resources migrants provide to non-migrants from abroad.

Prospect, Absence, and Face-to-Face Cross-Border Interactions

Returnees, in contrast, can transmit social remittances regularly and face-to-face to the non-migrants with whom they had well-established relationships prior to moving away; they can clarify more extensively than via long-distance communication non-migrants’ questions or concerns about those social remittances; and non-migrants can observe the outcomes of returnees’ actions and choices on a day-to-day basis. Nonetheless, face-to-face cross-border interactions may not clearly fall into the class of discussions embedded in socially cohesive social networks.

Kapur conceives of the return channel as the ways in which returning emigrants “affect sending country politics differently than if they had never left” (2010, p. 17). The concept highlights that although returnees may take up their lives in the origin country where they left off, it is unlikely that they reintegrate as if they had never left. Their experience abroad means that returning migrants may be more likely to introduce substantively new information than socially coherent interlocutors who have not left. Additionally, there is evidence that non-migrants perceive returning migrants as a different category of people—even as “strangers” (Fitzgerald 2009) because their perspectives, behaviors, and values differ from theirs. Fitzgerald refers to the “process of becoming different” as dissimilation, “the forgotten twin of assimilation” (2013, p. 115), and argues that the “differences that develop between migrants and those who stay in Mexico are often much greater than the small difference upon which scholars of assimilation focus their microscope” (p. 115). Notwithstanding their close physical proximity and regular personal interactions, face-to-face interactions between returnees and non-migrants may therefore not be socially cohesive at all.

Social cohesion could also weaken if returnees’ ability to generate “prospect” declines as compared with when they lived abroad. Returning migrants may not generate prospect as they did when they lived abroad, regardless of whether returnees move home willingly or involuntary, if the returns to their human and financial capital are lower back home. Even if they return with greater capital or have a higher capacity to generate prospect for non-migrants, as compared with before they emigrated, non-migrants may be especially cognizant that returnees produce less prospect than when they were abroad.

Furthermore, non-migrants may understand a returnee’s presence in the pre-migration community as a signal that he failed abroad and conclude that he does not possess the knowledge and capabilities to maximize his interests. In the event that non-migrants are aware that a returnee was forcibly removed, did not find work in the receiving country, struggled to adapt socially and culturally, or otherwise found the cost of life abroad too high, then we might expect non-migrants to question whether returnees are worthy peer opinion leaders.

Non-migrants’ perceptions of returnees as failures may also be driven by structural factors that have nothing to do with the true reasons migrants move home. Just as émigrés’ presence in a stronger and wealthier country could make them more powerful and influential, their renewed presence in the origin country could weaken their influence since the structural distance that exists between cross-border interlocutors when migrants are absent shrinks after returnees resettle again among non-migrants.

In sum, I propose that long-distance cross-border interactions, which are part of the diaspora channel, have a stronger influence on the political beliefs and behaviors of non-migrants than face-to-face interactions, which are an example of the return channel. Concretely, I anticipate that émigrés will be influential because they introduce new information to non-migrants and because both their ability to generate prospect and their position in the international system strengthen their social cohesion and power relative to non-migrants. In contrast, I expect returnees to have a weak influence even though they introduce new information because the changes they experience abroad undermine social cohesion; they do not generate as much prospect as they did (or could) abroad, and return obviates the structural significance of absence.

Evaluating Cross-Border Discussions in the Case of Mexican Migrants to the USA

I explore the propositions outlined above in the case of cross-border discussions between Mexican non-migrants and migrants to and from the USA. This case is ideal for a number of reasons. Both types of cross-border interactions are prevalent in Mexico. According to the 2008 Americas Barometer survey taken in Mexico, about one in four Mexicans living in that country engages in cross-border discussions with a family member who lives outside of the country. In 2005, an estimated 73 % of Mexicans in the USA called their relatives at home at least every week, and 82 % of their phone calls lasted more than 20 min (Orozco, et al. 2005). Face-to-face cross-border discussions between returning migrants and people who have never left their country are also widespread since more than one in ten household heads currently residing in Mexico has lived outside of their country in the past (MMP134, mmp.opr.princeton.edu), and approximately 400,000–500,000 migrants return home each year (Campos Vázquez and Lara Lara 2011).

Additionally, while Mexico and the USA have significant power and wealth asymmetries, the physical proximity and ease of movement and communication between the two countries provides the ideal conditions for migrant transnationalism. If cross-border discussions flow across transnational social spaces anywhere—that is, if they bridge nation–state boundaries enough to obviate structural differences, as some scholars contend—it would be in the Mexican case. At the same time, the hierarchical relationship and state boundaries between Mexico and the USA are sufficiently marked that we can reasonably expect them to shape the nature of cross-border interactions in this case, if such structural factors matter at all.

This analysis is based on 138 semi-structured interviews with 40 migrants living in the USA, 31 return migrants living in Mexico, and 67 non-migrants in Mexico who communicate with migrants. All respondents were over the age of 18 and either Mexican citizens or born in the USA to Mexican citizen parents. Most of the interviews with returning and non-migrants were conducted in the states of Tlaxcala and Puebla. Émigrés living in New York, California, Boston, Colorado, Indiana, Rhode Island, and Virginia responded via phone or e-mail exchanges.Footnote 4

Studies of individual-level political behavior rarely employ in-depth interviews with small numbers of respondents, yet my approach is appropriate. Panel data that measure non-migrants’ attitudes both before and after they begin to engage in either of the two types of cross-border social interactions would be ideal for this project, but are difficult to obtain. Cross-national comparisons based on a large sample of Mexican citizens living in Mexico (Bravo 2009; Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow 2010) overemphasize outcomes at the expense of process and theory. Indeed, the present study was inspired, in part by Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow’s (2010) surprising finding that the political behaviors of non-migrant Mexicans who have friends and family abroad differ from those of non-migrants without such ties, while the political behaviors of returning migrants do not.Footnote 5 This finding, which is based on data obtained through a nationally representative survey taken in Mexico, not only suggests that the influence of returning migrants who engage in cross-border interactions with non-migrants may differ from that of émigrés who interact from abroad with non-migrants, but also begs explanation. I therefore use information from field interviews to build on current research suggesting that émigrés and returning migrants may have potentially uneven influences on the political beliefs and behaviors of people who do not migrate and to develop a coherent explanation of why.

To this end, I draw on the in-depth field interviews to conduct process tracing, meaning to evaluate the process leading to an outcome to determine whether each step along the way conforms to the expectations generated by the theory under consideration (George and Bennett 2005). In the following pages, I begin by describing the “outcome” I observed. That is, what political beliefs and behaviors do émigrés and return migrants transmit and what do non-migrants “learn”? Subsequently, I evaluate the process leading to this outcome by exploring, as George and McKeown (1985) suggest, “the stimuli the actors attend to; the decision process that makes use of these stimuli to arrive at decisions; the actual behavior that then occurs; [and] the effect of various institutional arrangements on attention, processing, and behavior” (p. 35), paying careful attention to the theoretical expectations I put forth in the first part of this article.

The Content of Long-Distance Cross-Border Interactions

Mexican émigrés and their co-nationals still living in Mexico reported engaging extensively in cross-border communication. Nearly all émigrés (95 %) communicated via phone calls. The average frequency was once per week. Fifty percent stated that they visit Mexico at least once annually.Footnote 6 These findings are consistent with other data on long-distance cross-border communication.Footnote 7

When asked to rank order a list of discussion topics,Footnote 8 participants who engaged in long-distance interactions indicated: (1) the well-being and health of the family; (2) everyday life in the USA; (3) future plans (both migrant and non-migrant); (4) the economic and security problems that currently plague Mexico; and, (5) US immigration policy (other). Answers (4) and (5) have clear political dimensions, yet when asked directly, Mexican émigrés did not report that political affairs in either Mexico or the USA featured prominently among the subjects they discuss.Footnote 9 Additionally, for the most part, they claimed that they never seek to influence the political choices of non-migrants, and most claimed that they do not initiate discussions about politics.

Despite these claims, my analysis of participants’ open descriptions of the content of their long-distance conversations revealed that 85 % of the émigrés did, in fact, share with non-migrants their understandings of and experiences with public and political life in the USA, including norms, values, and practices. The “political” content can be grouped into four categories: (1) support for institutions; (2) civic responsibility; (3) respect for the rule of law; and (4) respect for individual human rights. Significantly, these are not unlike the types of social remittances Levitt (2001) depicts in her study of cross-border interactions between Dominicans who migrate to the Boston area and the non-migrant residents of Miraflores.

An example of support for institutions involves a college-educated male immigrant who indicated that he spoke with his co-nationals at home about how, “We [Mexican citizens living in Mexico] avoid institutions such as the police…[yet] these [institutions] are vital in the US and very much part of daily life. This has changed my perception of how important these institutions are. And I now think it is our responsibility to make these institutions part of Mexico’s daily life as well.” Another male migrant with a high school education said he shared with non-migrants that “it is amazing how much American bureaucrats and police are at the service of the people. Of course there are the problems with the police that we see on the news and all that, but overall, the public servant in the US is different. The police and the bureaucrats want to help the public, not just themselves.”

References to individual civic responsibility include an undocumented female with a middle school education who said she told people in Mexico about the “value of volunteering.” She shared, “how volunteering can even help improve the economy…my sister here [in the US], now she takes care of kids voluntarily so that their moms can go to work. They help each other get ahead. This never happens in Mexico, [because] people don’t volunteer to help outside the family.” Another woman, who arrived in the USA with a primary school education, but has since completed high school, said she tells her family about how she—not the government—took responsibility for her education. “I saved the money from my job to pay for my studies. I investigated about the opportunities and went after them. The government here [in the US] provides a lot of opportunities, but you yourself have to pursue them.”

Examples of respect for the rule of law include a college-educated woman who stated that she has conveyed home her amazement at the seriousness and care with which Americans prepare and submit their tax returns. She has told her friends and kin in Mexico that, “Paying taxes is something that most Americans think you should do. It is something that they are very aware of. Nobody obligates them.” Another individual noted, “I have told people in Mexico about how people here know the laws; they are aware of what the law says. We need to do that too. It’s something we can do to make the law more important.”

Migrants also convey their understanding that Americans and their government seem to make considerable efforts to protect the rights of minorities. For instance, one college-educated woman said she discussed “how my job here at the university is to look out for the rights of minorities and I compare the situation here to that of indigenous people and women in Mexico. A lot more can be done to protect minority rights in Mexico.” Another undocumented woman with a primary education related that her adult brother, who lives in Mexico and has a learning disability, is not economically active, in contrast with many people with disabilities in the USA. “I am always telling my parents that it is possible for adults with disabilities to work and become more independent. They can have lives that are almost normal. They can contribute to the economy.”

The Content of Face-to-Face Interactions

Returnees also share with non-migrants the new beliefs and behaviors they obtained through experiences and observations in the receiving country. Of the returnees, 87 % indicated that they had learned and imported into Mexico new beliefs from the USA. Additionally, 52 % of returnees indicated that they modeled through their actions in the origin country at least one new value or form of civic engagement that they had learned or observed abroad. Furthermore, returnees were significantly more likely than émigrés to ask non-migrants to participate in public and political life in ways that would be new to them. Most strikingly, however, a full 80 % of returnees who claimed that they had undertaken new forms of civic engagement after returning also reported that they had renounced these new practices within 2 years of moving home.

The social remittances that returnees initially transmitted included support for individual rights, political efficacy, and support for the rule of law, much like those sent by émigrés. Nearly all returnees immediately reentered their country of origin with an enhanced sense that they can personally contribute to bringing about political change (political efficacy).Footnote 10 The following are examples of ideas about political efficacy that they claimed to share with non-migrantsFootnote 11:

-

“Government and society should support private initiatives. Here in Mexico, people consider any initiative a threat.”

-

“Now I don’t just let things happen or wait for the government to fix them, now I try to fix my own problems.”

-

“I learned to be more critical of government—to have more opinions about what my government is doing for me. It can be beneficial.”

-

“Working as a team rather than for myself. People should organize themselves to fix things that are not working, not just worry about their own affairs and let the government take care of everything else.”

-

“I can become politically active without going through a political party. I am interested in participating in politics without joining a party.”

-

“I learned that people here [in Mexico] need to know how to ask the government for things. We have to knock on doors to get things done. We can’t always wait until the government does things.”

Additionally, about one fourth of returning migrants also stated that they returned home believing it is important for the government to protect the rights of women, people with disabilities, and different racial groups. Some notable examples include:

-

“Now I have much respect for people with physical and mental disabilities.”

-

“I learned that I can get along well with Blacks, because I worked with them on the tobacco farms. I never in my live imagined that I would have Black friends.”

-

“I learned that nothing [bad] happens if a country has people of different races—Blacks, Chinese.”

-

“I have seen that men and women can work the same. Now I believe there is not much of a difference between men and women.”

-

“I learned tolerance and respect for people who think differently from me…When I returned, I was surprised by the social discrimination that exists in Mexico.”

The third most common area of new political beliefs and behaviors involved attitudes toward the rule of law. One man from Tlaxcala explained that he “Learned how labor rights are part of a legal system that works well and that there are many groups interested in helping laborers whose rights have been violated. People don’t help each other that way here…nobody respects the law, especially employers.” Another noted that he now believes “The community has a role in ensuring safety, not just the police.” And many participants independently echoed one man’s claim that he had “learned the habits of a good citizen, like respecting others and the laws.” Participants in each of these cases claimed that they had shared these new perspectives with non-migrants.

Returnees’ experiences abroad also motivated new forms of civic engagement. For instance, one male respondent who played soccer professionally prior to emigrating without documents became deeply involved with organized sports in the USA, both as a coach and player. He then married a female US citizen. When he returned to Mexico, he started a women’s recreational soccer club in his hometown. He asserts that although gender norms have changed in Mexico, he does not believe he would have considered starting the women’s team if he had not moved abroad and met women who are involved in organized sports. Another young male who worked as a police officer both before emigrating and after being deported to Mexico explained, “I tried to start an Alcoholics Anonymous club here. There are many drunks here. I belonged to AA there [in the US]. I tried to explain to the people here about the problems with alcohol, especially to the young people.” One retired man who had completed graduate studies in the USA, and lived there for 30 years prior to moving back to Mexico, volunteered to translate into English the signs and information posted in the local museum. Various returning migrants noted that they modeled picking up garbage and putting it in a garbage bin, as opposed to on the ground. One farmer stated that since returning he has run for elected office twice and won once. He claimed that he would never have considered participating in politics in an official capacity prior to leaving, but now believed, “if you want things to change, you have to do it yourself.”

More importantly, perhaps, returnees were much more likely than émigrés to invite their non-migrant co-nationals to become civically engaged. They asked others to help them improve the quality of the roads, enhance public lighting, paint the public school, and keep the town clean and organized. At least one third of returnees endeavored to work with non-migrants to modernize their town’s annual fair.Footnote 12

Notwithstanding these new attitudes and forms of engagement, 2 years after moving home, only 12 % of returning migrants claimed that they practiced or discussed with others the forms of civic engagement they had learned in the USA (except in some cases with their children). Eighty percent of those who had engaged in new forms of engagement claimed that after 2 years, their participation had declined to pre-migration levels or lower and that they had stopped enjoining others to work with them in the public realm.

What Non-migrants “Learn”

Table 1, below, lists some examples of the actions in which non-migrants reported engaging as a result of their communication with Mexicans living abroad. These are classified into six categories that broadly reflect the behaviors and attitudes émigrés claim to share via cross-border conversations. Significantly, these are consistent with the outcomes reported in large-n studies of how outmigration affects the political behaviors of non-migrants (Córdova and Hiskey 2010; Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow 2010).

In contrast, non-migrants universally indicated that they did not embrace the beliefs and behaviors transmitted by returning migrants. Rather, they rejected the ideas about public life that returnees shared with them. This result is surprising given returnees’ proclivity for asking others to participate and in light of robust evidence from studies conducted in the “domestic” context that personal invitations strongly affect peoples’ decisions to engage civically (Niven 2004; Klofstad 2007). However, as I show below, the result is consistent with the theoretical expectations I developed in the first part of this article.

The Paradoxical Strength of Long-Distance Interactions

Non-migrants were not responsive to the political beliefs and behaviors that returnees conveyed. In contrast, they either carefully considered or fully embraced social remittances when émigrés transmitted them. What explains this paradoxical outcome? Here, I show that long-distance interactions are influential because émigrés’ presence in a more powerful receiving country elicits feelings of empathy and pride, which in turn buttress social cohesion; furthermore, the prospect that migrants create while they are abroad strengthens these ties.

Non-migrants repeatedly expressed empathy toward émigrés, whom they understood to be living as outsiders or suffering hardship on the margins of US society. More than 70 % shared the view that it is extremely difficult for émigrés to find work in the USA and lamented that their co-nationals must work particularly hard once they find a job. Interestingly, non-migrants shared this view regardless of whether the émigrés with whom they interacted worked in high- or low-skilled jobs. Over half of non-migrants claimed that US employers exploit their émigré family members and friends.

In discussing their interactions with émigrés, about 70 % of non-migrants also mentioned the dangers associated with crossing the USA–Mexico border clandestinely, as well as their concerns that the émigrés with whom they interact would be apprehended by immigration authorities. Furthermore, 85 % expressed with great certainty that their emigrant friends or kin, and Mexicans in the USA in general, were subject to racial discrimination. Coverage in the Mexican press of some of the more injurious consequences of emigration to the USA, such as death at the border and the deportation of Mexican parents without their minor US citizens, as well as the discourse of Mexican public officials may have contributed to strengthening this sentiment, even among Mexican citizens without direct ties to migrants.

Other sources of empathy included that the emigrant was “out there, alone, and the family is here” and concerns about the challenges of adapting to new foods, a different language, and a different housing situation—“everything is different over there.” In sum, taken together, the non-migrants in my sample held strong empathetic sentiments toward émigrés because they understood their situation in the receiving country as challenging for reasons attributable to structural forces beyond their control.

These empathetic sentiments reflect broader trends in Mexican public opinion of the USA as a dominant and closed nation state, particularly vis-à-vis Mexican migrants. A national public poll taken at around the time of my field work indicates that 49 % of Mexicans perceive American citizens as a little bit to fully intolerant, 73 % believe that they are either racist or very racist, and 63 % believe that the reason the USA is wealthier than Mexico is that it exploits the riches of others (CIDAC-Zogby 2006).

A paradoxical extension of these shared beliefs about the receiving society is that that those Mexicans who “get in” to the USA may be seen as especially capable. Consistent with this expectation, my field interviews reveal that while non-migrants perceived the situation of their friends and kin in the receiving country as precarious, émigrés’ achievements within that receiving country context elicited fierce pride.

About 20 % of the non-migrants with whom I spoke showed me (unsolicited) pictures of their emigrant friends and kin at US school graduations, in front of major US monuments, and with their new USA-based family. As they shared these, they described their family members as noble, hard-working individuals who were responding to the family’s social and economic needs—individuals whose choices were shaped by macroeconomic forces beyond their control (the fact that the Mexican government had developed a public discourse that depicted migrants to the USA as self-sacrificing national heroes may have enhanced these sentiments). About 60 % of non-migrants referenced achievements by the émigrés with whom they interact (i.e., job promotions, academic awards, athletic achievements, enrollment in school, taking a “luxury” vacation, adjustment of immigration status, purchasing a car or home, starting a business, marrying a foreigner).

This sense of pride intimates that non-migrants value émigrés’ access to (presence in) the dominant and closed receiving nation-state. For non-migrants who engage in cross-border interactions, an émigrés’ achievements in a receiving country that discriminates, polices, and exploits immigrants are an indicator of good social standing; it signals that the émigré is particularly capable.

Notwithstanding this structural argument, non-migrants’ narratives also strongly suggest that utilitarian considerations enhance émigrés’ influence. In particular, the fact that émigrés’ presence abroad affects the current choices and opportunities of non-migrants—that is, the fact that outmigration activates the “prospect” channel—matters, too. Various respondents showed me the changes they had made in their homes with the money they received from a migrant living in the USA. About 20 % of respondents indicated that their children are completing more schooling than any family member before them as a result of the cash remittances their family member sends home, and nearly half said they had used remittances to purchase medicines or other health care expenses. Additionally, all of the women with spouses in the USA indicated that their husband would be “fixing the papers” so that she could join him there in the future.

The previous narratives reflect well-documented research that as émigrés contribute to stabilizing the origin household’s income, generating greater savings for the household’s future, and helping to insure the origin household against risk (Wong et al. 2007), people who do not move away take on responsibilities that émigrés abandon (e.g., taking care of land, businesses, animals, children, and the elderly; Cohen 2001; Conway and Cohen 1998; Massey 1990; Massey et al. 1993; Warnes 1992). They affirm the claim that émigrés and non-migrants share the burdens and benefits of migration and suggest that non-migrants are particularly receptive to émigrés because the latter’s absence represents a unique situation during which the menu of possibilities expands for the former. Émigrés’ ability to generate prospect thus motivates non-migrants to uphold household-level reciprocal obligations and to remain socially cohesive, despite major distances. Furthermore, the empathy and pride that non-migrants feel toward émigrés is likely deeply tied to these reciprocal obligations and the tangible benefits émigrés generate for them from their position abroad. Taken together, these forces encourage non-migrants not only to remain in close contact with émigrés but also to see them as siempre presentes—always present (c.f. Smith R. 2006).

Face-to-Face Interactions: Weak Social Cohesion and Limited Structural Advantages

Many migrants who had moved home intending to resettle in Mexico engaged in and enjoined others to participate in new political behaviors after returning. They believed that their new practices could contribute to improving public and political life in their origin community. Yet, shortly after moving back, many returnees stopped engaging in these practices and generally withdrew from public life. Furthermore, non-migrants did not embrace what returnees shared with them. What explains this pattern? And what does it tell us about the influence of face-to-face interactions?

Table 2 below lists quotations from interviews with each of the returning migrants who engaged in new forms of participation after moving home and then subsequently abandoned these new practices.

In every case, returnees stated that they “lacked support” from non-migrant friends and kin for their new behaviors. None said they stopped engaging in new behaviors or beliefs because they faced formal institutional constraints. There was no evidence that their new practices put them at risk of suffering physical harm or loss of liberty. Instead, both returnees who were forcibly removed from the USA and those who moved home voluntarily (to invest their savings in property and businesses, reunite with family, because their visa had expired, for employment, or as retirees) reported that they stopped engaging in new forms of engagement because of what they perceived as ill-will among non-migrants.

Furthermore, non-migrants corroborated that they did not receive returnees well. About 30 % believed that their opinions of and social ties with returnees had not changed as a result of their experience abroad; however, the remaining 70 % reported that returnees not only changed abroad but also import more problems than benefits.

The differences in non-migrants’ attitudes toward returnees and émigrés are striking. Rather than elicit empathy, the challenges that returning migrants face when they resettle in the origin country invoke disdain among non-migrants. Similarly, whereas an émigré’s adaptation and achievements in the exclusive receiving country are a source of pride, the ways in which returnees changed (adapted to the USA) during their time abroad are a source of embarrassment, disappointment, and even alienation. Non-migrants’ negative reactions to returnees, in turn, contribute to undermining social cohesion.

About 40 % of non-migrants noted that returnees do not adapt well to living with the family again. One woman said that her husband, who had not found a job upon returning to Mexico, was good for nothing since he had come home; “there is no work,” she explained. In contrast to the empathy that émigrés’ struggle to find employment in the USA elicited, there was a tendency to cast returnees who struggle to find productive work in Mexico as lazy and inept.

Non-migrants also affirmed that there exist some of the problems Fitzgerald (2013) attributes to dissimilation. For example, the parents of a handful of returnees who had brought home non-Mexican partners or who returned with children who did not speak Spanish when they arrived felt not only disappointed but also alienated from their migrant offspring. Consistent with FitzGerald (2009) and Coutin (2007), over half of non-migrants complained that returnees came home with what are popularly perceived of as American vices, such as disrespect for authorities, weak family ties, and a higher consumption of drugs and alcohol. Two participants shared that they had divorced in large part as a result of the changes in their spouse after he moved home.

The changes that invoked criticism included that the ideas and information returning migrants remit concerning political and public life are too idealistic. About half of the local nonmigrant leaders (six participants) in the sample indicated that returnees come home with illusions of empowerment and having forgotten how things get done in Mexico. Over 50 % of non-migrants also claimed that when returnees entreat them to become involved in public life in ways that are new to them, they are signaling that they no longer value or understand their own culture or local knowledge and practices.

Even though returnees may also merit the empathy that non-migrants believe émigrés warrant, they do not invoke non-migrants’ good will because non-migrants do not understand returning migrants’ hardship within Mexico as a consequence of US dominance and marginalization. Rather than attribute returnees’ struggles to broad structural forces, non-migrants blame individual agency. At the same time, the fact that returnees are no longer in the receiving country means that they no longer occupy a social position of power in non-migrants’ eyes. Returnees’ demonstrated ability to enter, adapt to, and then exit a dominant and closed receiving country does not evoke sentiments of pride or indicate that an individual’s actions and choices are worthy of emulating the way entering, adapting, and remaining there does.

While non-migrants might rightfully ask themselves whether an individual who returned because she failed to meet her expectations abroad is worthy of emulating (i.e., If this person has such a strong knowledge of how to get ahead in the host country and such admiration for how public and political life functions there, why did he come home?), the fact that the non-migrants in my sample demonstrated ill-will toward returning migrants, regardless of whether they were deported or came home with significant savings, suggests that they interpreted a migrants’ return for whatever reason as an indication that they are not worthy of emulating. As above, this suggests that physical location affects non migrants’ perceptions in ways that are outside of the returnees’ individual control.

Furthermore, non-migrants’ repeated comments about returnees’ failure to generate income in Mexico reveal that the former believe that the latter do not generate as much prospect as when they are abroad. More than half of non-migrants complained that returnees live off the earnings they made in the USA rather than work after they return. Moreover, about as many non-migrants resented that returnees believed anything could be purchased or resolved with the mighty dollar. Such comments came from people who benefitted from remittances prior to the migrants’ return. They suggest that whereas the money and resources émigrés sent home encourage non-migrants to sustain their reciprocal obligations, a migrant’s return with money ruptures this mutually agreeable household-level strategy in ways that undermine social cohesion. Whereas reciprocal obligations and the benefits they imply for non-migrants make them particularly attentive to émigrés, migrants’ returns, albeit with savings, do not produce these effects. Indeed, one non-migrant noted indignantly that returnees are “surprised at how busy we all are—they think we have time to sit down and talk.”

This analysis supports the proposition that it is not so much the content of what migrants share but rather the location from which they communicate that matters. Face-to-face cross-border interactions are not as influential as long-distance ones because the relationships in which the former are embedded become socially distant. Social cohesion declines between returnees and non-migrants because the former no longer generate prospect and because having adapted to living in a more powerful, dominant, and wealthy country creates feelings of alienation rather than pride. The resulting lack of social cohesion weakens returning migrants’ influence even though they share potentially useful social remittances with non-migrants after they return.

Conclusion

This article compares the influence of long-distance and face-to-face cross-border interactions on the political beliefs and behaviors of non-migrants. It shows that migrants’ potential to influence non-migrants via the return channel differs from their ability to do so via the diaspora channel even though the norms, knowledge, practices, and ideas that both émigrés and returning migrants share with non-migrants are highly similar. The reason is that the social ties in which discussions between émigrés abroad and non-migrants are embedded are more cohesive and asymmetrical. In contrast, returning permanently to the origin country reverses these effects.

The fact that returnees do not strongly influence people who stay at home is inconsistent with “domestic” social cohesion theories of political behavior, which imply that non-migrants would be particularly receptive to the new, more heterogeneous ideas and practices imported by the returnees with whom they interact routinely and in person. That émigrés are more influential despite their social and physical distance is more in line with perspectives which hold that structure—in this case the international system—affects the relative influence of individual agents.

This article therefore shares Waldinger and Fitzgerald’s (2004) skepticism toward accounts of migrants’ cross-border relations that downplay the significance of borders. As such, it provides a more nuanced account than Levitt of how social remittances affect people who stay behind. Levitt’s perspective illuminates the influence of a limited number of actors who do not fall neatly into the binary categories of émigrés or returnees; they are “neither here nor there.” However, most people who engage in cross-border interactions are rather more unequivocally situated either at home or abroad (Waldinger 2008, 2009). Moreover, the findings presented here suggest that non-migrants are keenly aware that international migrants move between nation states whose social closure structures opportunities and power relations; indeed, non-migrants seem to reify the significance of state borders. This would not be the case if émigrés, returnees, and their friends and kin who stay at home interacted within a coherent transnational social space.

Despite these significant contributions, my research has limitations that open up important questions for future research. These preliminary results require further validation within Mexico on a larger and nationally representative sample. Additionally, my conclusions merit further exploration beyond the Mexican case. Itzigsohn and Saucedo (2002) demonstrate persuasively that “there is more than one causal path that can account for the rise of transnational social practices” and that these “can be explained by reference to the context of [receiving country] reception and the mode of incorporation of each [national] group” (p. 766). My research suggests that the sending country or community context, particularly shared understandings of the implications of outmigration and return, can also affect transnational practices and their effects. It is therefore worth exploring how non-migrants from countries where the social, historical, and economic forces around migration differ from the Mexican case respond to the information and ideas that migrants share.

Notes

Many individuals who move back to their origin country intending to settle ultimately remigrate. Others migrate and return numerous times. Knowing the contingent nature of migrants’ choice to move home permanently, my intention is to distinguish between those who move home to live as opposed to those regularly or sporadically travel to their origin country for business or visits.

Cross-border interactions between migrants and non-migrants do not comprise all international interpersonal interactions, but their prevalence is striking. In 2008, about 30 % of the voting-age citizens living in Latin America reported that they communicated with family members living outside their country at least once a week (Americas Barometer 2008). Nearly 70 % of Dominicans, Cubans, Salvadorans, Mexicans, and Colombians living in the USA phone home weekly (Soehl and Waldinger 2010); between 10 and 25 % of Guatemalans, Salvadorans, Hondurans, Bolivians, Haitians, and Guyanese do so everyday (Americas Barometer 2008), and, among Mexicans in the USA, 82 % of phone calls home last more than 20 min (Orozco et al. 2005).

My sample sacrificed representativeness in favor of diversity. For each type of respondent—émigrés, returning migrants, and non-migrants—I selected as diverse a sample as possible along both independent and dependent variables of theoretical interest. In selecting émigrés, I sought diversity along two dimensions: personal attributes (education, English language skills) and conditions of emigration (reason for leaving, duration of their stay). In selecting returning migrants, I considered a third dimension: condition of return (forced or voluntary repatriation and return to community with high or low levels of emigration). These three dimensions have the potential to affect one or more of the following: (1) migrants’ ability to learn new political beliefs and behaviors in the USA (Bean et al. 2006) and propensity to discuss politics across borders (McCann et al. 2007); (2) migrants’ levels of interest in importing change to their sending community and perceptions of non-migrants toward migrants. In selecting non-migrants, I sought diversity on those dimensions known to shape political beliefs and behaviors, including age, education, income, and interest in politics. For more details about the sample, consult the technical appendix at https://bates.academia.edu/PerezArmendarizClarisa.

Pérez-Armendáriz (2009) further shows that communication between migrants and non-migrants influences the latter’s political behaviors, while return migrants’ behaviors do not.

Note that return visits are a form of long-distance interaction since migrants remain settled in the receiving country.

I have described the prevalence earlier in this paper. Outside of Mexico, about 30 % of the voting-age citizens of Latin America communicated with family members living outside of their country at least once a week (The Americas Barometer 2008). Between 10 and 25 % of Guatemalans, Salvadorans, Hondurans, Bolivians, Haitians, and Guyanese communicated everyday (The Americas Barometer 2008).

I asked participants, “What do you mainly talk about with your friends and family? Please write the number 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 next to the topics of conversation that you discuss with your family in order of importance. For example, if when you speak with your friends or family living in the USA you talk with them more than anything about the people’s health and well-being, then write a one (1) next to that response below. You should mark only five responses, each with a different number.” The choices where, “other (please explain); employment possibilities in the USA; political affairs in the USA; political affairs in Mexico; your daily life in the USA; your job in the USA; future plans; the economic situation of the family and household expenses; the Mexican economy; your family’s health and well-being.”

In my discussions with respondents, I learned that most understood discussions about politics narrowly, as specifically about elections; particular candidates; institutions such as the presidency, parties, the legislature, and electoral authorities; and political scandals. Large-n survey studies such those by Bravo (2009), which ask respondents whether they talk to émigrés about politics, may thus underestimate the volume of cross-border political discussions.

The difference between civic responsibility and political efficacy is between citizens’ belief that they can, versus should, engage in certain types of activities, with the latter representing responsibility.

I asked participants: “Do you think your ways of thinking or seeing things changed as a result of having emigrated to the USA? Or, do you think that they did not change at all? Explain. If respondents claimed that their ways of seeing or thinking had change, I asked if they had conserved your new ways of thinking? Since you returned, have you shared your new ways of thinking with friends, family, or people at work?”

Note that these returnees did not belong to a formal hometown association or migrant club.

References

Acharya A. How ideas spread: whose norms matter? Norm localization and institutional change in Asian regionalism. Int Organ. 2004;58(2):239–75.

Adams R, Cuecuecha A. Remittances, household expenditure and investment in Guatemala. World Dev. 2010;38(11):1626–41.

Basch L, Blanc-Szanton C, Schiller N. Nations unbound: transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments, and deterritorialized nation-states. London: Gordon and Breach; 1994.

Bean FD, Brown SK, & Rumbaut RG. Mexican immigrant political and economic incorporation. Perspectives on Politics, 2006;4(02):309–13.

Berelson B, Lazarsfeld P, McPhee W. Voting: a study of opinion formation in a presidential campaign. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1954.

Borraz F. Assessing the impact of remittances on schooling: the Mexican experience. Glob Econ J. 2005;5(9):1–30.

Bourdieu P. Distinction: A social critique of the judgment of taste Harvard University Press; 1984.

Brady H, Sniderman P. Attitude attribution: a group basis for political reasoning. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1985;79(4):1061–78.

Bravo J. Emigración y compromiso político en México. Política y Gobierno: Volumen Tematico 2009; 273–310.

Brubaker R. Citizenship and nationhood in France and Germany. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 1992.

Burt R. Social contagion and innovation: cohesion versus structural equivalence. Am J Sociol. 1987;92(6):1287–335.

Campos Vázquez RM, Lara Lara J. Self selection patterns among return migrants: Mexico 1990-2010. 2011. Paper provided by El Colegio de México, Centro de Estudios Económicos in its series Serie documentos de trabajo del Centro de Estudios Económicos with number 2011-09. Retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/p/emx/ceedoc/2011-09.html#biblio.

Checkel JT. International norms and domestic politics: bridging the rationalist–constructivist divide. Eur J Int Relat. 1997;3(4):473–95.

Chwe MS. Communication and Coordination in Social Networks. Rev Econ Stud. 2000;67(1):1–16.

CIDAC-Zogby. Encuesta: México y Estados Unidos. Cómo miramos al vecino. Mexico, D.F.: Centro de Investigación para el Desarrollo en México; 2006.

Cohen J. Transnational migration in rural Oaxaca, Mexico: dependency, development, and the household. Am Anthropol. 2001;103(4):954–67.

Conway D, Cohen J. Consequences of migration and remittances for Mexican transnational communities. Econ Geogr. 1998;74(1):26–44.

Córdova A. & Hiskey J. Migrant Networks and Democracy in Latin America. Unpublished working paper, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN; 2010

Coutin S. Nations of emigrants: shifting boundaries of citizenship in El Salvador and the United States. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 2007.

Edwards AC, & Ureta, M. International migration, remittances, and schooling: evidence from El Salvador. J Dev Econ. 2003;72(2);429–61.

Elkins Z. Constitutional networks. In: Kahler M, editor. Networked politics: agency, power, and governance. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 2009. p. 43–63.

Faist T. The volume and dynamics of international migration and transnational social spaces. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.

FitzGerald DS. A nation of emigrants: how Mexico manages its migration. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2009.

FitzGerald DS. Immigrant impacts in Mexico: a tale of dissimilation. In: Eckstein SE, Najam A, editors. How immigrants impact their homelands. Durham: Duke University Press; 2013. p. 114–37.

George A, Bennett A. Case studies and theory development in the social science. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2005.

George A, McKeown T. Case studies and theories of organizational decision-making. In: Coulam R, Smith R, editors. Advances in information processing in organizations, vol. 6. Greenwich: JAI Press; 1985. p. 21–58.

Granovetter MS. The strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol. 1973;78:1360–80.

Hafner-Burton EM, Kahler M, Montgomery AH. Network analysis for international relations. Int Organ. 2009;63(3):559–92.

Huckfeldt R, Beck P. Political environments, cohesive social groups, and the communication of public opinion. Am J Polit Sci. 1995;39(4):1025.

Huckfeldt R, Sprague J. Discussant effects on vote choice: intimacy, structure, and interdependence. J Polit. 1991;53:122–58.

Huckfeldt R, Sprague J. Citizens, politics and social communication: information and influence in an election campaign. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

Itzigsohn J, Saucedo SG. Immigrant incorporation and sociocultural transnationalism1. Int Migr Rev. 2002;36(3):766–98.

Kapur D. Diaspora, development, and democracy: the domestic impact of international migration from India. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2010.

Katz E, Lazarsfeld P. Personal influence. Glencoe: The Free Press; 1955.

Kenny C. The microenvironment of attitude change. J Polit. 1994;56(3):715–28.

Kenny C. The behavioral consequences of political discussion: another look at discussant effects on vote choice. J Polit. 1998;60(1):231–44.

Klofstad C. Talk leads to recruitment: how discussions about politics and current events increase civic participation. Polit Res Q. 2007;60(2):180–91.

Kotler-Berkowitz L. Ethnicity and political behavior among American Jews: findings from the National Jewish Population Survey 2000–01. Contemp Jew. 2005;25:132–57.

Latané B. The psychology of social impact. Am Psychol. 1981;36(4):343.

Lazarsfeld P, Berelson B, Gaudet H. The people’s choice: how the voter makes up his mind in a presidential campaign. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce; 1944.

Levitt P. The transnational villagers. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2001.

Levitt P, Jaworsky B. Transnational migration studies: past developments and future trends. Annu Rev Sociol. 2007;33(1):129–56.

Lupia A, McCubbins M, editors. The democratic dilemma: can citizens learn what they need to know? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

Mahler S. Theoretical and empirical contributions toward a research agenda for transnationalism. In: Smith M, Guarnizo L, editors. Transnationalism from below. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers; 1998.

Mann M. The autonomous power of the state: its origins, mechanisms and results. European Journal of Sociology; 1984;25(02):185–13.

Marsden PV. Restricted access in networks and models of power. Am J Sociol. 1983;88(4):686–717.

Massey D. Social structure, household strategies, and the cumulative causation of migration. Popul Index. 1990;56(1):3–26.

Massey D, Arango J, Hugo G, Kouaouci A, Pellegrino A, Taylor J. Theories of international migration: a review and appraisal. Popul Dev Rev. 1993;19:431–66.

McCann JA, Cornelius W, & Leal D. Engagement in campaigns and elections south of the border pull Mexican immigrants away from US politics? Evidence from the 2006 Mexican expatriate study. Article presented at the Latin American Studies Association Annual Meeting, Montreal; 2007.

Mutz DC. The consequences of cross-cutting networks for political participation. Am J Polit Sci. 2002;46(4):838–55.

Niven D. The mobilization solution? Face-to-face contact and voter turnout in a municipal election. J Polit. 2004;66(3):869–84.

Orozco M, Lowell BL, Bump M, Fedewa R. Transnational engagement, remittances and their relationship to development in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of International Migration at Georgetown University; 2005.

Pérez-Armendáriz C. Do migrants remit democratic beliefs and behaviors? A theory of migrant-led international diffusion. Doctoral Dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin; 2009.

Pérez-Armendáriz C, Crow D. Do migrants remit democracy? International migration, political beliefs, and behavior in Mexico. Comp Polit Stud. 2010;43(1):119–48.

Portes A, Landoldt P. Social capital: promise and pitfalls of its role in development. J Lat Am Stud. 2000;32:529–47.

Pries L. The Disruption of Social and Geographic Space Mexican-US Migration and the Emergence of Transnational Social Spaces. Int Sociol. 2001;16(1):55–74.

Putnam RD. Bowling alone. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2001.

Quintelier E, Stolle D, Harell A. Politics in peer groups: exploring the causal relationship between network diversity and political participation. Polit Res Q. 2012;65(4):868–81.

Smith R. Mexican New York: transnational lives of new immigrants. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2006.

Sniderman P, Brody R, Tetlock P. Reasoning and choice: explorations in political psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

Soehl T, Waldinger R. Making the connection: Latino immigrants and their cross-border ties. Ethn Racial Stud. 2010;33(9):1489–510.

The Americas Barometer by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP); 2008. www.LapopSurveys.org.

Waldinger R. Between “here” and “there”: immigrant cross-border activities and loyalties. Int Migr Rev. 2008;42(1):3–29.

Waldinger RD. A limited engagement: Mexico and its diaspora. The selected works of Roger D. Waldinger; 2009. Available at http://works.bepress.com/roger_waldinger/38.

Waldinger RD, FitzGerald D. Transnationalism in question. Am J Sociol. 2004;109(5):1177–95.

Walzer M. Liberalism and the Art of Separation. Political Theory; 1984;12(3);315–330.

Warnes T. Migration and the course of life. In: Champion A, Fielding T, editors. Migration processes and patterns. London: Belhaven; 1992. p. 174–87.

Weyland KG. Theories of policy diffusion: lessons from Latin American pension reform. World Politics. 2005;57(2):262–295.

Wong R, Palloni A, Soldo BJ. Wealth in middle and old age in Mexico: the role of international migration. Int Migr Rev. 2007;41:127–51.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Katrina Burgess, Covadonga Messeguer, and the anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier drafts, and Francisco Javier Martínez Rodríguez, Eva Rodríguez Rodríguez, Juan Pelcastre, Hilda Hernández, Clara Armendáriz Beltrán, Iván Pérez-Méndez, and Dhariana Gonzalez for their research assistance. I also am indebted to all who participated in interviews.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez-Armendáriz, C. Cross-Border Discussions and Political Behavior in Migrant-Sending Countries. St Comp Int Dev 49, 67–88 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-014-9152-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-014-9152-4