Abstract

Background and aims

Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) plus beta blocker is the mainstay treatment after index bleed to prevent rebleed. Primary objective of this study was to compare EVL plus propranolol versus EVL plus carvedilol on reduction of HVPG after 1 month of therapy.

Methods

Patients of cirrhosis presenting with index esophageal variceal bleed received standard treatment (Somatostatin therapy f/b EVL) following which HVPG was measured and patients were randomized to propranolol or carvedilol group if HVPG was >12 mmHg. Standard endotherapy protocol was continued in both groups. HVPG was again measured at 1 month of treatment.

Results

Out of 129 patients of index esophageal variceal bleed, 59 patients were eligible and randomized into carvedilol (n = 30) and propranolol (n = 29). At 1 month of treatment, decrease in heart rate, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and HVPG was significant within each group (p = 0.001). Percentage decrease in MAP was significantly more in carvedilol group as compared to propranolol group (p = 0.04). Number of HVPG responders (HVPG decrease >20 % or below 12 mmHg) was significantly more in carvedilol group (22/29) as compared to propranolol group (14/28), p = 0.04.

Conclusion

Carvedilol is more effective in reducing portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis with esophageal bleed. Though a larger study is required to substantiate this, the results in this study are promising for carvedilol. Clinical trials online government registry (CTRI/2013/10/004119).

Trial registration number CTRI/2013/10/004119

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastroesophageal varices are present in ~50 % of patients with cirrhosis, with a rate dependent on the severity of liver disease (42 % of patients who are Child A vs. 72 % in Child B/C) [1]. Varices develop at a rate of 7–8 % per year and the transition from small to large varices occurs at the same rate, more commonly among patients with Child B/C cirrhosis [2]. Variceal hemorrhage occurs at a rate of 5–15 % per year depending on the presence of risk factors, with variceal size, red wale marks on varices, and advanced liver disease (Child B or C) identifying patients at a high risk of variceal hemorrhage [3]. Six-week mortality with each episode of variceal hemorrhage is still around 15–25 % and also depends on the severity of the liver disease [4]. Late rebleeding occurs in ~60–70 % of untreated patients, usually within 1–2 years of the initial hemorrhage [5].

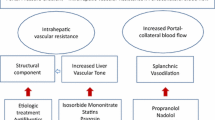

Thus, treatment/prevention of portal hypertension related bleeding with endoscopic methods and beta-blockers is the mainstay at present. The goal is to prevent the first episode of bleeding and, if the first episode of bleeding has occurred, to prevent any subsequent bleeding because each episode of bleeding is associated with significant mortality and healthcare costs. A systematic review concluded that there was limited evidence suggesting that carvedilol is more effective than propranolol for improving the hemodynamic response in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension. Long-term randomized controlled trials were required to confirm this information [6].

Carvedilol is a racemic mixture that has potent non-selective beta receptor and weak alpha receptor blocking activity. It is 2–4 times more potent than propanolol as a beta receptor blocking drug. It has two enantiomeric forms R and S. The S enantiomer is mainly responsible for the beta blocking effect of carvedilol whereas both forms contribute to alpha 1 blockade [19]. It is rapidly absorbed orally with absolute bioavailability of around 25 %. It has a rapid onset of action of 1–2 h and an elimination half-life of 6–10 h. Excretion is mainly biliary and does not require dose adjustment in renal failure [7].

Carvedilol has a greater portal hypotensive effect than propranolol in patients with cirrhosis, suggesting a greater therapeutic potential. There have been promising results with carvedilol [8], but there is lack of randomized trials comparing carvedilol and propranolol for secondary prophylaxis in variceal bleed.

The objective of the present study was to compare the efficacy of endoscopic variceal band ligation (EVL) plus propranolol and EVL plus carvedilol in the reduction of HVPG at 1 month in patients who presented with index variceal bleeding.

Methods

Study design

In this single centre, open-label randomized trial, patients were recruited prospectively from 1 June to 31 December 2013. All the patients presenting during the study period were screened for inclusion criteria. Randomization was done via computer-generated random numbers. Random numbers were placed inside opaque white serially labeled envelopes and opened after the first successful HVPG measurement.

The primary objective of the study was to compare the reduction in HVPG in both groups at 4 weeks in patients of cirrhosis with index esophageal variceal bleed.

Study participants

Patients of cirrhosis presenting with index variceal bleed in the emergency department were screened for inclusion criteria: age 18–70 years, willing to undergo hepatic venous pressure gradient measurements as per the protocol and willing to give informed consent for participation in the study. Patients were excluded for the following conditions:

-

1.

Refusal to provide consent to participate in the study.

-

2.

Previous medical, surgical or endoscopic treatment for portal hypertension.

-

3.

Neoplastic disease of any site.

-

4.

Splenic or portal vein thrombosis.

-

5.

Pregnancy.

-

6.

Contraindication to beta-blockers (atrioventricular block, sinus bradycardia with heart rate <50 beats per minute, arterial hypotension with systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, heart failure, asthma, peripheral arterial disease, or diabetes needing insulin treatment).

-

7.

Renal failure.

-

8.

Bleeding source other than esophageal varix.

Methodology

Definitions and method of measuring HVPG are given in the supplementary material.

Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleed

Those who had variceal bleed were managed with Inj Somatostatin Infusion at a rate of 250–500 mcg/h for 3 days, and Inj Cefotaxime 2 g given thrice daily after sensitivity testing. They were also given intravenous fluids and blood products including packed RBC, fresh frozen plasma and platelet-rich plasma as indicated.

Those who were detected to have active bleed were considered for urgent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (within 6 h of presentation) and variceal ligation. Those who were not actively bleeding were given endotherapy within 24 h of presentation. After days 3–5, hepatic venous pressure gradient was measured and randomization to the carvedilol (initial dose 3.125 mg twice daily) or the propranolol group (initial dose 40 mg once daily) was made. No stratification of the study population for underlying etiology of cirrhosis was done. Patients detected to have cirrhosis because of hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction were not included.

Patients who were found to be eligible for study inclusion were offered hepatic vein pressure gradient measurement and were randomized only after the first measurement was successful and above 12 mmHg.

Monitoring

Patients were reviewed in the outpatient department and the dose of propranolol was increased in increments of 20–40 mg every third day to achieve the target heart rate between 55 and 60 per min or intolerance or the maximum dose of 320 mg daily whichever was earlier. Those in the carvedilol group had their dose increased in increments of 3.125 mg every third day to achieve the target heart rate of 55–60 per min or intolerance or a total daily dose of 25 mg which ever happened earlier. HVPG was measured at 4–6 weeks after the initial measurement to quantify the change. During the study period and thereafter patients were continued on the endotherapy schedule at 3- to 4-week intervals until eradication of the varices.

Data record and statistical analysis

The data were documented in predesigned proformas. Data analysis was done using Stata software v.11.2 (Statcorp, USA).

For continuous variables, the two-sample t test with equal variance was used. If the standard deviation for these variables was high, the two-sample Wilcoxon rank sum (Mann–Whitney) test was applied to adjust the variance. For values before and after treatment, the paired t test was used. For categorical variables data, Fisher’s exact test was applied. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, a total of 129 patients presented with index variceal bleed. The CONSORT diagram of patients is shown in Fig. 1

There was no difference in demographic variables and baseline characteristics of patients in the two groups (Table 1).

Effects on hemodynamic parameters

Mean arterial pressure (MAP), radial pulse rate and HVPG between the two study groups were not statistically different at baseline. At 1 month, there was also no significant difference between two study groups (Table 2).

The median dose of carvedilol to achieve a heart rate of 55–60/min was 6.25 mg/day (6.25–12.5 mg) and that of propranolol was 40 mg/day (40–80 mg).

If the results were calculated as percentage change, it was observed that MAP decreased to a greater degree in the carvedilol group and was statistically significant.

If the change in HVPG was stratified as HVPG responder versus non-responder (defined as a reduction in HVPG ≥20 % from baseline or an absolute decrease below 12 mmHg), it was observed that the HVPG responders were significantly more in the carvedilol group (Table 3).

Adverse events

Both drugs had a similar adverse effects profile. There was no serious adverse event in either group. Tolerance of medicines and discontinuation of study medications were not statistically different between the two groups (Table 4).

There were two patients in the carvedilol group requiring drug withdrawal or a decrease in the dose. One patient with breathing difficulties required withdrawal and one patient with postural hypotension required a decrease in the dose. In the propranolol group, one patient required a decrease in the dose for breathing difficulties and two required a decrease in the dose for postural hypotension. There was one episode of rebleed in each group, occurring on day 7 in the carvedilol group and day 9 in the propranolol group.

Discussion

In patients with cirrhosis having variceal bleed, the combination of beta-blockers and band ligation is the preferred therapy as it results in lower rebleeding compared to either therapy alone. Hemodynamic studies indirectly measure the degree of portal hypertension in cirrhotic patients. Significant portal hypertension is defined as a hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) of greater than 10 mmHg [9]. It has been estimated that every increase of 1 mmHg in HVPG increases the risk of decompensation by 11 % [10].

Primary prophylaxis involves the prevention of bleed in patients with high risk varices. Several randomized controlled trials and meta analysis comparing the efficacy of beta-blockers to endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) have shown a small but significant lower incidence of first variceal bleed but no survival advantage in the EVL group. Non-selective beta-blockers demonstrated superiority to placebo in preventing the first bleed [11–15]. For secondary prophylaxis, to prevent rebleed, the combination of EVL and non-selective beta-blockers is more effective than either of them alone.

In our study, we have shown that, when used for secondary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding combined with endoscopic variceal ligation, carvedilol and propranolol both cause significant decreases in heart rate, mean arterial pressure and hepatic vein pressure gradient. The percentage change caused in mean arterial pressure is significantly more with carvedilol. This is similar to the previous study by Lin in which, on acute administration, carvedilol was more effective than propranolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate in the reduction of HVPG [16]. Carvedilol administration causes an increase in hepatic blood flow, but its systemic effects are similar to those of propranolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate. Our study has also shown similar hemodynamic effects between the two groups.

In our study, we have documented the HVPG response for the percentage decrease in HVPG in both arms. Similar results were reported by a long-term effect study of carvedilol and propranolol on HVPG in 38 patients. It was a blinded RCT between carvedilol (n = 21) and propranolol (n = 17). HVPG measurements were repeated after 90 days of treatment. HVPG decreased by 19.3 ± 16.1 % (p < 0.01) and by 12.5 ± 16.7 % (p < 0.01) in the carvedilol and propranolol groups, respectively, with no significant difference between treatment regimens (p = 0.21) [17]. In our study, the decrease in HVPG was similar but more robust and statistically significant (p < 0.001) for both groups with no difference between the groups (p < 0.11).

HVPG response in both groups with a more robust decrease in HVPG in the carvedilol group has been noted and is in agreement with previous studies [14, 18, 19]. When patients are stratified, in the present study 75 % patients are HVPG responders for carvedilol which is similar to the 64 % of a study by Benares et al, but surprisingly propranolol caused a response in 50 % patients which is very much above the 14 % response shown in the previous study [16]. The patient population of the two studies appears similar except that our study has evaluated patients after their esophageal bleeding. In contrast to the above study in which measurements were made after 1 or 2 h, in the current study measurements were done after 4 weeks.

Lo et al. showed that carvedilol was as effective as nadolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate in the prevention of gastroesophageal variceal rebleeding with fewer severe adverse events and similar survival [20]. In this study, patients were randomized to carvedilol (n = 61) and nadalol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate (n = 60). Patients were followed up for a median period of 30 months. There was no difference in rebleeding rate (51 vs. 26 %, p = 0.46), but patients on carvedilol had fewer severe adverse events, which occurred in 1 patient in the carvedilol group and 17 patients in the nadolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate (p < 0.0001).

In our study, the number of HVPG responders (HVPG decrease >20 % or below 12 mmHg) was significantly more in the carvedilol group (22/29) as compared to the propranolol group (14/28; p = 0.04). Though we do not have long-term follow-up of the patients for rebleeding to compare, we are hopeful that the HVPG response will get translated into meaningful clinical outcomes of decreased rebleeding. There was only one rebleed in each group at 1 month. Adverse events in both groups were not significant (p < 0.05) and only three patients in the carvedilol group and two patients in the propranolol group required dose reduction. Attrition was one patient in the first month in each group.

The study has obvious shortcomings. Firstly, though it is a randomized trial, it is not double-blinded. So, a double-blinded study in the future with similar patient profiles can give strength to the available evidence. Secondly, this trial has assessed the hemodynamic response only by the decrease in HVPG. How much of the HVPG response actually gets translated into a decreased incidence of rebleeding and also a decrease in the risk of decompensation needs to be seen in longer follow-up studies.

Conclusion

On the basis of this study, we can state that, in patients with variceal bleed due to portal hypertension related to cirrhosis, carvedilol with endoscopic variceal ligation for prevention of rebleeding is an effective treatment. It leads to a statistically higher number of patients on carvedilol having an adequate response as compared to propranolol.

Abbreviations

- AIH:

-

Autoimmune hepatitis

- EHPVO:

-

Extrahepatic portal venous obstruction

- EVL:

-

Endoscopic variceal ligation

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HVOTO:

-

Hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction

- HVPG:

-

Hepatic venous pressure gradient

- LFTU:

-

Left to follow-up

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial blood pressure

- NASH:

-

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- TIPS:

-

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

References

Kovalak M, Lake J, Mattek N, Eisen G, Lieberman D, Zaman A. Endoscopic screening for varices in cirrhotic patients: data from a national endoscopic database. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:82–88

Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, Rinaldi V, De Santis A, Merkel C, et al. Incidence and natural history of small esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol 2003;38:266–272

North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med 1988;319:983–989

Abraldes JG, Villanueva C, Bañares R, Aracil C, Catalina MV, Garci A-Pagán JC, et al. Spanish Cooperative Group for Portal Hypertension and Variceal Bleeding. Hepatic venous pressure gradient and prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy. J Hepatol 2008;48:229–236

Augustin S, Muntaner L, Altamirano JT, González A, Saperas E, Dot J, et al. Predicting early mortality after acute variceal hemorrhage based on classification and regression tree analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;7:1347–1354

Aguilar-Olivos N, Motola-Kuba M, Candia R, Arrese M, Méndez-Sánchez N, Uribe M, et al. Hemodynamic effect of carvedilol vs. propranolol in cirrhotic patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Hepatol 2014;13:420–428

Ruffolo RR Jr, Gellai M, Hieble JP, Willette RN, Nichols AJ. The pharmacology of carvedilol. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1990;38:82–88

Stanley AJ, Dickson S, Hayes PC, Forrest EH, Mills PR, Tripathi D, et al. Multicentre randomized controlled study comparing carvedilol with variceal band ligation in the prevention of variceal rebleeding. J Hepatol 2014;61:1014–1019

Feu F, García-Pagán JC, Bosch J, Luca A, Terés J, Escorsell A, et al. Relation between portal pressure response to pharmacotherapy and risk of recurrent variceal haemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Lancet 1995;346:1056–1059

Ripoll C, Groszmann R, Garcia-Tsao G, Grace N, Burroughs A, Planas R, et al. Portal Hypertension Collaborative Group. Hepatic venous pressure gradient predicts clinical decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2007;133:481–488

Pagliaro L, D’Amico G, Sörensen TI, Lebrec D, Burroughs AK, Morabito A, et al. Prevention of first bleeding in cirrhosis. A meta-analysis of randomized trials of nonsurgical treatment. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:59–70

Imperiale TF, Chalasani N. A meta-analysis of endoscopic variceal ligation for primary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding. Hepatology 2001;33:802–807

Khuroo MS, Khuroo NS, Farahat KL, Khuroo YS, Sofi AA, Dahab ST. Meta-analysis: endoscopic variceal ligation for primary prophylaxis of oesophageal variceal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005;21:347–361

Tripathi D, Graham C, Hayes PC. Variceal band ligation versus beta-blockers for primary prevention of variceal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;19:835–845

Gluud LL, Klingenberg S, Nikolova D, Gluud C. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers as primary prophylaxis in esophageal varices: systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:2842–2848

Lin HC, Yang YY, Hou MC, Huang YT, Lee FY, Lee SD. Acute administration of carvedilol is more effective than propranolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate in the reduction of portal pressure in patients with viral cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1953–1958

Hobolth L, Møller S, Grønbæk H, Roelsgaard K, Bendtsen F, Feldager Hansen E. Carvedilol or propranolol in portal hypertension? A randomized comparison. Scand J Gastroenterol 2012;47:467–474

Samanta T, Purkait R, Sarkar M, Misra A, Ganguly S. Effectiveness of beta blockers in primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in children with portal hypertension. Trop Gastroenterol 2011;32:299–303

Bañares R, Moitinho E, Piqueras B, Casado M, García-Pagán JC, de Diego A, et al. Carvedilol, a new nonselective beta-blocker with intrinsic anti- Alpha1-adrenergic activity, has a greater portal hypotensive effect than propranolol in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 1999;30:79–83

Lo GH, Chen WC, Wang HM, Yu HC. Randomized, controlled trial of carvedilol versus nadolol plus isosorbide mononitrate for the prevention of variceal rebleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;27:1681–1687

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical clearance

Institute ethics subcommittee, AIIMS, gave clearance to the study, vide ref No IESC/T- 120/01.03.2013,RT-09/03.05.2013 and RT-36/15.06.2013. Patients or their legal representatives provided written informed consent. The protocol was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee and registered with the clinical trials online government registry (CTRI/2013/10/004119).

Conflict of interest

Vipin Gupta, Ramakant Rawat, Shalimar, Anoop Saraya declare no conflict of interest; no financial support was received for the study

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, V., Rawat, R., Shalimar et al. Carvedilol versus propranolol effect on hepatic venous pressure gradient at 1 month in patients with index variceal bleed: RCT. Hepatol Int 11, 181–187 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-016-9765-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-016-9765-y