Abstract

Policy makers call upon researchers from the natural and social sciences to collaborate for the responsible development and deployment of innovations. Collaborations are projected to enhance both the technical quality of innovations, and the extent to which relevant social and ethical considerations are integrated into their development. This could make these innovations more socially robust and responsible, particularly in new and emerging scientific and technological fields, such as synthetic biology and nanotechnology. Some researchers from both fields have embarked on collaborative research activities, using various Technology Assessment approaches and Socio-Technical Integration Research activities such as Midstream Modulation. Still, practical experience of collaborations in industry is limited, while much may be expected from industry in terms of socially responsible innovation development. Experience in and guidelines on how to set up and manage such collaborations are not easily available. Having carried out various collaborative research activities in industry ourselves, we aim to share in this paper our experiences in setting up and working in such collaborations. We highlight the possibilities and boundaries in setting up and managing collaborations, and discuss how we have experienced the emergence of ‘collaborative spaces.’ Hopefully our findings can facilitate and encourage others to set up collaborative research endeavours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Context

New and Emerging Science and Technology (NEST), including life science and nanotechnology, raise social and political concerns pertaining to their potential impact on society (Barling et al. 1999; Berne 2004; Fisher and Mahajan 2006; Swierstra and Jelsma 2006). Policymakers in Europe and elsewhere therefore call for ‘responsible innovation’ practices to encourage innovators to address such concerns, e.g. by integrating considerations on social and ethical aspects in research and development (R&D) practices (21st century Nanotechnology Act 2003; European Group on Ethics 2007; European Commission 2011a; Von Schomberg 2011; PBL 2012). Scholars from the social sciences and humanities have answered that call by embarking on interdisciplinary research activities, such as Technology Assessment, Midstream Modulation and Ethical Parallel Research, which aim to make timely reflection on social and ethical aspects an integrated part of innovation practice (Schot and Rip 1997; Fisher and Mahajan 2006; Van der Burg 2009; Schuurbiers 2011). Even though practical experience in such activities remains limited, the growing body of literature sparks some enthusiasm: the explicit consideration of social and ethical aspects by NEST researchersFootnote 1 can enhance their own thinking and decision-making processes (Fisher and Mahajan 2006) and help them set better research goals and priorities (Van der Burg 2009). Also, such considerations may make R&D decision processes more democratic, thereby allowing public viewpoints to be included in innovation processes (Van de Poel 2000; Nowotny 2003; Genus and Coles 2005), prevent public backlash (Editorial 2009) and make innovations more socially robust (Nowotny et al. 2003).

Still, these interdisciplinary R&D collaborations, between NEST researchers and social scientists, have mostly been carried out in academic research environments, while the corporate R&D environment remains largely unstudied, also in terms of collaborative research endeavours (Shapin 2008; Penders et al. 2009a). Nevertheless, most R&D in terms of money and labour intensity occurs in industry (European Commission 2011b). Also, especially in industry collaborative approaches aiming for improved and more socially responsible innovation practices can be considered important, since industrial innovations arguably have a more prominent and immediate effect in society than academic R&D outcomes. But industry may be hesitant to allow outsiders to visit, study or work in their R&D facilities, for reasons of intellectual property and confidentiality (Wilsdon and Willis 2004; Bercovitz and Feldman 2007). Companies are cautious about their brands and public image (Aaker and Jacobson 2001; Van Riel and Fombrun 2007), particularly in areas characterised by low public appreciation, such as biotechnology (Gaskell et al. 2011; Henderson et al. 2007), and the chemical industry (Burningham et al. 2007). As such, collaborative activities are reported to be difficult to set up (Doubleday 2004; Wilsdon and Willis 2004; Penders et al. 2009a; Radstake et al. 2009; Patra 2011).

Aim and Structure

Toolkits that are helpful in setting up research studies for integration of considerations of social and ethical aspects in industrial R&D environments are not easily available. Authors of papers reporting on the outcome of collaborative activities hardly explain how such initiatives were negotiated and initiated. Some confirmed that access to (industrial) researchers is difficult to acquire. In this paper we add to the growing body of empirical literature on collaborative research in R&D practice, and aim to zoom in on the practical implications of setting up and conducting collaborative research in the corporate R&D environment. We do so based on our own experiences in various research studies with NEST researchers in industry (Osseweijer et al. 2010; Flipse and Osseweijer 2013; Flipse and Penders 2012; Flipse et al. 2012) in the field of the Life Sciences.Footnote 2

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. “Mapping and Navigating the Field: Setting Up Collaborations” elaborates on setting up collaborations between researchers from the natural and social sciences. “Fieldwork: Creating Spaces for Collaboration” covers our experiences in managing such collaborations. In “Building Collaborative Spaces” we expand on the notion of the ‘collaborative space,’ as an enabling heuristic for successfully setting up collaborative R&D for more socially responsible R&D projects. Last, in “Concluding Remarks and Recommendations” we summarise our findings and present an integrative figure based on our experiences. We also propose various recommendations for researchers aspiring to set up and work in collaborative spaces.

Mapping and Navigating the Field: Setting Up Collaborations

Initiatives for setting up collaborative engagements between researchers from the social and natural sciences have mostly come from researchers from the social sciences/humanities who wished to interact with researchers from the natural sciences. This was also the case in our own collaborative endeavours, which served a twofold purpose. First, we wished to study the corporate R&D environment, to assess to what extent such environments are amendable to considerations of social and ethical aspects. Secondly, we wished to ascertain to what extent such considerations would lead to an improvement of R&D practices. Using Midstream Modulation (Fisher et al. 2006; Fisher and Mahajan 2006) as the main collaborative socio-technical integration protocol we proposed to set up such research in the form of a research study with industrial NEST researchers (Flipse et al. 2012). We first elaborate on two unsuccessful attempts in acquiring a research partner for collaborative research at two companies and address what we learned from those experiences. Then we cover how we successfully negotiated other research studies.Footnote 3

Success Versus Failure in Innovation Projects

In one of our invitations for a collaborative research study we addressed a Life Sciences based company,Footnote 4 and suggested that our research could improve the quality of product R&D and could help the company understand why some products are more successful than others. For a comprehensive product portfolio review we wished to investigate both successful and failed innovations. We wrote a project proposal to one of the company’s R&D managers. After some time, this particular company replied that it had no ‘failed’ products, and that our proposed research would therefore best not be carried out at that company.

While this absence of ‘failed’ products might be true from a market perspective, we could not imagine that all the company’s R&D projects would in fact be successful. We soon recognised a contextual difference between ‘success’ in market performance and ‘success’ in R&D quality. While we wanted to investigate R&D quality, the R&D project manager possibly perceived we wanted to investigate market success, which might be considered ‘too sensitive’ to discuss. To avoid such possible misunderstandings, in our later communication with other companies we refrained from speaking explicitly about ‘failed’ projects, and made explicit that our interests were primarily in product development and not in marketing and communication.

Similarly, in reporting on one of the research studies that we did successfully initiate and later coordinate, we wished to make explicit the difference between successful and unsuccessful R&D projects. In our reports, we were urged not describe these projects as ‘unsuccessful.’ The company proposed to call these projects ‘less successful’ instead, for still much could be learned from these projects.

These examples show that terminology regarding project success is considered a highly sensitive subject by companies. Interestingly, once we were engaged for several weeks in one collaborative research study within a different company, we talked to researchers and other personnel about what distinguished successful from less successful projects during an informal lunch break. One of the people at the table, a former researcher, was asked to what extent the company kept track of ‘failed innovation projects.’ The ex-researcher joked: “yes, of course, it’s called the R&D archive,” indicating that most projects are not so very successful in the sense that they are not developed into marketable products. While such things were not so easily admitted before our studies began, researchers themselves appeared quite open about, and interested in, what distinguishes success from failure once we were granted access.

Addressing the Appropriate Persons Appropriately

Identifying and approaching the right people helps in proposing any sort of collaborative activity that requires participation from the other party. In proposing a research study at a certain company, we figured that the right person to address was a corporate R&D manager, who we also knew professionally through our professional networks. We sent an email with a carefully formulated collaborative research proposal, yet after several weeks we had not received any reply. After 1 month we sent out a polite reminder, without any response. When we attended a conference several weeks later, another person from this company, who knew this R&D manager, approached us personally and stated that we were kindly requested to stop ‘bothering’ him with our ideas. Apparently the manager got annoyed with our (nevertheless kindly formulated) requests. While one may only speculate on the reasons for this reaction (e.g. pertaining to ourselves, in trust in our competence, or to the industrial representative for perhaps being too high in the company hierarchy or too far from actual R&D where our approaches were supposed to be exploited, or any other reason), the fact of the matter is we had to try to gain access somewhere else and in another way. Proposing our ideas too high up in the hierarchy of a large R&D organisation, far from where the activity is supposed to have an effect, turned out to be counterproductive in this particular case.

Personal Development and Confidentiality

For the research studies we eventually established, short proposals were sent to R&D project managers via an enthusiastic contact person working at the company, who we had met personally and who was convinced of the usefulness of our research ideas. We were of course careful to avoid speculations on the investigation of ‘failed’ or ‘unsuccessful’ projects. Inspired by the work of Fisher (Fisher and Mahajan 2006; Fisher et al. 2006), we proposed that our study might encourage and help researchers in out-of-the-box thinking for facilitating the generation of creative ideas and for creating reflective awareness on the social and ethical dimensions of their work. We argued that involvement of the researchers could enhance their responsive capacity on new and emerging science and technology, while simultaneously enabling self-transformative inquiry. This can potentially encourage them to integrate social and ethical considerations into their activities, leading to more socially robust innovations.

In discussing our project proposals after being invited at this company to illustrate our ideas in person, we learned that companies wanted to participate for various reasons. Our industrial contacts were positive about the possibilities for personal development, which they stated sparked their enthusiasm for participating in our research study. Nevertheless, they would only do so if a confidentiality agreement was drafted that safeguarded the scientific and technical details of their work and the identity of the participants.

Fieldwork: Creating Spaces for Collaboration

Altogether, with continuous fine-tuning of our invitations to various potential research partners and drafting an official confidentiality agreement,Footnote 5 it took us roughly 1 year to obtain our first research study agreement from the moment of the first invitation. Still, acquiring access is one thing—actually doing social scientific fieldwork is something else. Conducting qualitative research, specifically in R&D environments in companies, is not really common practice; while several books (Feldman et al. 2003; Bryman 2012; and more specifically for industry research, Cassell and Symon 2004) provide valuable guidelines for organising research activities, these focus primarily on sample selection and data collection and analysis. For relatively new collaborative research activities focusing explicitly on the integration of considerations of social and ethical aspects, no standard guidelines exist. In this section we present some of our considerations in setting up collaborations with researchers from industry. We present first a situation that we have encountered that we had hoped to avoid, followed by various factors that have aided in successfully setting up collaborations in industrial R&D practice.

Role Clarity: Avoiding the ‘Watchdog’

Generally, NEST researchers are unaware of the broader social and ethical contexts of their work (Patra 2011), have difficulties identifying societal impact (Owen and Goldberg 2010) and are sometimes even encouraged to explicitly ignore such contexts (Fisher and Miller 2009). As such, it seems unlikely that they will start to consider such aspects by themselves. In collaborative approaches (such as Midstream Modulation, see Fisher et al. 2006), initiatives and incentives for them to adopt more reflective practices have come mainly from the social scientists or humanities scholars who wished to study R&D environments. Yet, these social scientists may experience difficulties in being taken seriously by researchers from the natural sciences.

Past approaches in which researchers from both fields worked together, such as Technology Assessment approaches (Schot and Rip 1997), have often focused on potential risks and have assessed technology-in-the-making for its potential societal impact (Delgado et al. 2010). As such, these activities focused primarily on potential wrong-doing by researchers, using a backward-looking responsibility perspective (Doorn and Fahlquist 2010). Through such activities, participating researchers from the natural sciences may have developed a ‘watchdog’ characterisation of researchers from the social sciences and humanities, who indicated what research should not be done. Even though recent activities adopt a forward-looking responsibility perspective, focusing on how to deploy responsible innovation practices, such watchdog perceptions may linger in the minds of researchers from the natural sciences, making them hesitant to collaborate with social scientists.

To give an example, during one research study, the participant and engaging social scientist were discussing the progress of the collaborative activity. Participants were asked on multiple occasions to be critical of their interaction with the social scientist. In reflecting on the activity, one of our research participants at one of our participating companies indicated that at the beginning of the activity, he felt he was being judged for what he did and did not do:

- Participant::

-

It feels to me, sometimes, more like an evaluation than an observation.

- Social scientist::

-

It does? I don’t mean to do that.

- P::

-

Maybe it’s just part of this setting. I try to do things right, but sometimes it feels like being assessed. But maybe it’s something I’m susceptible to.

- S::

-

I don’t know. It’s not the case that there is only one right answer to some of my questions.

- P::

-

Yes, that’s probably true. [Interview, 2 May 2011].

The participant commented that he felt as if he was under evaluation, whilst the collaborating social scientist never intended for him to feel that way. After some time he said that that feeling disappeared, but it did make the engager very aware of the role (s)he plays when carrying out such a research study in industry. The social scientist will want to avoid watchdog allegations, yet a critical view of on-going R&D work may not always prevent coming across as one. Even though, this was the only participant who made a critical comment in all our studies, we wished to illustrate how the engaging social scientist can painfully be made aware of how (s)he can be seen.

A Willing ‘Sample’

Literature on qualitative research advises to take special care in selecting a representative ‘sample.’ In collaborative approaches it is researchers in natural sciences fields who participate in the described collaborative research studies. However, possibly even more so in industry than in academia, social scientists are not always free to select their participant sample. Frequently, participants are assigned to the study and the social scientist can only steer the selection to a limited extent.Footnote 6 Good agreements have to be made with R&D management,Footnote 7 therefore, on the goals, methods and means of the study. Our participants were selected partly based on our criteria (depending on the research we wanted to conduct), partly based on criteria of the company (depending on who, and which projects, R&D management thought were most appropriate), and partly based on practical aspects (depending, e.g. on who was on holiday or otherwise unavailable). Access was limited and of course we had to abide by the confidentiality agreement, which restricted access to other resources and persons than those directly relevant to or participating in the study. While our samples could be considered adequate, a better or more rich sample might have been imaginable.

Probably, forceful participation is not fruitful for the quality and success of collaborative approaches. Still, researchers were willing to participate, and stated that they were open to our presence at the beginning of our studies. ‘Collaboration’ implies a degree of voluntariness on the parts of the participating parties. We experienced that once the relationship advances, critical viewpoints are more readily tolerated, leading to more interesting discussions on the value of reflecting on social and ethical aspects during innovation practices. In time, the natural scientists start to understand these considerations better, whilst simultaneously the social scientist increasingly understands R&D considerations. Ultimately this leads to a situation in which both parties gain credibility, start to understand one another’s arguments, and use one another’s suggestions. In our studies, such situations emerged after 4–8 weeks of weekly interaction. Ultimately, all participants highlighted the particular usefulness to them of the activities we embarked on, mostly pertaining to public health, environmental sustainability, corporate social responsibility, communication and cooperation. They state the interaction with the social scientist made them consider things they had not considered otherwise, which they felt increased the quality of their work (Flipse et al. 2012).

Relationship Development

In our experience, researchers will only adopt considerations of social and ethical aspects if they see the relevance for, and use in, doing so. Before the relevance and use of social and ethical aspects can be elucidated, the natural scientist will have to learn about these social and ethical considerations, while the social scientist has to learn about R&D practice. In our experience, both must develop a certain mutual credibility to make suggestions that may be taken seriously. Historically, researchers from the natural and social sciences have spoken different ‘languages’ and as such had difficulties in understanding one another (Snow 1959). The two ‘cultures’ use different terminology and research approaches which can be hard to align. The integration of ‘soft’ (Van der Burg 2010) social and ethical considerations in ‘hard’ evidence-based R&D work may also prove challenging because of these potential differences in language.

The mere identification of such aspects does not make practices more socially responsible, which was a goal of our research study activities. Aspects can be identified, only to be quickly discarded without being used in practice (Johnson 2007). The challenge is to establish a link between social and ethical aspects, and innovation practice. In collaborative approaches this is done by combining expertise from both natural and social scientific fields (cf. Schuurbiers 2011). The task in collaborative approaches is to integrate natural and social scientific perspectives, which requires the exchange of knowledge and experiences. A form of trust must develop between the two types of researchers, and a reasonably good relationship should develop in which such knowledge and experience can be usefully exchanged. Ultimately this takes time. In our cases we experienced (as indicated above) 4–8 weekly interactions were enough. This indicates that only through sustained interaction can an environment emerge in which critical reflection on both social and ethical aspects and the innovation practice plays a role.

What probably also benefitted successful interaction between the social and natural scientist in our research studies was that the engaging social scientist had a certain degree of initial knowledge of the scientific and technological fields in which the natural scientists were working. As indicated earlier, speaking one another’s language is of major importance in collaborations between fields that originally speak different languages. In our experience, our natural scientific colleagues appreciated that they did not have to explain every technological principle of their work, which facilitated discussions on the social and ethical aspects related to those technological principles.

Building Collaborative Spaces

Participating in collaborative research activities made us aware of the concept of ‘collaborative spaces,’ as an enabling heuristic for successful, more socially responsible R&D projects. Below we first relate the concept of collaborative spaces to other similar concepts. Second, we describe various elements necessary for such spaces to emerge.

Introducing ‘Collaborative Spaces’

Collaboration can be described as working together to reach certain goals. In our experience, such goals need not necessarily be mutual. In our collaborative endeavours the goals of the participating parties always were clear. The natural scientists wished to enrich and improve their decision-making processes through the consideration of social and ethical aspects, thereby possibly making their practices more socially responsible. The social scientist wished to investigate a social scientific concept or method (e.g. knowledge production in private laboratories, or the functionality of Midstream Modulation as a method to stimulate responsible innovation practices, see e.g. Fisher and Mahajan 2006; Penders et al. 2009a), also possibly resulting in making R&D practices more socially responsible.

This kind of collaboration shows similarities to the concept of ‘trading zones’ as proposed by Gorman (2002), based on Galison (1997) and Collins and Evans (2002). Collins, Evans and Gorman together state that the term ‘trading zone’ is “often used to denote any kind of interdisciplinary partnership in which two or more perspectives are combined and a new, shared language develops” (Collins et al. 2007: 657). This can also be the case for the collaborations described in this paper. Similar to trading zones, some trading of expertise and knowledge occurs in collaborative spaces. Possibly, collaborative spaces can even be considered a specific kind of trading zone.

However, there are four aspects in which collaborative spaces and trading zones appear to differ. First, in collaborative spaces, trading is not an end, rather a means to the end of more responsible innovation practices. The kind of collaboration we engaged in was not ‘tit-for-tat’: instead we looked for a situation in which the two parties recognised and valued one another’s contributions to the project, and on that basis collaborated (Calvert and Martin 2009; Fisher et al. 2010). A stage of ‘mutual benefit’ needs to be reached, otherwise one of the partners may end up frustrated from ‘working together’ (Penders et al. 2009b). Second, the collaborative spaces we describe are located exclusively at laboratory sites where R&D is actually happening, while trading zones are described more generally and can seemingly take place anywhere. Third, trading zones can be established voluntarily but can also be coerced, while we have experienced our collaborations only to work when both parties are willing to participate.Footnote 8 Fourth, our collaborations rely on a specific kind of interdisciplinary partnership, namely exclusively between researchers from the natural and from the social sciences.

As such, the interdisciplinary partnerships within collaborative spaces can be considered places of ‘boundary work,’ as defined by Gieryn (1983: 782, but also see Stegmaier 2009) as the “attribution of selected characteristics to the institution of science (i.e. to its practitioners, methods, stock of knowledge, values and work organization) for purposes of constructing a social boundary that distinguishes some intellectual activities as ‘non-science’ [i.e. outside that boundary].” The social scientist initiating the collaboration can be considered the ‘boundary worker’ who tries to identify these boundaries and find ways to cross them (Leigh Star and Griesemer 1989), in particular in relation to the social and ethical aspects of R&D work.

Collaborative spaces also show similarities to ‘communities of practice’ (Wenger 1998), in the sense that communities of practice consist of people who may share a concern or a passion for something they do, and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly. Yet, in collaborative spaces, these concerns or passions are not known beforehand, but only emerge as interaction progresses. Also, while these communities consist of people from similar disciplines who can contribute equally to the community, the collaborative spaces we were engaged in consisted of people from different disciplines,Footnote 9 where different yet complementary knowledge leads to a higher-level, better outcome rather than simply generating more information on a particular topic.

Reciprocal Learning and Role Changes

Through our experiences participating in collaborative research activities, we observed such activities to be a learning experience for all parties involved. Ultimately, both the natural and social scientist change through their interaction. When interaction begins, the social scientist will not know the technical details of the R&D work. (S)he will have to observe and learn about R&D practices first; commenting on R&D practice without thorough knowledge on such practice would not only be meaningless, but also inappropriate. A relationship needs to be established between the natural and social scientist before critical views can be articulated (Schuurbiers 2011). As our practical examples above show, early in one of our collaborative activities, one researcher felt assessed, rather than working together with the social scientist. A collaborative space was yet to emerge, as the collaboration progressed. We noticed that as our own knowledge of the technical details increased, so grew our ability to comment critically on these details. Our feedback was no longer perceived to be inappropriate, and we asked the right questions to enable a critical reflection on on-going R&D practices. In our experience, the role of the social scientist evolved from observer to contributor to collaborator (cf. Calvert and Martin 2009).

Similarly, the participating NEST researchers changed during our collaborative activities. At the beginning of our activities, we asked participants whether they considered participation something extra, adding to their original workload. Even though they were all willing to participate, they mostly replied that they considered it something on top of their work. We noticed that the participants were eager to start, yet also sceptical of what they might gain from partaking. Yet, as the collaborative activities progressed, they became more enthusiastic about the meetings, shared interesting experiences, asked relevant questions and began first to see the relevance of social and ethical aspects, and later the use of integrating these in their R&D practice. Moreover, once the collaborative research project had ended, all stated that they considered reflection on such aspects as part of their job, rather than as something extra, on top of their work (Flipse et al. 2012).

Still, a challenge for the social scientist working in collaborative spaces remains not to highlight social and ethical aspects explicitly. While social scientists do not want to be perceived as watchdogs, stating what research not to do, neither do they likely want to be seen as tracker dogs, indicating potentially relevant social and ethical aspects. Part of the task of social scientists in early technology assessment initiatives was to identify social and ethical aspects and to point out possible places or moments where considerations of social and ethical aspects could be included (Smits et al. 1995). Ultimately this may lead to a perceived division of (moral) labour (Rip 2010), where natural scientists do their science and social scientists add social and ethical considerations. In collaborative approaches, however, such efforts are not to be divided; rather the responsibility for the consideration of social and ethical aspects is shared between them (Doorn and Fahlquist 2010; Fisher et al. 2006). The challenge, then, is for the social scientist to set up a more Socratic learning environment (Calleja-Lopez and Fisher 2009), allowing the NEST researcher to see and understand—for themselves—the relevance and use of integrating considerations of social and ethical aspects.

Going ‘Partially’ Native

Researchers in all studies—natural or social scientific—should worry about the integrity of their research. Still, setting up social scientific studies in ‘impure’ commercial organisations can be perceived particularly challenging for those aiming to do so (Penders et al. 2009a). In our cases, industry expected something in return for participation, possibly pressuring social scientists to make and keep promises, e.g. pertaining to the personal development of the participating natural scientists. Collaborative approaches rely on social scientists to embed themselves in natural scientists’ R&D facilities, with a danger of becoming too much submerged, losing the ability to critically reflect on R&D practice, and addressing themselves more to the fulfilment of their promises than to their original research goals (Wynne 2007). Yet it is also questionable to what extent mere ‘outside’ criticism will lead to changes in R&D toward more socially responsible practices. There may be possibilities in between, where social scientists go ‘partially’ native (Rip, in Schuurbiers 2010: 91). Establishing a relationship with participating researchers requires proximity to their activities. Only through interacting on R&D context-specific topics does the social scientist gain credibility. Natural scientists accept the social scientists’ questions and remarks as legitimate only after some time, once both have become more acquainted with one another’s viewpoints and considerations.

In going ‘partially’ native there are probably things that ‘partially embedded’ social scientists should or should not do. Still, in our studies, a good relationship is not only established during formal interaction hours, but also during coffee breaks, lunches and Friday afternoon drinks. If anything, a good relationship ensures even more critical viewpoints to be taken seriously, allowing for a more serious deliberation on socially responsible innovation than would have been possible if the natural and social scientist had not known one another.

Concluding Remarks and Recommendations

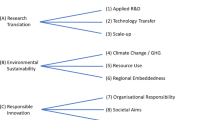

Collaborations between researchers from the natural and social sciences may provide organisations with practical means to establish more socially responsible innovation practices. Yet, collaborations in industry appear to be difficult to set up. In this paper we aimed to elucidate the practical implications of setting up and managing collaborations in industrial R&D, between researchers in the natural and social sciences, based on our own experiences in doing so. Our findings are summarised in Fig. 1.

Overview of the authors’ considerations in setting up, creating and working in collaborative spaces pertaining to ourselves as social scientists, the hosting R&D organisation in which our collaborative research was carried out, and our study participants from the natural sciences. We represented collaborative research as DNA: the natural and social scientist retain their own functions (and goals) like the two strands of DNA, yet the many linkages between them enable both to do their work better

We started by illustrating the sensitivities in proposing to conduct collaborative research with the industrial partners. Based on our experiences, we recommend that such proposals be carefully formulated and addressed to people who one knows to be personally interested in the proposed collaborations. We also highlighted the importance of stressing the potential relevance and usefulness of participation for the individual researchers. The small number of articles on collaborations presented in the social sciences literature to date do provide examples of potential personal and organisational benefits which can be considered important by representatives from industry. In our experience, that has been enough to convince industrial partners to participate, but only under the condition that a confidentiality agreement was in force.

In working in collaborative spaces, we recommend that basic knowledge of the natural scientific and technological principles is acquired by the social scientist before engaging in collaborative research. In addition, it is helpful to realise that social and ethical considerations are not integrated in R&D practice overnight. A good relationship between the social and natural scientist facilitates such integration, which can only be established after repeated interaction over time, i.e. for 4–8 weeks in our experience. Natural scientists should be willing to participate without being coerced, and both types of researchers need to interact regularly for both sides’ viewpoints to be made credible and taken seriously. Also, in our opinion, interaction need not necessarily be restricted to formal meetings.

We realise that many factors might contribute to a particular company’s agreement or reluctance to open its doors. Even when all of our considerations and recommendations are taken into account, there is no ‘golden ribbon’ (Penders et al. 2009a) tied to any invitation from industrial R&D workers. Still, we believe that the answer to policy makers’ calls for more responsible innovation practices can indeed be found in collaborative spaces in which researchers from the fields of natural and social sciences collaborate. Whilst their roles and goals may diverge, the natural and social scientist can be considered partners in socially responsible innovation practices: the experience of both actors, combined in collaborative spaces, enriches R&D decision-making processes with considerations of social and ethical aspects. As such, collaborative activities such as Midstream Modulation convert theoretical notions of responsible innovation as suggested in science policies to practical implications on the R&D working floor. The relevance and use of such activities is currently emerging. Yet more research—particularly in private R&D environments—could further highlight the full potential of these activities both on the level of R&D practice and corporate management. The social scientist’s critical outside view, developed in physical proximity to actual R&D work, provides the ideal position for relevant, constructive and useful feedback. We hope that our experiences presented in this paper may inspire others to set up and engage in collaborative activities to further explore the potential of such activities and harness their full potential in promoting socially responsible innovation practices.

Notes

These may include both scientists and engineers from fields of natural sciences. Particularly in fields such as the Life Sciences and Nanotechnology, with specific science and technology areas such as Synthetic Biology, the boundaries between ‘scientist’ and ‘engineer’ seem to have disappeared. As such, we describe in this article the terms ‘researcher’ and ‘natural scientist’ for scientists and engineers in natural scientific fields, in contrast to social scientists, ethicists and humanities scholars, who we refer to as ‘social scientists’.

We explicitly do not want to present this paper as a ‘how to’ for setting up collaborative research activities. Rather, we elaborate on our own considerations, in the hope that these inspire future researchers from both the natural and social sciences to set up or participate in collaborative research.

While the presented experiences and suggestions come from setting up collaborative research activities in industry, some of our considerations may also prove valuable in setting up collaborations in other, not-for-profit research institutes.

This company remains anonymous for reasons of confidentiality.

Readers who aspire to engage in collaborative research endeavours and wish to get more in-depth advice on how to formulate such invitations and confidentiality agreements, are happily invited to contact the authors of this paper.

As such, this situation is somewhat similar to methods in anthropology or action research.

Earlier we commented that we once experienced contacting corporate management to be counterproductive in proposing to set up collaborative research. Nevertheless, endorsement of the collaborative research study by the managers of participating researchers possibly is indispensable for the success of such studies, as we illustrate here.

As such, we have no experience working in coerced collaborative spaces.

Even though one may argue that NEST researchers and social scientists are both ‘researchers,’ these two types of researchers work in different areas of expertise and use dissimilar theory, methods, experiments, etc. Also historically these two types of researchers have been described to live in two different ‘cultures’ (Snow 1959). As such, we do not consider them to work within one ‘community of practice’ as this term originally may indicate.

References

21st Century Nanotechnology Research & Development Act. (2003). Public Law, 108–153. Available at http://olpa.od.nih.gov/legislation/108/publiclaws/nanotechnology.asp.

Aaker, D. A., & Jacobson, R. (2001). The value relevance of brand attitude in high-technology markets. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(4), 485–493.

Barling, A., De Vriend, H., Cornelese, J. A., Ekstrand, B., Hecker, E. F. F., Howlett, J., et al. (1999). The social aspects of food biotechnology: A European view. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 7, 85–93.

Bercovitz, J. E. L., & Feldman, M. P. (2007). Fishing upstream: Firm innovation strategy and university research alliances. Research Policy, 36, 930–948.

Berne, R. W. (2004). Towards the conscientious development of ethical nanotechnology. Science and Engineering Ethics, 10(4), 627–638.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Hong Kong: C&C Offset Printing Co. Ltd.

Burningham, K., Barnett, J., Carr, A., Clift, R., & Wehrmeyer, W. (2007). Industrial constructions of publics and public knowledge: A qualitative investigation of practice in the UK chemicals industry. Public Understanding of Science, 16, 23–43.

Calleja-Lopez, A., & Fisher, E. (2009). Dialogues from the lab: Contemporary Maieutics for socio-technical inquiry. In Proceedings of Society for Philosophy & Technology. University of Twente, The Netherlands, July 7–10, 2009.

Calvert, J., & Martin, P. (2009). The role of social scientists in synthetic biology. EMBO Reports, 10, 201–204.

Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2004). Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research. Gateshead: The Athenaeum Press.

Collins, H. M., & Evans, R. (2002). The third wave of science studies: Studies of expertise and experience. Social Studies of Science, 32(2), 235–296.

Collins, H. M., Evans, R., & Gorman, M. E. (2007). Trading zones and interactional expertise. Studies In History and Philosophy of Science Part A, 38(4), 657–666.

Delgado, A., Kjølberg, K. L., & Wickson, F. (2010). Public engagement coming of age: From theory to practice in STS encounters with nanotechnology. Public Understanding of Science, 20(6), 826–845.

Doorn, N., & Fahlquist, J. N. (2010). Responsibility in engineering: Toward a new role for engineering ethicists. Bulletin of Science Technology Society, 30(3), 222–230.

Doubleday, R. (2004). Political innovation. Corporate engagements in controversy over genetically modified foods. (thesis). London: University College London.

Editorial. (2009). Mind the gap. Nature, 462, 825–826.

European Commission. (2011a). Horizon 2020—The framework programme for research and innovation. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 1–14.

European Commission. (2011b). Analysis part I: Investment and performance in R&D—Investing in the future. Innovation Union Competitiveness report 2011, 41–154. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/research/innovation-union/pdf/competitiveness-report/2011/part_1.pdf. Accessed Nov 1, 2012.

European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies to the European Commission. (2007). Opinion on the ethical aspects of nanomedicine—Opinion No. 21. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/bepa/european-group-ethics/docs/publications/opinion_21_nano_en.pdf. Accessed Nov 1, 2012.

Feldman, M. S., Bell, J., & Berger, M. T. (2003). Gaining access: A practical and theoretical guide for qualitative researchers. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

Fisher, E., & Mahajan R. L. (2006). Midstream modulation of nanotechnology research in an academic laboratory. In Proceedings of ASME international mechanical engineering congress & exposition (IMECE). Chicago, Illinois, 1–7.

Fisher, E., Biggs, S., Lindsay, S., & Zhao, J. (2010). Research thrives on integration of natural and social sciences. Nature, 463, 1018.

Fisher, E., Mahajan, R. L., & Mitcham, C. (2006). Midstream modulation of technology: Governance from within. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society, 26(6), 485–496.

Fisher, E., & Miller, C. (2009). Contextualizing the engineering laboratory. In S. H. Christensen, M. Meganck, & B. Delahousse (Eds.), Engineering in context (pp. 369–381). Palo Alto: Academica Press.

Flipse, S. M., & Osseweijer, P. (2013). Media attention on GM food cases—An innovation perspective. Public Understanding of Science, 22(2), 185–202.

Flipse, S. M., & Penders, B. (2012). Duurzaam en gezond: Geloofwaardig op de markt. In B. Penders, F. Van Dam (Eds.), Ingrediënten van geloofwaardigheid—Goed eten onder loep. The Hague: Boom Lemma publishers.

Flipse, S. M., Van der Sanden, M. C. A., & Osseweijer, P. (2012). Midstream modulation in biotechnology industry—Redefining what is ‘Part of the Job’ of researchers in industry. Science and Engineering Ethics, 1–24.

Galison, P. (1997). Image & logic: A material culture of microphysics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Gaskell, G., Allansdottir, A., Allum, N., Castro, P., Esmer, Y., Fischler, C., et al. (2011). The 2010 Eurobarometer on the life sciences. Nature Biotechnology, 29(2), 113–114.

Genus, A., & Coles, A. M. (2005). On constructive technology assessment and limitations on public participation in technology assessment. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 17(4), 433–443.

Gieryn, T. F. (1983). Boundary-work and the demarcation of science from non-science: Strains and interests in professional ideologies of scientists. American Sociological Review, 48(6), 781–795.

Gorman, M. E. (2002). Turning good into gold: A comparative study of two environmental invention. Social Studies of Science, 32(5/6), 933–938.

Henderson, A., Weaver, C. K., & Cheney, G. (2007). Talking ‘facts’: Identity and rationality in industry perspectives on genetic modification. Discourse Studies, 9, 9–41.

Johnson, D. G. (2007). Ethics and technology ‘in the making’: An essay on the challenges of nanoethics. Nanoethics, 1(1), 21–30.

Leigh Star, S., & Griesemer, J. (1989). Institutional ecology—‘Translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387–420.

Nowotny, H. (2003). Democratising expertise and socially robust knowledge. Science and Public Policy, 30(3), 151–156.

Nowotny, H., Schott, P., & Gibbons, M. (2003). Introduction: ‘Mode 2’ revisited: The new production of knowledge. Minerva, 41, 179–194.

Osseweijer, P., Landeweerd, L., & Pierce, R. (2010). Genomics in industry: Issues of a bio-based economy. Genomics Society and Policy, 6(2), 26–39.

Owen, R., & Goldberg, N. (2010). Responsible innovation: A pilot study with the U.K. Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. Risk Analysis, 30(11), 1699–1707.

Patra, D. (2011). Responsible development of nanoscience and nanotechnology: Contextualizing socio-technical integration into the nanofabrication laboratories in the USA. Nanoethics, 5(2), 143–157.

PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. (2012). Sustainability of biomass in a bio-based economy, 1–22.

Penders, B., Verbakel, J. M. A., & Nelis, A. (2009a). The social study of corporate science: A research manifesto. Bulletin of Science Technology Society, 29(6), 439–446.

Penders, B., Vos, R., & Horstman, K. (2009b). Sensitization: Reciprocity and reflection in scientific practice. EMBO Reports, 10, 205–208.

Radstake, M., Van den Heuvel-Vromans, E., Jeucken, N., Dortmans, K., & Nelis, A. (2009). Societal dialogue needs more than public engagement. EMBO Reports, 10, 313–317.

Schot, J., & Rip, A. (1997). The past and future of constructive technology assessment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 54(2/3), 251–268.

Schuurbiers, D. (2010). Social responsibility in research practice. Engaging applied scientists with the socio-ethical context of their work. Thesis, Delft University of Technology.

Schuurbiers, D. (2011). What happens in the lab does not stay in the lab: Applying midstream modulation to enhance critical reflection in the laboratory. Science and Engineering Ethics, 17(4), 769–788.

Shapin, S. (2008). Who are the scientists of today? Seed magazine 19. Available at http://seedmagazine.com/stateofscience/sos_feature_shapin_p1.html. Accessed Nov 1, 2012.

Smits, R., Leyten, J., & Den Hartog, P. (1995). Technology assessment and technology policy in Europe: New concepts, new goals, new infrastructures. Policy Sciences, 28, 271–299.

Snow, C. P. (1959). The two cultures and the scientific revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stegmaier, P. (2009). The rock ‘n’ roll of knowledge co-production. EMBO Reports, 10, 114–119.

Swierstra, T., & Jelsma, J. (2006). Responsibility without moralism in technoscientific design practice. Science, Technology and Human Values, 31(3), 309–332.

Van de Poel, I. (2000). On the role of outsiders in technical development. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 12(3), 383–397.

Van der Burg, S. (2009). Imagining the future of photoacoustic mammography. Science and Engineering Ethics, 15(1), 97–110.

Van der Burg, S. (2010). Taking the soft impacts of technology into account: Broadening the discourse in research practice. Social Epistemology, 23(3–4), 301–316.

Van Riel, C. B. M., & Fombrun, C. J. (2007). Essentials of corporate communication—Implementing practices for effective reputation management. New York: Routledge.

Von Schomberg, R. (2011). Prospects for technology assessment in a framework of responsible research and innovation. In M. Dusseldorp, & Beecroft R. (Eds.) Technickfolgen abschätzen lehren (pp. 39–62). Bildungspotenziale transdisziplinärer Methoden.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilsdon, J., & Willis, R. (2004). See-through science. Why public engagement needs to move upstream. London: Demos.

Wynne, B. (2007). Dazzled by the mirage of influence? STS-SSK in multivalent registers of relevance. Science, Technology and Human Values, 32, 491–503.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is the result of a research project of the CSG Centre for Society and Life Sciences carried out within the research programme of the Kluyver Centre for Genomics of Industrial Fermentation in The Netherlands at the Delft University of Technology, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Department of Biotechnology, Section Biotechnology & Society (BTS), funded by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI)/Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flipse, S.M., van der Sanden, M.C.A. & Osseweijer, P. Setting Up Spaces for Collaboration in Industry Between Researchers from the Natural and Social Sciences. Sci Eng Ethics 20, 7–22 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-013-9434-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-013-9434-7