Abstract

Sri Lanka’s population is predicted to age very fast during the next 50 years, bringing a potential slowdown of labor force growth and after 2030 its contraction. Based on a large and detailed survey of old people in Sri Lanka, conducted in 2006, the paper examines labor market consequences of this process, focusing on employment outcomes of old workers and the reasons and determinants of labor market withdrawal. The paper finds that a vast majority of Sri Lankan old workers are engaged in the informal sector, work long hours, and are paid less than younger workers. Moreover, using hard evidence, it shows that labour market duality characterizing most developing countries carries over to old age: (i) previous employment is the most important predictor of the retirement pathway; (ii) older workers fall into two categories: formal sector workers, who generally stop working before age 60 because of mandatory retirement regulations, and casual workers and the self-employed, who, due to poverty, work till very old ages and stop working primarily because of poor health; and (iii) the option of part-time work is used primarily by former formal sector workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In slightly more than two decades, Sri Lanka’s population will be as old as Europe’s or Japan’s today, but its per capita income will be much lower. Indeed, while population aging is a universal phenomenon, it looms particularly large for Sri Lanka: not only is its current share of old people larger than the share of old people in other South Asian countries (and of many other developing countries), but Sri Lanka is also expected to age very fast—much faster than its regional comparators although not as fast as East Asian countries (see Fig. 1). As a consequence, assuming unchanged labor force participation rates, labor supply is projected to reduce its growth initially and to start shrinking in about 30 years.

In developed countries, challenges of population aging are associated primarily with the negative impact of aging on economic growth, and the need to plan for additional public and private outlays for old age income support and health care (MacKellar 2000). In Sri Lanka, a developing country, these challenges are compounded by several facts.Footnote 1 First, in 2006 only a tenth of the old people received pensions as their major source of income and a third received non-pension government assistance, so that most relied on family support as key for their wellbeing. With only one-third of the labor force presently covered by social security programs (World Bank 2007), the need for family support is likely to remain high in the coming decades. Second, rapid aging and modernization may put a strain on the traditional family support to old people. The modernization of Asian societies is associated by several mechanisms that affect family support of old people (Hermalin 2002)—lower fertility translating into fewer children available to provide familial support; higher education levels leading to differences in attitudes and perceptions of obligations to provide familial support; increased female labor force participation reducing the number of caregivers available to provide support to older family members; and rural–urban migration drawing younger persons out of rural areas to find employment.Footnote 2 Third, the health system is insufficiently focused on the health care needs of old people and is constrained by the lack of resources and their inequitable distribution (World Bank 2008). And fourth, population aging may well translate into shrinking of the labor force, prompting questions of how to promote longer working lives. Moreover, as a consequence of the low coverage by social security programmes and limited family support, many old people are forced to continue working late in their lives to meet their financial needs, and labor market choices of these people need to be improved.

To shed light on policy options available to Sri Lanka given its imminent population aging, this paper focuses on two sets of questions related to labor market outcomes of old workers (defined here as those over 60). The first set relates to employment and wages of old workers, thus investigating how old people are treated in the labor market (cross-section analysis): Is their employment formal or informal? In what sectors and occupations are they employed? Are they full- or part-time workers? How many hours do they work? What is their pay relative to young workers? The second set of questions relates to the reasons for and determinants of retirement. In this part we examine how personal and family characteristics and aspirations, material and health status, geographic location, and work career affect the way old workers withdraw from the labor market, that is, their retirement pathways.

In regard to how old workers are treated in the labor market, the paper finds that a vast majority of Sri Lankan old workers are engaged in the informal sector, work long hours, and are paid less than younger workers. In regard to determinants of retirement, the paper—one of the first providing hard evidence about this phenomenon—shows that labor market duality characterizing labor markets of most developing countries carries over to old age: (i) previous employment is the most important predictor of the manner of retirement; (ii) older workers fall into two categories: civil servants and formal private sector workers, who generally stop working before reaching age 60 because of mandatory retirement regulations, and casual workers and the self-employed, who are forced to work until very old age (or death) due to poverty and who stop working primarily because of poor health; and (iii) the option of part-time work is used primarily by workers who held regular jobs in their prime age employment, but not by casual workers and the self-employed.

Policy implications of the paper take two forms. First, the paper describes measures to increase the labor force participation and productivity of old workers, in view of pending slowdown of labor supply caused by population aging. Second, the paper also points to areas important to improve labor market choices available to old workers.

The paper is organized as follows. To set the stage, “Population Aging and the Labour Supply of Elderly” presents labor supply implications of population aging and the present labour market outcomes for old workers in the country. “Data and Methodology” describes data and methodology, and “Results” presents the empirical analysis. “Conclusions and Policy Implications” concludes with policy implications.

Population Aging and the Labour Supply of Elderly

This section provides the study context by presenting trends of population ageing in Sri Lanka, describing how that affects the labour supply, and presenting trends in labor force participation and unemployment of old workers.

Labour Supply Implications of Population Aging

Demographic projections show that Sri Lanka’s population is likely to age rapidly in the next 50 years. The main drivers of this process are low and declining fertility and increasing life expectancy. The total fertility rate (the number of children that the average woman bears during her lifetime) fell below the replacement level of 2.1 by 1994 and it has continued to fall, reaching 1.7–1.9 in the 2000s. Gains in life expectancy will also contribute their share. Present trends indicate that rising life expectancy of Sri Lankans will reach the current average OECD level of 77.8 years by 2050 (OECD 2005); current life expectancy for Sri Lankan men and women (69 years and 77 years, respectively) is higher than in most developing countries. Sri Lanka’s projected demographic aging is characterized by an increase in the share of old people, with the share of people aged 60 years and above projected to increase from the current 11% to 17% in 2020 and to 29% in 2050 (Fig. 1), and the share of very old people (80 years and more) is also expected to strongly increase. Because in the next two to three decades the increasing old age dependency ratio (the proportion of population aged 60 years or more versus the proportion aged 15–59 years) is expected to be roughly matched by a fall in the child dependency ratio (the proportion of the population aged less than 15 years versus the proportion aged 15–59 years), the overall dependency ratio is projected to start increasing rapidly after 2040 (Fig. 2).

Projections show that population aging is expected to translate into a slowdown of Sri Lankan labor force growth and later into its contraction, while also affecting its composition. Applying constant current labor force participation rates to population projections, it can be shown that the labor force will stop growing around 2030, and will thereafter start to shrink, dropping to the current size of the labor force in about 30 years (see details in Vodopivec and Arunatilake 2008). Population aging will also significantly change the age composition of the labor force, with the share of workers younger than 30 years shrinking considerably and the share of those older than 50 years increasing significantly.

Labour Force Participation and Unemployment of Old People

During 1992–2004, Labor Force Survey data show that the labor force participation (LFP) of old workers remained stable, men’s participation rate by far exceeded women’s, and the withdrawal from a labor market occurred rather late in the life cycle (Fig. 3; because over time this pattern changed very little, we show only the pattern for 2004). Workers were withdrawing from the labor market rather late in the working career—starting with the age group 60–69 for males and 50–59 for females. For males, LFP rates for all age groups in the prime age (20–59) exceeded 80%, dropping to around 50% in the age group 60–69 and to around 20% in the age group over 70. Withdrawal for the women started somewhat earlier—in 2004, LFP rates in the age group 40–49 were about 44%, dropping to 33% in the age group 50–59, to 14% in the age group 60–69, and to 3% in the age group over 70 (Vodopivec and Arunatilake 2008).

International comparisons show that Sri Lanka’s labor force participation rates for old people lag behind the rates of its regional comparators while mostly exceeding those in developed countries.Footnote 3 Labor force participation of older men is lower than in other countries in the region (India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan), and so is participation of women, except that women’s participation rate in Sri Lanka exceeds the one in predominantly Muslim countries (Pakistan and Bangladesh). Interestingly, the LFP of the old people in Sri Lanka also lags behind the rates of Thailand and Japan, but they exceed those in Western Europe (Vodopivec and Arunatilake 2008).

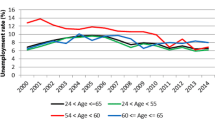

Unemployment among old Sri Lankans is a rather uncommon phenomenon. During 1992–2004, unemployment rates for males aged 60–69 were typically well below 1% and virtually zero for those over 70 years; unemployment rates for old women were even lower (Vodopivec and Arunatilake 2008). These figures reflect the fact that when losing their jobs, old workers tend to withdraw altogether from the labor market (the phenomenon called “hidden unemployment” by OECD 2006). Unemployment rates are rapidly falling with age for both men and women. In 2004, 15–19 year olds had the highest unemployment rates, amounting to 26 and 37%, respectively, for men and women, with unemployment rates for older age groups monotonically decreasing and reaching single digit numbers already in the age group of 30–39 year olds (see Vodopivec and Arunatilake 2008, for details). Unemployment rates of old Sri Lankans are in line with those of regional comparators such as India and Thailand and lag substantially behind developed countries (in OECD, unemployment rates in 2004 for workers aged 50–64 ranged from 2% in Norway to 11% in Germany, OECD 2006).

Data and Methodology

Below we explain the data sources and methodology used in the empirical analysis that follows.

Data Sources

The primary data used by the paper is the 2006 Sri Lanka Aging Survey (2006 SLAS), conducted by the World Bank. The survey collected detailed information about personal and family characteristics of old people and their wealth, and had separate labor and health modules. In addition to asking about their current employment status, respondents were also asked retrospectively about age of retirement from their full- or part-time job, as well as employment status when they were in their early fifties, that is, at the end of the prime of their work career, rendering the work history data a panel nature.

The survey is based on a representative sample of 2,413 Sri Lankan old people (defined as persons 60 years old or above), residing in 260 communities around the island that were not affected by the ethnic conflict. The sampling process was based on the selection of districts (those affected by ethnic conflict or escalated tensions were eliminated) and communities—Primary Sampling Units within districts (based on the 2001 Census of Housing and Population). The survey itself consisted of two stages. In the first stage, basic personal information on household members in all households in the selected communities was obtained. In the second stage, 2,115 households with elderly (some with more than one old person) were selected based on the listing of all household members obtained in the first stage. Field work commenced in February 2006 and was completed by April 2006. On average, an interview took about one and a half hours to complete.Footnote 4

Methodology

Empirical analysis below consists of two parts, the first examining the employment outcomes of old workers (cross-section analysis), and the second the reasons and determinants of retirement (partly based on panel analysis). The first part uses descriptive analysis in which we present the occurrence and incidence of events of interest (such as type and sector of employment) by specific attributes.

The second part—reasons and determinants of retirement—uses three tools. First, we present and analyze declared reasons for retirement by old people, based on questions to that effect asked by the 2006 SLAS. Second, to investigate labor market duality patterns, we trace retirement pathways of groups of workers with distinct (as hypothesized by us and detailed below) working careers. And third, we perform a multinomial estimation of determinants of transition from full-time work to part-time work and to complete retirement.

The analysis of retirement pathways of different groups of workers distinguishes the following four groups of workersFootnote 5:

-

Regular public sector workers (i.e., regular workers of public sector, public corporations, or boards and the cooperative sector),

-

Regular private sector workers (i.e., regular workers of both the formal and the informal private sector),

-

Casual workers (i.e., casual and contractual workers), and

-

Self-employed (i.e., employers and the self-employed).

A regular public sector worker is a worker with a permanent contract, while a casual worker is a worker who is employed to conduct a specific task—such as painting a building—on a temporary basis. Contractual workers are workers employed under a contract for short-term assignments. Self-employed are workers who work for themselves. These include agricultural workers who work on their own farms. In this study, public and private sector workers who receive retirement benefits and are entitled to paid annual leave are considered as formal workers; other workers in the formal sector,Footnote 6 workers in the private informal sector enterprises, unpaid family workers, and workers without a permanent employer are considered as informal workers. Formal private sector comprises registered enterprises that keep formal written accounts and employ more than 10 regular employees.

For this analysis, we selected 1,060 workers who held full-time jobs at the age of 54, and traced their work activity continuously into their old age. According to the pre-retirement employment status, the total sample of 1,060 individuals comprise 276 regular public sector workers, 138 regular private sector workers, 223 casual workers, and 424 self-employed (the data are right censored). Note that the analysis of the retirement pathways exploits the panel nature of the 2006 SLAS.

The multinomial estimation is used to identify the determinants of a person’s status at the age of 61–65. The sample consists of the same 1,060 persons who held full time jobs at the age of 54 as in the previous analysis. . We allow three possibilities for a person’s status at the age of 61–65 (that is, our dependent variable can take three values):

-

Completely retiring upon reaching 61 years and not working when aged 61–65 (in our sample, 382 individuals); this transition was taken as a baseline.

-

Working at least some time during ages 61–65, either part time or full time if not throughout the period (in our sample, 208 observations).

-

Working continuously full time during ages 61–65 (in our sample, 470 observations).

Among explanatory variables, labor market factors as well as family, demographic, and personal characteristics are included (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics of independent variables). Of the sources of income considered in the study, inclusion of financial or in kind family assistance could be endogenous, if one believes that the amount of help given by the family varies according to other sources of income, and the health status of old people. Hence, instead of using family assistance, we use a proxy variable, which indicates whether individuals have access to help if they need it.

Results

Below we present our empirical analysis based on 2006 SLAS data. As mentioned, it consists of two parts—the first presents the employment outcomes of old workers and investigates into the reasons and determinants of retirement. The first part is purely descriptive and the second examines the pathways to retirement and tries to probe into mechanisms responsible for certain employment outcomes.

Employment Outcomes of Old People

Type of Employment

The vast majority of old workers are engaged in the informal private sector. The main exceptions are men in their early sixties, with a small share of them working for the government or in the formal private sector (to save the space, we omit graphical presentation of results; for further details, see Vodopivec and Arunatilake 2008). Moreover, more than half of old workers, both males and females, are self-employed. The remaining majority are casual workers, with less than 3% of old people working as regular workers, mostly workers in their early sixties.

Sector of Work, Industry and Occupation

Old workers, both males and females, predominantly work as skilled workers in agriculture, manufacturing, and wholesale and retail trade. A fair proportion of them, particularly women, work at the bottom of the occupational ladder (in elementary occupationsFootnote 7), and a small proportion as professional workers. Not surprisingly, the composition of old workers by occupation changes little with age, as does sector of work, except that the share of workers in agriculture is reduced. While the sector of work and status for old workers working part time does not differ much from full-time workers, a larger share of part-time workers work as professional and skilled workers, possibly because they can afford to do so (see details in Vodopivec and Arunatilake 2008).

Employment Status

Most of the old workers have full-time rather than part-time jobs. As presented above, as they age, fewer and fewer workers remain employed. But if they do, they tend to work in full-time jobs rather than part-time. In our survey of old people, 30% of males were employed, of whom two thirds were in full-time employment and only a third in part-time employment; only 5% of women were employed, with 60% of them in full-time employment. The proportion of part-time employment among old workers was the lowest in the 60–64 age group and increased for older groups of workers, with the share of part-time workers exceeding the share of full-time workers in the 75–79 age group.Footnote 8

Number of Hours Worked

The number of hours worked is lower at higher ages, although those old workers that stay active work long hours. On average, the weekly number of hours of work provided by all old males (retired or working) decreased from 23 for 60–63 year olds to 10 for 72–75 year olds.; and by old female workers, from five to 2 h, for the same age groups. At the same time, workers staying active reduced the number of hours worked as they age, men from the average of 47 in their early sixties to 36 in the 72–75 year group, and women from 35 to 29 for the same age groups. Despite these reductions, the average number of hours of work for those workers who remained employed is large even at very old ages. Old workers in part-time jobs also work long hours—in our sample (2006 SLAS), they on average work only 12 h less than old workers in full-time jobs (36 h compared to 48).

Pay of Old Workers

In comparison to younger workers, old workers are paid less, particularly in the public sector. Wages for workers aged 65 and above are only a fraction of wages of the best paid group of workers—workers in their late 50s and early 60s, in the public sector, and in their 30s, in the private sector (Fig. 4). Particularly strong reduction of wages of older workers occurs in the public sector, with workers aged 65 and over earning barely over one-third of what the workers in the 60–65 group are earning, and only about 20% of what workers in the 55–59 year group are earning (the latter applies for women only). In the private sector, the reduction of wages for workers above 65 years of age is more modest. Interestingly, except for women in the public sector, wages of workers in the 60–64 year group are higher than wages of the 55–59 year group.Footnote 10 One salient feature of the age-wage profiles is the fact that both men’s and women’s profiles of the private sector are much flatter than the ones in the public sector. Many OECD countries have hump-shaped age–wage profiles, but there are many exceptions, reflecting different institutional wage-setting and other arrangements (see OECD 2006).

Declared Reasons and Determinants of Retirement

To shed further light on the above outcomes, this subsection investigates the declared reasons for retirement and tries to identify and empirically estimate determinants of transition from the working life. One specific approach that is followed is the investigation of retirement pathways—labor market arrangements between full-time work late in the working career and a complete withdrawal from the labor market. In contrast to the above, cross-sectional analysis, this analysis selects those individuals from the 2006 SLAS that had full-time, stable jobs in their early fifties and follows them into their old age, thereby exploiting the panel nature of the survey (1,060 workers were selected, see the “Methodology” section).

The following questions are being addressed: What are the reasons for retirement? For example, how does family conditions, individual’s wealth and sources of support influence the decision to retire? How do health status and other personal considerations (such as the desire to provide childcare for grandchildren) affect retirement? How does mandatory retirement age affect retirement? Moreover, given the deep segmentation of the Sri Lankan labor market, one can conjecture that working careers themselves determine the fate of workers in their old age. If so, the question emerges whether one can discern separate pathways along the public-private and formal-informal margins, and in what dimensions such pathways differ in the timing of retirement? Speed of retirement—how quickly does the withdrawal from the labor market happen, abruptly or gradually via part-time employment? What are the changes in sectoral and occupational careers?

These questions are addressed in three ways. First, we present the declared reasons for retirement, based on questions to that effect in the 2006 SLAS. Second, to investigate the duality patterns, we trace retirement pathways for groups of workers having distinct working careers: regular public sector workers, regular private sector workers, casual workers, and self-employed, focusing on the timing of their retirement, speed of retirement, and changes of sector of work or occupation occurring in old age. And third, we perform a multinomial estimation of determinants of transition from full-time work to part-time work and to complete retirement.

Declared Reasons for Retirement

2006 SLAS allows us to examine direct response of old people about their reasons for retirement. Those responses show that most workers are pushed away from jobs, but while for regular public and private sector workers the main reason is mandatory retirement age, for casual and self-employed workers, it is poor health. For regular public sector workers, the main reason for retirement at any age is work-related, primarily reaching mandatory retirement age (see Fig. 5). The same holds true for regular private sector workers, except for those aged 61–70. Overall, slightly over a quarter of regular workers in the private sector cited reaching mandatory retirement age as a reason for retirement from full-time work. On the other hand, by far the most compelling reason for retirement at all ages for casual workers and the self-employed is poor health (a small exception is casual workers aged 55–59, where work-related reasons slightly overweight health reasons). Interestingly, personal reasons figure more prominently for casual workers and the self-employed than for regular workers.

The main declared reasons for retirement are on the push side: poor health and reaching mandatory retirement age, for both males and females (See Table 2).Footnote 11 Among the push factors, work and travel stress, as well as the closure of businesses were also important factors affecting the decision to retire. Among the declared pull factors, “doing other things (hobbies)” was an important reason for retirement, especially for females. Only females found family obligations a very important reason for complete retirement; however, it was a relevant factor only for a small proportion of females. This indicates that obligations of childcare and care for old persons do not have a large effect on retirement decisions.

Earning additional income was the main reason for part-time employment for most workers. Three in four old people in part-time employment continue to work to earn additional income. More females than males consider the additional income from part-time employment as the main reason for continued employment. A small percentage also worked part time to keep themselves occupied (6%) and to be in touch with their profession (3%). A large share of old people working part time does so involuntarily, as 80% of those who retired after doing some part-time work indicated that they would have liked to stop work completely after retirement from full-time work. (On the other hand, over a quarter of the surveyed old people indicated that they would have liked to continue doing some paid work when they retired from their full-time jobs).

Analysis of the Pathways to Retirement

The results below confirm that pathways to retirement show strong dual patterns. The majority of regular workers in public and private sector retire early, most of them before they reach 60, and for work-related reasons (including mandatory retirement); in contrast, a large share of self-employed and casual workers continues to work full-time into very old ages, and most of them withdraw from employment for health reasons. The option of part-time work is also used primarily by workers who held regular jobs in their prime age employment, but not by casual workers and self-employed. The results show that labor market duality, the hallmark of labor market in many developing countries, carries over to old age and importantly determines the fate of old people.

Timing of Retirement

Regular public and private sector workers withdraw from the labor market much earlier than casual and self-employed workers. More than two thirds of workers holding regular jobs in the public sector in their prime age, and 57% of workers holding jobs in the private sector, completely retired when they were 60 years old. In contrast, only 23 and 18% of workers who were casual workers or the self-employed in their prime age retired when they reached the age of 60, with the gap in retirement status widening with the age of workers (Fig. 6). When reaching age 69, virtually none of the workers who spent their careers in the formal sector are still working full time; in contrast, nearly half (47%) of their counterparts who were casual workers and self-employed are still working full time.Footnote 12 Note that in terms of occupations, the first two categories comprise mostly of white collar workers (officials, managers, clerks, and professionals), in contrast to predominantly blue collar workers comprising the casual and self-employed (mostly skilled agriculture and fishery workers, craft and related workers, and workers in elementary occupations). The observed pattern of retirement is thus contrary to the one found for OECD countries, where blue-collar workers and less-skilled workers are more likely to retire earlier (see OECD 2006).

Retirement status, by the prime-age employment status and age. Source: Own calculations based on World Bank 2006 Sri Lanka Aging Survey. Notes: The prime-age employment status refers to the employment status at age 54; calculations are based on a sample of 1,060 individuals who held full-time jobs at that age. Work related reasons: work stress, travel stress, mandatory retirement, completion of contract, business closed. Health reasons: health reasons or illness, not feeling physically well. Personal reasons: retirement incentives and family obligations

Speed of Retirement

The most prevalent way of withdrawing from the labor market seems to be “overnight,” that is, without engaging in part-time employment. That many workers exit from full-time employment directly to complete retirement is implied by falling LFP and a low share of part-time work. Moreover, according to 2006 SLAS data, of those individuals who held full-time jobs at the age of 54, the vast majority (89%) had retired “overnight,” that is, they did not work part time before retirement, and thus they completed transition to inactivity in a very short time. Interestingly, while the majority of workers across all groups retire overnight, labor market withdrawal via part-time employment is more common for regular workers. In the above sample of individuals, 11–13% of regular public or private sector workers held part-time jobs by the time of the survey as compared to only 6% of casual and self-employed workers. (Note that at the time of the survey, around 40% of casual and self-employed workers still held full-time jobs and very few among the regular workers did so).

Another way of looking at differences at retirement patterns is to observe retirement ages. Figure 7 shows retirement from full-time employment for the selected sample of individuals who held full-time jobs at age 54 as described above. The distribution of retirement age is similar for regular public and private sector workers, with 95% of workers from the first group and 84% from the second group retiring between the ages of 55 and 64 (for public sector workers, there are clear peaks at ages 55 and 60, due to mandatory retirement—not shown in the graph). In contrast, the distribution of retirement age for informal sector workers extends into much older ages, with 16 and 18% of casual and self-employed workers, respectively, retiring between the ages of 76 and 80.

Percentage of retired workers, by the prime-age employment status and age. Source: Own calculations based on World Bank 2006 Sri Lanka Aging Survey. Notes: The prime-age employment status refers to the employment status at age 54; calculations are based on a sample of 1,060 individuals who held full-time jobs at that age. Retirements from full-employment to either complete retirement or part-time work

Industry and Occupational Composition

Changes in industry and occupational composition occur primarily for regular though not for casual and self-employed workers. The proportions of old workers in different industrial sectors remain constant for casual and self-employed workers (see Fig. 8). In contrast, among regular public and private sector workers, the proportion engaged in agriculture increases with age (after age 67, workers who held regular public sector jobs in their prime-age reduce their employment share in agriculture and increase their share in industry). Similarly, the occupational composition for casual and self-employed workers shows little change with time, while among regular public and private sector workers the share of skilled workers increases and the share of professional workers decreases with age (not shown).

Sector of work, by the prime-age employment status and age. Source: Own calculations based on World Bank 2006 Sri Lanka Aging Survey. Note: The prime-age employment status refers to the employment status at age 54; calculations are based on a sample of 1,060 individuals who held full-time jobs at that age

Multinomial Logit Estimates of Transition from Employment

To complement the univariate analysis, we below present the estimates of multinomial logit model of the transition from full-time employment. The results are in line with the ones obtained above, for example, with health status and mandatory retirement provisions being important determinants of retirement. Moreover, the multinomial logit results also confirm that the timing and the modality of the withdrawal from the labor market are strongly influenced by previous working career. Below we describe results in more detail (see the definition of the dependent variable in the model—change of the labour market status of the individual holding full-time job at the age of 54 as compared to his or her status at the age of 61–65—in the “Methodology” section).

The results presented in Table 3 show that work career as proxied by employment status at age 54 is the most important factor determining the work activity of old workers. Among workers who held full-time jobs at the age of 54, all other types of workers compared to regular public sector workers are more likely to work full time from age 61 to 65 (keeping other things equal). These effects are large for workers of all three groups—regular private sector workers, and particularly for casual and self-employed workers: workers from the first group are 40% more likely to work in a full-time job in their early 60s than workers who left regular public sector jobs, and casual and self-employed workers are 66 and 69% more likely, respectively. Interestingly, while casual and self-employed workers are more likely to work full time, they are less likely to work part time as compared to workers who were regular public sector workers at the end of their working career. In other words, while the option of working part time is open to workers retired from regular public sector jobs, this option seems to be less available to casual and self-employed workers.

Other results shed further light on the determinants of retirement. The probability of working in old age decreases progressively with (self-perceived) health problems and the presence of chronic illnesses. Among workers holding full-time jobs at the age of 54, the probability of still working (full- or part-time) for those who reported poor or good health is significantly smaller relative to individuals who reported very good health; for those in poor health, the chances of continuing to work full time are 23% smaller, and for working part time 4% smaller, in comparison to those in very good health. Similarly, the probability of still working in full-time (but not part-time) jobs for individuals who reported a chronic illness is also significantly smaller (11%) in comparison to individuals who did not report a chronic illness.

Results also show that the receipt of pension income is a major factor per se in reducing the labor supply of old people. Other things equal, for workers holding full-time jobs at the age of 54, receiving a pension reduces the probability of still working full time 10 years later by 21% and that of part-time work by 7%. Location also affects the work activity of old people, although the effects are small. Estate sector workers are less likely to work full time between the ages of 61 and 65, relative to urban sector workers, possibly due to the high level of strenuous physical activity associated with estate sector work.

Interestingly, individual characteristics—gender, ethnicity, marital status, being a head of a household—have no significant effect of the studied labor market transitions. We do find, however, that men are more likely than women to make a transition to part-time jobs, as do previously married workers as compared to currently married.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

Our empirical analysis showed that majority of old workers are self-employed or casual workers engaged predominantly in the informal sector in agriculture, manufacturing, and trade. A fair proportion of them, particularly women, work at the bottom of the occupational ladder and only a small proportion as professional workers. Interestingly, most of the old workers that stay active work long hours and have full-time rather than part-time jobs, possibly because the casual and self-employed who opt to work, cannot afford to work part-time. As for the reasons and determinants of retirement, most workers said that they were pushed away from jobs, but while for regular public and private sector workers the main reason was mandatory retirement, for casual and self-employed workers, it was poor health. The receipt of pension is also shown to enable old workers to disengage from the labor market. Moreover, our results show that the majority of regular workers in public and private sector retire early, most of them before they reach 60, and for work-related reasons (including mandatory retirement); in contrast, a large share of self-employed and casual workers continues to work full-time into very old ages, and most of them withdraw from employment for health reasons. These results confirm that labor market duality, the hallmark of labor market in many developing countries, carries over to old age and importantly determines the fate of old people. The paper also showed that in the coming decades, population aging in Sri Lanka is likely to bring a slowdown of labor force growth and after 2030 its contraction.

The reasons for retirement in Sri Lanka differ substantially from those in OECD countries. Similar to workers in OECD countries, a significant share of workers retire upon reaching mandatory retirement age. However, unlike in OECD countries, the single most important reason for withdrawal from the labor market is poor health. It is also likely that a smaller share of workers than in OECD countries is pulled into retirement by family obligations, work stress, travel stress, and work dislike. Moreover, in OECD countries many institutional arrangements exist to entice old workers into retirement or early retirement, ranging from pre-retirement pension schemes to disability and unemployment insurance benefits (OECD 2006). Such arrangements are largely missing in Sri Lanka.

How should Sri Lanka’s labor market and other policies respond? To increase the labor force participation of old workers, the retirement age should be made more flexible and possibilities for part-time work should be increased. One of the hindrances in this regard is the outdated regulation of employment and hours of work embodied in the Shop and Office Act—last amended 25 years ago, the Act does not recognize flexible work schedules nor does it allow for part time work.Footnote 13 More research is needed to determine whether employers’ negative perceptions about the adaptability and productivity of older workers create work militate against employment of old workers—and if so, what should be done about it.

Another area is improving productivity of the labor force. One important task is to improve skills of old workers through investments in life-long learning, the policy that will be more successful with the increase in the expected duration of working career (OECD 1998 also argues that trainability of workers who undergo continued training is less likely to decline). In the context of a developing country, a second important route to make labor more productive is formalization of the economy. On this front, one key task is making the labor market legislation less restrictive so that workers could shift towards better, more productive jobs—and, at the same time, jobs that offer improved social security and pensions. And there is also a third channel of raising productivity: improving the health outcomes of old workers.

The last point points to the importance of improving the choices available to old workers. As documented above, many workers—including a vast majority of informal sector workers—stop working only when they are prevented from doing so by poor health, so improving the health status of old people would significantly relieve financial pressures on them. Old workers’ choices would also significantly improve if they are provided with an independent source of income, hence the need to extend the coverage of old age income support systems.Footnote 14

In a country where extending working lives is key to relieving workers of financial pressures, our finding that poor health—more precisely, according to World Bank (2008), chronic illnesses—is a major cause of withdrawal from the labor market deserves special attention. This finding not only highlights the need to improve health care for old people but also points to the special needs of low socio-economic groups—the groups, as shown by this study, that are most likely to be forced to work long into their old age. Indeed, World Bank (2008) shows that in Sri Lanka, the burden of poor health from untreated non-communicable diseases (NCDs) affects the poor more than the non-poor: the poor have worse access to medical services and thus are less likely than the non-poor to have their NCDs detected and treated. But the need to re-focus health policies to cater better to the needs of old people is clear also from the fact that physical disability rates among the old people in Sri Lanka in the past two decades have increased, in contrast to many other health outcomes.

Notes

Sri Lanka is a lower middle-income country (its GNP per capita in 2008 was US$2,014). Its economy has been steadily growing over the last few decades, with the average growth rate for the decade ending in 2007 being 5.0%. The share of agricultural employment has been steadily shrinking, reaching 32% in 2006 (Arunatilake and Jayawardena 2008); in contrast, the share of informal workers has been remarkably stable, with two out of three workers holding informal jobs in 2006.

While modernization is affecting Asian societies in different ways, there is evidence of declining co-residence of old people with their children in developed Asian countries—Japan and South Korea (see Hermalin 1995; Knodel and Ofstedal 2002; Kim 1999), and also of a sharp decline in expected co-residence in Taiwan (Hermalin and Yang 2004). But there are exceptions, for example Vietnam, where family support systems seem remarkably stubborn (we are grateful to an anonymous referee for pointing this out).

The notion of unemployment differs substantially among developing and developed countries, and so using the standard, ILO definition for the latter may well classify some unemployed as employed, thus reducing the measured unemployment rate. Such workers may be “underemployed,” that is, work less hours than they would like or work in low productivity jobs, but they are poor and they cannot afford to be without a job.

For more details about the survey, see World Bank (2008).

Unpaid family workers were not included in the analysis, due to small (20 observations) sample size.

For example, a temporary worker working for the formal sector is considered to be an informal sector worker.

Elementary occupations are those that come under major group 9 of International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO), these include occupations such as street vendors, domestic helpers, and caretakers.

The question on retirement status was not relevant for 66% of old females. This arises from the fact that many females do not participate in market based economic activities in younger ages. According to DCS, Labor Force Survey data, 60% of females 60 to 64 years old are unavailable work, because they are engaged in household activities. Although this percentage decreases for old age cohorts even at 80 plus years of age, 6% of old females state that they are not available for work due to household work.

Only pay of employees are discussed.

Note that these profiles are derived from cross-section data and may not necessarily reflect life-cycle profiles (that is, age–wage profiles of the same workers traced through time), because these profiles may be heavily influenced by the selection of workers: other things equal, high-paid workers are more likely to withdraw from the labor market later in their career than low-paid workers. The increase of relative wages for workers in their early 60s compared with workers in their late 50s in the private sector, thus reflects two opposing effects: the selection effect (that is, a higher likelihood that better paid workers stay employed) as well as the negative effect of age on wages of life-cycle wage profile, with the former prevailing (that is, better-paid workers self-select and continue working while lower-paid workers transfer to inactivity).

As described, for example, by OECD (2006), pull factors are associated primarily with financial incentives provided by pension schemes and family obligations such as helping with childcare of grand children, and push factors with firm and personal circumstances that restrict job opportunities of old workers (such as perceptions about the capacities of old workers and mandated benefits or increases in wages associated with age or work experience).

A log rank test showed that the survival curves for the four sectors of employment—that is, regular public sector workers, regular private sector workers, casual workers and self-employed—were statistically different.

Interestingly, Sri Lanka’s wage-setting mechanism appears not to be an obstacle for employment of old people. As shown above, the age–wage profile for the private sector reaches its peak for the 30–34 age group, slowly decreases thereafter, and experiences a sharp drop after the age of 60. While this drop may reflect the selection process that is not accounted for the age-wage profiles based on cross-section data, the magnitude of the drop of wages of old workers nonetheless suggests that the level of wages of old workers is not a disincentive to hire or retain old workers in Sri Lanka.

World Bank (2008) points to the weaknesses of the current schemes for informal workers in Sri Lanka and lays out an alternative strategy to expanding social security to informal sector workers.

References

Arunatilake, N., & Jayawardena, P. (2008). Labor market trends and outcomes in Sri Lanka. Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka, processed.

Hermalin, A. I. (1995). Ageing in Asia: Setting the research foundation. Asia-Pacific research reports, no. 4. East-West Center, program on population.

Hermalin, A. I. (2002). The well-being of the old persons in Asia: A four-country comparative study. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hermalin, A. I., & Yang, L. S. (2004). Levels of support from children in Taiwan: expectations versus reality, 1965–99. Population and Development Review, 30(3), 417–448.

Kim, I. K. (1999). Population ageing in Korea: social problems and solutions. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 26(1), 107–123.

Knodel, J., & Ofstedal, M. B. (2002). Patterns and determinants of living arrangements. In A. I. Hermalin (Ed), The well-being of the old persons in Asia. University of Michigan Press.

MacKellar, F. L. (2000). The predicament of population aging: a review essay. Population and Development Review, 26(2), 365–397.

OECD. (1998). OECD employment outlook. Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2005). Health at glance: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2006). Live longer, work longer. Paris: OECD.

Vodopivec, M., & Arunatilake, N. (2008). Population ageing and the labor market: The case of Sri Lanka. IZA discussion paper no. 3456, April 2008.

World Bank (2007). Sri Lanka: Strengthening social protection. World Bank: Human Development Unit, South Asia Region, Report No. 38197-LK.

World Bank (2008). Sri Lanka: Addressing the needs of an aging population. World Bank: Human Development Unit, South Asia Region, Report No. 43396-LK.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Gordon Betcherman, Ralitza Dimova, Ravi Peiris, Ravi Rannan-Eliya, Shyamali Ranaraja, Mansoora Rashid, Nimnath Withanachchi, and especially two anonymous referees for their useful comments, and Priyanka Jayawardena for excellent research assistance. We owe a special gratitude to Mr. A.G.W. Nanayakkara, former Director General, and Mr. Yasantha Fernando, Director, Sample Service, the Department of Census and Statistics, for providing the sampling frame for the aging survey, and to ACNielsen Lanka (Pvt.) Limited for the careful administration of the survey. Partial funding under the TFESSD trust fund grant is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vodopivec, M., Arunatilake, N. Population Aging and Labour Market Participation of Old Workers in Sri Lanka. Population Ageing 4, 141–163 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-011-9045-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-011-9045-5