Abstract

Purpose of Review

There are three main components of peer-based approaches regardless of type: education, social support, and social norms. The purpose of this scoping review was to examine evidence in the literature among peer-based interventions and programs of components and behavioral mechanisms utilized to improve HIV care cascade outcomes.

Recent Findings

Of 522 articles found, 40 studies were included for data abstraction. The study outcomes represented the entire HIV care cascade from HIV testing to viral suppression. Most were patient navigator models and 8 of the studies included all three components. Social support was the most prevalent component. Role modeling of behaviors was less commonly described.

Summary

This review highlighted the peer behavioral mechanisms that operate in various types of peer approaches to improve HIV care and outcomes in numerous settings and among diverse populations. The peer-based approach is flexible and commonly used, particularly in resource-poor settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally, the prevalence of HIV is 37.7 million individuals, with the highest burden in sub-Sharan Africa [1]. Additionally, 1.5 million individuals are newly infected with HIV, and 680,000 individuals die of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related illnesses annually. As of 2020, 84% of individuals living with HIV knew of their HIV status, with 87% of those individuals accessing treatment, and 90% of those on treatment being virally suppressed. However, there is a need to improve the percentage of individuals who are aware of their HIV status and those living with HIV accessing treatment in order to reach the 90–90-90 goals [1]. Furthermore, a recent UNAIDS reports set 95–95-95 targets by 2025 to reduce the number of new HIV infection and those dying of AIDS-related illnesses [2]. To reach these goals, it is important to consider priority populations where disparities persist among the HIV care cascade, including inequalities in HIV prevention resources and treatment access. Specifically, sex workers and their clients, gay and other men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, and transgender persons account for 65% of HIV infections globally [2]. In the USA, additional disparities exist by sex and race: the lifetime risk of HIV infection was 1 in 76 for males and 1 in 309 for females. However, Black (1 in 27), Hispanic (1 in 50), and Native American (1 in 116) males, and Black (1 in 75) and Hispanic (1 in 287) women had elevated lifetime risks [3].

Peer-based approaches have demonstrated success in reaching stigmatized, vulnerable, and hard-to-access populations with behavioral and health interventions. While the definitions of “peer” varies, what is common across numerous published studies and reviews is that a peer is an individual that shares a characteristic with a target audience (e.g., demographics, cultural characteristics, health outcomes or diagnoses, or specific behaviors, such as injection practices). Persons living with HIV (PLWH) need to navigate a complicated health care system, with a myriad of HIV providers who can include medical doctors, nurses, case managers, counselors, social workers, and pharmacists, which can increase the barriers to care among patients who have had limited prior care, have low healthcare literacy, and/or have negative perspectives and mistrust of the healthcare system. Peer-based approaches can be an effective means of improving HIV care cascade outcomes for people at risk for HIV and PLWH.

Types of Peer Approaches

Peer-based approaches exist along a continuum that ranges from natural helpers to paraprofessionals [4]. The natural leader model is one in which peers are engaged in helping others within their personal social networks and/or community. The natural leader model [5] is based on the premise that individuals exist within personal social networks comprised of various individuals such as kin, friends, sex partners, or among whom a set of characteristics is shared [6]. Individuals within these networks are seen as familiar and credible and therefore can diffuse information and resources and influence behaviors of others in these networks. Related to the natural leader model is the popular opinion leader (POL) model, in which the peer is an individual who is nominated based upon their popularity within a social network. Their position in the network is based on centrality or betweenness that allows their influence to diffuse through the social network and therefore this individual has an ability to influence others. Accordingly, a POL can be trained to provide information and education to network members and to endorse health promoting behaviors and social norms [7,8,9]. In paraprofessional peer-based approaches, peers hold a more formalized role, often as a health educator or member of the medical team. Examples of paraprofessional peer-based approaches include the peer navigator and community health worker models, both of which assume that sharing lived experiences based on a characteristic (e.g., person living with HIV) enables the peer to establish trust and support [10,11,12]. In these models, the peer is often more formally hired and sometimes paid for their work.

Peer-based approaches are informed by numerous social influence theories, including social learning theory [13], social cognitive theory [13], and social comparison theory [14]. Social learning theory posits that individuals learn behaviors by watching others. Self-efficacy is an important component of the social cognitive theory and refers to a person’s confidence in their ability to perform a behavior, which increases with practice and feedback from others. Finally, social comparison theory posits that individuals compare themselves with different groups or social identities and align their behavior to match the reference group. This theory underscores the role of social norms in behavior change.

Components of Peer-Based Approaches and Associated Mechanisms of Action

There are three main components of peer-based approaches regardless of type: education, social support, and social norms (see Fig. 1) [15,16,17,18]. These components operate through peer-based behavioral mechanisms to impact health outcomes. The education component entails the peer providing information and instructions to the target audience to increase knowledge about risk, prevention, and treatment of a condition. Education often involves skills, building (e.g., strategies for medication adherence) and problem-solving skills. The social support component includes emotional (caring, empathy), instrumental (assisting in tangible needs such as transportation), and appraisal support (assisting in decision making and providing feedback) [19]. These different types of social support enable the peer to engage in a range of behaviors such as encouragement, offering suggestions and options, linkage and transportation to services, and appointment and medication reminders, among others [20,21,22]. Finally, peers can introduce or change social norms (the perceptions of others’ behaviors) to align with the health outcome goals of the program [23,24,25]. For example, by role modeling ART adherence or HIV testing behaviors, the peer can influence the individual’s self-efficacy to adopt this target behavior [26].

Many systematic reviews have been conducted in the last decade exploring the impact of peer-based interventions on HIV outcomes. One 2011 systematic review found that peer interventions for PLWH were efficacious in improving HIV care cascade outcomes but required further study and more rigorous study designs [27]. Genberg et al. [28] found mixed findings on the impact of peers on HIV care cascade outcomes and mortality [28]. A scoping review restricted to people with substance use disorders found that peer-based social network interventions improved retention in HIV care and ART adherence [26]. Berg et al. [29] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis showing modest but superior retention in HIV care, ART adherence, and viral load suppression among individuals engaged in peer support interventions [29]. Another systematic review showed improvements in the HIV care cascade among participants of peer and community-led programs [30]. Together, these studies show the potential for peer support interventions to improve outcomes along the HIV care cascade among diverse populations. However, no review to date has examined the behavioral mechanisms in peer support interventions or their role in impacting HIV care cascade outcomes.

Despite extensive literature on the efficacy and promise of peer-based approaches to impact HIV care outcomes, there remain several gaps in understanding specific component and behavioral mechanisms utilized or how these contribute to the outcomes of interest. For example, the topics of education and the types of support provided (e.g., instrumental, emotional) are often under-described. Another frequent gap in literature on this subject is a lack of detail about the characteristics of peers included in interventions, as well as the elements of their training and monitoring. Often, peers do not have specialized training in HIV clinical care or counseling yet are relied upon to provide a high level of support and information in HIV settings. It is therefore important to understand the types and duration of training these peers receive. Finally, many peer-specific HIV interventions do not include data on the impact of the approach on the peers’ own HIV prevention or adherence behavior. Without these details, replication and implementation of these interventions is hindered. The purpose of this scoping review was to examine evidence in the literature among peer-based interventions and programs of components and behavioral mechanisms utilized to improve HIV care cascade outcomes.

Methods

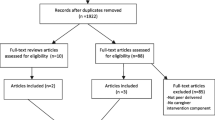

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the 2018 PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist [31].

Inclusion Criteria

This scoping review examined the theoretical and behavioral mechanisms of peer-based approaches to address HIV outcomes. Peers were defined as individuals who (1) shared at least one key characteristic with the target population (e.g., race, sex, sexual orientation, HIV status, drug use status); (2) engaged in communication with target participants to provide education; (3) provided emotional and informational and/or appraisal support, and (4) role modeled behaviors to achieve the HIV care cascade outcome of interest. Articles were only included if they measured one or more outcomes along the HIV care cascade, including (1) HIV testing or knowledge of HIV status; (2) linkage or retention in care; (3) ART prescription or adherence; or (4) viral load suppression [32]. Articles were excluded if (1) peers provided emotional support only — justified based on the importance of instrumental and appraisal support — or (2) an HIV care cascade outcome was not included or measured.

Search Strategy

Searches were conducted in PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO using a combination of MeSH terms or CINAHL/PsycINFO equivalent in January 2022 (Supplementary Material 1). Search terms were for three broad concepts: (1) peer support, (2) HIV, and (3) HIV care cascade outcomes, which included knowledge of HIV status, linkage to care, prescription of ART, and HIV viral load suppression. A filter was applied to limit the search to published articles from the last 5 years based on the parameters outlined by the Journal. Reference lists from studies that met inclusion criteria were also reviewed for additional relevant studies. All publications were exported to Endnote and duplicates removed.

Study Selection

Screening was conducted in two stages. Two reviewers independently screened all articles identified from the initial search in a two-stage process, which increased scrutiny of all records based on the inclusion criteria. First, two reviewers independently screened each title and abstract for relevance based on the inclusion criteria. Next, the same two reviewers independently reviewed each of the full texts for article inclusion in the data extraction phase. In both stages, any disagreements were adjudicated by a third reviewer. Throughout the process of screening titles/abstracts and full-texts, reviewers were not blinded to the authors, funding, or other information regarding publication.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers extracted data including details of peers, settings, target sample, measurement of outcomes, and main findings. Details of peers included the type of peer, type of peer program, identified theory, peer characteristics, role, skills and behaviors, and compensation. Finally, components of the peer-approach included (1) education; (2) social support: emotional, instrumental, and appraisal; and (3) social norms. We further coded approaches based on the behavioral mechanisms associated with the program components: (education) (a) knowledge, (b) skills building and problem-solving; (social support): (a) encouragement, (b) linkage, (c) transportation, (d) reminders; and (social norms) (a) role modeling.

Results

Figure 1 displays the PRISMA consort diagram. A total of 522 articles were found using the search terms in PubMed, CINAHL, and PsycINFO, and 156 of which were duplicates. AW and SP independently screened 366 title and abstracts for relevance, and 176 of which were irrelevant. AW and SP independently reviewed 172 full texts for inclusion, with KT adjudicating any disagreements. Forty studies were included in this scoping review, with KT and OH conducting data extraction.

Study Characteristics

Table 1 displays study characteristics. Most of the included studies were conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa (n = 24); there were n = 8 studies conducted in the USA, n = 3 in Central/South America, n = 3 in Southeast Asia, and n = 1 in Canada. The study outcomes represented the entire HIV care cascade from uptake of HIV testing to viral suppression (Table 1). Some articles included more than one outcome, such as linkage and viral load. Along the HIV care cascade, articles had a combination of the following outcomes: HIV testing (n = 7), linkage to care (n = 10), ART initiation and/or adherence (n = 5), retention to care (n = 7), engagement in care (n = 5), and viral load suppression (n = 8). Other outcomes included accessing auxiliary services, internalized stigma, acceptability and feasibility of the peer-approach, and partner involvement. Only one of the studies included addressed the impact that the peer role had on the peer’s own HIV care outcomes.

The target populations included general adult (n = 11), youth and adolescent PLWH (ages 12–18) (n = 8), including those who were newly diagnosed (n = 4), individuals initiating ART (n = 1), female sex workers (n = 5), sexual and gender minority men (n = 10), transgender women (n = 4), pregnant women (n = 2), and individuals with substance use disorder (n = 3).

Different terminologies were used to describe and refer to the peers. Within those following a navigator model, peers were labeled as either peer navigator, patient navigator, peer educator, peer counselor, peer mentor, health navigator, or community-led peer. In those engaging a POL model, peers were described as treatment ambassadors or peer educators. In the natural leader model, the peers were described as peer mentors and community health support workers.

Types of Models

The majority of peer-approaches engaged the patient navigator approach (n = 30). n = 8 were popular opinion leader [34, 36, 45, 47, 52, 56, 57, 62], and n = 3 were natural leader models [6, 37, 48]. In all studies except one, peers were selected based upon sharing the characteristic of HIV status. Some additionally matched peers on behavioral characteristics, such as female sex workers or individuals with a history of incarceration.

Most of the studies did not specify a theory used to inform the intervention or outline the training of the peers (n = 30). The information-motivation-behavior theory was used in five studies [6, 44, 45, 62, 70]. Other theories mentioned were the theory of gender and power (n = 1) [52], theory of gender affirmation (n = 1) [52], strengths-based philosophy (n = 1) [53], the unified theory of behavior (n = 1) [54], community-based participatory (n = 1) [34], social cognitive theory (n = 3) [38, 43, 59], and theory of triadic influence [47].

Training of the Peers

While most articles did not describe any information about the training of their peers, some included specific details. Examples of training descriptions included “in-person group workshops, informal role-playing, standardized role playing, and then recertification with standardized patients. Mentors were recertified with standard patients every 6 months” (page 679, Giordano [44]) and “44 training hours in HIV communication, anti-oppression harm reduction and self care” (Eaton [42]). Two studies explicitly mentioned that training included self-care strategies.

Compensation of the peers was mentioned in n = 17 of the studies, with varying details on the amounts and frequency (e.g., paid for every eligible participant recruited, hourly, specific amount of money per mention). In most of the studies, compensation was not mentioned at all.

Components and Mechanisms

As shown in Table 2, n = 8 of the studies included all three components (education, social support, and social norms [6, 38, 42,43,44, 47, 52, 62, 70]. Most studies included the education component, in which peers discussed or shared information (print and verbal) about various topics including HIV treatment knowledge, minimizing side effects, the importance of medication, HIV self-testing, adherence clubs, and other HIV care-related topics.

Social support was the most prevalent component. In addition to emotional support, peers provided instrumental support through linkage to clinicians and reminders about appointments and appraisal support through motivation to make decisions about keeping appointments and adherence. Role modeling of behaviors was less commonly described. When included, role modeling entailed demonstrating how to successfully manage HIV infection and HIV self-testing. Other examples included peers sharing personal stories related to their HIV diagnosis, challenges with addiction, personal barriers to care, successful adherence, disclosure, and overcoming substance use or incarceration.

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to examine diverse peer-based intervention models to identify the peer components and behavioral mechanisms engaged to improve HIV care outcomes among participants. We found that only one-third of the studies described use of all three components (education, social support, and social norms) and associated behavioral mechanisms (knowledge and skills development, problem-solving, linkage and assistance with daily HIV care-related tasks, and role modeling of the skills). These findings expand upon current synthesis of literature, which has summarized the efficacy and effectiveness of peer-based HIV interventions [26,27,28,29,30], by focusing on the peer-behavioral mechanisms of action.

Providing social support was the most common component included in these interventions. There is a wealth of evidence that social support is associated with positive health outcomes. Indeed, social support is a necessary but insufficient approach to changing behaviors. We excluded studies in which the peer’s role was only to provide emotional support for this reason. Training peers in skills for linkage and assessing needs for transportation or other assistance and assisting with decision making enables the individual to identify and overcome barriers to care.

The least mentioned component identified in these interventions was peers introducing or changing social norms through role modeling and building individual’s self-efficacy to adopt the behavior of interest. Social learning theory and social cognitive theory emphasize the importance of role modeling behaviors to increase self-efficacy to help individuals sustain behavior changes. The premise of many studies was that sharing characteristics and familiarity of the community and context was a proxy for role modeling. This assumption may be one possible reason for the mixed results on the effectiveness of peer-based approaches and underscores the need for programs to explicitly train peers to demonstrate and provide feedback about behavior. One recommendation for the field is to document the extent to which the peers in the programs describing how frequently they role model or demonstrate behaviors and which behaviors/skills are the most commonly role modeled. This will inform the evaluation of the program and identify gaps in training of the peers.

Little detail was provided on the content or dose of peer communication with intervention participants: for example, whether conversations were typically about adherence or HIV care appointments or other non-HIV-related issues such as income, housing, childcare, or relationship matters were not specified. Programs should prepare peers to be able to discuss resources that may not be specific to HIV but could be important barriers to care engagement, such as food programs or childcare services. Furthermore, documenting examples of different questions and conversations that reflect the context where the study was conducted can inform evaluation of the components of the peer program and be used as future training materials.

There was heterogeneity in the descriptions of the training of peers. This may be in part due to more detailed explanations in protocol papers that were excluded from this review. Replication and dissemination of successful programs relies on details about the training content and length of time in which peers are trained to participate in interventions.

Very few studies included self-care as a training activity for the peers. However, several of the studies did include check-in training sessions to assess and boost peers’ skills. As the peers are PLWH themselves and often shared other marginalized identities with target participants, self-care behaviors are important to reduce burnout and improve retention of the peers. Self-care can be structured as an activity to be conducted during supervision or on-going training activities. Self-care can also be role-modeled by the peers to other PLWH.

One of the promising aspects of peer approaches is its potential to offer a pathway for employment. Several studies did formally hire their peers, and others provided peers with monthly stipends. Economic insecurity is well established as a determinant of adverse HIV care outcomes, while employment can have a positive impact on PLWH peers [72]. Future peer-based interventions should seek to provide formalized employment opportunities and compensation to peers in order to promote positive outcomes among the peer participants. Additionally, it remains important to have continued training and monitoring of peers and other intervention-related staff by qualified supervisors. Lack of understanding about the peer role at clinical sites was cited as a common challenge and can lead to competition between staff, low trust, and misunderstandings about the role of peers [73, 74]. Recommendations for promoting peer-based programs and integration in the HIV healthcare workforce include establishing an infrastructure for training, education, and certification, as well as defining the professional identity of peers though core competencies and a common scope of practice as well as opportunities for advancement. There may be some peers who prove to be particularly effective in their roles, yet without systems in place to document the various elements of these programs, successes cannot be replicated. Furthermore, sustainable financing mechanisms to support successful integration of peers into a multi-disciplinary team should be established where feasible. When payment is not possible, systems that emphasize the intrinsic and extrinsic rewards of peers can be accomplished through acknowledgements or certificates of appreciation.

Limitations

A major limitation of this study was the often-limited availability of information in published literature regarding peer-based interventions. Articles were excluded if they did not discuss the components of their peer-based intervention or reviewers could not determine whether peers provided more than emotional support. There was heterogeneity in how studies reported peer-based interventions. This variability reduced the ability to properly assess the peer components and behavioral mechanisms, and to a larger extent, limited others in reproducing peer-based interventions which successfully improved HIV outcomes. Additionally, the review was limited to literature published in the last 5 years to synthesize the mechanisms from the latest interventions that impact HIV care cascade outcomes, as they address the latest priority areas which peers could address. This substantially limited the number of interventions included. Despite these limitations, we identified forty studies for inclusion and extraction of peer components and behavioral mechanisms.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlighted many of the peer behavioral mechanisms that operate in various types of peer approaches to improve HIV care and outcomes in numerous settings and among diverse populations. The peer-based approach is flexible and commonly used, particularly in resource-poor settings due to its low cost. Future studies should include more explicit details about the components and mechanisms that were used within peer-based interventions and explicitly evaluate the dose and impact on individual and peer health outcomes including changes in stigma. Additionally, future research should evaluate the inclusion/exclusion of specific mechanisms in the context of the interventions’ efficacy.

References

UNAIDS.org. UNAIDS Data 2021 [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2022.

UNAIDS.org. Ending inequalities and getting on track to end AIDS by 2030: a summary of the commitments and targets within the United Nations General Assembly’s 2021 Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2021-political-declaration_summary-10-targets_en.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2022.

Singh S, Xiaohong H, Hess K. Estimating the lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://ww2.aievolution.com/cro2201/index.cfm?do=abs.viewAbs&abs=1154. Accessed 15 Feb 2022.

Eng E, Parker E, Harlan C. Lay health advisor intervention strategies: a continuum from natural helping to paraprofessional helping. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(4):413–7.

Tobin KE, Kuramoto SJ, Davey-Rothwell MA, Latkin CA. The STEP into action study: a peer-based, personal risk network-focused HIV prevention intervention with injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addiction. 2011;106(2):366–75.

Tobin K, Edwards C, Flath N, Lee A, Tormohlen K, Gaydos CA. Acceptability and feasibility of a peer mentor program to train young Black men who have sex with men to promote HIV and STI home-testing to their social network members. AIDS Care. 2018;30(7):896–902.

HIV risk behavior reduction following intervention with key opinion leaders of population: an experimental analysis. | AJPH | Vol. 81 Issue 2 [Internet]. Available from: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/ajph.81.2.168. Accessed 15 Feb 2022.

Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Kalichman SC, Diaz YE, et al. Community AIDS/HIV risk reduction: the effects of endorsements by popular people in three cities. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(11):1483–9.

Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Sikkema KJ, McAuliffe TL, Roffman RA, Solomon LJ, et al. Randomised, controlled, community-level HIV-prevention intervention for sexual-risk behaviour among homosexual men in US cities. Community HIV Prevention Research Collaborative. Lancet. 1997;350(9090):1500–5.

Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, Nieman CL, Joo JH, Lin FR, Gitlin LN, Han HR. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):e3-28.

Latkin C, Friedman S. Drug use research: drug users as subjects or agents of change. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47(5):598–9.

Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Skeer MR, Driskell J, Goshe BM, Covahey C, et al. Demonstration and evaluation of a peer-delivered, individually-tailored, HIV prevention intervention for HIV-infected MSM in their primary care setting. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(5):949–58.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

Dijikstra P, Gibbons FX, Buunk AP. Social comparison theory. In: Maddux JE, Tangney JP, editors. Social psychological foundations of clinical psychology. The Guilford Press; 2010. p. 195–211.

Kahan S, Gielen AC, Fagan PJ, Green LW, editors. Health behavior change in populations. JHU Press; 2014.

Sokol R, Fisher E. Peer support for the hardly reached: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(7):e1-8.

Petosa RL, Smith LH. Peer mentoring for health behavior change: a systematic review. Am J Health Educ. 2014;45(6):351–7.

Simoni JM, Franks JC, Lehavot K, Yard SS. Peer interventions to promote health: conceptual considerations. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(3):351–9.

Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM. Social Epidemiology. Oxford University Press; 2014. 641 p.

Nelson E, Faustin Z, Stern J, Kasozi J, Klabbers R, Masereka S, Tsai AC, Bassett IV, O’Laughlin KN. Social support and linkage to HIV care following routine HIV testing in a Ugandan refugee settlement. AIDS Behav. 2022;17:1–8.

Painter TM, Song EY, Mullins MM, Mann-Jackson L, Alonzo J, Reboussin BA, et al. Social support and other factors associated with HIV testing by Hispanic/Latino gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the U.S. South. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(3):251–65.

Chandran A, Benning L, Musci RJ, Wilson TE, Milam J, Adedimeji A, et al. The longitudinal association between social support on HIV medication adherence and healthcare utilization in the women’s interagency HIV study. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(8):2014–24.

White JJ, Yang C, Tobin KE, Beyrer C, Latkin CA. Individual and social network factors associated with high self-efficacy of communicating about men’s health issues with peers among Black MSM in an urban setting. J Urban Health. 2020;97(5):668–78.

Fleming PJ, DiClemente RJ, Barrington C. Masculinity and HIV: dimensions of masculine norms that contribute to men’s HIV-related sexual behaviors. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(4):788–98.

Young SD, Cumberland WG, Nianogo R, Menacho LA, Galea JT, Coates T. The HOPE social media intervention for global HIV prevention in Peru: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(1):e27-32.

Ghosh D, Krishnan A, Gibson B, Brown SE, Latkin CA, Altice FL. Social network strategies to address HIV prevention and treatment continuum of care among at-risk and HIV-infected substance users: a systematic scoping review. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(4):1183–207.

Simoni JM, Nelson KM, Franks JC, Yard SS, Lehavot K. Are peer interventions for HIV efficacious? A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1589–95.

Genberg BL, Shangani S, Sabatino K, Rachlis B, Wachira J, Braitstein P, et al. Improving engagement in the HIV care cascade: a systematic review of interventions involving people living with HIV/AIDS as peers. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(10):2452–63.

Berg RC, Page S, Øgård-Repål A. The effectiveness of peer-support for people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6): e0252623.

Ayala G, Sprague L, van der Merwe LLA, Thomas RM, Chang J, Arreola S, et al. Peer- and community-led responses to HIV: a scoping review. PLoS One. 2021;16(12): e0260555.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Webel AR, Okonsky J, Trompeta J, Holzemer WL. A systematic review of the effectiveness of peer-based interventions on health-related behaviors in adults. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):247–53.

Abubakari GM, Turner D, Ni Z, Conserve DF, Dada D, Otchere A, Amanfoh Y, Boakye F, Torpey K, Nelson LE. Community-based interventions as opportunities to increase HIV self-testing and linkage to care among men who have sex with men–lessons from Ghana, West Africa. Front Public Health. 2021;11(9):581.

Audet CM, Blevins M, Chire YM, Aliyu MH, Vaz LME, Antonio E, et al. Engagement of men in antenatal care services: increased HIV testing and treatment uptake in a community participatory action program in Mozambique. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(9):2090–100.

Aung S, Hardy N, Chrysanthopoulou S, Htun N, Kyaw A, Tun MS et al. Evaluation of peer-to-peer HIV counseling in Myanmar: a measure of knowledge, adherence, and barriers. AIDS Care. 2021; 1–9.

Cabral HJ, Davis-Plourde K, Sarango M, Fox J, Palmisano J, Rajabiun S. Peer support and the HIV continuum of care: results from a multi-site randomized clinical trial in three urban clinics in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(8):2627–39.

Chanda MM, Ortblad KF, Mwale M, Chongo S, Kanchele C, Kamungoma N, et al. HIV self-testing among female sex workers in Zambia: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11): e1002442.

Cunningham WE, Weiss RE, Nakazono T, Malek MA, Shoptaw SJ, Ettner SL, Harawa NT. Effectiveness of a peer navigation intervention to sustain viral suppression among HIV-positive men and transgender women released from jail: the LINK LA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(4):542–53.

Cuong DD, Sönnerborg A, Van Tam V, El-Khatib Z, Santacatterina M, Marrone G, Chuc NT, Diwan V, Thorson A, Le NK, An PN. Impact of peer support on virologic failure in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy-a cluster randomized controlled trial in Vietnam. BMC infect dis. 2016;16(1):1–4.

Davis DA, Aguilar JM, Arandi CG, Northbrook S, Loya-Montiel MI, Morales-Miranda S, Barrington C. “Oh, I’m Not Alone”: experiences of HIV-positive men who have sex with men in a health navigation program to promote timely linkage to care in Guatemala City. AIDS Educ Prev. 2017;29(6):554–66.

Denison JA, Burke VM, Miti S, Nonyane BAS, Frimpong C, Merrill KG, et al. Project YES! Youth Engaging for Success: a randomized controlled trial assessing the impact of a clinic-based peer mentoring program on viral suppression, adherence and internalized stigma among HIV-positive youth (15–24 years) in Ndola, Zambia. PLoS One. 2020;15(4): e0230703.

Eaton AD, Carusone SC, Craig SL, Telegdi E, McCullagh JW, McClure D, et al. The ART of conversation: feasibility and acceptability of a pilot peer intervention to help transition complex HIV-positive people from hospital to community. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3): e026674.

Enriquez M, Cheng AL, McKinsey D, Farnan R, Ortego G, Hayes D, Miles L, Reese M, Downes A, Enriquez A, Akright J. Peers keep it real: re-engaging adults in HIV care. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2019;4(18):2325958219838858.

Giordano TP, Cully J, Amico KR, Davila JA, Kallen MA, Hartman C, Wear J, Buscher A, Stanley M. A randomized trial to test a peer mentor intervention to improve outcomes in persons hospitalized with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):678–86.

Graham SM, Micheni M, Chirro O, Nzioka J, Secor AM, Mugo PM, Kombo B, van Der Elst EM, Operario D, Amico KR, Sanders EJ. A randomized controlled trial of the Shikamana intervention to promote antiretroviral therapy adherence among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Kenya: feasibility, acceptability, safety and initial effect size. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(7):2206–19.

Hacking D, Mgengwana-Mbakaza Z, Cassidy T, Runeyi P, Duran LT, Mathys RH, Boulle A. Peer mentorship via mobile phones for newly diagnosed HIV-positive youths in clinic care in Khayelitsha, South Africa: mixed methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(12): e14012.

Katz IT, Bogart LM, Fitzmaurice GM, Staggs VS, Gwadz MV, Bassett IV, Cross A, Courtney I, Tsolekile L, Panda R, Steck S. The treatment ambassador program: a highly acceptable and feasible community-based peer intervention for South Africans living with HIV who delay or discontinue antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(4):1129–43.

Lifson AR, Workneh S, Hailemichael A, Demisse W, Slater L, Shenie T. Implementation of a peer HIV community support worker program in rural Ethiopia to promote retention in care. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2017;16(1):75–80.

MacKellar D, Williams D, Dlamini M, Byrd J, Dube L, Mndzebele P, et al. Overcoming barriers to HIV care: findings from a peer-delivered, community-based, linkage case management program (CommLink), Eswatini, 2015–2018. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(5):1518–31.

MacKellar D, Maruyama H, Rwabiyago OE, Steiner C, Cham H, Msumi O, Weber R, Kundi G, Suraratdecha C, Mengistu T, Byrd J. Implementing the package of CDC and WHO recommended linkage services: methods, outcomes, and costs of the Bukoba Tanzania combination prevention evaluation peer-delivered, linkage case management program, 2014–2017. PLoS One. 2018;13(12): e0208919.

MacKellar D, Williams D, Bhembe B, Dlamini M, Byrd J, Dube L, et al. Peer-delivered linkage case management and same-day ART initiation for men and young persons with HIV infection — Eswatini, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(23):663–7.

Maiorana A, Kegeles S, Salazar X, Konda K, Silva-Santisteban A, Cáceres C. ‘Proyecto Orgullo’, an HIV prevention, empowerment and community mobilisation intervention for gay men and transgender women in Callao/Lima, Peru. Glob Public Health. 2016;11(7–8):1076-92.40.

Myers JJ, Kang Dufour MS, Koester KA, Morewitz M, Packard R, Monico Klein K, Estes M, Williams B, Riker A, Tulsky J. The effect of patient navigation on the likelihood of engagement in clinical care for HIV-infected individuals leaving jail. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):385–92.

Ndhlovu CE, Kouamou V, Nyamayaro P, Dougherty L, Willis N, Ojikutu BO, Makadzange AT. The transient effect of a peer support intervention to improve adherence among adolescents and young adults failing antiretroviral therapy in Harare, Zimbabwe: a randomized control trial. AIDS Res Ther. 2021;18(1):1–1.

Nguyen VTT, Phan HT, Kato M, Nguyen QT, Le Ai KA, Vo SH, et al. Community-led HIV testing services including HIV self-testing and assisted partner notification services in Vietnam: lessons from a pilot study in a concentrated epidemic setting. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(S3): e25301.

Okoboi S, Lazarus O, Castelnuovo B, Nanfuka M, Kambugu A, Mujugira A, et al. Peer distribution of HIV self-test kits to men who have sex with men to identify undiagnosed HIV infection in Uganda: a pilot study. PLoS One. 2020;15(1): e0227741.

Ortblad K, Musoke DK, Ngabirano T, Nakitende A, Magoola J, Kayiira P, et al. Direct provision versus facility collection of HIV self-tests among female sex workers in Uganda: a cluster-randomized controlled health systems trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11): e1002458.

Phiri S, Tweya H, van Lettow M, Rosenberg NE, Trapence C, Kapito-Tembo A, et al. Impact of facility- and community-based peer support models on maternal uptake and retention in Malawi’s option B+ HIV prevention of mother-to-child transmission program: a 3-arm cluster randomized controlled trial (PURE Malawi). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;1(75):S140.

Reback CJ, Kisler KA, Fletcher JB. A novel adaptation of peer health navigation and contingency management for advancement along the HIV care continuum among transgender women of color. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(1):40–51.

Rocha-Jiménez T, Pitpitan EV, Cazares R, Smith LR. “He is the Same as Me”: key populations’ acceptability and experience of a community-based peer navigator intervention to support engagement in HIV care in Tijuana, Mexico. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2021;35(11):449–56.

Sam-Agudu NA, Ramadhani HO, Isah C, Anaba U, Erekaha S, Fan-Osuala C, et al. The impact of structured mentor mother programs on 6-month postpartum retention and viral suppression among HIV-positive women in rural Nigeria: a prospective paired cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;1(75):S173.

Senn TE, Braksmajer A, Coury-Doniger P, Urban MA, Rossi A, Carey MP. Development and preliminary pilot testing of a peer support text messaging intervention for HIV-infected Black men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(Suppl 2):S121–7.

Shah P, Kibel M, Ayuku D, Lobun R, Ayieko J, Keter A, Kamanda A, Makori D, Khaemba C, Ngeresa A, Embleton L. A pilot study of “peer navigators” to promote uptake of HIV testing, care and treatment among street-connected children and youth in Eldoret, Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(4):908–19.

Shahmanesh M, Mthiyane TN, Herbsst C, Neuman M, Adeagbo O, Mee P, et al. Effect of peer-distributed HIV self-test kits on demand for biomedical HIV prevention in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a three-armed cluster-randomised trial comparing social networks versus direct delivery. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(Suppl 4): e004574.

Steward WT, Sumitani J, Moran ME, Ratlhagana MJ, Morris JL, Isidoro L, Gilvydis JM, Tumbo J, Grignon J, Barnhart S, Lippman SA. Engaging HIV-positive clients in care: acceptability and mechanisms of action of a peer navigation program in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2018;30(3):330–7.

Steward WT, Agnew E, de Kadt J, Ratlhagana MJ, Sumitani J, Gilmore HJ, Grignon J, Shade SB, Tumbo J, Barnhart S, Lippman SA. Impact of SMS and peer navigation on retention in HIV care among adults in South Africa: results of a three-arm cluster randomized controlled trial. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(8): e25774.

Taiwo BO, Kuti KM, Kuhns LM, Omigbodun O, Awolude O, Adetunji A, et al. Effect of text messaging plus peer navigation on viral suppression among youth with HIV in the iCARE Nigeria pilot study. J Acquir Immune Def Syndr. 2021;87(4):1086–92.

Tapera T, Willis N, Madzeke K, Napei T, Mawodzeke M, Chamoko S, Mutsinze A, Zvirawa T, Dupwa B, Mangombe A, Chimwaza A. Effects of a peer-led intervention on HIV care continuum outcomes among contacts of children, adolescents, and young adults living with HIV in Zimbabwe. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2019;7(4):575–84.

Vu L, Burnett-Zieman B, Banura C, Okal J, Elang M, Ampwera R, et al. Increasing uptake of HIV, sexually transmitted infection, and family planning services, and reducing HIV-related risk behaviors among youth living with HIV in Uganda. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(2, Supplement 2):S22-8.

Westergaard RP, Genz A, Panico K, Surkan PJ, Keruly J, Hutton HE, et al. Acceptability of a mobile health intervention to enhance HIV care coordination for patients with substance use disorders. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2017;12(1):11.

Young B, Rosenthal A, Escarfuller S, Shah S, Carrasquillo O, Kenya S. Beyond the barefoot doctors: using community health workers to translate HIV research to service. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(10):2879–88.

Maulsby CH, Ratnayake A, Hesson D, Mugavero MJ, Latkin CA. A scoping review of employment and HIV. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(10):2942–55.

Waitzkin H, Getrich C, Heying S, Rodríguez L, Parmar A, Willging C, Yager J, Santos R. Promotoras as mental health practitioners in primary care: a multi-method study of an intervention to address contextual sources of depression. J Community Health. 2011;36(2):316–31.

Gutierrez Kapheim M, Campbell J. Best practice guidelines for implementing and evaluating community health worker programs in health care settings. [Internet]. Chicago: Sinai Urban Health Institute; 2014. Available from: https://chwcentral.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/CHW-BPG-for-CHW-programs-in-health-care-settings.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2022.

Funding

Abigail Winiker is supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Development Interdisciplinary Training in Trauma and Violence (T32 HD094687). Omeid Heidari is supported by the National Institute of Health Drug Epidemiology Training Grant (T32DA007292). Karin Tobin is supported by the National Institute of Health – Mental Health R34MH118178.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Karin E. Tobin, Omeid Heidari, Abigail Winiker, Sarah Pollack, Melissa Davey-Rothwell, Kamila Alexander, Jill Owczarzak, and Carl Latkin declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal studies performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Behavioral-Bio-Medical Interface

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(14.3 KB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tobin, K.E., Heidari, O., Winiker, A. et al. Peer Approaches to Improve HIV Care Cascade Outcomes: a Scoping Review Focused on Peer Behavioral Mechanisms. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 19, 251–264 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-022-00611-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-022-00611-3