Abstract

Purpose of Review

The aim of the review is to conduct a literature search on cost-effectiveness or cost savings of osteoporosis fracture liaison services.

Recent Findings

We identified four types of FLS. A total of 11 cost-effectiveness studies examining 15 models of secondary fracture prevention models were identified. Nine models were found to be cost-saving, and five were found to be cost-effective.

Summary

It is possible to adopt a cost-effective model for fracture liaison services and expand across geographical regions. Adopting registries can have the added benefit of monitoring quality improvement practices and treatment outcomes. Challenges exist in implementing registries where centralized data collections across different chronic conditions are politically driving agendas. In order to align political and organizational strategic plans, a core set of outcome evaluations that are both focused on patient and provider experience in addition to treatment outcomes can be a step toward achieving better health and services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Trauma registries are recognized as providing useful information about acute care delivered to patients hospitalized with injuries. A patient registry is defined as “an organized system that uses observational study methods to collect uniform data (clinical and other) to evaluate specified outcomes for a population defined by a particular disease, condition, or exposure and that serves one or more predetermined scientific, clinical, or policy purposes.” Registries are surveillance systems that capture data that can help to improve quality of services and simultaneously allow the patient and caregiver to make informed decisions independently from the intended purpose of the registry. Indeed we have noted, in a national evaluation of a trauma registry, that mortality rates have diminished [1]. There are also implications when trauma centers vs. non trauma centers have demonstrated better results for those patients presenting with more severe injuries rather than those with less severe injuries. In these cases, prioritizing patient flow, for those with less severe injuries, and allowing these patients to receive care either at home or in the community and/or discharged from the hospital earlier can improve the quality of services throughout the patient’s care. These gaps in the continuum of care need to be addressed and carefully monitored through the development and use of registries or a data centralized system of integrated care. Considerable financial investments and political drive in addition to consistent data definitions and specialized personnel, like clinical epidemiologists, are fundamental factors in determining service efficiencies and prevention of fracture [2]. Our objective with this review of the current literature is to examine the cost-effectiveness of orthogeriatric and fracture liaison service models for patients presenting with hip fracture. We will present recommendations to inform the development of a hip fracture registry to reduce the incidence of hip and other fragility fractures. Our review will capture relevant outcomes, underpinning the Quadruple Aim and conceptual frameworks, including information on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Aligning Political Agendas with Organizational Structures and Hospital Strategic Plans to Evaluate the Economic Impact of Hip Fractures

Cross country data comparisons for the reduction of hip fracture and mortality rates can only occur if the program design is transparent and co-designed with representatives of every stakeholder group that will be involved in the program, including patients. Programs should align with organizations’ strategic planning timelines and timelines for related initiatives, such as quality improvement plans [3]. The applicability and feasibility of measurement should be considered for each organization expected to participate. Further, benchmarking may be attributed at least in part to the implementation of a registry and support networks that provide a dashboard to contributing sites. The chance to improve the management of data can assist individual hospitals to adapt to their capacity, size, and resources [4]. Understanding the impact that certain policy drivers [5] can have for buy-in from each of the individual hospitals is dependent on having a live report of risk-adjusted outcomes in a cross comparison with other similar sites.

Establishing a mix of mandatory outcomes and a selection of optional outcomes can help to balance government priorities with the needs of patients with hip fracture and those needs stipulated in organizational strategic plans. To understand the relevance of registries that are driven by governments, we can find a plethora of resources in the grey literature across different jurisdictions. Other nationally driven initiatives are learning from Sweden [6] and the UK [7] who have created a rich network of registries. Australia has 28 clinical registries, almost rivaling Sweden’s 70 registries, which have established outcomes that address both population outcomes and health system processes to measure quality improvements. Missing variables and time lag, especially for outcomes linked to patient self-report, can impose significant hurdles. Patients and their caregivers must be contacted by staff personnel, and should the patients not be available questionnaire responses may not be entered into the database. We can learn valuable lessons reviewing the resources for guiding the design, implementation, and data evaluation of these registries [8]. In Australia, “Operating principles and technical standards for Australian clinical quality registries” were developed under the auspices of the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, and the processes are currently undergoing validation [9, 10].

Osteoporosis can lead to secondary fractures leaving the elderly in critical conditions unless they are managed appropriately. Although wrist injuries are sentinel fractures in determining the diagnosis for osteoporosis, the incidence of hip fractures can be more costly. Alleviating the strain on hospital resources is imperative, especially as these rates are noted to rise among patients with complex comorbidities. However, gathering relevant information on hip fractures can be a challenge. Hip fracture outcomes are captured by arthroplasty registries in some European countries [11,12,13], while other countries have dedicated hip fracture registries: Australia [14], New Zealand [15], Canada [16], Norway [17], Sweden [18], and the United Kingston [19]. Good quality registry data can be a challenge, whereby missing information and data sources indicate discontinued continuums of care across various geographical regions and community services to help patients presenting with hip fracture. There seems to be a growing momentum to develop hip fracture registries across integrated health care systems, like Kaiser Permanente [20]. The registry holds information on demographics, interventions, morbidity, and mortality as well as characteristics of both the surgeon and the hospital. Most of the information gathered by the registries still have room for improvement, and we suggest mapping outcomes onto conceptual frameworks and the Quadruple Aim, which includes elements related to the work environment where the providers may experience stress or burnout, in order to get a more comprehensive picture of the patient journey through care.

Using the OMERACT Conceptual Framework to Map a Core Set of Outcomes

The framework that embeds both a population and system level was developed by Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) in 2014 [21]. In collaboration with the AO foundation, in 2011, the expert panelists developed a core set of outcomes for the orthogeriatric co-management of hip fracture. A paper was published as a result of these discussions by Liem et al. [22•], who present a core set of outcome parameters to assess best treatment practices for the management of hip fractures in an interprofessional environment, which we mapped onto the OMERACT framework (Table 1).

Outcomes need to be collected in a reliable way such that there is a better buy in from the hospitals and then incorporated into organizational strategic plans. The panelists contributing to the development of the core set determined that the collection of 12 parameters should be set upon admission, discharge, 30-day-, 90-day, and at 1 year following admission of the patient presenting with hip fracture. Three countries (US, UK, and the Netherlands) have published reports stating that 40–44% of the population in the studies recovered their pre-fracture mobility independence at 1 year [23]. Policy makers who rely on performance indicators will need to choose outcomes that can demonstrate improvement over shorter time frames. Collecting outcomes measuring mobility in this patient population at one-year follow-up given the relatively healthy patient does not provide information about what occurred prior to the 1-year mark. If mobility does not demonstrate change at 30 days, this domain may not be important even as a political driver despite the fact that it may be relevant to the patient. Short- and long-term outcomes are necessary to get a comprehensive picture of what happens following a hip fracture. Setting appropriate time frames should be linked to clinical hospital capacity such that acute care hospitals have different needs affecting the choice of appropriate outcome measures.

Results from a systematic review were recently published and showed similar core domains although no consensus methodology was reported. It is ideal to report domains in each of the core areas such as the one we adopted that highlight all aspects of measurement. Dyer at al [23]. used the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [24]; however, the authors also note the importance of additional domains (such as accommodation, quality of life and mortality, and health condition) that do not sit within this framework but would fit within the OMERACT framework.

The hip fracture outcome group identified patient reported experience as an important domain to assess but did not have any identified instrument to assess this. Interestingly, we can learn from an initiative funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Ministry of Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) that incorporated patient experience in a pilot to link funding to quality. In 2015, the Hospital Advisory Committee (HAC) was organized as a governance structure that was part of the Health System Funding Reform (HSFR); it was designed to provide the then Ontario MOHLTC with advice and recommendations to improve and evolve HSFR in terms of efficiency, access and equity, safety, and patient-centered care. HAC identified linking quality to funding (LQ2F) as a priority area within HSFR.

In 2018, the MOHLTC in conjunction with the Ontario Hospital Association announced the launch of the LQ2F pilot. Table 2 reports the 5 indicators chosen in the domains of patient experience, safety, and effectiveness. These domains were drawn from Health Quality Ontario’s 2019 report, “Quality Matters” [25].

We recommend that outcome sets need to consider whether there is alignment with government directives, whether the outcomes are feasible, i.e., can they be calculated using the existing data infrastructure, are hospitals familiar with the outcomes, and/or are the hospitals already collecting the outcomes and that the evaluation of performance and benchmarking is within the control of the hospital. Further, the outcomes selected need to be scientifically sound, such that the outcomes are valid and reliable, and the evidence behind the outcome is explicit.

Fracture Liaison Services

Ganda et al. [26•] described four models of fracture liaison services (FLS) with decreasing levels of intensity:

Type A: Type A models of care represent following protocol for secondary fracture prevention, where following a minimal trauma fracture, patients are identified, assessed, and treated.

Type B: Type B models of care stop short of treatment initiation, instead providing the primary care physician with recommendations based on the FLS assessment.

Type C: Type C models of care are less-intensive, in that individuals identified as suffering minimal trauma fractures are provided with osteoporosis education and advice, and their primary care physician is alerted of the fracture with recommendation for further assessment to reduce the risk for additional fractures.

Type D: Type D interventions include only education and advice to individuals presenting with a minimal trauma fracture. No physician contact is included in this model.

Wu et al. [27•] report that cost-effectiveness studies of secondary fracture prevention interventions were conducted in Canada, Australia, US, UK, Japan, Taiwan, and Sweden. In comparisons with usual care or no treatment, FLS of all intensity models were consistently cost-effective across countries (cost per quality and duration of life following medical or surgical treatment, as measured in QALY, ranges from USD $3023–28,800 [CAD $3779–36,000] in Japan to USD $14,513–112,877 [CAD $18,141–141,096] in the US, with several studies documented cost savings.

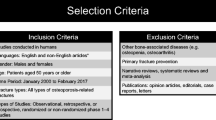

Methods

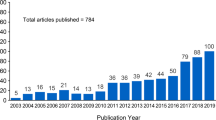

A search of the literature was conducted through PubMed and Google Scholar using the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms “accidental falls,” “cost-benefit analysis,” “hip fractures,” “osteoporosis,” and “osteoporotic fractures” in combination with the following keywords to identify relevant articles and documents: “cost,” “cost-effectiveness,” “fall prevention,” “FLS,” “fracture liaison service,” “intervention,” and “orthogeriatrics.”

Results

A total of 11 cost-effectiveness studies examining 15 models of secondary fracture prevention models (types A, B, and C, as well as an orthogeriatric model) were identified in the literature. Overall, nine models were found to be cost saving, and five were found to be cost-effective. While all three types of FLS were found to be cost-saving in some studies and cost-effective in others, cost savings tended to be smaller in the less intensive Type C FLS studies, and cost-effectiveness lower (i.e., higher cost per quality and duration of life following medical or surgical treatment), compared to the more intensive Type A FLS. Table 3 provides a list of study characteristics and models.

Discussion

Establishing a Rationale for a New Hip Fracture Registry

The UK’s model of a National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD, https://www.nhfd.co.uk last accessed January 1, 2020) is a leader in national efforts to establish a similar database in other countries, like Canada, that has existing parallels with the UK’s health care system. The NHFD data shows that the average length of acute stay decreased from 19.7 days in 2009 to 15.6 days in 2017 [42, 43]. An economic simulation using similar methodology for the province of Ontario in Canada suggests that province could save over 43,000 acute inpatient bed days per year across the province within the first few years of operation.

We would advise caution when interpreting these results should the rationale attribute all the UK’s decrease in average length of acute stay to the NHFD initiative since the NHFD reports do not substantiate a causal relationship. We could imagine several other factors (e.g., changes in general population health, increased overall health system efficiency, etc.) that can cause the decline in length of acute stay between 2009 and 2017 apart from the NHFD initiative, which was established in 2007. Furthermore, comparing two data points is not very convincing. Ideally, we would evaluate the UK data before the NHFD initiative began and data from a control group jurisdiction that never implemented a hip fracture database. According to the NHFD reports [42, 43], patient mortality was lower by about 7% in 2017, but it is not clear what the comparative time period is here; it may refer to a 7% decrease in the mortality rate from 2009 to 2017, as 2009 was the first year the NHFD report was published. Here again, causation cannot be inferred from the correlation – the fact that the mortality rate decreased by 7% over the course of the NHFD’s existence does not mean that the NHFD caused that decrease. Data on the trend in mortality rate from before the establishment of the NHFD could be helpful here.

Building a Rationale for Extending a Program Across the Province

Our findings are similar to those reported by Yong et al. [39] (2016), who found that the standard version of the Fracture Screening and Secondary Prevention Program (FSPP), a type C FLS, had an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of roughly CAD$20,000 per QALY compared with the more intensive Fast Track model (Type A), which had an ICER of CAD$5720 per QALY. Yong et al. [40] argue that extending the fracture screening and prevention program would be cost-effective, but it may emphasize that it is better to extend such a program across the province using the less intensive model. Additionally, Yong et al. were careful to note that the study of the Fast Track model was a secondary analysis because the sample size was much smaller (roughly n = 200) than the sample size in the main analysis. The Fast Track model has only been implemented at a large teaching hospital in Toronto, whereas the standard model is what has been implemented in 33 clinics across the province.

As a minor note, Yong et al. [39] also state that the Fast Track program was much more cost-effective in non-hip fracture patients than in hip fracture patients ($3213 vs. $51,377 per QALY gained). Yong et al. [39] report that their findings are “not generalizable to settings with low volume of fragility fracture patients (less than 300 per year), where a centralized model may be more appropriate.” Finally, the study has some methodological flaws: (1) the cost effectiveness results are very sensitive to parameter alterations, (2) the authors rely on many assumptions and simplifications, and (3) there may be substantial selection bias if eligible patients are not mandated to use the FSPP.

In the literature, we found cost savings findings specifically for hip fractures and warrants further investigation:

National joint registries for England and Wales include cost savings for specific interventions, i.e., the financial implications of uncemented versus cemented total hip replacements on a national scale [44].

Total hip arthroplasty is a cost-effective surgical procedure to alleviate pain so that the hip recovered functionality. These findings were verified using registries and noting the importance of implant survivorship was urged [45].

A strategic approach with economic impact based on raising the bar on current practices can come from registry data [46].

Selecting Outcomes for a Hip Fracture Registry

While orthogeriatric care protocols and liaison services remain simple in theory, the patient and their caregiver remain at the forefront of the decision-making. Patient-centered care is still empowering, and outcomes that address not only treatment outcomes but also patient experience should be incorporated into registries in order to set value to an otherwise mechanistic and labor/resource-intensive dialogue about gathering hip fracture data. In the 2017 annual report issued by the Swedish Registry Programme, the authors noted that there was the patient reported outcome measures (PROM) program in place to capture patient information for those intending on receiving elective surgery for hip arthroplasties [11]. Reminders are issued such that there is a lag in time to have the registrar updated with complete questionnaires.

Conclusions

Registries can be developed in design to align political, organizational drivers with clinical outcome results. For policy makers, Type C models of care that are less intensive seem most appropriate to expand. These current secondary fracture prevention strategies are easier to scale up in times of fiscal restraint. Type C models tend to showcase smaller cost savings and lower cost-effectiveness compared to the more intensive type A fracture liaison services. The use of patient outcomes based on specific interventions can enhance the dialogue generated from hip fracture or hip device registries. Current gaps exist in collecting the right data to capture patient and provider experience. Acute care hospitals are working to refine the process and identifying the right questions to ask patients about their care, while there is still no evidence around what questions need to be asked to understand provider experience, e.g., how well do providers access all necessary information from the patients digital health record or are there enough staff/resources on hand so they can discharge the patient in a timely manner. Developing registries is warranted, for both clinicians and policy makers, when its value outweighs the cost of collecting high quality data and the benefits, like decision-making, can be drawn from either the items or services in the registries.

Future Directions

Global challenges exist for countries to integrate protocols for hip fracture management into health care services, and governments struggle with finding the right combination of incentivized systems for patients to access the right care at the right time. Evidence from cost-effectiveness studies suggests that implementing fracture liaison services benefits patients as well as systems. Mandating screening and falls prevention remain a simple solution for ministries that seek short term results; however, funding digital health initiatives within primary, long-term, and community care can facilitate overcoming barriers in its uptake. On one hand, Ontario is presently battling dozens of electronic medical records vendors, which makes integrating health information difficult such that it is accessible across chronic conditions and hospital treatment centers. Additionally, the development of registries will challenge current provincial technology budgets and legislation dealing with linked personal health information, but the advantage of these monitoring systems can make poor hospital performers surface and serve as an incentive to treat and manage patients presenting with hip fracture according to standards [47].

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Frey KP, Egleston BL, et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006;354.4:366–78.

Moore L, Clark DE. The value of trauma registries. Injury. 2008;39.5:686–95.

McNeil JJ, Evans SM, Johnson NP, Cameron PA. Clinical-quality registries: their role in quality improvement. Med J Aust. 2010;192.5:244–5.

Health Quality Ontario: Rapid Access Clinics for Musculoskeletal Care. Website: https://www.hqontario.ca/Quality-Improvement/Quality-Improvement-in-Action/Rapid-Access-Clinics-for-Musculoskeletal-Care. Last accessed January 9, 2020.

Health Quality Ontario. Annual priorities for 2020/21 Quality improvement plans. Website: https://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/qi/qip/annual-memo-2020-2021-en.pdf. Last accessed: January 9, 2020.

eyenet Sweden. Handbook for establishing quality registries: Eye Net Sweden; 2005. (http://demo.web4u.nu/eyenet/uploads/Hanbooken%20engelsk%20version%20060306.pdf. Last accessed December 27, 2020)

Black N, Payne M. Directory of clinical databases: improving and promoting their use. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:348–52.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: a user’s guide. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006.

Evans SM, Bohensky M, Cameron PA, McNeil J. A survey of Australian clinical registries: can quality of care be measured? Intern Med J. 2009;41.1a:42–8.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Operating principles and technical standards for Australian clinical quality registries. 2008.

Karrholm J, Mohadden M, Odin D, Vinblad J, Rogmark C, Rolfson O. Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register annual report 2012. 2017. (https://registercentrum.blob.core.windows.net/shpr/r/Eng_Arsrapport_2017_Hoftprotes_final-Syx2fJPhMN.pdf last accessed March 29, 2020).

Stea S, Bordini B, De Clerico M, Petropulacos K, Toni A. First hip arthroplasty register in Italy: 55,000 cases and 7 year follow-up. Int Orthop. 2009;33(2):339–46.

Smith AJ, Dieppe P, Howard PW, Ashley W, Natl Joint Registry England Wales and National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Failure rates of metal-on-metal hip resurfacings: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Lancet. 2012;380.9855:1759–66.

Australian Orthopedic Association national joint replacement registry . Hip and knee arthroplasty: 2014 annual report. Adelaide, 2014. https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/documents/10180/172286/Annual+Report+2014. Last accessed: March 29, 2020.

New Zealand Orthopaedic Association. The New Zealand Joint Registry. Fourteen Year Report. Jannuary 1999 to December 2012. 2015. 28 December 2019. http://www.nzoa.org.nz/system/files/NJR%2014%20Year%20Report.pdf.

Canadian Joint Replacement Registry (2014) Annual report. Canadian Institute for Health Information Hip and Knee Replacements in Canada: Canadian Joint Replacement Registry 2014 Annual Report 2014 28 December 2019. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/CJRR%202014%20Annual%20Report_EN-web.pdf.

The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. N.d. 28 December 2019. http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/eng/#Publications: last accessed March 29, 2020..

Thorngren KG. In: Bentley G, editor. National registration of hip fractures in Sweden. New York: Springer & Science & Business Media; 2009.

Royal College of Physicians. Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit Programme (FFFAP) National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD) annual report 2014. London; 2014.

Inacio MCS, Weiss JM, Miric A, Hunt JJ, Zohman GL, Paxton EW. A community-based hip fracture registry: population, methods, and outcomes. Perm J. 2015;19(3):29–36.

Boers M, Idzerda L, Kirwan JR. Toward a generalized framework of core measurement areas in clinical trials: a position paper for OMERACT 11. J Rheumatology 2014;4 (5):978–985.

• Liem IS, Kammerlander C, Suhm N, Blauth M, Roth T, Gosch M, et al. Identifying a standard set of outcome parameters for the evaluation of orthogeriatric co-management for hip fractures. Injury. 2013;44:1402–12 Expert panelists identify and discuss the merits and validity of a critical set of measures, when available and feasible, to capture change in patients with hip fracture. The evaluation cuts across different professions including orthogeriatricians.

Dyer SM, Crotty M, Fairhall N, Magaziner J, Beaupre LA, Cameron ID, et al. A critical review of the long-term disability outcomes following hip fracture. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:158.

World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning disability and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

Health Quality Ontario. Quality Matters. Toronto, n.d. 30 December 2019. https://www.hqontario.ca/what-is-health-quality/quality-matters-a-plan-for-health-quality.

• Ganda K, Puech M, Chen JS, Speerin R, Bleasel J, Center JR, et al. Models of care for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24.2:393–406 A comprehensive review including a thorough classification of Fracture Liaison services.

• Wu CH, Kao IJ, Hung WC, Lin SC, Liu HC, Hsieh MH, et al. Economic impact and cost-effectiveness of fracture liaison services: a systematic review of the literature. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29.6:1227–42 The most recent and comprehensive systematic review of the economic aspects of Fracture Liaison Services currently available.

Sander B, Elliot-Gibson V, Beaton DE, Bogoch ER, Maetzel A. A coordinator program in post-fracture osteoporosis management improves outcomes and saves costs. J Bone Jt Surg. 2008;90(6):1197–205.

Majumdar SR, Lier DA, Beaupre LA, Hanley DA, Maksymowych WP, Juby AG, et al. Osteoporosis case manager for patients with hip fractures: results of a cost-effectiveness analysis conducted alongside a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169. 1:25.

Morrish DW, Beaupre LA, Bell NR, Cinats JG, Hanley DA, Harley CH, et al. Facilitated bone mineral density testing versus hospital-based case management to improve osteoporosis treatment for hip fracture patients: additional results from a randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(2):209–15.

Majumdar SR, Lier DA, FA MA, Rowe BH, Siminoski K, Hanley DA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of osteoporosis interventions for “incidental” vertebral fractures. Am J Med. 2013;126.2:169 e9–169 e17.

Majumdar SR, Lier D, Hanley DA, Juby AG, Beaupre LA. Economic evaluation of a population-based osteoporosis intervention for outpatients with non-traumatic non-hip fractures: the "Catch a Break" 1i [type c]. FLS. 2017;28.6:1965–77.

Cooper MS, Palmer AJ, Seibel MJ. Cost-effectiveness of the Concord Minimal Trauma Fracture Liaison service, a prospective, controlled fracture prevention study. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(1):97–107.

Osteoporosis Canada. Appendix C: best practices for post-fracture osteoporosis care; fracture liaison services. 2013.

Department of Health. Fracture prevention services: an economic evaluation. Leads; 2009. (https://clinicalinnovation.org.uk/resource/fracture-prevention-services-economic-evaluation/. Last accessed: March 29, 2020.)

McLellan AR, Wolowacz SE, Zimovetz EA, Beard SM, Lock S, McCrink L, et al. Fracture liaison services for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture: a cost-effectiveness evaluation based on data collected over 8 years of service provision. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22(7):2083–98.

International Osteoporosis Foundation. Health economics. Capture the Fracture, n.d. (https://www.capturethefracture.org/health-economics, last accessed March 29, 2020)

Leal J, Gray AM, Hawley S, Prieto-Alhambra D, Delmestri A, Arden NK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Orthogeriatric and fracture liaison service models of care for hip fracture patients: a population-based study: cost-effectiveness of fracture liaison service models. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(2):203–11.

Walters S, Khan T, Ong T, Sahota O. Fracture liaison services: improving outcomes for patients with osteoporosis. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:117–27.

Yong JHE, Masucci L, Hoch JS, Sujic R, Beaton D. Cost-effectiveness of a fracture liaison service -- a real world evaluation after 6 years of service provision. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(1):231–40.

Newman ED, Ayoub WT, Starkey RH, Diehl JM, Wood GC. Osteoporosis disease management in a rural health care population: hip fracture reduction and reduced costs in postmenopausal women after 5 years. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14(2):146–51.

National Hip Fracture Database Annual Report 2018. National hip fracture database annual report. 2010. https://www.nhfd.co.uk/20/hipfractureR.nsf/docs/2018Report. Last accessed March 29, 2020.

National Hip Fracture Database Annual Report. 2010. https://www.nhfd.co.uk/20/hipfractureR.nsf/945b5efcb3f9117580257ebb0069c820/7de8dac5ec3b468980257d4f005188f2/$FILE/NHFD2010Report.pdf. Last accessed March 29, 2020.

Griffiths, EJ, Stevenson D, Porteous, MJ. Cost savings of using a cemented total hip replacement. An analysis of the National Joint Registry data. 94-B. 8, 2012. Pp. 2013-5.

Pivec R, Johnson AJ, Mears SC. Hip Arthroplasty. Lancet. 2012;380(9855):1768–77.

Paxton EW, Inacio MCS, Kiley ML. The Kaiser Permanente implant registries: effect on patient safety, quality improvement, cost effectiveness, and research opportunities. Perm J. 2012;16(2):36–44.

Lindley R. Hip fracture: the case for a funded national registry. Lets implement what we know and avoid deaths from hip fracture. MJA. 2014;201(7):368–70.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Orthopedic Management of Fractures

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hoang-Kim, A., Kanengisser, D. Developing Registries and Effective Care Models for the Management of Hip Fractures: Aligning Political, Organizational Drivers with Clinical Outcomes. Curr Osteoporos Rep 18, 180–188 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-020-00582-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11914-020-00582-7