Abstract

Background

Interest in developing national health care has been increasing in many fields of medicine, including orthopaedics. One manifestation of this interest has been the development of global health opportunities during residency training.

Questions/purposes

We assessed global health activities and opportunities in orthopaedic residency in terms of resident involvement, program characteristics, sources of funding and support, partner site relationships and geography, and program director opinions on global health participation and the associated barriers.

Methods

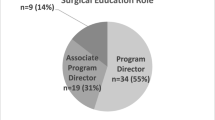

An anonymous 24-question survey was circulated to all US orthopaedic surgery residency program directors (n = 153) by email. Five reminder emails were distributed over the next 7 weeks. A total of 59% (n = 90) program directors responded.

Results

Sixty-one percent of responding orthopaedic residencies facilitated clinical experiences in developing countries. Program characteristics varied, but most used clinical rotation or elective time for travel (76%), which most frequently occurred during Postgraduate Year 4 (57%) and was used to provide pediatric (66%) or trauma (60%) care. The majority of programs (59%) provided at least some funding to traveling residents and sent accompanying attendings on all ventures (56%). Travel was most commonly within North America (85%), and 51% of participating programs have established international partner sites although only 11% have hosted surgeons from those partnerships. Sixty-nine percent of residency directors believed global health experiences during residency shape future volunteer efforts, 39% believed such opportunities help attract residents to a training program, and the major perceived challenges were funding (73%), faculty time (53%), and logistical planning (43%).

Conclusions

Global health interest and activity are common among orthopaedic residency programs. There is diversity in the characteristics and geographical locations of such activity, although some consensus does exist among program directors around funding and faculty time as the largest challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The unmet need for orthopaedic care in developing nations has received attention in the literature for several decades [7, 27]. Musculoskeletal conditions, especially traumatic injuries and sequelae, account for a substantial portion of the total global burden of disease, but there is a dramatic shortage of resources and providers available to address this problem [20, 29]. Among the most prominent orthopaedic initiatives in developing nations are the distribution of low-cost implants by the Surgical Implant Generation Network (SIGN) and the dissemination of education by Health Volunteers Overseas (HVOS) [5, 7, 26, 30]. The case has also been made for the benefits of short-term volunteer efforts, including those provided by residents, fellows, and recent graduates from orthopaedic residency programs [9].

Recent surveys have demonstrated a major interest in global health pursuits among surgical trainees [2, 3, 12, 22], including orthopaedic residents [14, 17]. Additionally, several surgical residency programs have published detailed descriptions of their global health opportunities [15, 21, 23, 28], including at least one orthopaedic program [11, 24]. Prior research has examined the development of global health training opportunities within residency programs across other specialties in the healthcare field and studied the opinions of residency program directors on the topic of international volunteer opportunities for residents [4, 13, 16, 19]. However, to our knowledge, the topic has not been studied in orthopaedics.

Thus, we (1) assessed the level of resident involvement in global health opportunities among orthopaedic residency programs in the United States; (2) determined the characteristics of opportunities currently available to residents; (3) identified sources of funding and support from residency programs; (4) described the geographic distribution of international resident experiences and relationships with partner sites; and (5) explored program directors’ opinions of global health participation and the associated barriers.

Materials and Methods

A 24-question survey (Table 1) was distributed by email to the program directors of the 153 orthopaedic residency programs in the United States. Five reminder emails were sent over the subsequent 7 weeks. To assess the characteristics of existing opportunities, the survey strives to distinguish between residencies with organized global health programs that, for example, make international opportunities available to trainees with a structured support system, possibly including funding and established international partner sites, versus residencies that simply allow motivated residents to organize and participate in their own international orthopaedic experiences. To make this assessment, each respondent was asked if their residency had a “structured global health program”; the exact definition of that term was left to the respondent’s interpretation. The survey was anonymous but did contain an optional response for the name of the responding program with the stated sole purpose of eliminating unnecessary reminder emails. Data were collected with the Google Docs online survey tool (Google Inc, Mountain View, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using Microsoft® Excel® (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA).

The response rate was 59% (n = 90).

Results

The majority of programs that responded provided global health opportunities to residents. Fifty-five responding residency programs (61%) reported that at least one resident had participated in an orthopaedic experience in a developing country in the past 5 years. Twenty percent of these 55 residencies, and 12% of all respondents (11 programs), reported having a “structured global health program.” These programs have been in place for a mean ± SD of 9.2 ± 10.8 years with a maximum of 42 years. Among residencies without structured global health programs, 15 of 62 respondents (24%) planned to develop such a program, 11 (18%) considered and decided against establishing a program, and 29 (47%) reported that it has not been considered. Of the 55 residencies reporting global health activity, only 10% send the majority of trainees abroad (Fig. 1).

A bar graph demonstrates the variation in resident involvement in global health experiences among residency programs. Of the 55 respondents, 27 (49%) reported approximately one resident every few years traveled to a developing country, whereas five (9%) reported at least half of their residents embarked on such a trip.

The characteristics of global health opportunities described by respondents were diverse. The mean length of abroad rotations, as reported by nine respondents, was 2.1 ± 1.2 weeks (range, 1–4 weeks). Time allocation occurred mainly during Postgraduate Year (PGY)-4 clinical time with most efforts dedicated to clinical work in the subspecialties of trauma and pediatrics (Fig. 2).

Bar graphs depict the (A) year, (B) time, (C) specialty involved in the global health experiences of residents, and (D) their activities while abroad. (A) Most global health experiences occurred during PGY-4 (57%), whereas PGY-3 and PGY-5 were also popular choices. (B) Most residents traveling abroad used clinical time (76%), either core rotations or electives, whereas vacation (37%) and research time (19%) were also common answers. Only one program provided dedicated global health time for residents. (C) The most common types of subspecialty care provided by residents abroad were pediatrics (66%) and trauma care (60%) followed by general orthopaedics (45%). (D) The most common activity while abroad was clinical work (91%), whereas 75% reported teaching local providers occupied at least a little resident time abroad. GH = global health.

Many residencies provide financial and faculty support for global health opportunities. The majority of respondents with global health activity provide at least some funding to traveling residents, most often through orthopaedic department funds (Fig. 3A–B). Most programs report that all trips are accompanied by an attending surgeon, but a clear minority of faculty members have been involved in such travel in the last 5 years (Fig. 3C–D). A handful of respondents reported external support through partnerships with American nonprofit organizations; specifically mentioned were SIGN, HVOS, Mercy Ships, and a potential future arrangement with the Orthopaedic Trauma Association’s International Committee.

Bar graphs demonstrate (A) percentage of residents’ traveling expenses covered by the residency program, (B) source of funding, (C) percentage of residents accompanied by faculty, and (D) percentage of faculty participating in global health experiences for residents. (A) Only 59% provided some funding for residents traveling abroad and 39% covered at least half of all travel expenses. (B) The most common source of global health funding was orthopaedic departments (60% at least a moderate funder) followed by donations and private grants. (C) Faculty support mostly came from within the department; 56% reported that at least 75% of such travels was accompanied by an attending surgeon from the department. (D) Eighty-nine percent reported between 1% and 25% of their attendings have participated in global health work with only one program reporting no global health activity among attendings.

Respondents report travel to five continents with North America being the most common destination and Haiti ranking as the most frequently visited country (Table 2). A slight majority of programs with global health activity send all traveling residents to prearranged sites and report having established relationships with at least one partner site (eg, a hospital, clinic, university, etc) abroad, but a minority have hosted surgeons or trainees from those sites (Fig. 4). Only one respondent hosted more than 10 such visitors annually.

Bar graphs demonstrate (A) how residents choose destination sites, (B) how many partner sites residency programs have established, and (C) reciprocal hosting policies with partner sites. (A) Most residents sought their own global heath opportunities (43%) followed by all traveling to the same destination (36%) or choosing from a list of prearranged options (15%). (B) Fifty-one percent of residencies with resident global health activity had ongoing relationships with at least one partner site abroad (eg, hospital, clinic, university, etc), and three had five or more such relationships. (C) Forty-three percent of these residency programs hosted orthopaedic surgeons from their partner sites on a regular basis with one respondent hosting more than 10 annually.

Although program directors’ opinions about resident experiences were positive, there were mixed responses about the benefits and challenges of implementation. Nearly all respondents felt that residents typically had “very good” or “excellent” experiences abroad and a majority believed that global health opportunities during residency play a major role in shaping future professional and/or volunteer activities, but there was no clear consensus on the importance of global health opportunities in attracting residency applicants (Fig. 5A–C). Program directors tended to think the largest barriers to developing global health programs were limited funding, limited faculty time, logistical planning, and low faculty interest (Fig. 5D).

Pie charts and a stacked bar graph depict residency director opinions on the benefits and barriers associated with providing global health opportunities for residents, including (A) residents’ satisfaction with global health experiences, (B) role of such experiences in shaping future professional and/or volunteer activities, (C) role of such activities in attracting applicants to residency programs, and (D) challenges to providing global health opportunities. (A) Most residents (96%) had very good or excellent experiences abroad. (B) Sixty-nine percent of directors believed global health opportunities during residency play a major role in shaping future professional and/or volunteer activities, whereas 12% disagreed with this assertion. (C) Thirty-nine percent believed such opportunities play a major role in attracting applicants to a residency program, whereas 32% disagreed. (D) The largest reported barrier to developing global health programs was limited funding (90% at least a moderate barrier). Other commonly cited barriers were limited faculty time, logistical planning, and low faculty interest.

Discussion

Recent literature suggests strong global health interest exists among residents, including surgical trainees [3, 12, 22] and, specifically, orthopaedists [14, 17]. Similarly, numerous studies indicate a growing amount of global health activity within residency programs [4, 11, 13, 19, 23]. Research has been conducted in several specialties to evaluate the level and nature of global health activity facilitated by residencies [13, 16, 19], but to date, no such study has been undertaken in orthopaedics. The goal of this national survey was to assess the current level and structure of global health opportunities among US orthopaedic residency programs, including financial and faculty support, geographic distribution, international partnerships, and residency director opinions on the benefits and challenges of such activity.

This study has a number of limitations. The response rate of 59% indicates that our results are not perfectly generalizable but is firmly in line with published survey studies [1, 6], including surveys on global health sent to residency directors in other specialties [13, 16, 19, 25]. Additionally, the results may be affected by response bias because it is possible that residency directors with enthusiastic opinions on global health and who have developed global health opportunities within their programs were more likely to complete the survey. Lastly, by nature, data collected solely by survey are unsubstantiated and subjective, which is especially relevant for the results presented here on perceived barriers to the development of global health opportunities.

Our results indicate that global health activity is present at 61% of responding residencies, and 36% of these report a structured global health program. This is consistent with levels of global health activity at US residencies in other specialties as reported by previous survey studies, including 57% of programs in internal medicine [16], 53% in pediatrics [19], 45% in family medicine [25], 71% in emergency medicine [8], and 29% in general surgery [13]. A Canadian survey of residents in both general and orthopaedic surgery suggested that 71% of Canadian programs in these fields have elective time that can be used for international experiences [17]. Additionally, 59% of allopathic US medical schools have been reported to offer international global health electives [18]. Our results suggest the level of global health involvement in US orthopaedic residencies may be a growing trend, because 24% of programs without structured global health programs are considering the development of such opportunities. This trend is consistent with prior research demonstrating interest in global health among orthopaedic trainees [14, 17] as well as increasing levels of global health activity among medical students before graduation [10].

There is substantial variety in the characteristics of global health activity among residencies, but the most common structure involves sending residents abroad during the second half of their training for approximately 2 weeks in place of clinical rotations at home, most frequently to participate in the delivery of pediatric and trauma care. Again, this is similar to reports from other specialties that have described travel in the latter half of residency [13, 16, 19] with a focus on clinical work [13].

Our results demonstrate that most orthopaedic residencies with global health activity offer financial and faculty support to involved residents with 59% of programs covering at least some travel expenses, typically using departmental funds. This compares favorably with previous literature suggesting that 41% of residencies with global health activity provide at least partial funding in the field of internal medicine [16], 42% in pediatrics [19], and 43% in general surgery [13]. Among internal medicine programs, donations were the most common source (43%) followed by departmental funds (27%) and educational endowments (26%) [16]. Our study suggests that 89% of orthopaedic residencies facilitating global health travel have attending participation on at least some international trips. This finding is in line with previous research reporting 90% faculty involvement among internal medicine programs [16] and 76% among general surgery programs [13]. Eighty-two percent of pediatric programs reported “faculty mentorship,” which included domestic faculty-resident interactions [19].

Global health travel among orthopaedic residents spans five continents but is most often within North America, and specifically to Haiti, likely inspired in part, as one respondent noted, by the 2010 earthquake. Prior research has not elaborated on the geography of destination sites within other specialties, but among internal medicine programs, 41% facilitate travel to designated sites, similar to the 51% of orthopaedic programs observed in this study [16]. Forty-three percent of orthopaedic programs with international partnerships have hosted providers from those sites; 20% has been reported among general surgery programs [13].

Our finding that 39% of residency directors believe global health opportunities play a major role in attracting applicants, whereas 32% disagree is inverted compared with findings in internal medicine in which 30% felt such opportunities were important for recruitment, whereas 49% disagreed [16]. Forty-three percent of general surgery residencies with global health activity reported resident recruitment as one of their goals [13]. The top barriers to such activity reported in this study were funding, faculty time, and logistical planning. Funding was also listed as a common barrier by internal medicine program directors [16] and was the third largest challenge reported by general surgery program directors following time restraints on trainees and concern that international work may not fulfill accreditation requirements as defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education [13]. Limited call-free elective time was reported as the largest challenge in pediatrics [19].

In conclusion, global health opportunities are common among US orthopaedic residencies, and the level, characteristics, and challenges of such activity described in this study are consistent with previous reports from other specialties. Levels of faculty and financial support as well as reciprocal hosting may be favorable when compared with other specialties. The various approaches to global health described in this article could potentially serve as examples for residency programs building or refining their global health opportunities. Additionally, the amount of activity already in place should be an encouragement to program directors considering developing global health experiences. Many residency directors and other attendings have substantial experience in the delivery of orthopaedic care in developing nations and could potentially serve as valuable resources in the development of new global health opportunities. Still, much remains unknown, and we hope our findings might set the groundwork for additional research, especially with regard to the educational value for traveling residents, the financial realities of operating global health programs, the speculative information provided here by residency directors on resident recruitment and barriers to implementation, and the quality of care provided abroad, particularly given the potential for poor postoperative followup after traveling providers return home. As more becomes known about the outcomes of orthopaedic global health efforts and the impact on local populations, the ethics of such work must also be considered.

References

Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129–1136.

Boyd NH, Cruz RM. The importance of international medical rotations in selection of an otolaryngology residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3:414–416.

Butler MW, Krishnaswami S, Rothstein DH, Cusick RA. Interest in international surgical volunteerism: results of a survey of members of the American Pediatric Surgical Association. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:2244–2249.

Campagna AM, St Clair NE, Gladding SP, Wagner SM, John CC. Essential factors for the development of a residency global health track. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51:862–871.

Coughlin RR, Kelly NA, Berry W. Nongovernmental organizations in musculoskeletal care: Orthopaedics Overseas. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2438–2442.

Cummings SM, Savitz LA, Konrad TR. Reported response rates to mailed physician questionnaires. Health Serv Res. 2001;35:1347–1355.

Derkash RS, Kelly N. The history of orthopaedics overseas. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002:30–35.

Dey CC, Grabowski JG, Gebreyes K, Hsu E, VanRooyen MJ. Influence of international emergency medicine opportunities on residency program selection. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:679–683.

Dormans JP. Orthopaedic surgery in the developing world—can orthopaedic residents help? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1086–1094.

Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, Hall TL, Gardner P. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med. 2009;84:320–325.

Haskell A, Rovinsky D, Brown HK, Coughlin RR. The University of California at San Francisco international orthopaedic elective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;396:12–18.

Javidnia H, McLean L. Global health initiatives and electives: a survey of interest among Canadian otolaryngology residents. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;40:81–85.

Jayaraman SP, Ayzengart AL, Goetz LH, Ozgediz D, Farmer DL. Global health in general surgery residency: a national survey. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:426–433.

Jense RJ, Howe CR, Bransford RJ, Wagner TA, Dunbar PJ. University of Washington orthopedic resident experience and interest in developing an international humanitarian rotation. Am J Orthop. 2009;38:E18–20.

Klaristenfeld DD, Chupp M, Cioffi WG, White RE. An international volunteer program for general surgery residents at Brown Medical School: the Tenwek Hospital Africa experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:125–128.

Kolars JC, Halvorsen AJ, McDonald FS. Internal medicine residency directors perspectives on global health experiences. Am J Med. 2011;124:881–885.

Matar WY, Trottier DC, Balaa F, Fairful-Smith R, Moroz P. Surgical residency training and international volunteerism: a national survey of residents from 2 surgical specialties. Can J Surg. 2012;55:S191–199.

McKinley DW, Williams SR, Norcini JJ, Anderson MB. International exchange programs and US medical schools. Acad Med. 2008;83:S53–57.

Nelson BD, Lee AC, Newby PK, Chamberlin MR, Huang C-C. Global health training in pediatric residency programs. Pediatrics. 2008;122:28–33.

Noordin S, Wright JG, Howard AW. Global relevance of literature on trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2422–2427.

Ozgediz D, Wang J, Jayaraman S, Ayzengart A, Jamshidi R, Lipnick M, Mabweijano J, Kaggwa S, Knudson M, Schecter W, Farmer D. Surgical training and global health: initial results of a 5-year partnership with a surgical training program in a low-income country. Arch Surg. 2008;143:860–865; discussion 865.

Powell AC, Mueller C, Kingham P, Berman R, Pachter HL, Hopkins MA. International experience, electives, and volunteerism in surgical training: a survey of resident interest. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:162–168.

Qureshi JS, Samuel J, Lee C, Cairns B, Shores C, Charles AG. Surgery and global public health: the UNC-Malawi surgical initiative as a model for sustainable collaboration. World J Surg. 2011;35:17–21.

Rovinsky D, Brown HP, Coughlin RR, Paiement GD, Bradford DS. Overseas volunteerism in orthopaedic education. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:433–436.

Schultz SH, Rousseau S. International health training in family practice residency programs. Fam Med. 1998;30:29–33.

Shearer D, Zirkle LG. Future directions for assisting orthopedic surgery in the developing world. Techniques in Orthopaedics. 2009;24:312–315.

Silva JF. The urgent need to train orthopaedic surgeons in Third World countries. Med Educ. 1979;13:28–30.

Silverberg D, Wellner R, Arora S, Newell P, Ozao J, Sarpel U, Torrina P, Wolfeld M, Divino C, Schwartz M, Silver L, Marin M. Establishing an international training program for surgical residents. J Surg Educ. 2007;64:143–149.

Spiegel DA, Gosselin RA, Coughlin RR, Kushner AL, Bickler SB. Topics in global public health. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2377–2384.

Young S, Lie SA, Hallan G, Zirkle LG, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Low infection rates after 34,361 intramedullary nail operations in 55 low- and middle-income countries: validation of the Surgical Implant Generation Network (SIGN) online surgical database. Acta Orthop. 2011;82:737–743.

Acknowledgments

We thank the orthopaedic residency program directors who took the time to respond to this survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved or waived approval for the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

About this article

Cite this article

Clement, R.C., Ha, Y.P., Clagett, B. et al. What Is the Current Status of Global Health Activities and Opportunities in US Orthopaedic Residency Programs?. Clin Orthop Relat Res 471, 3689–3698 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-3184-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-3184-3