Abstract

Clay feet are heavy and disabling, sadly in the decolonial scholarly battlefield which otherwise requires all-weather feet suitable for ongoing battles. Drawing on autoethnographic experiences in some African universities and drawing on Melanesian cargo cults, this paper argues that to decolonise Africa, African academics should abate cargo cult mentalities which account for pathological and uncritical intellectual dependence on theories, ideas and models from elsewhere. Similarly, drawing on Melanesian bigmanism and drawing on how some academics seek to control how students and colleagues think and write, this paper contends that those that pose as bigmen and bigwomen in African universities are a serious threat to decolonial critical, creative, innovative and original thinking. Thus, populated with some high-ranking academics who, nonetheless, lack decolonial creativity, originality, innovativeness and critical thinking, African universities are – like in Melanesian bigmen societies – marked by patron-client relations within which students and colleagues are sadly corralled into epistemic clientelism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colossuses standing on clay feet is what we academics often become when we engage in captivating academic pageantries each year but fail to innovatively generate vaccines and even original ideas, models and theories relevant to the African continent on which we stage the academic pageantries, yearly. Criticising the late Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe for neck-breaking rates of inflation while ironically failing to notice qualification inflation, status inflation and rank inflation in our universities (Corr, 2021; Bitzer, 2008), we, academics, often fail self-criticism tests. Similarly, criticising the apartheid state for censorship of academics and publications while failing to notice ways in which our own university administrations and fellow academics suppress and repress academic freedom, we, academics, have become colossuses standing on clay feet. Establishing censorship on books, newspapers, establishing textbook approval and adoption processes; censoring academics and preventing them from exercising academic freedom, the apartheid governments in South Africa forced academics, researchers and editors to exercise undue restraint in what they said, taught, published or wrote (de Oliveira et al., 2019; Nishino, 2015). In the apartheid context, editors encouraged authors to exercise restraint when writing books such that innovativeness was compromised; some authors resorted to writing in order to satisfy their publishers who were predominantly white (Kolbe, 2005; Nishino, 2015). Even though the apartheid regime is considered to have collapsed, the problem is that apartheid trained academics not only to conform with its values but also to pass on the apartheid values and practices to students that they teach and supervise, often instrumentally using notes and tricks acquired during apartheid (Bunting, 2006): in this regard, the suppression of academic freedom is reiterable even during the official absence of apartheid since apartheid era notes are reproduceable in the margins of the postapartheid state.

While anthropologists often celebrate the fact that persons are made by society, there is unfortunately hardly any recognition that our personhood, as academics, has been made by apartheid society such that we often continue to reproduce apartheid even after it has been pronounced dead in official parlance. Through banning books, and banning individual academics; through making decisions about academic appointments; through firing academics who were not compliant with apartheid through arresting academics that refused to comply; through deporting academics who were noncompliant; through confiscating passports of academics who refused to comply and through ostracising and disapproving academics who refused to comply; through limiting appointment and promotion prospects of academics who were noncompliant; and through threatening academics with loss of employment if they refused to comply (le Roux, 2018), the apartheid regimes socially constructed the personhood of academics in South African universities. In this regard, some research areas became taboo, as there were pressures which forced academics to select apolitical fields of research which would not attract as much critical scrutiny from the apartheid and colonial regimes.

The Apartheid and Colonial Origins of Clay Feet: Ramifications on the Discipline of Anthropology

Just as the apartheid state sought to keep Black people apart from discourses that could incite rebellion (de Oliveira et al., 2019), academics with vested interests in the past try to keep fellow academics from disruptively reinventing disciplines within universities. Much as intellectual repression was used by the apartheid state against those seen as dangerously unorthodox (le Roux, 2018), intellectual repression is used in universities against those seen as dangerously unorthodox and disruptive in their originality and creativity. Just as academics began to self-censor in order to be able to survive within apartheid (Merrett, 1992), “postapartheid” intellectuals still have to learn to self-censor within universities so as to avoid ostracism and disapproval from fellow academics with stakes in the societal and disciplinary status quo.

Although some thinkers may describe apartheid regimes as thriving on the basis of binaries or dichotomies, this paper argues that apartheid regimes in fact sought to corral and coerce South Africans to collectively live the values of apartheid. Confiscating passports of academics, and assassinating antiapartheid activists like Rick Turner was meant to force academics to collectively consent or acquiesce to apartheid values and practices; similarly, we argue that overstressing and overpolicing old anthropological disciplinary boundaries is reminiscent of apartheid coercion. Besides, when the apartheid regime refused to see Archie Mafeje appointed by the University of Cape Town in 1968 (le Roux, 2018) – even though he was highly qualified and the right candidate for the job – the intention of the apartheid regime was to coerce South Africans to collectively live the values and practices of apartheid which were threatened by the fearless and “disruptive” scholarship of Archie Mafeje. With the official demise of apartheid, South Africans have to deal with universities that have become eager surrogates of the moribund apartheid state – reproducing apartheid values and practices in the supposedly postcolonial and postapartheid society. The complicity of universities in South Africa is well captured by le Roux (2018, p. 464) thus:

But mostly – and perhaps most worryingly when considering the present day – the universities themselves were the agents of suppression. They put pressure on their own academics in a variety of ways: limiting prospects for promotion, threatening them with loss of employment, refusing ethical permission for proposed studies, and censoring them through social disapproval or ostracism. Moreover, academics can limit their own freedom; not all academics have the courage to stand up…

Academic freedom is protected expressly by the “post-apartheid” South African Constitution, (de Vos, 2016; Vaughan & Ncayiyana, 2020; McKenna, 2013), arguably because academic freedom is central to a democracy and because it was foreseen that academic freedom would continue to be trodden upon in the “postapartheid” era: in fact, academic freedom continues to suffer casualties in present day South Africa. Several academics have recently departed from South African institutions of higher learning; and several other academics in the institutions of higher learning have been persecuted and dismissed for decentering systemic structures of apartheid in the postapartheid era. Xolela Mangcu departed from the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), and Ashwin Desai has had trouble from the University of KwaZulu Natal (Habib et al., 2009). Besides, Makgoba was victimised for questioning racist policies and practices at the University of Witwatersrand; in the same vein, Mahmood Mamdani was persecuted by the University of Cape Town for having designed a course outline that challenged apartheid values and the ways in which UCT wanted African studies to be taught “like it was a version of Bantu education,” to use Mamdani’s (1998) phrase. Similarly, Robert Shell, a white American academic based at Rhodes University, was also persecuted and dismissed by Rhodes University for challenging resilient racists practices including nepotistic employment practices, racially based redundancies and non-transformative management practices (Taylor & Taylor, 2010).

In spite of the fact that universities thrive on multiplicity of voices, including the voices of intellectual dissenters who help sharpen ideas; regardless of the fact that ideas are sharpened by a well-balanced education (Habib et al., 2009; Kunene, 2014), and despite the Constitutional protection of academic freedom, academics in South Africa continue to suffer repression, including censorship-postapartheid universities are noted as suppressing academic freedom. Just like the apartheid regime banned African books which they considered subversive, universities are noted as victimising academics who exercise academic freedom in ways that question the universities’ unbecoming modus operandi (Kunene, 2014). The repressive practices of the universities are noted by Habib et al. (2009, pp. 909–910) thus:

What stands out as a telling political feature…is that… even in a post-apartheid society black South Africans (and anyone representing their plight) cannot win when they take on, head-to-head, the entire racialised structure, in today’s former ‘open universities’. As shown, speaking out extracted a high price from all three protagonists (Makgoba, Mamdani and Shell). And however virtuous the exposure of white privilege, mediocrity, and bias might be – it simply does not seem to have enough moral suasion on those most directly implicated to want to make them seek atonement; rather, energy is directed to the normalization of injustice.

Arguing that academics that continue to benefit from the vestiges of apartheid keep on feeling threatened by those that challenge apartheid and its vestiges, this paper also contends that, similarly, such academics feel threatened when their parochialism is challenged by new ideas, new theories and models grounded in African realities. In this regard, the discipline of anthropology is reinventing itself by encompassing competing rationalities, by opening up to new theories; by embracing the nonhuman world; by embracing new materialism, by embracing non-representationalist methodologies; by embracing post-qualitative methodologies; by embracing diffractive methodologies; by creating new modules including quantum anthropology; anthropology of science and technology studies; anthropology of infrastructures; multispecies anthropology; anthropology of architecture; genomic anthropology; molecular anthropology and so on (Biehl & Locke, 2010; Feely, 2020; Vannini, 2019; Kerasovitis, 2020; St. Pierre, 2019; Destrol-Bisol et al., 2010; Palsson, 2008; Ulmer, 2017; Bozalek & Zembylas, 2017). Because novelty challenges traditional ways of doing anthropology, we argue here that some old-guard anthropologists feel threatened when traditional ethnography is challenged by new “disruptive” post-qualitative methodologies; they also feel threatened when traditional ethnography is challenged by new “disruptive” non-representationalist methodologies and they feel petrified when traditional ethnography is challenged by new “disruptive” diffractive methodologies that are emerging. And much as apartheid asserted and policed rigid boundaries, academics that feel threatened by disciplinary reinventions would be seen asserting and policing rigid disciplinary boundaries – including in the discipline of anthropology which is otherwise well known for holism, inclusivity, eclecticism and for periodically reinventing and recreating itself.

Whereas anthropologists are advised to avoid reducing the discipline of anthropology to ethnography, but to use anthropological intellectual tools to speculate on the conditions of human life in this world and to attend to bigger questions and debates beyond ethnography (Ingold, 2014, 2017), old-guard anthropologists may want to continue ethnographizing anthropology notwithstanding ethnographic crises in representing Africans (Noth, 2003; Rudenko, 2017). Whereas anthropologists argue that anthropology is characterised by turbulence, self-examination, inventiveness, and is thus diverse enough to cover topics like biology, geology, natural science zoology, science and technology studies, anthropology of architecture, anthropology of infrastructures and anthropology of biosecurity (de Castro & Goldman, 2012; Ingold, 1997, 2000; Pfaffenberger, 1988; Rabinow, 2003; Schatzberg, 2018; Wentzer & Mattingly, 2018), some traditional anthropologists are tempted to resist the ways in which the discipline is reinventing itself in the twenty-first century. Trained, in apartheid style, to always conceive things in rigid categorisations, some African academics consider the discipline of anthropology in terms of rigid boundaries. Thus, contrary to those that think that the increasingly popular anthropology of science and technology studies is not anthropology, Schatzberg (2018, pp. 203–206) observes the genealogy of the anthropology of science and technology studies thus:

Of all the emerging social-science disciplines in the late 19th century, anthropology seems the most likely discipline to adopt technology as a field in the human sciences. Since its 19th century beginnings, anthropologists have taken artifacts, craft skills, and material culture seriously, although they did not describe these objects of study as technology...technology briefly became a central concept in American anthropology in the 1880s, serving for a time as one of the key subdivisions in American evolutionary anthropology. But technology faded as an anthropological concept by the end of the century. Not until the 1940s did technology return as a key term in anthropology, most prominently in the work of the evolutionary anthropologist Leslie White and Marxist archaeologist Vere Gordon Childe.

What the reactionary and parochial academics in contemporary Africa forget is that many founding fathers of anthropology were not parochial because they had degrees in anthropology, natural sciences including physics, biology and mathematics (Parkin & Ulijaszek, 2007; Sredniawa, 1981; Kroeber, 1935). In fact, Franz Boas had training in physical laboratory sciences and Bronislaw Malinowski had a doctorate in physics and mathematics – with his dissertation situated in the philosophy of science (Sredniawa, 1981; Kroeber, 1935). Besides, whereas some African academics would enjoy setting up rigid distinctions between anthropology and sociology, anthropologists including Radcliffe-Brown (1951); Jain (1986) and Evans-Pritchard (2013) have noted that anthropology is in fact comparative sociology or a branch of sociology which focuses on nonmodern societies. It is this holism and eclecticism of anthropology that makes it particularly well placed to constantly invent and reinvent itself – in fact in the twenty-first century, anthropology is reinventing itself towards what de Castro and Goldman (2012) call a post-social anthropology. In this vein, de Castro and Goldman (2012, p. 435) argue that social/cultural anthropology has arrived at its dead-end such that it needs to reinvent itself. However, circumstances in contemporary African universities reveal that it is far from easy for anthropology to reinvent and recreate itself when academics are possessed by fundamentalist spirits of apartheid which stifle disciplinary reinventions.

Many challenges stand in the way of the reinvention of the discipline of anthropology particularly where the training of graduate students in African universities follows cultic logic with reactionary old-guard supervisors acting like gods and goddesses that would readily punish blasphemous students. Also, afflicted with the impostor syndrome (Marinetto, 2020), new recruits into African universities often want to be told what to publish, where to publish and how to publish – and they feel intensely pressured to banally comply with strictures, even if makeshift. Other challenges standing in the way of the discipline of anthropology reinventing itself include career-oriented self-censorship among African academics who consequently become shallow, narcissistic and opportunistic such that they develop habits of dismissing anything that does not fit their thinking habits or what they narrowly see as the zeitgeist of the discipline. Anything that does not conform to their thinking is pre-emptively trashed by the cults of irrelevance (Lind, 2019). Due to the existence of the cults of irrelevance in African universities, African ministers of higher education have recently bemoaned the failure of African academics to pass the relevance tests (Waruru, 2021): sadly, African taxpayers fund the [irrelevant] researches in African universities with opportunistic academic cults of irrelevance that are obsessed with promotion, even if that is premised on irrelevant and banal publications.

Besides the foregoing, the reinvention of the discipline of anthropology is forestalled by the appointment of incompetent academic administrators some of whom create apartheid era toxic workplaces that disengage staff members from their central duties; thus, for some administrators, blind loyalty is highly valued and highly rewarded over all other traits: this generates sycophantic behaviour, among academics, which is detrimental to institutional and disciplinary reinventions (Hill, 2015; Mohamedbhai, 2015; Wild, 2020); besides, appointments and promotions are often corruptly done in many African universities (Mohamedbhai, 2015; Ssentongo, 2020), resulting in the appointment of incompetent staff with pathetic citations and abbreviated publications to their names. Of course, the idea is not simply to have lots of citations because even publications that are fashionably nonsensical, to use Sokal and Bricmont’s (1998) term, would be cited for the reason of their nonsense and irrelevance. Put differently, a publication that is heavily cited is not necessarily the most relevant to the African context in which it has been written. Citations may show impacts of a publication yet even apartheid had impacts which we cannot celebrate when we are its victims.

In the light of the foregoing, we argue that publications that buttresses apartheid and its vestiges, may be relevant to promotion of the authors but they are not relevant to Africans who struggle to liberate themselves from apartheid and colonialism. Put differently, the kind of originality and creativity that is needed in Africa is one that disrupts apartheid and its colonial vestiges. Publications that do not disrupt apartheid and its colonial vestiges cannot be defined as original and creative because they will simply be still operating within the trite logics of apartheid and colonialism. The point we are making here is that originality must, of necessity, be disruptive and unsettling in the sense of threatening and indeed shaking the very foundations of apartheid and its colonial vestiges. Decolonial anthropology must be uniquely disruptive, it must be different from the old anthropology that was complicit with apartheid and colonialism in Africa. In this regard, it requires the existence of real intellectuals, and not merely the existence of academics, to spearhead decolonisation of the discipline of anthropology. Sadly, as Lange (2013) notes, not every academic working at a university is an intellectual. For Said (1994, p. 22–23) thus:

…the intellectual always stands between loneliness and alignment […] At the bottom, the intellectual…is neither a pacifier nor a consensus-builder, but someone whose whole being is staked on a critical sense, a sense of being unwilling to accept easy formulas or ready-made clichés, or the smooth, ever-so-accommodating confirmation of what the powerful or conventional have to say, and what they do.

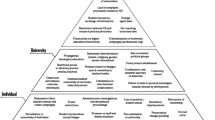

Whereas, on one hand, academics are often happy to be confined into narrow areas of specialisation, intellectuals, on the other hand, would not accept such confinement to narrow areas of specialisation; whereas academics, on one hand, would delight in being professionalised, on the other hand, intellectuals would not accept being professionalised in the sense of being restricted to an area of specialisation which shuts out everything outside the immediate field; whereas academics often celebrate cults of certified experts who sadly confuse credentials with knowledge, intellectuals, on another hand, would detested such cults of certified experts and the credentialism associated with them; whereas academics drift towards authority accepting prescriptions of research agenda or methodologies, intellectuals, in contrast, are loathe to prescriptions of research agendas and prescriptions of methodologies (Lange, 2013). Put succinctly, whereas academics are amenable to cargo cult mentalities, intellectuals are so combative that they even critique the institutional and scholarly bigmen in their midst.

Cargo Cult Mentalities and Bigmanism/Bigwomanism in African Universities

Extremely desirous of foreign cargo including ideas, theories, models and research funding, some African academics have fallen into the trap of cargo cult mentality which is inimical to intellectualism on the continent of Africa. The cargoism that underlies cargo cult mentalities entails a preoccupation with cargo (Lindstrom, 2019), in this case among some academics who do not care to produce their own theories, ideas and models that would be more useful and relevant to Africans. Cargo cult is an anthropological phrase describing Melanesian societies that had grown used to receiving goods, during the Second World War, when American planes and ships landed in Melanesia with cargo – the Melanesians were so disappointed when the war ended as they no longer received the cargo. So, they resorted to making their own makeshift planes using poles and grass; and they also resorted to making their own makeshift airfields in the hope that by so doing they would induce the arrival of cargo. Some of the cargo cults in Melanesia even imitated the sounds of aeroplanes in the hope that aeroplanes would be induced to resume landing with cargo on the island.

Just like the Melanesian cargo cults, some academics delight in patiently and religiously waiting for cargo comprising ideas, theories, models and research funds from overseas: indeed, Melanesian cargo cults waited by their makeshift airfields and by the seaside hoping that cargo would arrive from overseas (Lindstrom, 2019). Similarly, some academics patiently wait in their universities and offices for ideas, theories and models to arrive from overseas. Just like Melanesian cargo cults believe that knowledge is revealed ready-made from the spiritual world, some academics believe that knowledge is revealed ready-made by scholars based overseas. Melanesian cargo cults believe that loyal believers will receive the cargo for which they wait, similarly some academics believe that loyalty and sycophantic behaviour is crucial for the arrival of the cargo from overseas. Just like the cargo cults do not know how the goods are made overseas, some academics do not know how theories, models and original ideas are made overseas; just like cargo cult members believe that some kind of religious rituals (Glines, 1991), including ecstasy, are necessary for cargo to arrive, academics have sadly become ritualists who faithfully believe that cargo will arrive no matter how long Africans have to wait.

Thus, members of the Melanesian cargo cults imitate American soldiers, who used to provide them with cargo during World War 2: the Melanesian cargo cult members fall into ecstasy, while scanning the horizons, the seas and the skies for cargo, as part of their rituals; besides, there are initiations of new cult members; also, the cults drill with wooden rifles, they hold flag-raising ceremonies; the Melanesian cargo cults adopt Western dress and imitate Western behaviour; they wear clothes similar to army uniforms and they behave like military personnel, they built makeshift wharves, storehouses, airfields, “radio-masts” and lookout towers in anticipation of the arrival of good fortune; what is more, cult leaders contact their deities by using “wireless telephones” – often nothing more than wooden posts or carved totem poles. In all this, the cargo cults hope that the planes will soon arrive with cargo; they covet fridges and cars and other cargo which they patiently wait for by the makeshift airstrips and by the seaside (Glines, 1991; Richter, 2011; Tabani, 2013). The Melanesian cargo cultists will not give up: they search the skies, no matter that no cargo has arrived or is likely to do so (Lindstrom, 2004). The point here is that, similarly, in African universities, we, academics, also have been cultured into cargo cult mentalities – always uncritically searching the skies without giving up, in the hope that the cargo of ready-made ideas, models and theories will arrive from overseas.

Of course, like the shamanic priests of the Melanesian cargo cults, the bigmen and bigwomen in African universities expect pious devotion from members of academic cults – in the logics of patron-client relations. Although the term bigmen has also been applied in connection with African authoritarian leaders like Zimbabwe’s late Robert Mugabe (Salafia, 2014), we note that, in universities, there are also authoritarian and dictatorial colossuses on clay feet. Authoritarianism, dictatorship, apartheid and colonialism are not only present in politics but also in the realm of ideas, epistemologies and practices within universities where bigmen and bigwomen rule the days.

The term bigman implies social differentiation within a group; there are big men, there are ordinary men and there are rubbish men – and, around the bigmen, there are followers (Moore, 1998; Rubel & Rosman, 1976); bigmen and bigwomen do not inherit their positions although they are often sons and daughters of bigmen and bigwomen; the bigmen and bigwomen spend most of their time in the inner circle of their followers, who surround them directly; these followers often have their own followers whom they direct when undertaking tasks, these followers transmit commands to the lowest echelons on men and women on the outskirts of the group; the bigmen and bigwomen can make positive or negative recommendations and sanctions; the bigmen and bigwomen’s negative sanctions can lead to suicide; negative sanctions may include levies of fines for quarrelling with another member in the clubhouse or for having failed in some task; sanctions may include expulsion from the group; the bigmen have mystical and supernatural powers because they are custodians of the custodian goblins that crave for blood, and if the bigman/bigwoman fails, the goblin will kill them (Moore, 1998; Rubel & Rosman, 1976).

The point in the foregoing is that some African universities are now populated by cults of academics who like Melanesian cargo cults are given to patient and uncritical mimicry of whatever they receive from overseas (Nyamnjoh, 2004). They envy not only ideas, theories and models from overseas but they like Melanesian cargo cults, they envy fridges, funds and cars from overseas. Lacking originality, creativity and innovations of their own, they have become pious ritualists always casting eyes to the skies and to the seas hoping for the arrival of cargoes of various kinds. We argue that reducing the originally critical disciplines like sociology, anthropology and philosophy to mechanical handbook style applications, some senior academics in Africa have sadly assumed bigmen/bigwomen missionary logics in universities – blocking university corridors and offices for those that refuse to be uncritically converted to certain models, ideas, theories and other cargo. Forgetting that even disruptive technologies are being celebrated, in the twenty-first century, as innovative; some academics are so pious to foreign theories, ideas and models which they have learnt in school that they are averse to any new ideas that appear to be, or are indeed, disruptive of conventional ideas, theories and models.

Of course, new ideas are necessarily disruptive not only to old ideas, theories and models but also to the careers of those that are disciples of the old establishments, ideas, models and theories. Whereas universities, typically those in the Global North, encourage and promote critical thinking and even disruptive thinking, some universities in Africa have got phobias for critical and disruptive thinking. No wonder why many postgraduate theses in Africa are often characterised by mere descriptivism that does not push boundaries of the disciplines within the African universities. With rank inflation obtaining in many universities in Africa where, often, many are promoted to professorship on the basis of descriptivist and abbreviated publications – with some papers even ranging from 1 to 4 pages long and citations pathetically counting below a hundred or about a hundred in total – it is no wonder why creative, innovative and disruptive thinking are increasingly becoming unpopular particularly among those academics whose ranks are inflated. Whereas universities like the University College London (UCL) (2022) test their undergraduate students for creative, innovative and disruptive thinking, in Africa, students and fellow academics get punished or scorned and scoffed at for thinking disruptively. Thus, the University College London (2022) writes: “Thinking disruptively has been the status quo for UCL since 1826…to keep us pushing the frontiers of new disciplines, new knowledge, and new ways of relating with the world we live in.”

Staffed with some ritualistic academics bearing inflated ranks but with very small ideas, for want of disruptiveness, it is no wonder that African universities have failed not only to produce theories and models relevant to the African situations: African universities have also failed to produce vaccines for COVID-19 on the continent. In the logics of COVID-19 vaccine “fill and finish” processes that Europe and America are currently promoting on the African continent, this paper argues that African academics have similarly reduced themselves to fill and finish academics who thus wait patiently for theories and models to be produced from Europe and America and then their duties would be to simply fill and finish the theories by adding African data to validate the theories which they then uncritically apply to African societies. In this regard, fill and finish academics are slavish in the sense of delighting in being uncritical handymen/women of overseas scholars who originate the theories, models and disruptive ideas which are subsequently applied by the slavish academic handymen/women in Africa. In short, handymen/women’s mentalities, also associated with cargo cult mimicry, have reduced African universities to cultic logics where disruptive thinking, in an Afrocentric sense, has become anathema. In contrast to what is obtaining in African universities, Spence (2021), who recently became president and provost of the University College London, writes:

The political philosopher Ronald Dworking once described the university as a theatre for the exercise of the independence of the mind, a place where individuals are free from unnecessary interference in the pursuit of their understanding of “truth”. In a healthy university, academics and students would be fighting for causes they think are right and, where relevant, debunking ideas that they believe are wrong.

Dereliction of duty is the description suitable for universities and academics who become slavish ritualists delighting in the fill and finish logics involving the uncritical application of theories and models from overseas. Underlying such dereliction of duty is the virus of mimicry that has infected some African academics (Nhemachena, 2021), who would naturally need sanitisers to restore the vitality of African institutions of higher learning. If African universities are infected by viruses of ritualistic mimicry, one wonders what community service such universities and academics offer, to African communities, other than infecting them with similar contagious viruses of mimicry. If African universities are populated by “professors” who are so afraid of hearing their own voices that they cry “disruptive” each time they hear their own African voices, one wonders what community service is offered by such “professors” other than teaching African communities to develop phobia for themselves and for their own voices. If African universities are populated by “professors” who are so much afraid of their own autonomy and sovereignty, one wonders what community service is being offered in Africa other than Afropessimism. Similarly, if African universities are populated by “professors” who are so afraid of their own autonomous ideas that they excessively compulsively seek approval and kudos from former colonisers in order to publish about Africa, one wonders what community service is offered by such academics other than pathological excessive compulsive behaviours that defy autonomy. Put differently, whereas self-confidence and self-assertiveness are part of what is needed to decolonise Africa, “professors” who lack confidence in their own voices and publications as Africans constitute a dereliction of duty because they instil diffidence among African communities which they ironically claim to provide with community service.

African community members give their voices or words to the “professors” in research and the “professors” uncritically use Western models and theories to “interpret” the African voices and words – and of course they submit the journal articles which are products of such research to Eurocentric journals for approval and kudos. Put differently, “professors” with clay feet cannot be confident about anything African, not because there is nothing to be confident about in Africa but due to their own clay feet which are slippery, and hence not reliable and suitable for all, including disruptive, terrains in an intellectual sense. If adventurers need all-terrain vehicles to manoeuvre, African academics need all terrain-feet if they are to disruptively and creatively follow through ideas and theories in the intellectual adventurers – feet of clay are not good enough for intellectual adventures though they may be good for cargo cults that wait for cargo by the seaside and by the makeshift airstrips.

Much as someone with clay feet cannot easily walk far and over long distances, academics with clay feet may not be able to intellectually imagine matters that may be far into the future: all they can cognise is what is cognitively proximate. Disciplines are understood by such academics solely in terms of presentism and never in terms of how they can be improved in the future: such academics lack imagination beyond the present tense of the disciplines. In other words, much as clay is inelastic, our minds are often so inelastic that we are disabled to imagine developments in our own disciplines: we fail to stretch our minds to realise that disciplines are continuously developing, since their inception. Indeed, universities themselves are in continuous processes of becoming, since their inception. One may want to consider the discipline of anthropology originally designed to study the “primitive other,” the “savage other,” the “barbaric other,” and to study the small local scale societies. In this regard, anthropology as a discipline has had to reinvent itself many times because of the disappearance of isolated societies, small scale societies and local societies; anthropology has had to reinvent itself because of the disappearance or nonexistence of the supposed object – “the primitive other,” “the savage other” or “the barbaric other.” Along with changes in the discipline of anthropology, its methodologies are also changing and there are projections of further changes and reinventions in the future of the discipline of anthropology and its methodologies.

The upshot of the foregoing is that if we, as academics, are proud of our clay feet, we will not be able to follow the developments or becomings of our disciplines; we will be given to dismissing any reinventions and redefinitions of the discipline as not anthropology or not methodologically anthropological. Sound academics are the ones that are abreast with the contemporary developments in their disciplines such as anthropology: academics with clay feet cannot, by definition, be sound because, like prophets facing backwards – to use Meera Nanda’s (2003) phrase – they tend to pull the discipline backwards, sticking as they would do to traditional definitions of anthropology and its methodology. Understandably, of course, clay feet are heavy feet which make it difficult to track, in real time, contemporary and future developments in the discipline of anthropology and its methodologies. Real professors are not only creative, original and innovative but they are also disruptive: yet these professorial qualities are summarily dismissed by some academics in some universities on the continent of Africa. In fact, one of the reasons why professors are given security of tenure is for them to be fearlessly disruptive in their thinking. Real professors push the boundaries of the discipline of anthropology and its methodologies. In this regard, much as Africa is currently destroying stale COVID-19 vaccines, academics in Africa should understand that the discipline of anthropology reinvents itself so that it does not become stale enough to warrant extinction. For this reason, anthropologists must appreciate those among their ranks who are disruptive, because imperatives of anthropological reinvention necessarily entail disruption of conventions in the discipline and in the broader society.

Anthropology and the Instantiations of the Melanesian Cargo Cult Mentalities: a Self-experience

Having noted the foregoing, we now want to draw on our own experiences in African universities where we have not only seen some supervisors force-feeding postgraduate supervisees with their own theoretical, methodological, and even title preferences for research – sometimes even selecting readings and debarring supervisees from reading as freely and widely as they want around their topics of study. We have also seen such bigmen-like and bigwomen-like academics trying to coerce colleagues to pursue life preferences similar to or the same as their own: when they buy a particular kind of car for a particular price, they expect and indeed would subtly coerce colleagues to do the same. In fact, some two colleagues at one university mocked each other because one of them had a smaller car such that when the other waved at him by way of greetings, on the road, the one with a smaller car could, as stated later, supposedly not be seen by the one with a bigger car, ostensibly because the one with a bigger car was loftier. Of course, as academics, one would have expected them to spend more of their time and pride discussing how to generate big intellectual ideas, if they had any such ideas at all, rather than wasting time boasting about the sizes of their cars. Besides, some academics are so preoccupied with one another’s heights that instead of spending time meditating over ideas and intellectual matters in the universities, they waste time casually comparing the heights of fellow academics. Similarly, when some academics buy particular types of houses for particular prices in particular suburbs, they would expect and even subtly coerce colleagues to do the same. Surprisingly, such academics would frequently, even incessantly, give excuses for not attending academic seminars to present and discuss ideas – and of course they would resist any attempts to force them to attend the seminars. If African universities are populated by such academics, one wonders about the fate of academic freedom when we have academics who are as officious as to infringe even in the personal and non-academic matters of colleagues. The point is that some academics criticise state leaders for suppressing or infringing freedoms of speech, freedoms of expression and individual freedoms, even as they are infringing on academic freedoms of colleagues.

Besides, when such academics buy particular types of neck ties, they expect, and indeed they subtly coerce, colleagues to do the same; when they attend certain kinds of churches in particular localities, they would expect, and indeed subtly coerce, colleagues to do the same; when they have studied certain programmes at certain universities, then they would subtly mock colleagues who studied different programmes at different universities. If academics subtly coerce others over such mundane matters, one wonders whether such academics would yield academic freedom where it matters. If academics in African universities are more worried about such mundane matters, and not as much about ideas and intellectualism, it is cause for concern whether they would be able to keep abreast with contemporary developments in their disciplines, and in related disciplines with which disciplinary boundaries are shared. The point here is that while academics fetishise cars, neck ties, degree certificates, houses and narrow disciplinarism, intellectuals on the other hand do not fetishise anything because for an intellectual, there are no sacred cows beyond disruptivity. Intellectuals do not readily accept ready-made formulas and taken for granted conventions – they seek to go far in pursuit of ideas as food for thoughts.

While anthropology is famous for being self-critical as a discipline, for being reflexive, for being holistic, for being sensitive to change and differences, one of us was shocked several years ago when he was invited for an interview, at one of the smallest universities in South Africa, which turned out not to be an interview but a police-like interrogation about his scholarly originality, disruptive and independent thinking. The panel of interrogators was apprehensive of the invitee’s prolific and “disruptive” publications on decoloniality such that one of the panellists even queried him, without compliments, about how he manages to be so prolific. The invitee was called into a room wherein panellists were sitting and already looking sullen. Upon entry, there were introductions wherein areas of research interest were also stated. The invitee introduced himself and stated his areas of research interest, as well, including the anthropology of science and technology studies. In spite of not having any training in anthropology or even sociology, one of the male panellists immediately quibbled that anthropology of science and technology studies was not anthropology because it had to do with science and technology. Alas! As if that was not enough, he unashamedly pointed at one ICT academic in the room and said “technology is that one.” The invitee was shocked but did not respond immediately, choosing as he did to wait for the actual interview to begin. Then the invitee was asked to do a short presentation. After the presentation, questions followed which were answered very well but incidentally the invitee mentioned decoloniality during one of the responses and this caused pandemonium in the room, turning the interview into an interrogation. The invitee was asked by the sullen chairperson of the panel of interviewers as to where decoloniality was coming from.

At first, thinking that it was an honest and well-meaning question from the chairperson, the invitee responded to say decoloniality comes from African experiences with colonialism and from scholarship, including the works of luminaries like Ngugi wa Thiong’o (1986) who wrote about decolonising the mind; Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2013, 2016) who also writes about decoloniality from an African perspective; Franz Fanon (1967) and some scholars, from Latin America, including Maldonado-Torres (2008), Grosfoguel (2011) and others. Then the chairperson of the panel stood up, swearing that she would not give the invitee the job because of his leanings towards decoloniality and stating that his presentation had been “very solid” but that the mention of decoloniality was detestable and horrible. The chairperson then said to the invitee, “Having been educated at the University of Cape Town, we expected you to know what we want, not this decoloniality.” One panellist who had come all the way from the University of Cape Town then asked whether anthropology is colonial, to which the invitee responded in the affirmative, citing sources and providing evidence from the South African context. The inquirer got further infuriated and then reminded the invitee that he had been provided with a scholarship for his PhD studies [in anthropology] at the University of Cape Town after all. It was clear that with the chairperson of the panel having been infuriated by the mention of decoloniality, the other junior members of the panel similarly became even more hostile, understandably to please their boss who was chairing the interrogation, with some impatiently asking questions even as the invitee was in the middle of answering previous questions by other panellists. Of course, when the chairperson of the panel swore that she wanted to give the invitee the job but for his inclinations to decoloniality, the invitee wondered about the necessity of continuing to sit in the room when the verdict had already been announced – why continue sitting down and answering any more questions.

It is well documented that luminary scholars like Archie Mafeje were ostracised including by their alma maters, like the University of Cape Town which, for instance in 1993, after apartheid had formally ended, continued to scoff at him; and indeed, the university offered him a job as a Senior Research Fellow, with a salary pegged at Senior Lecturer level regardless of the fact that Mafeje already had 20 years at the level of a Professor at renowned universities around the world (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2016). Also, when the distinguished scholar, Walter Rodney, was assassinated, using a bomb that was placed in his car, authorities of Guyana humiliated him posthumously by writing on his death certificate that he was unemployed when in fact he had been a Professor prior to his death (Jamaica Observer, 2021). Similar experiences are found in countries like Zimbabwe where some academics were banned from teaching at state universities because they criticised state leaders, including the late Robert Mugabe.

Thoroughly infuriated by the mere mention of decoloniality, the chairperson of the panel ceased to appropriately moderate the proceedings, and all she kept on declaring repeatedly was, “I wanted to give you this job but I do not want your decoloniality stuff. Why do you not just focus on postcolonial theory instead of decoloniality?” As if not wanting to be left out, the male panellist who had first commented on the anthropology of science and technology studies further remarked impatiently, “what you are saying is disruptive.” And then, without waiting for the invitee to respond to the previous comment, a lady panellist asked whether the invitee would want to teach anthropology of science and technology studies, to which the invitee responded in the affirmative. Then, without asking for justification from the invitee, the lady panellist then ruled that the anthropology of science and technology studies was not anthropology, apparently because it was about technology and not about culture and society of “primitive” people. The unfortunate thing is that when African academics still think that ordinary Africans are primitive, by extension they regard African universities and publishers to be primitive as well. The grammar of primitivism still afflicts some African academics in the twenty-first century.

Gauging the mood of the interrogation and being acutely aware of how other scholars including Archie Mafeje, Mahmood Mamdani (see Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2016; Mamdani, 1998), George James, Walter Rodney (Jamaica Observer, 2021; Johnson, 2015; Edmonds, 2014; James, 2009; Mohammed, 2016) and many others had been sanctioned, ostracised, dismissed and even, some were, assassinated because of their unmatched creative geniuses, originality, fearless autonomy and academic freedom, the invitee wondered why he continued sitting in the room with the panellists. In fact, the chairperson of the panel had already mentioned the University of Cape Town when she reminded the invitee that having studied at the University of Cape Town he should have known what the panellists wanted – which is not decoloniality. The invitee had to find a diplomatic way to have the interrogation stopped as soon as possible. The invitee had to offer apologies about the kind of anthropology he was interested in. When one meets walls of ignorance all around, it is often prudent to plead ignorance so that opponents can happily emerge from their trenches and life can go on. The point is, when ignorance is omnipresent, one can only defeat such ignorance, not necessarily by opposing it, by pleading ignorance as well – this has the cathartic effect of mollifying ignorance.

It being better to develop cold feet than to have clay feet, the invitee subtly intimated to the panellists that he would rather teach in another related discipline like sociology than to teach a particular kind of anthropology that would be foisted on him. It was evident from the interrogations that panellists had their own version of anthropology, or something worse, which they were keen to foist. Of course, the invitee had already concluded in his mind that this was not the type of university he would want to work in since such a university did not value academic freedom and would, thus, be similar to an [academic] prison where the mind gets arrested and stunted. The university was far from intellectually stimulating, with academics being told what to say and what to think including by administrators who evidently prefer postcolonial theory over decolonial theories – and would want academics to cultishly follow their preferences. Apart from risks to one’s physical security, in an environment where people are so rancorously emotional about one’s thoughts and ideas, such universities would be a threat for intellectual growth and academic freedom. The absence of academic freedom could be one of the reasons why the panel members were ignorant about contemporary developments in the discipline of anthropology and in the methodologies that are used in anthropology.

Whereas scholars like Latour (2005); Rabinow (1996, 2016); Rabinow and Bennett (2009); Pfaffenberger (1988); Ingold (1997, 2000); De la Cadena et al. (2015); Pyyhtinen and Tamminen (2011); Krautwurst (2014) and others have published a lot on the anthropology of science and technology studies, panellists were ignorant of such shifts in the boundaries of the discipline of anthropology, and the methodologies associated with the discipline. When there is no academic freedom, academics lose the steam to read and publish meaningful papers and books – they may quietly publish any claptrap just to get promotion and feed their family. Put succinctly, academics in such universities begin to savour pageantries about their ranks and titles, and they forget about ideas that matter in intellectualism.

Intellectualism is a casualty in the absence of academic freedom within universities. When intellectualism dies, the risk is that academics become ritualists in the order of Melanesian cargo cultists – given to religiously following orders like zealous converts. Of course, such ritualist behaviour is unhelpful to African communities and taxpayers who guarantee the pay checks of such ritualist academics. Scandalously, such academics become mercenaries interested more in material perquisites of their offices than in benefiting the African communities from whom their pay checks come. Put differently, African universities are increasingly becoming populated with what we call academics of fortune, in the order of soldiers of fortune, that secure ritualist positions in universities in the hope of getting fortunes, and in all this they are tempted to use all tricks to occupy inflated positions and titles for which they may not be worth in real term.

Back to the experiences, having already published a lot around decoloniality and in the anthropology of science and technology studies, the invitee wondered how working for that particular university, that had invited him, would ever assist him in any way to grow a free mind determined to free other African minds. Bearing in mind the low remuneration in many African universities, and bearing in mind the fact that what actually motivates some intellectuals, including the invitee, is not mainly remuneration but the academic freedom to research, write and publish freely; the interrogation ended at a time when the invitee had already concluded in his mind that even if offered a job by such a university, it would not be worth it in real scholarly and intellectual senses. It would be detrimental to his intellectualism and a big blow to academic freedom as he would be forced to worship a cult of academics without the freedom to even choose his own theory to use or apply in his publications and without even the latitude to research, write and publish in ways that would push the boundaries of the discipline of anthropology. In the interrogation [of the invitee], anthropology was assumed, without question, to be cast in stone with rigid disciplinary boundaries within which theories and methodologies preferred by certain members of the panel would have to be applied with the devotion and religiosity of a member of a cult. To the invitee, it was like being asked to become a vegetable in a university, and to stop dreaming intellectually, but to only live someone else’s dreams.

Of course, the chairperson’s declarations that she wanted to give the invitee the job but for his leanings towards decoloniality, she couldn’t, were not only pathetic but amounted to subtle attempts to justify inhibition of the freedom to think: it amounted to mockery of the value of the freedom to think. In other words, it amounted to a denkverbot – a prohibition to think, and it presupposed that all academics are so unprincipled that they can readily forgo their academic freedom, their freedom to think, write and publish merely for the material perquisites of being an academic. If a dog would think as its owner wants it to, simply because it is getting material perquisites from the owner, what difference would it be for an academic who abandons free thought and academic freedom simply because of considerations of material perquisites of being an academic? Put simply, if academics are not motivated more by academic freedom to think, research, write and publish innovative, original, creative and even disruptive ideas, then it is difficult to imagine what distinguishes academics from animals which are concerned merely about immediate material means of survival for the day. Not to dismiss the necessity of material perquisites of being an academic, anyway, there is no university that would be able to really and sufficiently compensate for the levels of education of an academic – academics are consistently underpaid materially and so many of them retain their jobs more for the love of academic freedom than for the material perquisites. Indeed, they may even be paid more in the private sectors or in consultancy institutions than in the universities: the only major advantage for universities is the ideal of a space for academic freedom, which unfortunately suffers when universities are invaded or infected by bigmanship and bigwomanship as well as by cargo cult mentalities that stifle academic freedom and thus disincentivise academic work.

Being a discipline that is holistic, reflexive and sensitive to the dynamism and fluxes of quotidian life, anthropology is understandably one of the most versatile disciplines covering linguistic anthropology, historical anthropology, biological anthropology, medical anthropology, political anthropology, economic anthropology, socio-cultural anthropology, archaeological anthropology, physical anthropology, anthropology of materialities, anthropology of infrastructures, architectural anthropology, anthropology of the environment, quantum anthropology, genomic anthropology, molecular anthropology, cognitive anthropology/psychological anthropology, anthropology of science and technology studies etc. Being versatile and diverse, as it is, there may well be some academics who are not as versatile as the discipline in which they are lodging. In this regard, such parochial academics must not dismiss what they do not know as “not anthropology” simply because they themselves are not aware of all the subdisciplines and branches of anthropology – both emergent and established. In any case, the boundaries of the discipline of anthropology, like all other disciplines, are fast changing and scholars are always pushing the boundaries of their disciplines via innovative, original, creative and disruptive thinking, writing and publications. Those disciplines with academics who are conservative and lazy to stretch their minds beyond what they themselves studied at college suffer stagnation.

In fact, real theses, such as the theses that we, as academics, expect our PhD students to write should necessarily be original, creative and disruptive to existing knowledge – if they are not original, creative, innovative and disruptive, then they are not theses in the real sense of the word thesis, and thus will not have to be passed. It then baffles the mind to meet academics who are so aversive to creativity, originality and the attendant disruption such that they whimper when original, creative, innovative and disruptive thinking begins to take place in their presence or in their scholarly neighbourhoods. In fact, during our student years, we used to warn the weak-kneed ones that academic blasting was taking place in our rooms of residence and so the weak-kneed and faint-hearted ones were forewarned to stay away. Perhaps real intellectuals in Africa should similarly always warn the weak-kneed and faint-hearted academics to stay away when academic blasting is about to take place. That way the faint-hearted and weak-kneed ones will not be disrupted by academic blasting – after all if the weak-kneed academics have clay feet, they would not be able to run away from disruptive academic blasting once it begins to take place in their presence.

Contrary to the panellists’ assumptions, the anthropology of science and technology studies is already being taught in anthropology departments in many American and European universities and colleges including Yale University, Stanford University, George Washington University, Harvey Mudd College, York University, University of California, Berkeley and many others. Piqued by the amount of ignorance that the panellists showed during the interrogation, the invitee subsequently downloaded one course outline for anthropology of science and technology studies at Yale University, in America, and shared it with the nonanthropologist panellist who had claimed, during the interrogation, that anthropology of science and technology studies was not anthropology. The former panellist then responded to say he had shared the email with the anthropology department at his university and he expressed his interest in beginning to collaborate with the invitee. Sadly, he has once again not made his promise good and that is one reason why, in the interest of the reinvention of the discipline of anthropology in Africa, we decided to write this paper hoping that it would enrich him and his fellow panellists – in the absence of the promised collaboration.

The problem with some African academics is that they assume that anthropology is a static and lifeless discipline even as anthropologists across the world are writing about animism, vitalism, entanglements, networks, meshworks, affectivity, assemblages and so on (Baker & McGuirk, 2017; Latour, 2005). A vital and live discipline such as anthropology would naturally grow and develop, reposition and reinvent itself in such a way that its substantive and methodological boundaries are constantly shifting, labile and being redefined. Not every shift in boundaries and not every redefinition of boundaries is reducible to interdisciplinarity – and of course versatility and holism which have historically characterised the discipline of anthropology do not amount to interdisciplinarity. Thus, writing about new relational anthropology, Welz (2021, pp. 44–45) argues:

Inquiring into European ethnology’s scope in the 21st century allows us to reflect on the divergent disciplinary developments that make up the academic landscape of global anthropologies. Anthropologies, then, are not a universal endeavour. Rather, they represent a number of historical projects…Debates about the Anthropocene challenge anthropology – anthropology understood as a disciplinary ethnology – to reposition itself not only vis-à-vis other disciplines in the sciences and humanities, but in a more general way, as a knowledge-making enterprise…This enterprise is being called upon not only to be able to explain how the present emerged from the past. Rather, we are increasingly also called upon to develop prognostic skills and forecast possible futures for humanity.

Besides, the concern with disciplinary and epistemological boundaries which is presupposed in interdisciplinarity is otiose in a context where anthropology and sociology have taken an ontological turn within which they are being redefined. In fact, scholars such as Latour (2005) are redefining sociology not in terms of society but in terms of associations – and anthropology itself is being redefined in terms of the postanthropocentric turn and new materialist turn. In this regard, the postanthropocentric turn implies that the Anthropos in anthropology is no longer the central or privileged concern. And of course, the ontological turn and the postanthropocentric turn have methodological consequences for traditional anthropology within which some African academics may still be stuck. Ethnography itself is being rethought away from the anthropocentrism and representationalism that it historically presupposed. With the emergence of relationality and the affective turn in anthropology, including relational anthropology (Desmond, 2014; Rutherford, 2016; Welz, 2021), substantive entities, including the Anthropos, are losing the kind of centrality that they were accorded in traditional anthropology. In this sense, Law (2004) has published an interesting book entitled “After Method: Mess in Social Science Research.” The point we are making here is that it is fatal, and indeed counterproductive for academics in Africa to assume that disciplines are static, and to assume that disciplines are all what they personally know and that what they do not know or never studied at college is not part of the discipline.

The point in the above is that some academics mistake the limits of their minds with the limits of the discipline of anthropology. If anthropologists study rituals of renewal in various societies, the question is why some academics assume that the discipline of anthropology is static and should not renew itself? And of course, to assume that one knows all there is to the discipline of anthropology is to be again unanthropological: no wonder why the great philosopher Socrates (Austin, 1987) argued that those who know that they do not know are the ones who really know, and those who claim to know are the real ignoramuses who are not even aware of their own ignorance. In the same token, the logic of the discipline of anthropology has for long been for its practitioners to learn from interlocutors and participants of different societies: real anthropologists do not assume that they know it all. Rather, they assume their own ignorance in order to be able to learn from others, including interlocutors and participants in the so-called primitive societies. In the same vein, the fact that one is a panellist does not mean that one knows the discipline better than the one who has been invited before the panel.

The problem is that some [African] academics, afflicted by cargo cult mentalities of the Melanesian order, assume that what they have received during their student years is all that there is to anthropology. And, they continue to patiently wait for new cargo to arrive again, from elsewhere outside the continent of Africa, without critically engaging with matters of the day in order to produce their own ideas in a continent that has remained lingering and longing for a decolonial turn for a long time now. In other words, they do not seek to innovatively and disruptively produce for themselves but they wait for cargo from elsewhere. It is sad to note that anything new that is created on the continent of Africa is summarily dismissed as supposedly disruptive, and as not what it is. By extension, such cargo cult mentalities explain why afflicted academics would even be tempted to dump their own babies that are supposedly disruptive simply because they are African babies. The point, here, is Africans afflicted with cargo cult mentalities would similarly be tempted to dump their own spouses and look for spouses from elsewhere outside the continent; similarly, such afflicted Africans would be tempted to dump their own African education and look for education elsewhere; in the same vein, the afflicted Africans would always dump African publications and look for books published elsewhere outside the continent; they would even uncritically dump African publishers and look for publishers elsewhere outside the continent. As Stone (2018) argues, the idea for African anthropologists should be to strategically aim to reconstruct, redirect and combatively recentre African subjects as sovereign entities, and to develop African consciousness in which the solid structure of African consciousness, intention and expectation are centred.

Contrary to African-centredness, cargo cults are demonic in nature: afflicted Africans get possessed by what Mawere (2021) calls “a demon of xenophilia” – that is, love and hunger for foreign things even if the things work to their disadvantage and that of their people. The million-dollar question here is whether African academics afflicted by the cargo cult mentalities would be, as part of their community service, be able to effectively advise societies around them to refrain from African baby dumping – the point is, such academics with cargo cult mentalities are also dumping everything disruptively African.

Conclusion

Being the ghostly feet of the captive past, clay feet promise to African anthropology bountiful intellectual deadwood that will pull Africans forever into slavishness and sluggishness. If African academics continue to bury their heads in the sand and ignore the reality of the processual nature, including revolutions, of the world around them, then the discipline of anthropology will run into extinction: if species survive by creatively adapting to their environments, the question is why the discipline of anthropology must be defined and maintained as static and unchanging? Much as markets are marked by creative disruption and creative destructions which generate innovations, disciplines such as anthropology also survive extinctions via instantiating creative disruption and creative self-destruction. In any case, new things are born out of destruction of the old ones. When anthropology becomes moribund, even clay-footed nonanthropologists begin to want to dictate the supposed canons of the discipline. In any case, it is trite that the dead have to have someone else, including from outside the disciplinary tribe, to speak for them. Put succinctly, when clay-footed nonanthropologists begin to speak for the discipline of anthropology, this is a sure sign of the death of the discipline of anthropology. Africa cannot afford professors who enjoy burying their heads in the hot sands of the tropics: it is simply too costly for intellectual progress on a continent that has already suffered, for long, the travails of cargo cult mentalities.

References

Austin, S. (1987). The paradox of Socratic ignorance (how to know that you don’t know). Philosophical Topics, 15(2), 23–34.

Baker, T., & McGuirk, P. M. (2017). Assemblage thinking as methodology: Commitments and practice for critical policy research. Territory, Politics, Governance, 5(4), 425–442.

Biehl, J., & Locke, P. (2010). Deleuze and the anthropology of becoming. Current Anthropology, 51(3), 317–351.

Bitzer, E. M. (2008). The professoriate in South Africa: potentially risking status inflation. South African Journal of Higher Education, 22(2), 265–281.

Bozalek, V., & Zembylas, M. (2017). Diffraction or reflection? Sketching the contours of two methodologies in educational research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(2), 111–127.

Bunting, I. (2006). The higher education landscape under apartheid. In N. Cloete, et al. (Eds.), Transformation in higher education. Higher Education Dynamics (Vol. 10). Dodrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-4006-7_3

Corr, J. (2021). University professorships are subject to grade inflation. The Times. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/university-professorships-are-subject-to-grade-inflation. Accessed 25 March 2022.

De Castro, E. V., & Goldman, M. (2012). Introduction to post-social anthropology: Networks, multiplicities, and symmetrizations. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 2(1), 421–433.

De la Cadena, M., Lien, M. E., Blaser, M., et al. (2015). Anthropology and STS: Generative interfaces, multiple locations. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 5(1), 437–475.

De Oliveira, M. F., Moraes, M. P. A., et al. (2019). South African censorship: The production & liberation of waiting for the barbarians. Acta Scientiarum: Language and Culture, 41(2), e45604.

De Vos, P. (2016). Pierre de Vos: Academic freedom and the constitution: Experiences from post-apartheid South Africa. Forum for Science and Democracy. https://www.uib.no/en/rg/vitdem/100412/pierre-de-vos-acadmic-freedom-and-constitution-experiences-post-apartheid-south. Accessed 25 March 2022.

Desmond, M. (2014). Relational ethnography. Theory and Society, 43, 547–579.

Destrol-Bisol, G., Jobling, M. A., et al. (2010). Molecular anthropology in the genomic era. Journal of Anthropological Sciences, 88, 93–112.

Edmonds, K. (2014). After 34 years, Walter Rodney’s assassination in Guyana now under review. https://ncla.org/blog/2014/5/7/after-34-years-walter-rodneys-assasination-guyana-now-undr-review. Accessed 26 March 2022.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (2013). Social anthropology. Routledge.

Fanon, F. (1967). A dying colonialism. Grove Press.

Feely, M. (2020). Assemblage analysis: An experimental new-materialist method for analysing narrative data. Qualitative Research, 20(2), 174–193.

Glines, C. V. (1991). The cargo cults. https://www.airforcemag.com/article/019/cargo/. Accessed 15 March 2022.

Grosfoguel, R. (2011). Decolonising post-colonial studies and paradigms of political economy: Transmodernity, decolonial thinking, and global coloniality. Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World, 1(1).

Habib, A., Marrow, S., & Bentely, K. (2009). Academic freedom, institutional autonomy and the corporatised university in contemporary South Africa. Social Dynamics, 34(2), 140–155.

Hill, R. (2015). The peter principle is alive and well in higher education. https://evollution.com/managing-institutional/higer-ed. Accessed 21 March 2022.

Ingold, T. (1997). Eight themes in the anthropology of technology. Social Analysis, 41(1), 106–138.

Ingold, T. (2000). The perception of the environment: Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill. Routledge.

Ingold, T. (2014). That’s enough about ethnography! HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 4(1), 383–395.

Ingold, T. (2017). Anthropology contra ethnography. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 7(1), 21–26.

Jain, R. K. (1986). Social Anthropology of India: Theory and Method, in Survey of Research in Sociology and Social Anthropology. New Delhi: Indian Council of Social Science Research.

Jamaica Observer. (2021). Guyana Gov’t to formally recognise Dr Walter Rodney. https://www.jamaicaobserver.com/latestnews/Guyana_govt_to_formally_recognise_Dr_Walter_Rodney. Accessed 27 March 2022.

James, G. G. M. (2009) Stolen legacy: Greek philosophy is stolen Egyptian philosophy. The Journal of Pan African Studies 2009 eBook.

Johnson, C. D. (2015). An investigation into the death of Professor George G. M. James. https://medium.com/@afrdiaspora/an-investigation-in-the-death-of-professor-george-g-m-james. Accessed 10 March 2022.

Kerasovitis, K. (2020). Post qualitative research – Reality through the antihierarchical assemblage of non-calculation. Qualitative Report, 25(13), 56–70.

Kolbe, H. R. (2005). The South African print media: From apartheid to transformation. School of Journalism and Creative Writing, University of Wollongong PhD thesis.

Krautwurst, U. (2014). Culturing bioscience: A case study in the anthropology of science. University of Toronto Press.

Kroeber, A. L. (1935). History and science in anthropology. American Anthropologist, 37(4), 539–569.

Kunene, D. P. (2014). Ideas under arrest: Censorship in South Africa. Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 38(1), 219–238.

Lange, L. (2013). Academic freedom: Revisiting the debate. Council of Higher Education (CHE) (pp. 57–75). Pretoria: Inxon Printing & Design.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor network theory. Oxford University Press.

Law, J. (2004). After method: Mess in social science research. London & New York: Routledge.

Le Roux, B. (2018). Repressive tolerance in a political context: Academic freedom in apartheid South Africa. History of Education Quarterly, 58(3), 462–466.

Lind, M. (2019). Are academics pursuing a cult of the irrelevant? The National Interest. https://nationalinterest.org/feature/are-academics-purusing-cult-irrelevant. Accessed 13 March 2022.

Lindstrom, L. (2004). Cargo cult at the third millennium. In H. Jebens (Ed.), Cargo, cult and culture critique. University of Hawaii Press.

Lindstrom, L. (2019). Strange stories of desire from Melanesia and beyond. University of Hawaii Press.

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2008). Against war: Views from the underside of modernity. Duke University Press.

Mamdani, M. (1998). Is African studies to be turned into a new home for Bantu Education at UCT? Social Dynamics: A Journal of African Studies, 24(2), 63–75.

Marinetto, M. (2020). Who put the cult in the faculty? https://world.edu/who-put-the-cult-in-faculty/. Accessed 27 March 2022.

Mawere, M. (2021). The deficiency of research in Africa: Towards benefiting from heritage-based research in African Universities. Keynote Speech on Indigenous Knowledge and Epistemic Freedom in the Academy in Support of Cognitive Thinking. South Africa.

McKenna, S. (2013). Introduction in council on higher education (pp. 1–4). Pretoria: Inxon Printing & Design.

Merrett, C. E. (1992). Political censorship in South Africa: Aims and consequences. https://www.sahistory.org.za. Accessed 20 March 2022.

Mohamedbhai, G. (2015). What can be done to tackle corruption? University World News. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=2015060314270811. Accessed 10 March 2022.

Mohammed, W. (2016). 36 years on: Why Walter Rodney was assassinated. Pambazuka News. https://www.pambazuka.org/pan-africanism/36-years-why-walter-rodney-was-assasinate. Accessed 11 March 2022.

Moore, A. (1998). Cultural anthropology: The field study of human beings. Rowman & Littlefield.

Nanda, M. (2003). Prophets facing backwards: Postmodern critiques of science and Hindu nationalism in India. Rutgers University Press.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2013). Perhaps decoloniality is the answer? Critical reflections on development from a decolonial epistemic perspective. Africanus, 43(2), 1–12.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2016). Why are South African universities sites of struggle today? The Thinker, 70, 52–61.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o. (1986). Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature. James Currey.

Nhemachena, A. (2021). Hakuna mhou inokumira mhuru isiri yayo: Examining the interface between the African body and 21st century emergent disruptive technologies. Journal of Black Studies, 52(8), 864–883.

Nishino, R. (2015). Political economy of history textbook publishing during apartheid (1948–1994): Towards further historical enquiry into commercial imperatives. Yesterday & Today, 14, 18–40.

Noth, W. (2003). Crisis of representation? Semiotica, 143(1/4), 9–15.

Nyamnjoh, F. B. (2004). From publish or perish to publish and perish: What ‘Africa’s 100 best books’ tell us about publishing in Africa. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 39(5), 331–355.

Palsson, G. (2008). Genomic anthropology: Coming in from the cold. Current Anthropology, 49(4), 545–568.

Parkin, D., & Ulijaszek, S. (2007). Holistic anthropology: Emergence and convergence. New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Pfaffenberger, B. (1988). Fetishised objects and humanized nature: Towards an anthropology of technology. Man, New Series, 23(2), 236–252.

Pyyhtinen, O., & Tamminen, S. (2011). We have never been only human: Foucault and Latour on the question of the anthropos. Anthropological Theory, 11(2), 135–152.

Rabinow, P. (2016). What kind of being is anthropos? The anthropology of the contemporary. Forum Qualitative, 17(1), 19.

Rabinow, P., & Bennett, G. (2009). Synthetic biology: Ethical ramifications 2009. Systems and Synthetic Biology, 3(1–4), 99–108.

Rabinow, P. (1996). Making PCR: A story of biotechnology. US: The University of Chicago Press.

Rabinow, P. (2003). Anthropos today: Reflections on modern equipment. Princeton University Press.

Radcliffe-Brown, A. R. (1951). The comparative method in social anthropology. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 81(1/2), 15–22.

Ritcher, L. (2011). Cargo cult lean. Human Resources Management and Ergonomics, 5(3), 84–93.