Abstract

The presence of African American women at predominantly white institutions is one of historical relevance and continues to be one of first, near misses, and almosts. Individually and collectively, African American women at PWIs suffer from a form of race fatigue as a result of being over extended and undervalued. The purpose of this article is to present the disproportionate role African American women assume in service, teaching, and research as a result of being in the numerical minority at PWIs. Information is presented to provide an overview on racism in the academy, images and portrayals, psychosocial, spiritual, and legal issues for African American women faculty. Finally recommendations are presented to assist African American women faculty, and administrators, colleagues, and students at PWIs to understand and improve the climate at their institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Individuals of African descent represent a unique group who hold a specifically differentiated place in history throughout the world and, in particularly in the United States (i.e., African Americans) because of slavery and its subsequent effects. Within the last century African Americans were systematically barred from full and equal participation in larger society, the classic blues and jazz had not emerged as the defining forms of American music, “separate but equal” was the institutional law of the South and the de facto law of the land, racist “sambo” images of blacks proliferated in advertisement (Gates and West 2000), the portrayal of Black women as mammies (Collins 2000) and men as studs, and stereotypical images as hyper-sexed deviants were prevalent. Despite these circumstances and negative portrayals African Americans are a composite of cultural richness and entertainment genius, entrepreneurial spirit and inventors, civil rights and social justice advocates, religious leaders and political thinkers, educators and mentors, and national visionaries. In essence, African Americans are extraordinary individuals, with historic and contemporary experiences, wisdom, and life lessons to create an invaluable template for generations to come. In fact, American life and education is inconceivable without its black presence (Cosby and Poussaint 2004; Gates and West).

In this article the focus is on African American women in academia. African American women in the academy differ in experiences, background, and beliefs; however, they are connected in their struggle to be accepted and respected, and to have a voice in an institution with many views (Collins 2001). Many of the experiences of African American faculty in general also cut across African American women faculty and affect them disproportionately. Unlike their white female professionals who are daughters of white men and, subsequently benefactors of white privilege, African American women at PWIs are overwhelmingly recipients of deprivileged consequences. To be deprivileged illustrates why African American women faculty are metaphorically referred to as the maids of academe. Deprivilege is played out in various ways at PWIs and within the requirements of the professorate. The maid syndrome becomes more evident when African American women remain at PWIS, where many abuses constantly beset their sensitiveness (McKay 1997). In PWIs, misconceptions and stereotypes about race and gender lead to the (mis)treatment of and interaction with African American women as a label, thus devaluing the real person behind the stigma and encouraging self-fulfilling prophesies by the gender and race that hold power (Kawewe 1997). Specifically, African American women are subjected to “gendered racism.” For example, African American women are told often by white women that they would be happier if they returned to an historically black college and university (HBCU) (i.e., go back to where you came from—even if they had not come from one) after receiving their degree from and teaching at a PWI because this gives them added prestige in HBCUs (McKay 1997). Further discussion of African American women faculty’s roles as symbolic to maids are presented later in this article.

African American women administrators and faculty are largely concentrated in HBCUs (Benjamin 1997). The exact number and percentage of African American faculty at PWIs vary depending on the source and year of data collection. However, the consensus is that over 90% of faculty members at PWIs are white, and predominately male at the rank of full professor. According to Washington (1997), “since the academy is a workplace that has historically favored white males, stories behind the statistical reality today are particularly telling” (p. 272). In addition, the gap between the percentage of tenured men, tenured women, and African American women has not changed in 30 years (Trower and Chait 2002). The journey of African American women faculty at PWIs is one of historical events and continues to be one of firsts (e.g., Tracey L. Meares as the first African American woman to join the Yale Law School faculty in January, 2007), and of sexual and racial obstacles in white academic milieus. Too often, African American women’s participation in higher education and the impact of racism and sexism on them in the academy have been absent from the research literature (Collins 2001).

Historically, the field of education is familiar ground for African American women since it was always one of the few respectable professions open to the group (McKay 1997). Documentation of African American women’s involvement in education began during slavery and as [formal] educators around the 1850s. These women entered the academy (i.e., institutions for blacks) as heads of specialized nurse training schools and as deans of women (Wolfman 1997). At predominately white institutions (PWIs) African American workers labored in service-related occupations. One of the important consequences of the civil rights and Black power movements was the creation of new employment opportunities for African American scholars at PWIs (Weems 2003).

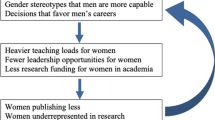

African American women have been participants in higher education for more than a century; however, they continue to be seriously underrepresented among faculty ranks (Bradley 2005). The role and presence of African American women in white institutions of higher education in the United States is characterized by “white supremacy” (i.e., internalize racial wounding and the accepted notion of aesthetic inferiority in relation to whiteness), not just “racism” (i.e., covert and overt racial aggression) (Hooks 2001). In addition, many African American women faculty at PWIs find themselves caught between race and gender. African American women have been jeopardized because of being both black and female (Williams 2001). For their lives are inextricably linked to a history of racist and sexist oppression that institutionalizes the devaluation of African American women as it idealizes their white counterparts (Collins 2000). Overwhelmingly, African American women are not incorporated into the mainstream of the campus’s academic culture at PWIs (Alfred 2001a; Turner and Myers 2000) and receive fewer opportunities for collaborative research than their female counterparts (Turner 2002). Individually and collectively, African American women at PWIs suffer from a form of race fatigue – the syndrome of being over extended, undervalued, unappreciated, and just knowing that because you are the “negro in residence” that you will be asked to serve and represent the “color factor” in yet another capacity. Carter et al. (1988) best summarized the plight of African American women faculty as “one of the most isolated, underused, and consequently demoralized segments of the academic community” (p. 98). As PWIs seek to hire African American women for faculty positions they need to be reminded of the problems encountered as part of academic apartheid (Harley 2001).

In 2001, Harley published an article entitled “In a Different Voice: An African American Woman’s Experiences in the Rehabilitation and Higher Education Realm.” As part of that article information was presented on a perspective of being an African American woman at a PWI and recommendations were offered as to what women in general needed to do to survive in the system. In addition, the intersection of race and gender was addressed to reflect the compounded position of being African American and female within this context. In the current article the focus is to further expand on the intersection of race and gender of African American women at PWIs and to draw attention to the disproportionate role assumed in service, teaching and, ultimately in research regarding multicultural and minority issues. Information is presented to provide an overview of African American women with regard to (a) racism in the academy, (b) constructed profiles of African American women’s roles in PWIs, (c) psychosocial adjustment and coping issues of being a numerical minority, (d) physical and spiritual consequences, and (e) legal issues for women of color at PWIs. In addition, specific recommendations and strategies are provided to assist African American women faculty and administrators, colleagues, and students at PWIs to respond to challenges of social justice and respect in the academy. It is the intent of this article to identify the multiple issues faced by African American women faculty and to offer the reader some insight and direction to disrupt the systemic misogynist and racial arrogance at PWIs. In addition, for non-African American readers, the goal is to increase their level of awareness and realization that advocacy must be both symbolic and active—one must not only believe that social justice is to be supported but one must actively support, promote, and implement steps to achieve it.

Racism in the Academy

Although institutional racism, sexism, and the intersection of the two have been part of conversations at PWIs, there is still no effective language to name the ways universities police their boundaries or to help identify the allusive forms of racism [and sexism] that haunt the academy (Back 2004). However, one plausible explanation is offered by Rangasamy (2004) who reviewed the intersection of racism and sexism as a relational existence between “the status quo and its key institutional functions are reliant on the exercise of power.” “Institutional language offers interesting parallels with political language in which the body of rules and regulations by which institutions operate are inspired or influenced by political agendas” (p. 29). According to Back, “most white academics consider it unreasonable that an accusation of racism should be leveled at them” because they believe “that the face of racism is that of the moral degenerate, the hateful bigot” (p. 4). The resentment of the accusation is deeper than a response of being accused of something that is so vile. In fact, what raises their blood pressure is that something (i.e., theft of all that is mannerly about liberalism, knowledge and educational progress) is being taken away. Thus, to accuse academics of racism is perceived as tantamount to taking their education away from them. Ironically, many white academicians are sensitive to what demonizes them, but not to how African Americans are demonized. For it is this reason why it is practically impossible to have a measured and open debate about racism in the academy (Back). West (1993) further argues that in order to engage in a serious discussion of race in America, “we must begin not with the problems of black people but with the flaws of American society—flaws rooted in historic inequities and longstanding cultural stereotypes” (p. 6). Because of many of these flaws blatant racism surfaces periodically and covert racism continues to permeate the institutional climate of many PWIs (Back 2004; Harley 2001; Thompson and Louque 2005; Turner and Myers 2000; Williams 2001).

Gulam (2004) acknowledged that “there have been slight, and probably transitory, indications that PWIs may be compelled to consider the multi-faceted dimensions of race within overall operational life” (p. 7). However, the societal momentum generated by the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, and various alliances for social justice have yield limited and unsustainable efforts. Much of the resistance to diversification of PWIs and the continued institutional racism is rooted in cultural history, formed during colonial history, and deeply manifested in the collective psyche. Institutional racism is described by Rangasamy (2004) as (a) a symptom of fundamental maladjustment in the interactions of culturally and ethnically differentiated beings, (b) a virus with immunological competence from and against the very remedy designed to neutralize its effects, (c) generations of embedded patterns of disparity with overt and insidious intent that underlines every act of discrimination, and (d) protocols of collective decision-making based on negative and disparaging assumptions that provide effective camouflage for bigotry. Each of these descriptors helps to show how institutional racism can survive and anew itself in more resilient forms in response to changing circumstances.

In many ways racism exists at PWIs because one of the core principles of the power of whiteness is its “positional privilege” of being racially unmarked and invisible (Hooks 1992). The positioning of whiteness as the norm of measurement in the United States has legitimized it in such a way that it is taken for granted and is naturalized to the point of being invisible (Purwar 2004). Mills (1997) offered the following analogy to illustrate the invisible norm of whiteness: “the fish do not see the water and whites do not see the racial nature of a white polity because it is natural to them, the element in which they move” (p. 76). At PWIs, African American faculty members feel and live with the weight of both white invisibility and black visibility. In essence, African Americans are not seen as native in the academy, and black bodies are imagined politically, historically, and conceptually circumscribed as being out of place (Cresswell 1996; Purwar). However, African American faculty may be given a sort of diplomat status in certain disciplines in academe (e.g., fine arts) because they can perform (i.e., sing and dance) for the enjoyment of others. This is not to say that talents of African Americans are not to be acknowledged and appreciated but to illustrate, within a dichotomy, how African Americans are simultaneously valued and stigmatized. Frequently, African Americans still are not seen as talent and competent faculty but as “black” faculty—a segregated distinction with certain references to special hires and affirmative action quotas.

Profiling of African American Women’s Roles at PWIs

The images of African American women are prescribed and controlled by sources internal and external to the black community. Images of African American womanhood in the black community are negotiated by various entities including family, church, duality (i.e., participants in two cultures), and views prevalent at HBCUs. Externally, images of African American women are too frequently defined and dictated by whites, who either are unaware, unwilling, or unable to recognize the extent of racism and sexism in the university climate (Collins 2000), categorization and ghettoization of intellectual value (e.g., they can teach diversity courses but not research), marginalization, and arrogance in the academy. African American women faculty often observe that when they voice their opinions about issues, they are labeled as trouble makers, a special interest group, or as crying wolf. Conversely, when African Americans seek “social separation” (i.e., the separation of the workplace from personal lives) (Wolfman 1997) they are viewed as nonconformist and antisocial. According to Collins (2000), “African American women’s status as outsiders becomes the point from which other groups define their normality” (p. 70). In fact, African American women are simultaneously essential for society’s survival because as they stand at the margins of society by not belonging, its boundaries emphasize the significance of belonging.

In general, African American faculty must cope with cultural insensitivity and sometimes just plain stupidity from students, colleagues, administrators, and staff in the academy (Thompson and Louque 2005). As an already marginalized population, African American women faculty members are more often reprimanded by their dean and criticized by colleagues based on supposition, misperceptions, and on information without merit. Whenever such responses occur they compromise the professional integrity of African Americans, contaminate their professional experiences, and further highlight the politics of being an African American woman in higher education (Jarmon 2001). Within the academy African American women simultaneously assume the roles of scholars, researchers, educators, mentors, service providers, and social change agents. In addition, as African American women faculty members take the journey in the academy and move toward the tenure and promotion process with aspirations for advancement up the hierarchy of supervisory, management, and administrative goals, they are frequently “tagged as it” or the “go to person” for issues of diversity. In some ways their credibility and capital increases, but only within the realm of diversity. That is, not only do they perform the “expected” tasks and professional responsibilities of the professorate, they are also the advocates for black issues, translators of black culture, navigators of a patriarchal and racial minefield, community liaison, and conduits for others’ problems. Yet, in these various formal and informal roles African American women we are under surveillance to make sure that they do not pose a “threat” to the status quo.

The remainder of this section describes the requirements of the professorate metaphorically to describe the roles of African American women as maids of academe in the following way: teaching as childcare activities, research and scholarship as field work, and service as housework, cooking, and other duties. In each of these roles many African American women faculty at PWIs find themselves in institutions with a plantation mentality in which getting white academic professional to listen to their voices is a particular challenge (Alfred 2001a, b).

Teaching: Child Care Activities

Childcare activities involve providing the child (student) with a knowledge base that prepares them academically, vocationally, and socially to function in society. African American women are frequently those who teach courses on diversity, as well as have a heavy teaching load. Not only do they have to bathe, feed, and dress the children, but they have to play with them and show them how to use new toys (i.e., developing and infusing diversity into the curriculum). It is as if African Americans are the only ones who can do this. Just as parenting experts say that fathers as well as mothers are significant to child rearing and a child’s development, Banks (1993) stressed that diversity is the domain of all qualified faculty. Therefore, African American women should not be the only or primary nurturers of the “child”—diversity. In addition, they should not have a disproportionate responsibility for teaching.

An important part of teaching includes mentoring of students. African American women faculty members often find that not only are they mentoring African American students but other students of color, female students, and sexual minority students as well. It is as if African American women faculty members are care providers for groups that are designated as special interest groups. Clearly, each of these groups holds a marginalized position and the role of “other” in society and in the academy. African American women faculty engages in “academic midwifery” in which they assist students in giving birth to new ideas and cognitive hierarchies (Brown 2000, p. 79).

Research and Scholarship: Field Work

Fieldwork is essential to crop production (scholarship and publications), which provides food for the entire plantation (university) and the general community (academy). Without the activities of fieldwork, the plantation does not have the necessary tools to support other areas of the plantation that results in a rich harvest (national recognition and acclaim). Research institutions (overwhelmingly PWIs) employ the largest number of full-time faculty members, conduct the most influential research, and produce the majority of doctorates (Trower and Chait 2002). Research and scholarship are two areas, which represent the hallmark of tenure and promotion at research universities, as well as propel them to national prominence. Marginalizing African American women faculty and/or the devaluing of their research portray them as not being major players and contributors to the institution. The literature documents a pervasive theme that the qualifications and contributions of faculty of color are devalued or undervalued and that this racial bias carries over to the tenure and promotion process (Gregory 1999; Gulam 2004; Turner and Myers 2000; Villapando and Bernal 2002). In fact, promotion and tenure committees often do not weigh the “hidden workload” of especially burdensome advising responsibilities, service, and committee work on African American women faculty (Brown 2000). The unwritten rules of the academy often affect African American women faculty differently (Thompson and Louque 2005).

Service: Housework, Cooking, and Other Duties

Housework and cooking are essential to the sustainability of the house (university). Of all of the duties in academe, service is the most beneficial to the university because it is a category in which faculty members provide an inordinate amount of work. In many ways the service category gives universities the lead way to keep adding responsibilities to the workload of faculty. Although at major research universities, service is suppose to be a minor role because establishing a research agenda and publication record is paramount, African American women are generally over-extended in committee work and other service requirements (Jarmon 2001). In fact, African American faculty members (and other faculty of color) have different demands placed on their time and energy than what is expected from white faculty members (Turner and Myers 2000). Ironically, African American women faculty members are not only the “maids of academe” but the “work mules” (i.e., carrying a heavy load) as well. Brown (2000) referred to the over extension of African American faculty as the “mournful wail” (i.e., others making demands on our time and energy) of African American faculty, which doubles if not triples their workload and channels them into a series of activities not formally recognized or rewarded by the university structure (p. 75).

Psychosocial Adjustment and Coping

African American faculty members tend to experience greater amount of stress in the areas of promotion concerns (e.g., review and promotion process, research and publishing demands, subtle discrimination), time constraints (e.g., lack of personal time, time pressures, teaching load), home responsibilities (e.g., household responsibilities, child care, children’s problems, marital conflict), and governance activities (e.g., faculty meetings, committee work, consulting with colleagues). For African American women faculty stress in these areas is associated with the work experience as well as being a woman (Thompson and Dey 1998). African American women frequently experience stress because of their efforts to do twice as much and to accomplish tasks better than expected. In addition to the external and societal forces they wrestle with, there is the reliance of the African American community on our ability to juggle multiple commitments (Wenniger and Conroy 2001). A typical African American woman is a very complicated conglomerate of many roles (i.e., daughter; sister, both as an actual sibling and part of the black sisterhood; wife; partner; mother; community activist; church leader; homemaker; so forth) (Wolfman 1997). One viable explanation of their ability to adjust to and cope with numerous facets of their professional and personal lives is that of resilience. Resilience theory focuses on the fact that individuals with multiple risk factors in their lives are able to triumph over their challenges and do well in spite of the predictions of experts. For African American women resilience is the ability to multi-task, to solve problems, to have a feeling of responsibility and able to make a difference (i.e., internal locus of control), and the use of spiritual beliefs as a support. To truly have resilience requires confidence and hard work, as demonstrated by African American women faculty.

African American women seem to have a passion for teaching and university and community service, which forces them to work 14–16 h/day and to still try to publish and secure grant dollars (Jarmon 2001; Turner and Myers 2000). Although admirable, they often excel at achieving these activities at a high cost. For example, African American women faculty may exhibit hypertension, heart disease, obesity, impaired immune function, high levels of depression, anxiety, and stressors related to the demands of academic life and the multi-marginality of being underrepresented by race, a scholarly agenda, and the larger academic and social communities (Bradley 2005; Jones 2001; Neal-Barnett 2003; Thompson and Dey 1998). Dissatisfaction at work can create stress and stress can result in health problems (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health 2005), which cost US industry over $300 billion annually (American Institute of Stress 2005). According to Wolfman, “it may be that African American women demand much of themselves, setting their own standards of excellence, which they then must meet. This often creates problems with coworkers, who may not share these standards or understand the necessity of them” (pp. 163–164).

Being African American women faculty at PWIs creates extreme amounts of pressure because of having to deal with alienation, racism, and sexism. According to DeJesus and Rice (2002), “while the literal twine of the noose of racism that chocked our throats is relatively obsolete, the figurative rope continues to cut the breath of our psychological well-being” (p. 52). African American women faculty members are continuously confronted with the challenge to prove that they do not have their job because of affirmative action, tokenism, or “opportunity hire.” In addition, African American faculty members have an additional layer of responsibility that their white colleagues are not naturally called upon to do (e.g., be the healer of black people on campus, be the expert on everything black, expected to handle minority affairs). Padilla (1994) referred to this expectation of handling minority issues as “cultural taxation.” Cultural taxation is “the obligation to show good citizenship toward the institution by serving its needs for ethnic representation on committees, or to demonstrate knowledge and commitment to a cultural group, which may even bring accolades to the institution but which is not usually rewarded by the institution on whose behalf the service was performed” (p. 26).

Frequently, African American faculty participate in university meeting in which they are the only one or one of only a few. According to Wenniger and Conroy (2001), “African American women are at once more visible and equally isolated due to racial and gender differences. The token woman often finds herself in situations where she is made aware of her unique status as the only African American female present, yet feels compelled to behave as though this difference did not exist” (p. 47). So, the question becomes how do African American faculty in general and African American women faculty in particular adjust to and cope with the psychosocial issues of being at PWIs, especially those with hostile environments, without becoming psychological casualties? The answer to this question is not simple and it is linked to cultural taxation, teaching load, research interests, and cultural sovereignty as previously described. Furthermore, any discussion of psychosocial adjustment of African American women must connect political injustice with psychological pain. Although political, legal, and social efforts have ushered in changes in the structure of racism and sexism in the US, “we still live within a white supremacist capitalist patriarchal society that must attack and assault the psyches of black people (and other people of color) to perpetuate and maintain itself” (Hooks 1995, p. 144). Below are descriptions of several ways in which African American women respond to stress. These examples are not intended to be an exhaustive list.

African American faculty members cope with psychosocial stressors and positionalities (social location) of being at PWIs in several ways: reliance on the family and the community; through achievement; a belief in hard work, cooperation, responsibility, and ancestral wisdom; and religious beliefs and rituals including prayer (Shorter-Gooden 2004; Utsey et al. 2000). In addition, many African American women faculty either knowingly or unknowingly utilize the seven principles of Kwanzaa: umoja (unity), kujichagulia (self-determination), ujima (collective work and responsibility), ujamaa (cooperative economics), nia (purpose), kuumba (creativity), and imani (faith) (Riley 1995) to sustain their psychological and social balance. For African American women each of these principles reflects a cultural responsibility to achieve success both as an individual and at a communal level.

African American women faculty members also cope with stress through networking. They talk with each other about their experiences and challenges. Then, they strategize about ways to respond and how to examine the pros and cons of various situations. In many ways networking is therapeutic and African American women faculty members act as “kitchen divas” (Flint and Ashing-Giwa 2005) for each other in which they gather support and strengthen each other. Frequently, as part of conversation the question of why do they stay at PWIs is discussed. For many of them it is because they want to make a difference and leave a legacy for other African Americans and women. Just as many of the fore runners of the Civil Rights movement did not benefit directly from their struggle, those who followed them did. In essence, African American women’s will to resist deprivilege consequences allows them to persist.

Finally, African American women faculty members use their connection with spirituality and religion to cope with many adversities of life. Throughout our history in America African American women have relied on spirituality to sustain them (Hooks 1993). Overwhelmingly, African Americans do not make a distinction between spirituality and religion. Many of the spiritual and religious practices of African Americans involve indigenous approaches (Harley 2005a). African Americans’ belief in and reliance on a higher power (i.e., God) that will help you work it out is chronicled from slavery to the present. The “legacy of bearing up” under adverse circumstances is reflected in Negro spiritual and gospel hymns with titles like “Nobody Knows the Troubles I’ve Seen,” and “Deep River, My Home is Over Jordan” (Poussaint and Alexander 2000). According to Poussaint and Alexander, qualities assigned to African Americans: (a) a corresponding inner strength as part of blacks’ fundamental psychological makeup, (b) the idea of strength is required to endure the difficulties of life on earth has been central to black culture, and psychological, spiritual, and physical endurance, and (c) the entrenchment of a self-image in which African Americans must be capable of dealing with any stress that comes along have become both self-perceived assets and viewed by others as traits that justify a belief and behavior that African Americans “willingly” accept a lower-caste status in society.

Emphasis on the “psychospiritual” goes beyond the mind and body, while binding together cognitive, affective, and behavioral realms of existence into an integrated whole (Lee and Armstrong 1995). Given African American women’s strong ties to religion, it is logical to conclude that it would affect their sense of psychological well-being. In many ways, the Black church is a therapeutic asylum and agent for them (Dillard and Smith 2005; Harley 2005b). Internally, African American women faculty members at PWIs are constantly negotiating a defense against an attack on their psyche, intellectual abilities, and cultural capital. In essence, they are reframing their professional experiences by incorporating and owning their self-worth through “a philosophy of work that emphasizes commitment to any task” and “the importance of working with integrity irrespective of the task” (Hooks 1993, p. 42).

Physical and Spiritual Consequences

Although most women experience forms of sexism, racist attitudes lead to a more harmful form for African American women (Jones and Shorter-Gooden 2003). Having the ability to cope can either serve to enhance or diminish the reactions to racism. That is, maladaptive coping responses may trigger physiological stress responses and adaptive ones can alleviate stress responses (Clark et al. 1999). Understanding the toll of racism and race fatigue on the physical health and spiritual well being of African American women require examination of multiple indices including self-value and self-discovery, post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (or posttraumatic slavery syndrome as referred to by Poussaint and Alexander 2000), being a numerical minority, the ideology of assimilation, and patterns of socialization (Lawson and Pillai 1999).

In a study of sources of stress for African American college and university faculty Thompson and Dey (1998) found that: (a) the more of the particular type of stress experienced, the less satisfied faculty are, (b) although not all stress is universally related in a negative direction to satisfaction, this is the predominant trend, and (c) stress is consistently associated with lower levels of satisfaction. In fact, African American women when compared to African American men faculty experience greater vulnerability to certain areas of stress (previously mentioned). Explanations for these outcomes indicate that women have lower professional status; men are more likely to have supportive home networks, which allow them greater opportunities to become part of the larger community social networks; women spend more time on household chores, which is related to time constraints; and faculty who have higher salaries (who are likely to be men) experience less stress related to home responsibilities (Thompson and Dey 1998).

One additional area that influences African American women faculty is marital status. Whereas many white feminists portray the home as a major source of women’s oppression, many African American women find home and family affirming of their humanity and a refuge from the hostility of the larger society (Dugger 1996; Thompson and Dey 1998). According to Thompson and Dey, because many single African American women faculty are required to relocate to secure a job, the affirmation of home and family are not always readily available, which frequently heightens their marginality. In many ways “the stress related to meeting regular faculty productivity demands while also juggling role expectation as outsiders in a white, male-dominated profession are usually not anticipated or acknowledged by others” further increases taxation of African American women’s physical and spiritual well being (Thompson and Dey 1998, p. 340).

Legal Issues

Laws and policies prohibiting discrimination against individuals on the basis of race and gender (and other demographic characteristics) are present in the United States (e.g., Civil Rights Act, Affirmative Action); the existence of which signifies the presence of unfair and unequal opportunities against racial minorities. Nevertheless, discrimination against African American women at PWIs persists. A statement made by Weinberg (1977) 30-years ago reflects the historical and current legacy of white privilege in the academy. Weinberg stated:

Since its earliest beginnings, the American public school system has been deeply committed to the maintenance of racial and ethnic barriers. Higher education, both public and private, shared this outlook. Philosophers of the common schools remained silent about the education of minority children... White educators profited from the enforced absence of black and other minority competitors for jobs. Planned deprivation became a norm of educational practice (p. 1).

In a very direct manner this statement addresses a quota system and select hires, which easily translate into “only whites need apply,” and practices that have been sanctioned by custom and law. A history of exclusionary employment of African American faculty at PWIs has created bastions of segregation, marginalization, and academic apartheid.

A review of the current status of African American women faculty at PWIs reveals that in the past 30-years no significant gains have been made or no major changes have occurred. Frequently, when an African American faculty leaves a PWI, he or she may be replaced with another African American, but no increase in number of African American faculty occurs. That is, it is not uncommon for PWIs to have a “zero” net gain in the number of African American faculty. Furthermore, affirmative action efforts continue to be met with resistance.

Numerous lawsuits have been filed by African American faculty against PWIs related to discrimination (e.g., Clark v. Claremont University and Graduate School), and issues of underrepresentation (e.g., Adams v. Richardson). Frequently, legal cases portray African Americans as seeking something in which they are not qualified. Moreover, the entire legal process adds to the stressors (physical, emotional, financial) experienced by African American faculty members. African American faculty often may find that their counterparts, students, staff, and administrators may engage in inflammatory comments and derogatory behavior against them. The comments of these individuals are increasingly cloaked in the First Amendment (Wenniger and Conroy 2001).

Recommendations and Strategies to Improve Academic Culture and Climate

The culture and climate at many PWIs is one of hostility toward African Americans in general and African American females in particularly. The remainder of this section includes recommendations for improving academic culture and climate for African American women faculty at PWIs, and empowerment strategies for African American women faculty. The current era of higher education strategic planning signifies both a foundational and philosophical approach for improving and sustaining institutional accomplishments. As part of the vision for the future, many PWIs have identified diversity in faculty and the student body as a commitment. In that vain, the following additional recommendations are offered.

Thompson and Louque (2005) suggested that any attempt of leaders in the academy to best retain African American faculty is to start with the “bright side of the academy” (p. 154), which includes looking at three questions. The first question is to determine which of their professional responsibilities are most important to African American women faculty. Second, examine what are the most rewarding aspects of “life” in the academy for them. Third, compile recommendations from African American women faculty about how the academy can increase their job satisfaction. A review of several key studies, which examine pertinent issues of African American faculty at PWI reveal that teaching (47%) emerged as the most frequently cited most important professional responsibility, followed by research (27%), mentoring (15%), writing (11%), presenting (7%), and community service (6%) (Thompson and Louque 2005). Turner and Myers (2000) found that African American faculty stressed teaching and interactions with students as the most satisfying aspects of their work lives, followed by supportive administrative leadership, a sense of personal accomplishment, mentoring relationships, collegiality, and commitment to community and relating to other faculty of color.

In response to the second question of what matters to African American faculty, Thompson and Louque (2005) found that the most rewarding aspects of life in the academy included mentoring students of color (57%), their research (52%), community service (41%), course preparation (38%), interpersonal relations with colleagues (38%), and support from other African Americans (33%). Overwhelmingly, African American faculty value teaching, research, mentoring of students, service, and collegiality. What they value is in line with institutional priorities and yet their contributions in these areas continue to be devalued.

Recommendations from African American faculty focused on improving the campus climate (increase recruitment, improve racial climate, provide diversity training for all constituents), increasing support (mentoring and value their input and contributions), modifying professional duties (reduce teaching load, provide assistance with research, reduce committee workload), providing compensation and other incentives (better salaries, equitable pay), improving tenure and promotion practices, respecting community service, and respecting African American faculty’s work with African American students (Thompson and Louque 2005). Similar strategies were suggested by African American faculty in the study by Turner and Myers (2000) in which the most frequently suggested recommendations include networking, mentoring, and better support for research and publication.

The results of these studies are consistent with earlier studies (Davis 1985; Exum et al. 1984; Gregory 1999; McKay 1983; Menges and Exum 1983; Pruitt 1982; Wyche and Graves 1992) and more recent studies (Bradley 2005; Turner 2002; Weems 2003; cite) that examined common barriers to success and achievement and personal lifestyle choices of African American women faculty in academe. The reoccurring themes throughout various studies demonstrate that African American women faculty have been and continue to be on the receiving end of disproportionality, marginality, exclusionary practice, and a lack of diversity benchmarks at PWIs.

Other recommendations were offered by Weems (2003) and include the following:

-

1.

Academic units would make it clear, in writing at the time of hiring, all commitments regarding a new faculty member’s teaching, research, and service obligations... Expectations for obtaining tenure would be clearly explained. For new minority faculty members, this would include a sensitivity to and value of refereed ethnic or gender-based journals (emphasis added).

-

2.

Departments would create a systematic means for integrating new faculty into the department... Each department would have a mentoring program in which the new faculty member has some voice in choosing his/her mentor. For a new minority faculty member, it would be imperative that his/her mentor be sensitive to the issues that minority faculty face (emphasis added).

-

3.

Departments would conduct annual review of all junior faculty in which the faculty member’s progress toward promotion and tenure is explained. An appeals process should be included... For minority faculty members being reviewed, this process would be sensitive to the value of scholarship arising from a faculty member’s ethnicity or gender (emphasis added).

-

4.

Central administration would conduct a thorough training program for all new department chairs/head, and associate chairs, to promote the goal of a more diverse faculty... One of the primary duties of the chair/associate chair/head, in reference to promoting and retaining a diverse faculty, would be to sensitize support staff that the needs of minority faculty are equally important (emphasis added).

-

5.

Department chairs would conduct exit interviews with all departing faculty members to ascertain any changes the department might make to improve retention of faculty it wishes to keep. Exit interviews of departing minority faculty would be especially detailed (emphasis added) (p. 108).

These recommendations will improve not only the work environment and experiences of African American women, but of all faculty members. While each of the recommendations stated above apply to all faculty members, for African Americans, other faculty of color, and women faculty implementing these strategies can attest to an institution’s legitimate commitment to diversity. To achieve a diverse institutional setting a high level of commitment by people throughout the institution is essential. Proactive efforts should be linked to measures of accountability in which departments submit annual reports on efforts, and an external review process should be developed to monitor institutional progress. According to Turner and Myers (2000), the responsibility of monitoring the implementation and progress of recommendations should occur at the Provost level. In addition, college deans should be leaders of diversity. According to Harvey (2004), a dean’s message must be compelling and his or her actions proactive. To that end, Harvey recommended the following lessons for deans:

-

1.

Just because a dean articulates a message, even an important one, doesn’t mean that the faculty ‘get it.’ When the message is about faculty diversity, without active management, the customary habits and practices are likely to prevail.

-

2.

Find all allies in the faculty so that they can carry the diversity banner, not just in formal searches, but in all of the departmental formal and informal discussions that occur—the kinds of discussions that deans aren’t invited to participate in, and usually don’t even know are taking place.

-

3.

Shut it down: When a search has been conducted and it turns out that diversity considerations have been ignored or overlooked, close the search and start again.

-

4.

Know whom to trust: ...Not everyone stands opposed to having more faculty of color among their ranks.

-

5.

Get some stars: It’s wonderful to have young faculty members of color who are filled with potential and promise, but it’s even better to have some seasoned, experienced, and accomplished senior faculty who can and will address issues of inequity and injustice, and not have to worry whether doing so will result in an unfavorable review of their performance and/or the enmity of their colleagues (pp. 296–305).

Many institutions focus primarily on recruiting African American faculty and fail to have a plan for retention. It is as if once African Americans faculty members arrive on campus, university administrators feel as if they have accomplished their goal. Even when institutions set goals numerically for hiring African American faculty these goals are disproportionately low and with an unrealistic timetable. Clearly, more attention needs to be given to effectively positioning PWI to transition from what Franklin (1989) described as “a homogeneous past to a more heterogeneous future” (p. 4A).

Survival of African American women in the academy is contingent upon many variables, but none as important as their own self-worth, self-reliance, and generating support networks inside and outside the university setting (Alfred 2001b; Atwater 1995). African American women realize that resistance to diversity and arrogance against inclusion are the hallmarks of the culture at PWIs. Nevertheless, their presence and voices are both necessary and required to bring about change. Below are strategies for use by African American women faculty.

-

1.

Understanding that self-validation will sometimes be the only source of acknowledgement for accomplishments (Phelps 1995). African American women may find that if they do not sing their own praises, it may not happen. The best practice is not to be modest about their successes.

-

2.

Recognizing they cannot be all things to all people. African American women must shake-off the responsibility trap and move from “maid status” to shared governance. If their contributions are indeed valued by the university, they cannot continue to be the go-to-person for diversity issues and excluded from other organizational participation. In addition, they cannot continue to be overloaded and over extended with representation responsibilities on various committees.

-

3.

Maintaining mental, physical, and spiritual health (Jones 2001; Neal-Barnett 2003; Phelps 1995). African American women must carve out time for themselves away from the academy. Engaging in activities and in environments that are conductive to their interests and strengths provide validation of their value, as well as balance to their lives.

-

4.

Recognizing institutional culture. African American women need to recognize the culture (i.e., norms) of the institution and that PWIs tend to operate according to norms rather than rules (Phelps 1995). In fact, the academic environment is often “chilly,” hostile and indifferent toward African American women faculty and administrators (Alfred 2001b; Benjamin 1997; Smith 1999; Turner 2002).

African American women faculty must be knowledgeable and aware of the politics of higher education—“politics that... can become just as pernicious as those of the most ruthless and cutthroat organizations in US society” (Thompson and Louque 2005, p. 151). Just as a critique of the negative side of PWIs is done, an inventory of what is positive and where to find opportunities for growth for the institution is also warranted. Turner and Myers (2000) found that African American faculty members stay at PWIs because of professional responsibilities (e.g., teaching, research, mentoring, writing, presenting, community service). In addition, faculty saw their work as rewarding with the most rewarding aspects of life in the academy as mentoring students of color, research, community service work, course preparation, and interpersonal relations with colleagues. Each of these factors shape the professorate lifespan of African American women faculty.

Conclusion

Pursuing a career in academia is a rigorous process with explicit and implicit requirements. African American women faculty frequently face obstacles not experienced by their white colleagues. The literature suggests that for many African American women faculty at PWIs the positives are greatly overshadowed by the negatives (Back 2004; Bradley 2005; Harley 2001; McKay 1997; Turner and Myers 2000). In addition, African American women maintain high levels of community involvement with local and national publics, mentoring responsibilities, disproportionate service assignments, heavy teaching loads, and active research and grant productivity. Writing about pertinent issues and concerns of African American women faculty at PWIs is one way to find solutions and pass them on. However, strategies are meaningless unless they are implemented. For African American women the task is to continue to work as change agents without burnout, physical illness, psychological stress, and spiritual bankruptcy.

References

Alfred, M. V. (2001a). Success in the ivory tower: Lessons from Black tenured female faculty at a major research university. In R. O. Mabokela, & A. L. Green (Eds.), Sister of the academy: Emergent black women scholars in higher education (pp. 57–79). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Alfred, M. (2001b). Reconceptualizing marginality from the margins: Perspectives of African American tenured female faculty at a white research university. The Western Journal of Black Studies, 25, 1–11.

Atwater, M. M. (1995). African American female faculty at predominately white research universities: Routes to success and empowerment. Innovative Higher Education, 19, 237–240.

American Institute of Stress (2005). Job stress. Retrieved January 22, 2007, from http://www.stress.org.

Back, L. (2004). Ivory towers? The academy and racism. In I. Law, D. Phillips, & L. Turney (Eds.), Institutional racism in higher education (pp. 1–6). Sterling, VA: Trentham Books.

Banks, J. (1993). The cannon debate, knowledge construction, and multicultural education. Educational Researcher, 22, 4–14.

Benjamin, L. (Ed.) (1997). Black women in the academy: Promises and perils. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Bradley, C. (2005). The career experiences of African American women faculty: Implications for counselor education programs. College Student Journal, 39, 518–527.

Brown, M. C. (2000). Involvement with students: How much can I give? In M. Garcia (Ed.), Succeeding in an academic career: A guide for faculty of color (pp. 71–88). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Carter, D., Pearson, C., & Shavlik, D. (1988). Double jeopardy: Women of color in higher education. Educational Record, 68/69, 98–103.

Clark, R., Anderson, N. B., Clark, V. R., & Williams, D. R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54, 805–816.

Collins, A. C. (2001). Black women in the academy: An historical overview. In R. O. Mabokela, & A. L. Green (Eds.), Sisters of the academy: Emergent black women scholars in higher education (pp. 29–41). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Cosby, C. O., & Poussaint, R. (Eds.) (2004). A wealth of wisdom: Legendary African American elders speak. New York: Atria Books.

Cresswell, T. (1996). In place/out of place: Geography, ideology, and transgression. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Davis, L. (1985). Black and white social work faculty: Perceptions of respects, satisfaction, and job permanence. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 12, 79–94.

Dillard, J. M., & Smith, B. B. (2005). African Americans’ spirituality and religion in counseling and psychotherapy. In D. A. Harley, & J. M. Dillard (Eds.), Contemporary mental health issues among African Americans (pp. 279–291). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Dugger, K. (1996). Social location and gender-role attitudes: A comparison of Black and White women. In E. Ngan-Linf chow, D. Wilkinson, & M. Baca Zinn (Eds.), Race, class and gender: Common bonds, different voices. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Exum, W., Menges, B., Watkins, B., & Berglund, P. (1984). Making it at the top: Women and minority faculty in the academic labor market. American Behavioral Scientist, 27, 301–324.

Flint, J. R., & Ashing-Giwa, K. (2005). Kitchen divas: Breast cancer risk reduction for black women. Retrieved on January 22, 2007 from http://www.cbcrp.org/research/PageGrant.asp?grant_id=4071.

Franklin, J. H. (1989). Race and history: Selected essays (1938–1988). Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Gates, H. L., & West, C. (2000). The African American century: How Black Americans have shaped our country. New York: The Free Press.

Gregory, S. T. (1999). Black women in the academy: The secrets to success and achievement. New York: University Press of America.

Gulam, W. A. (2004). Black and white paradigms in higher education. In I. Law, D. Phillips, & L. Turney (Eds.), Institutional racism in higher education (pp. 7–13). Sterling, VA: Trentham Books.

Harley, D. A. (2001). In a different voice: An African American woman’s experiences in the rehabilitation and higher education realm. Rehabilitation Education, 15, 37–45.

Harley, D. A. (2005a). African Americans and indigenous counseling. In D. A. Harley, & J. M. Dillard (Eds.), Contemporary mental health issues among African Americans (pp. 293–306). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Harley, D. A. (2005b). The Black church: A strength-based approach. In D. A. Harley, & J. M. Dillard (Eds.), Contemporary mental health issues among African Americans (pp. 191–204). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Harvey, W. B. (2004). Deans as diversity leaders. In F. W. Hale, Jr. (Ed.), What makes racial diversity work in higher education: Academic leaders present successful policies and strategies (pp. 292–306). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Hooks, B. (1992). Representations of whiteness, black looks: Race and representation. Boston: South End Press.

Hooks, B. (1993). Sisters of the yam. Black women and self-recovery. Boston: South End Press.

Hooks, B. (1995). Killing rage: Ending racism. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Hooks, B. (2001). Salvation: Black people and love. New York: Harper Collins.

Jarmon, B. (2001). Unwritten rules of the game. In R. O. Mabokela, & A. L. Green (Eds.), Sisters of the academy: Emergent black women scholars in higher education (pp. 175–181). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Jones, L. (Ed.) (2001). Retaining African Americans in higher education: Challenging paradigms for retaining students, faculty, and administrators. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Jones, C., & Shorter-Gooden, K. (2003). Shifting: The double lives of Black women in America. New York: Harper Collins.

Kawewe, S. M. (1997). Black women in diverse academic settings: Gender and racial crimes of commission and omission in academia. In L. Benjamin (Ed.), Black women in the academy: Promises and perils (pp. 263–269). Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Lawson, E. J., & Pillai, V. (1999). The persistence of racism in America’s cultural diversity. In L. L. Naylor (Ed.), Problems and issues of diversity in the United States (pp. 67–86). Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

Lee, C. C., & Armstrong, K. L. (1995). Indigenous models of mental health intervention: Lessons from traditional healers. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & C. M. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 441–456). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

McKay, N. (1983). Black woman professor—White university. Women’s Studies International Forum, 6, 143–147.

McKay, N. (1997). A troubled peace: Black women in the halls of the white academy. In L. Benjamin (Ed.), Black women in the academy: Promises and perils (pp. 11–222). Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Menges, R., & Exum, W. (1983). Barriers to the progress of women and minority faculty. Journal of Higher Education, 54, 123–144.

Mills, C. (1997). The racial contract. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2005). Stress. Retrieved January 22, 2007, from http://www.cdc.gov/niash/stresswk.html.

Neal-Barnett, A. (2003). Stress, anxiety, and strong black women. Soothe your nerves: The black woman’s guide to understanding and overcoming anxiety, panic, and fear. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Padilla, A. M. (1994). Ethnic minority scholars, research, and mentoring: Current and future issues. Educational Researcher, 23, 24–27.

Poussaint, A. F., & Alexander, A. (2000). Lay my burden Down: Unraveling suicide and the mental health crisis among African Americans. Boston: Beacon Press.

Pruitt, A. (1982). Black employees in traditional white institutions in the ‘Adams’ states, 1975–1977. New York: American Education Research Association.

Purwar, N. (2004). Fish in and out of water: A theoretical framework for race and the space of academia. In I. Law, D. Phillips, & L. Taurney (Eds.), Institutional racism in higher education (pp. 49–58). Sterling, VA: Trentham Books.

Rangasamy, J. (2004). Understanding institutional racism: Reflections from linguistic anthropology. In I. Law, D. Phillips, & L. Taurney (Eds.), Institutional racism in higher education (pp. 27–34). Sterling, VA: Trentham Books.

Riley, D. W. (1995). The complete Kwanzaa: Celebrating our cultural harvest. New York: Harper Collins.

Shorter-Gooden, K. (2004). Multiple resistance strategies: How African American women cope with racism and sexism. Journal of Black Psychology, 30, 406–425.

Smith, P. (1999). Teaching the retrenchment generation: When Sapphire meets Socrates at the intersection of race, gender, and authority. William and Mary Journal of Women and Law, 53, 1–141.

Thompson, C. J., & Dey, E. L. (1998). Pushed to the margins: Sources of stress for African American college and university faculty. The Journal of Higher Education, 69, 324–345.

Thompson, G. L., & Louque, A. C. (2005). Exposing the “culture of arrogance” in the academy. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Trower, C. A., & Chait, R. P. (2002). Faculty diversity: Too little too long. Harvard Magazine. Retrieved November 8, 2006 from http://www.harvard-magazine.com.

Turner, C. S. V. (2002). Women of color in academe: Living with multiple marginality. The Journal of Higher Education, 73, 74–93.

Turner, C. S. V., & Myers, S. L. (2000). Faculty of color in academe: Bittersweet success. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Utsey, S. O., Adams, E. P., & Bolden, M. (2000). Development and initial validation of the Africultural Coping Systems Inventory. Journal of Black Psychology, 6, 194–215.

Villapando, O., & Bernal, D. D. (2002). A critical race theory analysis of barriers that impede the success of faculty of color. In W. A. Smith, P. G. Altbach, & K. Lomotey (Eds.), The racial crisis in American higher education (pp. 243–269). New York: State University of New York Press.

Washington, D. E. (1997). Another voice from the wilderness. In L. Benjamin (Ed.), Black women in the academy: Promises and perils (pp. 270–278). Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Weems, R. E. (2003). The incorporation of Black faculty at predominantly white institutions: A historical and contemporary perspective. Journal of Black Studies, 34, 101–111.

Weinberg, M. (1977). A chance to learn: The history of race and education in the United States. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wenniger, M. D., & Conroy, M. H. (2001). Gender equity or bust: On the road to campus leadership with women in higher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

West, C. (1993). Race matters. New York: Vintage Books.

Williams, L. D. (2001). Coming to terms with being a young, black female academic in US higher education. In R. O. Mabokela, & A. L. Green (Eds.), Sisters of the academy: Emergent black women scholars in higher education (pp. 93–104). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Wolfman, B. R. (1997). Light as from a beacon: African American women administrators in the academy. In L. Benjamin (Ed.), Black women in the academy: Promises and perils (pp. 158–167). Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Wyche, K., & Graves, S. (1992). Minority women in academia: Access and barriers to professional participation. Psychology Of Women Quarterly, 16, 429–437.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harley, D.A. Maids of Academe: African American Women Faculty at Predominately White Institutions. J Afr Am St 12, 19–36 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-007-9030-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-007-9030-5