Abstract

Understanding the drivers of the floating population’s settlement intentions in Chinese cities is vital to guide evidence-based urban economic development policies. Prior studies have been inclined to use static cross-sectional analysis providing insights into the relative importance of the factors that drive the distribution of urban settlement intentions. Yet, little has adopted longitudinal data approaches to delve into their spatial-temporal patterns and changes in determinants. This study applies China Migrants Dynamic Survey data of 2014–2017 to examine the spatial distribution of urban settlement intentions of floating migrants and their determinants over time. It reveals a persistent and spatially differentiated pattern of urban settlement intentions, where floating migrants relocating to some small and medium-sized cities in several northern parts of China are more willing to settle down. Results from a two-way fixed-effects panel model indicate that both internal motivations and external constraints are closely related to the settlement decision process of floating migrants. The number of family members living together, marriage rate, duration of stay, insurance coverage, the average wage of employees, the proportion of employees in the education industry, and per capita fiscal expenditure positively correlate with settlement intentions, while the proportion of interprovincial floating migrants and urban employment rate have a negative relationship with settlement intentions. Our results further suggest that internal drivers are a prerequisite for external drivers to play a role in driving the urban settlement of migrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interregional population migration exerts enormous impacts on regional economic and social development (Fan 2005; Liu and Gu 2019). In China, the household registration (hukou) system has restricted the free movement of people between regions since the 1950s (Chan 2009). According to the status of the hukou possession for migrants, scholars have divided China’s migrants into two types: permanent migrants and temporary (floating) migrants (Chan et al. 1999; Fan 2002; Liu and Xu 2017). Floating migrants represent those who have not obtained local urban hukou in destination cities despite staying for a stipulated period (e.g., 6 months), while permanent migrants refer to those who have stayed in destination places and have been granted with urban hukou (Gu et al. 2020a). Realizing that the hukou restrictions of regional migration had hindered regional economic development and prevented the progress of urbanization, the Chinese government has promoted the reform of the hukou system. Since the 1980s, limitations on interregional migration has gradually diminished, and China has witnessed a surge in the scale of rural-urban migration, providing sufficient labor force to industries in those developed regions, and thus, in turn, stimulating local economic development (Chan 2019; Gu et al. 2020a). In 2014, the Chinese government set forth “the National New Urbanization Plan (2014–2020)”, enforcing further loose of hukou restrictions, promoting China’s urbanization, and guiding more floating migrants to settle in cities (especially those small and medium-sized cities). The later formulated policy “the Key Tasks of New-Type Urbanization Construction” in 2019 claimed that the settlement restrictions for floating migrants in small and medium-sized cities should be fully liberalized shortly.

Local hukou of the city guarantees citizens’ social rights and access to public services, and it is also regarded as a representation of social status for citizens (Chan 2019; Wei and Su 2013). However, in most cases, floating migrants are not fully covered by the rights and benefits bound to local hukou. In contemporary China, the increasing size of the floating population in cities has caused a state of semi-urbanization, which leads to some problematic social issues, such as the over-occupation of urban public service resources and the crowding in the local job market (Wei and Su 2013). Despite these social issues, China has been still witnessing massive volumes of the floating population in cities. By the end of 2017, the size of the floating migrants had reached 245 million, accounting for 17.6% of the total population (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2018). However, China has been slowing down its pace in urbanization in recent years, reflecting the fact that a considerable number of migrants have returned home or migrated to other cities rather than settled in destination cities. With this regard, the research on the characteristics and drivers of the settlement of floating migrants in cities is of vital practical significance in China during the transition period.

In China, due to limited data availability, indicators measuring the migration tendency of floating migrants at the city level used to be relatively lacking. Since 2009, the access to some survey data of the floating population has enabled the research on related issues of floating migrants’ migration behaviors. Numerous studies have been conducted on the urban settlement intention of floating migrants (Gu et al. 2018; Huang et al. 2018a; Lin and Zhu 2016; Tan et al. 2017; Yue et al. 2010; Zhu 2007; Zhu and Chen 2010). Although the settlement intention cannot fully represent the final migration decision (Gu et al. 2020a), it measures possible settlement tendencies of migrants, which are determined by both external constraints of the city and subjective preferences of migrants (Gu et al. 2018; Lin and Zhu 2016; Liu et al. 2018). Extant studies have tended to adopt a static cross-sectional approach providing novel insights into how the drivers shape the distribution pattern of the urban settlement of the floating population. Yet, changes in the influence of the determinants on the shifts in the spatial dynamics of the settlement intention over time have remained largely underexplored. Understanding these changes is of great significance in guiding evidence-based policies and regulations on the management of the urban floating population.

Drawing on China Migrants Dynamic Survey (CMDS) data, the present paper contributes to previous studies by using four-year city-level data of the urban settlement intention of floating migrants from 2014 to 2017. Several spatial data analyses are applied to elaborate on the spatial-temporal patterns of settlement intentions, and a fixed-effects panel model is employed to examine how these factors, including internal and external drivers, affect the spatial distribution of urban settlement intentions. The longitudinal data analysis widens our knowledge of the dynamics in the changes of settlement intentions over time and thus providing novel references for the policymakers.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on migrants’ settlement intentions. Section 3 presents the conceptual framework, data, and model specification. Section 4 and Section 5 describe the results from spatial analysis and econometric models. Section 6 further discusses the linkages between various determinants and the spatial distribution of settlement intentions and provides some policy recommendations. Section 7 summarizes the main findings of the paper.

Internal Motivations, External Constraints, and Urban Settlement Intentions

Interregional migration is a complex decision-making process affected by multiple factors (Stillwell et al. 2018). Classical theories have explained the motivations of migrants from the perspective of economic factors, such as the wage disparity (Todaro 1969), relocation of industries (Krugman, 1991), and family utility maximization (Stark and Bloom 1985). Another group of scholars, however, have given their attention to the supply of public goods and urban natural amenities (Glaeser et al. 2001; Graves 1976; Tiebout 1956). Graves (1976) argued that the city’s wage income and the city’s amenities were in a complementary relationship, with the sum as the urban rent. Glaeser et al. (2001) further pointed out that urban amenities, including urban consumption levels, transportation, physical facilities, and public services, were positively related to urban immigration. Previous theories and empirical studies of interregional migration in western countries have provided references for the migration research in China on the role of economic factors, urban amenities, and institutional factors in shaping the migration pattern (Gu et al. 2019a; Liu and Shen 2014, 2017; Liu and Xu 2017; Liu and Gu 2019; Xiang et al. 2018; Xu and Ouyang 2018).

The unique hukou system in China has led to massive volumes of the floating population in cities, which has drawn much attention from policymakers, national and international firms, media, and academia (Gu et al. 2020a). Since 2009, supported by national or regional survey data of the floating population, a burgeoning body of literature has been conducted on depicting the subjective intentions of migration for floating migrants, including settlement intentions, hukou transfer intentions, and return intentions (Fan 2011; Gu et al. 2018, 2019a, b, 2020a, b; Huang et al. 2018a, b, 2020; Liu et al. 2017; Tan et al. 2017; Wei 2013; Zhu 2007; Zhu and Chen 2010). Among existing studies, the settlement intention of floating migrants in cities has received widespread concerns. It is found that the internal motivations of the floating population are significantly associated with their settlement intentions in cities (Zhu 2007; Zhu and Chen 2010). Regarding individual and family factors of migrants, scholars discovered that younger and married migrants had a higher intention to settle in the city, so were those with more family members living together (Huang et al. 2020; Zhu 2007; Zhu and Chen 2010). Economic conditions and migration factors are also found to have an impact on settlement intentions (Chen and Liu 2016). In general, migrants with a lower income level, a longer migration distance and shorter duration of staying are less willing to settle down. In addition, social factors including employment status, insurance coverage, etc. play a crucial part in the decision-making of migrants (Cao et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2018a; Yue et al. 2010). Researchers found that those with higher employment status, covered with insurance of employees or better integrated into the destination city were more possible to settle down.

Apart from internal drivers, external constraints of the destination city are also significantly related to the settlement intention of migrants, although these factors have received limited attention in earlier research. Lin and Zhu (2016) and Gu et al. (2018) examined the influence of characteristics of the destination city on settlement intentions. Prior studies have also focused on the impact of urban factors on the hukou transfer intention and return intention of urban floating migrants in China (Gu et al. 2019b, 2020a). Research has confirmed that urban economic factors predominantly affect the settlement intentions of floating migrants (Huang et al. 2018b). High wage levels, optimized industrial structures, and low unemployment rates of the city are found to enhance the floating population’s settlement intentions (Gu et al. 2020b; Liu et al. 2018). However, the existing literature has not arrived consistent conclusions on the impact of urban amenities (public services, air pollution, etc.). This may be related to the situation that urban residents’ right to enjoy public services is largely bound to their hukou status (Wei and Su 2013).

Furthermore, the influencing factors of floating migrants’ settlement intentions have differential characteristics in various regions of China (Gu et al. 2020b; Lin and Zhu 2016; Liu et al. 2018; Wei 2013). Using a Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) method, Gu et al. (2020b) verified a spatially-varying effect of the urban factors on floating migrants’ settlement intentions. Besides, it is found that the factors that affect settlement intentions are mutually influential and interrelated among neighboring regions, thus the settlement intentions may possess strong spatial autocorrelation across space (Gu et al. 2018). Based on the CMDS data, Gu et al. (2018) found strong and positive spatial autocorrelation in the spatial distribution of settlement intentions at the city level, and the spatial autocorrelation was mainly caused by unobservable factors (e.g., cross-regional policies). To sum up, research has partially demonstrated the characteristics of spatial heterogeneity and spatial autocorrelation in the distribution pattern of settlement intentions.

Several studies have compared the influence between internal and external drivers on the migration intentions of floating migrants. Gu et al. (2018, 2020b) suggested that internal motivations are more influential than external constraints in the choice of the urban settlement of migrants. Other studies, however, argued that the urban settlement intention of the floating population is affected simultaneously by both individual factors and characteristics of the city (Lin and Zhu 2016; Liu et al. 2018). Overall, an increasing body of literature on the determinants of the urban settlement intention of migrants have begun to take into account the impact of the destination city. Yet, due to the data limitation, existing studies fail to model the determinants of settlement intentions using longitudinal city-level data; thus, their conclusions from cross-sectional analysis are sometimes less rigor and robust. The study attempts to make up for existing research by employing a four-year longitudinal data analysis.

Conceptual Framework, Data, and Model Specification

Conceptual Framework

This paper assumes that urban floating migrants’ migration decisions depend on their migration utilities. The settlement intention in a city is defined as the proportion of floating migrants with settlement intentions in the city, which reflects the attractiveness of the city to floating migrants. The settlement intention of floating migrants is mainly determined by the internal motivations of the individuals and families, as well as the external constraints of the city (Lin and Zhu 2016; Liu et al. 2018). Following previous literature (Gu et al. 2018, 2020b; Lin and Zhu 2016; Liu et al. 2018), the twofold factors can be summarized explicitly into six categories: individual and family factors (I), migration characteristics (M), socioeconomic factors (S), urban economic factors (E), urban public service supply (P), and urban natural amenities (A). Then, the utility function for migrants in a particular city i at time t is expressed as: Uit = U(Iit, Mit, Sit, Eit, Pit, Ait). This framework also needs to controls time fixed-effects (T) and individual fixed-effects (C) to avoid the problem of potential missing variables. Given a particular city i and any other city j, the prerequisite for urban floating migrants to settle in the city i at time t is Uit > Ujt for ∀i ≠ j. This framework implies the assumption that internal motivations and external constraints jointly affect migrants’ urban settlement intentions.

Research Data

The research units in the study are prefecture-level administrative units (hereafter, cities) in China, including prefecture-level cities, autonomous prefectures, and municipalities. Due to data availability, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan are excluded. Cities are usually the primary formulation and implementation units of floating population and regional development policies, and thus floating migrants’ settlement intentions are inevitably affected by external constraints of destination cities (Gu et al. 2018). Considering the changes in China’s administrative divisions and data sources over the years, the number of selected cities in our final dataset in 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017 are 285, 297, 298, and 306, respectively.

Data used in this study are derived from the CMDS of 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017, conducted by the National Health Commission of China. In CMDS datasets, a multistage stratified random sampling method with probability proportional to size is adopted to extract sampling points from target areas with a high concentration of floating population in 31 provincial units in China (Gu et al. 2020c). Respondents of the CMDS are migrants over 15 years old who have lived in their destinations for more than a month without being granted local urban hukou. Whether a migrant has the willingness to settle in the city depends on the answer to the question “Do you intend to stay here for five years or more in the future?”. Migrants who answered “Yes” are defined as those who have settlement intentions, while those who answered “No” or “Not sure” are defined as those without the intention of urban settlement. The dependent variable used by us is the proportion of migrants who have settlement intentions in the total migrants in the city (Gu et al. 2018; Liu and Zhu 2016; Liu et al. 2018). By doing so, original micro-level data are aggregated to the city-level.

The econometric analysis in our paper considers regional socioeconomic factors selected from the China City Statistical Yearbook of 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017, which provide variables of Chinese cities in 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016, respectively. The independent variables of the city lag the dependent variable by 1 year, which conduces to mitigate the endogeneity of reverse causality to some degree (Gu et al. 2019c; Zhou et al. 2019). Variables revealing characteristics of the floating population are derived from CMDS datasets from 2014 to 2017, where micro-level variables are aggregated to the city-level by average computation. The description and descriptive statistics of the variables are listed in Table 1.

Model Specification

Our model specification follows the logic of the conceptual framework. The individual and family factors include the average age (Age), marriage rate (Marry), and the number of family members living together (Family). Some previous studies show a negative relationship between age and settlement intentions (Zhu 2007; Zhu and Chen 2010). According to social network theory, family as a guarantee of individual survival shares the risks of employment and income for the individual, and thus we expect the effects of marriage rate and the number of family members living together are positively correlated with migrants’ settlement intentions.

The migration characteristics include the proportion of floating migrants across provinces (Dist) and the average duration of stay (Stay). Longer migration distance brings evident cultural differences and weaker senses of belonging, yet a longer stay duration may promote the social integration of migrants (Freeman 2000). Therefore, it is expected that cross-province migration weakens the settlement intention, but the duration of stay positively correlates with the settlement intention. Socioeconomic factors include the coverage of basic medical insurance of urban floating migrants (Insure) and the ratio of the annual family income of floating migrants to the average annual wage of urban employees (Income), and we expect positive effects of both variables.

Urban economic factors are characterized by the urban unemployment rate (Unemp), the average annual wage of urban employees (Wage),Footnote 1 and the proportion of tertiary industry output (Tindus). Since one of the motivations for floating migrants is to obtain more employment opportunities and higher economic incomes in the city, we expect the average annual wage of employees is positively related to the settlement intention, while the effect of the unemployment rate is the opposite. We also expect the estimates of the proportion of tertiary industry output to be positive.

The following three variables measure public service supply: per capita government annual expenditure on public services (Exp), proportion of employees in education-related industries (Edu), and per capita road area in the city (Road). In general, better public services provide more convenience for urban floating migrants; thus, the improvement of the supply of public services in a city increases migrants’ willingness to stay. However, the hukou restrictions may prevent migrants from acquiring public services, thus, the expected effects of the public service variables are not very clear.

Not only that, this paper considers the impacts of urban natural amenities on the settlement intention. They are measured by urban sulfur dioxide emissions (Air) and the urban greening rate in the built-up area (Green). The effect of the former is expected to be positive, while that of the latter is negative.

Considering the effects of external and internal drivers, we build a two-way fixed-effects panel model to investigate the factors affecting the settlement intention of floating migrants, with time fixed effects and individual fixed effects controlled. The model specification is as follows:

where yi, t is the settlement intention of floating migrants in the city i at time t. Ii, t, Mi, t, Si, t, Ei, t, Pi, t, and Ai, t represent individual and family factors, migration characteristics, socioeconomic factors, urban economic factors, urban public service supply, and urban natural amenities of the city i at time t, with α1…α6 as corresponding coefficients. α0 denotes the constant term. Tt and Ci refer to the time fixed and individual fixed effects. εit is the error term.

Settlement Intention of Floating Migrants in Chinese Cities

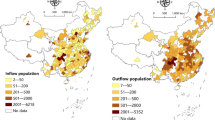

This section investigates spatial-temporal patterns of floating migrants’ settlement intentions in Chinese cities. As shown in Fig. 1, we map the settlement intention of China’s urban floating migrants from 2014 to 2017 in GIS software and classified the values by natural breaks criteria. The result illustrates a persistent pattern of high spatial heterogeneity of settlement intentions during the 4 years. Migrants in northern cities of China had higher inclinations to settle down, while those in southern cities had lower settlement intentions. Cities with higher settlement intentions were located primarily in the Shandong Peninsula, Northeast China, and Inner Mongolia, while southeastern cities had lower settlement intentions. It further indicates that cities with higher settlement intentions were not limited to those attractive megacities (e.g., Beijing and Shanghai) and second-tier emerging cities (e.g., Qingdao). However, quite a few small and medium-sized cities in the inland or remote region also appealed to a large percentage of floating migrants. This finding is consistent with the results of Liu et al. (2018). Not only less-competitive labor markets in these small and medium-sized cities but the formulation of favorable settlement policies have attracted more floating migrants in recent years.

Measures of inequality are employed to describe the degree of spatial unevenness in the distribution of settlement intentions.Footnote 2 As reported in Table 2, results from the Gini index and coefficient of variation suggest that the degree of inequality of the spatial patterns of settlement intentions was relatively low between 2014 and 2017. Floating migrants had propensities to settle in a larger quantity of cities rather than to concentrate in a small set of developed cities, which is in part related to strict settlement policies in large cities in China. Besides, we examine positive spatial autocorrelation in the spatial patterns of settlement intentions. Results from the Moran’s IFootnote 3 reveal significant and positive spatial autocorrelation in the spatial patterns of settlement intentions during the 4 years, indicating that the settlement intention in a particular city was closely associated with that of the surrounding cities. This is partly on account of positive spatial dependence among factors influencing settlement intentions (e.g., agglomeration economies, cross-city social network, and mutually responsive regional development policies).

Driving Forces of the Settlement Intention of Floating Migrants

Model Procession

This section begins with discussing the model processing in our study. Our independent variables are divided into two categories: external constraints and internal motivations. The standard error in our model is corrected by White heteroscedasticity to make the result more robust. Hausman test is conducted prior to the empirical analysis for the choice between a fixed-effects model and a random-effects model. Hausman test result shows that chi2 = 86.62, rejecting the null hypothesis that “independent variables are not related to random effects”; thus, the fixed-effects model is more appropriate to use in our case. Our regression strategy is to add independent variables of various aspects by step. Individual variables firstly enter the model (Model 1), followed by migration characteristic variables (Model 2), socioeconomic variables (Model 3), urban economic variables (Model 4), public service variables (Model 5), and urban natural amenity variables (Model 6). To further compare the effects of external and internal drivers, we construct Model 7, which only incorporates variables of the city. By using this regression strategy, we shed light on the effects of different influencing factors and test the robustness of the results (Table 3).

Results

Results from Model 1 indicate a negative relationship between the average age of migrants (Age) and their urban settlement intentions, but the coefficient is not significant. The estimates of the marriage rate (Marry) and the number of family members living together (Family) are significantly positive, which confirms the role of the family factors on floating migrants’ settlement choices (Haug 2008). Stronger family nexus in destination cities reduces the risk of social integration and entering the local labor market for new migrants (Fan, 2011; Huang 2018a).

Model 2 incorporates migration factors. Results show that the proportion of interprovincial migrants (Dist) has a significantly negative relationship with settlement intentions, while the duration of stay (Stay) negatively correlates with settlement intentions. Interprovincial migration usually has a long-distance movement compared with intra-province migration, which brings differences in living habits and cultures between origins and destinations (Fan 2005). A closer migration distance implies similar socio-cultural conditions for migrants, which in turn increases their settlement intentions (Huang et al. 2018a). A long duration of staying also reflects better social integration for migrants, which enhances their settlement intentions (Yang et al. 2020). It also illustrates an association relationship between average age (Age) and settlement intentions, whereas this relationship is not very robust across the models.

Socioeconomic factors are added in Model 3. The results indicate that a city with a higher percentage of floating migrants covered with employee medical insurance has a higher settlement intention. This finding confirms the effect of the social security system on migrants’ settlement intentions, which is in line with some previous empirical studies (e.g., Gu et al. 2020b). Also, we discover that there is no relationship between family income to urban wage ratio (Income) and their settlement intentions, which is against our expectations. A possible reason is that a large percentage of floating migrants move away from their hometowns to cities to earn money and improve their total family incomes by remittances. Once they achieve their income expectations, they will return to their hometowns (Dustmann 2003).

Model 4 considers the effects of the urban economy. There is a significant negative relationship between the urban unemployment rate (Unemp) and settlement intentions, while the estimate of urban employees’ average wage (Wage) is positive. A low unemployment rate reflects better employment security and a more stable job market in the city, which increases migrants’ settlement intentions. However, not as expected, it is found that the estimate of the proportion of output value of the tertiary industry in a city (Tindus) is insignificant, implying that the industrial structure has no relationship with settlement intentions.

We further put variables of urban public services into the model. The results only confirm a significant relationship between the proportion of employees in the education industry (Edu) and the settlement intention in a city, which illustrates the role of a city’s basic education resources. However, the coefficients of per capita road area in a city (Road) and per capita fiscal expenditure (Exp) are insignificant. This is partly because the public services in destination cities do not fully occupy floating migrants without local hukou.

Results from Model 6 reveals that there is an insignificant relationship between urban natural amenities and settlement intentions of floating migrants. Estimates of the Sulfur dioxide emissions of a city (Air) and the greening coverage rate in built-up areas (Green) fail to pass the significance test. The findings are not consistent with previous studies arguing that the improvement of urban amenities can appeal to more migrants (McGranahan 1999; Rappaport 2009). However, it is found that with the urban natural factors considered, the estimate of Exp becomes significant.

In Model 6, all variables are taken into consideration, and thus we can make a quantitative description of the influences of various factors. Generally speaking, floating migrants’ settlement intentions are affected by both internal motivations (family connection, social integration, and social security) and external constraints (urban economy, education, and fiscal expenditure). Among the internal drivers, the family nexus and social integration of migrants significantly correlate with their settlement intentions. One more family member living together increases the settlement intention by 7.21%, and one more year of staying in destination cities promotes the settlement intention by 1.075%. As for the impact of medical insurance coverage, it is found that a 1% increase in the coverage rate of employee medical insurance increases the settlement intention by 0.198%. When it comes to external drivers, our results show the role of the urban economy. To be specific, a 1% increase in the average annual wage of urban employees triggers a 16.56% increase in the settlement intention of the city, while a 1% increase in the unemployment rate decreases the settlement intentions by 0.392%. The proportion of employees in education industries and per capita fiscal expenditure also play a role. Their coefficients reach 0.478 and 6.255, respectively.

Furthermore, we construct Model 7, which only incorporates the external factors, to investigate the relationship of external constraints and the settlement intention of floating migrants. By comparing the results between Model 7 and Model 3, we find that when external constraints are not controlled, the variables of internal drivers are still significant, whereas most of the variables of external drivers are insignificant when internal motivations are not included in the model. This implies that internal motivations are a prerequisite for external constraints to make a difference. This finding also echoes the conclusion in some previous literature arguing that urban factors play an less important role in China’s urban floating population’s settlement intention than individual characteristics (Gu et al. 2020b) since benefits brought by the city may matter more for permanent residents who are granted urban hukou than the floating population.

Discussion

Our results have indicated a spatially differentiated pattern of floating migrants’ settlement intentions during 2014–2017 where some small and medium-sized cities in several northern parts of China have higher settlement intentions. Interestingly, some cities with high settlement intentions are not limited to those megacities such as Beijing and Shanghai. The interpretation of this distribution pattern has a close relationship with the findings from the econometric models. Internal drivers are a prerequisite for external drivers in the decision-making of the choice of urban settlement for migrants. Family nexus, degree of social integration, and social security system coverage of the floating population are usually not affected by factors of destination cities. Yet, they may play a more crucial role in shaping the pattern of urban settlement intentions than external drivers. For example, cities in Northeast China may share similar cultural practices, thus lowers the cost of social integration of migrants originating from northeastern cities and enhances their willingness to settle down. Our finding of the distribution pattern of urban settlement intention is analogous with that of Liu et al. (2018), but we provide evidence for the interpretation of the spatial pattern from the differences between internal and external drivers.

However, our results do not deny the role of urban factors. Yet, it is found that the economic conditions and public services in destination cities are closely associated with settlement intentions. In response to the future tendency of urban settlement for floating population, those small and medium-sized cities that have higher settlement intentions are suggested to consummate the employment market for floating migrants and provide sufficient employment and housing securities. Also, these cities need to develop their economies further, especially raise the income level of urban residents. For cities with a lower attraction to floating migrants, to promote their urbanization rates, they are suggested to focus more on the characteristics of the local floating population and strive to establish a closer family and social connections for floating migrants. In addition, local governments should provide better social security for these non-local migrants and ensure that they have equal rights to urban public services.

Conclusions

Due to data availability, previous literature primarily gives limited attention to the spatial pattern and determinants of floating migrants’ settlement intentions in Chinese cities through longitudinal data analysis. The present study contributes to previous research by employing the city-level four-year panel data to assess the drivers of urban settlement of the floating population in 2014–2017. Our results have indicated a persistent and spatially differentiated pattern of urban settlement intentions of migrants where some small and medium-sized cities in several northern parts of China have higher values. There is positive spatial autocorrelation in the spatial patterns of settlement intentions, but the degree of inequality is relatively low.

Results from the fixed-effects panel model have indicated that the settlement intention of floating migrants is driven simultaneously by both internal motivations (family nexus, social integration degree, and social security) and external constraints (urban economy, education level, and fiscal expenditure). Among internal drivers, marriage rate, number of family members living together, duration of stay, and coverage of basic medical insurance are positively associated with floating migrants’ settlement intentions, while the proportion of interprovincial floating migrants has a negative relationship with the settlement intentions. Among external drivers, the average annual wage of urban employees, per capital fiscal expenditure, and the proportion of employees in the education industry are positively related to floating migrants’ settlement intentions, while the urban employment rate negatively correlates with urban settlement intentions. Further, we compare the effects of internal and external drivers. It reveals that internal motivations are a prerequisite for external constraints to play a role.

Notes

Since prices level have changed over years, we divide the average annual wage of urban employees by the CPI of the corresponding year.

We apply the Gini index (GI) and Coefficient of variation (CV) to measure the spatial inequality of settlement intentions at the city level. The GI is computed as: \( GI=\frac{1}{2{n}^2\overline{x}}\sum \limits_{i=1}^n\sum \limits_{j=1}^n\left|{x}_i-{x}_j\right| \), where n refers to the number of cities, \( \overline{x} \) is the average of settlement intentions, xi, xj represent the values of settlement intentions in any two cities. The CV is expressed as: \( CV=\frac{1}{\overline{x}}\sqrt{\frac{\sum \limits_{i=1}^n{\left({x}_i-\overline{x}\right)}^2}{n-1}} \), where xi is the value of settlement intention in a city i.

The Moran’s I (MI) is widely used in detecting spatial autocorrelation in the data. It be expressed as: \( MI=\frac{X^{\prime}\boldsymbol{W}X}{X^{\prime }X} \), where X denotes the vector settlement intentions of cities, W represents the distance-based spatial weight matrix.

References

Chan, K. W., Liu, T., & Yang, Y. (1999). Hukou and non-hukou migrations in China: Comparisons and contrasts. International Journal of Population Geography, 5(6), 425–448.

Chan, K. W. (2009). The Chinese hukou system at 50. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 50(2), 197–221.

Chan, K. W. (2019). China’s hukou system at 60: Continuity and reform. Handbook on Urban Development in China, 59–79.

Cao, G., Li, M., Ma, Y., & Tao, R. (2015). Self-employment and intention of permanent urban settlement: Evidence from a survey of migrants in China’s four major urbanising areas. Urban Studies, 52(4), 639–664.

Chen, S., & Liu, Z. (2016). What determines the settlement intention of rural migrants in China? Economic incentives versus sociocultural conditions. Habitat International, 58, 42–50.

Dustmann, C. (2003). Return migration, wage differentials, and the optimal migration duration. European Economic Review, 47(2), 353–369.

Fan, C. C. (2002). The elite, the natives, and the outsiders: Migration and labor market segmentation in urban China. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 92(1), 103–124.

Fan, C. C. (2005). Modeling interprovincial migration in China, 1985-2000. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 46(3), 165–184.

Fan, C. C. (2011). Settlement intention and split households: Findings from a survey of migrants in Beijing’s urban villages. The China Review, 11–41.

Freeman, L. C. (2000). Visualizing social networks. Journal of Social Structure, 1(1), 4.

Glaeser, E. L., Kolko, J., & Saiz, A. (2001). Consumer city. Journal of Economic Geography, 1(1), 27–50.

Graves, P. E. (1976). A reexamination of migration, economic opportunity, and the quality of life. Journal of Regional Science, 16(1), 107–112.

Gu, H., Xiao, F., Shen, T., & Liu, Z. (2018). Spatial difference and influencing factors of settlement intention of urban floating population in China:Evidence from the 2015 National Migrant Population Dynamic Monitoring Survey. Economic Geography, 38(11), 22–29 (in Chinese).

Gu, H., Liu, Z., Shen, T., & Meng, X. (2019a). Modelling interprovincial migration in China from 1995 to 2015 based on an eigenvector spatial filtering negative binomial model. Population, Space and Place, 25(8), e2253. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2253.

Gu, H., Qin, X., & Shen, T. (2019b). Spatial variation of migrant population's return intention and its determinants in China's prefecture and provincial level cities. Geographical Research, 38(8), 1877–1890 (in Chinese).

Gu, H., Meng, X., Shen, T., & Wen, L. (2019c). China’s highly educated talents in 2015: Patterns, determinants and spatial spillover effects. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 1–18.

Gu, H., Liu, Z., & Shen, T. (2020a). Spatial pattern and determinants of migrant workers' interprovincial hukou transfer intention in China: Evidence from a National Migrant Population Dynamic Monitoring Survey in 2016. Population, Space and Place, 26(2), e2250. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2250.

Gu, H., Meng, X., Shen, T., & Cui, N. (2020b). Spatial variation of the determinants of China’s urban floating population's settlement intention. Acta Geographica Sinica, 75(2), 240–254 (in Chinese).

Gu, H., Li, Q., & Shen, T. (2020c). Spatial difference and influencing factors of floating Population’s settlement intention in the three provinces of Northeast China. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 40(2), 261–269 (in Chinese).

Haug, S. (2008). Migration networks and migration decision-making. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34(4), 585–605.

Huang, X., Liu, Y., Xue, D., Li, Z., & Shi, Z. (2018a). The effects of social ties on rural-urban migrants' intention to settle in cities in China. Cities, 83, 203–212.

Huang, Y., Guo, F., & Cheng, Z. (2018b). Market mechanisms and migrant settlement intentions in urban China. Asian Population Studies, 14(1), 22–42.

Huang, X., He, D., Liu, Y., Xie, S., Wang, R., & Shi, Z. (2020). The effects of health on the settlement intention of rural–urban migrants: Evidence from eight Chinese cities. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-020-09342-7.

Lin, L., & Zhu, Y. (2016). Spatial variation and its determinants of migrants' hukou transfer intention of China's prefecture-and provincial-level cities: Evidence from the 2012 national migrant population dynamic monitoring survey. Acta Geographica Sinica, 71(10), 1696–1709 (in Chinese).

Liu, Y., Deng, W., & Song, X. (2018). Influence factor analysis of migrants' settlement intention: Considering the characteristic of city. Applied Geography, 96, 130–140.

Liu, Y., & Shen, J. (2017). Modelling skilled and less-skilled interregional migrations in China, 2000–2005. Population, Space and Place, 23(4), e2027.

Liu, Y., & Shen, J. (2014). Jobs or amenities? Location choices of interprovincial skilled migrants in China, 2000–2005. Population, Space and Place, 20(7), 592–605.

Liu, Y., & Xu, W. (2017). Destination choices of permanent and temporary migrants in China, 1985–2005. Population, Space and Place, 23(1), e1963.

Liu, Z., Wang, Y., & Chen, S. (2017). Does formal housing encourage settlement intention of rural migrants in Chinese cities? A structural equation model analysis. Urban Studies, 54(8), 1834–1850.

Liu, Z., & Gu, H. (2019). Evolution characteristics of spatial concentration patterns of interprovincial population migration in China from 1985 to 2015. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 1-17.

McGranahan, D. A. (1999). Natural amenities drive rural population change (no. 1473-2016-120765).

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2018). 2017 Migrant Workers Monitoring Survey Report. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/ 201704/t20170428_1489334.html.

Rappaport, J. (2009). Moving to nice weather. In Environmental Amenities and Regional Economic Development (pp. 25–53). Routledge.

Stark, O., & Bloom, D. E. (1985). The new economics of labor migration. The American Economic Review, 75(2), 173–178.

Stillwell, J., Daras, K., & Bell, M. (2018). Spatial aggregation methods for investigating the MAUP effects in migration analysis. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 11, 693–711.

Tan, S., Li, Y., Song, Y., Luo, X., Zhou, M., Zhang, L., & Kuang, B. (2017). Influence factors on settlement intention for floating population in urban area: A China study. Quality & Quantity, 51(1), 147–176.

Tiebout, C. M. (1956). A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64(5), 416–424.

Todaro, M. P. (1969). A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries. The American Economic Review, 59(1), 138–148.

Wei, H., & Su, H. (2013). Research on Degree of Citizenization of Rural-Urban Migrants in China. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 2013(5), 21–29 (in Chinese).

Wei, Z. (2013). A region-specific comparative study of factors influencing the residing preference among migrant population in different areas: Based on the dynamic monitoring & survey data on the migrant population in five cities of China. Population & Economics, 4, 12–20 (in Chinese).

Xiang, H., Yang, J., Zhang, T., & Ye, X. (2018). Analyzing in-migrants and out-migrants in urban China. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 11, 81–102.

Xu, Z., & Ouyang, A. (2018). The factors influencing China’s population distribution and spatial heterogeneity: A prefectural-level analysis using geographically weighted regression. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 11, 465–480.

Yang, G., Zhou, C., & Jin, W. (2020). Integration of migrant workers: Differentiation among three rural migrant enclaves in Shenzhen. Cities, 96, 102453.

Yue, Z., Li, S., Feldman, M. W., & Du, H. (2010). Floating choices: A generational perspective on intentions of rural–urban migrants in China. Environment and Planning A, 42(3), 545–562.

Zhu, Y. (2007). China's floating population and their settlement intention in the cities: Beyond the Hukou reform. Habitat International, 31(1), 65–76.

Zhu, Y., & Chen, W. (2010). The settlement intention of China's floating population in the cities: Recent changes and multifaceted individual-level determinants. Population, Space and Place, 16(4), 253–267.

Zhou, L., Tian, L., Gao, Y., Ling, Y., Fan, C., Hou, D., Shen, T., & Zhou, W. (2019). How did industrial land supply respond to transitions in state strategy? An analysis of prefecture-level cities in China from 2007 to 2016. Land Use Policy, 87, 104009.

Acknowledgments

The work described in this study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.71733001), the National Social Science Foundation of China (No. 17ZDA055), and China Scholarship Council (201906010255).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors claim that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, H., Jie, Y., Li, Z. et al. What Drives Migrants to Settle in Chinese Cities: a Panel Data Analysis. Appl. Spatial Analysis 14, 297–314 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-020-09358-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-020-09358-z