Abstract

Snub publishing is a new term that was coined in 2013 to describe a range of publishing cases in which the failure of quality control manifested itself through references in such a way that it would cause unintended damage to snubbed scientists whose names or identity were incorrectly represented in the literature. In this paper, real case studies are presented, mostly related to the author as a “victim” of incompetent editorial oversight, inexperienced or biased authors, or as a “victim” of direct professional conflicts of interest. In essence, this paper serves as a prototype showing in concrete terms how a scientist can or may be professionally snubbed (intentionally or unintentionally). Using the Anthurium literature, this paper aims to raise awareness about snub publishing and seeks to encourage other scientists to also quantify how they too may have been professionally snubbed in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Who Snubs and Who Gets Snubbed?

Snub publishing (SP), a novel term coined in early 2013, is defined as “the intentional or unintentional omission of important references in a scientific paper, the erroneous or deliberate manipulation of a name such that it becomes distorted in the literature, or the removal of a name from a manuscript’s author’s list” [1].

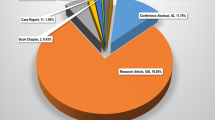

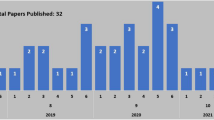

This paper deals with 26 case studies of the former two situations, all directly related to Anthurium, an important ornamental plant. Anthurium was selected due to the personal involvement of the author with this plant and due to the relatively limited literature that exists on this plant, approximately 150 papers in total until 2013 in any available data-base. The first place for scientists to initiate a search of the literature when starting to write a paper (and in fact earlier when researching the literature regarding their experimental design) would be public data-bases such as Google Scholar, Yahoo, or in publisher’s data-bases such as Elsevier’s Sciencedirect, Springer’s SpringerLink, Taylor and Francis/Informa, or Wiley-Blackwell’s Wiley Online, NIH’s PubMed, among others. If one were to enter the terms “anthurium” and “Teixeira da Silva”, the author’s family name, into these data-bases, one would come across several papers published by the author and his collaborators [i.e., 2–7]. The first two papers [2, 3] are available as open access PDF files and are readily downloadable from the first page of a Yahoo or Google search. The remaining Winarto papers [4–7] are prominently visible on Elsevier and Springer data-bases. In other words, these papers are highly visible and easily accessible, much more than in fact many other anthurium papers. In these data-bases, the family name, Teixeira da Silva, is clear. The anthurium in vitro and micropropagation literature between 2006 and 2013 encompasses (excluding the papers listed above) approximately 34 papers for Anthurium andreanum Hort. and 5 papers for other Anthurium spp. Usually, with such a limited literature, scientists would search the literature carefully to obtain as much information as possible to develop the Introduction and Discussion of a manuscript, at least in theory. Oddly, the name Teixeira da Silva, when crossed with the terms “anthurium”, and “in vitro” or “micropropagation” on the above indicated data-bases does not link to the 26 papers published between 2006 and 2013 while only eight did. This oddity spurred an informal investigation that led to the findings of this paper. Upon closer examination of the 26 papers, listed next as Cases 1–26, each with their own screenshot(s) represented by Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and 26, respectively, it is abundantly evident that the authors of these 26 papers have misrepresented the name of the author, reducing it to Silva JA, Silva JAT, or other even more indescribable forms, or errors. In essence, each error represents a professional snub. Next listed are the authors, the country of origin and the figure number.

Only studies from 2006 were considered since the objective was to assess which papers after the author’s earliest study [2] had been snubbing his identity. In every single case, two clear aspects are obvious. Firstly, there has been author negligence in not ensuring that the name of the author of the study that they were referencing was correct. Even so, an astute scientist would easily be able to identify the family name from the published paper and represent it faithfully in their text and reference list. There may be some cultural bias since in most of these cases, the most frequent being from Indian scientists (31 % of all cases), a cultural ignorance of global scientists’ names may exist. The fact that 26 papers by scientists from 15 countries misrepresented my professional name in the literature is of great concern and shows just how wide-spread snub publishing may be taking place. The second glaring aspect that is revealed by this error in the incorrect or fraudulent representation of my professional name is the serious level of editorial oversight and possibly inadequate or biased peer review. Peer reviewers and editors have the responsibility to ensure the scientific integrity of a manuscript, to ensure that the information contained therein is accurate and correct, including the name of authors and peers in that field of study. This is also a basic requirement of authors [34]. When submitting to a journal that would be reviewing a paper on anthurium, one would expect that an anthurium specialist would be revising the manuscript. An anthurium specialist or even ornamental scientist who is familiar with this literature would undoubtedly have identified that my name had been incorrectly represented and would have then requested the authors to correct the record. The fact that 26 papers failed to detect such a basic error provides evidence that no, fake, unprofessional or incomplete peer review took place. Such a pseudo-peer review would essentially render the scientific quality and integrity of the paper invalid since it would run counter to what all these journals are advertising, i.e., that they are peer reviewed international journals. A non-peer reviewed or poorly peer reviewed paper should, very plainly stated, never have been published. According to [1], all of these 26 papers would receive a snub score of 2–3 on a scale of 1–8, according to Table 1 in that paper. Moreover, the existence of snub publishing is one characteristic of predatory open access publishers [35].

What are the consequences of snub publishing? The very first and most obvious one is that the snubbed scientist, in this case the author as an example, will have lost 26 opportunities to be referenced accurately in the literature. Potentially, this could translate into 26 opportunities for indexing in data-bases and thus the potential loss of dozens of valid literature attributions over the past 8 years. For a scientist, one of the most important aspects is for their work to be referenced. But if their names are not being accurately or correctly referenced, then what is the purpose of even being referenced, or even publishing for that matter when the peer pool appears to act irresponsibly? The second unintentional but direct consequence is that any researcher from now on (2014-future) who reads any of these snub papers will potentially carry forward the fraud (claimed so because information is falsely represented) into the future literature and its reference lists, especially if the authors of as-yet-to-be published papers do not bother to access the original source. The risk of professional damage thus becomes not linear, but exponential. In this case, we are referring to a plant with limited research (average of between 5 and 10 papers yearly in the global literature), but the dimension of the damage caused were the plant to be tomato, maize, wheat or another major crop, could be devastating to a career and a curriculum vitae.

Why would such false and fraudulent representation of an author’s name not be considered libel? Why would the authors not be held accountable for correcting the literature? Why would the editors, journals and publishers not be held accountable and be made to publish errata to set the academic record straight? In cases where an author feels that their name has been snubbed, and that their name is not correctly represented in the literature, they should have the right to request the publisher to correct the scientific record and to publish an erratum.

SP is one form of predatory publishing, but in which the act of predation might be used by the author, using a journal or publisher in an unsuspecting manner, to derive benefit in a dishonest or fraudulent way, or to inflict damage to the professional status or image of another scientist, possibly a competitor. SP can be subtle, or can be blatant. This paper shows one case of how SP takes place in both veiled and blunt forms.

Conclusions

The acts that define SP have most likely always been present throughout the history of publishing. Yet, the fact that a concrete term to this phenomenon has now been assigned, and somewhat qualified in this paper, brings to light a new form of fraud in science publishing that deserves greater scrutiny. Other scientists are urged to examine the text and reference lists of their own papers within fields of science that they are specialists of to begin to quantify the level of SP that is taking place in the open access and print literature. References suddenly become a form by which fraud is permitted, legalized and perpetuated. The legitimization of false and inaccurate information through SP by predatory publishers, by ignorant or lazy authors, or by careless editors, peers and journals must not be allowed to continue unpunished, otherwise there will be no sense of justice and correction of the scientific record for posterity [36].

Regrettably, when data and figure duplication (partial or total)—for example, [9] and [37] or [28] and [38]—are allowed to remain published without any action by the authors, publishers or peer community, in this case the anthurium, horticultural and plant science communities, or without any repercussions, these very same communities should not be surprised when the system of ethical publishing implodes once total failure in quality control has been lost. In such cases, quality control must be implemented by scientists and the peer pool in an independent analysis, using one key tool, post-publication peer review [39].

Napoleon Bonaparte once stated “Never ascribe to malice that which is adequately explained by incompetence”, which may be pertinent to the topic at hand. However, whether errors in the literature are introduced via malice or via incompetence does not remove the fact that they remain errors in the literature and that they should be corrected.

References

Teixeira da Silva JA. Snub publishing: theory. Asian Australas J Plant Sci Biotechnol. 2013;7(Special Issue 1):35–7.

Teixeira da Silva JA, Murasei F, Tanaka M. Growth vessel and substrate affect Anthurium micropropagation. Plant Tissue Cult. 2005;15(1):1–6.

Viégas J, da Rocha MTR, Ferreira-Moura I, Corrêa MGS, da Silva JB, dos Santos NC, Teixeira da Silva JA. Anthurium andraeanum (Linden ex André) culture: in vitro and ex vitro. Floriculture and ornamental. Biotechnology. 2007;1(1):61–5.

Winarto B, Mattjik NA, Teixeira da Silva JA, Purwito A, Marwoto B. Ploidy screening of anthurium (Anthurium andreanum Linden ex André) regenerants derived from anther culture. Sci Hortic. 2010;127:86–90.

Winarto B, Rachmawati F, Pramanik D, Teixeira da Silva JA. Morphological and cytological diversity of regenerants derived from anthurium anther culture. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2011;105(3):363–74.

Winarto B, Rachmawati F, Teixeira da Silva JA. New basal media for half-anther culture of Anthurium andreanum Linden ex André cv. Tropical. Plant Growth Regul. 2011;65(3):513–29.

Winarto B, Teixeira da Silva JA. Influence of isolation technique of half-anthers and of initiation culture medium on callus induction and regeneration in Anthurium andreanum. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2012;110(3):401–11.

Atak Ç, Çelik Ö. Micropropagation of Anthurium spp. In: Plant science. Intech, Croatia; 2012. p. 241–54.

Raad MK, Zanjani SB, Shoor M, Hamidoghli Y, Sayyad AR, Kharabian-Masouleh A, Kaviani B. Callus induction and organogenesis capacity from lamina and petiole explants of Anthurium andreanum Linden (Casino and Antadra). Aust J Crop Sci. 2012;6(5):928–37.

Gantait S, Sinniah UR, Mandal N, Das PK. Direct induction of protocorm-like bodies from shoot tips, plantlet formation, and clonal fidelity analysis in Anthurium andreanum cv. CanCan. Plant Growth Regul. 2012;67:257–70.

Farsi M, Taghavizadeh Yazdi ME, Qasemiomran V. Micropropagation of Anthurium andreanum cv. Terra. Afr J Biotechnol. 2012;11(68):13162–6.

Pinto de Carvalho ACP, Pinheiro MVM, Martins FB, Ferreira da Cruz FC, Otoni WC. Produção de mudas micropropagadas de antúrio (Anthurium andraeanum) cv. Eidibel por embriogênese somática. Embrapa Circ Técnica (Fortaleza). 2012;41:1–14.

Ancy D, Bopaiah AK, Reddy JM. In vitro seed culture studies in Anthurium bicolor (Agnihothri). Int J Integr Sci Innov Technol. 2012;1(4):16–20.

Bliss BJ, Suzuki JY. Genome size in Anthurium evaluated in the context of karyotypes and phenotypes. AoB Plants pls006; 2012.

Reddy JM, Bopaiah AK. Studies on the intiation [sic] of callusing and regeneration of plantlets in three different basal media with varied plant growth regulators for the micropropagation of Anthurium scherzeriaum [sic] using leaf and spathe as explants. Afr J Biotechnol. 2012;11(23):6259–68.

Sedaghati B, Babaeiyan N-A, Bagheri N-A, Salehiyan H, Khademian R. Effect of type and concentration of growth regulators on plant regeneration of Anthurium andraeanum. Int J Agric Res Rev. 2012;2(S):998–1004.

Gantait S, Sinniah UR. Morphology, flow cytometry and molecular assessment of ex-vitro grown micropropagated anthurium in comparison with seed germinated plants. Afr J Biotechnol. 2012;10(64):13991–1399867.

Kumari S, Desai JR, Shah RR. Callus mediated plant regeneration of two cut flower cultivars of Anthurium andraeanum Hort. J Appl Hortic. 2011;13(1):37–41.

Gantait S, Mandal N. Tissue culture of Anthurium andreanum: a significant review and future prospective. Int J Botany. 2010;6(3):207–19.

Harb EM, Talaat NB, Weheeda BM, El-Shamy M, Omira GA. Micropropagation of Anthurium andreanum from shoot tip explants. J Appl Sci Res. 2010;6(8):927–31.

Islam SA, Dewan MMR, Mukul MHR, Hossen MA, Khatun F. In vitro regeneration of Anthurium andreanum cv. Nitta. Bangladesh J Agric Res. 2010;35(2):217–26.

Atak Ç, Çelik Ö. Micropropagation of Anthurium andraeanum from leaf explants. Pak J Bot. 2009;41(3):1155–61.

Jahan MT, Islam MR, Khan R, Mamun ANK, Ahmed G, Hakim L. In vitro clonal propagation of anthurium (Anthurium andraeanum L.) using callus culture. Plant Tissue Cult Biotechnol. 2009;19(1):61–9.

Kurnianingsih R, Marfuah, Matondang I. Pengaruh pemberian bap (6-benzyl amino purine) pada media multiplikasi tunas Anthurium hookerii Kunth. Enum. secara in vitro. Vis Vitalis. 2009;2(2):23–30 (in Indonesian with English abstract).

Liendo M, Mogollón N. Multiplicación clonal in vitro del anturio (Anthurium andraeanum Lindl. cv. Nicoya). Bioagro. 2009;21(3):179–82 (in Spanish with English abstract).

Yu YX, Liu L, Liu JX, Wang J. Plant regeneration by callus-mediated protocorm-like body induction of Anthurium andraeanum Hort. Agric Sci China. 2009;8(5):572–7.

Bejoy M, Sumitha VR, Anish NP. Foliar regeneration in Anthurium andreanum Hort. cv. Agnihothri. Biotechnology (Pakistan). 2008;7(1):134–8.

Beyramizade E, Azadi P, Mii M. Optimization of factors affecting organogenesis and somatic embryogenesis of Anthurium andreanum Lind. Tera. Propag Ornam Plants. 2008;8:198–203.

Gantait S, Mandal N, Bhattacharyya S, Das PK. In vitro mass multiplication with pure genetic identity in Anthurium andreanum Lind. Plant Tissue Cult Biotechnol. 2008;18(2):113–22.

del Rivero-Bautista N, Agramonte-Peñalver D, Barbón-Rodríguez R, Camacho-Chiu W, Collado-López R, Jiménez-Terry F, Pérez-Peralta M, Gutiérrez-Martínez O. Somatic embryogenesis in (Anthurium andraeanum Lind.) variety ‘Lambada’. Ra Ximhai. 2008;4(1):135–49 (in Spanish with English abstract).

Lima FC, Ulisses C, Camara TR, Cavalcante UMT, Albuquerque CC, Willadino L. Anthurium andraeanum Lindl. cv. Eidibel in vitro rooting and acclimation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Agrarias (Recife). 2006;1:13–6.

Nhut DT, Duy N, Vy NNH, Khue CD, Khiem DV, Vinh DN. Impact of Anthurium spp. genotype on callus induction derived from leaf explants, shoot and root regeneration capacity from callus. J Appl Hortic. 2006;8(2):135–7.

Te-chato S, Susanon T, Sontikun Y. Cultivar, explant type and culture medium influencing embryogenesis and organogenesis in Anthurium spp. Songklanakarin J Sci Technol. 2006;28(4):717–22.

Teixeira da Silva JA. Responsibilities and rights of authors, peer reviewers, editors and publishers: a status quo inquiry and assessment. Asian Australas J Plant Sci Biotechnol. 2013;7(Special Issue 1):6–15.

Teixeira da Silva JA. Predatory publishing: a quantitative assessment, the predatory score. Asian Australas J Plant Sci Biotechnol. 2013;7(Special Issue 1):21–34.

Teixeira da Silva JA. How to better achieve integrity in science publishing. Eur Sci Ed. 2013;39(4):97-8.

Raad MK, Zanjani SB, Sayyad AR, Maghsudi M, Kaviani B. Effect of cultivar, type and age of explants, light conditions and plant growth regulators on callus formation of anthurium. Am–Eurasian J Agric Environ Sci. 2012;12(6):706–12.

Beyramizade E, Azadi P. Effect of growth regulators on shoot formation of Anthurium andreanum Lind. Tera. Pajouhesh & Sazandegi. 2008;76:179–84 (in Farsi with English abstract).

Teixeira da Silva JA. The need for post-publication peer review in plant science publishing. Frontiers Plant Sci. 2013;4:485.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Teixeira da Silva, J.A. Snub Publishing: Evidence from the Anthurium Literature. Pub Res Q 30, 166–178 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-014-9355-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-014-9355-6