Abstract

Desmoid tumor originating from the small intestine is extremely rare. We report a 50-year-old man who presented with the sudden onset of severe abdominal pain. Computerized tomography (CT) demonstrated a huge homogeneous tumor in the lower abdomen that appeared to be in continuity with the distal ileum. The mass adherent to the ileum was resected and proved to be a desmoid tumor. The patient has remained recurrence free on follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Desmoid tumors (desmoid-type fibromatosis) are rare, deep-seated, usually unencapsulated, slowly growing fibroblastic neoplasms that arise from fascial or musculoaponeurotic structures [1]. Desmoids account for about 0.03% of all neoplasms and less than 3% percent of all soft tissue tumors. The estimated incidence in the general population is two to four per million populations per year [1]. Although desmoids are considered benign because they do not metastasize, they may infiltrate adjacent tissues, causing organ disruption that may in some cases be fatal. Desmoid tumors are generally classified as intra-abdominal or extra-abdominal. Most intra-abdominal desmoids arise in the mesentery, particularly of the small bowel, and are in fact the most common primary tumor of the mesentery [1–3]. We report an intra-abdominal desmoid arising in an unusual location.

Case report

A 50-year-old man presented with the sudden onset of sharp, cramping, peri-umbilical, non-radiating pain. The pain was associated with diaphoresis, but the patient denied nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, melena, hematochezia, a change in bowel habits, or weight loss. The pain was so intense that he immediately went to the emergency room. His past medical history was unremarkable. In particular, he had no history of previous abdominal surgery.

On physical examination, he appeared to be in pain. His blood pressure was 89/60 mmHg, temperature 40.5°C, and pulse 120 beats per minute. The abdomen was distended with peri-umbilical and rebound tenderness and muscle guarding. All four extremities were cool. His leukocyte count was 3,200/mm3 with 2% bands and 78% neutrophils.

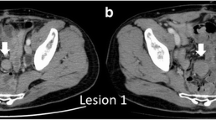

Decubitus plain abdominal radiography revealed a soft tissue density in the lower abdomen. Computerized tomography (CT) demonstrated a huge homogeneous tumor in the same area that appeared to be in continuity with the distal small intestine. There was a small loop of bowel with an air-fluid level that seemed to be encased by the tumor, suggesting possible strangulation (Fig. 1). At laparotomy, the tumor was seen to arise from the anti-mesenteric side of the ileum 60–80 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve. The tumor itself and the involved small bowel were diffusely hyperemic. The tumor and a segment of small bowel were resected. Ascites and blood culture all grew Escherichia coli.

Grossly, the resected tumor was a white-to-tan, firm, encapsulated intramural tumor (Fig. 2). Microscopically, it involved the muscularis propria and submucosal layers of the bowel wall without penetrating the overlying mucosa or invading the mesentery (Fig. 3a). It was composed of bland spindle and stellate cells arranged in sweeping bundles deposited in a dense collagenous background (Fig. 3b). The appearance was consistent with a desmoid tumor but was also reminiscent of other mesenchymal tumors. However, on immunohistochemical study, the tissue was negative for CD117, smooth muscle actin, desmin, and S-100 protein. There was also no KIT or PDGFR gene mutation, ruling out gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Mutation of the beta-catenin gene was present, supporting the diagnosis of desmoid tumor.

The patient recovered and had no evidence of tumor recurrence 24 months after resection.

Discussion

The most unusual feature of this patient’s desmoid tumor was its origin from the anti-mesenteric side of the ileum, unlike most reported abdominal desmoids that arise in the mesentery [3]. Rarely, desmoids have been reported in the esophagogastric junction [4], pancreas [5], appendix [6], and ileum [7]. Though we cannot prove it, we speculate that this patient’s tumor may have arisen from the wall of the small bowel and grown out from there.

The etiology of desmoids has not been well defined, but several factors have been implicated, including in some cases mutations in the APC and beta-catenin genes, and trisomy of chromosomes 20 and 8 [8–11]. This is why the beta-catenin gene mutation in our patient was helpful for diagnosis.

Most patients with intra-abdominal desmoids are asymptomatic for long periods. Only late in the course are there signs or symptoms such as a palpable mass, abdominal pain, or gastrointestinal bleeding [3]. Reported complications of intra-abdominal desmoids include ureteric obstruction, intestinal obstruction, intestinal ischemia, deterioration in an ileoanal anastomoses, abscess, and hepatic pneumatosis [8, 12–16]. In a few cases, desmoids have invaded the bowel wall, resulting in a fistula and translocation of intestinal bacteria into the tumor [17–19]. Our patient’s acute abdominal pain and peritonitis might have been caused by strangulation or micro-perforation of a loop of bowel by this huge tumor.

The diagnosis of a desmoid tumor can only be established histologically, and our patient’s findings were characteristic. However, various mesenchymal tumors in the gastrointestinal tract or abdominal cavity may have partially overlap of the gross appearance, histology, and immunophenotype [20]. In our patient, negative results of staining for desmin, smooth muscle actin, and S-100 excluded other mesenchymal tumors such as fibrosarcoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. The clinical, radiologic, and gross appearance of the specimen was most suggestive of gastrointestinal stromal tumor or desmoid. But as noted in the case report, the lack of staining for CD117 by immunohistochemistry and the absence of a KIT or PDGFR gene mutation were helpful in ruling out the former [20, 21], while the beta-catenin gene mutation was consistent with the diagnosis of a desmoid tumor.

Despite complete resection with negative microscopic margins, desmoid tumors have recurrence rate of about 40% [1, 22, 23]. It is therefore suggested that surgery should be performed only when absolutely necessary [9]. This was the case with our patient who had a potentially life-threatening complication. He has remained recurrence free for 2 years. There is no standard protocol for follow-up of patients with desmoid tumors, but we have followed him clinically and performed a CT in the 1 year after surgery.

In conclusion, we report a case of a desmoid tumor arising from the anti-mesenteric side of the small bowel. Despite the unusual location, both histology and genetic study helped confirm the diagnosis.

References

Shields CJ, Winter DC, Kirwan WO, Redmond HP. Desmoid tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001;27:701–6.

Einstein DM, Tagliabue JR, Desai RK. Abdominal desmoids: CT findings in 25 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:275–9.

Burke AP, Sobin LH, Shekitka KM, Federspiel BH, Helwig EB. Intra-abdominal fibromatosis. A pathologic analysis of 130 tumors with comparison of clinical subgroups. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:335–41.

Koyluoglu G, Yildiz E, Koyuncu A, Atalar M. Management of an esophagogastric fibromatosis in a child: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:640–2.

Bruce JM, Bradley EL 3rd, Satchidanand SK. A desmoid tumor of the pancreas. Sporadic intra-abdominal desmoids revisited. Int J Pancreatol. 1996;19:197–203.

Furie DM, et al. Mesenteric desmoid of the appendix—a case report. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 1991;15:117–20.

Singh N, Sharma R, Dorman SA, Dy VC. An unusual presentation of desmoid tumor in the ileum. Am Surg. 2006;72:821–4.

Clark SK, Neale KF, Landgrebe JC, Phillips RK. Desmoid tumours complicating familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1185–9.

Ballo MT, Zagars GK, Pollack A, Pisters PW, Pollack RA. Desmoid tumor: prognostic factors and outcome after surgery, radiation therapy, or combined surgery and radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:158–67.

Lynch HT, Fitzgibbons R Jr. Surgery, desmoid tumors, and familial adenomatous polyposis: case report and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2598–601.

Tejpar S, et al. Predominance of beta-catenin mutations and beta-catenin dysregulation in sporadic aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumor). Oncogene. 1999;18:6615–20.

Church JM. Mucosal ischemia caused by desmoid tumors in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis: report of four cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:661–3.

Sagar PM, Moslein G, Dozois RR. Management of desmoid tumors in patients after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1350–5. (discussion 1355-6).

Penna C, et al. Operation and abdominal desmoid tumors in familial adenomatous polyposis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177:263–8.

Cholongitas E, et al. Desmoid tumor presenting as intra-abdominal abscess. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:68–9.

Prat A, Peralta S, Cuellar H. Ocana A: hepatic pneumatosis as a complication of an abdominal desmoid tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:897–8.

Doi K, et al. Large intra-abdominal desmoid tumors in a patient with familial adenomatosis coli: their rapid growth detected by computerized tomography. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:595–8.

Maldjian C, Mitty H, Garten A, Forman W. Abscess formation in desmoid tumors of gardner’s syndrome and percutaneous drainage: a report of three cases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1995;18:168–71.

Faria SC, Iyer RB, Rashid A, Ellis L, Whitman GJ. Desmoid tumor of the small bowel and the mesentery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:118.

Abraham SC. Distinguishing gastrointestinal stromal tumors from their mimics: an update. Adv Anat Pathol. 2007;14:178–88.

Tzen CY, Mau BL. Analysis of CD117-negative gastrointestinal stromal tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1052–5.

Nuyttens JJ, Rust PF, Thomas CR Jr, Turrisi AT 3rd. Surgery versus radiation therapy for patients with aggressive fibromatosis or desmoid tumors: a comparative review of 22 articles. Cancer. 2000;88:1517–23.

Rampone B, Pedrazzani C, Marrelli D, Pinto E, Roviello F. Updates on abdominal desmoid tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;3:5985–8.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M.J. Buttrey for revision of the English manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, CW., Wang, TE., Chang, WH. et al. Unusual presentation of desmoid tumor in the small intestine: a case report. Med Oncol 28, 159–162 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-010-9429-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-010-9429-z