Abstract

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an inflammatory arthritis associated with psoriasis that follows an indolent and progressive course. A delay in diagnosis and treatment may lead to irreversible changes such as erosive arthritis, which lead to permanent physical disability and deformity. Administration of a well-designed screening tool can increase detection of PsA and help determine the prevalence of PsA in a given population. Several tools have been developed to help clinicians screen for PsA. Members of the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis recently led an effort to develop and validate three PsA screening tools: the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation tool, the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, and the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an inflammatory arthritis associated with psoriasis that follows an indolent and progressive course. A delay in diagnosis and treatment may lead to irreversible changes, which then lead to physical disability and deformity [1–4]. Clinical classification criteria have been developed to help identify individuals with PsA [5]; however, application of these criteria requires physical examination. In the context of a busy clinic or in a large epidemiologic study, it may not be possible for an expert clinician to review all patients suspected of having PsA. A screening tool for PsA may help screen a large number of individuals to identify those most likely to have PsA, who could then be promptly referred to a rheumatologist for definitive diagnosis and treatment. A screening tool also could be used in epidemiologic studies to identify probable cases of PsA. To help clinicians and investigators screen for PsA, several screening tools have been developed with varied developmental schema.

Peloso et al. [6] created the 12-item Psoriasis Assessment Questionnaire (PAQ) to detect arthritis among patients with psoriasis. In their study, participants completed the PAQ, and a rheumatologist clinically evaluated those who scored high (≥ 7 of 12) and low (≤ 3 of 12). The PAQ score predicted PsA with 85% sensitivity and 88% specificity at a score cutoff of seven and higher [6]. They concluded that the PAQ was useful in detecting PsA in patients with psoriasis. These results were published in abstract form only in 1997. In 2002, Alenius et al. [7] evaluated the PAQ in a study of the prevalence of joint disease in a hospital and community-based population of 276 individuals with psoriasis. Of these, 202 (73%) completed the PAQ and underwent clinical evaluation, including radiographs for those with joint or axial complaints. Although they found a relatively high prevalence of PsA (48%), they did not find the PAQ to be as sensitive in identifying PsA compared with the first study by Peloso et al. [6]. The best score cutoff of 4 of 8 yielded 60% sensitivity and 62% specificity. Even after modifying the PAQ with weighted questions and scoring, the sensitivity did not improve, although the specificity increased to 73% [7]. Furthermore, Alenius et al. [7] concluded that the PAQ did not discriminate for arthritis in their population of individuals with psoriasis.

Recently, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA), an international collaboration of dermatologists, rheumatologists, epidemiologists, and scientists, led an effort to develop and validate PsA screening tools in addition to the PAQ [8•]. Administration of a well-designed screening tool can not only increase detection of PsA but also help determine the prevalence of PsA in a given population. The critical rationale for a PsA screening tool would be to accelerate a referral to a rheumatologist, not to serve as a substitute for a diagnosis or to compare drug efficacy. Because most PsA patients present initially with skin findings, dermatologists are at a distinct advantage of seeing these patients earlier. Most rheumatologists and dermatologists agree that all psoriasis patients should be screened for PsA; however, the option remains as to which is the best screening tool to use in a specific clinical situation. This article summarizes the recent development and validation of three PsA screening tools: the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation tool (PASE), the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS), and the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST).

Description of Screening Tools

The Psoriatic Arthritis Screening and Evaluation Tool

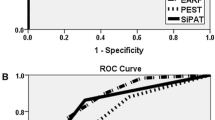

Qureshi et al. [8•] developed and validated the PASE tool at the Center for Skin and Related Musculoskeletal Diseases Clinic, a combined dermatology–rheumatology clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. The PASE was designed for a single purpose: to help dermatologists identify individuals with psoriasis who would benefit from a prompt referral to rheumatology. It was not meant to be used as a diagnostic tool or as a substitute for a thorough rheumatologic examination. The one-page PASE tool is self-administered and consists of 15 questions that are divided into 2 subscales: 7 questions that assess symptoms and 8 questions that assess function. The questions were jointly derived from an expert consensus of dermatologists and rheumatologists and filtered through a Delphi process. The scoring system provides a numeric scale; individuals who are more likely to have PsA will score higher than individuals without PsA. Results of pilot testing in 71 individuals attending the combined Brigham and Women’s Hospital dermatology–rheumatology clinic were analyzed to validate this concept: scores of individuals without PsA (including those with osteoarthritis) were significantly lower than scores of those with PsA (without osteoarthritis). Furthermore, the PASE was able to distinguish severe PsA subtypes (mutilans) from less severe subtypes. A total score cutoff of 47 was able to detect PsA with 82% sensitivity and 73% specificity [9•]. A second validation study in a larger sample size of 190 individuals showed that the PASE was able to distinguish PsA from non-PsA with 76% sensitivity and 76% specificity at a total score cutoff of 44 [10••]. PASE scores may be low in individuals with no active symptoms or whose disease is in remission. Hence, in a subanalysis of the second study, 10 participants whose PsA was quiescent or asymptomatic (based on rheumatologic evaluation) were excluded to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the PASE tool among those with active symptoms only. In these remaining 180 individuals, a total PASE score of 47 yielded a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 80%. The PASE was readministered to a subset of patients and demonstrated significant test–retest reliability and sensitivity to change after systemic therapy [10••]. The PASE has been translated into 12 languages and is being used in more than 15 countries. The PASE questionnaire has been shown to be an efficient tool that clinicians may use to screen individuals with psoriasis for PsA.

The Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen

Gladman et al. [11] sought to develop a PsA screening tool to be used in patients with and without psoriasis: the ToPAS tool. The ToPAS is a two-page questionnaire that contains 12 items, including pictures of psoriatic skin and nail lesions, along with questions about pain and stiffness in the joints and back. Questions were generated from a review of items among patients with PsA, and expert opinion from rheumatologists and dermatologists formed the basis of question selection. Questions were also reviewed by patients for readability and investigators for face validity. In their initial validation study, Gladman et al. [11] administered the ToPAS at five clinical sites in Toronto: clinics for PsA, psoriasis, general dermatology, general rheumatology, and family medicine. A rheumatologist assessed each participant and diagnosed a participant with PsA according to a standard protocol that included a complete history and physical examination, routine laboratory studies, rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear factor. Radiographs were performed only among cases of suspected PsA. Stepwise logistic regression models and receiver operating characteristic curves were performed and revealed high sensitivities and specificities at all clinical sites. A score cutoff of eight yielded an overall sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 93% [12••]. The ToPAS questionnaire was shown to be a tool that can screen for PsA in psoriatic individuals and in the general population.

The Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool

Helliwell et al. [13••] took a combined approach by creating a PsA screening tool based on both the PAQ and the Alenius et al. [7] modification of the PAQ, with the addition of new questions on spondyloarthropathy and dactylitis: the PEST. A picture of a mannequin in which individuals could indicate stiff, swollen, or painful joints was also included in the PEST. For the development and validation study, a combined questionnaire was sent to a community-based sample of individuals with psoriasis diagnosed by a general practitioner or dermatologist. A subset of participants were invited for clinical examination that included a history and a count of swollen, tender, and damaged joints. Indices of spondyloarthropathy and enthesitis were also measured along with rheumatoid factor and C-reactive protein in the blood. Radiographs were only performed in suspected cases of PsA. The sensitivity and specificity for each question were calculated to determine the questions with the most significance. These questions were included in a logistic regression model, which generated five questions that were used in the final version of the PEST. Of the 633 participants who were sent the PEST via postal mail, 168 (27%) responded with a completed questionnaire, 93 agreed to clinical examination, and 12 had PsA according to the CASPAR (Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis). An additional 21 individuals with known PsA from St. Luke’s Hospital Rheumatology Clinic in Bradford, United Kingdom also completed the PEST. Receiver operator curve analysis showed that the PEST screened for PsA with 92% sensitivity and 78% specificity [13••].

Discussion

This article sought to review the development and validation efforts of three screening tools for PsA. To optimize best practices, all psoriasis patients should be screened for PsA to help prevent irreversible joint damage. Survey-type instruments may serve as screening tools and may be used in clinical practice or in epidemiologic studies. In general, screening tools developed for use in clinical practice should be highly sensitive and quick and easy to administer, whereas screening tools for use in research purposes should be highly specific and include more comprehensive data. The properties of an effective screening tool include high sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value; however, a common goal of having a high sensitivity is required so that index cases are not missed. The PASE, ToPAS, and PEST are screening tools that have been developed recently. All three have undergone rigorous methods for validation and possess good sensitivities for screening purposes. Although these questionnaires have been used in slightly different populations with different purposes, they all attempt to identify cases of PsA; however, each offers distinct features (Table 1). For example, the PASE has the ability to monitor a patient’s response to therapy in addition to screening for PsA, perhaps owing to its functional component. Furthermore, the PASE was specifically designed to be used by dermatologists to screen psoriasis patients for PsA in a busy clinical setting. The assumption is made that rheumatologists would not need to have a screening tool to substitute for their advanced training. Thus, PASE does not include psoriasis screening because it is administered to individuals already diagnosed with psoriasis. Psoriasis skin lesions usually precede the onset of joint symptoms by 10 years [14], and because dermatologists manage 95% of psoriasis cases in the United States [15], they are in an ideal position to screen individuals for PsA early. The ToPAS questionnaire, on the other hand, was designed to screen for psoriasis and PsA in the general population and to capture data for epidemiologic studies and family investigations. Another unique feature of the ToPAS is its ability to capture visual data through its picture format. The inclusion of pictures in a screening questionnaire addresses the need to create plain language documents to reach as wide an audience as possible. The PEST tool offers a picture of a mannequin for individuals to indicate areas of joint pain, stiffness, or swelling, allowing for quick identification of problem areas that could facilitate a prompt referral. Each of the questionnaires may benefit from further validation efforts. The ToPAS and PEST may benefit from undergoing validation in large epidemiologic studies. The PASE could serve as a screening tool for clinical purposes; however, it could benefit from undergoing validation in a non–tertiary care referral center, such as a community clinic setting. Currently, the PASE is being tested in a large US-based population and in multicenter clinical trial settings. Efforts are also ongoing in Australia to help validate the PASE tool in a private practice dermatology setting. A head-to-head performance comparison of these tools is currently under way in the United Kingdom in a setting in which unselected cases of psoriasis are given the instruments and subsequently examined by a rheumatologist.

Conclusions

In summary, three survey instruments have been developed recently to screen for PsA, each with unique features and validated in a different patient population. The choice of which screening tool to use may depend on its intended use and the population of interest. The PASE may be best used in a high-volume clinical setting, whereas the ToPAS and PEST may be used in a clinical or epidemiologic setting. Administration of a well-designed screening tool can be beneficial in many ways. It may increase detection of PsA and help determine the prevalence of PsA in a given population. Regardless of which questionnaires are to be used for screening, comprehensive validation efforts in various settings must continue, and critical feedback for all three tools must be elicited from clinicians and investigators.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance, •• Of major importance

Zachariae H: Prevalence of joint disease in patients with psoriasis: implications for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003, 4:441–447.

Mease P, Goffe BS: Diagnosis and treatment of psoriatic arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005, 52:1–19.

Brockbank J, Gladman D: Diagnosis and management of psoriatic arthritis. Drugs 2002, 62:2447–2457.

Gladman DD, Brockbank J: Psoriatic arthritis. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2000, 9:1511–1522.

Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al.: Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006, 54:2665–2673.

Peloso PM, Hull P, Reeder B: The psoriasis and arthritis questionnaire (PAQ) in detection of arthritis among patients with psoriasis. Arthritis Rheum 1997, 40:S64.

Alenius GM, Stenberg B, Stenlund H, et al.: Inflammatory joint manifestations are prevalent in psoriasis: prevalence study of joint and axial involvement in psoriatic patients, and evaluation of a psoriatic and arthritic questionnaire. J Rheumatol 2002, 29:2577–2582.

• Qureshi AA, Dominguez P, Duffin KC, et al.: Psoriatic arthritis screening tools. J Rheumatol 2008, 35:1423–1425. This is an update on the development of screening tools for PsA that was presented during the 2009 GRAPPA annual meeting. It includes feedback from GRAPPA members on what should constitute an effective screening tool.

• Husni ME, Meyer KH, Cohen DS, et al.: The PASE questionnaire: pilot-testing a psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation tool. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007, 57:581–587. This was the first validation pilot study of the PASE questionnaire, jointly developed by rheumatologists and dermatologists, which shows the PASE to be an effective screening tool to identify inflammatory arthritis and to distinguish it from noninflammatory arthritis.

•• Dominguez PL, Husni ME, Holt EW, et al.: Validity, reliability, and sensitivity-to-change properties of the psoriatic arthritis screening and evaluation questionnaire. Arch Dermatol Res 2009, 301:573–579. This was the second validation study of the PASE questionnaire in a larger patient population that showed the PASE to be sensitive to change and to have test–retest reliability.

Gladman DD, Schentag CT, Tom B, et al.: Development and validation of a screening questionnaire for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007, 56(Suppl 9):S798.

•• Gladman DD, Schentag CT, Tom BD, et al.: Development and initial validation of a screening questionnaire for psoriatic arthritis: the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen (ToPAS). Ann Rheum Dis 2009, 68:497–501. This article describes the initial development of the ToPAS questionnaire, a psoriasis and PsA screening tool, and its validation in various clinical settings.

•• Ibrahim GH, Buch MH, Lawson C, et al.: Evaluation of an existing screening tool for psoriatic arthritis in people with psoriasis and the development of a new instrument: the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool (PEST) questionnaire. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009, 27:469–474. This article describes the development and validation of the PEST questionnaire, a PsA screening tool, in a community-based setting.

Gelfand JM, Gladman DD, Mease PJ, et al.: Epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in the population of the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005, 53:573.

Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Cooper JZ: New topical treatments change the pattern of treatment of psoriasis: dermatologists remain the primary providers of this care. Int J Dermatol 2000, 39:41–44.

Alenius GM, Stenberg B, Stenlund H, et al.: Inflammatory joint manifestations are prevalent in psoriasis: prevalence study of joint and axial involvement in psoriatic patients, and evaluation of a psoriatic and arthritic questionnaire. J Rheumatol 2002, 29:2577–2582.

Disclosure

Dr. Gladman has received honoraria and/or grant support from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor Ortho Biotech, Schering-Plough, Wyeth, and Pfizer.

Dr. Mease has received research grants from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Biogen Idec, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor, Genentech, Roche, Wyeth, and Pfizer; has served as a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Biogen Idec, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor, Genentech, Roche, UCB, Wyeth, and Pfizer; and has served as a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Biogen Idec, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor, Genentech, UCB, Wyeth, and Pfizer.

Dr. Husni has served as a consultant for Amgen and Genentech.

Dr. Qureshi has served as a consultant for Amgen and Genentech. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dominguez, P., Gladman, D.D., Helliwell, P. et al. Development of Screening Tools to Identify Psoriatic Arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 12, 295–299 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-010-0113-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-010-0113-2