Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify and describe published research articles that were named in official findings of scientific misconduct and to investigate compliance with the administrative actions contained in these reports for corrections and retractions, as represented in PubMed. Between 1993 and 2001, 102 articles were named in either the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts (“Findings of Scientific Misconduct”) or the U.S. Office of Research Integrity annual reports as needing retraction or correction. In 2002, 98 of the 102 articles were indexed in PubMed. Eighty-five of these 98 articles had indexed corrections: 47 were retracted; 26 had an erratum; 12 had a correction described in the “comment” field. Thirteen had no correction, but 10 were linked to the NIH Guide “Findings of Scientific Misconduct”, leaving only 3 articles with no indication of any sort of problem. As of May 2005, there were 5,393 citations to the 102 articles, with a median of 26 citations per article (range 0–592). Researchers should be alert to “Comments” linked to the NIH Guide as these are open access, and the “Findings of Scientific Misconduct’ reports are often more informative than the statements about the retraction or correction found in the journals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The status and continuing use of literature affected by scientific misconduct is of concern because of the potential for invalid research to misdirect subsequent research and clinical care [6, 7]. In 1990, Mark Pfeiffer and Gwendolyn Snodgrass [20] described the use of retracted, invalid scientific literature, reporting that compared with a control group, the retraction tag in the MEDLINE database reduced subsequent citation by only about one third. In 1998, John Budd and colleagues [5], reported that retracted publications were still frequently cited even through the retraction was visible in the journal and clearly noted in MEDLINE. Although biomedical science tends to be self-correcting [5, 7], a great deal of time and effort may be required to determine that some research is not valid [6], and still retracted papers continue to be cited in the scientific literature [23, 24].

Journals occasionally report on notorious research integrity violations, summarizing information from scientific misconduct investigations, and noting the affected publications [1, 2, 8–11, 17, 23]. Many other lesser-known cases of fraudulent publications have been identified in official reports of scientific misconduct, yet there is only a small body of research on the nature and scope of the problem, and on the continued use of published articles affected by such misconduct [3, 18, 21].

The purpose of this study was to identify published research articles that were named in official findings of scientific misconduct that involved Public Health Services (PHS)-funded research or grant applications for PHS funding, and to investigate compliance with the administrative actions contained in these reports for corrections and retractions, as represented in PubMed. This research also explored the way in which such corrections are indicated to PubMed users, and determined the number of citations to the affected articles by subsequent authors.

Background

DHHS findings of scientific misconduct

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Office of Research Integrity (ORI) Division of Investigative Oversight is responsible for the review of institutional investigations and findings of scientific misconduct leveled against individuals (named as respondents) working within the PHS, or receiving its extramural support [13, 15, 19].Footnote 1 U.S. federal policy defines scientific misconduct as fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results [16].Footnote 2

Figure 1 outlines the usual process of a scientific misconduct investigation, starting with an allegation from a ‘whistleblower’. When the final report of an institutional inquiry into misconduct deems that the allegation of scientific misconduct has been substantiated, the ORI issues a “Finding of Scientific Misconduct” report, which is published in its Annual Report, and also in the NIH Guide to Grants and Contracts. These reports usually specify administrative actions against the respondents. Routine administrative actions include debarment from applying for PHS funding or participating in study sections for a period of time [4], and notifying editors of any published articles determined to be fraudulent, plagiarized and/or in need of some type of correction, or directing the respondents to make such notifications [15].

Overview of how a published article comes to be named in a “Finding of Scientific Misconduct” report, and whether it is tagged as corrected or retracted in the MEDLINE database. aRequirements: Correction, errata, or retraction are labeled and published in citable form and in an issue of the journal that originally published the correction or retraction [25]

The problem of correcting the scientific record

Even when the “Findings of Scientific Misconduct” report identifies publications affected by the misconduct, a variety of factors can impede the tagging of the affected article with an erratum or retraction. The National Library of Medicine (NLM) policy for tagging articles with corrections states that notices of errata and retractions will be linked to articles indexed and available on its online PubMed database only if the journal publishes the errata or retraction in a citable form. The citable form requirement stipulates that the errata or retraction is labeled as such, and is printed on a numbered page of the journal that published the originally article. The NLM does not consider unbound or tipped error notices,Footnote 3 and for online journals, only considers errata listed in the table of contents with identifiable pagination [12, 22, 25].

Debra Parrish [23] has described the apparent reluctance of some journals to retract articles. Moreover, the format of retractions may not meet the above NLM requirements. Varying journal policies also confound the process of publishing notices of errata or retractions [3, 7, 10]. In a 2002 survey of journal retraction policies, Michel Atlas [3] noted one participant who stated that his journal did not publish retractions. Some journals allow one author to retract an article, but other journals require that every coauthor consent to the retraction [3, 22]. Fear of litigation is behind the inaction in some cases [7, 14, 22]. Thus, for such myriad reasons, some faulty articles affected by scientific misconduct remain untagged with notices of erratum or retraction.

Methods

Overview of data collection

In 2002, we conducted a content analysis of all the “Findings of Scientific Misconduct” published in two public sources (the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts, and the ORI Annual Reports) from 1991–2001. From these reports we abstracted the information on the publications said to be affected by scientific misconduct, the administrative actions taken against the respondent, and whether the respondent was described as accepting or denying responsibility for the misconduct. We then searched PubMed for the identified articles to determine if subsequent notices of erratum or retraction were added to the citations in PubMed, and if so, the location of such notices. Finally, we used the Web of Science to determine the number of citations others made to these affected articles.

Details of data collection

As described in detail below, the study data were collected from the following four sources: (1) the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts “Findings of Scientific Misconduct” (http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/index.html); (2) the ORI Annual Reports (http://ori.dhhs.gov/publications); (3) the National Library of Medicine’s PubMed online bibliographic database (http://www.pubmed.gov); and (4) Thomson’s Institute for Scientific Information Web of Science bibliographic databases (http://isi02.isiknowledge.com/portal.cgi/).

ORI annual reports and NIH Guide

There was considerable overlap in the information found in the ORI Annual Reports and the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts, “Findings of Scientific Misconduct”. The ORI Annual Reports named only a few articles that were not listed in the NIH Guide. Information abstracted from these sources included:

-

The complete citation of the article affected by misconduct. In a few cases, the report did not include the article title or journal name, merely indicating in a non-specific statement that a published article had been affected by fabrication of data or subjects, falsification of methods or results, or plagiarism (FFP); in such cases, the specific publication citation to these articles was obtained by calling the staff at the ORI.

-

Statements about how the misconduct affected the published article (i.e. FFP).Footnote 4

-

Whether or not the author accepted or denied responsibility for the misconduct (if mentioned in the report).

-

The administrative actions pertaining to the affected article. These usually took the form of debarment from receiving PHS funding, or prohibition from service on PHS advisory or review committees or as a consultant for a specified period of time. For the purpose of this study, we were most interested in whether the administrative action indicated that a specific published article should be retracted or corrected.

PubMed

The PubMed database provided the following information:

-

The article’s unique identifier number (PMID).

-

The citation information of the affected article (i.e., authors, title, journal issue etc.).

-

Whether the citation of the affected article was linked to an additional notice of a retraction, correction or other type of corrigenda, such as in a “Comment” field.

-

The location of any such corrigenda (e.g. as part of the article citation, in a linked field, or on a subsequent linked PubMed webpage).

-

Whether the article had a link to the “Finding of Scientific Misconduct” in the open-access NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts.

Web of science

Data collection from the ISI Web of Science was repeated two times during 2003, and once during 2004 to refine the data collection methodology. Because citations increase over time, a final citation analysis was conducted during the week of May 17, 2005 and the citations as of that week are reported here. This allowed for a minimum period of 3 years between the publication of an affected article and the cut-off date for the citation analysis. The ISI Web of Science database provided the following information:

-

The number of citations for each of the 102 affected articles (“Times Cited”) was identified through the Science Citation Index Expanded databases (SCI-EXPANDED 1980—present, and Social Sciences Citation Index 1980—present). The results may have included self citations.

-

The articles that cited the 102 articles affected by scientific misconduct. The “Times Cited” link provides a list of articles that have cited the affected article. These articles were downloaded into the Endnote software to establish the specific citing articles as of the 5/17/2005 cut-off date.

Results

Implicated researchers and publications

A search of the NIH Guide for “Findings of Scientific Misconduct” of the period from 1991 to 2001 revealed that the first listing of an article affected by misconduct appeared in a 1993 NIH Guide. Between 1993 and 2001, 102 published articles were named in either an NIH Guide or an ORI Annual Report as needing retraction or erratum (see listing of these articles in the Appendix). Most of these 102 articles were listed in the NIH Guide (Table 1); only seven of 102 articles were identified exclusively in the ORI Annual Reports. Forty-one researchers were named as responsible for the scientific misconduct that affected these 102 articles. As Table 2 indicates, the scientific misconduct of 22 of 41 respondents were said to have affected two or more published articles; the remaining 19 respondents were responsible for one affected article.

Nature of the misconduct

The nature of the misconduct specified in either the NIH Guide or the ORI Annual Report is presented in Table 3. Most frequently, the misconduct involved fabrication, falsification or misrepresentation of the study results (79 of the 102 articles). In 16 articles, the study methodology was falsely reported. Study subjects were fabricated in five articles, and plagiarism occurred in two.

Accepting responsibility for misconduct

The “Findings of Scientific Misconduct” final reports often included brief statements about whether the implicated researcher/author acknowledged and accepted responsibility for the misconduct. Table 4 shows that 23 of 41 individuals accepted responsibility for the misconduct which affected 53 publications. Five respondents reportedly denied responsibility, or disagreed with the findings of the scientific misconduct investigation. The remaining 13 reports of scientific misconduct findings did not include statements about whether the respondents’ accepted or denied responsibility for the misconduct (generally, the earlier reports were less likely to contain this information).

Prescribed corrections to affected publications

The administrative actions included in the ‘Finding of Scientific Misconduct’, usually stated if an affected article should be corrected or retracted. Table 5 shows that the reports indicated that the corrigenda was already published for 32 of the 102 articles, and “in press” for another 16.Footnote 5 The misconduct report indicated that a retraction or correction was still needed for 47 articles. For the remaining seven articles, the finding of misconduct report did not state whether a correction or retraction was needed.

Nature of corrections in PubMed

We investigated compliance with administrative actions for corrections and retractions to determine which of the 102 affected articles were tagged as corrected or retracted, the location of such corrigenda on the citation’s PubMed webpage(s), and the extent to which these actions might be apparent to PubMed database users.

As of May 2005, 98 of the 102 affected articles were found in PubMed (see Table 6). Eighty-five of these 98 articles had indexed corrections: 47 had a retraction; 26 had an erratum; and 12 had pertinent information in the PubMed “Comment” field. Although there was no notice of corrigenda for the remaining 13 articles, 10 had an open access link to the NIH Guide “Findings of Scientific Misconduct” that indicated the article was affected by misconduct. This left only three articles (A5, A24 and A91 in the Appendix) without any type of indication of an erratum or a retraction, or of the misconduct investigation (i.e. no link to an NIH Guide, to a journal correction, or to a revealing “Comment”).

Full access to corrections

The open-access links to the NIH Guide “Findings of Scientific Misconduct” provide the researcher with an official report about the nature of the misconduct investigation, the final determination as to whether the allegations were supported, and the specific articles affected by scientific misconduct, and the administrative actions for the affected articles. PubMed had open access links to the related NIH Guide for 67 of the 98 articles found in the PubMed database. However, this varied by type of correction: 72% of the 47 retracted articles had a link to the NIH Guide “Findings of Scientific Misconduct”, compared with 81% of the 26 articles with erratum, and only two of the 12 articles with a correction indicated in the “Comment” field.

We also explored the access permitted by our university’s journal subscriptions to the information published in the journals about the retraction or corrigenda for the 102 articles. Using our library subscriptions, we had full access to the journal correction for 36% of the 47 retractions; 23% of the 26 errata, and 40% of the 12 comment corrections. As journal subscriptions vary across institutions, so will researcher access to such detailed information. Although this study was conducted at a Carnegie I Research Institution, the generalizability of this level of access is unknown, and will vary for other researchers.

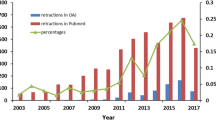

Citations to affected articles

As of the week of May 17, 2005 (the cut-off date for the accumulation of citations), the Web of Science database listed 5,393 citations to the 102 articles. The distributions of citations by type of corrigenda are illustrated in Fig. 2. Table 6 shows that the 102 affected publications had an overall median of 26 citations per article (range 0–592). The 13 articles without a linked corrigendum had a median of 36 citations. The retracted articles had a median of 27 citations; the articles with erratum had a median of 33 citations; and the articles with only a correction found in the “Comment” field had a median of 18 citations.

Number of journal articles that cite 102 articles affected by scientific misconduct (as of the week of 05/17/2005) by presence and type of corrigenda.a

aLower and upper edges of each box represent the 25th and 75th centiles of observed data. The line partitioning box corresponds to median observation. Whiskers include all observations lying within 1.5 times the interquartile range. Dots indicate observations beyond the whiskers

Discussion

The goal of this study of the occurrence and nature of corrections to published articles affected by misconduct was to explore the complex dynamics of biomedical communication [6] as related to correcting the literature affected by misconduct. A content analysis methodology identified all of the 102 published articles named in the final reports of scientific misconduct investigations from 1993–2001. We examined the PubMed database to determine if these articles had links to corrections or retractions, as per the administrative actions in these reports. Close examination of the PubMed web-pages associated with each article revealed how corrections, retractions and findings of scientific misconduct are indicated to database users. Finally, we considered the pattern of citations to these affected articles by their correction status.

The study methodology allowed citations to accrue for a minimum of 3 years after publication of the article affected by scientific misconduct (most but not all of which were tagged with notices of erratum or retraction). This methodology is not directly comparable to other studies reporting on citations to retracted articles. Pfeiffer and Snodgrass [20] defined post-retraction citations as those occurring in the next calendar year, and thus had only a six-month average washout period for citing articles already in the publishing process at the time of the retraction. Budd and colleagues [5] provided for a one-year period after publication of a retraction to allow time for its indexing before a citation was considered as post-retraction. Since the time lag from initial manuscript submission to publication can frequently take up to 12 months (or more), it is reasonable to assume that authors who cite articles affected by misconduct would be unlikely to know that an article was retracted or corrected, if such notices were inserted around the time of their manuscript submission. Our three-year time lag before accumulating citations provides a larger window to assume that subsequent citing authors could be expected to know about an article affected by misconduct.

Only 41 authors, responsible for 102 published articles, were named as respondents in these final reports of scientific misconduct investigations. When searching the PubMed database, an indication of some type of corrigendum (i.e. a retraction, erratum or correction in the “Comment” field) was identified for almost all of these articles. For the majority, the affected article was tagged as retracted or with an erratum. However, for some articles, the information was found on a subsequent webpage, either through links to an unlabeled “Comment”, or to a “Finding of Scientific Misconduct” in the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts. Either an indexed correction (including “Comments”) or a link to the open-access NIH Guide was available for 95 of 98 articles indexed in PubMed.

While indexing errata and retractions in PubMed is essential to alert users to published articles affected by misconduct, full access links to the NIH Guide, or to a journal’s statements about the corrections, can help users determine the nature of erroneous information contained in an article affected by misconduct. Oftentimes the journal’s statements contained different information about the scientific misconduct than what was found in the indexed PubMed correction. Full access to both these sources is ideal because a researcher can compare the administrative actions in the NIH Guide’s “Findings of Scientific Misconduct” with the indexed journal corrections, thereby making an informed decision about the validity of the information in question. For example, five articles (A15, A41, A50, A83, and A99 in the Appendix) were corrected instead of retracted as prescribed in the administrative actions of NIH Guide “Finding of Scientific Misconduct”. Another article (A16) had a retraction tag in PubMed, but then had links to two errata (not retractions).

Limitations

Data collection for this study started in 2002, when the 102 published articles were identified from the official reports of scientific misconduct investigations, and first searched in the PubMed database. During 2003, the study database and data collection methodology was twice reviewed and verified. A final determination of the status of the 102 articles in PubMed was made during the week of May 17, 2005. Thus, the status of articles was checked four times over the course of the study. During these repeated inspections of the PubMed database, the dynamic nature of this wonderful resource became apparent. In particular, during 2003 several articles had newly linked postings to the NIH Guide “Findings of Scientific Misconduct”, compared to the initial 2002 data collection. Recognizing that the database is periodically updated, we reviewed and updated our study database in May 2005 so that the most current data possible is presented here.

The dates that retractions or errata or links to the NIH Guide were posted in the PubMed database are not provided. Thus, it is not clear that these elements were present at the time that a particular user cited the flawed article with a corrigendum or a link to the NIH Guide. In addition, although PubMed provides links to the open-access NIH Guide, it is not known if researchers actually use these links, and thereby learn the details of the scientific misconduct and associated administrative actions related to these articles.

Conclusion

Many links to the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts “Findings of Scientific Misconduct” were posted years after the misconduct finding, if at all: 31 of 98 affected articles indexed in PubMed had no link to the public NIH Guide. Over the course of the study, the PubMed data base added links to the NIH Guide for several articles in the study population, making it easier for current researchers and database users to be aware of the problems with articles affected by scientific misconduct. However, it appears that the thousands of researchers who cited the 102 articles affected by misconduct were unaware of the finding of misconduct, and did not notice the retraction and erratum tags that were in place for most. Similarly, others have noted the continuing use of retracted literature [5, 6, 17, 20, 23, 24].

Most journals are not open access and on-line availability of corrections in the PubMed “Comment” is determined by institutional subscriptions, making it difficult for some to learn more about the particular details related to the corrigenda. Researchers should be alert to “Comments” linked to the open-access NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts, as its “Findings of Scientific Misconduct” usually provide the most detail about the nature of the problem in the affected articles and are often more informative than the statements about the retraction or correction found in the journals (which do not always reveal that the article was affected by scientific misconduct).

How can the continued citation of research affected by scientific misconduct be reduced? More prominent labeling in the PubMed database is desirable to alert users to notices of retraction and errata. This could take the form of larger or bold fonts for these notices. In addition, a prominent placement of the word “retraction” on the first page of such articles would be useful, because once a user downloads an article, these notices are left behind. Harold Sox and Drummond Rennie [23] recently delineated the responsibilities of institutions, editors and citing authors for preventing the continued citation of fraudulent research. Included among their recommendations are two that are particularly pertinent here: (a) authors submitting manuscripts for publication are charged with the responsibility to check each reference cited in their bibliography to see if it has been retracted; and (b) authors (or readers) who discover a published article contains a reference to a retracted article are responsible for submitting a correction to the journal [23].

Notes

Before 1986, reports of scientific misconduct were received by funding institutes within the PHS agencies. Attempts to create a central locus for scientific misconduct lead to the formation of the Institutional Liaison Office. In 1989, the Public Health Service created the Office of Scientific Integrity (OSI) in the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, and the Office of Scientific Integrity Review (OSIR) in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH), for the sole purpose of dealing with scientific misconduct. In 1992, the offices were combined to form the Office of Research Integrity (ORI) in the OASH. In 1993, the ORI was established as an independent entity within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Organizationally, the ORI is located within the Office of the Secretary of HHS in the Office of Public Health and Science which is headed by the Assistant Secretary for Health. [15]

A finding of scientific misconduct requires that: (a) there be a significant departure from accepted practices of the relevant research community; and (b) the misconduct be committed intentionally, or knowingly, or recklessly; and (c) the allegation be proven by a preponderance of evidence [16].

Usually a small piece of paper (e.g. 5′′ × 8′′ approximately) inserted into the journal to report an erratum or retraction that is not bound into the permanent journal issue.

In some cases, the finding of misconduct was published years after an affected article was published, and the report indicated that a retraction or correction had already been posted.

In some cases, the finding of misconduct was published years after an affected article was published, and the report indicated that a retraction or correction had already been posted.

References

Anderson, A. (1988). First scientific fraud conviction. Nature, 335, 389.

Angell, M., & Kassirer, J. P. (1994). Setting the record straight in the breast-cancer trials. New England Journal of Medicine, 330, 1448–1450.

Atlas, M. C. (2004). Retraction policies of high-impact biomedical journals. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 92, 242–250.

Bonetta, L. (2006). The aftermath of scientific fraud. Cell, 124, 873–875.

Budd, J. M., Sievert, M., & Schultz, T. R. (1998). Phenomena of retraction: Reasons for retraction and citations to the publications. Journal of the American Medical Association, 280, 296–297.

Budd, J. M., Sievert, M., Schultz, T. R., & Scoville, C. (1999). Effects of article retraction on citation and practice in medicine. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 87, 437–443.

Couzin, J., & Unger, K. (2006). Scientific misconduct. Cleaning up the paper trail. Science, 312, 38–43.

Culliton, B. J. (1983). Coping with fraud: The Darsee case. Science, 220, 31–35.

Engler, R. L., Covell, J. W., Friedman, P. J., Kitcher, P. S., & Peters, R. M. (1987). Misrepresentation and responsibility in medical research. New England Journal of Medicine, 317, 1383–1389.

Friedman, P. J. (1990). Correcting the literature following fraudulent publication. Journal of the American Medical Association, 263, 1416–1419.

Holden, C. (1987). NIMH finds a case of “serious misconduct”. Science, 235, 1566–1567.

Kotzin, S., & Schuyler, P. L. (1989). NLM’s practices for handling errata and retractions. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 77, 337–342.

Marwick, C. (1992). Federal health officials continue to reorganize offices for investigating scientific misconduct. Journal of the American Medical Association, 268, 848.

McCook, A. (2005). Retraction sparks lawsuit. The Scientist, 6, 1012–1021.

Office of Research Integrity. (2006). [website]. Available at: http://ori.dhhs.gov/. Accessed December 6, 2006.

Office of Science and Technology Policy. (2000). Executive Office of the President; Federal Policy on Research Misconduct; Preamble for Research Misconduct Policy. Federal Register, 65, 76260–76264.

Parrish, D. M. (1999). Scientific misconduct and correcting the scientific literature. Academic Medicine, 74, 221–230.

Parrish, D. M. (2004). Scientific misconduct and findings against graduate and medical students. Science and Engineering Ethics, 10, 483–491.

Pascal, C. B. (1999). The history and future of the Office of Research Integrity: Scientific misconduct and beyond. Science and Engineering Ethics, 5, 183–198.

Pfeifer, M. P., & Snodgrass, G. L. (1990). The continued use of retracted, invalid scientific literature. Journal of the American Medical Association, 263, 1420–1423.

Reynolds, S. M. (2004). ORI findings of scientific misconduct in clinical trials and publicly funded research, 1992–2002. Clinical Trials, 1, 509–516.

Schiermeier, Q. (1998). Authors slow to retract ‘fraudulent’ papers. Nature, 393, 402.

Sox, H. C., & Rennie, D. (2006). Research misconduct, retraction, and cleansing the medical literature: Lessons from the Poehlman case. Annals of Internal Medicine, 144, 609–613.

Unger, K., & Couzin, J. (2006). Scientific misconduct. Even retracted papers endure. Science, 312, 40–41.

United States National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health. (2006). Errata, Retraction, Duplicate Publication, Comment, Update and Patient Summary Policy for MEDLINE. Fact Sheet [website]. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/errata.html. Accessed April 11, 2006.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Research on Research Integrity Program, an ORI/NIH collaboration, grant # R01 NS44487.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Bibliography of 102 articles identified in final reports of “Findings of Scientific Misconduct” (from either the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts or the Office of Research Integrity Annual Reports 1993–2001). Respondents named in these findings of scientific misconduct are in bold

A1. | Abbs, J. H., Hartman, D. E., & Vishwanat, B. (1987). Orofacial motor control impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology37: 394–398. |

A2. | Arnold, S. F., Klotz, D. M., Collins, B. M., Vonier, P. M., Guillette, L. J., Jr., & McLachlan, J. A. (1996). Synergistic activation of estrogen receptor with combinations of environmental chemicals. Science272: 1489–1492. |

A3. | Black, J. A., Friedman, B., Waxman, S. G., Elmer, L. W., & Angelides, K. J. (1989a). Immuno-ultrastructural localization of sodium channels at nodes of Ranvier and perinodal astrocytes in rat optic nerve. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing papers of a Biological character 238: 39–51. |

A4. | Black, J. A., Waxman, S. G., Friedman, B., Elmer, L. W., & Angelides, K. J. (1989b). Sodium channels in astrocytes of rat optic nerve in situ: Immuno-electron microscopic studies. Glia 2: 353–369. |

A5. | Blanc, P. D., Cisternas, M., Smith, S., & Yelin, E. (1996a). Occupational asthma in a community-based survey of adult asthma. Chest 109: 56S–57S. |

A6. | Blanc, P. D., Cisternas, M., Smith, S., & Yelin, E. H. (1996b). Asthma, employment status, and disability among adults treated by pulmonary and allergy specialists. Chest 109: 688–696. |

*A7. | Blanc, P. D., Eisner, M. D., Israel, L., & Yelin, E. H. (1999). The association between occupation and asthma in general medical practice. Chest 115: 1259–1264. |

A8. | Blanc, P. D., Katz, P. P., Henke, J., Smith, S., & Yelin, E. H. (1997a). Pulmonary and allergy subspecialty care in adults with asthma. Treatment, use of services, and health outcomes. Western Journal of Medicine 167: 398–407. |

A9. | Blanc, P. D., Kuschner, W. G., Katz, P. P., Smith, S., & Yelin, E. H. (1997b). Use of herbal products, coffee or black tea, and over-the-counter medications as self-treatments among adults with asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 100: 789–791. |

A10. | Chao, J., Jin, L., Lin, K. F., & Chao, L. (1997). Adrenomedullin gene delivery reduces blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension Research 20: 269–277. |

A11. | Clayton, G. M., Dudley, W. N., Patterson, W. D., Lawhorn, L. A., Poon, L. W., Johnson, M. A., et al. (1994). The influence of rural/urban residence on health in the oldest-old. International Journal of Aging & Human Development38: 65–89. |

A12. | Constantoulakis, P., Campbell, M., Felber, B. K., Nasioulas, G., Afonina, E., & Pavlakis, G. N. (1993). Inhibition of Rev-mediated HIV-1 expression by an RNA binding protein encoded by the interferon-inducible 9–27 gene. Science259: 1314–1318. |

A13. | Coon, J. S., Landay, A. L., & Weinstein, R. S. (1987). Advances in flow cytometry for diagnostic pathology. Laboratory Investigation 57: 453–479. |

A14. | Courtenay, B. C., Poon, L. W., Martin, P., Clayton, G. M., & Johnson, M. A. (1992). Religiosity and adaptation in the oldest-old. International Journal of Aging & Human Development 34: 47–56. |

A15. | Cunha, F. Q., Weiser, W. Y., David, J. R., Moss, D. W., Moncada, S., & Liew, F. Y. (1993). Recombinant migration inhibitory factor induces nitric oxide synthase in murine macrophages. Journal of Immunology 150: 1908–1912. |

A16. | Duan, L., Bagasra, O., Laughlin, M. A., Oakes, J. W., & Pomerantz, R. J. (1994). Potent inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by an intracellular anti-Rev single-chain antibody. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America91: 5075–5079. |

A17. | Eisner, M. D., Katz, P. P., Yelin, E. H., Henke, J., Smith, S., & Blanc, P. D. (1998a). Assessment of asthma severity in adults with asthma treated by family practitioners, allergists, and pulmonologists. Medical Care 36: 1567–1577. |

*A18. | Eisner, M. D., Yelin, E. H., Henke, J., Shiboski, S. C., & Blanc, P. D. (1998b). Environmental tobacco smoke and adult asthma. The impact of changing exposure status on health outcomes. American Journal of Respiratory and Clincal Care Medicine 158: 170–175. |

A19. | Elmer, L. W., Black, J. A., Waxman, S. G., & Angelides, K. J. (1990). The voltage-dependent sodium channel in mammalian CNS and PNS: Antibody characterization and immunocytochemical localization. Brain Research 532: 222–231. |

A20. | Friedman, A. J., & Hornstein, M. D. (1993). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist plus estrogen-progestin “add-back” therapy for endometriosis-related pelvic pain. Fertility and Sterility60: 236–241. |

A21. | Friedman, A. J., & Thomas, P. P. (1995). Does low-dose combination oral contraceptive use affect uterine size or menstrual flow in premenopausal women with leiomyomas? Obstetrics and Gynecology85: 631–635. |

A22. | Garey, C. E., Schwarzman, A. L., Rise, M. L., & Seyfried, T. N. (1994). Ceruloplasmin gene defect associated with epilepsy in EL mice. Nature Genetics6: 426–431. |

A23. | Hajra, A., & Collins, F. S. (1995). Structure of the leukemia-associated human CBFB gene. Genomics26: 571–579. |

A24. | Hajra, A., Liu, P. P., & Collins, F. S. (1996). Transforming properties of the leukemic inv(16) fusion gene CBFB-MYH11. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology211: 289–298. |

A25. | Hajra, A., Liu, P. P., Speck, N. A., & Collins, F. S. (1995a). Overexpression of core-binding factor alpha (CBF alpha) reverses cellular transformation by the CBF beta-smooth muscle myosin heavy chain chimeric oncoprotein. Molecular and Cellular Biology15: 4980–4989. |

A26. | Hajra, A., Liu, P. P., Wang, Q., Kelley, C. A., Stacy, T., Adelstein, R. S., et al. (1995b). The leukemic core binding factor beta-smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (CBF beta-SMMHC) chimeric protein requires both CBF beta and myosin heavy chain domains for transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America92: 1926–1930. |

A27. | Herman, T. S., Jochelson, M. S., Teicher, B. A., Scott, P. J., Hansen, J., Clark, J. R., et al. (1989). A phase I-II trial of cisplatin, hyperthermia and radiation in patients with locally advanced malignancies. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics17: 1273–1279. |

A28. | Huang, C. F., Flucher, B. E., Schmidt, M. M., Stroud, S. K., & Schmidt, J. (1994). Depolarization-transcription signals in skeletal muscle use calcium flux through L channels, but bypass the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Neuron13: 167–177. |

A29. | Jiao, S., Gurevich, V., & Wolff, J. A. (1993). Long-term correction of rat model of Parkinson’s disease by gene therapy. Nature362: 450–453. |

A30. | Johnson, M. A., Brown, M. A., Poon, L. W., Martin, P., & Clayton, G. M. (1992). Nutritional patterns of centenarians. International Journal of Aging & Human Development 34: 57–76. |

*A31. | Katz, P. P., Eisner, M. D., Henke, J., Shiboski, S., Yelin, E. H., & Blanc, P. D. (1999). The Marks Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire: Further validation and examination of responsiveness to change. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 52: 667–675. |

A32. | Katz, P. P., Yelin, E. H., Smith, S., & Blanc, P. D. (1997). Perceived control of asthma: Development and validation of a questionnaire. American Journal of Respiratory and Clincal Care Medicine 155: 577–582. |

A33. | Kong, H., Raynor, K., Yasuda, K., Moe, S. T., Portoghese, P. S., Bell, G. I., Reisine, T. (1993). A single residue, aspartic acid 95, in the delta opioid receptor specifies selective high affinity agonist binding. Journal of Biological Chemistry 268: 23055–23058. |

A34. | Kumar, V., Urban, J. L., & Hood, L. (1989). In individual T cells one productive alpha rearrangement does not appear to block rearrangement at the second allele. Journal of Experimental Medicine170: 2183–2188. |

A35. | Kumar, V., Urban, J. L., Horvath, S. J., & Hood, L. (1990). Amino acid variations at a single residue in an autoimmune peptide profoundly affect its properties: T-cell activation, major histocompatibility complex binding, and ability to block experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America87: 1337–1341. |

A36. | Landay, A., Jennings, C., Forman, M., & Raynor, R. (1993). Whole blood method for simultaneous detection of surface and cytoplasmic antigens by flow cytometry. Cytometry14: 433–440. |

A37. | Lee, C. Q., Yun, Y. D., Hoeffler, J. P., & Habener, J. F. (1990). Cyclic-AMP-responsive transcriptional activation of CREB-327 involves interdependent phosphorylated subdomains. EMBO Journal9: 4455–4465. |

A38. | Lee, T. S., Chao, T., Hu, K. Q., & King, G. L. (1989a). Endothelin stimulates a sustained 1,2-diacylglycerol increase and protein kinase C activation in bovine aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications162: 381–386. |

A39. | Lee, T. S., Hu, K. Q., Chao, T., & King, G. L. (1989b). Characterization of endothelin receptors and effects of endothelin on diacylglycerol and protein kinase C in retinal capillary pericytes. Diabetes38: 1643–1646. |

A40. | Lee, T. S., MacGregor, L. C., Fluharty, S. J., & King, G. L. (1989c). Differential regulation of protein kinase C and (NA,K)-adenosine triphosphatase activities by elevated glucose levels in retinal capillary endothelial cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation83: 90–94. |

A41. | Lee, T. S., Saltsman, K. A., Ohashi, H., & King, G. L. (1989d). Activation of protein kinase C by elevation of glucose concentration: Proposal for a mechanism in the development of diabetic vascular complications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America86: 5141–5145. |

A42. | Levy-Mintz, P., Duan, L., Zhang, H., Hu, B., Dornadula, G., Zhu, M., et al. (1996). Intracellular expression of single-chain variable fragments to inhibit early stages of the viral life cycle by targeting human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. Journal of Virology 70: 8821–8832. |

A43. | Liburdy, R. P. (1992a). Biological interactions of cellular systems with time-varying magnetic fields. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences649: 74–95. |

A44. | Liburdy, R. P. (1992b). Calcium signaling in lymphocytes and ELF fields. Evidence for an electric field metric and a site of interaction involving the calcium ion channel. FEBS Letters301: 53–59. |

A45. | Lin, K. F., Chao, J., & Chao, L. (1995). Human atrial natriuretic peptide gene delivery reduces blood pressure in hypertensive rats. Hypertension26: 847–853. |

A46. | Lin, K. F., Chao, J., & Chao, L. (1998). Atrial natriuretic peptide gene delivery attenuates hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, and renal injury in salt-sensitive rats. Human Gene Therapy9: 1429–1438. |

A47. | Liu, P. P., Hajra, A., Wijmenga, C., & Collins, F. S. (1995). Molecular pathogenesis of the chromosome 16 inversion in the M4EO subtype of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 85: 2289–2302. |

A48. | Liu, P. P., Wijmenga, C., Hajra, A., Blake, T. B., Kelley, C. A., Adelstein, R. S., et al. (1996). Identification of the chimeric protein product of the CBFB-MYH11 fusion gene in INV(16) leukemia cells. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 16: 77–87. |

A49. | London, J. A. (1990). Optical-recording of activity in the hamster gustatory cortex elicited by electrical-stimulation of the tongue. Chemical Senses15: 137–143. |

A50. | London, J. A., & Wehby, R. G. (1994). Classification of inhibitory responses of the hamster gustatory cortex. Brain Research666: 270–274. |

A51. | MacNeill, C., French, R., Evans, T., Wessels, A., & Burch, J. B. (2000). Modular regulation of CGATA-5 gene expression in the developing heart and gut. Developmental Biology 217: 62–76. |

A52. | Martin, P., Poon, L. W., Clayton, G. M., Lee, H. S., Fulks, J. S., & Johnson, M. A. (1992). Personality, life events and coping in the oldest-old. International Journal of Aging & Human Development 34: 19–30. |

A53. | Matsuguchi, T., Inhorn, R. C., Carlesso, N., Xu, G., Druker, B., & Griffin, J. D. (1995). Tyrosine phosphorylation of p95Vav in myeloid cells is regulated by GM-CSF, IL-3 and steel factor and is constitutively increased by p210BCR/ABL. EMBO Journal14: 257–265. |

A54. | Minturn, J. E., Sontheimer, H., Black, J. A., Angelides, K. J., Ransom, B. R., Ritchie, J. M., et al. (1991). Membrane-associated sodium channels and cytoplasmic precursors in glial cells. Immunocytochemical, electrophysiological, and pharmacological studies. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 633: 255–271. |

A55. | Ninnemann, J. L. (1978). Melanoma-associated immunosuppression through B cell activation of suppressor T cells. Journal of Immunology120: 1573–1579. |

A56. | Ninnemann, J. L. (1980). Immunosuppression following thermal injury through B cell activation of suppressor T cells. Journal of Trauma20: 206–213. |

A57. | Ninnemann, J. L., Condie, J. T., Davis, S. E., & Crockett, R. A. (1982). Isolation immunosuppressive serum components following thermal injury. Journal of Trauma22: 837–844. |

A58. | Ninnemann, J. L., & Ozkan, A. N. (1985). Definition of a burn injury-induced immunosuppressive serum component. Journal of Trauma25: 113–117. |

A59. | Ninnemann, J. L., & Ozkan, A. N. (1987). The immunosuppressive activity of C1q degradation peptides. Journal of Trauma27: 119–122. |

A60. | Ninnemann, J. L., Ozkan, A. N., & Sullivan, J. J. (1985). Hemolysis and suppression of neutrophil chemotaxis by a low molecular weight component of human burn patient sera. Immunology Letters10: 63–69. |

A61. | Ninnemann, J. L., & Stockland, A. E. (1984). Participation of prostaglandin E in immunosuppression following thermal injury. Journal of Trauma24: 201–207. |

A62. | Ninnemann, J. L., Stockland, A. E., & Condie, J. T. (1983). Induction of prostaglandin synthesis-dependent suppressor cells with endotoxin: Occurrence in patients with thermal injuries. Journal of Clinical Immunology3: 142–150. |

A63. | Ozkan, A. N., & Ninnemann, J. L. (1987). Reversal of SAP-induced immunosuppression and SAP detection by a monoclonal antibody. Journal of Trauma 27: 123–126. |

A64. | Paparo, A. A., & Murphy, J. A. (1975a). The effect of STH and 6-oh-dopa on the SEM of the branchial nerve and visceral ganglion of the bivalve elliptio complanata as it relates to ciliary activity. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part C, Toxicology & Pharmacology51: 169–170. |

A65. | Paparo, A. A., & Murphy, J. A. (1975b). The effect of sth on the sem and frequency response of the branchial nerve in mytilus edulis as it relates to ciliary activity. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part C, Toxicology & Pharmacology51: 165–167. |

A66. | Paul, S., Belinsky, M. G., Shen, H., & Kruh, G. D. (1996a). Structure and in vitro substrate specificity of the murine multidrug resistance-associated protein. Biochemistry35: 13647–13655. |

A67. | Paul, S., Breuninger, L. M., & Kruh, G. D. (1996b). ATP-dependent transport of lipophilic cytotoxic drugs by membrane vesicles prepared from MRP-overexpressing hl60/ADR cells. Biochemistry35: 14003–14011. |

A68. | Paul, S., Breuninger, L. M., Tew, K. D., Shen, H., & Kruh, G. D. (1996c). ATP-dependent uptake of natural product cytotoxic drugs by membrane vesicles establishes mrp as a broad specificity transporter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America93: 6929–6934. |

A69. | Poon, L. W., Martin, P., Clayton, G. M., Messner, S., Noble, C. A., & Johnson, M. A. (1992). The influences of cognitive resources on adaptation and old age. International Journal of Aging & Human Development 34: 31–46. |

A70. | Raynor, K., Kong, H., Hines, J., Kong, G., Benovic, J., Yasuda, K., Bell, G.I., Reisine, T. (1994). Molecular mechanisms of agonist-induced desensitization of the cloned mouse kappa opioid receptor. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 270: 1381–1386. |

A71. | Reisine, T., Kong, H., Raynor, K., Yano, H., Takeda, J., Yasuda, K., et al. (1993). Splice variant of the somatostatin receptor 2 subtype, somatostatin receptor 2B, couples to adenylyl cyclase. Molecular Pharmacology44: 1016–1020. |

A72. | Ritchie, J. M., Black, J. A., Waxman, S. G., & Angelides, K. J. (1990). Sodium channels in the cytoplasm of Schwann cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 87: 9290–9294. |

A73. | Rosner, M. H., De Santo, R. J., Arnheiter, H., & Staudt, L. M. (1991). Oct-3 is a maternal factor required for the first mouse embryonic division. Cell64: 1103–1110. |

*A74. | Ross, D. E., Buchanan, R. W., Medoff, D., Lahti, A. C., & Thaker, G. K. (1998). Association between eye tracking disorder in schizophrenia and poor sensory integration. American Journal of Psychiatry 155: 1352–1357. |

A75. | Roy, S. N., Kudryk, B., & Redman, C. M. (1995). Secretion of biologically active recombinant fibrinogen by yeast. Journal of Biological Chemistry270: 23761–23767. |

A76. | Ruggiero, K. M., & Major, B. N. (1998). Group status and attributions to discrimination: Are low- or high-status group members more likely to blame their failure on discrimination? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin24: 821–827. |

A77. | Ruggiero, K. M., & Marx, D. M. (1999). Less pain and more to gain: Why high-status group members blame their failure on discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology77: 774–784. |

A78. | Ruggiero, K. M., Mitchell, J. P., Krieger, N., Marx, D. M., & Lorenzo, M. L. (2000a). Now you see it, now you don’t: Explicit versus implicit measures of the personal/group discrimination discrepancy. Psychological Science11: 511–514. |

A79. | Ruggiero, K. M., Steele, J., Hwang, A., & Marx, D. M. (2000b). “Why did I get a ‘D’?”–the effects of social comparisons on women’s attributions to discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin26: 1271–1283. |

A80. | Schwarz, R. E., & Hiserodt, J. C. (1988). The expression and functional involvement of laminin-like molecules in non-MHC restricted cytotoxicity by human LEU-19+/CD3- natural killer lymphocytes. Journal of Immunology 141: 3318–3323. |

A81. | Shen, H., Paul, S., Breuninger, L. M., Ciaccio, P. J., Laing, N. M., Helt, M., et al. (1996). Cellular and in vitro transport of glutathione conjugates by MRP. Biochemistry 35: 5719–5725. |

A82. | Sherer, M. A. (1988). Intravenous cocaine: Psychiatric effects, biological mechanisms. Biological Psychiatry24: 865–885. |

A83. | Sherer, M. A., Kumor, K. M., Cone, E. J., & Jaffe, J. H. (1988). Suspiciousness induced by four-hour intravenous infusions of cocaine. Preliminary findings. Archives of General Psychiatry45: 673–677. |

A84. | Siddiqui, F. A. (1983). Purification and immunological characterization of DNA polymerase-alpha from human acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta745: 154–161. |

A85. | Simmons, W. A., Leong, L. Y., Satumtira, N., Butcher, G. W., Howard, J. C., Richardson, J. A., et al. (1996). Rat MHC-linked peptide transporter alleles strongly influence peptide binding by HLA-B27 but not B27-associated inflammatory disease. Journal of Immunology156: 1661–1667. |

A86. | Simmons, W. A., Roopenian, D. C., Summerfield, S. G., Jones, R. C., Galocha, B., Christianson, G. J., et al. (1997a). A new MHC locus that influences Class I peptide presentation. Immunity7: 641–651. |

A87. | Simmons, W. A., Summerfield, S. G., Roopenian, D. C., Slaughter, C. A., Zuberi, A. R., Gaskell, S. J., et al. (1997b). Novel hy peptide antigens presented by HLA-B27. Journal of Immunology159: 2750–2759. |

A88. | Simmons, W. A., Taurog, J. D., Hammer, R. E., & Breban, M. (1993). Sharing of an HLA-B27-restricted H-Y antigen between rat and mouse. Immunogenetics38: 351–358. |

A89. | Srinivasula, S. M., Hegde, R., Saleh, A., Datta, P., Shiozaki, E., Chai, J., et al. (2001). A conserved XIAP-interaction motif in caspase-9 and Smac/DIABLO regulates caspase activity and apoptosis. Nature 410: 112–116. |

A90. | Stricker, R. B., Abrams, D. I., Corash, L., & Shuman, M. A. (1985). Target platelet antigen in homosexual men with immune thrombocytopenia. New England Journal of Medicine313: 1375–1380. |

A91. | Sublett, J. E., Jeon, I. S., & Shapiro, D. N. (1995). The alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma PAX3/FKHR fusion protein is a transcriptional activator. Oncogene 11: 545–552. |

A92. | Sun, W., & Chantler, P. D. (1992). Cloning of the CDNA encoding a neuronal myosin heavy chain from mammalian brain and its differential expression within the central nervous system. Journal of Molecular Biology224: 1185–1193. |

A93. | Sun, W., Chen, X., & Chantler, P. D. (1994). Inhibition of neuritogenesis by antisense arrest of the expression of a specific isoform of brain myosin-II. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility15: 184–185. |

A94. | Sun, W. D., & Chantler, P. D. (1991). A unique cellular myosin II exhibiting differential expression in the cerebral cortex. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications175: 244–249. |

A95. | Tewari, A., Buhles, W. C., Jr., & Starnes, H. F., Jr. (1990). Preliminary report: Effects of interleukin-1 on platelet counts. Lancet336: 712–714. |

A96. | Urban, J. L., Horvath, S. J., & Hood, L. (1989). Autoimmune T cells: Immune recognition of normal and variant peptide epitopes and peptide-based therapy. Cell59: 257–271. |

A97. | Urban, J. L., Kumar, V., Kono, D. H., Gomez, C., Horvath, S. J., Clayton, J., et al. (1988). Restricted use of T cell receptor v genes in murine autoimmune encephalomyelitis raises possibilities for antibody therapy. Cell54: 577–592. |

A98. | Weiser, W. Y., Pozzi, L. M., & David, J. R. (1991). Human recombinant migration inhibitory factor activates human macrophages to kill Leishmania donovani. Journal of Immunology147: 2006–2011. |

A99. | Weiser, W. Y., Pozzi, L. M., Titus, R. G., & David, J. R. (1992). Recombinant human migration inhibitory factor has adjuvant activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America89: 8049–8052. |

A100. | Wijmenga, C., Gregory, P. E., Hajra, A., Schrock, E., Ried, T., Eils, R., et al. (1996). Core binding factor beta-smooth muscle myosin heavy chain chimeric protein involved in acute myeloid leukemia forms unusual nuclear rod-like structures in transformed NIH 3T3 cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93: 1630–1635. |

*A101. | Yelin, E., Henke, J., Katz, P. P., Eisner, M. D., & Blanc, P. D. (1999). Work dynamics of adults with asthma. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 35: 472–480. |

A102. | Zhou, M., Sayad, A., Simmons, W. A., Jones, R. C., Maika, S. D., Satumtira, N., et al. (1998). The specificity of peptides bound to human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 influences the prevalence of arthritis in HLA-B27 transgenic rats. Journal of Experimental Medicine 188: 877–886. |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neale, A.V., Northrup, J., Dailey, R. et al. Correction and use of biomedical literature affected by scientific misconduct . SCI ENG ETHICS 13, 5–24 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-006-0003-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-006-0003-1