Abstract

“Fire regime” has become, in recent decades, a key concept in many scientific domains. In spite of its wide spread use, the concept still lacks a clear and wide established definition. Many believe that it was first discussed in a famous report on national park management in the United States, and that it may be simply defined as a selection of a few measurable parameters that summarize the fire occurrence patterns in an area. This view has been uncritically perpetuated in the scientific community in the last decades. In this paper we attempt a historical reconstruction of the origin, the evolution and the current meaning of “fire regime” as a concept. Its roots go back to the 19th century in France and to the first half of the 20th century in French African colonies. The “fire regime” concept took time to evolve and pass from French into English usage and thus to the whole scientific community. This coincided with a paradigm shift in the early 1960s in the United States, where a favourable cultural, social and scientific climate led to the natural role of fires as a major disturbance in ecosystem dynamics becoming fully acknowledged. Today the concept of “fire regime” refers to a collection of several fire-related parameters that may be organized, assembled and used in different ways according to the needs of the users. A structure for the most relevant categories of parameters is proposed, aiming to contribute to a unified concept of “fire regime” that can reconcile the physical nature of fire with the socio-ecological context within which it occurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The burning of biomass may, like windthrow and avalanches, be considered a major disturbance and evolutionary force affecting vegetation structure and generating disturbance-adapted ecosystems (Pyne et al. 1996; Caldararo 2002). The prominent ecological role of fire has been investigated in many studies (e.g. Swetnam 1993; Bond and van Wilgen 1996; Bengtsson et al. 2000; Brown and Smith 2000; Bradstock et al. 2002; Bergeron et al. 2002; Turner et al. 2003). In this context, “fire regime” and related concepts such as “historical fire regime”, “shift in fire regime”, “natural variability of fire regimes” and “natural fire regime” are now of common use in modern fire ecology and fire management.

This paper reconstructs the origin of these concepts, reviews the current understanding of “fire regime” and suggests an updated definition.

The French origins

The term “regime” originates from Latin regere (to direct, to manage, to conduct, or to rule) and was very likely introduced into English from French «régime»,Footnote 1 as the spelling “régime”, was frequently used in older English texts (e.g. Raulin 1904; von Herrmann 1910; Henry 1919, 1923; Reed 1926).

In French the concept of regime was usually used to describe variations in characteristics regularly occurring in time and space, which is typical of meteorological and climatic variables, such as rainfall and temperature, with their periodic cycles (e.g. seasons). In the technical and scientific French literature, the use of the term «régime» is documented since the 19th century: «Mémoire relatif aux travaux exécutés pour améliorer le régime des eaux sur la rivière et le canal de l’Ourcq et pour rendre ces cours d’eau navigables» (Vuigner 1862); «Notice sur le régime de la pluie sous le Bassin de la Seine» (Belgrand 1865); «Rhône inférieur; de l’endiguement des cours d’eau, de son utilité pour la conservation des intérêts agricoles, de l’influence qu’il exerce sur le régime des eaux et sur le fond des fleuves» (Delorme 1866); «La Seine. Etude hydrologique. Régime de la pluie, des sources, des eaux courantes» (Belgrand 1872).

Related expressions can be found in the American literature in the early 20th century, e.g. “seasonal rainfall régime” (Raulin 1904), “river régime” (von Herrmann 1910), “rainfall régime” (Henry 1919), “temperature régime” (Henry 1923) and “pressure régime” (Reed 1926).

It thus seems very likely that the term “regime” passed into English usage from the French. The use of the term «régime» related to fire in the French literature in the 19th century was rare, but we found the expression «régime dangereux des incendies» (literally “dangerous regime of fires”) among the arguments gave in favour of a bill of 1857 April 28, aimed to ban the shepherd’s use to regularly burn the Gascony wetlands to improve the pasture (Duvergier 1857, pp. 151–153; Heurtier and Denjoy 1857; Cuzacq 1877, p. 25; Depelchin 1887, p. 380). Similar expressions can be found at the beginning of the 20th century in texts referring to the problem of “pastoral burning”Footnote 2 in the Pyrenees (Buffault and Fabre 1904, p. 610; Fabre 1904, p. 545; 1905; Picard 1921, pp. 58–59; Puyo 1999, p. 627).

By far the majority of the early mentions of “fire regime” in the French literature concern the African colonies. For instance already in the first half of the 19th century, the baron Jacques-François Roger (1787–1849) used the expression «régime des incendies» to describe the pastoral burning practices in Senegal (Roger 1828). Long after, the commandant Georges-Joseph Toutée (1855–1927) mentioned the same expression in his colourful account of an exploratory expedition in Nigeria and Benin, using it to indicate the high incidence of fires caused by natives with the intent to facilitate the hunting and agricultural activities (Toutée 1899, pp. 18, 74, 80). The alternative expression «régime des feux» (literally “regime of fires”) was used later, from about the early 1910s, in many scientific publications about vegetation in the French colonial territories in Africa. Particularly striking is repeated use of this expression (17 times, a record-breaking number for those days) by the French botanist Perrier Henri de la Bâthie (1873–1958) in his two treatises on the vegetation of Madagascar (de la Bâthie 1912 and 1921).Footnote 3 De la Bâthie’s work stimulated a series of similar investigations in which the term «régime des feux» was allowed, including a number of French authors involved in the studying forest and forestry in African colonies (e.g. Carle 1920; Dandouau 1922; Chevalier 1927; Erhart 1929, 1935; Anthony 1932; Aubréville 1937, 1938). Among them was the French botanist Jean Henri Humbert (1887–1967), an early fire specialist in Africa, who frequently used this expression in many of his writings (Humbert 1927, 1931, 1933, 1936, 1940, 1947, 1949, 1953, 1960). De la Bâthie’s terminology was also adopted by some Belgian researchers working in the Belgian Congo, Belgium’s main colony (Lebrun 1936; Offermann 1953).

Shortly after the Second World War, we find «régime des feux» mentioned again in the scientific literature on vegetation and soils in Africa (Schnell 1949, 1950, 1952, 1957, 1961; Moureaux 1950; Delcourt 1952; Pitot 1953; Riquier et al. 1952; Moureaux and Tercinier 1956; Aubréville 1953, 1957). Most of them refer to the vegetation in Madagascar, the “Isle of fire” according to Kull (2004), or to French or Belgium colonies in Africa. In contrast, there are few examples of the use of this expression in relation to Europe (Kuhnholtz-Lordat 1938; Kuhnholtz-Lordat and Heim 1958) or North America (Erhart 1935).

In conclusion, it seems that the concept of “fire regime” originated principally in the 1920s among a united circle of Francophone botanists, pedologists, agronomists and foresters mainly working in the African colonies.

Behind the original concept of fire regime

De la Bâthie (1921) and Humbert (1927) considered recurrent fires and the related «régime des feux» as an anthropogenic imposition on the ecosystem, and a destructive and regressive process opposed to the natural order. In de la Bâthie and Humbert’s original usage fire regime was a synonym for the dictatorship of fire over the ecosystem, i.e. a condition of excessively frequent fire, nearly a reign of fire and fire domination, where fire imposes a severe and selective regime on the ecosystem. Fire regime was mostly associated with terms such as «soumis» (=subdued, subjugated), «instauration» (=establishment) or «echapper» (=to escape), emphasizing the sense of submission to fire. The following years Humbert partly deviated from the original usage, sometimes coming closer to the present meaning. For example, he refers to the “worsening of the fire regime” (Humbert 1933, p. 838), reporting that the fire regime is widespread across all the Africa, but “with different frequencies and intensities” (Humbert 1931, p. 209). He also describes the “preventive burning regime” used in Drakensberg National Park (South Africa) as a strategy to protect tourists against rapid fire propagation (Humbert 1936, p. 94).

Generally speaking, however, early usage of fire regime had clearly a more restricted application and a more negative meaning than it does today. This was in tune with the need to preserve the agricultural and silvicultural resources in the colonial territories. The concept was developed by colonial scientists preoccupied with the assumed process of savannization, soil degradation, desiccation and desertification affecting wide areas of Africa and others subtropical regions (Fairhead and Leach 1996). They were convinced that the African grass-dominated savannas were essentially a fire sub-climax that had evolved from primeval forest as a result of repeated burning.

De la Bâthie, Humbert, Aubréville, Schnell, Chevalier and others belonged to a group of scholars who were easily able to start a fashion among the international community of tropical scientists and who were thus quite influential. For example their works were known also by Italian and Spanish scholars, who translated fire regime respectively by “regime dei fuochi” (Roselli-Cecconi 1920, p. 441) and “régimen de fuegos” (Cola Alberich 1953, pp. 50, 52). This was possible partly due to a certain alarmism widespread in the colonial administrations. From a scientific point of view, their assumptions were supported by the Clementsian successional theory that placed fire in an unfavourable light as a factor external to ecosystems, which hinders or ever ruins natural evolutionary processes. According to Clements (1916), ecosystem dynamics represent a complex but well-defined sequence of stages (successions) towards a self-perpetuating equilibrium between vegetation and a site (climax). Such a succession is characterized by a sequential establishment of different plant communities driven by dynamic interactions between soil and vegetation, evolving from lower to higher forms until a state of equilibrium is reached. The derived climax formations are organic entities able to (re)create themselves, repeating the stages of their development. According to this theory, disturbances such as fire are considered regressive and destructive, maintaining the community in a sub-climax stage. When such inhibiting forces are removed, normal development can slowly resume and progress to the proper climax (Clements 1916).

In the United States, ideas about the universality of change in nature existed prior to Clements (Warming 1895; Cowles 1901), but were long ignored in the dominant theories (Cooper 1926). An opportunity to debate Clements climax view arose in 1926, when Henry Allan Gleason expressed his dissenting voice in an article on the “the individualistic concept of the plant association”. Gleason (1926, p. 16) criticized the supposed analogy between climax communities and organisms, claiming that plant associations are more likely to be due to coincidence than to predefined developmental phases in a climax organism. But Gleason’s provocative ideas were mostly not even discussed among ecologists, who tended not to question Clements theory. Clements theory represented, in fact, the cultural main trend, fitting in well with the dominant aesthetic tastes of the first part of the 20th century with its need for order, progress, control and organization. In this context the theory of climax and succession was probably perceived as profitable, comforting and reassuring, which could explain why it remained uncontested for so long.

In Australia, on contrary, the awareness on the existing interplay between fire and vegetation as well as on the positive effect of using fire for removing grassy fuel and improving the pasture land is already recorded since the middle of the 19th century (Gill et al. 2002; Noble and Grice 2002). Despite such awareness and the notable scientific work on fire ecology in the first half of the 20th century (Gill et al. 2002), there is no trace of a widespread use of the fire regime concept before the 1960s.

In Europe, the ecological role of fire has been less a subject of discussion, since most forests are not primary, but have been shaped by long-term exploitation (Bengtsson et al. 2000). In Europe humans have used fire for hunting and to improve pastures at least since Neolithic times (Goldammer et al. 1997). Where ploughing was not possible, fire was used to improve the agricultural potential of the land (called Brandwirtschaft by Schneiter 1970). With industrialization, the agricultural revolution and the availability of chemical fertilizers fires were used much less often to clear agricultural areas. At the same time, the economic value of the forests rose, and their importance for the environment became increasingly recognized. Fire was generally seen as an agent of degradation (Pyne 1997). In the 19th century, many European countries introduced legislation to restrict or even prohibit the burning of lands. The traditional practice of pastoral fires continued in some areas (Schneiter 1970; Conedera et al. 2007), as did some isolated cases of controlled fire activities such as the «petits feux» system in the French Maures and Esterel regions. Apart from these few exceptions, fire suppression became the dominant management strategy throughout Europe (Pyne 1997).

This approach to management was exported by the emigrants from the “Old World” to America (Leiberg 1899; Pack 1922; Pyne 1997). Clements’ theory became the prevailing paradigm among ecologists and provided the cultural background for industrial forestry, where fires were considered the most severe economic threat to forest resources. In “The School Book of Forestry”, Pack (1922) stated that fire is “the greatest enemy of the forest” destroying “millions of dollars worth of timber every year”.

From French to English

In the earliest English texts dealing with fire, most authors do not refer to a “fire regime” but use alternative (and often incomplete) expressions such as “fire chronology” (Boyce 1921, cited in Wagener 1961, p. 739), “average area per fire by seasons” (Larsen and Delevan 1922, p. 55), “fire damage” (Lachmund 1923, p. 725), “average fire frequency” (Show and Kotok 1924, p. 2), “fire interval” (Gates 1930, pp. 255–256), “average fire interval” (Humphrey 1953, p. 163; Cooper 1960, p. 137), “fire frequency” (Weaver 1959, p. 16), “fire intensity” (Byram 1959, p. 79), “incidence of fire” (Curtis 1959, p. 305), “different burning treatments” (Little and Moore 1953, p. 1; Moore 1960, p. 258) and “fire history and frequency pattern” (Wagener 1961, p. 747). In particular, the term is missing from the “Glossary of terms used in forest fire control” (Forest Service 1956) and from the voluminous works of Davis et al. (1959) and Moore (1960). Even some key personalities representative of this period do not remember any use of this term before the 1960s (Talbot, personal communication).

Furthermore, until the 1960s, alternative expressions to “fire regime” (FR) or “regime of fire” (RoF) were more often used, such as “burning regime” (BR) or “regime of burning” (RoB). BR and RoB emphasize the anthropogenic and intentional aspects of fire events, especially in discussions of fire experiments, burning treatments, and prescribed, controlled or agricultural burning.

The FR-term was occasionally used in the USA in the first decade of the 20th century (Bray 1906; Schenck 1907) and later by Buell and Cantlon (1953), but otherwise the expressions FR and BR in English were used nearly exclusively in British territories, especially in the colonies in Africa and Southern Asia (Table 1). William Bray (1865–1953) used the FR expression twice in “Distribution and adaptation of the vegetation of Texas” (1906, p. 82) and Carl Alwin Schenck (1865–1959) once in “Biltmore lectures on sylviculture” (1907, p. 162). These linguistic innovations remained, however, completely isolated. Bray and Schenck were possibly influenced by their academic experiences in Europe.Footnote 4 After these early usages the FR expression fell into oblivion for more than 40 years in the USA, at least according to our bibliographic information.

How exactly the terms were transmitted from French colonial scientists to Anglophone scientists is an open question. As two major colonial powers, France and Britain were close not only in terms of geographical proximity but also thanks to a relationship of “cordial understanding” and cooperation (Viot and Radice 2004) that stimulated, among other things, an intense exchange in the scientific domain. Common solutions to certain problems faced by the colonial and resource administrators were sought (Aubréville 1973). The spread of the terms in the African colonies (Colonial Office 1939; Dawkins 1949; Wigg 1949; Glover et al. 1955; Cooling 1959; Fanshawe 1959a, b) may have resulted directly from contact with French colonial scientists during international congresses (Humbert 1933, 1936, 1949; Offermann 1953) or in other occasions for intercultural exchange or proximity in African countries. In the South Asian colonies, especially in India (Hearle 1888; Ford-Robertson 1927; Gorrie 1936; Champion 1936; Raynor 1940; Champion and Griffith 1948; White 1957), the spread of the terminology may have arisen during the historical presence of both the French and British in eastern India (Decraene 1994; Mathew 1999). Alternatively, there could have been a transfer from French tropical botanists working in Africa to British colleagues studying Indian vegetation under tropical conditions. Last but not least it is important to consider that at least until 1885 most of British colonial foresters were trained at the prestigious «École Nationale Forestière» of Nancy (Lorraine, France) where «régime» was certainly a largely used keyword that could easily remain imprinted in the memory of British students as a captivating and multipurpose foreignism (Roach 1995, p. 292; van Oosthoek 2003). The early use of the term “régime of fires” in an article of 1888 highlighting the clash of interests between colonial forestry and the burning practices of the native shepherds in Northern India is therefore not surprising (Hearle 1888, p. 248). The author, Nathaniel Hearle, was at that time conservator of forest of the Jaunsar Division but he received his training in forestry in Nancy.Footnote 5

The turning point in the 1960s

The concept of fire regime finally began to be adopted in the United States in the early 1960s, when the idea of fire disturbance as a basic natural force shaping ecosystems started to be widely accepted and implemented in the wildlife management strategies of the national parks (Leopold et al. 1963). This was the result of a long process which marked the overcoming of the previously dominant Clementsian successional theory.

Some authors first tried to adapt climax theory to incorporate the idea of the natural role of disturbance. They claimed that an apparently stable forest community is a vast patch-work of distinct phases that are continually changing and dynamically related to one another. Such patches are created when openings are formed after the death of a group of old trees or after a natural disaster (Cooper 1926, 1961; Watt 1947; Komarek 1964). Since the 1940s, Carl Saurer developed the position that most grasslands and savannas are fire grass climax, that is climax associations caused and maintained by fire rather than by climate (Sauer 1944, 1950). The natural role of fire, the existence of fire-climax, and the positive role of frequent fires that consume surface fuels, have been discussed since the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century (among others Pinchot 1899a, b; Sudworth 1900; Muir 1901; Jepson 1909; Hoxie 1910; Harper 1911, 1913; Greswell 1926). The use of prescribed burning to prevent the accumulation of fuel on the ground was sometimes advocated (Simerly 1936; Morris and Mowat 1958; Stoddard 1969; Biswell 1989). Weaver (1952) started experiments in the early 1940s to investigate the use of prescribed burning to thin dense patches of ponderosa pine saplings and small poles and to reduce the risk of fire. In the fall of 1948, prescribed-burning tests also took place in ponderosa pine stands on the White Mountain of the Fort Apache Indian Reservation (Weaver 1952; Morris and Mowat 1958). In the late 1940s, the National Park Service of the Sequoia National Park accepted the principle that fire should not always be suppressed as quickly as possible throughout the Park. In 1951 Biswell initiated controlled burning demonstrations at several locations in California to reduce fuel load and protect areas from severe forest fires. But several decades were necessary before the validity of his approach finally became widely recognized (Biswell et al. 1973; Biswell 1989). In 1957, the first controlled burning plan within the national park system for more than 30 years was approved. This was part of several trials of prescribed burning on the Colville Indian Reservation in north-central Washington (Rothman 2005). Anti-fire critics, however, overrode these early prescribed-burning attempts, and total fire suppression prevailed for many decades (Cooper 1960; Kilgore 1976).

The relationship of humans with fire was negatively biased for a long time by ideological, emotional, political and philosophical views of fire that influenced forest and park management, often masking contrary evidence from the field and from scientific work. To overcome such a symbolic and deeply rooted pre-conception of fire as a destructive force, a more favourable culture coupled with strong ecological and economic evidence disputing this view were needed.

From an ecological and silvicultural point of view, the negative effects of fire suppression became very clear in the 1950s and 1960s when several disastrous wildfires occurred. According to Kilgore (1976), one of the turning points came with a dramatic wildfire in 1955 just west of Kings Canyon National Park that consumed more than 5,000 ha of brush and forest in a very short time and threatened the famous Grant Grove of sequoias. Stagnation in regeneration of tree species adapted to a particular fire regime also became an increasing problem for silviculturists concerned with the conservation of forest structure and species composition in stands that became overly dense and stocked in the absence of regular surface fires (Weaver 1947; Bergeron and Brisson 1990; Lageard et al. 2000; Dey and Hartman 2005). With time the systematic fire suppression approach increases the occurrence of severe wildfires, and thus fails to absolutely protect homes and communities and threatens the existence of fire-dependent forest stands. This creates a seemingly self-contradictory situation known as the fire paradox: the more efficiently fires are fought, the larger and more intense are the few fires that get out of control (Ingalsbee 2002).

The paradigm shift towards full acknowledgement of the natural role of fires as a major disturbance in ecosystem dynamics became possible in the early 1960s when the role of deterministic patterns in society as a whole was questioned, and the cultural, social and scientific situation became more favourable. This corresponded with the rise of movements for women’s rights, the promotion of multiculturalism and the conclusive decline of colonialism. Similarly, there was a shift in scientific thinking, with the publication of chaos theory (Lorenz 1963) and the acceptance of disturbance as an evolutionary driving force in nature on scales ranging from the geological (Newell 1967; Palmer 1999) to the cellular (Lockshin 1963; Clarke and Clarke 1996; Gorski and Marra 2002).

This favourable context made it also possible to separate the positive view of natural fire disturbance from the truly destructive forms of human fire-setting and arson such as the current destruction of the evergreen tropical forests by slash-and-burn activities or past anthropogenic fire disturbance of forest ecosystems (e.g. Tinner et al. 1999; Keller et al. 2002; Tinner and Ammann 2005). Against this background, the concept of a fire regime finally emerged.

A fundamental trigger for this was a brief document presented at the First World Conference on National Parks in Seattle in July 1962, which summarized some basic principles for the management of national parks (Bourlière 1964). A minor but very important detail was that the draft of this document involved 15 peoples representing eight nations, who were coordinated by the French chairman, François Bourlière (1913–1993), an expert on African and tropical ecology. He was many years the editor-in-chief of «Revue d’Ecologie» (formerly «La Terre et la Vie»), with a complete mastery of both French and English. In this document the fire regime concept appears in an innovative context, with fire considered as “an essential management tool to maintain East African open savanna or American prairie” (Bourlière 1964, p. 364). The members of the committee expressed concern about “changes in the fire regime” as they were aware that the total suppression fire may be detrimental to such ecosystems.

Lee Merriam Talbot, ecologist and geographer with long experience in East Africa and member of this committee declared that “a given pattern of fire may also be a part of a habitat web, maintaining a given habitat until its regime is altered” and that the “complete protection of an area from fire may have as disastrous an effect on the existing habitat as overburning it” (Talbot 1964, p. 297). In the following year these ideas were integrated in a major report presented by Aldo Starker Leopold (1913–1983) and four co-authors at the 28th North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference. This report clearly questioned the “regime of equally unnatural protection from lightning fires” (Leopold et al. 1963, p. 32) imposed until then in national parks, and recommended to maintain, or where necessary to recreate, as nearly as possible, the conditions that prevailed when these areas were first visited by white settlers.

Unlike with de la Bâthie and Humbert, the fire regime concept in the 1960s became primarily a system for describing, quantifying and characterizing fire occurrence, without any value connotations. A fire regime is neither negative nor positive and may refer to any fire frequency, including fire exclusion. Soon the report, better known as the Leopold Report, was viewed as a milestone in the domain of national park management, ecology and wilderness protection. It was discussed during conferences (Berry et al. 1969; Nelson and Scace 1969) and cited in many publications even in the field of forestry and fire fighting (Craig et al. 1963; Owen 1972; Vankat 1977, p. 26). In particular, the report was discussed at the second annual Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference (March 14–15th, 1963, Tallahassee) by a large team of fire specialists (Komarek 1963, pp. XI–XV). Still today many see the Leopold Report as opening up a new phase in fire ecology and fire management. Rothman (2007, p. 97) asserts that “after the Leopold Report a change in strategy became hard to resist”, Sellars (1997) describes it as a “threshold document” and Kilgore (2007, pp. 99–101) even refers to the “Leopold Report era”.

Spread of the term fire regime in recent decades

We tried to quantify the recent increase in the use of the FR and related expressions by searching for keywords in JSTOR and ScienceDirect.

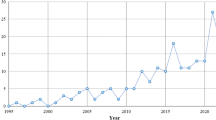

During the 1960s in the USA and in the UK, expressions related to fire regime such as “fire regime” (FR), “regime of fire” (RoF), “burning regime” (BR) and “regime of burning” (RoB) started to circulate among fire experts. Rarely used at first, these expressions experienced an almost exponential increase in use, mirroring the promotion of fire ecology and fire management in the scientific community (see Fig. 1, right y-axis, line with triangular symbols). To be precise, the exponential increase concerned nearly exclusively the FR expression, to the detriment of the other alternative expressions that were gradually less frequently used. The shift in the use of fire regime related terms and a terminological specification process coincided with the spread of the fire regime concept. In particular, the BR and RoB expressions lost their dominant position, while “fire regime” and “fire regimes” became the mostly widely used keywords, and nowadays are used exclusively (without any alternative expressions) in more than 90% of the articles mentioning FR-related expressions (Fig. 1, left y-axis, line with square dots). Furthermore, whereas “fire regime” and “fire regimes” are used almost solely in the domains of wildfire ecology and management, the BR and RoB expressions are also often used in some areas in physics, astrophysics and mathematics, which have little or nothing to do with biomass burning processes (e.g. Niemeyer and Kerstein 1997; Son and Fisch 2006). Even the expression “regime of fires”, that had an advantage over “fire regime” until the 1960s (Table 1) thanks to its direct derivation from the French «régime des feux», has nearly vanished in recent decades, appearing only in a few English publications of French authors (for instance, Carcaillet 1998). Other alternative expressions, e.g. “firing regime”, are used only in rare and specific situations such as in describing the intentional burning practices of indigenous people (Verran 2002). Another interesting alternative expression, “pyrological regime”, seems to be confined to the Russian scientific literature (Furyaev 1996; Furyaev et al. 2008; Yevdokimenko 2008).

Total number of articles (line with triangular symbols) mentioning at least one expression related to fire regime (“fire regime”, “fire regimes”, “regime of fire”, “regime of fires”, “regimes of fires”, “regimes of fire”, “burning regime”, “burning regimes”, “regime of burning”, and “regimes of burning”) and the percentage of these (line with square dots) mentioning “fire regime” or “fire regimes” exclusively. Values for 2005–2009 are estimated

A possible reason for such a terminological shift may have to do with the fact that the first basic and clear definitions of terms that appeared in the 1970s were for FR-term (Gill 1973, 1975, 1977; Heinselman 1973, 1978; Methven 1978; Sando 1978), but not for the other alternative expressions. These basic definitions simply reduced the concept of fire regime to a short list of its main components, allowing some simplification of a rather abstract and complex scientific concept. Fire regime was defined in a practical way to include a few measurable parameters indispensable for describing the recurrence patterns of fires. Although not throughout correct conceptually, such a definition of fire regime was extremely useful and user-friendly. It contributed in the following decades to the spread of FR as a keyword in the scientific literature worldwide.

To prove that the increase of FR-term presence in scientific literature amply exceed the rising trend of the total number of articles published every year and stored in the digital archives, we compared the number of papers citing the FR expression with the number of papers mentioning keywords such as “forest” and “fire” in the full text. This analysis provided a clear confirmation that the term FR is continuing to spread more quickly than the general numerical increase of scientific publications (Fig. 2). Recent articles citing FR represent roughly 2% of the articles dealing with “forests” and 10% of the articles dealing with both “forests” and “fires” (Fig. 2). Furthermore, FR is increasingly used in paper abstracts and in titlesFootnote 6 (Fig. 3), and the average number of FR occurrences per page has constantly increased since the 1980s (Fig. 4).

Percentage of articles with at least one mention of “fire regime” or “fire regimes” (FR) in the full text, in relation to the total number of articles with “forest” only (line with triangular symbols) or with “forest” and “fire” (line with square dots) in the full text. Values for 2005–2009 are estimated

In conclusion, FR seems today to be nearly an unavoidable keyword in any discussion of fire (Conedera et al. 2009). All the alternative expressions (RoF, BR and RoB) seem to have become largely obsolete. The original French expression «régime des feux» has also had little success. In fact, after a very promising beginning in the first half of the 20th century, de la Bâthie and Humbert term did not meet with any great approval, probably owing to its original usage among the advocates of fire suppression, which imposed a delay in adapting to new trends in fire ecology and fire management. In 2009 there were on average 180 websites mentioning “fire regime” per million English-speakers in the USA and only seven websites mentioning «régime des feux» per million French-speakers in France. The number of Canadian webpages citing «régime des feux» is 64 per million of French-speakers, what is closer to the USA average value for FR. This has partly to do with French-Canadian webpages being translated from English, but it seems to indicate that the circle is now closing with an inverse transmission of the FR concept from English to French in Canada.

Current definitions of fire regime

The first definitions of fire regime reflected the increasing need for fire ecologists and managers to develop a unified framework for classifying the main characteristics and dimensions of fire occurrence within a particular area or ecosystem over a certain period (Heinselman 1973; Gill 1975, 1977; Aldrich et al. 1978; Gill and Groves 1981; Christensen et al. 1981; Heinselman 1981; Tainton and Mentis 1984; Falk and Swetnam 2003). Over time, ecologists, firefighters and managers began also to consider the ecological and economic role played by fires. This led to a progressive extension of the list of parameters and of the meanings included in the definitions of fire regime (Booysen 1984; Johnson and Van Wagner 1985; Mutch 1992; Agee 1993; Whelan 1995; Pyne et al. 1996; Goldammer et al. 2001; Gill and Allan 2008). The concept of fire regime has since developed into a generalized and structured description of the role of fire in ecosystems, mostly involving the parameterization of fire occurrence in a defined space–time window (Falk and Swetnam 2003).

In the past decades, most used definitions of FR in the wildfire literature refer to a core group of parameters describing which fires occur when and where according to frequency, size, seasonality, intensity and type. In this sense, against the innumerable variables describing the history of fire events, such a strict FR definition is a selection of those that are more related to fire, more independent from other causal variables, and generally more determinant in terms of ecological or environmental effects (Gill 1975; Gill et al. 2002; Gill and Allan 2008). But in reality there is no clear boundary separating the factors strictly related to fire (e.g. duration and extension of the flames) and all the other complementary factors (e.g. ignition causes, drought severity, fuel flammability, wind conditions, smoke plume characteristics, duration of smouldering combustion, mortality of trees, fire fighting costs, damages to buildings, etc.). Furthermore, when several overlapping fires occur over time, it is difficult to retain an area where fire characteristics and effects are homogeneous and the considered area may be rather the result of the aggregation of single point fire regimes (Gill et al. 2002). In a complex process like fire, that involves temporal cascades, interactions and feedbacks, every cause is also an effect, every effect may be a causal variable, and no variable is truly independent. Any selection of the variables of the FR is therefore questionable and implies a significant degree of subjectivity.

In fact, a number of other attributes and derived variables may also be considered in more aim-oriented (ad hoc) or extended definitions of FR. Fire regime may refer to different times and time windows (past, present, or future; a single event, years, decades, centuries, or millennia); different spatial or functional units affected, e.g. a single ecosystem, a single vegetation type or a specific geographical area; and different fire origins (natural or anthropogenic). A definition of FR may consider not only pyrological characteristics (fire intensity, fire type and fire behaviour), but also the variance or predictability of these characteristics (Christensen 1993, p. 237), the conditions that affect fire occurrence (fuel type, fire weather, and so on), and the immediate impact or severity of the fire. The development of fire research has led to an extended definition of fire regime that allows a satisfactory arrangement even for complex, combined or derived parameters, relating e.g. fire distribution or seasonality to elevation class, fire occurrence to aspect, area burned to fire-severity class (Morrison and Swanson 1990), stand flammability to stand age (Heinselman 1981), to the maximum annual number of days where potential flame lengths exceeded 8 feet (Schmidt et al. 2002), and to condition classes of departure from the historic natural fire regime (Hann and Bunnell 2001; Hardy et al. 2001; Hann and Strohm 2003).

The number of potential parameters may lead to some confusion between those researchers using still the strict definition of FR and those using enlarged and more structured alternatives. In this paper, we suggest making it clear that there are different kinds of definition of FR, depending on the pursuit aim and the degree of complexity considered. At the highest level of complexity, i.e. reality, a fire regime is a sequence of fire events with some stable, recurrent or cyclic characteristics or properties (with all the conditions and consequences directly involved in burning processes) affecting a specified spatial and temporal window. In other words, in its widest sense, FR refers to a spatio-temporal unit in the fire distribution, that is, to everything about burning events in a defined zone and period in which fires have a certain uniformity and follow a rather regular pattern. At the opposite extreme of lowest complexity,Footnote 7 where resources, equipment or data availability are limited, for instance, when reconstructing paleofires, it may be necessary to define a fire regime unit according to just a few or even a single parameter. So for example Rowe and Jones (2000) discuss the existence or absence of the earliest fire events in pre-Carboniferous times, roughly 400 million years ago, and this single binary variable well represents the lowest level of complexity of FR. At the next level of complexity, Wang et al. (2005) were able to give general indications about fire regimes in continental China in the last 220,000 years, and identify a few shifts in terms of intensity or frequency of fires, by studying the black carbon mass sedimentation rates in three loess–paleosol sequences. Preece (1998) had only data on the extinction of certain fossil land snail taxa at his disposal, which suggested that fire occurrence increased on a South Pacific island during the medieval period, i.e. allowing only a very simple fire regime parameterization. Many of the early fire ecologists describing burning chronologies in different spatial or temporal windows also used just a few very simple variables to describe different units in fire distribution (Larsen and Delevan 1922; Lachmund 1923; Show and Kotok 1924; Gates 1930; Aldous 1934; Humphrey 1953; Curtis 1959; Weaver 1959; Cooper 1960).

This variability in applications of the term FR shows that it can be used as a broad collection of fire characteristics that may be organized, assembled and used in very different ways according to the needs of the users. Any definition based on a detailed list of parameters can only be one among many other possible definitions and only a description of parameter categories can attempt to be exhaustive. It is then duty and responsibility of each single user providing case by case a formal definition of the selected parameter and the frame conditions in which they are applied (Gill et al. 2002).

Figure 5 summarizes our proposal for a structuring of the most important categories. Some of the parameters belong to the core definition of FR sensu stricto, describing when, where and which fires occur (see Fig. 5a). Nearly all the early definitions of fire regime corresponded to this strict sense (Gill 1975, 1977; Aldrich et al. 1978; Christensen et al. 1981; Heinselman 1981; Sousa 1984, Christensen 1985).

In a strict sense sensu stricto a fire regime is a description by means of parameters of when, where and which fires occur (a). Used less strictly, i.e. in sensu lato, a fire regime may also include parameters that refer to the conditions of fire occurrence (b) and to the immediate effects of fires (c). Combining and analyzing the data of these three categories may result in further derived parameters (d). All parameters are facultative and should be used in a well-defined context

A second category of parameters refers to the conditions of fire occurrence (see Fig. 5b), that is all the factors recognized as “fire circumstances” in Booysen (1984, p. 364) and as “prerequisites for fires” in Bond and Van Wilgen (1996, p. 17) that directly determine the timing, size, magnitude and characteristics of fire events. We propose including these fire conditions as additional parameters in the broad definition of fire regime (sensu lato). In rare cases, some fire conditions have already been treated as FR parameters, e.g. fuel characteristics (Edwards 1984, p. 33; Geist 2005, p. 99), ignition sources (Kruger and Bigalke 1984; Trollope 1996; Lara et al. 2002, p. 338), fire weather (Edwards 1984, p. 33; Kruger and Bigalke 1984) and synergisms with other disturbances (White and Pickett 1985, p. 7; Agee 1993, p. 10). The distinction frequently made between “anthropogenic” and “natural fire regimes” suggests that the main causes and conditions can also be considered as components of the fire regime. In this category we could include other anthropogenic conditions such as the legal context in which fires occur (Pyne et al. 1996, p. 329), the system of man-made fuel breaks, or why and how people start fires (Davis et al. 1959, pp. 239–242; Hough 1993).

A third category of parameters that may be included in the broad definition of the FR refers to the immediate effects of fires (direct impact of fires on ecosystems, human goods and infrastructures, see Fig. 5c), which seems to be increasingly included in current definitions of FR. Kruger and Bigalke (1984) do not include immediate effects in their definition, but Mutch (1992, p. 128) has “ecological effects” on a list of fire regime parameters, even though not in the restricted set of the most important elements. Goldammer et al. (2001, p. 27), Bodrožić et al. (2005) and Romme (2005) all include the “immediate effects” of fires as components of a fire regime. The Glossary of Wildland Fire Terminology (National Wildfire Coordinating Group 2008, p. 76) also considers effects of fire as part of a FR. “Severity”, defined as the extent of physical change in an area caused by burning, is often recognized as a FR parameter (Sousa 1984, p. 375; Morrison and Swanson 1990, p. 1; Agee 1993, p. 19; Brown 1995, p. 172; Brown and Smith 2000).

Depending on the specific situation, parameters belonging to these categories can then be transformed and combined (see Fig. 5d). Derived and combined parameters have been used more in recent decades as increasingly complex instruments, methods and procedures for monitoring and modelling fire regimes have been developed. Examples of composite parameters include the analysis of burned areas according to fire-severity class (Morrison and Swanson 1990, p. 19), stand flammability related to the time since the last stand-replacing fire (Heinselman 1981, pp. 36–37), and the modelling of potential flame length for different weather scenarios (Beukema et al. 1999). Among the combined parameters, many classification systems have been used to distinguish and order by class different fire regimes (Frost 1998; Hardy et al. 1998; Morgan et al. 1998; Schmidt et al. 2002), although such classes may also be considered as meta-parameters that partly go beyond the notion of FR.

This kind of modular and flexible definition of fire regime we propose is needed to structure the very heterogeneous body of fire attributes currently in use and to reconcile the physical nature of fire with the socio-ecological context within which it occurs (Pyne 1984; Goldammer et al. 2001). This may also help to resolve some of the disagreements in the scientific community about how to define FR and which parameters to include.

The need to extend and complete the analysis of FR, by using more complex sets of variables and to take into account new additional parameters was already suggested by Buell and Cantlon back in 1953, with a sentence that nowadays looks really like a precursory statement. They stressed “the importance of the total burning regime” (p. 523) after they had observed striking differences in the vegetation on plots where roughly the same length time had elapsed since the last burn. Nearly 40 years later Mutch (1992, p. 128) put forward a similar idea defining FR as the “total pattern of fires”. This seems consistent with our broader definition (sensu lato) that considers not only the fire events themselves but also the conditions under which they occur and the impact they have.

Natural variability or regime shift?

Wildfires typically display a historical range of variability both in time and space (Morgan et al. 1994). The long-term periodicity of cyclical disturbance combined with long-term trends and even random variations often result in a gradual drift of the disturbance regime over time (Suffling and Perera 2004). In addition, fire regime components display a great spatial and temporal variability and heterogeneity, making their precise description or modelling a quite demanding task (e.g. Clark 1991, 1996; Johnson and Gutsell 1994; Clark et al. 2002; McCathry and Cary 2002; Gill et al. 2002, 2003). The definition of a historical or natural range of variability (or related expressions such as “natural range of variability”, “range of natural variability”) of a fire regime is thus crucial for providing a temporal and spatial scale of reference. This may represent a cornerstone in the contemporary paradigm of dynamic non-equilibrium of ecosystems (Landres et al. 1998, 1999), replacing the no longer plausible “balance of nature” concept with the more appropriate “flux of nature” idea (Pickett and Ostfeld 1995; Simus 2005).

Lertzman et al. (1998) define as “variability” the random fluctuations in fire regimes (noise inherent to the fire regime), and as “heterogeneity” a meaningful pattern over time and space (change in fire regime). This raises the question of how heterogeneous and variable a fire regime must be in a specific area or in a specific period before we start to speak about different fire regimes or about a shift in fire regime. Few attempts have been made so far to examine fire regime characteristics over time and space, as time intervals and space references are mostly set as frame conditions or defined on the basis of expert knowledge (e.g. ecoregions or meteorological regions). Fiorucci et al. (2008) proposed a numerical procedure to determine pyrologically similar regions on the basis of fire frequency and burnt area. Such an approach could easily also be applied to the partitioning of temporal units. Variability and heterogeneity in fire regimes has profound consequences not only for ecosystems affected by fire, but also for the possibility of making inferences about the nature of fire regimes. The development of a meaningful and statistically sound definition of FR for applications across different temporal and spatial scales appears therefore still far to be achieved.

Conclusions

The roots of the “fire regime” expression go further back in time than has generally been believed, and can be found in 19th century France and in the French colonies in Africa during the first half of the 20th century. The spread of the FR as a term coincided with the start of the general broad acceptance in the early 1960s of the ecological role of fires and the development of a new scientific discipline devoted to fire ecology. The concept of FR has not, however, remained static and has evolved continuously. Defining fire regime has helped fire ecologists and the scientific community to specify and assemble in a single concept the ecologically relevant characteristics of fire occurrence. From a practical point of view, FR-term also helps discussions of the role of fire among both technical and non-technical audiences, the determination of appropriate strategies for wildfire protection and prescribed fire use (Brown and Smith 2000; Goldammer et al. 2001), and anthropological and ecological research involving fires.

The definition of FR proposed here aims to contribute reconciliating the different interpretations of FR that currently exist, and to the development of a unified concept of fire regime.

Notes

As a general rule we use «italic» for French, "italic" for English, and italic for Latin. Italic is also used for often mentioned English terms like fire regime.

Pyne (1997) studied in-depth the history of "pastoral burning", i.e. the use of fire to clear land for grazing.

In a previous publication discussing the fire problem in Madagascar in-depth (Jumelle and de la Bâthie 1908) he did not use this expression, which is why we assume that he either learned or invented it between 1908 and 1912.

Hearle was not the only one. Others such as Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of the United States Forest Service, studied forestry in Nancy in 1889 and 1890. Pinchot was in many respects the predecessor of Carl Alwin Schenck who was one of the first using the FR expression in the USA.

The peak value for the percentage of FR in titles in the 1970s cannot be considered really significant as it occurred in only 2 out of 39 articles.

See "the simplest level of abstraction" in Frost (1984, p. 305).

References

Agee JK (1993) Fire ecology of Pacific Northwest forests. Island Press, Washington

Aldous AE (1934) Effect of burning on Kansas bluestem pastures. Kansas State College of Agriculture and Applied Science, Manhattan

Aldrich D, Kilgore B, Mutch R (1978) Fire in wilderness ecosystems. In: Hendee JC, Stankey GH, Lucas RC (eds) Wilderness management. USDA, Forest Service, Washington, pp 248–278

Anthony MR (1932) Actes administratifs. Bull Mus Natl Hist Nat 2(2):127–128

Aubréville A (1937) Les forêts du Togo et du Dahomey. Bull Com études hist sci Afr occident fr 20:1–112

Aubréville A (1938) La forêt coloniale. Les forêts de l’Afrique occidentale française. Société d’Éditions Géographiques, Maritimes et Coloniales, Paris

Aubréville A (1953) Les expériences de reconstitution de la savane boisée en Côte d’Ivoire. Bois For Trop 32:4–10

Aubréville A (1957) Échos du Congo Belge. Bois For Trop 51:28–39

Aubréville A (1973) Rapport de la Mission forestière anglo-française Nigeria–Niger. Bois For Trop 148:3–26

Belgrand E (1865) Notice sur le régime de la pluie sous le Bassin de la Seine. Dunod, Paris

Belgrand E (1872) La Seine. Etude hydrologiques. Régime de la pluie, des sources, des eaux courantes. Applications à l’Agriculture. Dunod, Paris

Bengtsson J, Nilsson SG, Franc A, Menozzi P (2000) Biodiversity, disturbance, ecosystem function and management of European forests. For Ecol Manag 132:39–50

Bergeron Y, Brisson J (1990) Fire regime in red pine stands at the northern limit of the species range. Ecology 71:1352–1364

Bergeron Y, Leduc A, Harvey BD, Gauthier S (2002) Natural fire regime: a guide for sustainable management of the Canadian boreal forest. Silva Fenn Monogr 36:81–95

Berry DPS, McCloskey ME, Gilligan JP (1969) Wilderness and the quality of life. In: Proceedings of the 10th wilderness conference, San Francisco, California, 1967

Beukema SJ, Reinhardt ED, Kurz WA, Crookston NL (1999) An overview of the fire and fuels extension to the forest vegetation simulator. In: Neuenschwander LF, Ryan KC (eds) Proceedings from the joint fire science conference and workshop, University of Idaho, June 15–17

Biswell HH (1989) Prescribed burning in California wildlands vegetation management. University of California Press, Berkeley

Biswell HH, Kallander HR, Komarek R, Vogt RJ, Weaver H (1973) Ponderosa fire management: a task force evaluation of controlled burning in ponderosa pine forests of central Arizona. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee

Bodrožić L, Marasović J, Stipaničev D (2005) Fire modeling in forest fire management. In: Proceedings of international conference: engineering for the future, CEEPUS Spring School, Kielce, Poland, June 2–16

Bond WJ, van Wilgen BW (1996) Fire and plants. Chapman & Hall, London

Booysen PdV (1984) Concluding remarks. Fire research. A perspective for the future. In: Booysen PdV, Tainton NM (eds) Ecological effects of fire in South African ecosystems. Springer, Berlin, pp 363–366

Bourlière F (1964) Committee Report. Management in National Parks. In: Adams AB (ed) Proceedings of the first world conference on national parks, Seattle, June 30–July 7, 1962. United States National Park Service, pp 364–365

Boyce JS (1921) Fire scars and decay. Timberman 22:37

Bradstock RA, Williams JE, Gill AM (eds) (2002) Flammable Australia: the fire regimes and biodiversity of a continent. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Brandis D (1899) Biological notes on Indian bamboos. Indian For 25:1–25

Bray WL (1906) Distribution and adaptation of the vegetation of Texas. Bull Univ Tex 82:1–108

Brown JK (1995) Fire regimes and their relevance to ecosystem management. In: Proceedings of the society of American foresters annual meeting, Washington, pp 171–178

Brown JK, Smith JK (eds) (2000) Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on flora. USDA, Forest Service, General Tech Report RMRS-GTR-42-Vol. 2, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Ogden

Buell MF, Cantlon JE (1953) Effects of prescribed burning on ground cover in the New Jersey pine region. Ecology 34:520–528

Buffault P, Fabre L-A (1904) Le mouvement forestier dans le sud-ouest. Le 3e Congrès du sud-ouest navigable (suite) de Narbonne. Rev eaux for 43:609–610

Byram GM (1959) Combustion of forest fuels. In: Davis KP, Byram GM, Krumm WR (eds) Forest fire: control and use. McGraw Hill, New York, pp 61–89

Caldararo N (2002) Human ecological intervention and the role of forest fires in human ecology. Sci Total Environ 292:141–165

Carcaillet C (1998) A spatially precise study of Holocene fire history climate and human impact within the Maurienne valley, North French Alps. J Ecol 86:384–396

Carle G (1920) Pâturages d’élevage à Madagascar. In: Chailley MJ, Fauchère A, Zolla D (eds) Compte rendu des travaux du Congrès d’agriculture coloniale, Paris 21–25 Mai 1918. Tome 4. Union coloniale française, Paris, pp 542–556

Champion HG (1936) Correspondence. Ground fires and fertility. Indian For 62:306–308

Champion HG (1954) Forestry. Oxford University Press, London

Champion HG, Griffith AL (1948) Manual of general silviculture for India. Oxford University Press, London

Chevalier A (1927) Chapitre V. Action de l’homme sur la végétation et associations végétales dues à son intervention. In: de Martonne E, Chevalier A, Cuénot L (eds) Traité de géographie physique. Tome troisième. Armand Colin, Paris, pp 1241–1280

Christensen NL (1985) Shrubland fire regimes and their evolutionary consequences. In: Pickett STA, White PS (eds) The ecology of natural disturbance and patch dynamics. Academic Press, New York, pp 85–100

Christensen NL (1993) Fire regimes and ecosystem dynamics. In: Crutzen PJ, Goldammer JG (eds) Fire in the environment. John Wiley and Sons, New York, pp 233–244

Christensen P, Recher H, Hoare J (1981) Responses of open forests (dry sclerophyll forests) to fire regimes. In: Gill AM, Groves RH, Noble IR (eds) Fire and the Australian biota. Australian Academy of Science, Canberra, pp 367–393

Clark JS (1991) Disturbance and population structure on the shifting mosaic landscape. Ecology 72:1119–1137

Clark JS (1996) Testing disturbance theory with long-term data: alternative life-history solutions to the distribution of events. Am Nat 148:976–996

Clark JS, Gill MA, Kershaw AP (2002) Spatial variability in fire regimes: its effects on recent and past vegetation. In: Bradstock RA, Williams JE, Gill AM (eds) Flammable Australia: the fire regimes and biodiversity of a continent. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 94–124

Clarke PGH, Clarke S (1996) Nineteenth century research on naturally occurring cell death and related phenomena. Anat Embryol 193:81–99

Clements FE (1916) Plant succession: an analysis of the development of vegetation. Carnegie Institution, Washington

Cola Alberich J (1953) La destrucción de los suelos del África Negra: sus consecuencias económicosociales. Cuad Estud Afr 21:37–53

Colonial Office (1939) Annual report by his majesty’s government in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the council of the league of nations on the administration of Tanganyika territory for the year 1938. His Majesty’s Stationery Office, London

Conedera M, Vassere S, Neff C, Meurer M, Krebs P (2007) Using toponymy to reconstruct past land use: a case study of ‘brüsáda’ (burn) in southern Switzerland. J Hist Geogr 33:729–748

Conedera M, Tinner W, Neff C, Meurer M, Dickens AF, Krebs P (2009) Reconstructing past fire regimes: methods, applications, and relevance to fire management and conservation. Quat Sci Rev 28:555–576

Cooling EN (1959) Softwood afforestation in copperbelt Miombo woodland. In: CSA meeting of specialists on open forests in tropical Africa. Ndola, Northern Rhodesia, 17–23 November 1959. Commission for technical co-operation in Africa South of the Sahara, pp 67–76

Cooper WS (1926) The fundamentals of vegetation change. Ecology 7:391–413

Cooper CF (1960) Changes in vegetation, structure, and growth of southwestern pine forests since white settlement. Ecol Monogr 30:130–164

Cooper CF (1961) Pattern in ponderosa pine forests. Ecology 42:493–499

Cowles HC (1901) The physiographic ecology of Chicago and vicinity. A study of the origin, development, and classification of plant societies. Bot Gaz 31:73–108 and 145–182

Craig JB, Brookfield P, Prokop J, Fisher JJ (1963) The Leopold committee report. Wildlife management in the national parks. Am For 69:32–35 and 61–63

Cumming JA (1964) Effectiveness of prescribed burning in reducing wildfire damage during periods of abnormally high fire danger. J For 62:535–537

Curtis JT (1959) The vegetation of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

Cuzacq P (1877) Des concessions de terrains communaux dans le département des Landes. Loi du 19 juin 1857, relative à l’assainissement et à la mise en culture des landes de Gascogne. Lasserre, Bayonne

Dandouau A (1922) Géographie de Madagascar. Larose, Paris

Davis KP, Byram GM, Krumm WR (1959) Forest fire: control and use. McGraw Hill, New York

Dawkins HC (1949) Timber planting in the Terminalia woodland of northern Uganda. Emp For Rev 28:226–247

de la Bâthie PH (1912) Histoire d’un changement de fasciés ou les modifications récentes ou actuelles de la flore malgache. Bull Acad Malgache 10:203–209

de la Bâthie PH (1921) La végétation malgache. Challamel, Paris

Decraene P (1994) Trois siècles de présence française en Inde: actes du colloque du 21 septembre organisé au Sénat par l’Association “Les comptoirs de l’Inde”. CHEAM, Paris

Delcourt A (1952) La France et les établissements français au Sénégal entre 1713 et 1763. Institut français d’Afrique noire, Dakar-Cahors

Delorme P (1866) Rhône inférieur. De l’endiguement des cours d’eau, de son utilité pour la conservation des intérêts agricoles, de l’influence qu’il exerce sur le régime des eaux et sur le fond des fleuves. Pitrat aîné, Lyon

Depelchin F (1887) Les forêts de la France. Alfred Mame, Tours

Dey DC, Hartman G (2005) Returning fire to Ozark highland forest ecosystems: effects on advance regeneration. For Ecol Manag 217:37–53

Duvergier JB (1857) Collection complète des lois, décrets, ordonnances, règlements et avis du Conseil d’État. Tome cinquante-septième. Pommeret et Moreau, Paris

Edwards D (1984) Fire regimes in the biomes of South Africa. In: Booysen PdV, Tainton NM (eds) Ecological effects of fire in South African ecosystems. Springer, Berlin, pp 19–37

Erhart H (1929) Sur la nature et l’origine des sols de Madagascar. Comptes Rendus Acad Sci 188:1561–1563

Erhart H (1935) Traité de pédologie. Tome 1: Pédologie générale. Institut Pédologique, Strasbourg

Fabre L-A (1904) Les incendies pastoraux et les associations dites «forestières» dans les Pyrénées centrales. Analyse d’un mémoire présenté au 3e congrès du Sud-Ouest Navigable à Narbonne. Bull Soc For Franche-Comté Belfort 7(7):544–546

Fabre L-A (1905) Les incendies pastoraux et les associations dites «forestières» dans les Pyrénées centrales. In: Le troisième congrès du sud-ouest navigable tenu à Narbonne les 27, 28 et 29 mai 1904. Privat, Toulouse, pp 244–255

Fairhead J, Leach M (1996) Misreading the African landscape. Society and ecology in a forest-savanna mosaic. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Falk DA, Swetnam TW (2003) Scaling rules and probability models for surface fire regimes in ponderosa pine forests. In: Thomas SC, Halpern CB, Falk DA (eds) Fire ecology, fuel treatments, and ecological restoration. Conference proceedings. Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, pp 301–317

Fanshawe DB (1959a) Burning experiments in Miombo woodland. In: CSA meeting of specialists on open forests in tropical Africa, Ndola, 17–23 November, pp 63–64

Fanshawe DB (1959b) Sylviculture and management of Miombo woodland. In: CSA meeting of specialists on open forests in tropical Africa, Ndola, 17–23 November, pp 101–104

Faust ME (1955) William L. Bray. Bull Torrey Bot Club 82:298–300

Fiorucci P, Gaetani F, Minciardi R (2008) Regional partioning for wildfire regime characterization. J Geophys Res 113:1–9

Fischer WR (1891) Forestry in North America. Nature 43:247–248

Ford-Robertson FC (1927) The problem of sal regeneration with special reference to the moist forests of the United Provinces. Indian For 53:500–511 and 560–576

Frost PGH (1984) The responses and survival of organisms in fire-prone environments. In: Booysen PdV, Tainton NM (eds) Ecological effects of fire in South African ecosystems. Springer, Berlin, pp 273–309

Frost CC (1998) Presettlement fire frequency regimes of the United States: first approximation. In: Pruden TL, Brennan LA (eds) Fire in ecosystem management: shifting the paradigm from suppression to prescription. Proceedings, 20th tall timbers fire ecology conference. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, pp 70–81

Furyaev VV (1996) Pyrological regimes and dynamics of the southern taiga forests in Siberia. In: Goldammer JG, Furyaev VV (eds) Fire in ecosystems of boreal Eurasia. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 168–185

Furyaev VV, Zabolotsky VI, Goldammer JG (2008) Dynamics of pyrological regimes at landscape stows in southern taiga of central Siberia in 18–20th centuries. Contemp Probl Ecol 1:250–256

Gates FC (1930) Aspen association in northern lower Michigan. Bot Gaz 90:233–259

Geist H (2005) The causes and progression of desertification. Ashgate, Farnham

Gill AM (1973) Effects of fire on Australia’s native vegetation. CSIRO, Division of Forest Research, Canberra

Gill AM (1975) Fire and the Australian flora: a review. Aust For J 38:4–25

Gill AM (1977) Management of fire prone vegetation for plant species conservation in Australia. Search 8:20–26

Gill AM, Allan G (2008) Large fires, fire effects and the fire-regime concept. Int J Wildland Fire 17:688–695

Gill AM, Groves RH (1981) Fire régimes in heathlands and their plant ecologic effects. In: Specht RL (ed) Ecosystems of the World, vol 9B. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 61–84

Gill MA, Bradstock RA, Williams JE (2002) Fire regimes and biodiversity: legacy and vision. In: Bradstock RA, Williams JE, Gill AM (eds) Flammable Australia: the fire regimes and biodiversity of a continent. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 429–446

Gill MA, Allan G, Cameron Y (2003) Fire-created patchiness in Australian savannas. Int J Wildland Fire 12:323–331

Gleason HA (1926) The individualistic concept of the plant association. Bull Torrey Bot Club 53:7–26

Glover PE, Jackson CHN, Robertson AG, Thomson WEF (1955) The extermination of the tsetse fly, Glossina morsitans wests, at Abercorn, Northern Rhodesia. Bull Entomol Res 46:57–67

Goldammer JG, Montag S, Page H (1997) Nutzung des Feuers in mittel- und nordeuropaischen Landschaften. NNA-Berichte 10:18–38

Goldammer JG, Mutch RW, Pugliese P, Davis R, Holmgren P (2001) FRA 2000 global forest fire assessment 1990–2000. FAO, Forestry Department, Roma

Gorrie RM (1936) Gradations in thinning intensity. Indian For 62:137–142

Gorrie RM (1952) Land use, soil erosion, and livestock problems in Ceylon. J Range Manag 5(4):215–220

Gorrie RM (1966) Peat as a highland resource. Scott For 20:165–174

Gorski S, Marra M (2002) Programmed cell death takes flight: genetic and genomic approaches to gene discovery in Drosophila. Physiol Genomics 9:59–69

Greswell FA (1926) The constructive properties of fire in chil (Pinus longifolia) forests. Indian For 52:502–505

Hann WJ, Bunnell DL (2001) Fire and land management planning and implementation across multiple scales. Int J Wildland Fire 10:389–403

Hann WJ, Strohm DJ (2003) Fire regime condition class and associated data for fire and fuels planning: methods and applications. In: Thomas SC, Halpern CB, Falk DA et al (eds) Fire ecology, fuel treatments, and ecological restoration. Conference proceedings. Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, pp 397–433

Hardy CC, Menakis JP, Long DG, Brown JK, Bunnell DL (1998) Mapping historic fire regimes for the western United States: integrating remote sensing and biophysical data. In: Greer JD (ed) Natural resources management using remote sensing and GIS: proceedings of the 7th forest service remote sensing applications conference April 6–10. Am Soc Photogramm Remote Sens, Bethesda, pp 288–316

Hardy CC, Schmidt KM, Menakis JM, Samson NR (2001) Spatial data for national fire planning and fuel management. Int J Wildland Fire 10:353–372

Harper RM (1911) The relation of climax vegetation to islands and peninsulas. Bull Torrey Bot Club 38:515–525

Harper RM (1913) A defense of forest fires. Lit Digest 47:208

Hearle N (1888) The grazing question in Jaunsar. Indian For 14:243–250

Heinselman ML (1973) Fire in the virgin forests of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, Minnesota. Quat Res 3:329–382

Heinselman ML (1978) Fire in wilderness ecosystems. In: Hendee JC, Stankey GH, Lucas RC (eds) Wilderness management. U.S. Forest Service, Washington, pp 249–278

Heinselman ML (1981) Fire intensity and frequency as factors in the distribution and structure of northern ecosystems. In: Mooney HA, Bonnicksen TM, Christensen NL et al (eds) Proceedings of the conference: fire regimes and ecosystem properties, 1978 December 11–15, Honolulu. USDA Forest Service, Washington, pp 7–57

Henry AJ (1919) Increase of precipitation with altitude. Mon Weather Rev 47:33–41

Henry AJ (1923) Hernandez on the temperature of Mexico. Mon Weather Rev 51:497–509

Heurtier N, Denjoy J-F-P (1857) Projet de loi présenté au Corps législatif le 28 avril 1857. Exposé des motifs. Monit Univers

Hough JL (1993) Why burn the bush? Social approaches to bush-fire management in West African national parks. Biol Conserv 65:23–28

Hoxie GL (1910) How fire helps forestry. Suns Mag 25:145–151

Humbert JH (1927) La destruction d’une flore insulaire par le feu. Principaux aspects de la végétation à Madagascar. Pitot, Tananarive

Humbert JH (1931) La végétation des hautes montagnes de l’Afrique centrale équatoriale. Terre vie 1:205–219

Humbert JH (1933) Types de végétation primaire et secondaire en Afrique équatoriale. In: Comptes Rendus du XIIIe Congrès International de Géographie, Paris 1931. Tome II. Deuxième fascicule. Armand Colin, Paris, pp 834–838

Humbert JH (1936) Conférence par M. H. Humbert sur la protection de la nature, considéré du point de vue biologique, dans les pays tropicaux et subtropicaux. In: Sirks MJ (ed) 6th International Botanical Congress, Amsterdam, 2–7 September, 1935. Proceedings. Volume 1. Brill, Leiden, pp 91–94

Humbert JH (1940) La protection de la nature dans les territoires d’outre-mer pendant la guerre. Séance du 21 février. Comptes rendus mens séances Acad sci outre-mer 375–382

Humbert JH (1947) La végétation de Madagascar. In: Guernier E, Froment-Guieysse G (eds) L’Encyclopédie coloniale et maritime. Madagascar. Tome I, Paris, pp 47–62

Humbert JH (1949) La dégradation des sols à Madagascar. Bull Agric Congo Belg 40:1141–1162

Humbert JH (1953) Le problème du recours aux feux courants. Revue Int Bot Appl Agron Trop 32:19–28

Humbert JH (1960) Henri Perrier de la Bâthie (1873–1958). Notulae Syst 16:1–6

Humphrey RR (1953) The desert grassland, past and present. J Range Manag 6:159–164

Humphrey RR (1962) Range ecology. Ronald Press, New York

Ingalsbee T (2002) Wildfire paradoxes. Or q 18–23

Jepson WL (1909) The trees of California. Curtis & Welch, San Francisco

Johnson EA, Gutsell SL (1994) Fire frequency models, methods and interpretations. Adv Ecol Res 25:239–287

Johnson EA, Van Wagner CE (1985) The theory and use of two fire history models. Can J For Res 15:214–220

Jumelle HL, de la Bâthie PH (1908) Notes biologiques sur la végétation du nord-ouest de Madagascar. Les Asclépiadées. Ann Mus Colon Marseille 2:131–239

Keller F, Lischke H, Mathis T, Möhl A, Wick L et al (2002) Effects of climate, fire, and humans on forest dynamics: forest simulation compared to the palaeological record. Ecol Model 152:109–127

Kilgore BM (1976) From fire control to fire management. An ecological basis for policies. In: Transactions of the 41st North American wildlife and natural resources conference. Wildlife Management Institute, Washington, pp 477–493

Kilgore BM (2007) Origin and history of wildland fire use in the U.S. National Park system. George Wright Forum 24:92–122

Komarek EV (1963) Proceedings second annual tall timbers fire ecology conference. March 14–15. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee

Komarek EV (1964) Proceedings third annual tall timbers fire ecology conference. April 9–10. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee

Komarek EV (1965) Fire ecology—grasslands and man. In: Proceedings fourth annual tall timbers fire ecology conference. March 18–19. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, pp 169–220

Kruger FJ, Bigalke RC (1984) Fire in Fynbos. In: Booysen PdV, Tainton NM (eds) Ecological effects of fire in South African ecosystems. Springer, Berlin, pp 67–114

Kuhnholtz-Lordat G (1938) La terre incendiée: essai d’agronomie comparée. Maison carrée, Nimes

Kuhnholtz-Lordat G, Heim R (1958) L’écran vert. Editions du Muséum, Paris

Kull CA (2004) Isle of fire. The political ecology of landscape burning in Madagascar. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Lachmund HG (1923) Bole injury in forest fires. J For 21:723–731

Lageard JGA, Thomas PA, Chambers FM (2000) Using fire scars and growth release in subfossil Scots pine to reconstruct prehistoric fires. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 164:87–99

Landres PB, White PS, Aplet G, Zimmermann A (1998) Naturalness and natural variability: definitions, concepts, and strategies for wilderness management. In: Kulhavy DL, Legg MH (eds) Wilderness and natural areas in eastern America. Stephen F. Austin University, Nacogdoches, pp 41–50

Landres PB, Morgan P, Swansonc FJ (1999) Overview of the use of natural variability concepts in managing ecological systems. Ecol Appl 9:1179–1188

Lara A, Wolodarsky-Franke A, Aravena JC, Cortés M, Fraver S (2002) Fire regimes and forest dynamics in the lake region of South-Central Chile. In: Veblen TT, Baker WL, Montenegro G, Swetnam TW (eds) Fire and climatic change in temperate ecosystems of the western Americas. Springer, Berlin, pp 322–342

Larsen JA, Delevan CC (1922) Climate and forest fires in Montana and northern Idaho, 1909 to 1919. Mon Weather Rev 49:55–68

Lebrun JPA (1936) Répartition de la forêt equatoriale et des formations végétales limitrophes. Ministère des Colonies, Bruxelles

Leiberg JB (1899) San Gabriel, San Bernardino, San Jacinto forest reserves. In: Gannett H (ed) 19th annual report of the U.S. Geological Survey. Part 5. Forest reserves. Government Printing Office, Washington, pp 359–370

Leopold AS, Cain SA, Cottam CM, Gabrielson IN, Kimball TL (1963) Study of wildlife problems in national parks: wildlife management in the national parks. In: Trefethen JB (ed) Transactions of the 28th North American wildlife and natural resources conference, March 4–6. Wildlife Management Institute, Washington, pp 28–45

Lertzman K, Fall J, Dorner B (1998) Three kinds of heterogeneity in fire regimes: at the crossroads of fire history and landscape ecology. Northwest Sci 72:4–23

Little S, Moore EB (1953) Severe burning treatment tested on lowland pine sites. USDA, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, Upper Darby

Lockshin RA (1963) Programmed cell death in an insect. Dissertation, Harvard University

Lorenz EN (1963) Deterministic nonperiodic flow. J Atmos Sci 20:130–141

Mathew KS (1999) French in India and Indian nationalism (1700 AD–1963 AD). BR Publishing Corporation, Delhi

Maunder ER (1954) Dr. Carl Alwin Schenck, German pioneer in the field of American forestry. Pap Mak 23:17–30

McCathry MA, Cary GJ (2002) Fire regimes in landscapes: models and realities. In: Bradstock RA, Williams JE, Gill AM (eds) Flammable Australia: the fire regimes and biodiversity of a continent. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 77–93

McVean DN, Lockie JD (1969) Ecology and land use in upland Scotland. University Press, Edinburgh

Methven IR (1978) Fire research at the Petawawa forest experiment station: the integration of fire behavior and forest ecology for management purposes. In: Dubè DE (ed) Fire ecology in resource management: workshop proceedings, December 6–7, 1977. Northern Forest Research Centre, Edmonton, pp 23–27

Moore AW (1960) The influence of annual burning on a soil in the derived savanna zone of Nigeria. In: Transactions of the 7th international congress of soil science, 7th session. ISSS, Madison, pp 257–264

Moore NW (1962) The heaths of Dorset and their conservation. J Ecol 50:369–391

Morgan P, Aplet GH, Haufler JB, Humphries HC, Moore MM et al (1994) Historical range of variability: a useful tool for evaluating ecosystem change. J Sustain For 2:87–111

Morgan P, Bunting SC, Black AE, Merrill T, Barrett S (1998) Past and present fire regimes in the interior Columbia river basin. In: Close K, Bartlette RA (eds) Fire management under fire (adapting to change): proceedings of the 1994 interior west fire council, 1994 November 1–4. Int Assoc Wildland Fire, Fairfax, pp 77–82

Morris WG, Mowat EL (1958) Some effects of thinning a ponderosa pine thicket with a prescribed fire. J For 56:203–209

Morrison PH, Swanson FJ (1990) Fire history and pattern in a cascade range landscape. Pacific Northwest Research Station, Portland

Moss R (1969) A comparison of red grouse (Lagopus L. scoticus) stocks with the production and nutritive value of heather (Calluna vulgaris). J Anim Ecol 38:103–122

Moureaux C (1950) Reconnaissance pédologique d’une station forestière (Marohoga près Majunga). Mem Inst Sci Madag Ser D 2:123–150

Moureaux C, Tercinier G (1956) Notice sur la carte pédologique de reconnaissance au 1/200000e, feuille No 19: Maevatanana. Mem Inst Sci Madag Ser D 7:23–91

Muir J (1901) Our national parks. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Mutch RW (1992) Sustaining forest health to benefit people, property, and natural resources. In: American forestry—an evolving tradition. Proceedings of the 1992 society of American foresters national convention, October 25–27. Soc Am For, pp 126–131

National Wildfire Coordinating Group (2008) Glossary of wildland fire terminology. November 2008. USDA, NWCG Incident Operations Standards Working Team, Boise

Nelson JG, Scace RC (1969) The Canadian national parks: today and tomorrow. In: Proceedings of a conference, October 9th–15th, 1968. National and Provincial Parks Association of Canada, University of Calgary, Calgary

Newell ND (1967) Revolutions in the history of life. In: Albritton CC Jr, Hubbert MK, Wilson LG et al (eds) Uniformity and simplicity. A symposium. Geological Society of America, New York, pp 63–91

Niemeyer JC, Kerstein AR (1997) Burning regimes of nuclear flames in SN Ia explosions. New Astron 2:239–244

Niering WA, Goodwin RH (1962) Ecological studies in the Connecticut arboretum natural area I. Introduction and a survey of vegetation types. Ecology 43:41–54

Noble JC, Grice AC (2002) Fire regimes in semi-arid and tropical pastoral land: managing biological diversity and ecosystem function. In: Bradstock RA, Williams JE, Gill AM (eds) Flammable Australia: the fire regimes and biodiversity of a continent. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 373–400

Offermann PPM (1953) Organisation de la protection de la faune. In: Proceedings of the third international conference for the protection of the fauna and flora of Africa: Bukavu, 26–31 October, 1953, Belgian Congo. Commission for technical co-operation in Africa South of the Sahara, Bruxelles, pp 309–326