Abstract

The purpose of the present study is to contribute to the gap in the literature by investigating the sexting behaviors of adolescents under the age of 18 and how these behaviors are related to internet related problems. Using data collected from high school students in a rural county in western North Carolina, results indicated that deviant peer association and Internet-related problems were in fact associated with sexting by juveniles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term sexting generally refers to the sending and/or receiving of sexually suggestive or sexually explicit images (usually nude or semi-nude photos), from one cell phone to another (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010; Judge, 2012; Lenhart, 2009; Mitchell, Finkelhor, Jones & Wolak, 2012). While the issue of sexting is one that has received a fair amount of recent media attention, to include numerous internet surveys and polls (Cox Communications, 2009; MTV-AP, 2009; The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy and Cosmogirl.com, 2008), scholarly research in this area remains limited. In particular, theoretically informed research on sexting focusing specifically on adolescents (under age 18) is scant. As such, the current study seeks to shed light on this topic, drawing upon contributions from Akers (1998) Social Learning Theory, as well as existing literature centered on the conceptualization of Internet-related problems in order to develop a more grounded approach to understanding youth sexting behaviors.

To be sure, ongoing discourse concerning the appropriateness of labeling sexting as a form of deviant behavior is a critical issue to address, especially given the theoretical backdrop to the current study. It has been argued by some that sexting should be viewed as a legitimate means of intimate expression or sexual experimentation between consenting individuals (Lee, Crofts, Salter, Milivojevic, & McGovern, 2013; Shafron-Perez, 2009). While certainly, this practice may on the surface appear harmless, and in some contexts encouraged among adults (Lee et al. 2013), it remains nonetheless a ‘risky’ behavior even among this age-group, as images sent can easily be saved indefinitely on the recipients electronic device (cell phone, tablet etc.), forwarded to others, and even posted on social media websites without the consent or knowledge of the sender (Ling & Yttri, 2005; Wastler, 2010).

For adolescents however, the risks associated with sexting include an array of legal consequences not applicable to adults, specifically when the sext involves an image of someone under the age of 18 (Klettke et al. 2014). There are in fact several instances in which youth who have engaged in this practice have been referred to the courts, charged with offenses related to the possession and distribution of child pornography (Barkacs & Barkacs, 2010; Hinduja & Patchin, 2010). Though this response may seem harsh to some, it remains a very real consequence in various states. Even those states reducing the severity of charges against adolescents for sexting behaviors (Lenhart, 2009), most still allow for misdemeanor charges. This applies particularly to youth who forward on sexts they receive depicting persons other than themselves without permission, or who posts these images on social networking sites without the knowledge or permission of the person depicted in the image (Barkacs & Barkacs, 2010). For example, Wolak, Finkelhor, and Mitchell (2012) conducted a survey utilizing a stratified sample of U.S. law enforcement agencies (N = 2,700). Results indicated that between 2008 and 2009, approximately 3,477 cases of youth sexting were investigated. While some involved the transmission of youth images to adult recipients, when isolating those cases occurring between youth only, arrests resulted for 18 % of cases.

Ultimately, the critical issue from the legal standpoint involves the transmission of sexually explicit photos of youth, a practice which has long been legally prohibited via pornography statutes (18 U.S.C. § 2,251). While perhaps legal consequences for youth who willingly send nude or semi-nude images of themselves to another could be viewed as falling outside the scope or ‘spirit’ of child pornography laws, there have been studies to-date documenting the prevalence of youth forwarding on such images to other, unintended recipients (Ostrager, 2010; Peskin et al., 2013; Strassberg et al., 2013). Moreover, Strassberg et al. (2013) found that about 58 % of the youth in their survey were in fact aware of the potential for very serious legal consequences of sexting, with youth who had reported they had engaged in sexting more likely to recognize some legal consequence for sexting than those who never sexted.

In sum, while the argument could (and has) been made that sexting by youth represents a “subterranean expression” (Lee at al., 2013) of a behavior that is widely accepted, albeit somewhat risky, when engaged in by adults, and therefore should not be viewed as criminal or deviant, the legal reality of sexting in which youth are the subject of sexually explicit images is clearly quite different. Moreover, youth tend to be aware of these legal consequences, but are nonetheless engaging in such behavior anyway. Ultimately, the current legal realities of youth sexting allow for the behavior to be considered deviant when engaged in by youth.

It should be noted also, that in addition to these potential legal consequences for youth, studies have also suggested that many youth suffer various degrees of social and emotional consequences, particularly in cases where photos are forwarded to other students/classmates, or posted on social networking sites (Barak, 2005; Barkacs & Barkacs, 2010; Hinduja & Patchin, 2010; Judge, 2012; Strassberg, McKinnon, Sustaita, & Rullo, 2013). Often, the subjects of these photos experience ridicule, bullying and other forms of peer ostracizing. Results from a study conducted by Reyns, Burek, Henson,and Fisher (2011), further supported that youth who sext experienced various unintended consequences. For instance, they found that when controlling for a set of behavioral and demographic characteristics, youth who engage in sexting had an increased likelihood of cyber victimization, particularly for females. For the purposes of their study, cyber victimization included instances of being contacted by individuals via digital technology after asking them to stop, being harassed, receiving unwanted sexual advances or being threatened with violence. While this study is unique in its exploration of a correlation between sexting and future victimization, there have been several news events reporting on this issue. In one severe case, 18 year old Jessica Logan committed suicide after several months of social and emotional bullying from peers after a sext of Jessica was forwarded all around her school. For these reasons, sexting in this context has been considered by some a form of cyberbullying (Dake, Price, & Maziarz, 2012; Dilberto & Mattey, 2009; Smith et al., 2008). Thus, while instances such as these may be infrequent and extreme, they nonetheless suggest the potential for psychosocial risks and consequences associated with sexting (Strassberg et al., 2013).

Given the potential legal and psychosocial consequences of sexting by adolescents discussed above, it is essential this issue be studied in more detail by scholars as a form of youth deviance. As such, the current study seeks to explore further, the extent of sexting among adolescents, specifically high school students. Moreover, we hope to identify correlates to sexting behavior among this demographic. Drawing upon Akers (1998) Social Learning Theory, suggesting that a key element to the learning of deviant behaviors is the association with deviant peers, the current study attempts to identify if youth who score high on measures of deviant peer association are more likely to engage in sexting than those who do not. In addition, as there is some evidence suggestive of a link between sexting and an overall increased frequency of texting (Dake et al., 2012), as well as a link between sexting and time spent engaging in other online activities (Cox Communications, 2009), the current study seeks to determine if a correlation can be found between existing measures of internet related problems (Armstrong, Phillips, & Saling, 2000) and sexting.

The Nature and Extent of Sexting among Adolescents

Much of the initial attention brought to youth sexting seems to be a result of the combined effects of some high profile cases, like that of Jessica Logan discussed above, along with a few widely cited online polls regarding sexting behavior (Lenhart, 2009). One of the first national studies of sexting was conducted by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and unplanned Pregnancy and Cosmogirl.com (2008). This online poll surveyed both teens and young adults, finding that about 20 % of the 653 13–19 years old reported having sent or posted a nude/semi-nude photo of themselves electronically, typically to a boyfriend/girlfriend, or someone they were dating or interested in dating. For the purposes of their study, this figure includes images sent via text, email, or instant message. Moreover, the poll further indicated that 38 % of teen girls, and 39 % of teen boys have been shown sexts originally intended for someone else, suggesting the sharing and/or dissemination of sexts between ‘non-intimate’ peers is even more prevalent than initial creation of, and perceived intimate sharing of such images. Cox Communications (2009) conducted an internet poll for teens (13–19 years), focusing on internet use, cyberbullying and sexting. Results of this poll also indicated that about 1 in 5 teens engaged in sexting by either having sent or received a nude/semi-nude photo via text. MTV and Associated (2009) also released findings from a similar poll conducted in 2009. Contrary to the National Campaign and Cox Communications findings, the MTV findings suggested that only about 10% of respondents had sent a sext to someone else, but about 18 % reported receiving a sext. However, while the former two polls focused on teens specifically, and defined sexting as having sent sexually suggestive pictures via text or email, the MTV poll included young adults to age 24, and focused on nude photos (vs. nude or semi-nude).

While these polls generated much public interest and concern regarding the prevalence of sexting among adolescents, scholarly work in the area has been rather limited to date. There are however, a handful of studies worth noting, though the findings similarly varied in terms of providing any clear indication of the scope of teen sexting. One of the first and widely cited studies was conducted by the Pew Research Center (Lenhart, 2009). Data were collected on a national representative sample of youth ages 12–17 who owned cell phones in 2009. Of youth completing the survey, only 4 % reported having sent a sexually suggestive or nude/nearly nude photo of themselves to someone else. The study reported no variation by gender, with little variation by age—older youth slightly more likely to have sent a sext than younger youth in the study (8 vs. 4 % respectively). When asked about whether or not youth in the sample had received a sext, about 15 % reported they had. There was also more variation among age groups receiving sexts, again with older youth being more likely to have received a sext than younger youth.

Hinduja and Patchin (2010) conducted a study in which 4,400 youth were randomly selected from several individual schools within one larger public school district. Youth in this study were between 11 and 18 years old. Results from their study indicated a slightly higher proportion of youth (7.7 %) have sent a sext depicting images of themselves to others. Conversely, they found that a slightly lower proportion (12.9 %) had received a sexually explicit or suggestive image via cell. Like the Pew study, no gender variation was found among youth sending sexts, however boys were significantly more likely to receive them, and overall the likelihood of engaging in sexting increased with age. Overall, the authors suggest that while the results of their study and others vary, there remains a meaningful number of youth engaging in the practice.

Indeed, two years later, two studies in particular were conducted that seem to indicate the practice of sexting among adolescents may have increased quite a bit. Temple et al. (2012) and Dake et al. (2012) both found that at least among certain subgroups of youth, approximately 25 % or more were engaging in sexting. Temple et al. (2012) study was limited in its definition of sexting to include only the transmission of nude photos, omitting semi-nude or sexually suggestive/explicit. Of the 964, 14–19 years old respondents, 27.6 % reported sending naked photos. While again in this study no variation by gender was evident, the authors did find that for girls, there was a significant correlation between sexting and engaging in other ‘risky’ sex behaviors, including the use of drugs and/or alcohol prior to having sex. Dake et al. (2012), on the other hand, included images other than nude-only photos. Thirty-six middle schools and 26 high schools across 35 midwestern county schools were surveyed as part of the Center for Disease Control’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Results included data from 1,289 youth. In this study, 17 % of the respondents overall reported engaging in sexting, with no variation by gender. However, when the results were disaggregated by race/ethnicity, they found that sexting was more common among racial minorities, with 32 % of African American youth, 23 % of Hispanic youth, and 17 % of White youth reporting sexting behaviors. Like Temple et al. (2012), Dake et al. (2012) also found a correlation between sexting and other risky behaviors. For instance, those youth reporting they drank alcohol, or smoked marijuana were significantly more likely to sext than those who did not. Furthermore, Dake et al. (2012) also found that the more time a youth spent texting in general, the more likely he/she was to sext. This appears to support a finding from the Cox Communication (2009) poll, which found that youth who reported having engaged in sexting tend to spend more time online per week engaged in various activities related to social media and networking (Cox Communication, 2009).

Mitchell, Finkelhor, Jones, and Wolak (2012) utilized a cross-sectional, National phone survey to discuss sexting behaviors with 1,560 youth ages 10–17 who self-identified as internet users. Unlike any of the previous studies, Mitchell et al. (2012) conclude that the practice of sexting was not normative, with only 2.5 % of respondents indicating they had created or appeared in a nude or nearly nude picture, with this figure dropping to just 1 % if responses were limited to sexually explicit sexts. A slightly higher proportion (7.1 %) reported having received a nude or nearly nude photo of someone else, 5.9 % reporting receiving sexually explicit photos of others. However, as discussed by Strassberg et al. (2013), these overall prevalence figures are somewhat misleading, as specific age groups represented in the sample reported very different rates of sexting. Specifically, while less than 0.6 % of 10–12 year olds reported having sexted, youth between the ages of 15–17 were much more likely to sext, with 15 % of this group reporting having done so.

Considering the variation in definitions and sampling employed by the aforementioned studies, Strassberg et al. (2013) explored sexting behaviors by high school minors, operationalizing sexting as the transfer of sexually explicit photos via cell phone. While this study was limited to high school students recruited from a single private school in the Southwestern U.S., the researchers found that nearly 20 % of students reported having sent a sext, with a significantly higher proportion reporting they have received a sext. Having received a sext varied significantly by gender, with 30.9 % of females, and 49.7 % of males having received at least one. Unlike previous studies, Strassberg et al. (2013) explored the nature of the differential found between the sending and receiving of sexts found in their study. Interestingly, their findings tend to confirm previous suppositions that the sharing of sexts beyond the intended recipient is indeed taking place, as 27 % of males and 21.4 % of females indicated they had forwarded a sext they received to at least one other person, leading the authors to conclude that while the difference in proportions of youth sending vs. receiving texts may be in part attributed to youth sending sexts of themselves to more than one recipient, this difference is more likely attributed to the forwarding on of sexts.

Overall, the available research on sexting among adolescents is both limited and quite varied in its findings. In addition, each of the aforementioned studies varies in terms of the operational definition of sexting, and the age range of youth included in the samples. However, there seems to be some emerging patterns worth further exploration, or consideration. First, the two studies utilizing national samples of youth (Lenhart, 2009 & Mitchell et al., 2012) reported lower overall rates of youth sexting than those focusing on more localized geographic settings (Temple et al., 2012; Dake et al., 2012). This differentiation may be suggestive of some geographic variation in the rate of sexting. In terms of commonalities among findings, most studies show no significant variation by gender among those who create sexts depicting images of themselves; however, there is some indication males are more likely to receive sexts from others. Furthermore, each study finds that overall the proportion of youth receiving sexts from others is greater than the proportion of youth creating/sending them. This finding, along with those studies indicating a higher proportion of youth reporting having received a sext image that was not originally intended for them lends support for not only the legal concerns associated with youth sexting, but also the potential social/emotional consequences discussed earlier. Clearly the creation and sending of sext images exists beyond what could be considered the ‘voluntary’ transmission of images between individuals. As such, the association of some forms of sexting behavior with cyberbullying, or cybercrime more generally is not necessarily unfounded. What is needed, and is the focus of the current study, is more information on the prevalence of sexting among adolescents in order provide more clarity to the thus far, somewhat murky findings. Also, the existing studies do little to attempt to explain sexting behavior by drawing upon delinquency theory to identify possible correlates to this behavior, though some have found links between sexting and higher reports of texting in general, as well as the use of other means of social networking, in addition to some correlation between sexting and other delinquent (‘risky’) behaviors such as drinking and/or drug use. As such, the present study seeks to help fill this gap in the research by also seeking to shed light on the potential correlates of sexting behaviors by adolescents.

Deviant Peer Associations

Given the range of Internet and other technology related mechanisms (including cell phones/smartphones) that have allowed for various ‘new’ forms of deviance, several studies have sought to examine the ways in which criminological theory may assist in accounting for these behaviors. One theory that has long been associated with deviance, particularly among adolescents is Akers (1998) social learning theory. This theory posits that individuals learn deviant behavior in much the same way law-conforming behavior is learned. Specifically, it is argued that individuals become deviant through a dynamic social learning process that includes exposure to, and reinforcement of these behaviors by deviant peers. These associations include the learning of deviant definitions, deviant behavior modeling, and reinforcement of these behaviors and the justifications for them. Not only has deviant peer association been found to be a strong correlate for crime in general (Akers, 1998; Akers & Lee, 1996; Lee, Akers, & Borg, 2004), but has also been consistently linked to an array of cyberdeviance (Bossler & Burruss, 2010; Higgins, 2005; Higgens, Fell, & Wilson, 2006; Higgins & Makin, 2004a, 2004b; Holt, Bossler, & May, 2010; Wolfe & Higgins 2009). To-date however, the examination of social learning theory as it may specifically correlate to the cybercrime of sexting by adolescents has not yet been explored. As such, the current study draws upon this theory by measuring youths’ levels of deviant peer associations in order to determine if indeed it is correlated with sexting behavior.

Internet-Related Problems

A second body of literature exploring the extent and nature of what has been called “Internet Addiction” is also guiding the present study. Given the increasing accessibility individuals have to the Internet, as well as to other forms of technological communications, such as cell phones and smartphones, concerns over excess use and even abuse of these technologies have generated concern over the potential for individuals to develop internet related problems (e.g., a dependency upon these mechanisms) that in some ways mirrors other forms of addiction (Armstrong, Phillips, & Saling, 2000; Brenner, 1997; Goldberg, 1996; Griffiths, 1998; Shotton, 1991). Overall, these studies focused upon identifying the extent to which a ‘typical’ Internet or computer “addict” could be identified demographically, and produces very mixed results, suggesting anyone with access to these technologies could become dependent. Several studies also sought to adapt criteria from the DSM-IV for substance abuse, in order to determine if self-identified ‘Internet-addicts’ demonstrated behaviors similar to those experienced by substance abuse addicts, such as negative life consequences, withdrawal symptoms, academic/job failure or poor performance (Armstrong et al., 2000; Egger & Routerberg, 1996; Young, 1997; Brenner, 1997). Overall, findings seem to indicate some support for the existence of several negative social and familial or life consequences experienced by chemical addicts, among the samples engaging in heavy Internet use (Shotton, 1991; Young, 1997).

While the current study does not seek to identify or classify youth as Internet addicts, the aforementioned studies could provide some additional insight into the potential youth characteristics that may be associated with sexting. In particular, Armstrong et al. (2000) utilized several interrelated scales to measure Internet-addiction, one of which was the “Internet Related Problem Scale”. This scale included twenty questions related to tolerance, craving, withdrawal and negative life consequences with respect to excessive Internet use. Their results indicated a significant correlation between this scale and the total number of hours individuals spent online. Drawing upon these findings, the current research is interested in exploring if a similar relationship exists between Internet-related problems and sexting. Specifically, this study will utilize Armstrong et al., 2000) Internet-related problem scale in order to determine if youth who score higher on the Internet-related problem scale are more likely to also engage in sexting than those with lower Internet-related problem scales.

Present Study

Research has consistently indicated that individuals under the age of 18 are not only those who are most likely to be cyber victimized in multiple ways, but also have a high likelihood of perpetrating these types of crimes (Marcum, Higgins, Freiburger, & Ricketts, 2013). Furthermore, there is still a gap in the theoretical literature that provides support for an explanation of this behavior for this age group. The purpose of this study is provide a clearer picture of the amount of high school students who are participating in the cybercrime of sexting, as well as the correlates of such behaviors by drawing upon contributions from Akers (1998) social learning theory, as well as from the literature exploring measures of Internet-related problems, specifically contributions from Armstrong et al. (2000).

Methodology

Research Design

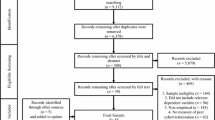

A rural county in western North Carolina was chosen to participate in the study. The Board of Education for that county gave approval for its students to participate. After obtaining Internal Review Board approval from the researcher’s university, the principals of four high schools in this county agreed to allow their students to participate on a voluntary basis. All 9th through 12th graders were recruited for the study. First, a consent form was sent home two weeks before administration of the survey to the parents and/or legal guardians of all the students, along with information about the study. By signing the consent form, parents had the opportunity to allow their child to participate in the study. At the time of survey administration, all children able to participate were given the survey with an assent form attached. Respondents were able to withdrawal from participation at any time. A total of 1,617 surveys were completed.

Measures

The measures for this study include items related to sexting, Internet-related problems, deviant peer association, as well as age, sex, race, and grade point average (GPA) as controls.

Sexting

Sexting is the dependent measure for the current study. Youth were asked if they had ever texted a nude/partially nude picture of themselves within the past year. This item is consistent with previous research in the area of sexting (Mitchell et al., 2012). The original answer choices for this item ranged from 1 (Never), to 5 (7+ times). The original answer choices result in non-normal data. To alleviate the non-normal data issue, the answer choices are collapsed into the dichotomous measure of either 0 (Never), or 1 (performed).

Internet Related Problems

To address our hypothesis that individuals who have Internet-related problems are more likely to engage in sexting, we used Armstrong, Phillips, & Saling’s, (2000) measure. This measure consists of 20-items that capture the concepts of tolerance, withdrawal, craving, and negative life consequences, and are consistent with the DSM-IV criteria for substance use. The items are scored using a 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Not true at all) to 10 (extremely true); thus, higher scores on the scale indicate more Internet related problems. The internal consistency of scale is acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94).

Deviant Peer Association

Drawing upon social learning theories of deviance, in particular Sutherland’s (1939) differential association theory, we would expect that sexting is not only a learned behavior, but one that is perhaps reinforced by peer associations. Indeed, the Pew study (Lenhart, 2009) found, through focus groups with youth study participants, that many stated they engaged in sexting either because friends of theirs had done so, or as a result of peer pressure. Thus, in viewing sexting as a form of youth deviance, we might also expect that youth who associate with deviant peers generally will be more likely to sext than those who do not. As such, to address our second hypothesis that individuals who associate with with deviant peers are more likely to engage in sexting, we include an expanded measure to capture multiple forms of crime and deviance. The measure seeks to capture the number of peers respondents associate with who engage in various deviant/delinquent activities within the past year. As such, youth in the study were asked: How many of your friends performed the following behavior in the past year: 1) texted a nude/partially nude picture, 2) used another person's debit/credit care without his/her permission, 3) used another person's license/ID card without his/her permission, 4) logged into another person's email without his/her permission and sent an email, 5) logged into another person's Facebook and posted a message, 6) accessed a website for which you were not an authorized user, 7) illegally downloaded a song or album from the Internet, 8) illegally downloaded software from the Internet, 9) illegally downloaded a movie from the Internet, 10) copied a music CD, 11) copied a software license, 12) copied a DVD, 13) repeatedly contacted someone online event after they requested he/she stop, 14) threatened another individual with violence online, and 15) repeatedly made sexual advances at someone. The respondents marked their responses using a 5-point Likert-type scale, with responses ranging from 1 (None) to 5 (all of them). Higher scores on the scale indicate greater association with deviant peers. The internal consistency for this measure is acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95).

Control measures

Finally, a number of controls were used for the current study, including the youths’ age, race, gender, and GPA. Respondents were asked to report their current age, which is included as a continuous measure. Race is measured as a dichotomous variable, with 0 (non-white) and 1 (white). Gender is also a dichotomous measure, with 0 (female) and 1 (male). Finally, GPA is captured by the respondent’s self-reported current GPA.

Analysis Plan

The analysis plan incorporated two steps. The first step is a presentation of the descriptive statistics. The descriptive statistics provide some indication of the distribution of the data. The second step is the use of multiple regression. Multiple regression is an analysis technique that uses a set of independent measures (i.e., low Internet-related problems, deviant peer association, age, sex, race, and GPA) to predict or correlate to a dependent measure (i.e., Sexting) (Freund & Wilson, 1998). In this study, the dependent measure is dichotomous, and this makes the use of Ordinary Least Squares regression improper. Using OLS in this situation violates the assumption of continuous dependent measures (Lewis-Beck, 1979). In this study, binary logistic regression is the proper technique. While binary logistic regression is the proper technique, as with any form of multiple regression, multicollinearity is a potential problem. Fruend and Wilson (2002) argue that tolerance levels that 0.20 and below indicate multicollinearity problems.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics. As the table shows, 13 % of the sample reported having sexted, or texted a nude/partially nude picture of him/herself in the past year. The average score for Internet-related problem for the sample was 40.87. The average score for deviant peer association was 20.80. The average age of the sample was 15.77, with nearly equal representation of males (49 %) and females (51 %). The majority of the sample (72 %) was white, with an overall average reported GPA of 2.30.

Table 2 presents results of the logistic regression analysis. The results indicate that our assumptions that Internet-related problems and social learning theories will have a link with sexting are supported in these data. As Internet-related problems increase the likelihood of sexting increases (b = 0.01, Exp(b) = 1.02). In addition, as individuals association with deviant peers increases, the likelihood of sexting also increases (b = 0.06, Exp (b) = 1.07). Finally, with regards to our control variables, the data indicate that as GPA increases the likelihood of sexting increases (b = 0.24, Exp (b) = 1.27). However, there was no significant association found between age, race, or gender and sexting. The tolerance coefficients indicate that multicollinearity is not a problem with these data.

Discussion

The current study sought to provide contributions to the currently limited scholarly research surrounding adolescent sexting by not only examining the prevalence of sexting among the study sample, but also by drawing upon theoretical literature in an attempt to help identify correlates to sexting by youth.

Regarding the overall prevalence of sexting among adolescents, about 13 % of the study sample indicated they had sent a nude/partially nude photo of themselves via text within the past year. It should be noted again that our definition of sexting in the current study was limited only to the sending of nude/partially nude texts, and did not include instances of receiving such images, which generally produced higher proportions. This is a critical distinction however, in light of our conceptual definition of sexting as a deviant behavior. However, while our finding is somewhat higher than some of the aforementioned studies (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010; Lenhart, 2009; Mitchell et al. 2012), it is indeed lower than some of the other most recent reported figures (Dake et al., 2012; Temple et al., 2012). Also worth noting, is that our findings are somewhat consistent with recent literature in that the proportion of youth in our study reporting they have engaged in sexting falls within the range (between 7 and 27.6 %) reported by other studies utilizing geographically localized samples (Dake et al., 2012; Temple et al.,s 2012). This is again in contrast to those utilizing national samples, where reports of sexting were much lower (between 2.5 and 4 %). This seems to support the probability that there is wide variation in the overall proportions of youth sexting by geography, and further supports the need to identify correlates to such behavior.

In exploring sexting behavior as one that should at a minimum be considered problematic, if not deviant, we hypothesized that youth with higher levels of internet-related problems will be more likely to engage in sexting than those with lower reports of internet-related problems. While for the most part, the items included in our composite measure of internet-related problems are not in-fact criminal, they clearly represent undesirable or problematic behaviors. The results of our logistic regression analysis support our hypothesis, indicating a significant association—as the composite score for internet-problems increases, so does the likelihood of sexting. This is also somewhat consistent with some prior research finding that youth who engage in sexting are more likely to report higher levels of texting (Dake et al., 2012) in general, as well as the use of other means of social networking (Cox Communications, 2009).

Given that the current study conceptualizes sexting as a form of youth deviance, we utilized contributions from social learning theories to further hypothesize that youth with greater levels of association with deviant peers are more likely to engage in sexting. Utilizing a 15-item composite measure for deviant peer associations, our findings suggest that youth whose composite scores indicate higher levels of association with deviant peers were indeed significantly more likely to engage in sexting than those with lower deviant peer association scores. This is a unique and promising finding, as currently there is a significant gap in the literature with respect to identifying correlates to sexting among adolescents.

Finally, similar to previous studies, ours finds no significant association between gender and sexting. There was also no association between race and sexting in the current study, however our measure was limited in that it utilized a dichotomous measure of white/non-white. The one previous study that found a significant association between race/ethnicity and sexting (Dake et al., 2012), disaggregated findings to include associations between white, African American, and Hispanic youth and sexting. This is certainly a finding worth exploring further in future research. Of our controls, only GPA was found to be significantly associated with sexting, interestingly showing that as youths’ GPA increased, so did the likelihood of sexting.

Conclusion

Given the recent media attention to, but lack of scholarly research into adolescent sexting, the current study sought to expand upon the currently limited knowledge base in this area. While much debate still exists regarding the appropriate legal implications of sexting, we have highlighted here the number of ways in which this practice can have long term negative consequences for youth. For these reasons, the current study sought to first, add to the limited scholarly work directed towards understanding the extent of sexting among adolescents, and second, connect this behavior to other forms of youth deviance and suggest a theoretical basis for understanding correlates to sexting behavior.

Overall, our findings suggest a somewhat modest overall proportion of youth (13 %) engage in sexting, as defined by the taking and sending of nude/partial nude photos via text. However, as reviewed above, this figure tends to increase when including youth who receive such images. For this reason, it does seem that sexting among youth, while perhaps not normative, may be becoming more commonplace, despite the growing media attention to the dangers of this practice. Our findings further suggest that this may in part be due to increased exposure to various social media outlets, as youth who scored higher with regards to experiencing other internet related problems were also significantly more likely to sext than those who do not.

Perhaps more important, our study provides a foundation for the theoretical underpinnings of sexting when viewed through a delinquency lens. Our findings that youth with higher composite scores for deviant peer association are significantly more likely to sext than those who do not, support the tenets of social learning theories. Future research expanding upon this would likely result in a greater understanding of sexting, and furthermore, assist in the development of strategies to help reduce this behavior among youth. While more scholarly research is needed on this topic, the current study has provided a significant, previously lacking knowledge base concerning the possible correlates to sexting by youth.

References

Akers, R. L. (1998). Social learning and social structures: A general theory of crime and deviance. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Akers, R. L., & Lee, G. (1996). A longitudinal test of social learning theory: adolescent smoking. Journal of Drug Issues, 26, 317–343. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.utep.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1006&context=gang_lee.

Armstrong, L., Phillips, J., & Saling, L. (2000). Potential determinants of heavier internet usage. International Journal of Human Computer Studies, 53, 537–550. doi:10.1006/ijhc.2000.0400.

Barak, A. (2005). Sexual harassment on the internet. Social Science Computer Review, 23, 77–92. doi:10.1177/0894439304271540.

Barkacs, L., & Barkacs, C. (2010). Do you think I’m sexty? Minors and sexting: Teenage fad or child pornography? Journal of Legal Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 13, 23–31.

Bossler, A. M., & Burruss, G. W. (2010). The general theory of crime and computer hacking: Low self-control hackers? In T. J. Holt & B. Schell (Eds.), Corporate hacking and technology-driven crime: Social dynamics and implications (pp. 57–81). Hershey: IGI Global.

Brenner, V. (1997). Psychology of computer use: XL VII. Parameters of internet use, abuse and addiction: the first 90 days of the internet usage survey. Psychological Reports, 80, 879–882.

Cox Communications (2009). Teen online and wireless safety survey: Cyberbullying, sexting, and parental controls: Research findings. Retrieved from http://www.cox.com.takeCharge/includes/docs/2009_teen_survey_internet_and_wireless_safety.pdf.

Dake, J. A., Price, J. H., & Maziarz, L. (2012). Prevalence and correlates of sexting behavior in adolescents. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 7, 1–15. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2012.650959.

Dilberto, G., & Mattey, E. (2009). Sexting: Justo how much of a danger is it and what can school nurses do about it? NASN School Nurse, 24, 262–267.

Egger, O., Rauterberg, M. (1996). Internet behavior and addiction. Retrieved from: http://www.ifap.bepr.ethz.ch/~egger/ibq/.

Freund, R., & Wilson, W. (1998). Regression analysis: Statistical modeling of a response variable. San Diego: Academic.

Goldberg, I. (1996). Internet addiction disorder. Retrieved from: http//www.cog.brown.edu/brochures/people/duchon/humor/internet.addiction.html.

Griffiths, M. D. (1998). Psychology of computer use: XLIII. Some comments on ‘addictive use of the internet’ by young. Psychological Reports, 80, 81–82.

Higgins, G. E. (2005). Can low self-control help with the understanding of the software piracy problem? Deviant Behavior, 26, 1–24.

Higgins, G. E., & Makin, D. A. (2004). Does social learning theory condition the effects of low self-control on college students’ software piracy? Journal of Economic Crime Management, 2, 1–22.

Higgins, G. E., Fell, B. D., & Wilson, A. L. (2006). Digital piracy: assessing the contributions of an integrated self-control theory and social learning theory using structural equation modeling. Criminal Justice Studies, 19, 3–22.

Hinduja, S., & Patchin, J.W. (2010). Sexting: a brief guide for educators and parents [online]. Cyberbullying Research Center. Retrieved from: http://www.cyberbullying.us.

Holt, T. J., Bossler, A. M., & May, D. C. (2010). Low self-control, deviant peer associations, and juvenile cyberdeviance. American Journal of Criminal Justice Youth & Society, 44(4), 500–523. doi:10.1007/s12103-011-9117-3.

Judge, A. M. (2012). “Sexting” among U.S. Adolescents: psychological and legal perspectives. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 20, 86–96. doi:10.3109/10673229.2012.677360.

Klettke, B., Hallford, D. J., & Mellor, D. J. (2014). Sexting prevalence and correlates: a systematic literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 34, 44–53.

Lee, G., Akers, R. L., & Borg, M. J. (2004). Social learning and structural factors in adolescent substance use. Western Criminology Review, 5, 17–34.

Lee, M., Crofts, T., Salter, M., Milivojevic, S., & McGovern, A. (2013). ‘Let’s Get Sexting’: Risk, Power, Sex and criminalisation in the moral domain. International Journal for Crime and Justice, 2, 35–49.

Lenhart, A. (2009). Teens and sexting: how and why minor teens are sending sexually suggestive nude or nearly nude images via text messaging. Washington: Pew Internet & American Life Project.

Lewis-Beck, M. (1979). Maintaining economic competition: the causes and consequences of antitrust. Journal of Politics, 41, 169–191.

Ling, R., & Yttri, B. (2005). Control, emancipation, and status: The mobile telephone in teen’s parental and peer group control relationships. In R. Kraut, M. Brynin, & S. Kiesler (Eds.), New information technologies at home: The domestic impact of computing and telecommunications (pp. 219–235). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marcum, C. D., Higgins, G. E., Freiburger, T. L., & Ricketts, M. L. (2013). Exploration of the cyberbullying victim/offender overlap by sex. American Journal of Criminal Justice. doi:10.1007/s12103-013-9217-3.

Mitchell, K. J., Finkelhor, D., Jones, L. M., & Wolak, J. (2012). Prevalence and characteristics of youth sexting: a national study. Pediatrics, 129, 13–20. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1730.

MTV and Associated Press (2009). Digital Abuse Study: MTV Networks. Retrieved from: http://www.athinline.org.

National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy and CosmoGirl.com. (2008). Sex and tech: Results from a survey of teens and young adults. Washington: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy.

Ostrager, B. (2010). SMS. OMG! TTYL: translating the law to accommodate today’s teens and the evolution from texting to sexting. Family Court Review, 48(4), 712–726. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1617.2010.01345.

Peskin, M. F., Markham, C. M., Addy, R. C., Shegog, R., Thiel, M., & Tortolero, S. R. (2013). Prevalence and patterns of sexting among ethnic minority urban high school students. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 16, 454–459.

Reyns, B. W., Burek, M. W., Henson, B., & Fisher, B. S. (2011). The unintended consequences of digital technology: exploring the relationship between sexting and cybervictimization. Journal of Crime and Justice. doi:10.1080/0735648X.2011.641816.

Shafron-Perez, S. (2009). Average teenager or sex offender? Solutions to the legal dilemma caused by sexting. The John Marshall Journal of Computer & Information Law, 26, 431–451.

Shotton, M. A. (1991). The costs and benefits of “computer addiction”. Behaviour Information and Technology, 10, 219–230.

Smith, P. K., Mahdavi, J., Carvalho, M., Fisher, S., Russell, S., & Tippett, N. (2008). Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact on secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 376–385.

Strassberg, D. S., McKinnon, R. K., Sustaita, M. A., & Rullo, J. (2013). Sexting by high school students: an exploratory and descriptive study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 15–21.

Sutherland, E. (1939). Principles of criminology. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Temple, J. R., Paul, J. A., van den Berg, P., Le, V., McElhany, A., & Temple, B. W. (2012). Teen sexting and its association with sexual behaviors. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 166(9), 828–833.

Wastler, S. (2010). The harm in ‘sexting’?: Analyzing the constitutionality of child pornography statutes that prohibit the voluntary production, possession, and dissemination of sexually explicit images by teenagers. Harvard Journal of Law and Gender, 33, 687–702.

Wolak, J., Finkelhor, D., & Mitchell, K. J. (2012). How often are teens arrested for sexting? Data from a national sample of police cases. Pediatrics, 129, 4–12.

Wolfe, S. E., & Higgins, G. E. (2009). Explaining deviant peer associations: an examination of low self-control, ethical predispositions, definitions, and digital piracy. Western Criminology Review, 10, 43–55.

Young, K.S. (1997). Internet Addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. Retrieved from: http//:www.pitt.edu/~ksy/apa/html.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ricketts, M.L., Maloney, C., Marcum, C.D. et al. The Effect of Internet Related Problems on the Sexting Behaviors of Juveniles. Am J Crim Just 40, 270–284 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-014-9247-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-014-9247-5