Abstract

This study argues that the under-diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactive disorder in Black children is a result of racism that is structurally and institutionally embedded within school policing policies and the tendency to not recognize Black illness. The purpose of this research is to examine how micro-processes lead to structural inequality within education for Black children. It seeks to better understand how institutional racism and flawed behavioral ascriptions lead to the under-diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) in Black children and how that may also contribute to their over-representation in the “school-to-prison pipeline.” The goal of this study was to review ethnographic, empirical data and examine the ways (1) how racism within some schools may contribute to the under-diagnosis of ADHD in Black children, (2) how their under-diagnosis and lack of treatment leads to their over-punishment, and (3) how they are over-represented in today’s school-to-prison pipeline phenomenon, possibly as a result of such disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children with attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) are more likely to exhibit classroom behavior that warrants punishment (Castellanos and Tannock 2002; Sonuga-Barke et al. 2008; Nigg 2010). However, the basis for punishment in schools has been problematic, and as a result, certain groups suffer more than others indefinitely. But while White children are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than Black children, Black children are disproportionally punished compared to their White counterparts (Healy 2013). Although these are separate disparities, there are substantive reasons to believe that a correlation exists between them. While these disparities may not seem entirely related, they should be considered together as mechanisms of racial inequality in schools. The under-diagnosis of ADHD in Black children and the over-punishment of Black children reflect a long-standing racial inequality that has been systemically reinforced in America for the last several hundred years. This study examines secondary data to contextualize the two processes through an analysis of school settings, while exploring how they might influence one another.

Existing research supports the notion that Black children are under-diagnosed for ADHD compared to White children (Healy 2013) and that Black children are punished with suspensions, and other punishments that lead them to the criminal judicial system, more often than White children are in school (Crenshaw et al. 2015; Smith and Harper 2015). But until now, studies have observed these issues separately, which has left a major gap within the research. This study observes and examines how the under-diagnoses of ADHD in Black children can lead to the disproportionate rates of punishments for Black children in a White supremacist system of schooling and the racial and cultural implications that shape these processes. By studying this, we can better understand the multifaceted and interrelated ways racial discrimination exacerbates social inequalities in our education and judicial systems.

The purpose of this study is not to make empirical assertions about the causal relationship between ADHD under-diagnoses and the over-representation of Black children in the American criminal justice system. There were several limitations that prevented me from conducting such a study that could test that particular notion. As an alternative, this study offers a theoretical intervention into how we view and conceptualize ADHD under-diagnoses among Black children and their over-representation in the criminal justice system by suggesting that we think of these processes as simultaneous and co-constitutive instead of separately. This study also offers a qualitative analysis of one aspect of these co-constitutive processes of under-diagnosis and over-punishment by way of empirical data that depict how administrators, parents, and teachers shape ideas about behavioral disorders and punishment. My main theoretical assertions are the under-diagnosis of Black children has been empirically established and is long-standing with severe social implications; the over-representation of Black children in the criminal justice system has also been empirically established and is also long-standing with severe social implications; ADHD causes children to behave in ways that are often disruptive and outside of the behavioral norms for the typical school environments; therefore, Black over-punishment may be a result of under-diagnosis of ADHD; yet, Black over-punishment may also be a result of schools’ tendencies to see the behavior of Black children differently than they do the same behaviors when they occur among White children. In short, this study shows why we need to better explore the role ADHD plays in the over-representation of Black children in the criminal judicial system, as well as how meanings attached to Black children’s behaviors by teachers, administrators, and parents shape both under-diagnosis and over-representation.

How ADHD Affects Children’s Classroom Behavior

Over five million children under the age of 18 have been diagnosed with ADHD in the USA, which consists of approximately 9 % of all of the children in the country who are currently within that age range (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014). Symptoms for this disorder can appear as early as preschool, which will be become a relevant factor later on in this study. There are no studies that explain how these characteristics can truly have an impact on one’s probability of being punished if the child is left untreated.

Bullying, fights, and significantly high levels of impulsivity and aggression are common for children with ADHD (Castellanos and Tannock 2002; Sonuga-Barke et al. 2008; Nigg 2010). These children are at a higher risk for committing delinquent behavior in their adolescence and criminal activity in their adulthood, and they are more at risk for substance abuse at a young age (National Institute of Mental Health 2014). Researchers believe that these children may be using drugs and alcohol as a way to self-medicate their condition or to cope with the emotional and social issues that are linked to ADHD (NIMH 2014). ADHD’s negative outcomes can lead to delinquent behavior that would be punished by school suspensions; this is particularly unfortunate for Black children who are already punished much more harshly (Crenshaw et al. 2015; Smith and Harper 2015), and at higher rates, compared to their White counterparts, whether or not they have ADHD. As a result, it stands to reason that the punishment related to these issues are compounded when the children are Black—they are over-punished whether or not they have the disorder, but their disadvantages in the classroom are exacerbated when they are Black with ADHD. Thus, we may surmise that there are indeed mechanisms contributing to Black children’s over-punishment and their over-representation in the criminal justice system at an early age. The over-representation of Black children in the “school-to-prison pipeline” will be examined more in depth in later sections of this work.

Contrary to some people’s beliefs, ADHD does not affect a child’s level of intelligence. It can, however, cause low academic performance (Loe and Feldman 2014). Inattention, reading difficulties, and even handwriting issues can create academic challenges for children (Racine et al. 2008). Unfortunately, for many children with this disorder, underachieving is not uncommon and neither is repeating a grade level in school. All of these factors that contribute to low academic achievement can affect how a student feels about him- or herself; teasing and alienation from classmates and teachers can influence a child’s self-esteem and/or self-confidence. This is why children with ADHD often behave in ways that are disruptive and counter-productive. The majority of the characteristic implications for children with ADHD would warrant school suspensions based on infractions related to classroom misbehavior. As stated earlier, combatting some of these challenges is much easier for students who are able to seek treatment and gravely impossible to combat for students who are unaware that they even have the disorder. This factor, and other additional factors, will be discussed later. But first, the racial disparities within the diagnoses of ADHD for children should be examined.

Racial Disparities in ADHD Diagnoses

Black boys and girls are punished at significantly higher rates than their White counterparts (Crenshaw et al. 2015; Smith and Harper 2015). Racial prejudice cannot solely explain why there is a racial inequality for ADHD diagnoses. Yet, researchers have taken different approaches, specifically examining the intersection of race and socioeconomic status, and have found that race is always the most significant factor that explains under-diagnosis even when SES is controlled in the study. The nationally representative “Early Childhood Longitudinal Study: Kindergarten Class of 1998–1999” provided a quantitative analysis that was based on the parent reports of 17,100 children (Healy 2013). What they found was that approximately 7 % of White children had been diagnosed with ADHD and most of these diagnoses occurred at some point between kindergarten and eighth grade (Healy 2013). By the same measure, only 3 % of Black children had been diagnosed by middle school, which is about less than half in comparison to White children (Healy 2013). (Boys, who were more likely to engage in fighting, bullying, and other behavioral problems, were twice as likely to be diagnosed regardless of race and ethnicity.) The odds of being diagnosed with ADHD were almost 70 % lower for Black children, 50 % for Latino children, and 46 % lower for children of other races and ethnicities (Healy 2013).

Compared to the White children in this study, the use of prescription medication was also lower for all racial and ethnic minorities. The odds for prescription medication use were 65 % lower for Black children, 47 % lower for Latino children, and 51 % lower for children of other races and ethnicities (Healy 2013). Not only are the statistics for Black children in this study unfavorable compared to White children, but they also reflect a disparity in which Black children are at the very bottom out of all minority children. Associate Professor of Education at Penn State University Paul Morgan, and lead author of the journal Pediatrics, has stated, “There’s no reason to think that minority children are less likely to have ADHD than White children, so these are worrisome findings that suggest a systemic problem,”; Morgan was referring to the healthcare system and counseling system within schools, and how those systems have not been effectively evaluating, diagnosing, and treating these children, thus failing to meet the needs of many Black and other minority families. He went on to say that, “…research has already identified a range of different effective treatments for ADHD, including medication, behavioral therapy, specialized educational programming and parent training…These findings suggest that children who are racial and ethnic minorities are not accessing those treatments because they are comparatively underdiagnosed.”

Research provides many suggestions for why Black children may be under-diagnosed. Some suggest that this racial disparity exists because there is a racial bias within the classrooms and judicial systems that does not favor Black children (Rudd 2014). But, less obvious reasons include (1) a general lack of awareness about ADHD (Ahmann 2013), (2) the lack of social networks in the Black community (Horn et al. 2004), (3) cultural misconceptions of students’ behavior among teachers, administrators, and healthcare providers (Davidson and Ford 2001), and (4) social stigma attached to behavioral disorders (Davidson and Ford 2001). Furthermore, the process of evaluating and diagnosing students can be very expensive, which would disproportionately affect Black families, who tend to have less wealth and income than their White counterparts. Black people, unfortunately, are disproportionately uninsured or underinsured (Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2014), which can limit their ability to afford evaluations and effective treatment. But, there are other less apparent factors that add to these under-diagnoses. I consider them in the following sections.

Lack of Awareness

The lack of awareness was mentioned earlier as a prominent factor for why the inequality exists. First, research suggests that there is an existential lack of awareness about ADHD among Black people. The Journal of the National Medical Association published a study called “ADHD Among African-Americans” (Ahmann 2013); the study strongly suggests that African-Americans are simply unfamiliar with ADHD, what causes it, and how it can affect their children’s behavior if it is left untreated. According to the study, just less than 70 % of Black parents had even heard of ADHD (Ahmann 2013). Additionally, less than 40 % of Black parents had accurate and reliable information about the disorder; for example, barely 10 % of Black parents knew that ADHD is not caused by too much sugar in a child’s diet (Ahmann 2013). This tells us that Black parents are generally uninformed about ADHD and therefore, they do not even know that they should be seeking help for their child in the first place.

Lack of Social Networks

Black people also tend to lack access to the social networks where issues such as ADHD and other learning disorders are prevalent and frequently discussed. ADHD is still very much a White middle-class issue primarily. As a result of lack of awareness, some Black parents actually believe that their children, who may have ADHD, simply have behavioral issues that can be solved by corporal punishment at home. Research shows that Black parents are more likely to practice corporal punishment than White parents, so these beliefs are not uncommon (Horn et al. 2004).

Cultural Misconceptions and Stigmas

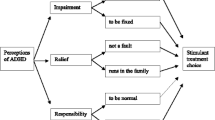

Cultural perceptions also play a major role in the under-diagnoses of Black children. The Journal of Negro Education published an article of a study entitled “Perceptions of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in One African-American Community” (Davidson and Ford 2001), where researchers examined how and why Black parents view ADHD and other learning disabilities differently. The researchers conducted an ethnographic study in an “urban” school district; the study consisted of forty-five hours’ worth of semi-structured interviews with 25 participants. The participants consisted of Black parents and educators, and healthcare professionals who primarily work with Black parents and their children. The goal of the study was to examine the beliefs and perceptions about ADHD that are held by lower socioeconomic status Black families. Overall, they found that Black parents tend to view diagnoses for ADHD, and other disorders that require attention and medical support, as a social stigma for their children (Davidson and Ford 2001).

In addition, if diagnosed and treated, the child would be known for taking “drugs,” which is another stigma for Black children who are already a marginalized group in the USA. In fact, a nurse concluded during the study that “African-American parents always indicate a fear that using Ritalin will lead to drug abuse later on” (Davidson and Ford 2001). The fear of drug abuse alone is a major factor in why many Black parents are reluctant to seek medical treatment for their children’s behavior. Black parents generally felt that by treatment with drugs as a solution for bad behavior, their children would become dependent on them instead of just fixing their own behavior. Even though White people are more likely to use and abuse drugs (McCabe et al. 2007), the Black community is generally much more concerned about the potential misuse of Ritalin and other prescription drugs.

In contrast, this study found that when White parents were examined, ADHD was never thought of as a social stigma for their children (Davidson and Ford 2001). White parents commonly showed signs of relief when the possibility of their child having a documentable learning and behavioral disorder emerged; it was as if they had been searching for a justified, biological excuse to help explain why their child struggles with inattention and hyperactive behavior in a school setting. They also expressed very little concern about their children becoming susceptible to drug addiction after being given prescription drugs; they went on record to say that the use of Ritalin and other drugs are seen as “preventative” measures that would hopefully yield positive outcomes for their children (Davidson and Ford 2001). Furthermore, White parents were much quicker to embrace all of the benefits that come with being diagnosed with ADHD. Conversely, Black parents’ view of ADHD as a stigmatization impeded their ability to accept a diagnosis as a mechanism for gaining access to accommodations. The medicinal treatments were obviously seen as a benefit. Children who have been diagnosed receive specific accommodations that other children do not typically have access to, such as extra time on tests, academic support, and special education programs. Some would even suggest that White children are over-diagnosed for ADHD and other learning and behavioral disorders (Schneider and Eisenberg 2006). Regardless of whether or not that stands to be true, it is obvious that one group is fully taking advantage of these services, while the other group is failing to have its needs met. But, there are many more factors that contribute to the under-diagnoses of Black children.

Black People’s Mistrust of Institutions

Historically, Black people in general have been less likely to trust their own healthcare professionals and America’s healthcare system as a whole. This distrust is a result of the countless ways in which Blacks have been discriminated against and treated wrongly by professionals. In this country, two of the most prominent institutions in which Blacks have been affected are education and healthcare. After the landmark US Supreme Court decision of Plessy v. Ferguson, the “separate but equal” doctrine was enacted, and although it was abolished some decades later after the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954, many schools remain segregated and unequal as a result of years of legislation and policies that have not favored Black children. In 2010, the US government officially apologized for the horrible and unethical ways in which Black men were exploited by researchers and physicians during the Tuskegee syphilis experiment over 60 years ago (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1997). Unfortunately for Black people, this was not the only time in American history where Black people were taken advantage of for the sake of scientific advancement or as a result of racial prejudice. In fact, there were many other instances in American history, reported and unreported, in which Black people were taken advantage of by the healthcare system in some way (Washington 2006). Also, the fact that Black healthcare professionals are limited (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2006) does not make it easier for Blacks to put their trust in the hands of others; maybe if minority healthcare professionals were more represented in healthcare, Black people would be less likely to lack trust in physicians.

Members of the Black community also fear being wrongly diagnosed by physicians and for good reasons. Black parents lack faith in educators and administrators that do not, and cannot, understand their culture for the sake of meeting the needs of their children (Davidson and Ford 2001). This current system is set up to fail Black children.

The issue of Black children bonding with their teachers is another crucial factor that explains why Black families tend to lack overall trust in their school’s ability to weigh in on their children’s behavioral issues. For several years, research has shown that that the bond fails to develop frequently because there is a lack of cultural congruency between Black children and their educators and authoritative figures in school (Delpit 2011). But, unfortunately, the lack of bonding leaves Black families at a terrible disadvantage and their children do not get the appropriate help and resources that they need to make the most of their educational experience. In order for professionals to fully interpret and evaluate the behaviors that are commonly exhibited by Black children, they must know and understand at least most of the underlying experiences that affect how the children act and react under certain circumstances.

Perceived differences in culture are what cause the fundamental divide in how Black parents view ADHD treatment compared to how White educators view ADHD treatment. But even beyond that, deeper cultural implications suggest that Black children are at a disadvantage in a classroom setting compared to children of other races.

Sociologists and other African-American Studies scholars have theorized that bold assertiveness and self-expression, which are behavioral traits that could easily warrant behavioral infractions in school, are highly common and even encouraged within Black culture (McNeil et al. 2002). On the contrary, the members of the White community tend to place value on their ability to hold back and control their impulses regularly. As a result, many Black parents view treatment for ADHD, such as Ritalin and other drugs that force children to “settle down,” as substances that will “take the spirit” out of their children. This suggests that Black parents fear that their children will lose what essentially makes them “Black” and conform to what they may see as boring standards of those set by their White counterparts.

How Culture Influences Differences in Perception of Behavior

Cultural differences in perceptions of behavior and communication within the classroom are often very problematic, particularly for Black children. There is a strong possibility that perceived misbehavior and inattention usually stems from a relationship issue with the teacher or parent. Whether or not people choose to acknowledge racism as a reason for this disconnect between Black children and their teachers, it is still clear that the cultural and social disconnect exists. Thomas Kochman (1983), author of Black and White Styles in Conflict, examined the cultural practices and conflicting styles of White people and Black people. He achieved this by doing a study that closely observed the different ways in which Black and White people interpret arguments and discussions. Kochman found that Black people tended to perceive the dialog as “discussions” and methods for directly clearing the air and being honest; White people in comparison viewed the dialog as “arguments,” and they perceived argumentative methods to be dysfunctional ways of solving discrepancies. The study further showed that the directness of Black parents made the White middle-class teachers uncomfortable simply because they are not used to that level of directness.

The Difference Between Parents’ and Teachers’ Perceptions of Children’s Behavior

The lack of a rapport between White middle-class teachers and Black parents, particularly working-class and low-income parents, also contributes to negative outcomes for Black children. In the study mentioned earlier (Davidson and Ford 2001), the blunt approaches made by Black parents often left White teachers intimidated. A Black teacher pointed out, “I think a lot of teachers are really afraid of African-American parents. They’re afraid parents are going to be upset [when suggesting the child should be tested for ADHD].” The researchers were sure to point out, however, a particular White teacher who was able to successfully build a rapport with Black parents after simply putting in the time and effort. During her interview, she stated, “With my parents, mostly the reaction [to a behavioral or learning problem] is, ‘We don’t really know what to do. You tell us and we’ll do it.’” This compliance was remarkable because it showed that once the personal biases between the parents and the school were removed, Black parents were more willing to take heed to what the teacher was recommending for the sake of the student. The parents may have still been hesitant to seek medical advice, but they were less defensive and more willing to accept the fact that their child may have a behavioral disorder and, more than likely, a learning disability. Furthermore, they were more willing to seek advice from medical healthcare professionals and were much more receptive to their suggestions which, of course, benefitted the child. Many teachers, unfortunately, are still unable to create this space for a rapport to develop.

Institutional Racism and the School-To-Prison Pipeline

All of these issues clearly indicate that there is definitely institutional racism within our education system and it is affecting Black children in a very negative way. Unfortunately, the false idea still exists today that Black parents do not care about their children, when in fact, there are several racial, cultural, and even sometimes political forces acting simultaneously to discourage Black parents from trusting institutions that have been put in place to serve their children. These forces are what contribute to the under-diagnoses of ADHD in Black children compared to White children. But, the institutional racism does not end there for Black children.

Over the last several years, there have been cases of racial discrimination against Black children that have brought to light many social injustices that have been significantly impeding their educational advancement. A prominent example of blatant racial discrimination while policing in schools was the United States v. City of Meridian case in 2012. The justice system in Mississippi was exposed for the way it had been harshly punishing Black children for minor infractions at alarming rates, and it even illuminated their neglect to respect these same students’ amendment rights upon their arrests (United States District Court Southern District of Mississippi 2012). In this case, a total of 77 children, all of them children of color, were arrested and thrown into a juvenile detention facility for breaking minor rules in schools. These infractions were not even considered violent behavior but instead disruptive disobedient acts such as leaving the classroom without permission to use the bathroom, being tardy to class, and behaving rudely towards an administrator. According to the case, these students were placed in handcuffs and immediately taken to juvenile facilities with no hearing. In addition to their harsh punishments, the children were not given due process as they were coerced into confessions before they were read their Miranda rights. Cases like this one were not exclusive to Mississippi; this form of prejudice has been occurring over the last several years in Arkansas, California, New York, Kentucky, Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia (Kauffman 2012; Smith and Harper 2015). These injustices were becoming so common that the term school-to-prison pipeline, a term that had never been used before, was created in order to address this major issue. Under-diagnosis and over-punishment are two prevalent issues for Black children, but mass imprisonment is just as pertinent as any other social problem for Black people.

As we know, Black children are disproportionately represented in what is now known as the school-to-prison pipeline, compared to White children (Elias 2013). In short, the school-to-prison pipeline is the system in which teachers and administrators refer students to the juvenile court system who have breached the existing behavioral code of conduct. This system becomes extremely harsh for Black children when it is coupled with the nationally mandated “no-tolerance” policies that are specific to each individual school. Originally, the no-tolerance policy was put in place as a result of the shootings at Columbine High School in Littleton, CO, 15 years ago (Kang-Brown et al. 2013); it prohibited any tolerance of weapons and other harmful objects within the school walls. However, over time, no-tolerance policies developed into policies that each individual school chose to implement based on their own preferences. This has caused a huge controversy because it has allowed schools to send students to juvenile detention centers over the most minor infractions, such as wearing the wrong color socks at school where uniform dress is mandatory. These policies have allowed teachers and administrators to abuse their power to send children with behavioral issues to prison, in addition to suspending them from school.

There is major a systematic flaw that exists within the school-to-prison pipeline. Simply put, this pipeline increases the likelihood of a child being introduced to the criminal justice system. And during the 1980s, as the government began to arbitrarily declare a “war on drugs,” and as crack cocaine was being introduced to poor Black neighborhoods, the USA began mass incarcerating people for non-violent crimes and giving them harsh sentences if they had been convicted of a drug crime (Alexander 2010). Studies have shown that when people are introduced to the criminal justice system during their childhood, they are more likely to drop out of school and end up in prison when they get older (Fabelo et al. 2011). This is problematic particularly for Black children, who are unfairly over-represented in this system. According to a nationwide study done by the US Department of Education for Civil Rights, Black children are three and half times more likely to be suspended or expelled from school than their White counterparts (Elias 2013). This is alarming, especially considering that Black children only make up about 15 % of the student population in the USA (U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics 2013). Forty-six percent of all of the students who are suspended more than once are Black, and 32 %of all children in juvenile detention centers are children with learning disabilities (Elias 2013); one out of four Black children with disabilities are suspended at least once, while only one in 11 White students with disabilities are suspended at least once (Elias 2013). Here, it is apparent that even with the under-diagnoses of ADHD in Black children, there is an overwhelming disparity in how Black children with disabilities are punished in comparison to how White children with disabilities are punished by schools.

Conclusion and Implications for Future Research

This study has outlined and qualitatively assessed three processes in school inequality for Black children in America: (1) the under-diagnosis of ADHD among Black children, (2) the over-punishment of Black students in schools as a result of racist practices within schools, and (3) the over-representation of Black children in the school-to-prison pipeline phenomenon. My theoretical argument still stands as such: Black children have been severely under-diagnosed for ADHD and other learning disabilities compared to White children; Black children are and have been significantly over-represented in the criminal justice system compared to White children; ADHD yields problematic behavior for children in schools; thus, the over-punishment of Black children may possibly be a result of under-diagnosis of ADHD and other societal forces that are continuously at work; yet, Black over-punishment may also be a result of schools’ tendencies to perceive the behavior of Black children differently than they do when White children exhibit similar behaviors. This study also highlights the ways in which Black parents may aid in preventing their children from being assessed and diagnosed based on their own skeptic views of healthcare and their fear of compounding their children’s innate stigmatization of Blackness with being labeled as disabled. Based on these quantitative and qualitative data, we can conclude that Black children are being set up for failure that will affect them exponentially as they grow older, as a result of these disparities.

Current literature provides a strong basis for the ideas surrounding Black children’s under-diagnoses and their over-representation in the criminal justice system, but more investigation is needed on the subject of the over-punishment of Black children and the mechanisms that influence the outcomes of this inequality. We know some sort of racial bias does exist in classrooms. A relatively recent study showed that Black children, even as early as preschool, are more than likely to be suspended than White children—even at the tender age of four (Demby 2014). Black students are more likely to be suspended than White students, Black students tend to commit less harsh infractions in school than White students, and yet they are more likely to receive harsher punishments.

Overall, this study shows the importance of gaining a better understanding of the way in which disparities in ADHD diagnoses affect the over-representation of Black children in the criminal judicial system, in addition to how Black children’s behaviors are perceived by teachers, administrators, and parents. We can suggest that Black children are not able to learn as much because they consistently are being kept out of schools at alarming rates as a result of current no-tolerance policies. More specifically, less culturally aware and inexperienced teachers who are placed in failing schools may be quicker to remove “disruptive” students from their classrooms as they are already under pressure to get their students to achieve certain scores on standardized tests. Not only are Black students spending more time outside of the classroom than their White classmates, but they also are being somewhat controlled by a flawed system that is already saturated with institutional racism. Also, we can conclude that some Black children may be over-punished as a result of them not having access to effective evaluations, diagnoses, and treatments for behavioral and learning disorders that are very prevalent for American children, such as ADHD. This is how the under-diagnoses of ADHD in Black children impacts their likelihood of ending up in the school-to-prison pipeline, further increasing social inequality between Black people and White people in America. Much more sociological attention is needed in these areas if we hope to eradicate these disparities.

References

Ahmann, E. (2013). ADHD among African-Americans. Psych Central. Retrieved on April 24, 2014 (http://psychcentral.com/lib/adhd-among-african-americans/00017250).

Alexander, M. (2010). The New Jim Crow. New York: The New Press.

Castellanos, F. X., & Tannock, R. (2002). Neuroscience of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the search for endophenotypes. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3, 617–628.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1997). Remarks by the president in apology for study done in Tuskegee. U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. (http://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/clintonp.htm).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Retrieved on October 1, 2014. (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/adhd.htm).

Crenshaw, K., Ocen, P., Nanda, J. (2015). Black girls matter: pushed out, overpoliced and underprotected. Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies at Columbia University.

Davidson, J. C., & Ford, D. Y. (2001). Perceptions of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in one African-American community. The Journal of Negro Education, 70(4), 264–273.

Delpit, L. D. (2011). The silenced dialogue: power and pedagogy in educating other people’s children. Harvard Educational Review, p. 280–299.

Demby, G. (2014). Black preschoolers far more likely to be suspended. NPR. Retrieved on April 27, 2014 (http://www.npr.org/blogs/codeswitch/2014/03/21/292456211/black-preschoolers-far-more-likely-to-be-suspended).

Elias, M. (2013). The school-to-prison pipeline. Teaching tolerance: a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. Number 43.

Fabelo, T., Thompson, M. D., Plotkin, M., Carmichael, D., Marchbanks, M. P., Booth, E. A. (2011). Breaking schools’ rules: a statewide study of how school discipline relates to students’ success and juvenile justice involvement. Retrieved on October 1, 2014 (https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=266653).

Healy, M. (2013). Under-diagnosis of ADHD begins early for some groups. Retrieved on April 27, 2014 (http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/06/24/adhd-minorities-diagnosis/2439647/).

Horn, I. B., Joseph, J. G., Cheng, T. L. (2004). Nonabusive physical punishment and child behavior among African-American children: a systematic review. The Journal of the National Medical Association, 96(9).

Kang-Brown, J., Trone, J., Fratello, J., Daftary-Kapur, T. (2013). A generation later: what we’ve learned about zero tolerance in schools. Vera Institute of Justice, Center on Youth Justice (http://www.vera.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/zero-tolerance-in-schools-policy-brief.pdf).

Kauffman, E. (2012). The worst ‘school-to-prison’ pipeline: was it Mississippi? Time Magazine.

Kochman, T. (1983). Black and white styles in conflict. University of Chicago Press.

Loe, I. M., & Feldman, H. M. (2014). Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

McCabe, S. E., Morales, M., Cranford, J., Delva, J., McPherson, M. D., & Boyd, C. J. (2007). Race/ethnicity and gender differences in drug use and abuse among college students. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 6(2), 75–95.

McNeil, C. B., Capage, L. C., & Bennett, G. M. (2002). Cultural issues in the treatment of young African American children diagnosed with disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27, 339–350.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2014). Retrieved October 1, 2014. (http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/index.shtml).

Nigg, J. T. (2010). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: endophenotypes, structure, and etiological pathways. Current directions in psychological science. Retrieved on October 1, 2014. 19:24–29.

Racine, M. B., Majnemer, A., Shevell, M., & Snider, L. (2008). Handwriting performance in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Journal of Child Neurology, 23(4), 399–406.

Rudd, T. (2014). Racial disproportionality in school discipline: implicit bias is heavily indicated. Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at The Ohio State University.

Schneider, H., Eisenberg, D. (2006). Who receives a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United States elementary school population? Pediatrics, 117(4).

Smith, E. J., & Harper, S. R. (2015). Disproportionate impact of K-12 school suspension and expulsion on black students in Southern States. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education.

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S., Sergeant, J. A., Nigg, J., & Willcutt, E. (2008). Executive dysfunction and delay aversion in ADHD: nosologic and diagnostic implications. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America., 17, 367–384.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2013). Digest of Education Statistics, 2012 (NCES 2014–015), Ch. 3.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2006). The rationale for diversity in the health professions: a review of the evidence. Retrieved on October 1, 2014. (http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/diversityreviewevidence.pdf).

United States District Court Southern District of Mississippi. (2012). United States v. City of Meridian.

Washington, H. (2006). Medical apartheid. New York: Random House.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Zandria Robinson, Anna Mueller, and Wesley James for their advisement during this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moody, M. From Under-Diagnoses to Over-Representation: Black Children, ADHD, and the School-To-Prison Pipeline. J Afr Am St 20, 152–163 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-016-9325-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-016-9325-5