Opinion statement

After concerns about survival and recovery from peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM), the question commonly asked is, “Is it safe to have another pregnancy?” While important advances have been made in the past decade in the recognition and treatment of PPCM, we still do not know why some apparently recovered PPCM mothers have a relapse of heart failure in a subsequent pregnancy. Knowing that some risk for relapse is always present, careful monitoring of the post-PPCM pregnancy is currently the best way to enable earlier diagnosis with institution of effective evidence-based treatment. In that situation it is reassuring to observe that when a subsequent pregnancy begins with recovered left ventricular systolic function to echocardiographic ejection fraction ≥0.50, even with relapse, the response to treatment is good with much more favorable outcomes. On the other hand, beginning the subsequent pregnancy with echocardiographic ejection fraction <0.50 greatly increases the risk for less favorable outcomes. This article summarizes the current state of knowledge; addresses the important questions facing patients, their families, and caregivers; and identifies the need for a prospective multi-center study of women with post-PPCM pregnancies. The reality is that an estimated 10 % to 20 % of apparently recovered PPCM mothers are going to relapse in a post-PPCM pregnancy; but we do not yet know why. Nevertheless, the lowest risk for relapse is experienced by those who (1) recover to left ventricular ejection fraction 0.55 prior to another pregnancy; (2) have no deterioration of left ventricular ejection fraction after phasing out angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin-receptor blocker treatment following recovery; and perhaps, (3) demonstrate adequate contractile reserve on exercise echocardiography.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM) is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in the USA and still leaves many victims with chronic heart failure requiring continuing medications at the prime of their adulthood [1–4]. After concern for survival and recovery following a diagnosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy, a question commonly asked by both caregivers and patients becomes, “Is it safe to have another pregnancy?” The response to this question is far different now than just a little more than a decade ago because a great deal of progress has been made in the recognition of PPCM and in the effectiveness of current evidence-based treatment. This article describes our current state of knowledge and addresses the most pressing issues faced by PPCM mothers everywhere.

What is the risk for relapse of heart failure in a post-PPCM pregnancy?

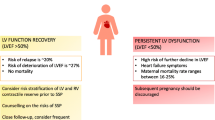

Although there are only limited observations to-date, it is clear that the relapse of heart failure rate in a post-PPCM pregnancy correlates inversely with the level of recovery before the subsequent pregnancy begins [5, 6]. Table 1 lists various series that have been reported and identify relapse of heart failure rates. It is readily apparent that the relapse rate is higher for those who have not yet reached recovery levels of echocardiographic left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥0.50 before a subsequent pregnancy; and that the lower the pre-subsequent pregnancy LVEF, the higher the frequency of relapse of heart failure in the post-PPCM pregnancy. Figure 1 summarizes outcomes for new PPCM patients, identifying those who recover to LVEF ≥0.50 and, therefore, have the lowest risk for relapse of heart failure in a post-PPCM pregnancy. Diagnostic LVEF appears to be a helpful predictor of those who have the greatest potential to recover [13••, 14, 15, 16••].

In a retrospective USA study, Elkayam et al [5], reported that 21 % of recovered PPCM patients (n = 28) experienced a decrease of more than 20 % of LVEF in a subsequent pregnancy compared with 44 % of nonrecovered (n = 16) women. There were no deaths with subsequent pregnancy in the recovered group, but three deaths in the nonrecovered group. Importantly, 14 % of those who entered the post-PPCM pregnancy with recovered level LVEF (≥0.50) but relapsed with the post-PPCM pregnancy still had decreased LVEF at last follow-up compared with 31 % of those who relapsed in the nonrecovered group at beginning of the post-PPCM pregnancy.

In a prospective USA study of post-PPCM pregnancy patients identified through an internet support group, Fett et al [10], reported that one-third of those entering the post-PPCM pregnancy with LVEF 0.50‒0.54 (n = 9) experienced relapse of heart failure; and that 23 % of those entering the post-PPCM pregnancy with LVEF ≥0.55 also experienced heart failure in the post-PPCM pregnancy. Relapse of heart failure rates were progressively worse as the post-PPCM pregnancies began with LVEF < 0.50.

Modi et al [9] reported that 27 % (4/15) of PPCM patients with a subsequent pregnancy experienced relapse or worsening of heart failure with a subsequent pregnancy. There were no maternal deaths, although only four of the 15 entered the subsequent pregnancy with recovered LVEF of ≥0.50. Habli et al [8] followed 21 PPCM patients through a subsequent pregnancy and found that 29 % (6/21) had worsening cardiac function.

Fear of relapse of heart failure in a post-PPCM pregnancy understandably promotes expression of caution about prognosis and outcomes [17]. These concerns are important, but there may be more reasons to be optimistic about risks and outcomes than ever in the past. When beginning the post-PPCM pregnancy with LVEF ≥0.50, even in the presence of relapse, there appears to be no mortality; and subsequent recovery is seen in over 90 % with appropriate recognition and treatment [10]. Early recognition of relapse and institution of appropriate treatment are the key factors in better outcomes. The greatest danger is to those who begin the subsequent pregnancy with lower LVEF, particularly <0.45. Those are the ones who are at higher risk of being left with a worse cardiomyopathy; and in the lowest LVEF onset group, may not survive (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

It must, however, be understood that there can be no guarantee that relapse of heart failure will not occur in a post-PPCM pregnancy. With relapse, even in the most favorable diagnostic and treatment situations, there is a risk that some of those who relapse will end up with a worse cardiomyopathy, and relapse is still a danger to the well-being of the unborn child.

What is the current evidence for “full-recovery” prior to a post-PPCM pregnancy?

Relapse of heart failure in a post-PPCM pregnancy may occur in any subsequent pregnancy; even when it appears that there has been “full recovery.” We define “full recovery” as achievement of systolic heart function to LVEF ≥0.55. There is some evidence that achieving an LVEF ≥0.55 is associated with fewer relapses than for those with LVEF ≥0.50 at the beginning of a subsequent pregnancy [6, 13••, 18].

Other factors, however, are also important. Has there been a return to normal when the remodeling process in recovery has returned to the most pump-efficient ovoid shape compared with the pathologic rounded shape of the left ventricle? Is there any diastolic dysfunction, a common observation in the development of PPCM? Is there any persistent left ventricular dyssynchrony, also a common finding in early PPCM [19]?

Does the current LVEF depend upon a boost from angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) and/or beta blocker (BB) medications? This may be tested by gradual reduction of these medications, carefully observing the LVEF. Slippage in the LVEF would constitute evidence that complete recovery has not yet occurred. If there is a previous history of ventricular tachyarrhythmias, it is prudent to maintain some level of BB treatment “for life.” Indeed, some cardiologists advocate BB treatment “for life” in all recovered PPCM patients.

Why then, do some mothers in a post-PPCM pregnancy relapse with heart failure despite apparent recovery? The answer is almost certainly that they had not actually achieved full recovery prior to the subsequent pregnancy. That is the reason to pursue additional studies in order to try to better understand what “full recovery” means.

Does testing for contractile reserve of the LV provide additional evidence supporting “full recovery?”

Both exercise stress testing and dobutamine stress testing have been advocated to help assess ability to withstand the cardiac stresses of a subsequent pregnancy [2, 6, 10, 19–22]. Dobutamine stress testing adds an additional risk, although small, of adverse reactions. Exercise stress testing has been steadily improving and does not entail any IV injections. If done, the information gained would seem to be limited to those who have reached the LVEF ≥0.55 goal and who have not experienced slippage with weaning off ACEI and BB. Continuation of BB, however, is important for those with any history of ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Table 2 shows the incidence of relapse in post-PPCM pregnancies depending upon LVEF prior to subsequent pregnancy and impact of assessment of contractile reserve.

With the increasing sophistication of exercise echocardiography, it seems reasonable to use it for those who have recovered to LVEF 0.55 and have not experienced deterioration after ACEI/angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB) treatment is gradually withdrawn. Identification of adequate contractile reserve can give additional information about level of recovery but cannot provide any guarantees against potential relapse. Lack of adequate contractile reserve would suggest the need for additional recovery before entering a subsequent pregnancy.

Some advocate additional evaluation of peak CO/O2 consumption on exercise ergonomics as a measure of myocardial capacity and recovery [23]. Additional studies are needed in order to establish what represents “normal” and “recovered” for those determinations. At this time, it is uncertain if this type of testing adds helpful information.

What is the best way to monitor a post-PPCM pregnancy?

There is a very great advantage in monitoring a post-PPCM pregnancy because the patient, her nurses, obstetricians, cardiologists, and primary care givers are already aware of PPCM. With that possibility in mind, the situation is so much easier to monitor. The tools that are available and that have been demonstrated to be helpful are (1) physical examination, (2) periodic self-test for quantification of potential signs and symptoms of heart failure, (3) serial serum B-type natriuretic peptide levels, and (4) periodic echocardiography, with emphasis on following LVEF [18, 23–25, 26••]. If available, it is useful to have a perinatologist familiar with the patient and available for consultation. We do not yet know if it would be helpful to follow serum fms-like tyrosinekinase1 or soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (sFLT1) levels during the pregnancy; although that certainly may become a helpful tool for monitoring the development of severe preeclampsia [27, 28]. It is important to stay alert for the possibility of late onset of heart failure for several months postpartum.

Is there a role for prophylactic beta-blockade in a post-PPCM pregnancy?

We do not know. This has never been subjected to clinical trials in a controlled study. There are advocates for this approach; and there are those cardiologists who recommend it. We are aware of those women in post-PPCM pregnancies that have continued beta-blockade treatment throughout their pregnancy. For most post-PPCM pregnancies in which the pregnancy began with LVEF ≥0.50, there has been no relapse of heart failure; but in some, approximately 10 % to 20 %, there has been a relapse. In those who relapsed, did the presence of BB delay the recognition of that failure? In those who relapsed, did the absence of BB make the relapse more likely? Again, we do not know.

What is the best way to treat relapse of heart failure in a post-PPCM pregnancy if it occurs?

If and when there is a relapse of heart failure in a post-PCM pregnancy, the rate of progression of worsening cardiac function in a post-PPCM pregnancy is unknown; it seems to be variable from rapid to slow, from hours to days to weeks. Once identified, it is important to institute treatment immediately, so as to prevent further deterioration. The treatment of relapse of heart failure in a post-PPCM pregnancy is the same as treatment of the initial episode of heart failure in PPCM, the safety of medication varying if still ongoing pregnancy or breastfeeding [29, 30]. The adage is “follow the Guidelines.”

If the relapse is identified while still pregnant, diuretics and beta-blockers can be safely used with tolerable dosages. On the other hand, ACEI cannot be safely used while still pregnant. Instead, one can safely use hydralazine during pregnancy. The Guidelines lists use of hydralazine as “reasonable if cannot be given ACEI or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARB),” with “Level of Evidence C” (limited populations evaluated and diverging expert opinion).

The combination of hydralazine + nitrates may have a synergistic effect. Hydralazine is an arterial dilator; nitrates are venous dilators. Hydralazine prevents nitrate tolerance and has a strong antioxidant effect; nitrates may blunt the tachycardia that may be seen with hydralazine. Combination use results in increased cardiac output.

Early identification of relapse of heart failure in a post-PPCM pregnancy, permitting early institution of effective treatment is the primary reason why outcomes are so much better than with a first episode of PPCM that has been identified late [10, 25]. This generalization applies to post-PPCM pregnancies that begin with recovered LVEF.

What is the best course to follow if an “unplanned pregnancy” occurs and one is not yet recovered from previous PPCM?

PPCM mothers in the category of “unrecovered” are faced with a great deal of uncertainty and anxiety when faced with this situation. They wonder if it is safe for the unborn child and for them to continue the pregnancy, and fear that their very survival may be in doubt. Some feel that they could not accept a termination of pregnancy. Currently, we cannot identify a lower level of heart function that would define the difference between survival and nonsurvival (Table 2.) Earlier observations suggest that nonischemic cardiomyopathies other than PPCM may tolerate pregnancy better than PPCM [31].

Is one relapse of heart failure in a post-PPCM pregnancy a contraindication to another post-PPCM pregnancy?

We do not know the answer to this question. There have been multiple successful subsequent pregnancies without relapse. There have been relapses on the second subsequent pregnancy, but not in the first. There have been relapses in the first subsequent pregnancy, but not in the second. The most important determining factors in more than one subsequent pregnancy are the same features defining full recovery before another pregnancy as with the first post-PPCM pregnancy.

Conclusions

If one defines “recovery” from PPCM as having heart function LVEF ≥0.50, then the majority of women who have a subsequent pregnancy will not experience a relapse of heart failure. But that is no guarantee. Some will experience a decrease in systolic heart function, a relapse of heart failure. We cannot yet with certainty identify those in this “recovered” category who will relapse. But there have been sufficient observations to know that when the subsequent pregnancy begins with LVEF ≥0.50, and is monitored closely, when and if a relapse begins, the treatment is effective with improved outcomes for both mother and baby. We encourage a prospective multicenter study of post-PPCM pregnancies in order to fill the knowledge gaps existing for the unanswered questions about risk for relapse.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

Pearson GD, Veille JC, Rahimtoola S, Hsia J, Oakley CM, Hosenpud JD, et al. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Office of Rare Diseases (National Institutes of Health) workshop recommendations and review. JAMA. 2000;283:1183–8.

Elkayam U. Clinical characteristics of peripartum cardiomyopathy in the United States: diagnosis, prognosis, and management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:659–67.

Sliwa K, Fett JD, Elkayam U. Seminar: peripartum cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2006;368:687–93.

Fett JD. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: a puzzle closer to solution. World J Cardiol. 2014;6((3):81–114.

Elkayam U, Tummala PP, Rao K, Akhter MW, Karaalp IS, Wani OR, et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes of subsequent pregnancies in women with peripartum cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(21):1567–71. Erratum in: N Engl J Med.2001;345(7):552.

Fett JD, Christie LG, Murphy JG. Outcomes of subsequent pregnancy after peripartum cardiomyopathy: a case series from Haiti. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:30–4.

Sliwa K, Forster O, Zhanje F, Candy G, Kachope J, Essop R. Outcome of subsequent pregnancy in patients with documented peripartum cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1441–3.

Habli M, O’Brien T, Nowack E, Khoury S, Barton JR, Sibai B. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: prognostic factors for long-term maternal outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:415.e1–5.

Modi KA, Illum S, Jariatul K, Caldito G, Reddy PC. Poor outcome of indigent patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:171.e1–5.

Fett JD, Fristoe KL, Welsh SN. Risk of heart failure relapse in subsequent pregnancy among peripartum cardiomyopathy mothers. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2010;109:34–6.

Mandal D, Mandal S, Mukherjee D, Biswas SC, Maiti TK. Pregnancy and subsequent pregnancy outcomes in peripartum cardiomyopathy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:222–7.

pt?>Shani H, Kuperstein R, Berlin A, Arad M, Goldenberg I, Simchen MJ. Peripartum cardiomyopathy—risk factors, characteristics and long-term follow-up. J Perinat Med. 2014.

McNamara DM, Damp J Elkayam U, Hsich E, Ewald G, Cooper LT, et al. Abstract 12898: Myocardial recovery at six months in peripartum cardiomyopathy: results of the NHLBI multicenter IPAC study Circulation. 2013;22 (Suppl). First prospective North American study of new PPCM subjects with important identification of predictors of recovery vs non-recovery.

Goland S, Modi K, Bitar F, Janmohamed M, Mirocha JM, Lawrence SC, et al. Clinical profile and predictors of complications in peripartum cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail. 2009;15:645–50.

Fett JD, Christie LG, Carraway RD, Murphy JG. Five-year prospective study of the incidence and prognosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy at a single institution. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:1602–6.

McNamara DM, Starling RC, Cooper LT, Boehmer JP, Mather PJ, Janosko KM, et al. IMAC Investigators. Clinical and demographic predictors of outcomes in recent onset dilated cardiomyopathy: results of the IMAC (Intervention in Myocarditis and Acute Cardiomyopathy)-2 study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1112–8. Identifies sub-set of 39 PPCM subjects in whom echocardiographic measure of left ventricular remodeling/dilation serves as strong predictor of non-recovery.

Johnson-Coyle L, Jensen L, Sobey A, American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association. Peripartum cardiomyopathy: review and practice guidelines. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21:89–98.

Fett JD. Personal Commentary: monitoring subsequent pregnancy in recovered peripartum cardiomyopathy mothers. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2010;9:1–3.

Tanaka H, Tanabe M, Simon MA, Starling RC, Markham D, Thohan V, et al. Left ventricular mechanical dyssynchrony in acute onset cardiomyopathy: association of its resolution with improvements in ventricular function. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:445–56.

Lampert MB, Weinert L, Hibbard J, Korcarz C, Lindheimer M, Lang RM. Contractile reserve in patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy and recovered left ventricular function. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:189–95.

Pellikka PA, Naqueh SF, Elhendy AA, Kuehl CA, Sawada SG. American Society of Echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography recommendations for performance, interpretation, and application of stress echocardiography. J Am Soc Echjocardiogr. 2007;20:1021–41.

Sicari R, Nihoyannopoulos P, Evangelista A, et al. European Association of Echocardiography. Stress echocardiography expert consensus statement: European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) (a registered branch of the ESC). Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008;9:415–37.

Lang CC, Karlin P, Haythe J, Tsao L, Mancini DM. Ease of noninvasive measurement of cardiac output coupled with peak V02 determination at rest and during exercise in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:404–5.

Blauwet LA, Cooper LT. Diagnosis and management of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2011;97:1970–81.

Fett JD. Earlier detection can help avoid many serious complications of peripartum cardiomyopathy. Futur Cardiol. 2013;9(6):809–16.

Fett JD. Validation of a self-test for early diagnosis of heart failure in peripartum cardiomyopathy. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2011;10:44–5. Identifies simple, inexpensive self-test to help with early identification of heart failure in PPCM subjects; early recognition helps in diagnosis while heart function relatively intact, and therefore recovery more likely.

Rana S, Powe CE, Salahuddin S, Verlohren S, Perschel FH, Levine RJ, et al. Angiogenic factors and the risk of adverse outcomes in women with suspected preeclampsia. Circulation. 2012;125:911–9.

Rana S, Shahul S, Rowe GC, Jang C, Liu L, Hacker MR, et al. Cardiac angiogenic imbalance leads to peripartum cardiomyopathy. Nature. 2012;485:333–8.

American Heart Association. In: Fuster V, editor. The AHA guidelines and scientific statements handbook. Oxford: Wiley; 2009.

European Society of Cardiology. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–847.

Bernstein PS, Magriples U. Cardiomyopathy in pregnancy: a retrospective study. Am J Perinatol. 2001;18:163–8.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Dr. James D. Fett, Dr. Tina P. Shah, and Dr. Dennis M. McNamara each declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Heart Failure

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fett, J.D., Shah, T.P. & McNamara, D.M. Why Do Some Recovered Peripartum Cardiomyopathy Mothers Experience Heart Failure With a Subsequent Pregnancy?. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 17, 354 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-014-0354-x

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11936-014-0354-x