Abstract

A growing body of evidence suggests that social and vocational interventions effectively enhance social and vocational functioning for individuals with schizophrenia. In this review, we first consider recent advances in vocational and social rehabilitation, then examine current findings on neurocognition, social cognition, and motivation with regard to the impact these elements have on rehabilitation interventions and outcomes. A critical evaluation of recent studies examining standalone treatment approaches and hybrid approaches that integrate components such as cognitive remediation and skills training reveals several ongoing challenges within the field. Greater understanding of the differential impact of various approaches, methods that may increase the magnitude of treatment effects, and the generalization of treatment effects to community functioning are among crucial areas for future research. Overall, these treatments hold promise in improving psychosocial functioning and helping individuals with schizophrenia acquire important life skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a multidimensional disorder involving a complex set of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors that interact to undermine functioning throughout the course of the illness. Up to two thirds of individuals with severe mental illness cannot achieve or maintain basic social roles such as employee, spouse, parent, and integrated member of the community [1•]. The field of psychiatric rehabilitation developed as a result of the need to address the significant psychosocial impairments that individuals with severe mental illness must contend with despite the widespread use of psychopharmacologic treatments [2]. Rehabilitative approaches such as social and vocational skills training involve targeted interventions that aspire for participants to acquire important life skills, thereby reducing existing impairments in social and role functioning [2, 3•]. Although a substantial body of evidence supporting the benefits of psychosocial rehabilitation now exists, treatment approaches and investigations of their efficacy continue to evolve rapidly [3•, 4]. One area of rapid growth has been rehabilitation efforts that focus on cognitive aspects of schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses. This new area of focus has moved rehabilitation efforts beyond social skills and vocational training and into areas that target the day-to-day functioning of individuals dealing with mental illnesses. Driving these new rehabilitation efforts is the recent and growing body of literature surrounding the impact of cognitive deficits—both neurological and social—on individuals dealing with schizophrenia, as well as the promising rehabilitative efforts to address these deficits.

In this review, we begin with a summary of recent research on vocational and social rehabilitation interventions. We then introduce recent efforts to develop and test interventions for cognitive remediation and discuss how they are being linked to social and vocational rehabilitation efforts.

Review of Recent Literature

Vocational Rehabilitation

The significance of work in promoting economic, social, and individual psychological health for people with severe mental illness has been widely established [5, 6]. For example, employment has been associated with higher self-esteem, a reduction in symptoms and hospitalizations, enhanced social functioning, and an overall improvement in quality of life. In addition, unemployment and losses in productivity cost up to 32.4 billion dollars per year in the United States, comprising half of all schizophrenia-related costs [7, 8]. Fewer than 15% of people diagnosed with a severe mental illness are employed, although 70% identify work as a primary goal [9]. The barriers to obtaining and maintaining employment for this population are multifaceted and include factors such as cognitive impairments that interfere with work functioning, psychiatric symptoms and episodes of illness, stigma from employers as well as internalized stigma that undermines self-confidence, and the fear of losing disability benefits [10••, 11].

Although a variety of vocational rehabilitation programs have been developed during the past several decades, the Supported Employment model has consistently demonstrated superior results in helping individuals with mental illness obtain competitive employment in comparison with more conventional vocational approaches [6, 12, 13]. However, a constellation of individual-, organizational-, and policy-level barriers have impeded the widespread implementation and use of this model [10••].

Supported employment programs are designed to help people with psychiatric disabilities identify and assess their strengths and interests, conduct a rapid job search, and receive continued support through the use of ongoing supervision and problem solving during employment tenure [14]. Becker and Drake [14] created the most widely used supported employment model: the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model. The key components of the IPS model are as follows: 1) services are focused on helping consumers obtain their own permanent jobs; 2) eligibility is based on consumer choice. No one who wants to participate is excluded based on factors such as diagnosis, symptoms, substance use, or level of disability; 3) a rapid job search is conducted (as opposed to lengthy pre-employment training or counseling); 4) the program is closely integrated with a psychosocial rehabilitation team approach; 5) services are based on consumers’ individualized preferences as opposed to staff judgments; and 6) ongoing individualized support is provided indefinitely.

In their recent review of evidence-based practices for people with severe mental illness, Bond and Campbell [4] noted that across 12 previous randomized controlled trials, an average of 59% of consumers enrolled in supported employment were competitively employed, compared with 21% in traditional vocational programs. These employment rates were replicated in a recent review of 11 studies specifically examining the IPS model [12]. The authors also found that based on an average of 61% of consumers competitively employed after receiving IPS, about two thirds were employed part-time. As a result, they concluded that the number of hours worked is likely influenced by concerns regarding retaining disability and Medicaid eligibility. Furthermore, despite a rapid job search strategy, the review also revealed an average time of 20 weeks until an initial job placement could be achieved. This finding prompted the authors to conclude that job development strategies are a crucial area in need of further programmatic and research inquiry.

Since the most recent review by Bond et al. [12], several noteworthy studies have increased insight into who may benefit from supported employment and which innovative hybrid approaches may advance the use of this intervention. Killackey et al. [7] recently conducted a controlled study in which 41 people with first-episode psychosis were randomly assigned to IPS plus treatment as usual or treatment as usual alone. Those in the intervention group obtained more jobs, lasted longer in their jobs, worked more hours, and earned more money than their counterparts in the treatment-as-usual condition. It is noteworthy that the employment consultant in this trial was able to provide an intensive level of services based on a caseload of 20 individuals as opposed to the considerably larger caseloads that are often found in mental health settings. This study has significant implications in that it supports the notion that supported employment can be used effectively as an early intervention in psychosis. Most research on vocational interventions for people with severe mental illness has focused on individuals with long-term illness; however, findings from this study indicate that the use of this intervention early on may ameliorate or prevent further decrements in functioning among this population.

Burns et al. [15••] also conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing IPS with general vocational rehabilitation in 6 European centers with 312 participants. Importantly, they found that outcomes related to symptoms and functioning improved for both groups when participants returned to work, but those with higher levels of social impairment showed greater improvement in the IPS condition. These findings suggest that IPS may be delivered to more severely impaired populations without restrictions and with a reasonable expectation of positive results. Similarly, Twamley et al. [13] compared IPS with a conventional vocational program for older adults with schizophrenia. Based on a randomized controlled trial, the authors found that 57% of IPS recipients obtained competitive work, compared with 27% of the conventional program recipients. These studies highlight the notion that the collaborative and individualized approach inherent to the IPS model may provide a benefit in meeting the needs of various subpopulations among those with severe mental illness.

Social Rehabilitation

Another prominent feature of schizophrenia is persistent and debilitating impairments in social relationships [3•, 16••]. These deficits in social functioning often result in disrupted relationships with family and peers, difficulty achieving basic social roles, and social exclusion. Social skills training seeks to address the social impairments that characterize schizophrenia with strategies that are founded on the application of social learning principles [17]. Past reviews and meta-analyses examining the impact of social skills training have yielded mixed results for the intervention [18, 19]. Several factors likely have contributed to confusion regarding the efficacy of this approach, including a lack of methodologic rigor in older studies and a lack of consensus regarding appropriate outcome measures [3•]. In addition, a diverse range of strategies have been implemented in various studies that may incorporate components such as vocational skills training, social milieu training, self-care skills, communication skills, and assertiveness training [17, 20, 21].

The lack of research examining whether an increase in social skills after treatment is related to wide-ranging functional markers, such as maintaining social relationships in the community and finding and keeping a job, also represents a significant gap in this literature. However, a recent meta-analysis by Kurtz and Mueser [22] evaluating 22 studies of social skills training programs for people with schizophrenia shed some light on the overall utility of this approach. Results indicate that the effect of social skills training is strongest in relationship to proximal domains targeted by the intervention and weakest in relationship to more distal domains. More specifically, the effects of the intervention on mastery of skills directly implemented in sessions showed a large effect size (d = 1.20), whereas the impact on social and independent living skills and psychosocial functioning showed a moderate effect size (d = 0.52), followed by the impact on negative symptoms (d = 0.40). The impact of social skills training was weakest on the more distal domains of relapse (d = 0.23) and non-negative symptoms (d = 0.15). Because the analysis only included rigorous studies (randomized controlled trials) and effect sizes were computed against active control groups, the robustness of these findings argues convincingly for the utility of social skills training in relationship to functional outcomes overall. However, small effect sizes related to non-negative symptoms and relapse may indicate that determinants influencing these domains are not adequately addressed using this approach alone.

New Developments in Social and Vocational Rehabilitation

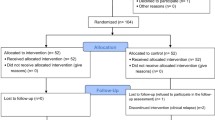

We now examine recent findings on neurocognition, social cognition, and motivation and how they are linked to social and vocational rehabilitation interventions and outcomes. It has long been established that the vast majority of people with severe mental illness suffer from significant cognitive impairment [23], including basic aspects of neurocognition and social cognition. Recent evidence also points to the importance that motivational aspects play in the role of engagement into treatment and successful outcomes [24••]. We explore how attention to these issues can lead to improved functional and subjective outcomes, which are important markers of rehabilitation success and recovery [25•]. These four areas and their components are shown in Fig. 1.

Cognitive Rehabilitation

Cognitive-processing deficits are now recognized as being among the most prominent and treatment-refractory aspects of schizophrenia [3•]. These deficits, impacting domains such as attention, speed of processing, learning, working memory, and problem solving, have been consistently associated with reduced long-term functional outcomes, poor quality of life [13, 26, 27], and poor rehabilitation outcomes [28]. Recently, improvement in neurocognition has been strongly linked to improvement in functional outcomes and response to treatment [29••]. To address the neurocognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia as a means of enhancing overall role functioning, a variety of cognitive remediation approaches were developed during the past several years. Most of these programs employ methods that can be described as cognitive-enhancing techniques or compensatory techniques [3•]. Cognitive-enhancing techniques (eg, drill and practice exercises) aim to directly repair cognitive deficits based on research demonstrating the neuroplasticity and lifelong capacity for growth and development of the brain [30]. In contrast, compensatory cognitive training enhances behavioral adaptation based on teaching strategies and contextual cues within the environment to compensate for areas of cognitive impairment [31].

To date, many studies indicate that cognitive remediation enhances cognitive performance [3•, 32] and can generalize to real world functioning, such as work outcomes [33]. A meta-analysis by Szoke et al. [34•] based on 2476 people showed that participants receiving cognitive remediation improved in most cognitive tasks, with the exception of semantic verbal fluency. The greatest effect sizes were evident in memory tests (0.46), with smaller but still significant effect sizes observed in cognitive flexibility and abstraction (0.38) and vigilance and attention (0.35). These findings were recently replicated in improving overall cognitive functioning and verbal learning [33], verbal memory and executive functioning [35••], and mental flexibility [36••].

Although homogeneity of effect sizes across studies and within various cognitive domains is apparent [27, 34•], individual treatment responses show a wide degree of heterogeneity associated with factors such as intervention type, treatment intensity, motivation, level of ability, and age of participants [37, 38]. For example, McGurk and Mueser [37] recently demonstrated that older adults with schizophrenia exhibit less treatment gains from cognitive remediation than their younger counterparts. Additionally, Medalia and Choi [24••] addressed the diversity of cognition treatment aims and approaches that impact the potential success of outcomes as well as how desired outcomes are defined. For example, the authors noted in their recent review of cognitive remediation that cognitive-enhancing techniques often target outcomes based on neural activation in specific brain regions and performance of task-related activities such as memory tasks. Further differentiation of treatment parameters may result from specific training curriculum within this family of interventions. Cognitive-enhancing conditions may vary between a sequential and hierarchical progression of tasks or a parallel approach to training several cognitive domains simultaneously. Curriculum may be implemented within a group or on an individual basis and may be clinician led or primarily computer based. Currently, the lack of evidence examining the differential impact of various approaches in comparison to one another constitutes a major gap in understanding the utility and limitations of cognitive remediation.

The most recent investigations of cognitive remediation help illuminate the impact of combined interventions that integrate remediation with other therapies [33, 39] versus standalone approaches [40], as well as provide support for previously tested approaches through replication studies [33, 41]. Silverstein et al. [39] examined the impact of attention shaping, a reward-based learning procedure, in combination with the UCLA Basic Conversation Skills Module for participants with schizophrenia. Compared with those who received the standard format conversation skills module alone, individuals in the combined approach demonstrated a significantly improved capacity for sustained attention and higher levels of skill acquisition. Fisher et al. [40] investigated a standalone method of improving verbal memory for individuals with schizophrenia who were randomly assigned to computerized auditory training or a control computer game condition. Relative to the control group, participants in the treatment group showed significant gains in global cognition, verbal working memory, and verbal learning and memory. In addition, support for methods such as computerized cognitive remediation treatment has been strengthened based on recently replicated results across many studies with different therapists, locations, and samples [33, 41].

Two studies differ from most recent investigations with regard to the testing of compensatory strategies as opposed to the more commonly used cognitive-enhancing techniques. Velligan et al. [42] conducted a rigorous examination of a cognitive adaptation approach involving the use of environmental supports such as signs, checklists, and alarms to cue behavioral routines in the home. Results indicated that medication adherence and community functioning significantly improved for respective treatment conditions as compared with treatment as usual. However, whereas effects on medication adherence remained significant at follow-up even after home visits were withdrawn, improvements in functional outcomes were no longer statistically significant once home visits were withdrawn. Twamley et al. [13] also tested a compensatory strategy based on internal prompts (eg, imagery and acronyms) and environmental supports (eg, writing down information) in a randomized controlled pilot study. The authors found that the intervention was associated with significant improvements in cognition and also extended beyond cognitive domains to enhance overall functional capacity and quality of life.

Studies within the past year on cognitive remediation support the notion that this approach improves cognition and aids in the acquisition of important life skills. Current cognitive remediation methods vary in the degree to which they target narrow goals related to cognitive performance as opposed to broader aims related to overall role functioning. Many questions remain unanswered, such as which individual characteristics may account for positive outcomes and how ecologically valid effect sizes are with regard to translating outcomes into community functioning. However, a great deal of evidence supports the conclusion that cognitive remediation can substantially impact the cognitive deficits characteristic of schizophrenia.

Social Rehabilitation and Social Cognition

Another prominent feature of schizophrenia is persistent and debilitating impairments in social relationships [3•, 16••]. These deficits in social functioning often result in disrupted relationships with family and peers, difficulty achieving basic social roles, and social exclusion. Researchers have identified some of the major cognitive domains associated with social dysfunction (eg, deficits in attention and memory), and several cognition remediation methods have successfully targeted these areas [33, 41]. However, despite advancements in cognitive training and psychopharmacologic intervention, these approaches typically account for about 20% to 40% of the variance in functioning-oriented treatment outcomes [16••]. Clearly, further determinants of functional outcome must be identified. A growing body of evidence suggests that social cognition serves as a distinct determinant affecting real world functioning for people with schizophrenia [3•, 16••].

Social cognition is a complex construct representing the mental processes underlying social interactions [43••]. These processes include the ability to generate internal representations of one’s relationship to others and to accurately perceive and interpret the intentions, dispositions, and emotions of others. Thus, people with schizophrenia often misperceive social cues and have difficulty communicating effectively in interpersonal relationships [16••]. Research on the relationship between social cognition and functioning has prompted the identification of four underlying domains that are impaired for individuals with schizophrenia:

-

1.

Emotion processing, which refers to the ability to identify and understand emotions as well as manage them [16••, 44]. One component of emotion processing frequently targeted in rehabilitation treatments is emotion perception, defined as the ability to infer emotional information from cues such as facial expression and voice inflection [45]

-

2.

Social perception, including the ability to evaluate social cues based on contextual information and nonverbal communication, as well as an awareness of social roles and norms that typically guide social interactions [16••]

-

3.

Attributional style, which represents how individuals typically explain the causes of positive and negative events and experiences in their lives (eg, persecutory delusions) [16••]

-

4.

Theory of mind, which involves the ability to understand hints, deceptions, false beliefs, humor, metaphors, and irony (eg, detecting sarcasm) [16••].

Surprisingly, these deficits are found throughout the course of the illness in acutely symptomatic and remitted patients [46]. The rationale for social rehabilitation is based on research demonstrating that the four domains previously mentioned have been associated with various indices of functioning, such as community functioning, quality of life, and social competence [47]. In addition, there is widespread agreement that although social cognition is related to neurocognition, it represents a distinct construct that uniquely contributes to functional outcome [16••, 26, 48]. Some debate has occurred as to whether social cognition should be viewed from a cognitive deficit model or a cognitive bias perspective [49••]. For example, meta-cognitive training for schizophrenia patients, an eight-session group intervention, is aimed at increasing awareness of bias inherent in symptoms such as delusions and instructing participants to reflect critically on these thought patterns to alter behavioral responses. A previous study of inpatients receiving this intervention showed improvements in social intelligence, emotion perception, and theory-of-mind measures [50]. Additionally, a recent randomized controlled pilot study of the intervention demonstrated the feasibility and positive attitude of participants toward the intervention [51]. Although this approach may hold promise, to date, there is a paucity of evidence related to this line of research, with most treatment approaches incorporating a deficits-based focus.

A remediation-style approach to modifying deficits in social cognition can be further divided into two major categories: targeted intervention approaches that attempt to modify a single social cognitive domain and broad-based interventions that target multiple domains of social cognition [49••]. One of the earliest targeted approaches was developed by Penn and Combs [52], who established an intervention focusing on affect recognition. Their work was partially based on previous research associating impairments in attention with deficits in affect recognition [53]. In a recent study by Combs et al. [54•], participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: attentional shaping, monetary reinforcement only, or repeated practice. Participants in the attentional-shaping intervention showed improvements in face emotion identification over time at post-test and at 1-week follow-up. In addition, the shaping condition showed significantly higher scores than the monetary reinforcement group and the repeated practice group, with all three groups being roughly equivalent at pretest. The authors pointed out a nonsignificant trend for improved social functioning at follow-up and speculated that a one-time treatment may not realistically lead to a generalized effect on social functioning.

Another single-session method focusing on affect perception is a computer-based program known as the microexpression training tool (METT) [55]. In an initial study by Russell et al. [55], participants showed significant improvement on post-treatment scores measuring emotion recognition but did not significantly differ from healthy controls. In a new study by Russell et al. [56], the authors attempted to extend their original findings by investigating changes in attention associated with METT using eye movement recordings and adding an active control group to the study chosen through randomization. The authors found that the METT group directed significantly more eye movements within key areas of facial images such as the eyes, nose, and mouth compared with the control condition.

The training of affect recognition (TAR) intervention developed by Wolwer et al. [57] is an extended training program aimed at enhancing the ability to decode facial affect for people with schizophrenia. Analyses from three previous clinical trials of TAR showed improvements in facial affect recognition as compared with controls that were maintained for at least 8 weeks after treatment [57]. In a recent investigation, Frommann [58] compared TAR with cognitive remediation training using a pre– and post–control group design. Results indicated improvements in facial affect recognition as well as theory-of-mind performance. Further inquiry into the durability of training effects and the relationship of these effects to overall social and community functioning is needed.

Social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) addresses several social cognitive domains for people with schizophrenia [49••]. Penn et al. [59] developed this 20-week group intervention that targets emotion perception, attributional bias, and theory of mind. The three phases of the intervention are defining and identifying basic emotions through computerized exercises, modifying attributional styles related to interpersonal interactions, and attempting to generalize these skills through a series of interactive training exercises [16••]. Roberts and Penn [60] recently conducted a quasi-experimental study examining the SCIT intervention compared with treatment as usual for 31 outpatients with schizophrenia. Participants receiving the intervention significantly improved in emotion perception relative to the treatment-as-usual control group, a finding that replicates the outcomes of previous studies [61]. Participants also improved on some aspects of theory of mind, such as those relating to the detection of sarcasm, which may suggest the generalizability of the intervention, as this domain is not specifically targeted by the intervention. This notion was further supported by results demonstrating that SCIT was associated with improvements in social skills.

Combs et al. [62•] conducted a 6-month follow-up of participants who received SCIT on an inpatient basis in an earlier investigation [61]. In the original investigation, participants receiving SCIT showed significant improvement in emotion perception and social functioning compared with inpatients receiving a coping skills intervention, who did not improve on any outcomes. Results from the 6-month follow-up, which included all 18 original participants, indicated that improvement was maintained from baseline but declined from post-test. Importantly, the data suggest that SCIT participants demonstrated social cognitive performance on par with healthy controls at follow-up. One potential confound is that practice effects were based on repeated measures for the SCIT group, whereas the nonclinical control group was tested one time.

Roberts et al. [63••] also conducted an uncontrolled pre- and poststudy of SCIT to examine its feasibility in community settings. Results from multiple sources suggest that clinicians as well as clients perceived SCIT positively and rated it as “very helpful.” Attendance rates of about 69% along with favorable feedback from clients regarding SCIT were findings consistent with those of previous studies [59]. In addition, the authors noted that consistently high ratings from clinicians were particularly meaningful in light of previous findings that clinical staff may respond negatively to manualized and structured interventions [64]. Importantly, the authors found that administrators have adopted SCIT into routine services at several sites. Data collected also indicate significant improvements among participants in emotion perception, theory-of-mind performance, and attributional bias at post-treatment. In a related investigation, Turner-Brown et al. [65] tested the feasibility of SCIT for adults with autism in a quasi-experimental pilot study. The investigators also found that feasibility was supported by a high attendance rate (92%) and positive feedback from participants. Although data from this study are also preliminary, participants showed significant improvement in theory-of-mind skills and trend-level improvements in social skills compared with a treatment-as-usual control group.

Lastly, Horan et al. [66•] conducted a randomized controlled trial of a social cognitive skills training group for community-dwelling outpatients with schizophrenia. Thirty-four participants were randomly assigned to a social cognition group or an active control group receiving illness self-management skills. The intervention under study consists of two phases: 1) identifying basic emotions and understanding how emotions impact thoughts and behaviors in social contexts through didactic presentations and computerized facial affect recognition exercises and 2) understanding how symptoms such as paranoia shape beliefs about others’ intentions based on didactic presentations and vignettes aimed at awareness of social context and norms. Those who received social cognitive training showed significant improvement in facial affect perception, a finding that was not demonstrated in the active control condition. Feasibility data, based on an 83% mean attendance rate and feedback that the training was engaging and helpful to participants, demonstrated the relevance and transportability of the intervention for community-dwelling individuals with schizophrenia. This study highlights effective social cognitive training with clinically stable individuals living in the community as opposed to an inpatient population. However, the lack of changes in theory-of-mind performance and attributional style, both targets of the intervention, points toward the need for a further understanding of these complex domains. A large body of evidence now exists with regard to facial affect perception; however, theory of mind and attributional style are less well-understood in schizophrenia [16••]. It may be that exercises developed to tap these domains require further refinement, or that treatment dosing effects have not been adequately understood. Furthermore, it remains to be determined whether social cognitive training interventions function optimally when implemented in a standalone fashion or are more efficacious when integrated with basic neurocognitive remediation approaches.

Motivational Aspects of Rehabilitation

Complicating the picture of how to target neurocognitive and social cognitive interventions to improve functional outcomes is the role of motivation and how this may influence or be influenced by neurocognition and social cognition, as well as possibly by symptoms or illness. Given that the negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia include amotivation and apathy and that this in turn can influence a range of behaviors, such as failure to engage in work, relationships, or treatment [67], Barch et al. [68•] found an incongruence between self-reports of intrinsic motivation (IM) and cognitive functioning. They also found that IM was not related to negative symptoms, and that even in individuals with schizophrenia who reported high levels of IM, their cognitive impairments preclude this motivation from aiding them in laboratory-based cognitive tasks. Although external motivation has been studied less, there do appear to be differences in how to distinguish between external and internal motivation, but it is reasonable to conceptualize that both play an important role in the lives of individuals dealing with serious and persistent mental illness [69].

Several recent studies have found that IM mediates the relationship between neurocognition, social cognition, and functional outcomes [70••, 71••]. IM was also found to mediate the relationships between symptoms (positive, negative, disorganized) and psychosocial functioning [72•]. Given these findings, it can be expected that motivation will soon be the central focus of interventions, as it has been proposed that targeting motivation may be necessary to maximize cognitive remediation [67].

Integrated Interventions and Their Impact on Rehabilitation Outcomes

Another important trend in this field is the integration of specific treatments and adjunctive components—such as skills training and cognitive remediation—to help maximize the benefits of the vocational rehabilitation process. Cognitive remediation in conjunction with vocational rehabilitation has proven to enhance performance on measures such as attention and working memory, along with employment outcomes compared with those who receive vocational interventions alone [73, 74]. McGurk et al. [35••] recently conducted a randomized controlled trial to investigate the impact of adding cognitive remediation to a vocational rehabilitation program (supported employment/internship) compared with vocational rehabilitation alone. The authors found that consumers in the combination condition showed significant improvements on verbal learning, memory, and executive functioning (effect size range, 0.28–0.59), as well as hours worked and wages earned compared with those receiving vocational rehabilitation alone. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating the superiority of work outcomes for consumers who participate in combined cognitive and vocational rehabilitation programs compared with vocational programs alone [33, 73, 75]. Importantly, this study replicates the use of COGPACK software as an effective remediation package for consumers with schizophrenia [33, 75], helping to establish the utility of this tool with this population. Based on the finding that effect sizes of cognitive remediation were stronger for work than for cognitive performance, the authors concluded that the combination of compensatory strategies along with cognitive-enhancing skills was particularly effective in improving work outcomes. The study also raises questions regarding the interaction between specific cognitive training methods and vocational rehabilitation methods, such as what role motivation may play in mediating cognitive and vocational rehabilitation.

Bell et al. [76••] also recently conducted a randomized clinical trial of neurocognitive enhancement therapy combined with vocational rehabilitation (supported employment) compared with an active control group receiving vocational rehabilitation only. Participants receiving neurocognitive enhancement therapy in addition to the vocational program demonstrated more hours worked and higher rates of competitive employment than those receiving vocational rehabilitation alone. It is noteworthy that this study addresses several methodologic concerns raised in previous investigations, such as very high intensity treatment (up to 10 h/wk of computerized exercises + 2 groups/wk) and the durability of treatment effects based on 100% follow-up at 2 years.

Aside from cognitive remediation, investigators have examined other hybrid approaches to vocational rehabilitation for individuals with severe mental illness. Tsang et al. [77] examined the effectiveness of an integrated supported employment program that incorporates social skills training. A total of 163 participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: IPS alone, IPS combined with social skills, and traditional vocational rehabilitation. Participants in the combined condition demonstrated significantly higher employment rates (∼ 79%) than the active control condition and also had significantly longer job tenure (∼24 weeks). Social competence and problem-solving skills were enhanced through targeted training modules that were then generalized throughout follow-up sessions in the combined approach. Despite positive findings, the average tenure of participants in the combined approach represented 40% of the study duration (24 of 65 weeks). Therefore, determinants other than social competence that affect job tenure are an area requiring further study.

In a related investigation, Kern et al. [78••] evaluated the impact of errorless learning on work performance, tenure, and well-being as compared with a conventional job training program for community-dwelling outpatients with schizophrenia. A total of 40 participants were randomly assigned to an errorless learning condition versus conventional instruction while receiving job training. Results indicated that the errorless learning approach was superior to conventional instruction in relationship to work performance but did not significantly impact job tenure or job-related well-being. The authors noted that high baseline scores on self-esteem and low scores on work stress may have produced a ceiling effect that may obscure the true relationship of the experimental condition to these variables. Lastly, Major et al. [79] examined supported employment with an emphasis on education. The study was based on a naturalistic prospective cohort of 114 participants with first-episode psychosis who were observed for 12 months. Results indicate that supported employment in combination with education is a significant predictor of vocational recovery within 12 months. Although these preliminary results are promising, conclusions regarding the specificity of the treatment effect cannot be drawn due to the lack of methodologic rigor in the study.

Several recent studies have assessed the implementation of supported employment services across multiple sites and social contexts. Corbiere et al. [80] evaluated the fidelity of 23 supported employment programs in three Canadian provinces. Cluster analyses revealed six program profiles ranging from high fidelity with a rapid job search to low fidelity with family involvement. Five of the six profiles represented a high to moderate level of fidelity, and one profile had a low level of fidelity. Basic features of the program, such as pursuing competitive employment and conducting an individualized job search, were moderately to fully represented in almost all clusters. However, integration with other mental health services was fully implemented in only one cluster, highlighting an important gap in implementation, as research has shown that integration of vocational and clinical services is superior to nonintegrated services [6]. In examining current evidence regarding vocational rehabilitation, it is apparent that significant and far-reaching barriers to employment for people with severe mental illness remain a challenge to the field. Of those who have access to vocational interventions, only about one third are successful in obtaining competitive work, with even fewer maintaining significant job tenure [10••].

Conclusions

Growing evidence points to the effectiveness of certain social and vocational interventions for individuals with schizophrenia. An ongoing challenge is determining how to increase the effectiveness of these interventions in terms of the magnitude of their impact on individuals and how well they target critical areas of functioning in the community. Recent advances have been made in knowledge with regard to how neurocognition and social cognition influence functional outcomes. New interventions for improving neurocognition and social cognition in schizophrenia are also now available. These two factors have led to the integration of interventions for improving social and vocational outcomes with interventions that target improvements in neurocognition and social cognition. These new integrated interventions hold promise for improving the social and vocational outcomes for individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

• Bellack AS, Green MF, Cook JA, et al.: Assessment of community functioning in people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses: a white paper based on an NIMH-sponsored workshop. Schizophr Bull 2007, 33:805–822. The article reports recent progress in developing interventions targeting impairments in community functioning for people with schizophrenia. The National Institute of Mental Health convened a workgroup to address inconsistencies in measuring functional outcomes, and the authors provide recommendations regarding standard assessment in this area.

Pratt SI, Van Citters AD, Mueser KT, Bartels SJ: Psychosocial rehabilitation in older adults with serious mental illness: a review of the research literature and recommendations for development of rehabilitative approaches. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 2008, 11:7–40.

• Kern RS, Glynn SM, Horan WP, Marder SR: Psychosocial treatments to promote functional recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2009, 35:347–361. In this recently published review, the authors critically examine a wide range of interventions that promote functional recovery in schizophrenia. They also provide an evaluation of the interaction between pharmacologic and psychosocial treatments in relationship to functional recovery in schizophrenia.

Bond GR, Campbell K: Evidence-based practices for individuals with severe mental illness. J Rehabil 2008, 74:33–43.

Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al.: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Serv 2001, 52:313–322.

Cook JA, Lehman AF, Drake R, et al.: Integration of psychiatric and vocational services: a multisite randomized, controlled trial of supported employment. Am J Psychiatry 2005, 162:1948–1956.

Killackey E, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD: Vocational intervention in first-episode psychosis: individual placement and support v. treatment as usual. Br J Psychiatry 2008, 193:114–120.

Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, et al.: The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry 2005, 66:1122–1129.

Leff J, Warner R: Social Inclusion of People With Mental Illness. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

•• Drake RE, Bond GR: The future of supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2008, 31:367–376. This review examines current research on the effectiveness of supported employment and efforts aimed at the dissemination of the intervention. Key areas for future research that are discussed include financing of services, motivation, and illness-related barriers to improving vocational outcomes.

Shean GD: Evidence-based psychosocial practices in recovery from schizophrenia. Psychiatry 2009, 72:307–320.

Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR: An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2008, 31:280–290.

Twamley EW, Narvaez JM, Becker DR, et al.: Supported employment for middle-aged and older people with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 2008, 11:76–89.

Becker DR, Drake RE: Individual placement and support: a community mental health center approach to vocational rehabilitation. Community Ment Health J 1994, 30:193–206.

•• Burns T, Catty J, White S, et al.: The impact of supported employment and working on clinical and social functioning: results of an international study of individual placement and support. Schizophr Bull 2009, 35:949–958. This multinational study found that people with severe mental illness receiving IPS had better global functioning than those receiving general vocational rehabilitation at 18-month follow-up. Importantly, the authors found that IPS was better than the control condition at improving the outcomes of more severely impaired participants.

•• Horan WP, Kern RS, Green MF, Penn DL: Social cognition training for individuals with schizophrenia: emerging evidence. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 2008, 11:205–252. In this recent review, the authors critically examine studies investigating the modifiability of social cognition in schizophrenia. Evidence pertaining to brief social cognitive manipulations and longer-term social cognitive training suggests that certain treatments enhance functioning across multiple domains of social cognition.

Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al.: Skills training versus psychosocial occupational therapy for persons with persistent schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1998, 155:1087–1091.

Benton MK, Schroeder HE: Social skills training with schizophrenics: a meta-analytic evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990, 58:741–747.

Mueser KT, Penn DL: Meta-analysis examining the effects of social skills training on schizophrenia. Psychol Med 2002, 32:783–793.

Evans JD, Bond GR, Meyer PS, et al.: Cognitive and clinical predictors of success in vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2004, 70:331–342.

Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, et al.: A randomized, controlled trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for middle-aged and older outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2005, 162:520–529.

Kurtz MM, Mueser KT: A meta-analysis of controlled research on social skills training for schizophrenia. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008, 76:491–504.

Wykes T, Katz R, Sturt E, Hemsley D: Abnormalities of response processing in a chronic psychiatric group: a possible predictor of failure in rehabilitation programs. Br J Psychiatry 1992, 160:244–252.

•• Medalia A, Choi J: Cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Neuropsychol Rev 2009, 19:353–364. This recent review examines differing approaches to cognitive remediation and provides important insight into the heterogeneity of responses to cognitive remediation. Factors such as varying instructional techniques, motivational factors, and ability level are discussed with regard to differential outcomes.

• Brekke JS, Nakagami E: The relevance of neurocognition and social cognition for outcome and recovery in schizophrenia. In Neurocognition and Social Cognition in Schizophrenia Patients. Basic Concepts and Treatment. Edited by Roder V, Medalia A. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 2010:23–36. This chapter critically evaluates the most recent research on neurocognition and social cognition with an emphasis on their relevance to functional outcome in schizophrenia. Studies investigating how these domains may serve as predictors, mediators, and moderators of functioning are explored.

Brekke JS, Kay DD, Lee KS, Green MF: Biosocial pathways to functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2005, 80:213–225.

Wykes T, Huddy V: Cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: it is even more complicated. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2009, 22:161–167.

Brekke JS, Hoe M, Long J, Green MF: How neurocognition and social cognition influence functional change during community-based psychosocial rehabilitation for individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2007, 33:1247–1256.

•• Brekke JS, Hoe M, Green MF: Neurocognitive change, functional change and service intensity during community-based psychosocial rehabilitation for schizophrenia. Psychol Med 2009, 39:1637–1647. This study examined the magnitude of neurocognitive change, whether neurocognitive change and functional change were interrelated, and how service intensity affected these domains for individuals with schizophrenia receiving psychosocial rehabilitation during a 1-year period. The authors found that neurocognitive improvers demonstrated functional improvement that was 350% greater than neurocognitive nonimprovers. In addition, there was a strong interaction between neurocognitive improvement, service intensity, and rate of functional improvement.

Woodruff-Pak D: Neural Plasticity as a Substrate for Cognitive Adaptation in Adulthood and Aging. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1993.

Velligan DI, Bow-Thomas CC: Two case studies of cognitive adaptation training for outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2000, 51:25–29.

McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, et al.: A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2007, 164:1791–1802.

Lindenmayer JP, McGurk SR, Mueser KT, et al.: A randomized controlled trial of cognitive remediation among inpatients with persistent mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2008, 59:241–247.

• Szoke A, Trandafir A, Dupont ME, et al.: Longitudinal studies of cognition in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2008, 192:257–266. This recent meta-analysis of longitudinal studies examining cognitive remediation in schizophrenia based on 2476 people demonstrated that participants improved in most cognitive domains, including memory, cognitive flexibility, and vigilance and attention.

•• McGurk SR, Mueser KT, DeRosa TJ, Wolfe R: Work, recovery, and comorbidity in schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial of cognitive remediation. Schizophr Bull 2009, 35:319–335. This study examined a hybrid treatment approach integrating cognitive remediation and vocational rehabilitation compared with vocational rehabilitation alone for people with schizophrenia. The hybrid approach showed superior work outcomes, and these gains demonstrated significant durability based on a 2-year follow-up period.

•• Lecardeur L, Stip E, Giguere M, et al.: Effects of cognitive remediation therapies on psychotic symptoms and cognitive complaints in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a randomized study. Schizophr Res 2009, 111:153–158. In this study, two cognitive remediation therapy approaches were compared for individuals with schizophrenia, one targeting mental state attribution and the other targeting mental flexibility. Results suggested greater improvement in the mental flexibility group, a finding that helps shed light on the differential impact of cognitive remediation techniques.

McGurk SR, Mueser KT: Response to cognitive rehabilitation in older versus younger persons with severe mental illness. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 2008, 11:90–105.

Medalia A, Richardson R: What predicts a good response to cognitive remediation interventions? Schizophr Bull 2005, 31:942–953.

Silverstein SM, Spaulding WD, Menditto AA, et al.: Attention shaping: a reward-based learning method to enhance skills training outcomes in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2009, 35:222–232.

Fisher M, Holland C, Merzenich MM, Vinogradov S: Using neuroplasticity-based auditory training to improve verbal memory in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2009, 166:805–811.

Cavallaro R, Anselmetti S, Poletti S, et al.: Computer-aided neurocognitive remediation as an enhancing strategy for schizophrenia rehabilitation. Psychiatry Res 2009, 169:191–196.

Velligan DI, Diamond PM, Mintz J, et al.: The use of individually tailored environmental supports to improve medication adherence and outcomes in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2008, 34:483–493.

•• Penn DL, Sanna LJ, Roberts DL: Social cognition in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull 2008, 34:408–411. This recent review synthesizes current research on the key domains of social cognition, including emotion perception, theory of mind, and attributional style. Findings from these studies are examined within the context of the relationship between social cognition and neurocognition, negative symptoms, and functional outcomes.

Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR, Sitarenios G: Emotional intelligence as a standard of intelligence. Emotion 2001, 1:232–242.

Kee KS, Horan WP, Wynn JK, et al.: An analysis of categorical perception of facial emotion in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2006, 87:228–237.

Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C: Theory of mind impairment in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 2009, 109:1–9.

Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL: The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull 2006, 32:S44–S63.

Green MF, Olivier B, Crawley JN, et al.: Social cognition in schizophrenia: recommendations from the MATRICS new approaches conference. Schizophr Bull 2005, 31:882–887.

•• Wolwer W, Combs DR, Frommann N, Penn DL: Treatment approaches with a special focus on social cognition: overview and empirical results. In Neurocognition and Social Cognition in Schizophrenia Patients. Basic Concepts and Treatment. Edited by Roder V, Medalia A. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 2010:61–78. This chapter summarizes the most current research on specialized treatment approaches targeting social cognition in schizophrenia. The authors evaluate narrow treatment approaches focusing on a single domain of social cognition, as well as broad-based strategies targeting multiple domains.

Roncone R, Mazza M, Frangou I, et al.: Rehabilitation of theory of mind deficit in schizophrenia: a pilot study of metacognitive strategies in group treatment. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2004, 14:421–435.

Moritz S, Woodward TS: Metacognitive training for schizophrenia patients (MCT): a pilot study on feasibility, treatment adherence, and subjective efficacy. Ger J Psychiatry 2007, 10:69–78.

Penn DL, Combs D: Modification of affect perception deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2000, 46:217–229.

Addington J, Addington D: Facial affect recognition and information processing in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res 1998, 32:171–181.

• Combs DR, Tosheva A, Penn DL, et al.: Attentional-shaping as a means to improve emotion perception deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2008, 105:68–77. This study represents a novel intervention using attentional-shaping procedures to draw attention to the center of the face in order to improve emotion perception for individuals with schizophrenia. The attentional-shaping condition showed significantly higher scores on the Face Emotion Identification Test than monetary reinforcement and repeated practice control groups.

Russell TA, Chu E, Phillips ML: A pilot study to investigate the effectiveness of emotion recognition remediation in schizophrenia using the micro-expression training tool. Br J Clin Psychol 2006, 45:579–583.

Russell TA, Green MJ, Simpson I, Coltheart M: Remediation of facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: concomitant changes in visual attention. Schizophr Res 2008, 103:248–256.

Wolwer W, Frommann N, Halfmann S, et al.: Remediation of impairments in facial affect recognition in schizophrenia: efficacy and specificity of a new training program. Schizophr Res 2005, 80:295–303.

Frommann N, Fleiter J, Peltzer M, et al.: Training of affect recognition (TAR) in schizophrenia: generalizability and durability of training effects. Schizophr Res 2008, 98:55.

Penn DL, Roberts DL, Combs D, Sterne A: Best practices: the development of the social cognition and interaction program for schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Serv 2007, 58:449–451.

Roberts DL, Penn DL: Social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) for outpatients with schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Psychiatry Res 2009, 166:141–147.

Combs DR, Adams SD, Penn DL, et al.: Social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) for patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: preliminary findings. Schizophr Res 2007, 91:112–116.

• Combs DR, Penn DL, Tiegreen JA, et al.: Stability and generalization of social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) for schizophrenia: six-month follow-up results. Schizophr Res 2009, 112:196–197. This follow-up study examining SCIT for schizophrenia provides important information regarding the durability of social cognitive treatment approaches. Although the authors found that initial improvement had declined from post-test, SCIT participants demonstrated social cognitive performance on par with that of healthy controls at 6-month follow-up.

•• Roberts DL, Penn DL, Labate D: Transportability and feasibility of social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) in community settings. Behav Cogn Psychother 2010, 38:35–47. This study investigating SCIT in community settings provides evidence regarding the transportability of the approach in a real world setting. Results indicate significant improvements in social cognitive domains and favorable feedback from participants and clinicians with respect to feasibility in community-based agencies.

Addis ME, Krasnow AD: A national survey of practicing psychologists’ attitudes toward psychotherapy treatment manuals. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000, 68:331–339.

Turner-Brown LM, Perry TD, Dichter GS, et al.: Brief report: feasibility of social cognition and interaction training for adults with high functioning autism. J Autism Dev Disord 2008, 38:1777–1784.

• Horan WP, Kern RS, Shokat-Fadai K, et al.: Social cognitive skills training in schizophrenia: an initial efficacy study of stabilized outpatients. Schizophr Res 2009, 107:47–54. This randomized controlled trial of a social cognitive skills training group for individuals with schizophrenia living in the community highlights evidence for this approach based on a clinically stable population as opposed to an inpatient population. Participants showed significant improvement in facial affect perception and an 83% mean attendance rate.

Velligan DI, Kern RS, Gold, JM: Cognitive rehabilitation for schizophrenia and the putative role of motivation and expectancies. Schizophr Bull 2006, 32:474–485.

• Barch DM, Yodkovik N, Sypher-Locke, et al.: Intrinsic motivation in schizophrenia: relationships to cognitive function, depression, anxiety, and personality. J Abnorm Psychol 2008, 117:776–787. This study provides important insight into the relationship between self-reports of IM and measures of cognitive functioning and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Importantly, the authors found an incongruence between self-reports of IM and cognitive function.

Silverstein SM: Bridging the gap between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the cognitive remediation of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2010 Jan 11 (Epub ahead of print).

•• Nakagami E, Xie B, Hoe M, Brekke JS: Intrinsic motivation, neurocognition and psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia: testing mediator and moderator effects. Schizophr Res 2008, 105:95–104. This investigation reveals the influence of neurocognition on psychosocial functioning through its relationship with IM. These findings highlight the need for interventions targeting IM.

•• Gard DE, Fisher M, Garrett C, et al.: Motivation and its relationship to neurocognition, social cognition, and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2009, 115:74–81. This study examines the role of motivation in relationship to social cognition, an area that few studies have investigated. Results suggest that motivation mediates the relationship between neurocognition, social cognition, and functional outcome.

• Yamada AM, Lee KK, Dinh TQ, et al.: Intrinsic motivation as a mediator of relationships between symptoms and functioning among individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in a diverse urban community. J Nerv Ment Dis 2010, 198:28–34. This study found that IM mediates the relationship between clinical symptoms and functioning. Few studies have examined ethnic minority differences with regard to motivation, and results from this study indicate that motivation scores between ethnic minority individuals with schizophrenia and nonminority individuals differed significantly, although no moderation effect was found.

Vauth R, Corrigan PW, Clauss M, et al.: Cognitive strategies versus self-management skills as adjunct to vocational rehabilitation. Schizophr Bull 2005, 31:55–66.

Wexler BE, Bell MD: Cognitive remediation and vocational rehabilitation for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2005, 31:931–941.

McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Pascaris A: Cognitive training and supported employment for persons with severe mental illness: one year results from a randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Bull 2005, 31:898–909.

•• Bell MD, Zito W, Grieg T, Wexler BE: Neurocognitive enhancement therapy with vocational services: work outcomes at two-year follow-up. Schizophr Res 2008, 105:18–29. This randomized controlled trial of neurocognitive enhancement therapy is noteworthy in that the study addresses several methodologic concerns raised in previous studies by providing high-intensity treatment and measuring the durability of treatment effects based on a 100% follow-up after 2 years.

Tsang HW, Chan A, Wong A, Liberman RP: Vocational outcomes of an integrated supported employment program for individuals with persistent and severe mental illness. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2009, 40:292–305.

•• Kern RS, Liberman RP, Becker DR, et al.: Errorless learning for training individuals with schizophrenia at a community mental health setting providing work experience. Schizophr Bull 2009, 35:807–815. This study represents a novel approach to integrating errorless learning with conventional job training in a community setting for individuals with schizophrenia. Results indicate modest support for the superiority of the hybrid approach as opposed to conventional job training in enhancing work performance.

Major BS, Hinton MF, Flint A, et al.: Evidence of the effectiveness of a specialist vocational intervention following first episode psychosis: a naturalistic prospective cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010, 45:1–8.

Corbiere M, Lanctot N, Lecomte T, et al.: A pan-Canadian evaluation of supported employment programs dedicated to people with severe mental disorders. Community Ment Health J 2010, 46:44–55.

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kurzban, S., Davis, L. & Brekke, J.S. Vocational, Social, and Cognitive Rehabilitation for Individuals Diagnosed With Schizophrenia: A Review of Recent Research and Trends. Curr Psychiatry Rep 12, 345–355 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-010-0129-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-010-0129-3