Abstract

Solitary fibrous tumors (SFTs) are rare tumors in the head and neck, and even more so in the parotid gland. The mass-like clinical presentation and histologic features result in frequent misclassification, resulting in inappropriate clinical management. There are only a few reported cases in the English literature. Twenty-one patients with parotid gland solitary fibrous tumor were compiled from the English literature (Medline 1960–2011) and integrated with this case report. The patients included 11 males and 11 females, aged 11–79 years (mean, 51.2 years), who presented with a parotid gland painless mass gradually increasing in size or with compression symptoms, with a mean duration of symptoms of 24.7 months. The mean tumor size was 4.5 cm. Grossly, all tumors were described as well-circumscribed to encapsulated, firm, homogenous white to tan masses. Seven patients had a preoperative fine needle aspiration performed, with the majority interpreted to represent pleomorphic adenoma or cementifying fibroma. Histologically, the tumors were well circumscribed, although many tumors showed focally entrapped normal salivary gland acini and ducts at the edge. The tumors were cellular, arranged in haphazard short interlacing fascicles of spindled to epithelioid cells. The spindled cells showed tapering cytoplasm with monotonous, round to oval nuclei with coarse nuclear chromatin distribution. Keloid-like to wiry collagen was present between the neoplastic cells. Mitoses were identified in most cases, while necrosis was absent. Isolated, patulous vessels were present, but a well developed “hemangiopericytoma-like” vascular pattern was not seen. Three tumors were classified as malignant, showing marked nuclear pleomorphism and increased mitoses. When immunohistochemistry was performed, all tumors showed strong and diffuse vimentin, with a majority showing CD34, bcl-2 and CD99 immunoreactivity; all cases tested were negative for S100 protein, cytokeratin, EMA, CAM5.2, smooth muscle actin, muscle specific actin, desmin, MYOD1, myogenin, CD117, GFAP, CD31, FVIII-RAg, collagen IV, p63, p53, calponin, caldesmon, CD56, NFP, and ALK-1. The principle differential diagnoses include pleomorphic adenoma, myoepithelioma, nodular fasciitis, schwannoma, fibromatosis coli, spindle cell “sarcomatoid” carcinoma, and spindle cell melanoma. All patients were managed with surgery, while two patients also received radiation therapy. Metastatic disease was identified in one patient immediately after excision. All patients with follow-up were alive without evidence of disease (n = 18), but the average follow-up is only 1.9 years. One patient is alive with disease at 12 months. Parotid gland SFT is a rare tumor, usually presenting in middle aged adults as a slowly growing mass. Characteristic histologic appearance with CD34 and bcl-2 immunoreactivity support the diagnosis. Surgery is the treatment of choice to yield a good outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Soft tissue lesions of the head and neck, and specifically of the salivary gland, are quite uncommon. More specifically, soft tissue tumors of the parotid gland are rare, but encompass very distinctive histologic lesions. One of these tumors is solitary fibrous tumor (SFT). SFT is a usually encapsulated, non-metastasizing lesion, considered to be part of the solitary fibrous tumor-hemangiopericytoma spectrum. This tumor has been referred to by numerous other names (localized fibrous tumor, localized fibrous mesothelioma, localized mesothelioma, solitary fibrous mesothelioma, and others), most of which are now outdated because they incorrectly suggested that the tumor was of mesothelial origin. “Solitary fibrous tumor” is the currently preferred term. While SFT is most common in the pleura, it may occur in any anatomic site, with about 6% developing in the head and neck [1]. SFT of the parotid gland is rare, with only a few cases reported in the English literature (Table 1) [2–20]. The dearth of these tumors may result in their misclassification and subsequent inappropriate management. This report focuses on the clinical presentation, histologic features, immunohistochemical profiles, and therapeutic approaches of SFT of the parotid gland in relation to patient management and outcome and a comparison to the differential diagnosis set in the context of a case report.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old man presented with a 10 years history of a mass in the left face-parotid gland region. The mass was felt to be slowly increasing in size, especially over the past several months. There was a history of recent trauma, and the lesion seemed to have increased in size thereafter. By physical exam, there was an approximately 4.5 cm palpable, firm, immobile, smoothly contoured mass without overlying erythema. There was no nerve paralysis or paresthesia. There were no constitutional symptoms (weight loss, fever, chills, night sweating, weight loss). The patient had hypertriglyceridemia, glucose intolerance, occipital neuralgia, migraine headaches, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and obesity (BMI = 35.4). He had never smoked, but did have an occasional beer.

A computed tomography scan of the head and neck revealed a well defined, heterogeneously enhancing 3.8 cm mass within the superficial portion of the left parotid gland (Fig. 1). The tumor showed variable attenuation, with central areas of decreased attenuation. No calcifications were seen. The deep lobe of the parotid gland was unremarkable.

A fine needle aspiration was performed. The smears were hypercellular with sheets and three dimensional clusters of monomorphic fusiform to spindled cells (Fig. 2). The nuclei were round and regular with delicate to coarse, evenly distributed nuclear chromatin (Fig. 3) and inconspicuous nucleoli. Intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions were noted. A number of capillaries were noted coursing through the three dimensional tissue fragments. A few isolated bipolar cells could be seen in the background. No chondroid-fibrillar material or myxoid stroma was present in the background. However, wispy, collagenous material was noted. Blood was present, but it was not disproportionate to the tumor cellularity. The cells were cohesive and clustered, but a true epithelioid appearance was not appreciated. The morphology was that of a spindled neoplasm, with a monomorphic adenoma, cellular pleomorphic adenoma, myoepithelioma, and schwannoma considered. A diagnosis of cellular pleomorphic adenoma was favored, and an excision planned.

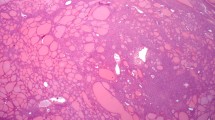

A superficial parotidectomy was performed without complications, although a branch of the facial nerve was felt to be trapped within the capsule of the tumor. Nerve stimulation was performed without sacrificing the nerve to achieve resection, although resulting in a positive resection margin. The gland measured 6.3 × 3.6 × 2.4 cm. Serial sections revealed a well circumscribed 4.3 × 3.1 × 2.5 cm tumor, identified on the inked margin. The tumor was pale to tan, with a generally fibrous, firm to rubbery consistency. By histologic examination, there was only isolated salivary gland parenchyma in the background, with tumor present at the borders of the sample. The tumor was well circumscribed, but showed an irregular capsule, with pseudopodial extensions of the process into the adjacent parotid gland parenchyma (Fig. 4). The neoplasm was composed of a variegated cellular mesenchymal proliferation of bland spindle-shaped cells lacking any pattern of growth and associated with “ropey” keloidal collagen bundles and delicate, interlaced thin-walled vascular spaces (Fig. 5). There was a general biphasic appearance to the tumor. First, there was a population of densely packed, short fascicles of a spindled cell population. These cells were relatively uniform with very ill defined cell boundaries, giving a syncytial appearance. The nuclei were ovoid to vesicular with small nucleoli (Fig. 6). Mitoses were noted, with 2 per 10 high power fields; Fig. 7 [50 high power fields examined; 40× objective lens with a 10× eyepiece using Olympus BX40 microscope]). Atypical mitoses (defined by abnormal chromosome spread, tripolar or quadripolar forms, circular forms, or indescribably bizarre) were not identified. The second population yielded a much more heavily collagenized appearance. These areas also had a similar spindled cell population, but were associated with a hemangiopericytoma-like vasculature, creating open patulous spaces. There were also extravasated erythrocytes, mast cells and rare tumor giant cells (Fig. 8). The background stromal collagen was wiry or ropy, heavily deposited in some areas and scant to absent in others (Fig. 5). The two components were intimately blended with one another. Specifically, there was no evidence of destructive growth, necrosis or cellular pleomorphism.

The lesional cells showed strong and diffuse cytoplasmic reactivity with CD34 (Fig. 8), bcl-2 (Fig. 8), CD99, and vimentin (Fig. 9), but were negative with CD68, S100 protein, cytokeratin, EMA, CAM5.2, smooth muscle actin (Fig. 9), muscle specific actin, desmin, MYOD1, myogenin, CD117, GFAP, CD31, Factor VIIIRAg, p63, p53, CD56, NFP, and ALK-1. Less than 1% of the lesional cells were stained by Ki-67. Based on the histologic appearance and immunohistochemistry profile, a diagnosis of SFT was made.

At last follow-up (9 months), the patient is without complications and disease free.

Materials and Methods

A review of the English literature based on a MEDLINE search from 1960 to 2011 was performed and all cases of solitary fibrous tumor involving the parotid specifically were included in the review, the majority of which were single case reports [2–20]. Clinical series of “head and neck soft tissue tumors” were selected if critical information about parotid gland SFTs were included (Tables 1, 2). Foreign language articles were only included if they were published alongside an English translation [11, 16] and articles with limited or lacking information or duplicate publications were excluded [21, 22].

Immunophenotypic analysis was performed by a standardized BenchMark-XT™ method employing 4 μm-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections. Table 3 documents the pertinent, commercially available immunohistochemical antibody panel used. When required, cellular conditioning for antigen retrieval was performed by various standardized retrieval techniques, as standardized and validated in our laboratory. Standard positive controls were used throughout, with serum used as the negative control. The antibody reactions were described as either positive or negative; nuclear, cytoplasmic, membranous or combination; and a percentage reported for the Ki-67 antibody.

Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square tests to compare observed and expected frequency distributions. Comparisons of means between groups were made with independent two tailed t tests. The alpha level was set at P < 0.05.

Discussion

Definition and Nomenclature

SFT was initially described in the pleura by Lietaud in 1767, followed in 1870 by Wagner [23] who noted the localized nature of the lesion. However, in 1931, Klemperer and Rabin classified pleural tumors into two types: diffuse mesotheliomas and localized mesotheliomas or SFT [24]. For some time, it was incorrectly supposed that the tumor was of mesothelial origin giving rise to names such as localized fibrous mesothelioma, localized mesothelioma, and solitary fibrous mesothelioma [25]. However, it was later demonstrated that this neoplasm was of mesenchymal origin, probably from adult mesenchymal stem cells, developing in almost any anatomic site [12, 26, 27]. For these reasons, SFT is now the preferred term [25, 28].

There is a significant morphologic overlap between SFT and hemangiopericytoma which has caused considerable debate as to what exactly constitutes SFT [28, 29]. Gengler & Guillou have come to the conclusion that most tumors that had been diagnosed as hemangiopericytoma in the past (with the exception of myopericytoma, infantile myofibromatosis, and the HPC-like tumors of the sinonasal tract that show myoid differentiation: glomangiopericytoma [30]) were not truly of pericytic origin, but instead constitute a cellular variant of SFT [29]. They suggest the use of the term “cellular SFT” to refer to these non-pericytic hemangiopericytomas and the use of the term “fibrous SFT” to refer to the classic SFT [29].

The fibrous variant of SFT is characterized by fibrous hypocellular areas that alternate with hypercellular areas composed of round-to-spindle cells with a fascicular, storiform, or fibrosarcoma-like arrangement. A distinguishing characteristic of fibrous SFT is the presence of numerous, medium-sized, ramified vessels with thickened and hyalinized walls [29]. According to the World Health Organization Classification of Tumours, there is also overlap between SFT and both lipomatous hemangiopericytoma and giant cell angiofibroma [28]. However, neither of these patterns of growth are yet recognized in the salivary gland. All of the SFTs described in this paper were of the “fibrous variant.”

Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation

SFT is a rare tumor, but is exceptionally rare in the parotid gland. The cause of the tumor is not clear [13]. In this case presentation, recent trauma brought the patient to clinical attention. However, he had a 10 years history of a parotid gland mass, so it seems unlikely that trauma is a true etiologic factor. While the histogenesis is still unproven, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural examination have shown that SFT is most likely derived from adult mesenchymal stem cells [12, 26].

Throughout the body, as well as in the head and neck region, SFT affects males and females with the same frequency [1, 8, 16, 29]. Similarly, patients with parotid gland SFT were equally divided between male (n = 11) and female (n = 11) (Table 2) [2–20]. SFT usually affects middle aged adults, but it has also been found in young patients [1, 8, 18, 29]. Patients with SFT of the parotid gland ranged in age from 11 to 79 years with an average age and median age of 51.2 and 49.5 years, respectively (Fig. 10) [2–20]. There was no significant difference (P = 0.93) between the average age at presentation of males (51.5 years) versus females (50.8 years).

Patients with SFT of the parotid gland present with a well defined, palpable, slowly growing, painless mass which has often been present for a significant duration (range, 3–120 months; mean, 24.7 months) [2–20, 28]. There was no significant difference in average duration of symptoms between males (mean, 32.6 months) and females (mean, 15.7 months) (P = 0.30) nor between left (mean, 29 months) or right sided tumors (mean, 16.2 months) (P = 0.46). Interestingly, patients often reported sleep apnea, as did our patient, suggesting the potential of parapharyngeal extension from the parotid gland or possibly compression symptoms related to nerve entrapment [10, 14, 28]. On rare occasions, especially in patients with large tumors, SFT may cause hypoglycemia, arthralagias, osteoarthropathy, and clubbing due to the production of an insulin-like growth factor that resolves upon tumor removal [13, 31]; these findings have not been reported in parotid gland SFT. Although 68.4% (n = 13) of parotid gland tumors were found on the left and 31.6% (n = 6) on the right, this was not a statistically significant finding (P = 0.11).

Radiographic Findings

In general, imaging of SFTs is nonspecific and most SFTs appear as a well-circumscribed to lobulated mass [13]. Computed tomography images tend to show a hypointense (to muscle) mass, which shows heterogeneous enhancement after contrast administration [8]. Magnetic resonance shows an isointense (to muscle) mass on T1 weighted images, while showing enhancement on T2 weighted images, especially with gadolinium contrast administration [8, 14, 15, 18, 32]. There were frequently heterogeneous streaks within the tumor, perhaps as a result of the rich vascular supply.

Pathologic Features

Macroscopic

In general, SFT is described as a firm, well circumscribed, often partially encapsulated neoplasm with a smooth, white surface with translucent areas [16, 28, 29]. The median size of extrapleural SFT is between 5 and 8 cm [28], while parotid gland tumors range from 1 to 12 cm, with a mean size of 4.5 cm (Table 2). There was no significant difference of tumor size between males and females (4.8 vs. 4.1 cm; P = 0.56). All the parotid tumors were described grossly as well circumscribed with the exception of one of the malignant tumors [11]. The tumors were partially to fully encapsulated. The tumors were grossly described as firm, white-tan or gray masses. Bone remodeling due to pressure erosion was reported in two cases [8, 14]. The tumors were identified in the superficial lobe (n = 7) more often than the deep lobe (n = 3), although this was not a statistically significant difference (P = 0.53), especially without complete data reported.

Microscopic

The histologic and immunophenotypic features of SFT are similar no matter the anatomic site affected [2, 6, 7, 28]. There are a variety of histologic features accepted as diagnostic criteria, including alternating hypercellular and hypocellular to fibrous areas. The tumor cells are arranged in fascicular, storiform or fibrosarcoma-like patterns, with numerous medium-sized ramifying vessels. The vessels may have thickened or hyalinized walls. The tumor cells are round to spindled with a predominantly fusiform appearance. The centrally placed nuclei are round to oval with open, vesicular nuclear chromatin distribution. Intranuclear pseudoinclusions of cytoplasmic material (pseudoinclusions) may be seen. A number of additional features can be seen, including stromal myxoid change, inflammatory cells, especially mast cells, and isolated multinucleated stromal tumor giant cells. No chondroid or mucinous material was identified in the background.

Several parotid gland SFTs demonstrated focally entrapped normal salivary gland acini and ducts at the edge [7]. This should not be over interpreted to represent invasion. The tumors were cellular, arranged in haphazard short interlacing fascicles of spindled to epithelioid cells. The spindled cells showed tapering cytoplasm with monotonous, round to oval nuclei with delicate to coarse even nuclear chromatin distribution. Keloid-like to wavy collagen was deposited between the neoplastic cells. Necrosis was not present, but mitoses could be seen. While mitotic counts could be high (up to 8 per 10 high power fields [20]), in general >6 mitoses/10 HPFs were present in tumors which were identified as malignant [11, 20]. However, there are too few cases to suggest a definitive correlation between mitotic index and malignant behavior. The tumors in this series were fibrous-type SFT, and so, while vessels are present within the tumor, they are not a dominant pattern as can be seen in the cellular-type SFT [29].

By current standards, there is no consistent way to predict malignant SFT [27, 28]. Tumors possessing histologically malignant features such as high cellularity, pleomorphism, necrosis, high mitotic rate, and/or infiltrative margins are more likely to behave aggressively than benign looking lesions, but histologic features do not reliably predict aggressive clinical behavior [11, 16, 20, 28]. Three parotid tumors were described as malignant, showing marked nuclear pleomorphism, atypical mitoses, and increased mitoses, but none of them showed necrosis. The first of these histologically malignant tumors metastasized to the lungs before it was diagnosed, and the second tumor formed two nodules in the parotid gland; the authors are unaware of whether or not the third tumor behaved aggressively [11, 16, 20]. However, tumors which did not have increased mitoses, pleomorphism or high cellularity did not behave in an aggressive fashion.

Immunohistochemistry

SFT appears to have a characteristic immunophenotype regardless of its location in the body [6]. The neoplastic cells show nearly uniform reactivity with vimentin and CD34, while the vast majority of cases also stain with bcl-2 and CD99. CD34 is the most important and sensitive marker for the diagnosis of SFT, although it may not be positive in all cases [2, 9, 18]. Interestingly, malignant SFT tends to show reduced CD34 reactivity when compared to benign tumors [29]. As shown in Table 4, a number of markers tested were negative [2–14, 16, 18–20]. Specifically, in the differential diagnosis in the parotid gland, the lack of S100 protein, cytokeratin, EMA, CAM5.2, p63, desmin, smooth muscle actin, muscle specific actin, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, and CD117 will help with the differential diagnoses considered.

Cytology

Diagnosis of SFT based on fine needle aspiration results alone, especially in the parotid gland, is very challenging [3, 19]. Based on the hypercellular smears, capillary vascular component, delicate nuclear chromatin distribution, and intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions and a lack of myxoid-chondroid matrix material, the diagnosis can at least be raised in the differential of a spindle cell tumor. In general, as long as a diagnosis of “neoplasm” is used, whether primary salivary gland epithelial neoplasm or mesenchymal neoplasm, the appropriate surgical management will be implemented.

Differential Diagnosis

Solitary fibrous tumor shows a wide spectrum of histologic features, which frequently leads to a broad differential diagnosis and frequent misdiagnosis [4, 7]. A number of lesions are considered in the differential based on pattern of growth, including cellular pleomorphic adenoma, myoepithelioma, schwannoma, neurofibroma, fibrous histiocytoma, nodular fasciitis, fibromatosis, myofibroblastoma, meningioma, fibrosarcoma, spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma, spindle cell melanoma, Kaposi sarcoma, monophasic synovial sarcoma, and even unusual tumors like metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors or mesothelioma. Needless to say, this is a broad reactive and neoplastic differential diagnostic group. For the most part, the characteristic histologic features of a bland spindle cell population arranged in a patternless to fascicular architecture, with heavy, wiry, keloid-like collagen deposition in association with a rich vascular plexus can help to confirm the diagnosis, along with a limited, pertinent and focused immunohistochemistry panel. The presence of any epithelial markers (keratin, EMA, CK5/6, p63) and/or S100 protein will effectively eliminate many of the common salivary gland tumor mimics. GFAP is often positive in pleomorphic adenoma, and would be of additional assistance in excluding this diagnosis. Beta-catenin is positive in fibromatosis. EMA highlights meningioma. Melanoma would react with HMB45, Melan-A, tyrosinase and S100 protein. Kaposi sarcoma usually shows HHV8 immunoreactivity. Synovial sarcoma would be positive with epithelial markers, as well as TLE1; CD99 would not help, as it is frequently positive in both tumor types. Up to 18% of cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma (dermatofibroma) will show CD34 immunoreactivity [33], but usually the pattern of growth and collagen deposition will be different. Nodular fasciitis tends to have a rapid clinical presentation, a tissue-culture-like growth, extravasated erythrocytes, giant cells and keloid-like collagen deposition, while lacking CD34 and bcl-2 immunoreactivity [34]. Schwannoma is strongly reactive with S100 protein, while lacking CD34. Metastatic GIST would usually have a clinical history, show a high mitotic index, and have CD117 immunoreactivity. Mesothelioma shows epithelial markers, along with calretinin and CD15, markers negative in SFT.

Treatment and Prognosis

The most common treatment for both benign and malignant SFTs is complete local surgical excision with negative microscopic margins if feasible [2–20, 35, 36]. Because SFTs are often highly vascular, the possibility of profuse bleeding must be kept in mind when resecting the tumor [13], with preoperative embolization employed in some patients. Since the literature shows a bias to single case reports, the overall follow-up time is short (mean, 1.8 years), with 6 years the longest follow-up duration. Only a single patient had persistent disease at 12 months. All of the remaining patients were alive without evidence of disease at last follow-up (n = 18; mean: 1.9 years).

Cox et al. have stated that there is currently no evidence that malignant SFTs require additional treatment beyond excision, so long as they have been completely excised, the most important factor in clinical outcome [1, 16, 35, 37]. However, for the cases of parotid gland SFT that reported a positive margin, including our case, there has been no recurrence to date, although longer follow-up data is required to make a more meaningful comment [2, 35]. Others have documented recurrence decades after the primary at other extrapleural sites [1, 31]. Therefore, close clinical and radiographic follow-up are suggested to exclude recurrence or metastatic disease [9, 11, 16, 18, 28, 29]. Tumors that cannot be completely excised or which show malignant histologic features may respond to radiation and/or chemotherapy [20, 31], but with only isolated reports, this remains to be confirmed.

Conclusion

SFT of the parotid gland is an extremely rare neoplasm which occurs most often in middle aged patients, without a gender selection, who have symptoms of a mass lesion for many months. Diagnosis of SFT is based on classical histologic and immunophenotypic features (CD34, bcl-2), that allow for distinction and separation from other tumors in the differential diagnosis. Limited follow-up suggests a good prognosis whether the tumors are histologically benign or malignant when managed by complete surgical excision.

References

Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hajdu C, Ferrone CR, Hussain M, Lewis JJ, et al. Clinicopathologic correlates of solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer. 2002;94:1057–68.

Brunnemann RB, Ro JY, Ordonez NG, Mooney J, El-Naggar AK, Ayala AG. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 24 cases. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:1034–42.

Cho KJ, Ro JY, Choi J, Choi SH, Nam SY, Kim SY. Mesenchymal neoplasms of the major salivary glands: clinicopathological features of 18 cases. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265(Suppl 1):S47–56.

Ferreiro JA, Nascimento AG. Solitary fibrous tumour of the major salivary glands. Histopathology. 1996;28:261–4.

Gerhard R, Fregnani ER, Falzoni R, Siqueira SA, Vargas PA. Cytologic features of solitary fibrous tumor of the parotid gland. A case report. Acta Cytol. 2004;48:402–6.

Guerra MF, Amat CG, Campo FR, Perez JS. Solitary fibrous tumor of the parotid gland: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:78–82.

Hanau CA, Miettinen M. Solitary fibrous tumor: histological and immunohistochemical spectrum of benign and malignant variants presenting at different sites. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:440–9.

Kim HJ, Lee HK, Seo JJ, Kim HJ, Shin JH, Jeong AK, et al. MR imaging of solitary fibrous tumors in the head and neck. Korean J Radiol. 2005;6:136–42.

Kumagai M, Suzuki H, Takahashi E, Matsuura K, Furukawa M, Suzuki H, et al. A case of solitary fibrous tumor of the parotid gland: review of the literatures. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2002;198:41–6.

Manglik N, Patil S, Reed MF. Solitary fibrous tumour of the parotid gland. Pathology. 2008;40:89–91.

Messa-Botero OA, Romero-Rojas AE, Chinchilla Olaya SI, az-Perez JA, Tapias-Vargas LF. Primary malignant solitary fibrous tumor/hemangiopericytoma of the parotid gland. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2011;62:242–5.

Mohammed K, Harbourne G, Walsh M, Royston D. Solitary fibrous tumour of the parotid gland. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:831–2.

Ridder GJ, Kayser G, Teszler CB, Pfeiffer J. Solitary fibrous tumors in the head and neck: new insights and implications for diagnosis and treatment. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116:265–70.

Sato J, Asakura K, Yokoyama Y, Satoh M. Solitary fibrous tumor of the parotid gland extending to the parapharyngeal space. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;255:18–21.

Sreetharan SS, Prepageran N. Benign fibrous tumour of the parotid gland. Asian J Surg. 2005;28:45–7.

Suarez Roa ML, Ruiz Godoy Rivera LM, Meneses GA, Granados-Garcia M, Mosqueda TA. Solitary fibrous tumor of the parotid region. Report of a case and review of the literature. Med Oral. 2004;9:82–8.

Takahama A Jr, Leon JE, de Almeida OP, Kowalski LP. Nonlymphoid mesenchymal tumors of the parotid gland. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:970–4.

Thompson M, Cheng LH, Stewart J, Marker A, Adlam DM. A paediatric case of a solitary fibrous tumour of the parotid gland. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:481–7.

Wiriosuparto S, Krassilnik N, Bhuta S, Rao J, Firschowitz S. Solitary fibrous tumor: report of a case with an unusual presentation as a spindle cell parotid neoplasm. Acta Cytol. 2005;49:309–13.

Yang XJ, Zheng JW, Ye WM, Wang YA, Zhu HG, Wang LZ, et al. Malignant solitary fibrous tumors of the head and neck: a clinicopathological study of nine consecutive patients. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:678–82.

Orvidas LJ, Kasperbauer JL, Lewis JE, Olsen KD, Lesnick TG. Pediatric parotid masses. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:177–84.

Thompson M, Cheng LH, Stewart J. Solitary fibrous tumour of the parotid gland. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:319.

Wagner E. Das tuberkelahnliche lymphadenom (der cytogene oder reticulirte tuberkel). Arch Heilk (Leipig). 1870;11:497.

Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol. 1931;11:385–412.

Chan JK. Solitary fibrous tumour–everywhere, and a diagnosis in vogue. Histopathology. 1997;31:568–76.

Rodriguez-Gil Y, Gonzalez MA, Carcavilla CB, Santamaria JS. Lines of cell differentiation in solitary fibrous tumor: an ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of 10 cases. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2009;33:274–85.

Fletcher CD. The evolving classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the new WHO classification. Histopathology. 2006;48:3–12.

Guillou L, Fletcher JA, Fletcher CDM, Mandahl N. Extrapleural solitary fibrous tumour and haemangiopericytoma. In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. p. 86–90.

Gengler C, Guillou L. Solitary fibrous tumour and haemangiopericytoma: evolution of a concept. Histopathology. 2006;48:63–74.

Thompson LD, Miettinen M, Wenig BM. Sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic analysis of 104 cases showing perivascular myoid differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:737–49.

Goodlad JR, Fletcher CD. Solitary fibrous tumour arising at unusual sites: analysis of a series. Histopathology. 1991;19:515–22.

Jeong AK, Lee HK, Kim SY, Cho KJ. Solitary fibrous tumor of the parapharyngeal space: MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:473–5.

Rudolph P, Schubert B, Wacker HH, Parwaresch R, Schubert C. Immunophenotyping of dermal spindle cell tumors: diagnostic value of monocyte marker Ki-M1p and histogenetic considerations. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:791–800.

Thompson LD, Fanburg-Smith JC, Wenig BM. Nodular fasciitis of the external ear region: a clinicopathologic study of 50 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2001;5:191–8.

Cox DP, Daniels T, Jordan RC. Solitary fibrous tumor of the head and neck. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110:79–84.

Suster S, Nascimento AG, Miettinen M, Sickel JZ, Moran CA. Solitary fibrous tumors of soft tissue. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1257–66.

England DM, Hochholzer L, McCarthy MJ. Localized benign and malignant fibrous tumors of the pleura. A clinicopathologic review of 223 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:640–58.

Acknowledgments

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Southern California Permanente Medical Group or The Permanente Medical Group. There is no financial conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bauer, J.L., Miklos, A.Z. & Thompson, L.D.R. Parotid Gland Solitary Fibrous Tumor: A Case Report and Clinicopathologic Review of 22 Cases from the Literature. Head and Neck Pathol 6, 21–31 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-011-0305-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-011-0305-8