Abstract

Recent studies suggest US medical schools are not effectively addressing musculoskeletal medicine in their curricula. We examined if there were specific areas of weakness by analyzing students’ knowledge of and confidence in examining specific anatomic regions. A cross-sectional survey study of third- and fourth-year students at Harvard Medical School was conducted during the 2005 to 2006 academic year. One hundred sixty-two third-year students (88% response) and 87 fourth-year students (57% response) completed the Freedman and Bernstein cognitive mastery examination in musculoskeletal medicine and a survey eliciting their clinical confidence in examining the shoulder, elbow, hand, back, hip, knee, and foot on a one to five Likert scale. We specifically analyzed examination questions dealing with the upper extremity, lower extremity, back, and others, which included more systemic conditions such as arthritis, metabolic bone diseases, and cancer. Students failed to meet the established passing benchmark of 70% in all subgroups except for the others category. Confidence scores in performing a physical examination and in generating a differential diagnosis indicated students felt below adequate confidence (3.0 of 5) in five of the seven anatomic regions. Our study provides evidence that region-specific musculoskeletal medicine is a potential learning gap that may need to be addressed in the undergraduate musculoskeletal curriculum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal conditions comprise a substantial portion of patient visits in a wide range of clinical practice, accounting for nearly 20% of complaints and injuries in the emergency room [5], 20% of nonroutine pediatric visits [4], and 15% to 30% of primary care visits [10]. According to the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, musculoskeletal complaints accounted for approximately 92.1 million cases in 2004 and were the number one reason for visits to physicians’ offices [8].

The frequency of musculoskeletal complaints that arise in clinical practice dictates that all medical students should be well versed in musculoskeletal medicine. However, recent studies suggest medical schools do not provide adequate musculoskeletal education in their curricula. Students not only failed to show cognitive mastery in musculoskeletal medicine [3, 9, 11] as measured by Freedman and Bernstein’s validated musculoskeletal examination [7], but also lacked clinical confidence in examining the musculoskeletal system and believed the amount of curricular time spent in musculoskeletal medicine was poor [3]. Yeh et al. recently reported that only students interested in orthopaedic residencies met the passing criterion for Freedman and Bernstein’s examination and exhibited above average clinical confidence [12]. Not surprisingly, several studies assessing US residency programs suggest residents also did not show basic competency in musculoskeletal medicine [7, 9] and felt poorly prepared to perform a musculoskeletal examination on various parts of the body [2].

However, few studies have focused on identifying specific learning gaps in the undergraduate musculoskeletal curriculum, which if appropriately identified, could assist efforts at curricular reform. One study in 2005 examined medical students’ knowledge in musculoskeletal medicine with respect to several categories, including oncology, pediatrics, sports, spine, and trauma using a considerably shortened version of Freedman and Bernstein’s examination [11]. They noted the lowest number of correct answers in spine, but the mean rate for all questions was 61%.

We therefore reexamined survey results from a previous study [12] and focused on region-specific musculoskeletal medicine, which included previously unpublished data. We investigated whether medical students in their clinical years of training exhibited particular areas of deficiency in our musculoskeletal curriculum by evaluating their cognitive mastery of musculoskeletal medicine in specific anatomic regions and in more systemically relevant topics. We also evaluated the same students’ level of confidence in performing a physical examination and in generating a differential diagnosis for seven anatomic regions.

Materials and Methods

We analyzed data from a cross-sectional survey study of all 4 years of medical students performed at Harvard Medical School during the 2005 to 2006 academic year. Recruitment methods are described in detail in an earlier report [3]. All participating students completed Freedman and Bernstein’s nationally validated cognitive mastery examination in musculoskeletal medicine consisting of 25 short answer questions [7] and a survey that elicited students’ confidence in performing physical examinations and in generating differential diagnoses for various musculoskeletal anatomic regions. Students were not allowed to use outside resources and were given as much time as needed for completion of the examination. The passing criterion for the examination of 70% was determined by 240 internal medicine residency program directors across the United States reflecting what they believed medical school graduates should know [7]. For this study, we only used data from the 162 third-year (88% response rate for third-year class) and 87 fourth-year students (57% response rate), because those students have experienced the majority of the medical curriculum. Analysis regarding the influence of residency interest and clinical electives on students’ musculoskeletal education using this data set has been reported [12].

To assess students’ cognitive mastery of different anatomic regions, we analyzed Freedman and Bernstein’s 25-question examination according to four separate categories: “upper extremity,” “lower extremity,” “back,” and “others,” which included more systemic conditions such as metabolic disorders, arthritis, and cancer (Table 1). Thirty-four third-year students and three fourth-year students reported prior exposure to the examination, most commonly from reading the original article by Freedman and Bernstein, which contained the accepted responses [7]. We excluded the examination scores of these students from the cognitive mastery analysis.

Clinical confidence levels in performing a physical examination and in generating a differential diagnosis were measured for seven areas of the musculoskeletal system, including the shoulder, elbow, hand and wrist, back, hip, knee, and foot and ankle. Self-reported confidence levels also were elicited for the musculoskeletal system as a whole and for the pulmonary system for comparison. The pulmonary system was chosen because musculoskeletal and respiratory symptoms comprise the top two reasons for visits to a physician’s office [8]. Scores were reported on a five-point Likert scale (1 = none, 2 = low, 3 = adequate, 4 = high, 5 = complete confidence). The two questions asked for each category were: (1) “How would you rate your level of confidence in doing a physical examination on the listed body parts or system?”; and (2) “How would you rate your level of confidence in making a differential diagnosis for pain in those areas?” One third-year and one fourth-year student did not complete the subjective portion of the survey.

We used two-tailed Student’s t-tests to compare the overall cognitive mastery examination scores with each anatomic region and clinical confidence between regions and one-sample t-test to determine whether students’ clinical confidence in various anatomic regions was considerably below average confidence. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Examination scores suggested a large discrepancy between students’ knowledge in region-specific and more systemic musculoskeletal medicine. Compared with the overall third-year examination score, third-year students performed worse on questions related to the back (p < 0.0001), lower extremity (p = 0.0002), and upper extremity (p = 0.004) (Fig. 1A). The average examination score for the others category was higher (p < 0.0001) than the overall third-year performance and was the only category in which students met the passing criterion of 70% [7]. Compared with the overall fourth-year examination score, fourth-year students also performed worse on questions related to the back (p < 0.0001), lower extremity (p = 0.03), and upper extremity (p = 0.010) (Fig. 1B). The average examination score for the others category was higher (p < 0.0001) than the overall fourth-year performance and also was the only category in which students met the passing criterion. There was significant improvement in performance from third year to fourth year with respect to the overall score (p = 0.0002), upper extremity (p = 0.03), lower extremity (p = 0.002), and back (p < 0.0001), whereas there was no significant improvement in the scores for the others category (Fig. 1).

(A) Competency examination scores of third-year students divided by categories (N = 128) are shown: examination scores (mean ± 95% CI of mean): overall (54.8 ± 2.59); back (29.2 ± 3.50); lower extremity (45.4 ± 4.24); upper extremity (48.2 ± 3.79); others (76.9 ± 3.52). (B) The competency examination scores of fourth-year students divided by categories (N = 84) are shown: examination scores (mean ± 95% CI of mean): overall (62.1 ± 2.88); back (43.2 ± 4.83); lower extremity (55.7 ± 5.28); upper extremity (54.9 ± 4.73); others (80.1 ± 3.22). CI = confidence interval.

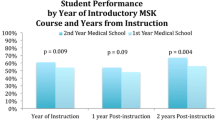

Students showed inadequate clinical confidence in performing a physical examination for the musculoskeletal system as a whole and for the majority of anatomic regions (Fig. 2A). Third- and fourth-year students were more confident (p < 0.0001 for both years) in performing a physical examination for the pulmonary system compared with the musculoskeletal system [3]. Third-year students were below (p < 0.0001 in all six categories) adequate confidence (three of five) for six anatomic regions and were only above adequate for examining the knee (Fig. 2A). Fourth-year students were below (p < 0.0001 in all five categories) adequate confidence in five regions and were only above adequate for the knee (Fig. 2A). Confidence in examining the back was below adequate for the fourth-year students, but results were not significant (p = 0.2670) (Fig. 2A). The only region fourth-year students showed a higher level of confidence than third-year students was in the back (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A).

(A) The clinical confidence scores in performing a physical examination for third- and fourth-year students (N = 161) are shown. Numeric scales were categorized as: 1 = no confidence; 2 = low confidence; 3 = adequate confidence; 4 = high confidence; 5 = complete confidence. Scores (mean ± 95% CI of mean): overall pulmonary system: third year (4.00 ± 0.13), fourth year (4.00 ± 0.18); overall musculoskeletal system: third year (2.60 ± 0.11), fourth year (2.65 ± 0.15); shoulder: third year (2.60 ± 0.12), fourth year (2.62 ± 0.15); elbow: third year (2.52 ± 0.13), fourth year (2.49 ± 0.17); hand/wrist: third year (2.71 ± 0.14), fourth year (2.53 ± 0.18); back: third year (2.44 ± 0.14), fourth year (2.90 ± 0.19); knee: third year (3.14 ± 0.15), fourth year (3.23 ± 0.20); hip: third year (2.64 ± 0.13), fourth year (2.64 ± 0.19); foot/ankle: third year (2.46 ± 0.14), fourth year (2.51 ± 0.16). (B) Clinical confidence scores in generating a differential diagnosis for third- and fourth-year students (N = 86) are shown. Numeric scales were categorized as: 1 = no confidence; 2 = low confidence; 3 = adequate confidence; 4 = high confidence; 5 = complete confidence. Scores (mean ± 95% CI of mean): overall pulmonary system: third year (3.71 ± 0.13), fourth year (3.84 ± 0.19); overall musculoskeletal system: third year (2.35 ± 0.11), fourth year (2.57 ± 0.14); shoulder: third year (2.35 ± 0.12), fourth year (2.51 ± 0.15); elbow: third year (2.27 ± 0.12), fourth year (2.39 ± 0.15); hand/wrist: third year (2.47 ± 0.14), fourth year (2.46 ± 0.15); back: third year (2.52 ± 0.14), fourth year (3.06 ± 0.19); knee: third year (2.67 ± 0.13), fourth year (3.01 ± 0.19); hip: third year (2.35 ± 0.12), fourth year (2.94 ± 0.16); foot/ankle: third year (2.32 ± 0.12), fourth year (2.37 ± 0.14). CI = confidence interval.

Students also had inadequate clinical confidence in generating a differential diagnosis for the musculoskeletal system as a whole and for the majority of anatomic regions (Fig. 2B). Third- and fourth-year students were more confident (p < 0.0001 for both years) in generating a differential diagnosis for the pulmonary system compared with the musculoskeletal system (Fig. 2B). Third-year students were below (p < 0.0001 in all categories) adequate confidence for all anatomic regions (Fig. 2B). Fourth-year students were below adequate confidence in four regions (p < 0.0001 in all four categories) and were above adequate for the knee and back (Fig. 2B). Fourth-year students exhibited a higher level of confidence than third-year students for the back (p < 0.0001) and the knee (p = 0.004) (Fig. 2B).

Discussion

We previously examined the overall effectiveness of the musculoskeletal curriculum at our medical institution and concluded the existing curriculum was inadequate [3]. A followup report indicated that only those interested in orthopaedics showed cognitive mastery and adequate clinical confidence in musculoskeletal medicine; and a mandatory clinical clerkship in orthopaedics considerably improved students’ attitude, knowledge, and confidence in the field [12]. To gain further insight on specific areas of weakness in the musculoskeletal curriculum so appropriate curricular changes can be made, we analyzed students’ knowledge and clinical confidence with respect to specific anatomic regions.

Our results must be taken in the context of several limitations. First, as a single-institution study, our population and curriculum content may not represent those of other medical institutions. However, the inadequacy in the musculoskeletal curriculum seen at our institution is likely pertinent to other medical schools. Currently, only 41.8% of American medical schools require a preclinical module and 20.5% require a clinical component in this area [6]. We require a preclinical component in the second year, and one of our four major teaching hospitals requires a 2-week orthopaedic clerkship during the clinical years as well. Second, is the way we categorized the examination questions. There are only a few questions for each category and these categories were not individually validated in the same manner as the entire exam, so there may be concern about the reliability of the results. However based on the magnitude of the difference in score between the others category (3rd: 76.9, 4th: 80.1) and back (3rd: 29.2, 4th: 43.4), lower extremity (3rd: 45.4, 4th: 55.7), and upper extremity (3rd: 48.2, 4th: 54.9), and the consistency to which the examination scores of the three region-specific categories are lower than the others category, we believe that there is substantial evidence to draw our conclusion that region-specific musculoskeletal medicine is a specific area of weakness. Third, there are disadvantages from the timing of the administered survey because not all data were collected at the same time for each year, which may raise the question of test reliability. The third-year students were surveyed on completion of their general surgery rotation that offers education in musculoskeletal medicine in the form of an orthopaedic surgery elective. However, as there were no other musculoskeletal electives that students took, we believe biases resulting from surveying students immediately after the surgery rotation would tend to increase third-year students’ examination scores. The fourth-year students took the survey at various times throughout the year because we could only elicit their participation by contacting multiple courses and offering boards review sessions. Some of these students took electives related to musculoskeletal medicine, and the influence of taking these electives was described in a recent study at our institution [12]. Finally, is the question of the reliability of students’ self-reported clinical confidence levels. Caution should be taken when interpreting self-reported clinical confidence as well, because this is not necessarily an accurate reflection of the students’ clinical skill. There also may be intrarater variation if students were asked to report their clinical confidence. Although this cannot be discounted, we believe the confidence levels are still important because we provided a baseline for comparison between the musculoskeletal and pulmonary systems and had students respond to multiple different regions, the results of which would more likely be reliable.

Our data suggest students’ knowledge and clinical skills related to specific anatomic regions may not be adequately addressed. As seen with the competency examination, students performed considerably worse on questions pertaining to the upper extremity, lower extremity, and back compared with other question types, including more systemic conditions such as arthritis, metabolic bone disorders, and cancer. Students’ confidence in performing a physical examination and in generating a differential diagnosis also indicated inadequacy in examining specific musculoskeletal regions because third- and fourth-year students reported below adequate confidence for examining the majority of seven regions. Performance on the examination and reported levels of clinical confidence may not necessarily be linked. Although we were not able to objectively assess the students performing the examination in a clinical setting and so cannot correlate clinical confidence with test competence directly, our analysis revealed little correlation between overall examination scores and overall confidence levels in performing an overall musculoskeletal physical examination (third year, r = 0.248; fourth year, r = 0.140). One possible explanation may be students who have more textbook knowledge may not have much clinical exposure and vice versa.

Compared with third-year students, fourth-year students reported a higher level of confidence in performing a physical examination of the back and in generating a differential diagnosis for the back and knee. Fourth-year students are likely more confident because they took a mandatory 2-week rotation in orthopaedics during their third year (this requirement was turned into an elective for the third-year students in our study as a result of a policy change at our institution). However, why this only made a major improvement for the back and knee is unclear. Possibilities include students had more exposure to particular patient subpopulations or perhaps certain examinations were more thoroughly taught.

The learning gap in musculoskeletal medicine related to specific anatomic regions may be a result of the organization and content of our curriculum. At the time of survey administration, our institution devoted 24 hours (6 days) of instruction and tutorial sessions to musculoskeletal medicine during the second-year musculoskeletal pathophysiology blocks. However, except for a 1-hour lecture on fractures and a 45-minute lecture on bone tumors, no additional time was devoted to orthopaedic medicine. The primary focus of the musculoskeletal block was on rheumatologic and metabolic disorders, which could explain the students’ tendency to perform better on questions in the others category.

One way our institution has begun to address the apparent deficiencies through curricular reform is by adding an orthopaedic block to the second-year human systems pathophysiology course in conjunction with the existing rheumatologic block with each module lasting 4 days. Specific learning objectives pertaining to musculoskeletal conditions of various anatomic regions are incorporated into the 4 days devoted to orthopaedic medicine. To further increase the effectiveness of the musculoskeletal curriculum in this area, second-year students will concurrently learn about the physical examination process of corresponding anatomic regions during the Patient-Doctor II physical examination course. We plan to evaluate the effectiveness of these changes in a continuous effort to improve the musculoskeletal curriculum and also will further refine the curriculum based on education guidelines set by the Association of American Medical Colleges for musculoskeletal medicine [1].

The importance of musculoskeletal medicine in a wide spectrum of clinical fields dictates medical students should be well versed in this subject. However, current literature indicates medical schools are not adequately preparing students in this field [1–3, 7–9, 11]. Our study suggests region-specific musculoskeletal medicine represents a particular area of weakness that may need to be addressed in the undergraduate musculoskeletal curriculum.

References

Association of American Medical Colleges. Contemporary Issues in Medicine: Musculoskeletal Medicine Education. AAMC Medical School Objectives Project, Report VII; 2005. Available at: https://services.aamc.org/Publications/index.cfm?fuseaction=Product.displayForm&prd_id=204&prv_id=245. Accessed November 13, 2007.

Clawson DK, Jackson DW, Ostergaard DJ. It’s past time to reform the musculoskeletal curriculum. Acad Med. 2001;76:709–710.

Day CS, Yeh AC, Franko O, Ramirez M, Krupat E. Musculoskeletal medicine: an assessment of the attitudes and knowledge of medical students at Harvard Medical School. Acad Med. 2007;82:452–457.

De Innocencio J. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal pain in primary care. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:431–434.

De Lorenzo RA, Mayer D, Geehr EC. Analyzing clinical case distributions to improve an emergency medicine clerkship. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:746–751.

DiCaprio MR, Covey A, Bernstein J. Curricular requirements for musculoskeletal medicine in American medical schools. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:565–567.

Freedman KB, Bernstein J. Educational deficiencies in musculoskeletal medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:604–608.

Hing E, Cherry DK, Woodwell DA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2004 summary. Adv Data. 2006;374:1–33.

Matzkin E, Smith EL, Freccero D, Richardson AB. Adequacy of education of musculoskeletal medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:310–314.

Pinney SJ, Regan WD. Educating medical students about musculoskeletal problems: are community needs reflected in the curricula of Canadian medical schools? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1317–1320.

Schmale GA. More evidence of educational inadequacies in musculoskeletal medicine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;437:251–259.

Yeh AC, Franko O, Day CS. Impact of clinical electives and residency interest on medical students’ education in musculoskeletal medicine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:307–315.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

About this article

Cite this article

Day, C.S., Yeh, A.C. Evidence of Educational Inadequacies in Region-specific Musculoskeletal Medicine . Clin Orthop Relat Res 466, 2542–2547 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-008-0379-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-008-0379-0