Abstract

This paper provides a systematic literature review, analysis and discussion of methods that are proposed to practise ethics in research and innovation (R&I). Ethical considerations concerning the impacts of R&I are increasingly important, due to the quickening pace of technological innovation and the ubiquitous use of the outcomes of R&I processes in society. For this reason, several methods for practising ethics have been developed in different fields of R&I. The paper first of all presents a systematic search of academic sources that present and discuss such methods. Secondly, it provides a categorisation of these methods according to three main kinds: (1) ex ante methods, dealing with emerging technologies, (2) intra methods, dealing with technology design, and (3) ex post methods, dealing with ethical analysis of existing technologies. Thirdly, it discusses the methods by considering problems in the way they deal with the uncertainty of technological change, ethical technology design, the identification, analysis and resolving of ethical impacts of technologies and stakeholder participation. The results and discussion of our literature review are valuable for gaining an overview of the state of the art and serve as an outline of a future research agenda of methods for practising ethics in R&I.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This paper provides a review and analysis of literature that deals with methods for practising ethics in research and innovation (R&I). Although a lot has been written on the topic of practising ethics in R&I, no attempt has yet been made to present a comprehensive overview of the myriad of methods that have been proposed to structure and develop it. Next to providing such an overview, this paper offers a critical assessment of the methods and discusses ways to improve them. The notion of practising ethics is used to capture the practices of “doing” ethics in R&I under consideration in their broadest possible sense. However, notions of including, integrating or incorporating ethics in R&I are occasionally referred to as well, when such notions are used in the particular literature that are included in this review.

Practising ethics in R&I may manifest itself in formulations of R&I project-specific codes of conduct or checklists of ethical issues and principles. Also, it can take the shape of ethicists joining in the design process of new technologies and innovations, and of researchers and stakeholdersFootnote 1 engaging with ethical challenges in a collaborative setting. By “methods” for practising ethics in R&I, we mean “detailed, content-specific […] problem solving procedures” (Nickles 1987, p. 104) that aim at structuring the process of practising ethics in R&I. Thus, the methods that are discussed in this paper will commonly present different procedural steps that should be part of practising ethics in R&I. “Methods for practising ethics in R&I” need to be distinguished from methods in conventional research ethics, which belong to a traditional branch of applied ethics that focuses on professional ethics of researchers, including for instance considerations of scientific integrity and treatment of human subjects in experiments. Though the subject matter of traditional research ethics and ethics in R&I show some family resemblance, the fields can be distinguished by their different foci. Whilst traditional research ethics is focused on normative aspects of doing professional scientific research, this paper deals with methods that mostly focus on the ethics of technological innovation and its impacts. Compared to conventional research ethics, which gained momentum after the Second World War with the Nuremberg Code, the academic discussion on methods for practising ethics in R&I commenced only in the 1990s (see Fig. 2 below).

Dealing with ethics in R&I is increasingly urgent because of the transformative potential and complexity of contemporary advancements in science and technology (Brey 2012a, b). Ethical issues in the context of R&I are often multifaceted and pervasive, because they result from complex changes in people’s behaviours, socio-economic relations, power relations between people and institutions, and changes in the environment. For instance, technological innovations grouped under the heading of “ubiquitous computing”, which relate to the growing presence of computational devices connected to the Internet in many aspects of everyday life, are said to be capable of causing harm to inter-human relations and create severe social shifts in economic and political power (Bohn et al. 2005). Another example, in the field of biomedical research, concerns technologies that prolong human life, which evoke ethical questions of the justification of life-prolongation and of fairness in the resulting societal transformations (Kaufman, Shim and Russ 2004). The complexity and ambivalence of ethical issues emerging from the design and outcomes of contemporary R&I call for the development of comprehensive methods that can be used by ethicists, researchers, policy-makers and various other stakeholders (technology users, companies, etc.). These methods can assist in the anticipation or foresight and identification of ethical issues; normative assessment of ethical impacts and participation of the people involved in or affected by R&I processes.

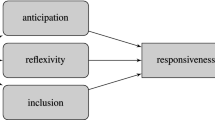

In Europe, in particular, the trend towards the inclusion of practising ethics in R&I projects funded by the European Commission is strongly related to the emergence of the “responsible research and innovation” (RRI) discourse. According to Owen et al., this relatively recent discourse revolves around three features: (1) an emphasis on science for society, discussing the impacts of science, (2) an emphasis on science with society, making R&I responsive to society, and (3) a re-evaluation of the concept of “responsible” as a moral ascription applied to the future-oriented, complex and collective phenomenon of R&I (Owen et al. 2012 p. 757). This is reflected by the notion of “responsible research and innovation”, as it is used in EU institutions, namely as an approach that “implies that societal actors (researchers, citizens, policy makers, businesses, third sector organisations, etc.), work together during the whole research and innovation process in order to better align both the process and its outcomes with the values, needs and expectations of society” (Geoghegan-Quinn 2014).

In order to analyse proposed methods for practising ethics in R&I, a systematic review of the academic literature was conducted to identify methods for practising ethics in R&I. First, the scope and the methodology used to execute our literature searches are discussed. Second, the results of the literature review are presented and an analysis of these results is provided. Third, a structured discussion is presented in which the methods analysed are critically assessed and recommendations for their improvement are proposed.

Scope and Methodology

Even though the literature covered by this paper overlaps with the discourse on RRI and by extension the earlier discourses on “ELSA” (ethical, legal and social aspects) and “ELSI” (ethical, legal and social implications/impacts) (Zwart et al. 2014), its scope is substantially narrower because it only focuses on literature that explicitly and predominantly deals with ethics and not with the broad spectrum of potential impacts of R&I (which might be labelled “social” and “legal” in addition to “ethical”) in general (see Fig. 1). Moreover, it focuses in particular on technological innovations and their role in the R&I process and focuses less on ethical issues in scientific research (e.g. the use of human subjects in genomics research) or on the governance of science and technology.Footnote 2 As Grunwald (2011) argues, RRI brings together applied ethics, technology assessment (TA) as well as science, technology and society studies (STS) research. This literature review overlaps with these fields but always focuses on ethics and excludes foci on for instance policy-advice or descriptive accounts of sociotechnical systems. Considered in relation to STS, this literature review mostly captures what Mitcham characterises as one out of four approaches, which concerns “philosophical and ethical reflections on the essence and meaning of science and technology” (Mitcham 1999, p. 130).

Schematic representation of the scope of the literature review. The literature on methods for practising ethics in R&I falls within the ELSA/ELSI/RRI discourse and is situated on the intersection of the fields of applied ethics as a sub branch of philosophy, STS, foresight studies and technology assessment

In order to obtain a broad overview of existing methods for practising ethics in the context of R&I, three major databases for scientific literature were consulted: Web of KnowledgeFootnote 3 (containing major scientific databases such as Web of Science, BIOSIS, MEDLINE and SciELO Citation Index), ScopusFootnote 4 (including major scientific databases such as Elsevier, Wiley-Blackwell and IEEE) and the Springerlink database.Footnote 5 Seven search terms were selected by considering the most common concepts that are used in the literature to refer to practising ethics in R&I. Since the wordings that are closer to this paper’s characterisation of this thematic, namely “practising ethics” and “incorporating ethics” did not deliver many valuable results, the term “assessment” in combination with “ethics”, “ethical”, “technology” and “impacts” was used, as the practice of ethics in the fields of applied ethics and ethics of technology is mostly referred to as “assessment” and sometimes as “evaluation”. Additionally, three search terms were formulated to ensure that the literature selection is properly embedded in the ELSA, ELSI and RRI discourses, using these three terms explicitly in conjunction with the wordings “method” “research” and “innovation”. Only literature in written in English has been included in the literature selection, which probably will have led to the exclusion of a number of interesting sources on methods for practicing ethics in R&I in other languages. Table 1 shows the total number of sources identified in each database for each particular query. Ten different searches in each database resulted in a total of 2626 hits (including duplicates).

The second selection of the literature was made manually according to three necessary conditions: the titles and abstracts of the available sources were scanned for the presence of the aspects of (1) ethics in an (2) R&I context, clearly mentioning or discussing (3) methods or approaches to practice ethics in R&I. The results of this selection are displayed in Table 1 under the headings “useful results”. Certain sources, such as those explicitly focusing on methods for practising ethics in science education, on practising ethics in the context of clinical practice or discussing the practice of ethics in management or organisational contexts, however interesting, were omitted from the secondary selection results because of their lack of connection with R&I. Eventually, a total number of 107 useful sources was arrived at, which after a check for duplicates was reduced to 73 unique useful sources.

A third selection of the literature was made according to the backwards-snowballing method (Wohlin 2014), looking at the reference lists of all useful sources found in the literature searches. During this snowballing process, sources were selected according to two criteria concerning the references: (1) their titles should explicitly mention the terms “ethics” or closely related terms (e.g., “ethical”, “moral”) and at least one of the terms “research”, “innovation” or “technology” or (2) their titles should mention a specific methodology found in the earlier selection.Footnote 6 After this snowballing process, 63 additional sourcesFootnote 7 were selected, which gave a total of 136 useful sources.

Results

In this section, the results of the literature review are presented by considering (1) the distribution of the sources across different fields, and by (2) classifying and analysing the main traits of these methods.

The literature selection shows that the academic discussion on practising ethics in R&I commenced relatively recently, in the 1990s, and has gained considerable momentum in the last 10 years (see Fig. 2). The literature also shows that ethics in the context of R&I is gaining in importance (Fig. 2).

Number of sources published in five-year intervals, between 1990 and 2015. The last interval is not fully representative, because the literature searches were conducted in October 2015. It could therefore be the case that more relevant sources were published after the literature searches in 2015 that are not taken into account in this overview. One search was conducted in 2017 (using the query “research and innovation” AND “method”). However, for the sake of consistency the results were filtered for sources that were published before November 2015

Practising Ethics in Different Fields of R&I

Most of the sources that were selected do not discuss general methods for practising ethics in R&I, but focus on specific fields in which R&I processes take place. The following table provides an overview of the distribution of the different fields discussed in the selected literature (Table 2):

It can be observed that of the disciplinary fields of R&I, the field of health technologies is the most represented in the literature, followed by the fields of information systems research and computer science. The considerable number of sources that belong to these fields in comparison to, for example, organisational studies can be explained by the fact that technological innovation is the core focus of these fields.

R&I in the context of health technologies has traditionally been ethically sensitive because it deals with technologies that aim at assisting patients and vulnerable groups such as disabled and elderly people. This would explain its prominent position in the literature selected. Most discussions about ethics in the field of health technologies focus on the perceived need to increase the role of ethics in the broader practice of health technology assessment (HTA) (Braunack-Mayer 2006; DeJean et al. 2009; Ten Have 1995, 2014; Hofmann 2008; Lehoux and Williams-Jones 2007) and on the articulation of criteria that should inform methods for practising ethics in HTA (Arellano et al. 2011; Burls et al. 2011; Duthie and Bond 2011; Grunwald 2004; Potter et al. 2008; Saarni et al. 2011; Sandman and Heintz 2014). Importantly, though, discussions also focus on the perceived lack of clear methodological guidance for practising ethics in the field of HTA as it currently stands (Autti-Ramo and Makela 2007; Burls et al. 2011; Hofmann 2014). Ashcroft even questions the ability of the field of HTA to address ethical issues altogether, because of its focus on technical questions rather than on evaluative ones (Ashcroft 1999).

As yet (2015), the selected sources discussing ethics in the field of health technologies do not show signs of widely used methods. The methods that were found for practising ethics proposed in the health technology literature are “checklist”-based methods (Heintz et al. 2015; Hofmann 2005b), a “value analysis” that seems to be closely related to the value sensitive design approach (Hofmann 2005a), a “rapid ethical assessment” method (Addissie et al. 2014), an approach according to which stakeholder participation can be organised (Autti-Ramo and Makela 2007), a bibliometric method for conducting desk research of ethical issues in HTA (Droste et al. 2010), an “interactive technology assessment” approach that combines TA approaches with stakeholder engagement (Van der Wilt et al. 2015), a revised version of the “Socratic approach” (Hofmann et al. 2014) and an “triangular” approach that proposes to organise the practising ethics according to concrete steps, based on the principlism method that originates from biomedical ethics (Sacchini et al. 2009). None of these proposed methods seems to be (as of 2015) adopted by the health technologies field in a broad fashion.

In contrast to the field of health technologies, the fields of information systems research and computer science seem to have produced and seem to use more generally established methods for practising ethics, since several methods are discussed and developed in multiple sources by different authors. Notable examples of these are the ETHICS method (Adman and Warren 2000; Arellano et al. 2011; Hirschheim and Klein 1994; Leitch and Warren 2010; Mumford 1995; Singh et al. 2007; Wong and Tate 1994), the Value Sensitive Design (VSD) method (Friedman 1996; Friedman et al. 2006; Manders-Huits and Van den Hoven 2009; Shilton 2014; Van den Hoven 2007, 2008; Van den Hoven and Manders-Huits 2009; Le Dantec et al. 2009), the ETICA approach (Stahl 2011, 2013; Stahl et al. 2010; Wakunuma and Stahl 2014), the discourse ethics method (Rehg 2015; Mingers and Walsham 2010; Mittelstadt et al. 2015), the disclosive ethics approach (Brey 2000; Light and McGrath 2010), an ethical impact assessment approach that focuses on stakeholder consultation (Wright 2010; 2011; Bailey et al. 2013), human-driven design (Ikonen et al. 2012; Niemela et al. 2014) and a checklist approach (Van Gorp 2009). Some sources in these fields discuss the general need for practising ethics, and criteria for designing methods to do so (Brey 2012a; Carew and Stapleton 2013; Carpenter and Dittrich 2013; Van Gorp 2009; Tavani 2013), and how ethical analyses could add to the general success of ICT projects (Stapleton 2008). Markus and Mentzer (2014) discuss particular methodologies for conducting foresight studies, which could be integrated in an approach for practising ethics (such as the Delphi method, anticipatory technology ethics and sociotechnical transition analysis). Sassaman (2010) discusses specific ethical issues for computer security research, but without applying a distinct methodology.

Methods discussed in the field of nanotechnologies are the network approach and the impact and acceptability analysis method (Patenaude et al. 2015; van de Poel 2008). Also, the organisation of interviews with nanotechnology researchers is discussed to show how ethical issues are incorporated in their work (Viseu and Maguire 2012). The ethical matrix is widely used in agricultural and environmental R&I (Boucher and Gouch 2012; Bruijnis et al. 2015; Heleski and Anthony 2012; Kaiser et al. 2007; Whiting 2004). Sources that consider ethics in the engineering sciences mostly focus on professional ethics for engineers: on how engineers should work in order to foster a practice of responsible engineering in R&I (Grunwald 2001; Herkert 2001; Riley 2013; Verharen et al. 2013; Whitbeck 2011). Methods used in the engineering sciences are the VSD method (van Wynsberghe and Robbins 2013) and a scenario approach dealing with science-fiction narratives of technological prototypes (Stahl et al. 2014). In other, less well-represented fields, sources discuss the perceived need for practising ethics (for operations research) and criteria for doing so (Brans 2004) as well as ways for practising professional ethics, notably in business settings (Bose 2012; Fassin 2000; Polonsky 1998; Schumacher and Wasieleski 2013). An embedded researcher approach (Reiter-Theil 2004) and checklist approaches are used in the biomedical sciences (Winkler et al. 2011), an application of just war theory (Malsch 2013) and a “metric of evil” method in military R&I (Reed and Jones 2013), care ethics integrated in VSD in R&I in healthcare settings (Van Wynsberghe 2013) and a stakeholder framework in operations research (Drake et al. 2009).

A considerable share of our selected sources does not deal with any particular field of R&I, but rather with technology design and development or ethics of technology in general (see e.g. Bitay et al. 2005). Some sources especially focus on explicating the need to have methods for practising ethics in R&I and formulating concrete steps and criteria that should be part of such methods (Decker 2004; Palm and Hansson 2006; Skorupinski and Ott 2002; Swierstra and Rip 2007). Some of these sources especially focus on dealing with uncertainty when dealing with emerging technologies (Lucivero et al. 2011; Rommetveit et al. 2013; Sollie 2007) and the effects of practising ethics on R&I practices (Graffigna et al. 2010). Sources also present and discuss specific methods for practising ethics in R&I, such as codes of ethics or checklist approaches (Verharen and Tharakan 2010), VSD, the ethical impact assessment (EIA) method (Wright 2011, 2014; Wright and Friedewald 2013), ethical scenario methods (Boenink et al. 2010; Ikonen et al. 2012; Ikonen and Kaasinen 2008; Wright et al. 2014), the network approach (Zwart et al. 2006), the ethical matrix approach (Forsberg 2004, 2007; Mepham et al. 2006), the human practices (HP) approach (Balmer and Bulpin 2013), the anticipatory technology ethics (ATE) method (Brey 2012a, b), pro-ethical design (Floridi 2015), the walkshop approach (Wickson et al. 2015) and the technological mediation approach (Verbeek 2006). Some sources also critically assess the general role of ethics in R&I processes (Grunwald 2000), focusing for instance on the difficulty of making epistemic claims about future impacts of R&I processes (Mittelstadt et al. 2015) and the difficulty of reconciling the assessment of a certain vision of future outputs of R&I processes with the idea of a person’s future (Karafyllis 2009).

A number of sources explicitly criticise methods for practising ethics, providing criticisms of the principlism approach or principled approaches in general (Groves 2015; Page 2012; Ten Have 2014), the ethical matrix (Cotton 2009; Jensen et al. 2011; Mepham 2000; Schroeder and Palmer 2003), VSD (Borning and Muller 2012) checklist approaches (Masclet and Goujon 2012; Roberts 1999), the ETHICS method (Stahl 2007), the ETICA method (Rainey and Goujon 2011) and the methodologies of specific R&I projects focussing on ethics (Thorstensen 2014). Finally, sources contain discussions comparing different methods (Beekman and Brom 2007; Doorn 2012; Ferrari 2010; Flipse et al. 2013; Forsberg et al. 2014; Gamborg 2002; Hummels and de Leede 2000; Lindfelt and Tornroos 2006; Markus and Mentzer 2014; Wickson and Forsberg 2014) and discussions about the effects of practising ethics on research professionals and on the R&I process (Foley et al. 2012; Schummer 2004).

Analysis of Methods for Practising Ethics in R&I

35 different methods for practising ethics in R&I were found in the selected sources, which were categorised according to their position with regards to the “R&I process”. Several authors propose different characterisations of the R&I process (see, e.g., Roberts 2007; Hauser et al. 2006; Kajikawa et al. 2008). Though they differ on certain points, they generally conceptualise the R&I process as a process (1) based on conceptual (scientific) knowledge that (2) translates a certain conceptual idea into a technological design that is tested, prototyped and translated into an actual application, which (3) can subsequently be put into production and introduced to society at large. An R&I process can therefore be conceptualised in terms of these three stages. Even though the methods generally focus on different parts of the R&I process, they commonly position themselves according to these three stages.

We refer to these positions as “ex ante”, which means that a method aims at practising ethics at the early stage of the R&I process, “intra”, which means that a method aims at practising ethics during the design and testing stage of the R&I process and “ex post”, which means that methods aim at practising ethics at the stage when an R&I process is already finished and has resulted in concrete applications.Footnote 8 The table below provides an overview of the methods, mapped according to their characterisation as ex ante, intra and ex post and according to their sub-aims (which are explained below). It must be noted that not each method fits perfectly in one of the three categories (e.g. discourse ethics can also be used for ex post analyses), but that when considering their general foci and their novelty the categories provide a useful heuristic for typifying the methods. In this section, the methods will be analysed by elucidating certain procedural steps that are common for each stage (ex ante, intra and ex post) of the R&I process. For each general type of method (1) the targeted users,Footnote 9 (2) the over-arching aim and (3) typical procedural steps proposed (relating to the “who”, “why” and “what” aspects of the methods) for the sub-aims of each main method-type will be discussed. The procedural steps will be illustrated by highlighting some of the methods (Table 3).

Ex ante Methods

Ex ante methods position themselves in such a way that they try to organise practising ethics at the start of an R&I process, when the R&I activities have not yet been translated into any concrete design or application. These methods are therefore much concerned with “emerging technologies”, the ethical impacts of which still lie in the future and can therefore only be “anticipated” or “foreseen”. For this reason, ex ante methods often propose or include foresight approaches or other methods that construct scenarios to delineate ethical issues and/or desirable or undesirable futures that have been impacted by the ethical issues or their resolution. Most of the ex ante methods belong to a unified body of literature; except for the methods that are grouped under “scenario approaches”. Scenario approaches are proposed under different headings (e.g. techno-ethical scenarios, ethical dilemma scenarios) by different authors, but because they roughly share a common aim and structure they are grouped under a single heading. Ex ante methods mostly target ethicists and RRI or foresight specialists and thereby are typically expert-focused. Exceptions are the eTA method, which includes technology developers (Palm and Hansson 2006, p. 555), Rehg’s version of discourse ethics, which includes policy makers and a variety of stakeholders (Rehg 2015, p. 38),Footnote 10 Ikonen and Kaasinen’s (2008) version of a scenario approach and the ethical impact and accessibility analysis, which included a variety of actors (Patenaude et al. 2015). However, mechanisms for involving different stakeholders are scarcely discussed in ex ante methods.

The overarching aim of ex ante methods is to deal with the dilemma of uncertainty of technological change that results from “new” and “emerging” technologies. Sources belonging to five out of the eight ex ante methods refer to the Collingridge control dilemma, which stipulates that controlling a technology is difficult due to (1) the lack of knowledge about harmful impacts of a technology during the early stages of its development and (2) the difficulty of changing a technology once it has been embedded and stabilised in a society (Sollie 2007, p. 297). Responding to this dilemma therefore provides the overall rationale for ex ante methods. A related issue that ex ante methods typically address is the interconnection between technological change and morality: technological change implies a change in morality and vice versa (Boenink et al. 2010, p. 9). The sub-aims of ex ante methods can be characterised as follows: (1) to identify emerging technologies (e.g. the ETICA approach), (2) to understand possible future ethical impacts (e.g. scenario approaches), (3) to ethically evaluate emerging technologies (e.g. the ATE method) and (4) to critically assess the status of normative claims concerning ethical issues of emerging technologies (e.g. the discourse ethics method).

Procedural Steps of Ex Ante Methods

-

Ex ante methods propose steps to identify potential emerging technologies. The ETICA project provides a good illustration of such procedural steps (Stahl 2011; Stahl et al. 2010). First, it performs a foresight analysis to identify emerging technologies by capturing the current discourse on future ICTs, which entails a discourse analysis of documents issued by governments, research institutes and companies about expected impacts of emerging technologies. This review is condensed in “meta-vignettes”, which contain data about the emerging technologies, applications and artefacts (their defining features, related ethical issues, etc.). Second, the approach includes a bibliometric analysis that comprises a large amount of scholarly work to show which ethical concepts are used in relation to which (emerging) technology.

-

Ex ante methods propose steps to construct scenarios about future ethical impacts. Scenarios are considered powerful tools for thinking about the future help understanding future ethical impacts of emerging technologies. The techno-ethical scenarios approach offers a good illustration of related procedural steps (Boenink et al. 2010). It proposes three steps: (1) a thorough analysis of the point of departure of the relevant ‘moral landscape’, (2) the introduction of technological development and an imaginary sketch of its interaction with the moral landscape and (3) the closure of moral controversies that had arisen due to the interaction in (2).

-

Ex ante methods propose steps to evaluate potential ethical impacts. Impacts can be evaluated by offering a heuristic of ethical principles, such as is proposed by the eTA method. The ATE method (Brey 2012a) is a good illustration of the embedding of such a heuristic in a conceptual understanding of emerging technologies. It distinguishes three levels of ethical analysis: (1) analysis of the technology (collection of techniques related to a common purpose or domain), (2) analysis of the artefact (functional systems, artefacts and procedures based on a technology) and (3) analysis of the application level (the specific way in which artefacts are configured to be used). The ATE postulates an identification stage at which ethical impacts are identified and descriptions of a technology (at the three levels mentioned above) are analysed by means of a list of ethical values and principles. Brey proposes an evaluation stage, during which the relative importance of ethical impacts is assessed along with their likelihood of occurring.

-

Ex ante methods propose steps to assess the status of uncertain normative claim. This assessment deals with the problem that claims about the future have a different epistemic status than claims about the past or present. The discourse method offers a good illustration of relevant steps that can be taken. The method of discourse ethics draws strongly from the work of Habermas (1990) and Apel (1980) and was firstly introduced to practise ethics in ICT R&I by Rehg (2015). It is based on two basic principles: the discourse and the universality principle (Mittelstadt et al. 2015, p. 1037). The discourse principle states that only those norms that could meet with the approval of all affected in their capacity as participants in a practical discourse could have a claim to validity. The universality principle states that the (unforeseen) consequences of adherence to a norm should be acceptable to all involved stakeholders (ibid.). The application of discourse ethics to ethical analysis of emerging technologies stipulates the following steps: (1) claims are broken down into constitutive parts, (2) uncertain claims about the future are assessed according to empirical evidence and general indicators about the future and (3) the normative position that relies on the uncertain claim is assessed for acceptability amongst relevant stakeholders.

Intra Methods

Intra methods position themselves to practise ethics at the stage of an R&I in which conceptual ideas are being translated into a concrete technology design, and in which prototypes are made and tested. Methods focusing on this stage of the R&I process commonly deal with the translation of ethical values into design requirements and with the formulation of concrete design steps. Intra methods focus on three main groups of targeted users: (1) ethicists, mainly for disclosing ethical issues in design, determining how values can be embedded in design or understanding how they can partake in the R&I process, (2) policy makers, mainly for being able to organise the process of practising ethics in an R&I context and (3) researchers and designers, mainly for being able to integrally address ethical issues in the process of technology design.

The over-arching aim of intra methods is to enable, organise and ensure ethical technology design. They commonly refer to particular examples of ethical issues related to technology design, such as care robots affecting a patient’s autonomy (Van Wynsberghe 2013, p. 409), social network services affecting the privacy of their users (Wright 2011, p. 199) and the impact of cell phones on human communication and interaction (Verbeek 2006, p. 2), to provide a rationale for their existence. The sub-aims of intra methods can be characterised as follows: (1) to disclose ethical issues in design (e.g. disclosive ethics), (2) to stipulate how values can be embedded in technology design (e.g. VSD), (3) to organise the process of “practising ethics” in the technology-development pipeline (e.g. EIA) and to make sure ethicists can work integrally in R&I projects, to be as “close” to the R&I process as possible (e.g. parallel researcher approach).

Procedural Steps of Intra Methods

-

Intra methods propose steps to integrate ethicists in the R&I context. This should bring ethicists closer to the everyday reality of R&I practitioners. The parallel researcher approach offers a good illustration of related procedural steps (Van Gorp and Van der Molen 2011). It proposes five steps: (1) gathering information about an R&I project, (2) reflecting on resulting ethical issues and search for relevant literature, (3) prepare a discussion with R&I practitioners about the ethical issues and possible ways to mitigate these issues, (4) have the discussion and take decisions and (5) report about the ethical issues and the decisions made during the discussion.

-

Intra methods propose steps to disclose ethical issues in technology design. The main issue that is addressed is at what point during the design process ethical issues are disclosed, and how they are disclosed. The disclosive ethics approach provides a pertinent illustration of related procedural steps. Brey stipulates two stages of ethical analysis: (1) the analysis of a technology on the basis of a moral value and (2) the use of a theory to formulate guidelines for the design process. Tavani discusses the three levels in the R&I process at which ethical analysis takes place: the disclosure level, at which ethical issues are identified, the theoretical level at which moral theory is developed and the application level, at which findings from moral theory are applied to the issues identified in the disclosure level (Tavani 2013, p. 26). The disclosive ethics approach stipulates that practising ethics in R&I should be a multidisciplinary exercise, because the knowledge of researchers is needed as input at the disclosure level while the knowledge of ethicists is explicitly needed at the theoretical level.

-

Intra methods propose steps to embed values in technology design. This is proposed to ensure that human values are taken into account during the design process, instead of post hoc when reflecting on a completed technology design. VSD offers a good illustration of related procedural steps (Friedman et al. 2006). At the centre of VSD is a “tripartite” methodology that sets out three stages of investigations that aim at stipulating how human values can be embedded in technology design. The first (1) of these stages is the conceptual stage in which working conceptualisations of relevant human values are proposed and basic questions are answered, e.g., about the relevant stakeholders. The second (2) stage is the empirical one, in which social science methods (qualitative and quantitative) are used to gather empirical data about embedding values in technology design, for instance, by looking at how stakeholders consider certain values in a use-context. The third stage (3) is the technical stage during which researchers investigate how technical properties of technologies both hinder and promote human values.

-

Intra methods propose steps to organise “practising ethics” in the design process. This effort focuses on the governance of ethics in an R&I context, prescribing what it should contribute at which stage of the R&I process. The EIA method provides a fitting illustration of procedural steps (Wright 2011). It presents a list of 15 steps that should be part of an EIA, namely, (1) to determine whether an EIA is needed, (2) to identify the team of assessors and its terms of reference, (3) to prepare an EIA plan, (4) to describe the process to be assessed, (5) to identify the stakeholders, (6) to analyse the ethical impacts, (7) to consult with stakeholders, (8) to check whether the R&I project complies with regulations, (9) to identify risks and possible solutions, (10) to formulate recommendations, (11) to prepare and publish an EIA report, (12) to implement the recommendations, (13) to organise a (third-party) review and audit of the EIA, (14) to update the EIA if changes in the R&I project occur and (15) to ensure ethical awareness throughout the organisation conducting the R&I project (Wright and Friedewald 2013, p. 763).

Ex Post Methods

Ex post methods are concerned with what is often characterised as “analysing ethical issues” of technologies that already exist, as outcomes of R&I processes. These methods therefore mostly engage in retrospective ethical reflections that take known ethical issues of known technologies as their subject (such as privacy issues arising from the use of social media). Ex post methods predominantly target experts, which can be ethicists, institutional bodies (e.g. government agencies focusing on ethics), expert groups or specific R&I professionals. Some methods focus on the general public (any type of relevant stakeholder), such as the ethical matrix.

The over-arching aim of ex post methods is to identify, analyse and revolve ethical impacts of technologies. These methods commonly refer to dilemmas faced by R&I practitioners to consider ethical issues in their work, for instance by members of the “network on appropriate technology” (Verharen and Tharakan 2010, p. 36), modellers in operation research (Drake et al. 2009) and corporate governance practitioners (Schumacher and Wasieleski 2013), as a rationale for their existence. Additionally, they refer to the integral role of ethics in a respective R&I context (Heintz et al. 2015) and to the need to democratise the ethical assessment of technologies (Mepham 2000). The sub-aims of ex post methods can be characterised as follows: (1) to identify ethical impacts related to technologies (e.g. the human practices approach), (2) to analyse ethical impacts (e.g. the ethical matrix), (3) to organise the ethical analysis of technologies from a governance or compliance perspective (e.g. the ethic-innovation approach) and (4) to support ethical decision-making with technology (concerning technologies in use) (e.g. the metric of evil).

Procedural Steps of Ex Post Methods

-

Ex post methods propose steps to identify ethical issues raised by existing technologies. The focus here lies on providing heuristics for practitioners to explore ethical issues in their work. Checklist approaches are perhaps the best illustration in this context, because they are widely used in practical settings. Even though they don’t form a singular, coherent method, they can be grouped under one heading because of their common structure and purpose. A checklist approach can consist of a list of “items”, such as “flourishing” or “freedom” (Verharen and Tharakan 2010, p. 39), a list of questions such as “are their moral challenges related to components of the technology?” (Burls et al. 2011, p. 233), or a list of ethical issues such as “safety” and “sustainability” (Van Gorp 2009, p. 36).

-

Ex post methods propose steps to analyse ethical issues raised by existing technologies. Analysis of ethical issues is commonly based on a heuristic of ethical principles, in combination for instance with a list of stakeholders. The ethical matrix is a congruous illustration of this. It makes use of the principlism approach of Beauchamp and Childress (2001) by providing principles that are guidelines for the evaluation of R&I outcomes. It depicts the principles in a visual matrix on one axis and different relevant stakeholders on the second axis. In each cell of the matrix, assessors can reason how a certain principle might be either infringed upon or promoted by a certain R&I outcome, depending on the respective stakeholder (Mepham 2000, p. 171).

-

Ex post methods propose steps to organise the governance of ethical analyses. In this context, the focus lies to some extend on “compliance”, on determining whether R&I processes comply with certain ethical standards. A demonstrative illustration of this is the ethic-innovation method, which stipulates four stages in the governance of ethical analyses in commercial contexts (Schumacher and Wasieleski 2013, p. 27). The first stage revolves around determining the time horizon of the relevant decision makers. The second stage aims to determine the degree of ethical sensitivity. The third stage provides steps to integrate ethics in a company’s value system, goals-set, strategic decisions and business models. The fourth step characterises innovation decisions that take ethical values into account.

-

Ex post methods propose steps to support ethical decision-making with existing technology. Currently, this seems to be an increasing area of interest with for instance the advent of self-driving cars that need “ethical” decision-making systems. The “metric of evil” proposed in the context of military research provides a pertinent illustration of related procedural steps (Reed and Jones 2013). It revolves around designing an “equation” for determining the potential evil for an action in a military context. This requires the identification of the potential consequences of actions, determining parameters that capture the feature of a baseline moral system, calibrate parameter values using expert consultation and incremental adjustment of parameter weightings.

Discussion

In this section, a number of problems of the methods are discussed and recommendations for improvements are presented. The discussion is structured by considering the over-arching aims of the three types of methods that were analysed (ex ante, intra, ex post) and one common challenge that all methods have to deal with, concerning the appropriate participation of stakeholders. For each aim, problems in the methods to deal with it are discussed and recommendations towards the solving of these problems are put forward. The discussion is based on two types of input: (1) from the sources in the literature selection that critically discuss a specific challenge (or a related method), (2) from auxiliary sources in the literature on philosophy, applied ethics, RRI, STS, foresight studies and technology assessment that offer additional relevant insights. An important limitation of the discussion is that it does not provide a comprehensive overview of all the problems in the methods for practising ethics in R&I and all possible ways to deal with these problems. Rather, it presents a tentative overview of some of the key problems that were encountered in the literature and some suggestions for dealing with these problems.

Uncertainty of Technological Change

The over-arching aim of ex ante methods is dealing with the uncertainty in R&I processes, especially pertaining to the ethical reflection on emerging technologies. The methods that were analysed deal with uncertainty differently: by means of scenario building, foresight methodologies, bibliographical analysis and customised heuristics. Two main problems related to these approaches were identified.

First, the aspect of speculation in future-oriented ethical frameworks constitutes a problem. As Nordmann argues, speculation about the future or about the “if and then” should be rejected from a philosophical point of view, amongst other alternatives for the reason that it is impossible for us “to imagine ourselves as something other than we are” (Nordmann 2007, p. 41). Procedural approaches such as discourse ethics and the ethics of uncertainty to some extent deal with this issue by offering ways to assess uncertain claims, but they don’t stipulate what type of claims one should be looking for in a discourse about emerging technologies. Lucivero et al. argue along similar lines as does Nordmann, and they contend that one ought to look into the structure of present expectations or promises (a reflection on the present) rather than to speculate about future impacts (Lucivero et al. 2011). As Borup et al. explain, “expectations play a central role in science and technology not least because they mediate across boundaries between different scales, levels, times and communities” (Borup et al. 2006, p. 289). Expectations could for instance be understood along the lines of “future imaginaries” constructed by actors dealing with emerging technologies (Groves 2013).

Second, a problem arises out of the implicit assumption in the methods that were analysed: that one can arrive at a situation in which one has gained sufficient knowledge about the future to stipulate procedures for action or guidance in R&I processes. As Markus and Mentzer argue, “the attempt to anticipate future conditions is frequently frustrated by unpredictable technological and social discontinuities” (Markus and Mentzer 2014, p. 363). Similarly, Vallor argues that emerging technologies bring about “acute technosocial opacity”, meaning an uncertainty that comes with the growing complexity and ubiquity of technologies that play a role in our everyday lives (Vallor 2016, p. 6). She argues against the idea that the consequences of emerging technologies can always be meaningfully predicted, and instead claims that ethics of emerging technologies should not merely focus on action-guidance based on foresight but also on the cultivation of virtuous character. According to this approach, one should also aim to cultivate ones abilities to predict and cope with unforeseen consequences, rather than only trying to formulate predictions that offer ground for action-guidance. Pandza and Ellwood offer a good illustration for the relevance of virtue ethics when considering the issue of uncertainty, by showing how cultivation of virtues of R&I practitioners assists them in dealing with responsibility in situations of high uncertainty (Pandza and Ellwood 2013).

Recommendations

-

Methods for practising ethics in R&I that make use of methodological constructs to imagine or foresee possible futures pertaining to the development and use of emerging technologies should more thoroughly engage in an epistemological discussion of the limits of knowledge pertaining to such foresight.

-

Whenever future development and use of emerging technologies cannot be meaningfully foreseen, methods for practising ethics in R&I should take appropriate approaches into account that divert from action-guidance based on speculative knowledge about the future such as approaches for the analysis of present promises and expectations concerning emerging technologies and approaches in virtue ethics.

Ethical Technology Design

The over-arching aim of intra methods is enabling, organising and ensuring ethical technology design. The methods that were analysed offer different, complementary ways of dealing with this: by integrating ethicists in R&I practises, identifying ethical issues in design, embedding values in design and organising ethical design in the R&I process. Two key problems in these approaches were identified.

First, next to integrating ethicists in the R&I process, as is suggested by some of the approaches (e.g. the embedded researcher approach), researchers should be able to integrate ethics in their work. As Brey argues, the knowledge of researchers is pivotal for disclosing ethical issues in design for their knowledge about the design and its potential usually substantially surpasses that of the ethicist working in R&I projects (Brey 2000). Borning and Muller acknowledge this issue when stressing that the VSD approach should make “clearer the voice of the researcher” (Borning and Muller 2012, p. 1125). Along similar lines, Le Dantec et al. argue that VSD offers “inadequate guidance on empirical tools” (Le Dantec et al. 2009, p. 1141) and additionally suggest that the empirical investigation should be given priority in VSD and related approaches. VSD is primarily considered here, but this issue seems to persist in the other methods for ethical technology design for none of them offers a way for R&I practitioners to integrate ethics in their work. An exception might be the ETHICS approach, which seems more accessible to R&I practitioners and much more closely relates to their day-to-day reality (at least in the context of information systems R&I). However, the ETHICS approach suffers from another weakness, namely that it lacks an ethical foundation, which makes it difficult to argue that the design choices resulting from the use of the ETHICS method can also be justified as ethical choices (Stahl 2007).

Second, the notion of embedding values in design as it is pragmatically used in approaches dealing with ethical technology design is insufficiently theoretically supported. As Van de Poel (2013) for instance explains, the translation of values into design requirements—the “how” of values in design—is not adequately dealt with. In line with this critique, Manders-Huits argues that the concept of “values” in VSD and their realisation is left undetermined (Manders-Huits 2011, p. 271). Also, Albrechtslund argues that VSD and related approaches insufficiently deal with the difference between designer’s intentions and users’ practice (Albrechtslund 2007, p. 63). All these concerns seem to focus around a lack of theoretical grounding of how values can be embedded in technology design, or how technology design mediates certain values. Not only VSD has to deal with this problem, but also other methods dealing with embedding values in design such as the triangular model, value analysis and human-driven design. Possible ways to deal with this issue are the introduction a value hierarchy, as argued by Van de Poel (2013), but more sources seem to point at a more thorough interaction between methods dealing with ethical technology design and theories in STS and philosophy of technology. For instance, Manders-Huits (2011) mentions Winner’s account of a technological arrangement mediating political values (Winner 1980), Verbeek (2008) mentions Latour’s notion of technical mediation through programs of action (Latour 1994) and Albrechtslund (2007) and Spahn (2015) mention the notion of technological mediation in Ihde (1990) and Verbeek (2005) as entry points for integrating the understanding of values embedded in design with technological mediation.

Recommendations

-

Approaches dealing with ethical technology design should focus more on the integration of ethics in the day-to-day work of R&I practitioners, especially with regards to the disclosure of ethical issues in design.

-

Considerations of methodological aspects of ethical technology design should be based on a normative theoretical framework that explicates how certain technology design choices can be identified as ethical, or how “ethics” is mediated by technology design.

Identifying, Analysing and Resolving Ethical Impacts

The over-arching aim of ex post methods is to identify, analyse and resolve the ethical impacts of developed technologies. They deal with these aspects by offering heuristics such as checklists, analytic frameworks and ethical decision-making procedures. Two key problems in these approaches were identified.

First, a general problem that arises from many of the established methods is the problem of value conflicts (conflicts between different ethical principles that apply). For instance, the ethical principles of security and privacy might conflict in an ethical analysis of cyber security technologies. Principled or checklist-based approaches based on ethical principles can create such normative conflicts or at least questions since they do not include a hierarchy or lexical order that could help to decide which principle or moral value is to be prioritised. As Schroeder and Palmer argue, the widely used ethical matrix is inadequate in terms of “weighing the ethical problems that it uncovers” (Schroeder and Palmer 2003, p. 295). Moreover, Cotton argues that the approach could instigate “potential conflict among stakeholders” (Cotton 2009, p. 164). The problems should not be uniquely attributed to the ethical matrix, but apply to all methods offering heuristics for the identification and analysis of ethical impacts without the provision of methods for dealing with value conflicts. The pragmatic NEST-ethics (Swierstra and Rip 2007) approach offers a way to deal with this problem, by focusing on the argumentative patterns around an ethical controversy instead of on the ethical-decision making process. However, this approach has the disadvantage that it focuses merely on description and prediction and insufficiently offers a normative, prescriptive perspective (Brey 2012b). From this, one can concede that if a method for an ethical analysis of technology includes multiple values, a well-grounded and justified order of those values should be provided. For instance, decision criteria for resolving value conflicts could be provided (Wenstøp and Koppang 2009).

Second, ex post methods offer inadequate guidance on how to choose between sociotechnical alternatives or courses of action based on an ethical analysis. Arguably, this issue is relevant for both intra and ex post methods, though technologies need to have been developed to a significant extend to meaningfully consider choices of sociotechnical alternatives. As Markus and Mentzer argue, an important limitation of literature dealing with the analysis of ethical impacts of technologies is that it “offers little guidance on how to identify the sociotechnical alternatives that should be compared for their ethical consequences” (Markus and Mentzer 2014, p. 359). Related to this, Page argues that the heuristics used for ethical analyses, such as lists of ethical principles, do not by themselves lead to adequate decision-making when R&I practitioners are confronted with different alternatives (Page 2012). A way to deal with this problem is by engaging with multiple criteria design analysis (Van de Poel 2009). As Van Gorp indicates, ethical issues can be related to actions in the design process by considering the “operationalization of technical requirements and the making of trade-offs” (Van Gorp 2005, p. 154). Another approach suggested by Cotton is a deliberative ethical procedure that focuses on problem framing, option scoping, criteria elicitation, and option appraisal (Cotton 2009, p. 167). When considering the actual of practising ethics on R&I practise, Shilton proposes an interesting model for determining when an intervention in the R&I process can be considered successful (Shilton 2014).

Recommendation

-

Researchers and assessors should use a convincing methodological solution for the problem of value conflicts, when they occur. This could be done by including procedures for reasoned balancing of ethics principles whenever no fixed and justified ranking of principles is provided.

-

Methods that analyse ethical impacts of technologies should offer procedural guidance that would allow for using the analysis to choose between certain sociotechnical alternatives.

A Common Challenge: Appropriate Participation of Stakeholders

A challenge that presents itself across the main method-types concerns the appropriate identification and participation of stakeholders in the process of practising ethics in R&I. Participation is seen to be important because there is a plurality of value systems (different ethical perspectives), which means that different values can only be considered when relevant stakeholders participate in the process of practising ethics. Two problems concerning this challenge were identified that cut across the methods.

First, a problem that is inadequately addressed is the appropriate identification of relevant stakeholders: who should be included in the process. Even though many methods formulate procedural steps entailing that stakeholders should be identified, how this should be done remains generally unclear. As Schroeder and Palmer argue when discussing the ethical matrix, “difficulties arise in this analysis both with respect to what constitutes stakeholders”…”and also concerning how to deal with those one might definitely want to include as stakeholders”… “but who are unable to enter deliberative discourse themselves” (Schroeder and Palmer 2003, p. 301). In relation to VSD, Borning and Muller discuss this as “the problem of speaking for others”, of ethicists speaking for those without a voice by, for instance, determining which stakeholders can be considered relevant (Borning and Muller 2012, p. 1130). Additionally, as Ferrari argues, the identification of different stakeholders is based on the problematic assumption that different people with different particular and isolated interests exist (Ferrari 2010, p. 36). Considering the methods that were analysed, these problems do not limit themselves to the ethical matrix and VSD, but extend to all the methods that discuss “stakeholder identification” but do not offer ways how to justifiably do so. The network approach seems to be an exception, by providing an account of relevant stakeholders by offering several criteria for the selection of stakeholders that pertain to the position of a stakeholder in relation to the decision-making process in an R&I project (Zwart et al. 2006, p. 672). This relates to the suggestion of Cotton, who argues that a “meta-ethically justified process for the selection of stakeholders is necessary—a mapping device for identifying actors and the relationships between them” (Cotton 2009, p. 166). Other possible ways to deal with the abovementioned problem is, instead of having a method for stakeholder participation, having a method for collaborative research (Flipse et al. 2013), or by focusing on practising ethics in R&I as a democratic and reflexive discourse (Genus 2006), which would imply that democratic principles should inform the process of participation.

Second, stakeholder participation in general suffers from the problem of a top-down approach, according to which stakeholders are confronted a priori with a framework of principles and concerns. When discussing EIA, Markus and Mentzer criticise the list of values it proposes of being of “only a certain kind”, which means that stakeholders might not be able to engage with values they would deem important (Markus and Mentzer 2014, p. 359). In line with this critique, Borning and Muller question whether VSD should “single out certain values as particularly worthy of consideration” and if so, by whom they should be chosen and how (Borning and Muller 2012, p. 1129). Again, it can be argued that methods that dealing with stakeholder participation face this problem across the board. Ways to deal with this problem are for instance to make value identification dependent on a well-organised participatory process (Bombard et al. 2011) and by taking participatory design “commitments to co-design and power sharing” (Borning and Muller 2012, p. 1131) into account.

As a final note regarding the abovementioned problems, it should be stressed that while participations should be taken into account, its limits when applied to ethical reflection should also be taken into account as for instance Felt et al. (2008) forcefully show. Through the application of procedures to ensure participation, knowledge might certainly be gained about ethical impacts but one might doubt whether this entails some kind of moral judgement. From a philosophical point of view moral judgements are more than fact-finding and moral conclusions seeking to move from “is to ought” are often misguided. Participation can therefore not in and by itself guide the process of practising ethics in R&I.

Recommendations

-

For methods that deal with stakeholder identification, we recommend that they should include considerations of justified stakeholder selection. These considerations could be based on justified criteria or a mapping-framework for stakeholder identification, or could gain from collaborative approaches or approaches guided by democratic principles.

-

For methods that facilitate stakeholder participation in the process of practising ethics in R&I, we recommend that they should include considerations that negate a top-down approach. They could do so by shaping the framework for ethical analysis according to a participatory process or by integrating insights from participatory design in process of practising ethics in R&I.

Concluding Remarks

The previous decades have seen a great increase in discussions about methods for practising ethics in R&I. This literature review provided an overview, an analysis and evaluation of these methods. Consequently, a number of recommendations were formulated that might pave the way toward the development of methods that more adequately answer the ethical challenges posed by contemporary R&I processes. Below, a conceptual map is presented for characterising methods of practising ethics in R&I that offers a comprehensive overview of the analysis in this paper (Fig. 3).

A map for characterising methods for practising ethics in R&I. The centre contains the three main method types: ex ante, intra and ex post. The second circle provides a sub-categorisation of methods according to the type of procedural steps they focus on. The third circle displays the overarching aims of the three main method types and the fourth circle displays the issue common to methods across the main three method types of appropriate stakeholder participation

Notes

In line with Achterkamp and Vos (2008), a stakeholder is conceptualised as either a group or an individual who potentially affects or is affected by an ethical impact and/or has a vested interest in the R&I context to which the ethical impact is ascribed.

Accessed through: http://apps.webofknowledge.com/.

Accessed through: http://www.scopus.com/.

Accessed through: http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/.

This includes “the ethical Matrix”, “ETHICS”, “anticipatory ethics”, “ethical technology assessment”, “ethical impact assessment”, “ethical dilemma scenarios”, “value sensitive design”, “the SBU approach”, “the walkshop approach”, “ethical parallel research”, “just war theory”, “human practices approach” and “interactive technology assessment”.

Three sources were left out of the final selection because they were not available (they used two different institutional subscription systems).

Van den Hoven (2008) also typifies methods in computer ethics as “ex ante” (emphasis on design) and “ex post” (emphasis on evaluation of existing technologies). However, we introduce the “intra” type to distinguish between methods that focus on the design process in which the conceptual steps have already been taken (a general idea of the type of technology is already present) vis-à-vis “ex ante” methods that focus on technological systems, artefacts and applications that might be designed at some point but have not entered the design process yet.

By targeted user is meant the type of person who would use the method when engaging with ethics in R&I. The user could also be termed an “assessor”, i.e., the person who is responsible for conducting an ethics assessment or review.

It should be noted that Rehg’s version of discourse ethics could also be characterised as ex post, which would explain the greater focus on a variety of stakeholders.

References

Achterkamp, M. C., & Vos, J. F. J. (2008). Investigating the use of the stakeholder notion in project management literature, a meta-analysis. International Journal of Project Management, 26(7), 749–757. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.10.001.

Addissie, A., Davey, G., Newport, M. J., Addissie, T., MacGregor, H., Feleke, Y., et al. (2014). A mixed-methods study on perceptions towards use of rapid ethical assessment to improve informed consent processes for health research in a low-income setting. BMC Medical Ethics, 15(1), 35. doi:10.1186/1472-6939-15-35.

Adman, P., & Warren, L. (2000). Participatory sociotechnical design of organizations and information systems—An adaptation of ETHICS methodology. Journal of Information Technology, 15(1), 39–51. doi:10.1080/026839600344393.

Albrechtslund, A. (2007). Ethics and technology design. Ethics and Information Technology, 9(1), 63–72. doi:10.1007/s10676-006-9129-8.

Apel, K.-O. (1980). Towards a transformation of philosophy. (G. Adey and D. Frisby, Trans.). Routledge and Kegan Paul: London.

Arellano, L. E., Willett, J. M., & Borry, P. (2011). International survey on attitudes toward ethics in health technology assessment: An exploratory study. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 27(1), 50–54. doi:10.1017/S0266462310001182.

Ashcroft, R. (1999). Ethics and health technology assessment. Monash Bioethics Review, 18(2), 15–24.

Autti-Ramo, I., & Makela, M. (2007). Ethical evaluation in health technology assessment reports: An eclectic approach. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 23(1), 1–8. doi:10.1017/S0266462307051501.

Bailey, M., Dittrich, D., & Kenneally, E. (2013). Applying ethical principles to information and communication technology research: A companion to the menlo report, (October), 14. Retrieved from http://www.caida.org/publications/papers/2013/menlo_report_companion_actual_formatted/menlo_report_companion_actual_formatted.pdf.

Balmer, A. S., & Bulpin, K. J. (2013). Left to their own devices: Post-ELSI, ethical equipment and the international genetically engineered machine (iGEM) competition. BioSocieties, 8(3), 311–335. doi:10.1057/biosoc.2013.13.

Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2001). Principles of biomedical ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beekman, V., & Brom, F. W. A. (2007). Ethical tools to support systematic public deliberations about the ethical aspects of agricultural biotechnologies. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 20(1), 3–12. doi:10.1007/s10806-006-9024-7.

Bitay, B., Brandtand, D., & Savelsberg, E. (2005). The global validity of ethics: Applying ethics to engineering and technology development. IFAC Proceedings Volumes (IFAC-PapersOnline), 16, 19–24.

Boenink, M., Swierstra, T., & Stemerding, D. (2010). Anticipating the interaction between technology and morality: A scenario study of experimenting with humans in bionanotechnology. Studies in Ethics, Law, and Technology, 4, 1. doi:10.2202/1941-6008.1098.

Bohn, J., Coroama, V., Langheinrich, M., & Mattern, M. (2005). Social, economic, and ethical implications of ambient intelligence and ubiquitous computing. Ambient Intelligence, 10(5), 5–29. doi:10.1007/3-540-27139-2_2.

Bombard, Y., Abelson, J., Simeonov, D., & Gauvin, F.-P. (2011). Eliciting ethical and social values in health technology assessment: A participatory approach. Social Science and Medicine, 73(1), 135–144. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.017.

Borning, A., & Muller, M. (2012). Next steps for value sensitive design. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual conference on human factors in computing systems—CHI’12, (pp. 1–10).

Borup, M., Brown, N., Konrad, K., & Van Lente, H. (2006). The sociology of expectations in science and technology. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 18(3–4), 285–298. doi:10.1080/09537320600777002.

Bose, U. (2012). An ethical framework in information systems decision making using normative theories of business ethics. Ethics and Information Technology, 14(1), 17–26. doi:10.1007/s10676-011-9283-5.

Boucher, P., & Gough, C. (2012). Mapping the ethical landscape of carbon capture and storage. Poiesis Und Praxis, 9(3–4), 249–270. doi:10.1007/s10202-012-0117-2.

Brans, J. P. (2004). The management of the future Ethics in OR: Respect, multicriteria management, happiness. European Journal of Operational Research, 153(2), 466–467. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(03)00166-8.

Braunack-Mayer, A. J. (2006). Ethics and health technology assessment: Handmaiden and/or critic? International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 22(3), 307–312. doi:10.1017/S0266462306051191.

Brey, P. (2000). Disclosive computer ethics: The exposure and evaluation of embedded normativity in computer technology. Computers and Society, 30(4), 10–16.

Brey, P. (2012a). Anticipating ethical issues in emerging IT. Ethics and Information Technology, 14, 305–317. doi:10.1007/s10676-012-9293-y.

Brey, P. (2012b). Anticipatory ethics for emerging technologies. NanoEthics, 6(1), 1–13. doi:10.1007/s11569-012-0141-7.

Bruijnis, M. R. N., Blok, V., Stassen, E. N., & Gremmen, H. G. J. (2015). Moral lock-in in responsible innovation: The ethical and social aspects of killing day-old chicks and its alternatives. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 28(5), 939–960. doi:10.1007/s10806-015-9566-7.

Burget, M., Bardone, E., & Pedaste, M. (2017). Definitions and conceptual dimensions of responsible research and innovation: A literature review. Science and Engineering Ethics, 23(1), 1–19. doi:10.1007/s11948-016-9782-1.

Burls, A., Caron, L., Cleret de Langavant, G., Dondorp, W., Harstall, C., Pathak-Sen, E., et al. (2011). Tackling ethical issues in health technology assessment: A proposed framework. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 27(3), 230–237. doi:10.1017/S0266462311000250.

Carew, P. J., & Stapleton, L. (2013). Towards empathy: A human-centred analysis of rationality, ethics and praxis in systems development. AI & Society, 29(2), 149–166. doi:10.1007/s00146-013-0472-0.

Carpenter, K. J., & Dittrich, D. (2013). Bridging the distance: Removing the technology buffer and seeking consistent ethical analysis in computer security research. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 53(9), 1689–1699. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Cotton, M. (2009). Evaluating the “ethical matrix” as a radioactive waste management deliberative decision-support tool. Environmental Values, 18(2), 153–176. doi:10.3197/096327109X438044.

Decker, M. (2004). The role of ethics in interdisciplinary technology assessment. Poiesis & Praxis: International Journal of Technology Assessment and Ethics of Science, 2(2–3), 139–156. doi:10.1007/s10202-003-0047-0.

DeJean, D., Giacomini, M., Schwartz, L., & Miller, F. A. (2009). Ethics in Canadian health technology assessment: A descriptive review. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 25(4), 463–469. doi:10.1017/S0266462309990390.

Doorn, N. (2012). Responsibility ascriptions in technology development and engineering: Three perspectives. Science and Engineering Ethics, 18(1), 69–90. doi:10.1007/s11948-009-9189-3.

Drake, M. J., Gerde, V. W., & Wasieleski, D. M. (2009). Socially responsible modeling: A stakeholder approach to the implementation of ethical modeling in operations research. OR Spectrum, 33(1), 1–26. doi:10.1007/s00291-009-0172-9.

Droste, S., Dintsios, C. M., & Gerber, A. (2010). Information on ethical issues in health technology assessment: How and where to find them. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 26(4), 441–449. doi:10.1017/S0266462310000954.

Duthie, K., & Bond, K. (2011). Improving ethics analysis in health technology assessment. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 27(1), 64–70. doi:10.1017/S0266462310001303.

Fassin, Y. (2000). Innovation and ethics ethical considerations in the innovation business. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(1/2), 193–203. doi:10.1023/A:1006427106307.

Felt, U., Fochler, M., Muller, A., & Strassnig, M. (2008). Unruly ethics: On the difficulties of a bottom-up approach to ethics in the field of genomics. Public Understanding of Science, 18(3), 354–371. doi:10.1177/0963662507079902.

Ferrari, A. (2010). Developments in the debate on nanoethics: Traditional approaches and the need for new kinds of analysis. NanoEthics, 4(1), 27–52. doi:10.1007/s11569-009-0081-z.

Flipse, S. M., van der Sanden, M. C. A., & Osseweijer, P. (2013). The why and how of enabling the integration of social and ethical aspects in research and development. Science and Engineering Ethics, 19(3), 703–725. doi:10.1007/s11948-012-9423-2.

Floridi, L. (2015). Tolerant paternalism: Pro-ethical design as a resolution of the dilemma of toleration. Science and Engineering Ethics. doi:10.1007/s11948-015-9733-2.

Foley, R. W., Bennett, I., & Wetmore, J. M. (2012). Practitioners’ views on responsibility: Applying nanoethics. NanoEthics, 6, 231–241. doi:10.1007/s11569-012-0154-2.

Forsberg, E. (2004). The ethical matrix—A tool for ethical assessments of biotechnology Ellen–Marie Forsberg. Global Bioethics. doi:10.1080/11287462.2004.10800856.

Forsberg, E. M. (2007). Pluralism, the ethical matrix, and coming to conclusions. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 20, 455–468. doi:10.1007/s10806-007-9050-0.

Forsberg, E. M., Thorstensen, E., Nielsen, R. Ø., & de Bakker, E. (2014). Assessments of emerging science and technologies: Mapping the landscape. Science and Public Policy, 41(3), 306–316. doi:10.1093/scipol/scu025.

Friedman, B. (1996). Value-sensitive design. Interactions, 3(6), 16–23. doi:10.1145/242485.242493.

Friedman, B., Kahn, P. H., & Borning, A. (2006). Value sensitive design and information systems. In K. E. Himma & H. T. Tavani (Eds.), Human–computer interaction and management information systems: Foundations (pp. 1–27). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. doi:10.1145/242485.242493.

Gamborg, C. (2002). The acceptability of forest management practices: An analysis of ethical accounting and the ethical matrix. Forest Policy and Economics, 4(3), 175–186. doi:10.1016/S1389-9341(02)00007-2.

Genus, A. (2006). Rethinking constructive technology assessment as democratic, reflective, discourse. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 73(1), 13–26. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2005.06.009.

Geoghegan-Quinn, M. (2014). Responsible research & innovation. Brussels: European Union Publications Office.

Graffigna, G., Bosio, A. C., & Olson, K. (2010). How do ethics assessments frame results of comparative qualitative research? A theory of technique approach. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 13(4), 341–355. doi:10.1080/13645570903209076.

Groves, C. (2013). Horizons of Care: From Future Imaginaries to Responsible Research and Innovation. In K. Konrad, C. Coenen, A. Dijkstra, C. Milburn, & H. Van Lente (Eds.), Shaping emerging technologies: Governance, innovation, discourse (pp. 185–202). Berlin: IOS Press.

Groves, C. (2015). Logic of choice or logic of care? Uncertainty. Technological Mediation and Responsible Innovation. NanoEthics, 9(3), 321–333. doi:10.1007/s11569-015-0238-x.

Grunwald, A. (2000). Against over-estimating the role of ethics in technology. Science and Engineering Ethics, 6(2), 181–196. doi:10.1007/s11948-000-0046-7.

Grunwald, A. (2001). The application of ethics to engineering and the engineer’s moral responsibility: Perspectives for a research agenda. Science and Engineering Ethics, 7(3), 415–428. doi:10.1007/s11948-001-0063-1.

Grunwald, A. (2004). The normative basis of (health) technology assessment and the role of ethical expertise. Poiesis & Praxis: International Journal of Technology Assessment and Ethics of Science, 2, 175–193. doi:10.1007/s10202-003-0050-5.

Grunwald, A. (2011). Responsible innovation: Bringing together technology assessment, applied ethics, and STS research. Enterprise and Work Innovation Studies IET, 7, 9–31.

Habermas, J. (1990). Moral consciousness and communicative action. (C. Lenhardt and S. W. Nicholsen Trans.). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hauser, J., Tellis, G. J., & Griffin, A. (2006). Research on innovation: A review and agenda for marketing science. Marketing Science, 25(6), 687–717. doi:10.1287/mksc.1050.0144.

Heintz, E., Lintamo, L., Hultcrantz, M., Jacobson, S., Levi, R., Munthe, C., et al. (2015). Framework for systematic identification of ethical aspects of healthcare technologies: The Sbu approach. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 31(3), 124–130. doi:10.1017/S0266462315000264.

Heleski, C. R., & Anthony, R. (2012). Science alone is not always enough: The importance of ethical assessment for a more comprehensive view of equine welfare. Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research, 7(3), 169–178. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2011.08.003.

Herkert, J. R. (2001). Future directions in engineering ethics research: Microethics, macroethics and the role of professional societies. Science and Engineering Ethics, 7(3), 403–414. doi:10.1007/s11948-001-0062-2.

Hirschheim, R., & Klein, H. K. (1994). Realizing emancipatory principles in information systems development: The case for ETHICS. MIS Quarterly, 18(1), 83–109. doi:10.2307/249611.

Hofmann, B. (2005a). On value-judgements and ethics in health technology assessment. Poiesis Und Praxis, 3(4), 277–295. doi:10.1007/s10202-005-0073-1.

Hofmann, B. (2005b). Toward a procedure for integrating moral issues in health technology assessment. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 21(3), 312–318. doi:10.1017/S0266462305050415.

Hofmann, B. M. (2008). Why ethics should be part of health technology assessment. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 24(4), 423–429. doi:10.1017/S0266462308080550.

Hofmann, B. (2014). Why not integrate ethics in HTA: Identification and assessment of the reasons. GMS Health Technology Assessment, 10, 1–9. doi:10.3205/hta000120.