Abstract

Introduction

Brain swelling is an unusual complication of superior vena cava syndrome. It is unknown if the condition is reversible.

Case

We present a 58 year old woman with metastatic colon carcinoma presenting with facial swelling and upper trunk ecchymosis, rapid onset of coma and extensor posturing on admission. CT showed diffuse cerebral edema and evolving parenchymal hypodensities. An occlusive thrombus at the site of an indwelling intravascular access was successfully removed with thrombectomy,but the patient progressed to brain death.

Conclusion

This is the first case of fatal cerebral edema from a superior vena cava syndrome. The underlying malignancy may have induced a clotting disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A 58-year-old woman with metastatic colon cancer presented with headache, confusion, and swelling of the face, neck, and upper trunk associated with ecchymoses. Within hours of initial evaluation, she developed rapid deterioration in her level of consciousness. She was intubated and transferred to our hospital. On arrival, she was comatose with extensor posturing and hypotensive, despite echocardiography showing a relatively preserved left ventricular ejection fraction and only moderate pericardial effusion with no signs of tamponade. An occlusive thrombosis of the superior vena cava (SVC) at the site of an indwelling intravascular access was diagnosed by CT scan and confirmed angiographically and successfully treated with thrombectomy and stenting (Fig. 1). However, the patient failed to improve neurologically and hemodynamically. She lost upper brainstem reflexes within 2 h. A trial of hyperventilation had no beneficial effect and osmotherapy was not attempted due to the ominous prognosis and the family decision to withdraw life support. Serial CT scans of the brain revealing massive progression of brain swelling are shown in Fig. 2.

(a) CT scan of the chest showing an acute thrombus in the SVC surrounding an indwelling catheter (arrow). (b) SVC occlusion confirmed by conventional angiography. (c) Reopening of the SVC after thrombectomy. (d) Final angiographic result after stenting (arrows indicating the stent) showing adequate recanalization of the SVC. There was good filling of both internal jugular veins (not shown)

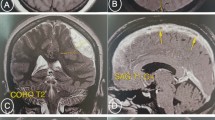

Upper row: Initial head CT scan with diffuse sulci effacement and loss of white–gray matter differentiation. Lower row: Second head CT with massive swelling of brain, optic nerves (arrow heads), and also the scalp (arrow heads). Note effacement of perimesencephalic cisterns (large arrows), evolving parenchymal hypodensities (small arrows), and high-attenuation changes in tentorium and retina from vascular congestion

Fatal brain swelling is a highly unusual complication of SVC syndrome [1, 2]. Although cases related to intravascular devices are commonly benign [2], our patient’s malignancy may have induced a state of thrombophilia. The severity of this case may be due to sudden occlusion of the SVC without time for opening of collateral pathways [1]. The resulting venous hypertension raised intracranial pressure by increasing cerebral blood volume, producing vasogenic edema and ultimately causing cytotoxic edema in areas of infarction, eventually leading to brain tissue shift and brainstem compression. The lack of clinical improvement after recanalization of the SVC was likely due to the presence of irreversible brain injury from severe intracranial hypertension with secondary global anoxia before the procedure was performed.

References

Wilson LD, Detterbeck FC, Yahalom J. Clinical practice. Superior vena cava syndrome with malignant causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1862–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp067190.

Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006;85:37–42. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000198474.99876.f0.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rabinstein, A.A., Wijdicks, E.F.M. Fatal Brain Swelling due to Superior Vena Cava Syndrome. Neurocrit Care 10, 91–92 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-008-9129-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-008-9129-0