Abstract

The present research examined how a preference for influencing the mate choice of one’s offspring is associated with opposition to out-group mating among parents from three ethnic groups in the Mexican state of Oaxaca: mestizos (people of mixed descent, n = 103), indigenous Mixtecs (n = 65), and blacks (n = 35). Nearly all of the men in this study were farmworkers or fishermen. Overall, the level of preferred parental influence on mate choice was higher than in Western populations, but lower than in Asian populations. Only among the Mixtecs were fathers more in favor of parental influence on the mate choice of children than mothers were. As predicted, opposition to out-group mating was an important predictor of preferred parental influence on mate choice, more so among fathers than among mothers, especially in the mestizo group—the group with the highest status. In addition, women, and especially mestizo women, expressed more opposition to out-group mating than men did.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In contemporary Western culture, people are free to choose their own mates, which is in stark contrast to mate choice in many other cultures and, indeed, even in contrast to how mate choice has occurred throughout most of human history. More often than not, parents have exerted and continue to exert a strong influence on the mate choice of their offspring (Murstein 1974). In fact, in many parts of the world what is commonly known as arranged marriage was—and sometimes still is—the predominant form of marriage (Reiss 1980). The custom of arranged marriage is still practiced in India and China (Gautam 2002; Madathil and Benshoff 2008; Pimentel 2000; Riley 1994), and a particularly extreme form of this type of marriage, in which parents force their children into a marriage at a young age, is widespread in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa (United Nations Population Fund 2005). Even in Western societies, arranged marriage continues to occur among many immigrant communities. For example, near the end of the twentieth century, about half of the marriages of Indian immigrants in the United States were arranged (Menon 1989). In a study among second-generation South Asian immigrants living in North America, about a quarter of the participants indicated that their parents would likely arrange their marriages (Talbani and Hasanali 2000). Even when not directly arranging the marriages of their children, parents in these immigrant groups often attempt to control their children’s mate choice to a considerable extent, and second-generation immigrants indicate that conflicts with their parents over dating and marriage are common (Das Gupta 1997; Dugsin 2001; Hynie et al. 2006; Lalonde et al. 2004).

Even in cultural groups and societies where the norm is for children to choose their own romantic partners and form “love-based marriages,” parents may still attempt to exert control over their children’s mate choices. Parents may accomplish this by controlling their child’s social networks, setting them up on dates, expressing opinions regarding the type of person their child ought to marry, and even threatening to withdraw economic support should their child marry outside their social class or ethnic group (e.g., Das Gupta 1997; Faulkner and Schaller 2007; Wight et al. 2006). Other common means that parents might use to influence their child’s mate choice include expressing disapproval of their child’s romantic partners and setting restrictions on their child’s social and romantic behaviors. A study by Perilloux et al. (2008) of parents and children living in the United States investigated gender differences in these domains. Parents reported that it was more important to approve of their daughter’s mate choice than a son’s, but children of both sexes reported that they had experienced parental disapproval of their mate choices (59% of daughters and 30% of sons). The same study also found that 60% of daughters and 36% of sons reported having to adhere to a curfew, and parents tended to restrict daughters more so than sons from engaging in behaviors that might lead to sexual intercourse.

The fact that parental control over mate choice also occurs in places such as the United States, where free mate choice has long been a culturally favored pattern (Reiss 1980), suggests that the inclination to influence the mate choice of one’s children is a basic human drive. This assumption is supported by recent data presented by Apostolou (2007) covering 190 hunter-gatherer societies—often used as a proxy for the conditions under which modern humans evolved. His data showed that in roughly 70% of the societies, marriages were primarily arranged by the parents; only in 4% of the societies was courtship—where children ultimately decide their partners—the primary form of selecting a spouse. There is indeed evidence from many indigenous societies that arranged marriages were common before the advent of agriculture. For example, among the !Kung of the Kalahari Desert, marriages are usually arranged by parents and other close relatives (Shostak 1983), and in a community of Australian aboriginals, marriages are also predominantly arranged (Burbank 1995).

Preserving and Strengthening the In-group

In this article, we argue that, overall, a major reason for parents wanting to control the mate choice of their offspring is that they want to maintain the homogeneity and cohesion of the in-group. This notion is in line with the observation that relatively high levels of parental control over mate choice are found to be more common in cultures where individuals are highly dependent on the in-group—i.e., collectivistic cultures. According to Hofstede (1980), collectivistic cultures are characterized by values such as group solidarity, duties and obligations, and group decisions. A central characteristic of such cultures is the emphasis on loyalty to one’s family and on giving in to the wishes of one’s family. Particularly collectivist cultures such as China, India, and Japan have historically been characterized by arranged marriages (e.g., Applbaum 1995; Mitchell 1970; Riley 1994; Xie and Combs 1996). In contrast, romantic love—which reflects individuals’ feelings as a basis for the choice of a spouse—is considered a more important basis for marriage in more individualistic cultures—i.e., cultures characterized by values such as autonomy, right to privacy, and pleasure seeking (e.g., Levine et al. 1995). Free mate choice appears to have existed in the United States (one of the most individualistic cultures in the world) since the time of the first settlers (Furstenberg 1966; Reiss 1980). In line with the foregoing, Buunk et al. (2010) found a strong correlation across countries between the perceived level of parental control over mate choice in the culture and the independently assessed level of collectivism of the culture. In an additional study, they found that, compared with Dutch students and Canadian students with a Western background, individuals from cultures with collectivistic norms (young people from Kurdistan [Iraq] and Canadian students with an East Asian background) favored relatively high levels of parental influence on mate choice.

To foster and preserve the homogeneity and cohesion of the in-group, a major concern of parents is that the mates of their children have the same social, ethnic, and religious background. Marriages to people with different backgrounds are in many cases considered something to be circumvented, and in some cultures even regarded as taboo (Murdock 1949). Parents nearly universally want their offspring’s future spouse to come from the same ethnic group, the same religion, and the same—or a higher—social class. For example, Hindu women living in the UK indicate that their parents would never accept a son-in-law from outside their caste or culture (Bhopal 1997), and Indian American women tend to find it difficult to forgive their sons for marrying Euro-Americans (Das Gupta 1997). In a study in India, Sprecher and Chandak (1992) found that religion, social class, education, family, and caste were, in descending order, perceived as the most important characteristics for parents in arranging marriages for their children. However, when children had the freedom to choose their own spouse, the traits that were considered most important were an outgoing personality, physical attractiveness, and athleticism.

Studies conducted by Buunk et al. (2008) in various cultures showed that individuals perceived that their parents would object if they chose a mate with traits indicating a poor fit with the in-group, such as a different ethnicity, a different religion, and coming from a lower social class. In contrast, individuals themselves would object to mates with such traits as being physically unattractive and lacking creativity (traits that have been labeled as indicating a lack of “genetic quality”). In general, no sex differences were found, and both young men and young women reported the same discrepancy between their own preferences and those of their parents. These results were first established in culturally diverse samples from the United States, Kurdistan (Iraq), The Netherlands, and international students studying in The Netherlands. Virtually the same results were obtained in Uruguay (Park et al. 2009) and Argentina (Buunk and Castro Solano 2010). In addition, there is evidence that parents agree with their children’s perspective. That is, in a study among parents with children between 15 and 25 years of age, participants perceived characteristics indicating a lack of “genetic quality” as being more unacceptable to their child, whereas characteristics indicating a lack of cooperation with the in-group were more unacceptable to themselves (Dubbs and Buunk 2010a, b). Similarly, research by Apostolou (2008a, b) reveals that people rank the traits “good family background” and “similar religious background” higher when considering the traits they would prefer for their ideal in-law compared with their ideal mate. Marriage statistics are in line with these findings. Although the rate of intermarriage in the Western world has been increasing, it can still be considered rather low. For instance, in the United States only 4% of white Americans marry non-whites (Qian and Lichter 2007), and the reactions to intermarriage often remain negative (Miller et al. 2004).

The Role of Status of the In-group

On the basis of the previous reasoning, we expected that, in general, among parents, higher preferred levels of influence on the mate choice of one’s offspring would be associated with a stronger opposition to interethnic mating. However, in addition to its cohesion and homogeneity, the in-group’s status is also at stake, and in this realm sex differences may occur. Although mothers and kin surely play a role in the mate choice of their offspring in many cultures, historically and cross-culturally it is primarily the fathers who arrange the marriages of their offspring (e.g., Murstein 1974). Indeed, Apostolou (2007) found that male kin, especially fathers, were primarily responsible for the arrangement of the marriages. Since men, unlike women, do not experience a drop in fertility as they grow older, men may still be—at least more so than women—concerned with achieving status and obtaining resources that can increase their mate value. One way fathers can obtain and maintain status is through the marriages of their children. In line with this reasoning, a sample of Dutch women indicated that having a long-term partner with characteristics indicative of low status (a different ethnicity, poverty, a lower social class, and less education) would be perceived as more unacceptable to their father than their mother (Dubbs and Buunk 2010a). In fact, men used—and in some places still use—their daughters as a resource to exchange with other men and to build and expand their alliances. For example, among the Yanomamö of Venezuela, who practice horticulture, marriages are arranged by older kin—usually brothers, uncles, and the father. According to Chagnon (1992), marriage is often a political process in which girls are promised to men in order to create alliances. On the basis of this, we predicted that, in general, a preference for influence on the mate choice of one’s offspring will be more strongly associated with opposition to interethnic mating among fathers than among mothers. This will occur more strongly in high-status groups because it is relatively more important for men from these groups to preserve and enhance the status of the in-group, and they may feel that they have relatively more to lose from their offspring marrying into lower-status groups.

The Mexican Context

The present research was conducted among a rural population in Oaxaca, one of the poorest states in Mexico, and included participants from three major ethnic groups: mestizos, indigenous Mixtecs, and Mexican blacks. Following the Mexican Revolution, the mestizos were promoted as the prototypical Mexicans and a new ideology of mestizaje emerged that defined Mexico as essentially a nation of mixed white and indigenous descent. Around 60% of the Mexican population perceive themselves to be mestizos, around 30% consider themselves to be indigenous people, while 10% consider themselves to have another ethnic identity, including black (around 9% define themselves as white). In Mexico one’s social identity can be quite fluid and is dependent not only on ancestral origins but also to an important extent on political and cultural factors (e.g., Knight 1990). For example, according to Villarreal (2010) upwardly mobile mestizos often try to portray themselves as white, while indigenous people may become mestizos through migration to urban areas and by adopting the dominant culture and language. The difference between mestizos and indigenous people, such as the Mixtecs, is mainly defined in cultural terms, including differences in language and accent, in clothes, and in the type of fiestas. Nevertheless, indigenous cultures have historically been considered inferior (e.g., see Stutzman 1981). It therefore seems safe to state that of the three groups considered in this study, the mestizos have the highest status in Mexican society. Indeed, blacks as well as Mixtecs often feel that they are dominated by mestizos.

The Mixtecs are an indigenous people who number somewhere between 250,000 and 500,000. They are the descendants of the people who constituted one of the major civilizations of Middle America—people who are well-known for their exceptional mastery of jewelry, their codices (phonetic pictures), their history, their art, and their genealogy. The Mixtec region covers most of the current state of Oaxaca. Because of soil erosion, currently the Mixtec cannot sustain themselves via traditional means, and many emigrate to the United States or other parts of Mexico. Money sent home by emigrants is a major source of income for those who remain in Oaxaca. The Mixtecs are considered a very cohesive ethnic group that maintains its identity despite the high level of migration, and Mixtecs often return to their home region (e.g., Joyce 2010).

It is not widely known that Mexico has a black community, but it has been estimated that around 250,000 African slaves were brought to Mexico (Bennett 2009). However, there is a long history of intermarriage between blacks and indigenous people, and most blacks were absorbed into the mestizo population. Consequently, by the end of the colonial era blacks were rarely recognized as a distinct racial or ethnic group (Villarreal 2010). In addition, with the emphasis on being a mestizo as the characteristic Mexican national identity, a separate black social identity was not recognized or encouraged (e.g., Lewis 2000). Many blacks chose to completely assimilate to Mexican society and preferred to be considered mestizos. Recently, however, somewhat more attention has been directed toward the African roots of the Mexican blacks, especially in Veracruz and Oaxaca, which have substantial black populations. The term “Afro-Mexican” is not used in Mexico, and anthropologist Laura Lewis (2000), who has studied Mexican blacks in depth, prefers the latter term. In the present context, we consider the adjective “Mexican” superfluous and simply refer to Afro-Mexicans as blacks (negros), the term generally used in Oaxaca.

Previous research on parental influence on mate choice has not included indigenous groups in the Americas. The three ethnic groups in the present study live closely together in the same area, and given the Mexican ideology favoring mestizaje, one might expect that whether or not their offspring marry out-group members is for all groups a relevant issue. This seems rather obvious considering the many negative stereotypes among the three groups. For example, mestizo and indigenous people often view blacks as violent, impulsive, and lazy, and blacks widely believe themselves to be vulnerable to Indian witchcraft (Lewis 2000). In the present study we examined the extent to which parents in these three ethnic groups stated a preference for influencing the mate choices of their children, in comparison with other populations. In addition, we investigated whether the three ethnic groups differed in the preferred level of parental influence and in opposition to out-group mating, and whether there were gender differences in this respect. The central issue was to what extent parental influence on mate choice was related to a general opposition to mating with out-group members. Based on our previous reasoning, we expected that this would be especially true for fathers and, given their higher status, especially for mestizos. In line with the study among Dutch parents on a similar issue (Dubbs and Buunk 2010b), we chose a sample of parents with children between the ages of 15 to 25 for several reasons. By the age of 15, most children have reached puberty and have begun to show an interest in the opposite sex. In Mexico the mean age at marriage for women is 22.4 and for men, 24.6. Therefore, parents of children between these ages, will generally be, or recently have been, confronted with prospective marital partners for their children; for them, influence on their offspring’s mate choice will be a salient issue.

Methods

Data Collection

A collaborator from Oaxaca who was affiliated with the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS), along with help from her two adult children and two CIESAS scholars, collected the data. The collaborator recruited an equal number of men and women (none of the participants were married to each other), and each participant had to have at least one child between the ages of 15 and 25. The collaborator first obtained permission from the local officials (comisariado) by explaining to them the nature of the research and by showing them the questionnaires. The letter of recommendation from CIESAS convinced the officials that she simply wanted to collect data and would not be promoting any political stance. The officials prescribed the days and times at which she could administer the questionnaire. At these times, people were approached and asked if they fit the criteria, and if they were willing to fill out the questionnaire. Those who live in the mountainous area were especially helpful and respectful, but also quite sensitive; therefore the local officials told the collaborator to visit the families discretely to prevent misunderstandings between families. The participants were paid 65 Mexican pesos (around US$6) for their participation. For the vast majority this was more than their daily income. Although a few people felt the money was not enough, in most places the people were cooperative, and the sample can be considered quite typical for the local population.

Sample

The sample consisted of 203 respondents from three rural ethnic groups. Half of the sample (50%, n = 103) consisted of indigenous Mixtecs, 17% (n = 35) were blacks, and 32% (n = 65) were mestizos. There were about equal numbers of males (n = 100) and females (n = 103), and the sexes were nearly equally distributed over the three ethnic groups. Most women (90%) were housewives, 5% said they had a profession, and 6% indicated they did not have a profession. Of the men, the large majority (74%) were farmers; 10% were fishermen, 16% had a variety of other professions, and 2% indicated that they did not have a profession. Among women, there was no significant difference between ethnic groups in the type of profession reported (\( \chi_{6,103}^2 = 9.58 \) p = 0.14), but among men the difference was significant (\( \chi_{6,100}^2 = {36}.0{6} \) p <0.0001). Among the mestizos (85%) as well as Mixtecs (77%), the vast majority were farmers, and virtually none was a fisherman (0% and 2%, respectively), with similar numbers of other professions (15% and 17%, respectively). In contrast, only half of the blacks were farmers (50%), and nearly as many were fishermen (45%), with few (5%) involved in other professions. The incomes were low: 63% had an income of less than 55 pesos a day (ca. US$4.50), 31% between 55 and 200 pesos a day (between $4.50 and $16), and 6% earned more than 200 pesos a day (ca. $16). The three ethnic groups did not differ in income category (for women, \( \chi_{4,77}^2 = 2.25 \) p = 0.69; for men, \( \chi_{8,97}^2 = 9.97 \) p = 0.28). The women had on average 2.55 (SD = 1.61) daughters and 2.79 (SD = 1.66) sons, whereas the men had on average 2.89 (SD = 1.89) daughters and 2.59 (SD = 1.61) sons. There was no sex difference in the number of children (t-tests; all p values >0.18). The mean age in the sample was 44.79 years for women (SD = 8.09) and 49.85 years for men (SD = 9.91).

Measures

Parental Influence on Mate Choice

To assess parental influence on mate choice (PIM), we used the PIM scale developed by Buunk et al. (2010), which was guided by previous work (e.g., Goode 1959; Hortaçsu and Oral 1994; Pool 1972; Rao and Rao 1976; Riley 1994; Theodorson 1965; Xie and Combs 1996). This scale covers the range of possible forms of parental influence on mate choice (varying from complete autonomy of children to complete control by parents). The scale was developed to be sensitive to variations in the degree of parental influence within and between cultures. For instance, it included an item that represents the most extreme form of parental influence—the practice in which a daughter is treated as property that the father is allowed to give to another man (Goode 1959)—as well as an item that represents the other extreme—the norm that children have the right to select their own partners without any interference from their parents. Participants were asked to give their personal beliefs or opinions. All ten items had the format of a statement with which people could respond on a 5-point scale from “I disagree completely” to “I agree completely.” Seven items consisted of statements expressing parental influence on mate choice, whereas three items consisted of statements expressing individual choice. In the present sample, the reliability was low (α = 0.51). By omitting two items, the reliability could be raised to 0.60. However, to keep our results comparable to those of previous research, we decided to use the same scale. The low alpha reliability is in itself not necessarily a problem because the items were explicitly chosen to represent the entire continuum, and when participants have a clear preference for one level of control, they do not necessarily have a moderate preference for a related level of control. We return to this issue in the “Discussion.” The sum of the scale was divided by the number of items, M = 2.32, SD = 0.62.

Opposition to Interethnic Mating

This scale consisted of six items, based in part on the scale for intergroup mating competition developed by Klavina et al. (2009). Examples of items are “Men and women from different ethnic groups have too different backgrounds to get married,” “People who marry people from another ethnic group are responsible for the deterioration of their community,” “When a man receives attention from many women who want to date him, he should give the priority to the women of his own group,” and “Marrying someone from another ethnic group may cause problems for the children of this marriage.” In the present sample, the reliability was high: α = 0.84.

Results

Level of Parental Influence on Mate Choice Compared with Other Cultures

Overall, the level of parental influence was M = 2.32, SD = 0.62 (possible range from 1 to 5). This was significantly higher than in Argentina (M = 1.49, SD = 0.58, t 441 = 14.69, p < 0.001), and The Netherlands (M = 1.45, SD = 0.49, t 570 = 18.77, p < 0.001). It was also significantly higher than among European Canadians (M = 1.86, SD = 0.49, t 224 = 3.70, p < 0.03), but significantly lower than among East Asian Canadians (M = 2.76, SD = 0.75, t 263 = 4.64, p < 0.001) and among young people from Kurdistan (Iraq) (M = 2.77, SD = 0.67, t 396 = 6.85, p < 0.001) (see Buunk et al. 2010; Buunk and Castro Solano 2010). Thus, the Mexican parents expressed a substantially higher preference for parental influence on the mate choice of their offspring than that found in Western countries, or a Westernized South American country (Argentina), and this preference was even close to that found in the Asian samples, albeit somewhat lower.

Effect of Gender and Ethnic Group Opposition to Interethnic Mating

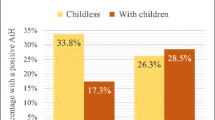

We first examined whether the level of opposition to interethnic mating differed between men and women, and among the three ethnic groups. A univariate GLM analysis with gender and ethnic group as factors showed a significant main effect of gender (F 1, 196 = 5.79, p = 0.02) as well as ethnic group (F 2, 196 = 3.67, p = 0.03). Overall, women (M = 16.28, SD = 7.91) showed a higher level of opposition to interethnic mating than men did (M = 14.21, SD = 6.50), and mestizos (M = 17.57, SD = 8.92) showed a higher level than both Mixtecs (M = 14.43, SD = 6.11) and blacks (M = 13.43, SD = 6.26) did. These effects were qualified, however, by a highly significant interaction between gender and ethnic group (F 2, 196 = 7.41, p = 0.00) that was primarily driven by female mestizos (Fig. 1). Separate analyses within the three ethnic groups showed that the sex difference was significant only among mestizos (t 63 = 3.21, p = 0.00), with women (M = 20.37, SD = 9.24) showing a higher level of opposition to interethnic mating than men (M = 13.63, SD = 6.85). There was no significant sex difference among Mixtecs, t 100 = 1.42, p = 0.16 (for women, M = 13.56, SD = 5.75; for men, M = 15.27, SD = 6.38), nor among blacks, t 33 = 1.30, p = 0.20 (for women, M = 15.00, SD = 6.35; for men, M = 12.25, SD = 6.09). Further corroborating these findings, among men there was no effect of ethnic group on opposition to interethnic mating, F 2, 98 = 1.73, p = 0.18, but among women the effect of ethnic group was highly significant, F 2, 102 = 9.63, p = 0.00, and post hoc tests revealed that mestizo women were significantly more opposed to interethnic mating than Mixtec women (p = 0.00), and nearly significantly more than black women (p = 0.06), but that these last two groups did not differ from each other (p = 0.80).

Effect of Gender, Ethnic Group, and Opposition to Interethnic Mating on Parental Influence on Mate Choice

To examine the central issue in this research—how a preference for parental influence onmate choice was related to opposition to interethnic mating for men and women in the three ethnic groups—we conducted a univariate GLM analysis with gender and ethnic group as factors, and avoidance of intergroup marriage as covariate. All main effects and interactions were included in the model. In the full model there was no effect of ethnic group on the preferred level of parental influence, F 2, 190 = 0.19, p = 0.83. Gender had a significant effect (F 1, 190 = 6.81, p = 0.01), but this effect was qualified by a highly significant interaction between gender and ethnic group (F 2, 190 = 6.76, p = 0.00; Fig. 2). Separate analyses within the three ethnic groups showed that only among the Mixtecs was there a significant sex difference (t 101 = 2.11, p = 0.04), with men (M = 2.45, SD = 0.54) being more in favor of parental influence on the mate choice of children than women (M = 2.21, SD = 0.64). The sex difference was not significant among blacks and mestizos (t values < 1.16; p values > 0.24).

Opposition to interethnic mating had a highly significant effect on parental influence on mate choice (F 1, 189 = 30.97, p = 0.00), indicating that, overall, those in favor of avoiding intergroup mating were more in favor of controlling the mate choice of one’s offspring. However, while there was no significant interaction between opposition to interethnic mating and ethnic group (F 2, 189 = 0.09, p = 0.92), there was a significant interaction between gender and opposition to intergroup marriage (F 2, 189 = 8.03, p = 0.00) that was qualified by a significant three-way interaction between gender, ethnic group, and opposition to interethnic mating (F 2, 189 = 5.72, p = 0.00). Follow-up regression analyses within men and women separately showed that, as predicted, the effect of opposition to interethnic mating on parental influence on mate choice was highly significant among men (β = 0.54, t 97 = 6.32, p = 0.00) and only marginally significant among women (β = 0.17, t 102 = 1.74, p = 0.09). But, as suggested by the three-way interaction, this gender difference was different for the three ethnic groups (Fig. 3). Among the Mixtecs, the effect of opposition to interethnic mating was highly significant for men (β = 0.40, t 50 = 3.04, p = 0.00) as well as women (β = 0.37, t 48 = 2.80, p = 0.00). However, among blacks the effect was significant among men (β = 0.49, t 18 = 2.40, p = 0.03) but not among women (β = 0.13, t 14 = 0.46, p = 0.66), and among mestizos the difference between men and women was the most pronounced (for men, β = 0.73, t 25 = 5.41, p = 0.00, and for women, β = 0.04, t 36 = 0.22, p = 0.83). To summarize, among blacks, and especially among mestizos, for men, but not for women, a preference for influencing the mate choice of one’s offspring was associated with opposition to mating with members of other ethnic groups. Thus, the predicted gender difference in this respect was found among these two ethnic groups, but not among the Mixtecs.

Discussion

The present research examined the preferred levels of parental influence on one’s offspring’s mate choice in three ethnic groups in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. Overall, the preferred level was considerably higher than that in Argentina and Uruguay—both Westernized South American countries—and lower than that in Asian populations. Nevertheless, it was relatively closer to the level in the latter populations. The three ethnic groups did not differ in this respect. This finding suggests that black, Mixtec, as well as mestizo parents all believe to a considerable degree that individuals should follow the preferences of their parents when choosing a mate. These findings can be interpreted in various ways. First, since most people in these groups live close to their extended kin, parental influence is likely to be stronger than in more individualistic cultures. In fact, there may still be a considerable indigenous cultural influence on marital patterns, taking the plausible assumption that arranged marriages were the predominant pattern among the indigenous populations of Mesoamerica. Second, the findings may in part reflect a Spanish influence—in Spain parents historically maintained substantial control over the mating behavior of their offspring, and at least in the beginning of colonization, this was also the case in the Spanish colonies in the Americas (e.g., Gutierrez 1985). Finally, the relatively high level of parental control over mate choice may result from the fact that people in Oaxaca live close to many other ethnic groups and may feel that they need to protect their own group from being weakened by intergroup marriages.

Only among Mixtecs did men favor more parental influence on the mate choice of their offspring than women did. This finding may be interpreted from the perspective that, unlike the other ethnic groups, Mixtecs are an indigenous American population in which it may have been primarily the males who used their control over the mate choice of their offspring to build alliances and to obtain mates. As noted above, among indigenous people, marriages are a common way to build alliances between families. This interpretation receives support from the fact that among Mixtec men, opposition to interethnic mating was less strongly related to a preference for influence on one’s offspring’s mate choice than among men of the other two ethnic groups. Perhaps considerations other than preventing out-group mating were more important for Mixtec men than for mestizo and black men. Such considerations may include the option of marrying out one’s daughter to men of other groups.

The main prediction was supported: overall, among men there was a much stronger association between opposition to interethnic mating and preference for parental influence on one’s offspring’s mate choice than among women, and this sex difference was especially pronounced among mestizos. This supports our assumption that, since mestizos have the highest status of the ethnic groups investigated here, and preserving one’s status is especially important for males, fathers particularly in this group will be inclined to control the mate choice of their offspring to the extent that it will contribute to family and group cohesion by excluding matings with out-group members. It is not that mestizo fathers want to control the mate choice of their offspring more than fathers in the lower-status groups do, but that among mestizo fathers the desire to control the mate choice of one’s offspring seems more closely related to the intention of preventing children from choosing members from other ethnic groups as mates. Overall, the fact that the motivation to prevent marriage to out-group members was quite strongly related to the preference for controlling the mate choice of one’s offspring is in line with a plethora of studies showing that in a wide variety of cultures, a major concern of parents is that the mate comes from the same ethnic and religious group (e.g., Buunk et al. 2008). This also illustrates that the desire to maintain the homogeneity and cohesion of the in-group is as important as gaining status: even parents from low-status groups usually prefer their offspring to marry someone from the same ethnic and religious group. Significantly, the Mixtecs were the only ethnic group in this study in which opposition among men and women to interethnic mating was to a similar degree associated with a preference for parental influence on the mate choice of one’s offspring. This might reflect the fact that this indigenous group is particularly keen on preserving the homogeneity of their group by controlling the mate choice of their children.

Overall, women had a stronger opposition to out-group mating than men had, and mestizo women showed a stronger opposition than women from the other two ethnic groups. This may be explained by the fact that mestizos have the highest status, and therefore women from this group have little to gain from mating with out-group members of lower status since women typically pay much more attention to the status of a potential mate than men do (e.g., Buss 1994). On the other hand, men from this group may have much more to gain from intergroup mating: since they have the highest status of all ethnic groups, they may benefit most from having access to women from the other groups. This sex difference is in line with evidence that men tend to be more open to marrying and dating members of other ethnic groups than women are (e.g., Feliciano et al. 2009). For example, a study by Tucker and Mitchell-Kernan (1995) in California found that among blacks, whites, and Latinos, men engaged in interethnic dating considerably more often than women did. The sex difference in the attitude toward mating with out-group members may reflect that throughout human history men have forcibly taken women from other groups (e.g., Wrangham and Peterson 1996; Chagnon 1988). This implies that men will often see men from other groups as competitors. In line with this, whereas men are more open to out-group mating, they tend to have generally more negative attitudes toward and prejudices against members of other groups than women do (e.g., Pratto et al. 2006).

This study has a number of potential limitations. First, aside from opposition to out-group mating, we did not explore other factors that might affect preferred levels of parental control over mate choice, and participants were not directly asked why they preferred having parental control over their offspring’s mate choice. In addition, we did not directly assess the desire to improve one’s status, which may influence, especially among males, the inclination to control the mate choice of one’s offspring. Second, the reliability of the parental influence measure was low in this sample, which may in part be due to the fact that the items were developed to cover a wide range of behaviors and attitudes related to parental control over children’s mate choice. Because the items of the PIM scale can be ordered on a continuum from strong disapproval to strong approval of parental influence, this scale does not necessarily have to meet the criteria of a Likert scale. Nevertheless, we did find quite consistent and in part quite strong effects, which suggests that the scale is a useful measure. Third, we had uneven numbers of participants in the three groups: blacks were underrepresented, which may have reduced the ability of our analysis to identify effects. However, most effects were sufficiently robust to be identified even in the relatively small black sample. Finally, we cannot say with absolute certainty that the samples were representative for the populations studied, since a number of people refused to participate, and it was not possible to draw a random sample from each group. Nevertheless, the data collection was done very conscientiously, and there is no reason to assume that there is a substantial bias in the sample.

To conclude, we collected data from parents in a unique setting—a rural region with different ethnic groups that live in close contact with each other. We included in our research in addition to the mestizos—who constitute the majority of Mexican inhabitants—an indigenous people (Mixtecs) as well as rarely studied black Mexicans. We showed that in the populations that we studied the preferred level of parental influence on mate choice was relatively high, and that opposition to mating with members of other ethnic groups was an important factor underlying a positive attitude toward controlling the mate choice of one’s offspring. We found often subtle, but theoretically meaningful differences between men and women and among the three ethnic groups. By examining how cultural factors and gender affect parental influence on mate choice, our research indicates that mate choice may be to an important extent affected by the parents. In general, our research further exemplifies that for a more complete understanding of human mating, future research must attend more carefully to the role of parents in the mate choice of their children.

References

Apostolou, M. (2007). Sexual selection under parental choice: the role of parents in the evolution of human mating. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 403–409.

Apostolou, M. (2008a). Parent-offspring conflict over mating: the case of beauty. Evolutionary Psychology, 6, 303–315.

Apostolou, M. (2008b). Parent-offspring conflict over mating: the case of family background. Evolutionary Psychology, 6, 456–468.

Applbaum, K. D. (1995). Marriage with the proper stranger: arranged marriage in the metropolitan Japan. Ethnology, 34, 37–51.

Bennett, H. L. (2009). Colonial blackness: A history of Afro-Mexico. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bhopal, K. (1997). South Asian women within households: dowries, degradation and despair. Women’s Studies International Forum, 20, 483–492.

Burbank, V. K. (1995). Passion as politics: Romantic love in an Australian Aboriginal community. In W. Jankowiak (Ed.), Romantic passion: A universal experience? (pp. 196–218). New York: Columbia University Press.

Buss, D. M. (1994). The strategies of human mating. American Scientist, 82, 238–249.

Buunk, A. P., & Castro Solano, A. (2010). Conflicting preferences of parents and offspring over criteria for a mate: a study in Argentina. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 391–399.

Buunk, A. P., Park, J. H., & Dubbs, S. L. (2008). Parent-offspring conflict in mate preferences. Review of General Psychology, 12, 47–62.

Buunk, A. P., Park, J. H., & Duncan, L. A. (2010). Cultural variation in parental influence on mate choice. Cross-Cultural Research, 44(1), 23–40.

Chagnon, N. A. (1988). Life histories, blood revenge, and warfare in a tribal population. Science, 239, 985–992.

Chagnon, N. A. (1992). Yanomamö: The last days of Eden. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Das Gupta, M. (1997). “What is Indian about you?” A gendered, transnational approach to ethnicity. Gender and Society, 11, 572–596.

Dubbs, S. L., & Buunk, A. P. (2010a). Sex differences in parental preferences over a child’s mate choice: a daughter’s perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 1051–1059.

Dubbs, S. L., & Buunk, A. P. (2010b). Parents just don’t understand: parent-offspring conflict over mate choice. Evolutionary Psychology, 8, 586–598.

Dugsin, R. (2001). Conflict and healing in family experience of second-generation emigrants from India living in North America. Family Process, 40, 233–241.

Faulkner, J., & Schaller, M. (2007). Nepotistic nosiness: inclusive fitness and vigilance of kin members’ romantic relationships. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 430–438.

Feliciano, C., Robnett, B., & Komaie, G. (2009). Gendered racial exclusion among white Internet daters. Social Science Research, 38, 39–54.

Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (1966). Industrialization and the American family: a look backward. American Sociological Review, 31, 326–337.

Gautam, S. (2002). Coming next: monsoon divorce. New Statesmen, 131, 32–33.

Goode, J. W. (1959). The theoretical importance of love. American Sociological Review, 24, 38–47.

Gutierrez, R. A. (1985). Honor ideology, marriage negotiation, and class-gender domination in New Mexico, 1690–1846. Latin American Perspectives, 12, 81–104.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Hortaçsu, N., & Oral, A. (1994). Comparison of couple- and family-initiated marriages in Turkey. Journal of Social Psychology, 134, 229–239.

Hynie, M., Lalonde, R. N., & Lee, N. (2006). Parent-child value transmission among Chinese immigrants to North America: the case of traditional mate preferences. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12, 230–244.

Joyce, A. A. (2010). Mixtecs, Zapotecs and Chatinos: Ancient peoples of southern Mexico. Malden: Wiley Blackwell.

Klavina, L., Buunk, A. P., & Park, J. H. (2009). Intergroup jealousy: Effects of perceived group characteristics and intrasexual competition between groups. In H. Hogh-Olesen, J. Tonnesvang, & P. Bertelsen (Eds.), Human characteristics: Evolutionary perspectives on human mind and kind (pp. 382–397). Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars.

Knight, A. (1990). Racism, revolution and indigenismo: Mexico, 1910–1940. In R. Graham (Ed.), The idea of race in Latin America (pp. 71–113). Austin: University of Texas Press.

Lalonde, R. N., Hynie, M., Pannu, M., & Tatla, S. (2004). The role of culture in interpersonal relationships: do second generation South Asian Canadians want a traditional partner? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35, 503–524.

Levine, R., Sato, S., Hashimoto, T., & Verma, J. (1995). Love and marriage in eleven cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 26, 554–571.

Lewis, L. A. (2000). Blacks, black Indians, Afromexicans: the dynamics of race, nation and identity in a Mexican moreno community (Guerrero). American Ethnologist, 27, 898–926.

Madathil, J., & Benshoff, J. M. (2008). Importance of martial characteristics and martial satisfaction: a comparison of Asian Indians in arranged marriages and Americans in marriages of choice. The Family Journal, 16, 222–230.

Menon, R. (1989). Arranged marriages among South Asian immigrants. Sociology and Social Research, 73, 180–182.

Miller, S. C., Olson, M. A., & Fazio, R. H. (2004). Perceived reactions to interracial romantic relationships: when race is used as a cue to status. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 7, 354–369.

Mitchell, R. E. (1970). Changes in fertility rates and family size in response to changes in age at marriage, the trend away from arranged marriages, and increasing urbanization. Population Studies, 25, 481–489.

Murdock, G. P. (1949). Social structure. Oxford: Macmillan.

Murstein, B. I. (1974). Love, sex, and marriage through the ages. New York: Springer.

Park, J. H., Dubbs, S. L., & Buunk, A. P. (2009). Parents, offspring and mate-choice conflicts. In H. Høgh-Olesen, J. Tønnesvang, & P. Bertelsen (Eds.), Human characteristics: Evolutionary perspectives on human mind and kind (pp. 352–365). Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Perilloux, C., Fleischman, D. S., & Buss, D. M. (2008). The daughter guarding hypothesis: parental influence on, and emotional reactions to, offspring’s mating behavior. Evolutionary Psychology, 6, 217–233.

Pimentel, E. E. (2000). Just how do I love thee?: Martial relations in urban China. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 32–47.

Pool, J. E. (1972). A cross-comparative study of aspects of conjugal behavior among women of three West African countries. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 6, 233–259.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. (2006). Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: taking stock and looking forward. European Review of Social Psychology, 17, 271–320.

Qian, Z., & Lichter, D. T. (2007). Social boundaries and marital assimilation: interpreting trends in racial and ethnic intermarriage. American Sociological Review, 72, 68–94.

Rao, V. V., & Rao, V. N. (1976). Arranged marriages: an assessment of the attitudes of the college students in India. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 7, 433–453.

Reiss, I. L. (1980). Family systems in America. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Riley, N. E. (1994). Interwoven lives: parents, marriage, and guanxi in China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56, 791–803.

Shostak, M. (1983). Nisa: The life and words of a !Kung woman. New York: Vintage Books.

Sprecher, S., & Chandak, R. (1992). Attitudes about arranged marriages and dating among men and women from India. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology, 20, 59–70.

Stutzman, R. (1981). El Mestizaje: An all-inclusive ideology of exclusion. In N. Whitten (Ed.), Cultural transformation and ethnicity in modern Ecuador (pp. 45–94). Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Talbani, A., & Hasanali, P. (2000). Adolescent females between tradition and modernity: gender role socialization in South Asian immigrant culture. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 615–627.

Theodorson, G. A. (1965). Romanticism and motivation to marry in the United States, Singapore, Burma and India. Social Forces, 44, 17–27.

Tucker, M. B., & Mitchell-Kernan, C. (1995). Social structural and psychological correlates of interethnic dating. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12, 341–361.

United Nations Population Fund (2005). UNFPA child marriage factsheet. Accessed online 19 Oct 2010 at http://www.unfpa.org/swp/2005/presskit/factsheets/facts_child_marriage.htm.

Villarreal, A. (2010). Stratification by skin color in contemporary Mexico. American Sociological Review, 75, 652–679.

Wight, D., Williamson, L., & Henderson, M. (2006). Parental influences on young people’s sexual behavior: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 473–494.

Wrangham, R., & Peterson, D. (1996). Demonic males: Apes and the origins of human violence. London: Bloomsbury.

Xie, X., & Combs, R. (1996). Family and work roles of rural women in a Chinese brigade. International Journal of Sociology of the Family, 26, 67–76.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work was supported by a grant from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences to Abraham Buunk, and a NWO Veni grant to Thomas Pollet (451.10.032). We thank Alejandra Cruz from CIESAS and her collaborators for their conscientious fieldwork.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buunk, A.P., Pollet, T.V. & Dubbs, S. Parental Control over Mate Choice to Prevent Marriages with Out-group Members. Hum Nat 23, 360–374 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-012-9149-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-012-9149-5